Abstract

Approximately one‐third of patients diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma presenting with Stage IV disease do not survive past 5 years. We present updated efficacy and safety analyses in high‐risk patient subgroups, defined by Stage IV disease or International Prognostic Score (IPS) of 4–7, enrolled in the ECHELON‐1 study that compared brentuximab vedotin plus doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (A + AVD) versus doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) as first‐line therapy after a median follow‐up of 37.1 months. Among patients treated with A + AVD (n = 664) or ABVD (n = 670), 64% had Stage IV disease and 26% had an IPS of 4–7. Patients with Stage IV disease treated with A + AVD showed consistent improvements in PFS at 3 years as assessed by investigator (hazard ratio [HR], 0.723; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.537–0.973; p = 0.032). Similar improvements were seen in the subgroup of patients with IPS of 4–7 (HR, 0.588; 95% CI, 0.386–0.894; p = 0.012). The most common adverse events (AEs) in A + AVD‐treated versus ABVD‐treated patients with Stage IV disease were peripheral neuropathy (67% vs. 40%) and neutropenia (71% vs. 55%); in patients with IPS of 4–7, the most common AEs were peripheral neuropathy (69% vs. 45%), neutropenia (66% vs. 55%), and febrile neutropenia (23% vs. 9%), respectively. Patients in high‐risk subgroups did not experience greater AE incidence or severity than patients in the total population. This updated analysis of ECHELON‐1 shows a favorable benefit‐risk balance in high‐risk patients.

Keywords: brentuximab vedotin, ECHELON‐1, high risk Hodgkin lymphoma

1. INTRODUCTION

Despite advances in recent years, advanced‐stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) treated with doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) relapses or becomes refractory in 25%–30% of patients.1, 2, 3 Bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone (BEACOPPesc) results in higher initial disease control in younger, fit patients but at the expense of significantly higher acute and late toxicity, secondary malignancies, and treatment‐related mortality.4, 5, 6 Patients with Stage IV disease have a relatively poor prognosis, with an overall survival (OS) rate of approximately 76% at 5 years. 7 The development of more‐effective yet tolerable treatment options for patients with advanced‐stage cHL, especially those with high‐risk characteristics, is warranted.

Brentuximab vedotin (BV) is a novel antibody‐drug conjugate targeting the CD30 antigen expressed on Hodgkin Reed–Sternberg cells. Across a range of trials, BV has been shown to induce durable remissions in patients with cHL who relapsed after autologous stem cell transplant. In the pivotal trial, BV treatment resulted in a complete response (CR) rate of 34% (95% confidence interval [CI], 25.2–44.4) and objective response rate of 75% (95% CI, 64.9–82.6) per independent review committee. 8 Notably, a subset of 15 patients from this study achieved complete remission and maintained their response for ≥5 years; of these, six patients received consolidative allogeneic stem cell transplant, and nine patients received no further therapy after completing BV treatment. 9 The use of BV as a consolidation treatment option for adult patients with cHL at high risk of relapse or progression following autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant resulted in improved progression‐free survival (PFS) compared with placebo. 10 In a Phase 1 dose‐escalation study of BV in combination with AVD, 24 of 25 patients (96%) with newly diagnosed cHL achieved complete remission. 11 Based on these findings, a global, multicenter, open‐label, randomized, phase 3 clinical study, the ECHELON‐1 trial, was conducted to assess the efficacy and safety of a therapeutic combination of BV plus AVD (A + AVD) versus ABVD as first‐line therapy in advanced stage (III and IV) cHL. 12

At a median follow‐up of 24.6 months, primary analyses of ECHELON‐1 showed a 23% risk reduction for modified PFS (hazard ratio [HR] for progression, death, or modified progression event, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.60–0.98; p = 0.035) in patients receiving A + AVD, with 2‐year modified PFS rates of 82.1% (95% CI, 78.8%–85.0%) in patients receiving A + AVD and 77.2% (95% CI, 73.7%–80.4%) in those receiving ABVD. 12 At the primary analysis, 28 deaths had occurred with A + AVD and 39 with ABVD (HR for interim OS, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.44–1.17; p = 0.19). 12

This post hoc analysis includes the updated 3‐year efficacy and safety of A + AVD compared with ABVD (data cutoff, 15 October 2018; median follow‐up for PFS was 37.1 months) in a prespecified high‐risk patient subgroup presenting at baseline with Stage IV disease or an International Prognostic Score (IPS) of 4–7.

2. METHODS

2.1. Patient eligibility and study design

Full details of the ECHELON‐1 study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01712490; EudraCT 2011‐005450‐60) have been published.12, 13 Briefly, we recruited patients aged ≥18 years with histologically confirmed cHL (Ann Arbor stage III or IV) who had not been previously treated with systemic chemotherapy or radiotherapy and had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–2 (Figure S1).

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive A + AVD or ABVD intravenously on Days 1 and 15 of each 28‐day cycle for up to six cycles, with stratification by IPS (0–1, 2–3, or 4–7) and region (Americas, Asia, or Europe).

ECHELON‐1 was conducted in accordance with regulatory requirements; the protocol was approved by the institutional review boards and ethics committees at each registered site. Written informed consent per the local ethics committee was mandatory before enrollment. This study was conducted according to the guideline of the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice.

2.2. Endpoints

The primary endpoint was modified PFS per an independent review facility (IRF), defined as the time to disease progression, death, or modified progression event (with the latter defined as evidence of non‐CR after completion of frontline therapy according to review by an independent committee, followed by subsequent anticancer therapy). 12 Non‐CR was defined by an end‐of‐therapy positron emission tomography (PET) scan with a Deauville five‐point scale score of 3–5. The key secondary endpoint was OS (time from date of randomization to date of death). These endpoints were specified in the primary analysis (data cutoff, 20 April 2017).

PFS per investigator for the intent‐to‐treat (ITT) population was a preplanned supportive analysis. At a median follow‐up of 37.1 months, we report extended follow‐up of PFS (defined as time to progression or death) per the investigator for patients with Stage IV disease or an IPS of 4–7. Following the primary analysis, the protocol did not require investigators to submit further information to the IRF.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Stratified log‐rank testing was used to compare modified PFS and OS between the two treatment arms as part of the primary analysis and key secondary analysis in the ITT population. Stratification factors included geographic region and IPS at baseline. HRs, along with 95% CIs, were estimated using a stratified Cox model, with treatment as the explanatory variable.

In the primary analysis, a broad number of prespecified subgroup analyses was performed, including region, extranodal site involvement, IPS, sex, disease stage, and age. 12 The present subgroup analyses for PFS used unstratified Cox models and unstratified log‐rank testing and included the following subgroups: stage (III vs. IV) and IPS (0–1 vs. 2–3 vs. 4–7).

Extended follow‐up of modified PFS per IRF was not feasible following the primary analysis because the protocol did not require investigators to submit further information to the IRF. Additional supportive analyses were performed to evaluate the treatment effects on PFS per the investigator and OS in these two prespecified groups. An unstratified Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate HRs. All p values from subgroup analyses were based on unstratified log‐rank tests and are for descriptive purposes only, without multiplicity adjustment.

Safety was summarized for type, incidence, severity, seriousness, and relatedness of adverse events (AEs), as well as type, incidence, and severity of laboratory abnormalities. AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 10.1 or higher. Laboratory values were graded in accordance with the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 or higher (SAS Institute).

3. RESULTS

A total of 1334 patients (ITT population) at 218 sites in 21 countries were randomly assigned to receive A + AVD (n = 664) or ABVD (n = 670). The data cutoff date for the present updated analysis was 15 October 2018, with a median follow‐up of 37.1 months and primary data from 20 April 2017 at a median follow‐up of 24.6 months. Overall, 64% of patients had Stage IV disease (64% in the A + AVD arm; 63% in the ABVD arm); 26% had an IPS of 4–7 (25% in the A + AVD arm; 27% in the ABVD arm). Baseline characteristics were balanced between the two treatment arms and are presented in Table 1 for patients with Stage IV disease (n = 846) and in Table S1 for those with an IPS of 4–7 (n = 347).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with Stage IV disease at baseline

| Characteristic | A + AVD (n = 425) | ABVD (n = 421) |

|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 243 (57) | 243 (58) |

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 36 | 38 |

| IQR | 26.0–50.0 | 27.0–53.0 |

| Age category, n (%) | ||

| <45 years | 292 (69) | 260 (62) |

| 45–59 years | 82 (19) | 94 (22) |

| ≥60 years | 51 (12) | 67 (16) |

| IPS risk factors, n (%) | ||

| 0–1 | 55 (13) | 43 (10) |

| 2–3 | 225 (53) | 227 (54) |

| 4–7 | 145 (34) | 151 (36) |

| Bone marrow involvement at diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 142 (33) | 140 (33) |

| No | 271 (64) | 276 (66) |

| Unknown | 12 (3) | 5 (1) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 221 (52) | 217 (52) |

| 1 | 184 (43) | 181 (43) |

| 2 | 20 (5) | 22 (5) |

| Patients with any B symptom, n (%) | 276 (65) | 256 (61) |

Abbreviations: A + AVD, brentuximab vedotin plus doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IPS, International Prognostic Score , .

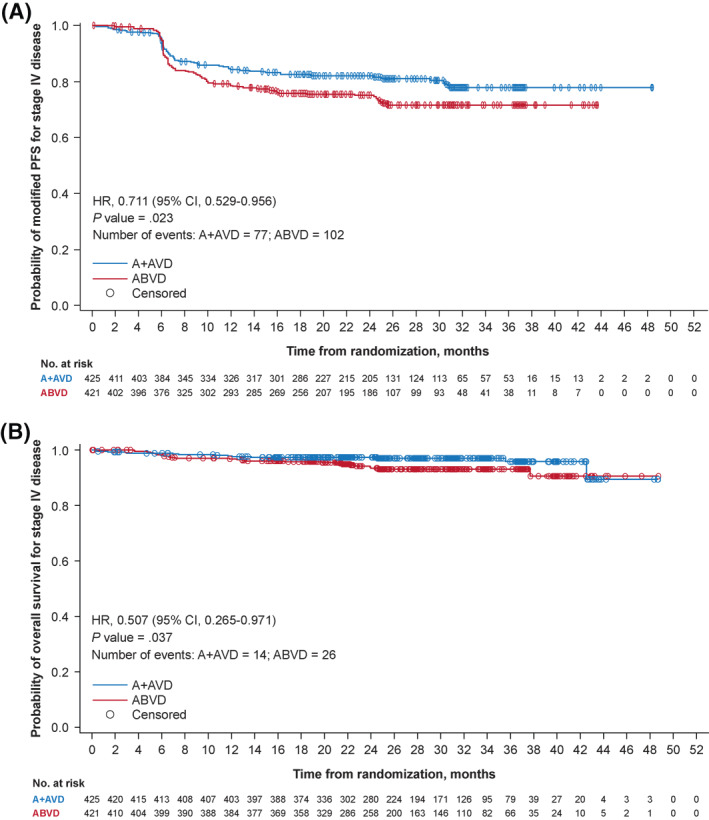

In patients with Stage IV disease at the time of the primary analysis, there was a 28.9% reduction in the risk of a modified PFS per IRF event in the A + AVD arm compared with the ABVD arm (HR, 0.711; 95% CI, 0.529–0.956; p = 0.023). The modified PFS rate per IRF at 2 years was 82.0% (95% CI, 77.8%–85.5%) in the A + AVD arm compared with 75.3% (95% CI, 70.6%–79.3%) in the ABVD arm (Figure 1A ). An interim analysis of OS indicated that patients with Stage IV disease who received A + AVD had an almost 50% reduction in the risk of death (14/425 [3.3%]) compared with those who received ABVD (26/421 [6.2%]), with an HR of 0.507 (95% CI, 0.265–0.971; p = 0.037); the estimated 2‐year OS rate was 97.4% (95% CI, 95.3%–98.5%) in the A + AVD arm and 93.4% (95% CI, 90.3%–95.6%) in the ABVD arm (Figure 1B). In patients with an IPS of 4–7, a 44.2% reduction was observed in the risk of a modified PFS per IRF event in the A + AVD arm compared with the ABVD arm (HR, 0.558; 95% CI, 0.357–0.874; p = 0.010). The modified PFS per IRF rate at 2 years was 77.0% (95% CI, 69.5%–82.9%) in the A + AVD arm compared with 69.2% (95% CI, 61.5%–75.8%) in the ABVD arm (Figure 2A). Among patients with an IPS of 4–7, the interim analysis of OS showed a 48.1% reduction in risk of death in patients who received A + AVD (11/169 [6.5%]) compared with those who received ABVD (22/178 [12.4%]), with an HR of 0.519 (95% CI, 0.252–1.070; p = 0.070; Figure 2B).

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of (A) modified PFS per the IRF and (B) OS by treatment arm among patients with Stage IV disease at primary analysis (data cutoff, 20 April 2017). Hazard ratios, 95% CIs, and p values from log‐rank tests are presented; circles indicate censored data. A + AVD, brentuximab vedotin plus doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; CI, confidence interval; IRF, independent review facility; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival

FIGURE 2.

Survival analyses in patients with an IPS of 4–7 at baseline by treatment arm at primary analysis (data cutoff, 20 April 2017). Kaplan–Meier estimates of (A) PFS per the INV, and (B) OS. Hazard ratios, 95% CIs, and p values from log‐rank tests are presented; circles indicate censored data. A + AVD, brentuximab vedotin plus doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; CI, confidence interval; INV, investigator; IPS, International Prognostic Score; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival

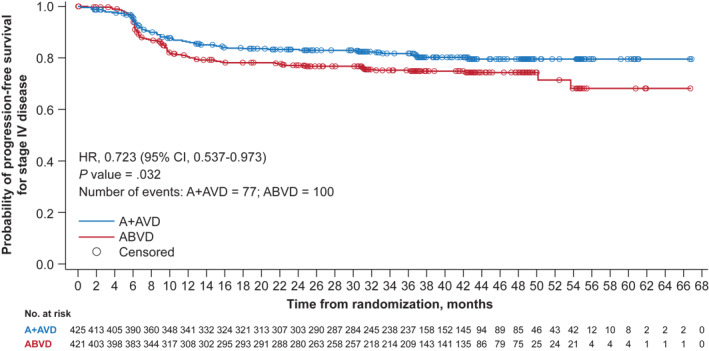

The benefit of A + AVD versus ABVD was maintained in an analysis of PFS per investigator with median follow‐up of 3 years (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.55–0.90; p = 0.005). Patients with Stage IV disease also benefited from treatment with A + AVD versus ABVD (HR, 0.723; 95% CI, 0.537–0.973; p = 0.032) with a 3‐year PFS rate of 81.8% (95% CI, 77.6%–85.3%) in the A + AVD arm and 74.9% (95% CI, 70.2%–78.9%) in the ABVD arm (a difference of 6.9%; Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Updated survival analyses in patients with Stage IV disease by treatment arm (data cutoff, 15 October 2018). Kaplan–Meier estimates of PFS per the INV. Hazard ratios, 95% CIs, and p values from log‐rank tests are presented; circles indicate censored data. A + AVD, brentuximab vedotin plus doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; CI, confidence interval; INV, investigator; IPS, International Prognostic Score; PFS, progression‐free survival

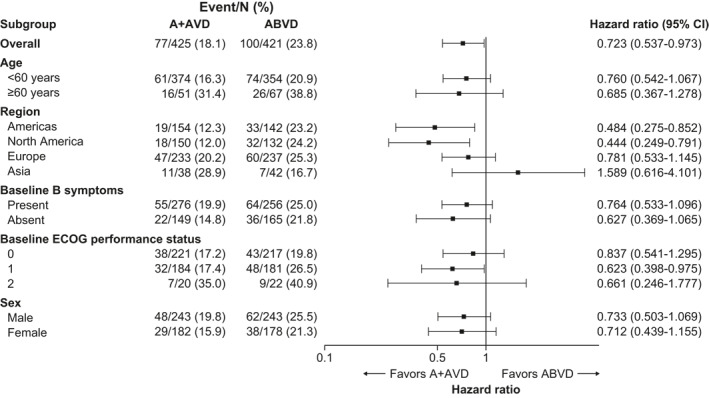

Patients with Stage IV disease experienced benefit with A + AVD across the majority of subgroups that were predefined for the ITT population in ECHELON‐1 (Figure 4). Notably, the PFS benefit per investigator at 3 years with A + AVD over ABVD was maintained in both younger (<60 years) and older (≥60 years) patients (HR, 0.760; 95% CI, 0.542–1.067 for patients aged <60 years; HR, 0.685; 95% CI, 0.367–1.278 for patients aged ≥60 years). In addition, the PFS benefit per investigator at 3 years with A + AVD over ABVD was noted in both PET2‐negative patients (A + AVD n = 379; ABVD n = 358) and ‐positive patients (A + AVD n = 34; ABVD n = 42) with Stage IV disease (HR, 0.732; 95% CI, 0.520–1.031 for PET2‐negative patients; HR, 0.727; 95% CI, 0.366–1.445 for PET2‐positive patients).

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for PFS per INV at 3 years for subgroups of patients with baseline Stage IV Hodgkin lymphoma (data cutoff, 15 October 2018). INV, investigator; PFS, progression‐free survival

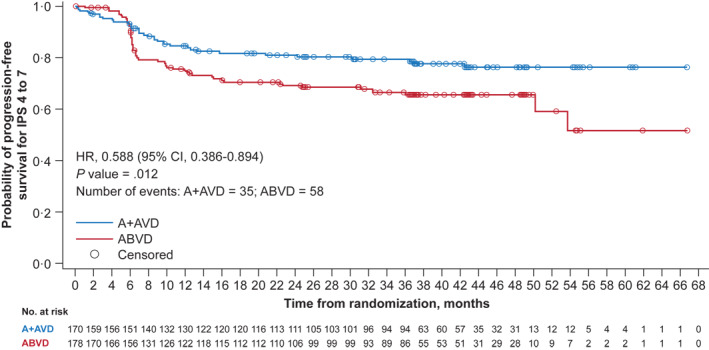

Patients with an IPS of 4–7 had results consistent with those in patients with Stage IV disease. The PFS per investigator at 3 years showed an improvement in the A + AVD arm compared with the ABVD arm, with an HR of 0.588 (95% CI, 0.386–0.894; p = 0.012; Figure 5). The 3‐year PFS rate in patients with an IPS of 4–7 was 79.6% (95% CI, 72.4%–85.1%) in the A + AVD arm and 65.7% (95% CI, 57.8%–72.4%) in the ABVD arm. The PFS benefit per investigator at 3 years with A + AVD over ABVD were noted in both PET2‐negative patients (A + AVD n = 144; ABVD n = 148) and ‐positive patients (A + AVD n = 16; ABVD n = 19) with an IPS of 4–7 (HR, 0.545; 95% CI 0.331–0.898 for PET2‐negative; HR, 0.510; 95% CI, 0.190–1.365 in PET2‐positive patients).

FIGURE 5.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of PFS per the INV by treatment arm at 3 years for patients with IPS of 4–7 (data cutoff, 15 October 2018). Hazard ratios, 95% CIs, and p values from log‐rank tests are presented; circles indicate censored data. A + AVD, brentuximab vedotin plus doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; CI, confidence interval; INV, investigator; IPS, International Prognostic Score; PFS, progression‐free survival

3.1. Safety

Safety data are from the primary analysis (data cutoff date, 20 April 2017; median follow‐up was 24.6 months), with the exception of peripheral neuropathy (PN) and secondary malignancy data, which had a median follow‐up of 37.1 months (data cutoff, 15 October 2018). During the study, most patients with Stage IV disease experienced ≥1 treatment‐related AE, regardless of treatment (Table 2). Safety results in patients with Stage IV disease and IPS of 4–7 were consistent with safety results reported in the overall population and did not change with longer observation. 12 Among patients with Stage IV disease, drug‐related AEs occurred in 96% in the A + AVD arm and 93% in the ABVD arm. Patients with Stage IV disease receiving A + AVD experienced more grade ≥3 treatment‐emergent AEs (83% vs. 67%), grade ≥3 drug‐related AEs (79% vs. 61%), and serious AEs (40% vs. 28%) than those receiving ABVD, respectively, but fewer of those receiving A + AVD died within 30 days of the last dose of frontline therapy (5 vs. 8 patients, respectively; Table 2). Patients with an IPS of 4–7 at baseline had similar safety profiles to those with Stage IV disease and the overall population (Table S2).

TABLE 2.

AEs reported in patients with Stage IV Hodgkin lymphoma

| AE, n (%) | A + AVD (n = 424) | ABVD (n = 413) |

|---|---|---|

| Any AE | 416 (98) | 403 (98) |

| Drug‐related AE | 408 (96) | 383 (93) |

| Grade ≥3 AE | 352 (83) | 278 (67) |

| Drug‐related grade ≥3 AE | 336 (79) | 250 (61) |

| Serious AE | 170 (40) | 114 (28) |

| Drug‐related serious AE | 140 (33) | 83 (20) |

| AE resulting in study drug or dose discontinuation | 44 (10) | 66 (16) |

| AE resulting in dose modification a | 268 (63) | 184 (45) |

| Dose held | 26 (6) | 22 (5) |

| Dose interrupted | 12 (3) | 20 (5) |

| Dose reduced | 121 (29) | 41 (10) |

| Dose delayed | 204 (48) | 138 (33) |

| On‐study death | 5 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Death due to drug‐related AE | 5 (1) | 5 (1) |

Abbreviations: A + AVD, brentuximab vedotin plus doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; AE, adverse event.

Table is based on the number of patients, and one patient might have multiple AEs.

Consistent with results in the overall population, more patients with Stage IV disease in the A + AVD arm experienced any‐grade treatment‐emergent PN (67% vs. 40%), neutropenia (71% vs. 55%), and febrile neutropenia (19% vs. 8%) than those in the ABVD arm.

More patients with an IPS of 4–7 in the A + AVD arm experienced PN (69% vs. 45%), neutropenia (66% vs. 55%), and febrile neutropenia (23% vs. 9%) than those in the ABVD arm.

PN was managed with dose modification and was generally reversible. At a data cutoff of 15 October 2018 (median follow‐up, 36.1 months after end of treatment), PN resolution and improvement rates had continued to increase in patients who were treated with A + AVD or ABVD. At last follow‐up, the majority of patients with Stage IV disease in the A + AVD arm (80%) and ABVD arm (85%) had experienced resolution of or improvement in PN (Table 3); the proportion of patients with resolution of or improvement in PN was similar in the groups of patients with an IPS of 4–7. Consistent with reports for the overall population, the rates of neutropenia and febrile neutropenia in these subgroups were reduced in patients who received primary granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor (G‐CSF) prophylaxis (Table S3). The use of primary G‐CSF prophylaxis is recommended for all patients receiving the A + AVD combination. 11 In the ABVD arm, pulmonary toxicity by standardized MedDRA queries were reported in 27 of 413 patients (7%) with Stage IV disease and in 5% of patients with an IPS of 4–7 (Table S4). In the A + AVD arm, pulmonary toxicity events by standardized MedDRA queries were reported in eight of 424 patients (2%) with Stage IV disease and two of 168 patients (1%) with an IPS of 4–7. Among patients with Stage IV disease, deaths due to pulmonary toxicity were reported in three of 413 patients who received ABVD and no patients who received A + AVD.

TABLE 3.

PN resolution in Stage IV patients (median follow‐up, 36.1 months postend of treatment)

| Outcome of PN events at last follow‐up, n (%) | A + AVD (n = 283) | ABVD (n = 165) | Total (N = 448) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum severity grades, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 58 (20) | 27 (16) | 85 (19) |

| 2 | 30 (11) | 14 (8) | 44 (10) |

| 3 | 9 (3) | 3 (2) | 12 (3) |

| 4 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Resolution a of or improvement b in PN events | 225 (80) | 140 (85) | 365 (81) |

| Resolution a of all PN events | 185 (65) | 121 (73) | 306 (68) |

| Improvement b in PN events | 40 (14) | 19 (12) | 59 (13) |

| No resolution of or improvement in any PN events | 58 (20) | 25 (15) | 83 (19) |

Abbreviations: A + AVD, brentuximab vedotin plus doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; PN, peripheral neuropathy.

Defined as event outcome of “resolved” or “resolved with sequelae.”

Resolution implies improvement. In addition, for events that were not resolved, improvement was defined as decrease by ≥1 grade from the worst grade, with no higher grade thereafter.

In the overall ECHELON‐1 study population at a median follow‐up of approximately 3 years, 34 patients developed secondary malignancies, including 14 in the A + AVD arm (2.3%) and 20 in the ABVD arm (3%). A total of three patients developed secondary AML— two in the A + AVD arm and one in the ABVD arm. One patient in the ABVD arm and none in the A + AVD arm developed secondary myelodysplastic syndrome. In the A + AVD arm, solid malignancies occurred in five patients and other hematologic malignancies in five patients. In the ABVD arm, solid malignancies occurred in six patients and hematologic malignancies in seven patients. In patients with Stage IV disease, secondary malignancies occurred in eleven of 425 patients (2.6%) in the A + AVD arm (four solid and seven hematologic malignancies) and 14 of 421 patients (3.3%) in the ABVD arm (five solid and nine hematologic malignancies). Among patients with an IPS of 4–7, secondary malignancies occurred in five of 168 (3.0%; two solid and three hematologic malignancies) and 10 of 175 (5.7%; three solid and seven hematologic malignancies) patients receiving A + AVD and ABVD, respectively.

4. DISCUSSION

Although cHL has a high 5‐year failure‐free survival rate of more than 80% in all disease stages, patients with Stage IV disease treated with ABVD have a comparatively lower 5‐year failure‐free survival rate (76%).1, 7, 14, 15 Similarly, patients with an IPS of 4–7 at diagnosis often have a poor prognosis. 16

The ECHELON‐1 trial showed a statistically significant improvement in modified PFS by the IRF and additional improvement in PFS per the investigator in patients with stage III or IV disease who received A + AVD compared with those who received ABVD. 12 In this analysis, we focused on patients at a high risk of treatment failure as indicated by baseline disease characteristics, including Stage IV disease and an IPS of 4–7. This subgroup analysis included additional efficacy (2‐year PFS, OS) and safety results and updated 3‐year PFS in the context of the ITT population. The results demonstrated that the value of adding BV to first‐line treatment for patients with advanced HL is greater in high‐risk patients and demonstrated that high‐risk features may help all clinicians who treat advanced stage HL to predict poor treatment outcomes with standard ABVD, which can be partially overcome with the addition of BV.

At the primary analysis, an improvement was observed in the risk of a modified PFS event in both high‐risk patients who received A + AVD versus those who received ABVD. Furthermore, an improvement in OS was noted in patients with Stage IV disease in favor of A + AVD. The results of the primary analysis strongly supported the superiority of A + AVD over ABVD in patients with Stage IV disease as well as those with a high IPS. The safety profile of A + AVD observed in the two high‐risk subgroups was comparable to that observed in the overall safety population, and no new safety signals were identified. Importantly, patients with high‐risk cHL did not experience an increased incidence or severity of AEs, consistent with what was observed in the overall safety population.

Since the primary analysis, this patient population has also been assessed at a median follow‐up of approximately 3 years. A previously published analysis of the ITT population at 3 years demonstrated the durable benefit of A + AVD versus ABVD in patients independent of age, disease stage, or risk‐factor score without requiring change of therapy or exposure to bleomycin. 13 In this analysis of patients with Stage IV disease, an analysis of PFS by investigator demonstrated an improvement that was maintained at 3 years with A + AVD versus ABVD, with a reduction in the risk of a PFS event of 28% (HR, 0.723; 95% CI, 0.537–0.973). In addition, benefit based on PFS per investigator assessment in patients with an IPS of 4–7 was also maintained at a median follow‐up of 3 years (HR, 0.588; 95% CI, 0.386–0.894). 13 These updated results are consistent with the results of the primary analysis and further support the use of A + AVD as a meaningful treatment option for patients with high‐risk cHL.

Upon treatment outcome being stratified in patients with Stage IV disease according to PET2 status, both PET2‐negative and PET2‐positive cohorts had a better outcome in the experimental versus the standard arm (HR, 0.732; 95% CI 0.520–1.031 for PET2‐negative patients; HR, 0.727; 95% CI, 0.366–1.445 for PET2‐positive patients). PET‐2‐negative and PET‐2‐positive cohorts with IPS 4–7 also had a better outcome in the experimental versus the standard arms (HR, 0.545; 95% CI, 0.331–0.898 in PET2‐negative patients; HR, 0.510; 95% CI, 0.190–1.365 in PET2‐positive patients).

In recent years, multiple clinical trials, including SWOG S0816, RATHL, and GITIL/FIL HD 0607, have focused on improving outcomes in patients with advanced stage cHL by managing patients who are initiated on ABVD and have a positive PET2 result with escalation of therapy to BEACOPPesc.17, 18, 19 The comparison of ECHELON‐1 with studies of BEACOPPesc or PET response–adapted BEACOPPesc‐based regimens is difficult because of important differences in inclusion criteria (different proportions of patients with stage II disease, different age ranges), PET interpretation rules, and study endpoints (PFS vs. modified PFS). In addition, although the use of BEACOPPesc has shown superior 3‐ and 5‐year PFS compared with standard ABVD in PET2‐positive patients, it comes at the cost of increased short‐ and long‐term toxicities, including infertility and secondary malignancies. 4 In the primary SWOG S0816 study, secondary malignancies were observed in 6% of PET2‐positive patients receiving BEACOPPesc or BEACOPP‐14 with 3.3 years of follow‐up, and the rate increased to 14% with 5.9 years of follow‐up. 17 In the RATHL and HD0607 trials, the rate of secondary malignancies was lower, but the follow‐up in these two studies was shorter.16, 17 In ECHELON‐1, the rate of secondary malignancies on the A + AVD arm was 2.8% (Stage IV, 2.6%; IPS of 4–7, 3.3%) and 3% in the ABVD arm (Stage IV, 3.3%; IPS of 4–7, 5.7%). Although follow‐up is ongoing, these secondary malignancy data from ECHELON‐1 suggest that the rate with A + AVD did not exceed that with ABVD; hence, A + AVD could provide an effective alternative to BEACOPPesc that could potentially spare patients the associated long‐term toxicities.

One notable limitation to these analyses is that although these subgroups were prespecified, they were not alpha‐controlled; thus, p values cannot be adjusted for inferential purposes. Additionally, there is a potential for a close interaction between subgroups to confound the observed treatment benefit. For example, the presence of Stage IV disease is one of the seven risk factors included in the IPS, resulting in a higher chance that a patient will be in both subgroups. 20 Overlapping of other risk factors, such as extranodal involvement, advanced age, or subtype, may also exist. It is therefore difficult to ascertain the exact attribute or attributes that determine greater benefit with A + AVD.

In ECHELON‐1, A + AVD provided clinically meaningful improvements in modified PFS, with an acceptable safety profile, supporting a favorable benefit‐risk balance in the first‐line treatment of adult patients with cHL, including those with Stage IV disease or an IPS of 4–7. With continued follow‐up of PFS per investigator, a consistent benefit with A + AVD over ABVD has been observed across prespecified subgroups, including patients with high‐risk characteristics.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Martin Hutchings received research funding and consulting fees from Takeda, Roche, and Celgene. John Radford received consulting fees from ADC Therapeutics, Takeda, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Novartis. Stephen M. Ansell received research funding from Takeda, Seattle Genetics, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Affimed, Regeneron, LAM Therapeutics, and Trillium. Anna Sureda participated in educational activities for Takeda, BMS, Roche, Gilead, and Novartis and received honoraria from Takeda, Celgene, Janssen, Gilead, and Novartis. Joseph M. Connors received honoraria from Seattle Genetics and Takeda. Hirohiko Shibayama received grants and honoraria from Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Janssen, Nippon Shinyaku, Ono, Novartis, and Takeda; received grants from Astellas, Teijin, MSD, Shionogi, Sumitomo Dainippon, Taiho, and Mundipharma; and received honoraria from Chugai, Kyowa Kirin, Otsuka, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Fujimoto, Sanofi, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Pfizer. Jeremy S. Abramson received research funding and consulting fees from Seattle Genetics. Neil S. Chua received an honorarium from Seattle Genetics. Jonathan W. Friedberg received research funding from Seattle Genetics, consulting fees from Bayer and Acerta, and travel expenses from Roche. Ann Steward LaCasce received consulting fees from Seattle Genetics. Gerald Engley is an employee of Seattle Genetics. Keenan Fenton is an employee of Seattle Genetics and holds stock or stock options in Seattle Genetics. Hina Jolin is an employee of Takeda. Rachael Liu is an employee of Takeda. Ashish Gautam is an employee of Takeda. Andrea Gallamini received consulting fees from Takeda. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Martin Hutchings contributed to the study design, patient accrual, data collection, data interpretation, data analysis, manuscript writing, critical revision of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript. John Radford contributed to manuscript writing and final approval of the manuscript. Stephen M. Ansell contributed to the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of the manuscript. Árpád Illés contributed to manuscript writing and final approval of the manuscript. Anna Sureda contributed to data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of the manuscript. Joseph M. Connors served on the trial committee and contributed to the study design, data collection, data interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of the manuscript. Alice Sýkorová contributed to manuscript writing and final approval of the manuscript. Hirohiko Shibayama contributed to data collection and final approval of the manuscript. Jeremy S. Abramson contributed to manuscript writing and final approval of the manuscript. Neil S. Chua contributed to patient enrollment and oversight, data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation. Jonathan W. Friedberg contributed to patient enrollment and oversight, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and final approval of the manuscript. Jan Kořen contributed to manuscript writing and final approval of the manuscript. Ann Steward LaCasce contributed to manuscript writing and final approval of the manuscript. Lysiane Molina contributed to manuscript writing and final approval of the manuscript. Gerald Engley contributed to data collection and manuscript writing. Keenan Fenton contributed to data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript writing. Hina Jolin contributed to protocol writing, data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation. Rachael Liu contributed to data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation. Ashish Gautam contributed to data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation. Andrea Gallamini contributed to the study design, patient accrual, data collection, data interpretation, data analysis, manuscript writing, critical revision of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/hon.2838.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in this trial and their relatives, as well as the investigators and staff at all ECHELON‐1 clinical sites; the members of the independent data and safety monitoring committee and the independent review committee; Jeanenne Chung, Vijay Maharaj, Tae M. Hotniansky, and Andy Chi of Millennium Pharmaceuticals for their contributions to the conception and execution of the ECHELON‐1 trial; and Brad Imwalle, PhD, MBA, and Jackie Stone, PhD, of SciMentum, Inc., for writing support during the development of the manuscript, which was supported by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gordon LI, Hong F, Fisher RI, et al. Randomized phase III trial of ABVD versus Stanford V with or without radiation therapy in locally extensive and advanced‐stage Hodgkin lymphoma: an intergroup study coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (E2496). J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:684‐691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carde P, Karrasch M, Fortpied C, et al. Eight cycles of ABVD versus four cycles of BEACOPP escalated plus four cycles of BEACOPPbaseline in stage III to IV, international prognostic score >/= 3, high‐risk Hodgkin lymphoma: first results of the phase III EORTC 20012 intergroup trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2028‐2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Federico M, Luminari S, Iannitto E, et al. ABVD compared with BEACOPP compared with CEC for the initial treatment of patients with advanced Hodgkin's lymphoma: results from the HD2000 Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio dei Linfomi Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:805‐811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Engert A, Diehl V, Franklin J, et al. Escalated‐dose BEACOPP in the treatment of patients with advanced‐stage Hodgkin's lymphoma: 10 years of follow‐up of the GHSG HD9 study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4548‐4554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wongso D, Fuchs M, Plutschow A, et al. Treatment‐related mortality in patients with advanced‐stage Hodgkin lymphoma: an analysis of the German Hodgkin study group. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2819‐2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. von Tresckow B, Kreissl S, Goergen H, et al. Intensive treatment strategies in advanced‐stage Hodgkin's lymphoma (HD9 and HD12): analysis of long‐term survival in two randomised trials. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5:e462‐e473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cancer Stat Facts: Hodgkin Lymphoma; 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/hodg.html. Accessed June 22, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Younes A, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Results of a pivotal phase II study of brentuximab vedotin for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2183‐2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen R, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Five‐year survival and durability results of brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2016;128:1562‐1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moskowitz CH, Walewski J, Nademanee A, et al. Five‐year PFS from the AETHERA trial of brentuximab vedotin for Hodgkin lymphoma at high risk of progression or relapse. Blood. 2018;132:2639‐2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Younes A, Connors JM, Park SI, et al. Brentuximab vedotin combined with ABVD or AVD for patients with newly diagnosed Hodgkin's lymphoma: a phase 1, open‐label, dose‐escalation study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1348‐1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Connors JM, Jurczak W, Straus DJ, et al. Brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for stage III or IV Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:331‐344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Straus DJ, Dlugosz‐Danecka M, Alekseev S, et al. Brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for stage III/IV classical Hodgkin lymphoma: 3‐year update of the ECHELON‐1 study. Blood. 2020;135:735‐742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:271‐289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koshy M, Fairchild A, Son CH, Mahmood U. Improved survival time trends in Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer Med. 2016;5:997‐1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hasenclever D, Diehl V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin's disease. International prognostic factors project on advanced Hodgkin's disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1506‐1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stephens DM, Li H, Schoder H, et al. Five‐year follow‐up of SWOG S0816: limitations and values of a PET‐adapted approach with stage III/IV Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2019;134:1238‐1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnson P, Federico M, Kirkwood A, et al. Adapted treatment guided by interim PET‐CT scan in advanced Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2419‐2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gallamini A, Tarella C, Viviani S, et al. Early chemotherapy intensification with escalated BEACOPP in patients with advanced‐stage hodgkin lymphoma with a positive interim positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan after two ABVD cycles: long‐term results of the GITIL/FIL HD 0607 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:454‐462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moccia AA, Donaldson J, Chhanabhai M, et al. International Prognostic Score in advanced‐stage Hodgkin's lymphoma: altered utility in the modern era. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3383‐3388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material