Abstract

Since first recognized in 1839, the pathogenesis of acne inversa (AI) has undergone repeated revisions. Although there is agreement that AI involves occlusion of hair follicles with subsequent inflammation and the formation of tracts, the histologic progression of this disease still requires refinement. The objective of this study was to examine the histologic progression of AI based on the examination of a large cohort of punch biopsies and excisional samples that were examined first by hematoxylin and eosin staining. The most informative of these samples were step‐sectioned and stained by immunohistochemistry for epithelial and inflammatory markers. Based on this examination, the following observations were made: 1) AI arises from the epithelium of the infundibulum of terminal and vellus hairs; 2) These form cysts and epithelial tendrils that extend into soft tissue; 3) Immunohistochemical staining demonstrates the epithelium of AI is disordered with infundibular and isthmic differentiation and de novo expression of stem cell markers; 4) The inflammatory response in AI is heterogeneous and largely due to cyst rupture. The conclusions of this investigation were that AI is an epithelial‐driven disease caused by infiltrative, cyst forming tendrils and most of the inflammation is due to cyst rupture and release of cornified debris and bacteria. Cyst rupture often occurs below the depths of punch biopsy samples indicating their use for analysis may give an incomplete picture of the disease. Finally, our data suggest that unless therapies inhibit tendril development, it is unlikely they will cause prolonged treatment‐induced remission in AI.

Keywords: diseases, hair follicle, Hidradenitis suppurativa, inflammatory skin, pathogenesis

1. INTRODUCTION

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a painful and debilitating inflammatory disease of the skin and subcutaneous tissues that originates from hair follicles. First recognized in 1839, its aetiology and pathogenic mechanisms remain a matter of debate. 1 , 2 Even nomenclature is a source of contention. Most widely used is “hidradenitis suppurativa” although there is uniform agreement that this disease does not represent a primary hidradenitis. 3 , 4 , 5 Another suggested name is “acne inversa” (AI) so called because the disease most commonly affects the axillae, inguinal and perianal regions, the “inverse” of acne vulgaris, which is a true statement but does little to assist in understanding a disease that is not only anatomically but also clinically and histologically very different from acne vulgaris. 6 , 7 , 8 Still, it is accurate in what it purports to define and for that reason, is used herein.

The confusion about nomenclature is an indication there is still much to learn about AI. A recent review described eight major gaps in understanding and treatment of AI. Two of these gaps are fundamental: (1) a need to define the natural history of AI by determining the sequence of disease progression and (2) improved clinical‐pathologic correlation by defining the histologic features of specific AI lesions across the disease spectrum. 1 This report represents an attempt to fill these gaps without which any advancement in developing optimal therapies or understanding response outcomes (currently dependent on clinical assessments by methods such as the Hurley score) are greatly hindered.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Case selection

This study was based on the examination of excisional and punch biopsy samples from patients with AI. The diagnosis was established by either clinical presentation or by confirmatory histopathology reports. Samples included 177 formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded blocks representing 13 punch biopsies from eight patients and 157 blocks of excised tissue from 57 patients. Excisional tissues from eight patients were obtained prospectively. These were submitted intact, immediately placed in formalin and bread loafed during trimming so the entire sample could be evaluated histologically (Figure S1). In addition, diseased samples were compared with non‐lesional skin samples from six AI patients and excised normal skin samples collected during breast reduction surgery. Although samples were deidentified, available demographics are listed in Table S1. Clinical Hurley scores were not available, but all samples were from patients requiring surgical excision or in the case of the punch biopsies, patients with severe disease. Samples examined were obtained after approval by the Human Research Ethics Committees at each respective institution.

2.2. Pathologic evaluation

All samples were processed routinely and sectioned at 4 µm. Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed on a Leica ST5010 autostainer. All H&E stained slides were evaluated for a spectrum of histologic features attributed to AI. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 23 At the same time, the lesions were examined to identify a continuum of changes that defined the evolution of AI from histologic inception until fully developed. This examination demonstrated excisional samples were much more informative and their examination was emphasized. Because all the tissue from the eight prospectively obtained samples was trimmed for histologic assessment, the 99 blocks obtained from these patients were used to quantify the number of affected and unaffected follicles as well as to quantify tracts that were lined or not lined by epithelium. In addition, 20 blocks from these eight patients were selected as being most representative and instructive based on number of lesions at different stages of development and sample depth. These were sectioned deeper to evaluate the extent of the lesions and were evaluated for IHC markers on serial sections that defined epithelial as well as inflammatory components of the disease and for the presence of proliferation and bacteria (Gram's stain) (Table S2). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on a Leica Bond RX automated immunostainer. All slides were digitized using a Pannoramic 250 scanner (3DHISTECH Ltd.).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Epithelial changes

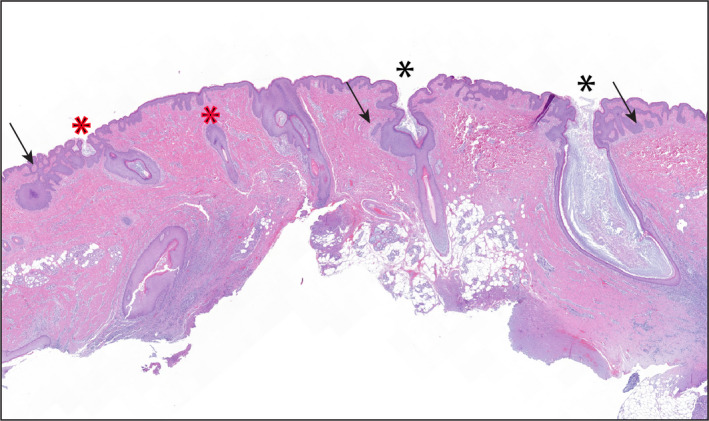

The earliest histological change in AI was hyperplasia of the outer root sheath of the follicular infundibula, associated with a dilated lumen filled with cornified debris. Luminal hair shafts were occasionally present. This alteration was common in excisional samples, involved vellus and terminal hair follicles, and multiple early lesions could be present in a single section. (Figure 1), From these diseased infundibula, protuberances of the cystic infundibulum (defined as “tendrils”) extended laterally and beneath the sebaceous duct (the anatomic limit of the infundibulum) (Figures 2 and 3). Quantitation of infundibular regions from large, completely excised samples identified 356 follicles; from these, 198 follicles (56%) had histologic evidence of early AI changes (defined as hyperplasia of the infundibular outer root sheath with early tendril formation and often, keratin plugging with infundibular dilation) or more advanced follicular lesions.

FIGURE 1.

An excisional biopsy from a patient with AI. All infundibula in this section demonstrate early to progressive lesions defined by hyperplasia of infundibular outer sheath epithelium (black asterisks define terminal follicles, red asterisks define vellus follicles). There are also small tendrils extending from the hyperplastic epithelium (arrows). H&E stain, magnification 1.4x

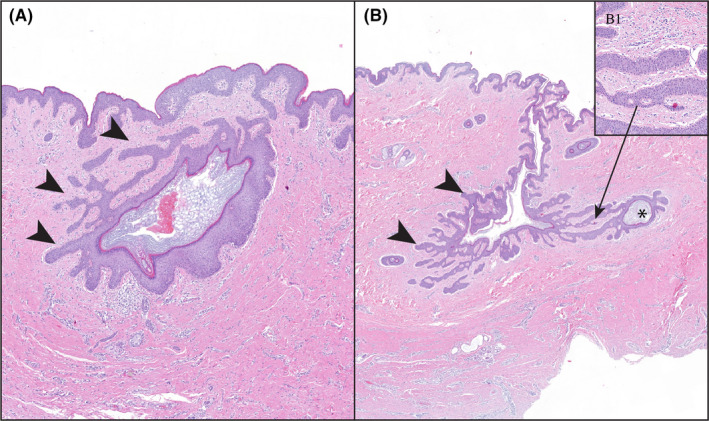

FIGURE 2.

Tendrils are a defining feature of AI. They develop early in the disease before rupture of the infundibular lumen. (A) Early tendrils (arrowheads) from a follicular infundibulum. (B) More extensive and deeper extension of tendrils (arrowheads) with the formation of a new cyst (asterisk). (B). Higher power of tendrils defining their growth does not require substantive inflammation to progress. H&E stain, magnification A = 3.6, B = 1.6x, B1 = 16.5x

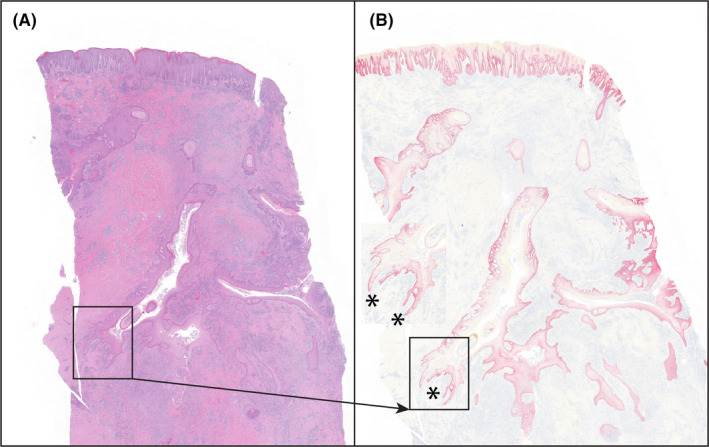

FIGURE 3.

Severely inflamed Hurley stage III. There are many continuous and interconnecting tendrils/cysts extending into deeper soft tissues (asterisks), best defined by IHC staining for K5 in (B). The presence of tendrils extending into deep soft tissues indicts that they can develop in spite of intense inflammation. (A) = H&E stain; (B) = immunostaining for K5, fast red chromogen, haematoxylin counter stain, magnification both images, 0.7x

As lesions progressed, tendrils extended deeper into the dermis and subcutaneous fat. In fully developed lesions, best defined on continuous sections, there was an interconnecting labyrinth of infiltrative keratinizing epithelium that formed cysts away from the infundibula from which they arose. Tendrils developed independent of substantive inflammation and represented a defining and distinctive feature of AI (Figure 2). In deeper regions in fully developed AI, there were separations in soft tissues, usually associated with areas of abscessation. These “tunnels” typically were arranged in the same labyrinthine pattern of intact infiltrative tendrils and were consistent with necrosis of the epithelial lining as the inflammation often contained keratin shards and/or remnants of the lining epithelium (Figure 3). Fully developed lesions generally extended deep in the dermis below the limits of a standard biopsy punch (Figure S4). Because the large, excisional samples included deeper soft tissues, they were also used to define tunnels and tendrils. In these 99 blocks, deeper lesions of AI were identified in 85 (86%). Of these, 17 (20%) of the tunnels were devoid of any epithelial lining, 65 (76%) were partially epithelial‐lined and 3 (4%) were composed of tendrils and cysts without tunnel formation.

There was no histologic evidence that apocrine glands or ducts were associated with the development of AI at any stage of the disease.

To further define the epithelial component of AI, the expression of a variety of epithelial proteins and the proliferation marker, Ki‐67 were defined by IHC and compared with hair follicles identified in non‐diseased skin samples (Table 1). Keratin 5 (K5) expression was used as a consistent epithelial marker throughout disease development (Figure S5).

TABLE 1.

Expression of analysed epidermal proteins in acne inversa

| Epithelial protein | Epidermis | Hair follicle | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | HS | Infundibulum a | Subinfundibulum b | |||

| Normal | HS | Normal | HS | |||

| Cytokeratin 5 | Diffuse (B,S) | Diffuse (B,S) | Diffuse (B,S) | Diffuse (B,S) | Diffuse (B,S) | Diffuse; defines extent of lesion (B,S) |

| Cytokeratin 10 | Diffuse (S,G) | Diffuse (S,G) | Diffuse (S,G) | Diffuse (S,G), decreases with parakeratosis | Diffuse (S,G) | Limited to cornifying epithelium; decreases as granular layer decreases (S,G) |

| Cytokeratin 15 c | Variable. B,S | Variable BS often more intense than normal, staining to mid‐spinous layer | Variable B,S (similar to epidermis) | Variable B,S (similar to epidermis) | Intense B,S expression in lower half of subinfundibular region | Variable expression BS,, usually lighter than epidermis/infundibum slightly more common in deep areas with cornifying epithelium |

| Cytokeratin 17 | Not expressed | Variable, often intense (S, G) expression adjacent to opening of sinus tracts | Not expressed | Strong S,G expression when part of sinus tracts | Diffuse (S,G) | Variable, more intense in non‐cornifying epithelium (S,G); could appear inverse of K15 staining |

| Cytokeratin 19 c | Not expressed c | Not expressed | Not expressed | Rare when expressed, present in SG | Intense (B,S) expression in lower half of subinfundibular region (similar to K15) | Variable, often overlapping but less extensive than K17 (B,S) |

| Nestin c | Not expressed | Variable, faint B,G | Not expressed | Variable | Variable, minimal B,S | Variable, often overlapping with cytokeratin 17 (B,S) |

B, basal cell layer; G, stratum granulosum; S, stratum spinosum.

Outer rooth sheath above sebaceous gland duct.

Outer rooth sheath below sebaceous gland duct.

Putative hair follicle stem cell markers.

Regions of the hair follicle are defined by patterns of epithelial marker expression including infundibulum (K10), outer root sheath (K17, K19, nestin) and stem cells (K15, K19, nestin). Tendrils and cysts, even those in deep soft tissues, had cornifying regions highlighted by K10 (a marker of infundibular differentiation) alternating with non‐cornifying regions demonstrating outer root sheath differentiation (K17, K19, nestin). Early lesions (i.e., those above the sebaceous duct) also expressed K10. Hyperplastic ostial openings of draining tracts displayed K10 expression with occasional evidence of outer root sheath immunophenotype. Open spaces in tissues (“tunnels”) often intermixed with suppurative inflammation generally contained K10 positive squames, consistent with cyst/tendril necrosis. The expression of nestin, K19 and K15 were considered evidence of stem cell differentiation. This was especially true for nestin and K19 expression which were generally in deep, non‐cornifying regions structures and were co‐expressed with K17. Stem cell immunopositivity, coupled with the variability, and intermixing of the other epithelial markers were consistent with a disordered pattern of cornification. In none of the samples examined, there was evidence of hair matrix differentiation.

Ki67 was diffusely expressed among basal cells and in regions, a few cell layers suprabasally. The leading edge of the tendrils often was positive for this proliferation marker but was not increased when compared to lateral tendril walls, the cyst walls or the epidermis (Figure S6).

3.2. Characterization of the inflammatory reaction in AI

The hyperplastic infundibula were associated with a variable but generally mild, mixed mononuclear inflammatory response, and rupture of cysts was uncommon when cystic infundibula were above sebaceous gland ducts (Figure 1). At a minimum, this inflammatory response was present from early through fully developed lesions. However, intense regions of inflammation required cyst rupture. This was best defined in excisional samples where the lesion was limited to isolated, clearly defined, unconnected, ruptured cysts consistent with Hurley stage I. Here, the cyst was surrounded by a severe inflammatory reaction that infiltrated the cornified centre (Figure S7). In fully developed (Hurley stage II or III) lesions with more diffuse inflammation, a ruptured cyst or tendril may not be clearly defined but its prior presence was confirmed by epithelial remnants of the cyst wall and/or shards of K10+ keratin in the inflammatory milieu (Figure S8). Presumptively, although cysts might rupture from mechanical trauma, in some regions, neutrophils were identified breaching the walls of cysts that contained luminal bacteria suggesting a role for bacteria in the pathogenesis of AI (Figure S9). Associated with the inflammation was active fibroplasia with neovascularization. Peripherally, the cellularity of fibroblasts decreased with replacement by abundant collagenous stroma representative of the scarring noted as a clinical feature of AI.

Even without the benefit of IHC, the heterogeneity of the inflammatory reaction could be defined. Neutrophils, lymphocytes (including plasma cells), macrophages (sometimes epithelioid or multinucleate), eosinophils and mast cells were largely intermixed; however, the composition and intensity of the inflammatory milieu changed depending on proximity to ruptured cysts. The most abundant inflammatory cells associated with cyst rupture were neutrophils (defined by MPO); however, after this early neutrophilic infiltration, there was little consistency in the types of inflammatory cells associated with active regions of inflammation around ruptured cysts other than foci of abscessation where again, neutrophils predominated (Figure S10).

The most abundant cells were IBA‐1+ (generally considered a marker for monocyte/ macrophages). These cells were diffusely and densely scattered in soft tissues around regions of cyst rupture. Dendritic cells, defined by CD11c expression, were much less abundant and were only identified where IBA‐1 immunopositivity was present suggesting proximity was mandatory or that the CD11c‐positive cells represented a subpopulation of IBA‐1+ cells. CD4+ cells were also diffusely scattered in highly inflamed areas. CD8+ cells were a minor component of the infiltrate. Both CD4+ and CD8+ cells demonstrated infiltration into epithelial structures.

B cells as defined by CD20 immunopositivity were diffusely scattered but were also present as lymphoid nodules whereas CD138 expressing plasma cells were more diffusely intermixed with other inflammatory cells and were more abundant. Although there was variability, in most samples examined, B cells (CD20+ plus CD138+ cells) at least as common as T cells (small CD4+ plus CD8+ cells) (Figure S10).

Examination of peripheral regions, above or lateral to highly inflamed areas of tissue, revealed not only less inflammation, but also a different composition of immune cells (Figure S11). Here, CD4+ and IBA1+ cells comprised the most abundant cell population and CD8+ T cells, B cells and CD11c+ cells and neutrophils were relatively rare with plasma cells being more abundant in the superficial dermis than CD20 cells+. Mast cells (defined by c‐kit immunopositivity) and eosinophils (defined morphologically) displayed variable distribution, from moderately abundant to uncommon.

4. DISCUSSION

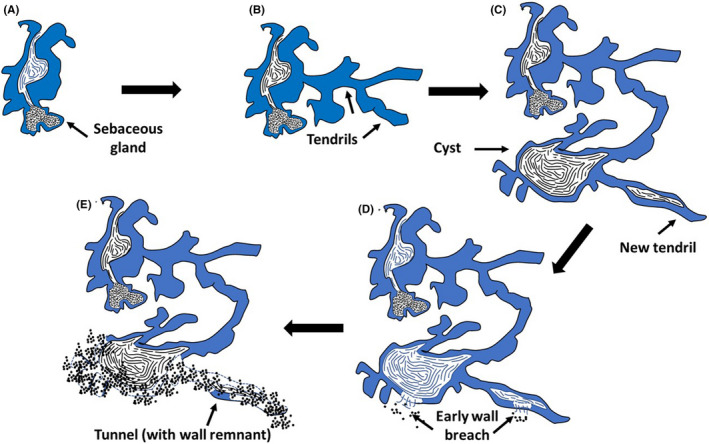

Based on our analysis, AI originates from the infundibulum of hair follicles with extension by cyst‐forming tendrils into deeper soft tissues. The inflammatory response is largely secondary to recurrent rupture of continuously forming keratin‐filled tendrils and cysts that contain bacteria (Figure 4). The defining histologic feature of AI is the presence of tendrils—extensions of squamous epithelium that infiltrate into surrounding tissues. These have been mentioned and depicted in previous reports but not particularly emphasized. 4 , 19 , 21 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 A prevailing view describes tendrils (often called sinus tracts or tunnels) as a late feature of the disease (i.e., developing after a cyst has ruptured) and that they form from epithelial remnants of ruptured cysts. 9 , 19 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 In contrast, our observations concur with those of Kurokawa et al, 24 2008, that the tendrils developed early in the disease. In addition, inflammatory lesions seldom developed in the acroinfundibulum (the region of the infundibulum closest to the to the external opening of the follicle). 9 , 19 , 23 Finally, there was no histologic evidence that tendril development was inhibited or stimulated by inflammation.

FIGURE 4.

Proposed histologic progression of AI (not to scale). (A) Lesions start with hyperplasia of the infundibular outer root sheath. (B) From the infundibulum, branching tendrils extend in adjacent soft tissues. (C) As lesions evolve, cornified cysts form and from these cysts, new tendrils form that can have cornified lumens. (D) Although mild inflammation can occur at all stages of development, substantive inflammation is associated with a breach in the cyst or lumen wall and extrusion of luminal cornified debris and bacteria. (E) As inflammation intensifies cysts can be destroyed and necrotic tendrils result in the formation of non/minimally epithelial‐lined tunnels

The transition of normal infundibula to those with histologic features of AI is extensive in patients requiring surgical excision. Fifty‐six per cent of follicles examined from eight, large excisional samples in which all tissue was processed had evidence of this transition, and this was an underestimate as not all follicles counted had infundibula. These data indicate that chronic AI is a diffuse and active, albeit generally regional disease consisting of tunnels that originated from these early infundibular changes. Why some of these follicles form infiltrative, cyst‐forming tendrils whereas most do not, remains to be determined. On examination of deeper, soft tissue lesions in the same blocks used to define early follicular changes, evidence of tendrils and tunnels were present in 86% of the blocks, an indication of extensive and destructive features of longstanding AI. In addition, 76% of tunnels had regions of epithelial lining demonstrating an associated pathogenesis. This observation coupled with the evolution of tendrils that formed cysts with subsequent rupture defined the progressive nature of AI.

From a disease progression perspective, it is helpful to consider “tendrils” as intact, dissecting epithelial cords, often with luminal cornification. When a tendril dilates, being filled with corneocytes, the term “cyst” is appropriate. The term “tunnel” represents a late feature of fully developed and highly inflamed regions where there is extensive necrosis of tendril epithelium and the path of the tendril is lined by none or occasional areas of intact epithelium. 30 Histologically, tunnels appear as a separation of soft tissues. The visualized separation is because tunnels contain fluid, largely suppurative inflammation and often cornified debris that could be defined by K10+ immunostaining.

As lesions resolve, these areas close and are replaced by connective tissue. The extensive inflammation of soft tissues in Hurley stage II or III is a reason why scarring is extensive as AI resolves. Although it is possible that new tendrils can develop from remnants of cyst wall epithelium that focally line tunnels after cyst rupture, this does not represent a major mechanism of tendril formation.

Kurokawa also believed that an “invagination of the epidermis may result in the formation of infundibulum‐like epithelium that protrudes into the deep dermis as an epidermal cyst.” 24 Foci suggesting this phenomenon were noted; however, when examined by deeper sections in our cohort, these epidermal invaginations never evolved into fully developed lesions of AI and all fully developed lesions of AI could be traced back to a hair follicle.

AI has also been described as a disease exclusively of terminal hair follicles 9 ; however, we regularly observed cyst‐forming tendrils arising from vellus hairs. This is in concurrence with Kurokawa's statement “It is very dubious that AI predominately affects terminal hair follicles”. 24 Whether or not vellus hairs have apocrine glands or whether all terminal follicles in apocrine‐gland bearing skin have apocrine glands remains undefined. 31 , 32 , 33 In this study, deeper sections of affected vellus hairs appeared to lack duct insertions in the infundibulum suggesting AI is not only not a hidradenitis, it may not even exclusively be a disease of apocrine follicles. This could explain why AI can occur in sites devoid of apocrine glands. 34 As has been reported previously, even on serial sections, there was no evidence that apocrine glands or ducts were associated with the development of AI at any stage of the disease. 4

The expression of intermediate filament proteins by IHC further demonstrated the progression of AI. Early lesions with features of comedoes were K10+ and K5+, consistent with the expression pattern in the infundibulum. 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 As lesions evolved with the formation of tendrils and cysts, the expression pattern was more random with the infundibular pattern described above intermixed with non‐cornifying regions defined by the expression of K17, K19 and nestin—proteins whose expression is normally restricted to the outer root sheath. 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 The expression of K15, K19 and nestin also suggested pluripotentiality as they have been described as stem cell markers. 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 Finally, this intermixing of infundibular and isthmic intermediate filament expression in deep, fully developed lesions and, occasionally, the presence of K17 and nestin in superficial draining tracts in AI indicated non‐neoplastic but disordered maturation.

In the first detailed assessment, IHC assessment of the sinus tracts in AI, Kurzen et al, 1999, defined three phenotypes of stratified squamous epithelium. 17 Type I was cornifying and K10+. Type II was non‐cornifying and negative for K10 but positive for K13 consistent with the pattern we observed with K17 staining. Type III was non‐cornifying, marked by the presence of K7 and K19, and was thought to be a response to highly inflamed regions.. 17 In this investigation, we were unable to confirm the association of K19 with inflammation. K19 immunopositivity was always present in deeper sub‐sebaceous duct regions which were typically more severely inflamed; however, there were regions with intense inflammation that were K19‐ and regions with minimal inflammation that were K19+. These results also differ from those of Kurokowa et al, 16 where K19 staining was not identified.

The inflammatory response associated with AI is extremely heterogeneous and composed of neutrophils, numerous CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, abundant CD20+ B cells, plasma cells, monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, eosinophils and mast cells and is most intense around ruptured cysts. The initial alteration in cyst rupture was defined by an infiltration of neutrophils extending into a cornified cyst lumen that occasionally contained Gram+bacteria. The concept of follicular wall fragility as an initiator of inflammation in AI was not confirmed. 9 , 45 Also, the thinning of the basement membrane in this region is not strong evidence of defective follicular support. 11 Dissolution of the basement membrane is a characteristic feature of cancer invasion and, although not analysed in this study, is more likely a feature of tendrils as they extend into deeper soft tissues. 46

Using an Occam's razor approach suggests that the inflammatory response in chronic AI represents largely a recurrent foreign body inflammatory response. This hypothesis does not dispute the immune‐mediated basis of this disease. That a large portion of the inflammatory response is directed against extruded, antigenic keratin, also agrees with the concept that AI is “autoimmune/autoinflammatory”, but these characterizations do little to explain the pathogenesis of AI.

From a histologic perspective, the inflammatory response in AI represents an activation of the entire panoply of the immune response: innate, adaptive, T cell, B cell, myeloid and dendritic cells in reaction to cyst‐forming, infiltrative tendrils that rupture, continuously releasing immunogenic keratin shards and commensal bacteria. 20 , 25 , 29

That a mild inflammatory reaction is present around early lesions has been used as evidence that inflammation is a primary driver for AI. 4 , 21 , 25 However, by the time a sample is obtained for histologic evaluation, the disease is already “chronic” meaning that the diverse immunologic reactions that are associated with AI are in play. Thus, a, residual superficial perivascular response would be expected. This would be especially true for samples that require surgical excision. 22 , 25 Second, any abnormal epithelial extension into the dermis whether of epidermal or follicular origin (i.e., tendrils) will incite inflammatory response. The inflammation associated with cutaneous neoplasms both malignant (squamous cell carcinomas) or benign (keratoacanthomas) has long been recognized. 47 , 48

Perhaps the main reason why the aetiology of AI remains undefined is because it has such unique clinical and histologic features. Described as an “infiltrative growth of proliferating non‐malignant keratinocytes,” AI has some overlapping features with a carcinoma. 49 Clinically, it does not respond well to anti‐inflammatory therapies and surgical excision may be curative. 50 , 51 , 52 Histologically, lesions are large, poorly circumscribed and asymmetric with tendril extension deep into soft tissues. Immunohistochemistry defines a disordered distribution of intermediate filaments and de novo expression of stem cells. Against AI being a malignancy is the absence of atypia, lack of vascular invasion or metastasis, the potential for spontaneous remission and evidence that it arises multifocally (i.e. not from a single clone). Most importantly, true malignancies have developed from patients with long standing AI. 53

Except for dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, we are unaware of any other inflammatory disease that can induce a response in epithelium that mimics the tendrils in AI. 54 , 55 , 56 Most analogous to AI are perianal fistulas associated with Crohn's disease (a disease that has been associated with AI). 57 , 58 However, the pathogenesis of perianal fistulas is different in that they are thought to arise from a deep ulcer and then re‐epithelialize, just the opposite of AI tendrils that extend into tissues and then undergo necrosis. 59 , 60

The tendril hypothesis also characterizes AI primarily as a disease where the most informative changes are generally beneath the depth of a standard biopsy punch. In this study, punch biopsies did not capture the tendrils and the labyrinth‐like interconnectivity or the heterogeneous inflammatory response (i.e., B cells, CD8+ cells, etc.) that characterize deeper, active disease. 24 This is why we limited detailed analysis to excisional samples. Relying on punch biopsies for molecular analyses may therefore lead to incomplete sampling of this process. A recent meta‐analysis of inflammatory cytokine associations with AI identified 19 references that included 564 individual AI patients and 198 controls. 61 Of these, only two studies (a total of 51 patients) based their examinations on excisional samples rather than biopsies. Both primarily relied on IHC, the first used quantitative PCR for molecular analysis and the second Western blot. 62 , 63 This may be a reason for the variance between measured levels of cytokines across the reported studies (only 21.8% of the 23 cytokines reported by more than one laboratory resulted in confirmatory conclusions). 61 These results indicate that the molecular biology of tendrils and active deep lesions have not been adequately examined. Because of the depth, random infiltration of tendrils and heterogeneity of the inflammatory response, future analyses of AI should take advantage of emerging spatial transcriptomic methods for gene expression and small sample proteomics to evaluate adequately sampled deep lesions. 64 , 65

The current development of medical therapies for AI is based largely on inhibiting the inflammatory component of the disease. 66 The evidence presented here suggests that if infiltrative tendrils are the driving force for AI and if tendrils develop independently of the intensity of the inflammatory reaction, then anti‐inflammatory therapies will be ameliorative but not curative. This is demonstrated in a double‐blind placebo‐controlled investigation in the use of adalimumab to treat AI where there was no clinical improvement compared with the placebo group after week 2 of a 12‐week study and when disease progression was followed for an additional 24 weeks there was no difference between the two groups. 67 From the tendril hypothesis perspective, we propose that the effects of anti‐transforming growth factor alpha treatments work primarily by diminishing the inflammatory component of the disease and may not adequately control the tendril infiltration. We contend that anti‐inflammatory treatments are useful, but more effective therapies need to control tendril infiltration and achieve more effective, long‐term therapeutic response. Until then, surgical excision will remain the treatment of choice for Hurley stage II or III disease. 50 , 51 , 52

In conclusion, the data presented here provide evidence that AI is a unique, epithelial driven disease due to infiltrative, cyst‐forming tendrils and most of the inflammation can be explained by continuous cyst rupture and release of immunogenic cornified debris (Figure 4). The resultant inflammatory response is extremely heterogeneous with evidence of abundant T cell, B cell and myeloid (including mast cell) populations. That cyst rupture often occurs below the depths of samples obtained by punch biopsies indicates the analysis of punch biopsies may not be representative of the disease. Finally, although anti‐inflammatory treatments may help ameliorate AI, unless they impact on tendril infiltration, it is unlikely they will result in prolonged treatment‐induced remission.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge the support, technical expertise and advice provided by the pathologists and histotechnologists at the Abbvie Bioresearch Center.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Drs. M. Rosenblum, M. Lowe, J. Gudjonsson and P.W. Harms have served as consultants to AbbVie and have received research funding. Drs R.W. Dunstan, V. Todorović, V.E Scott, K.M. Smith, P. Honore, Ms. K.M. Salte and Mr. J.B. Wetter are employees of AbbVie.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RWD, KMS, VT, VES, KS, ML, MR, JEG and PH designed the study. RWD, KMS, VT, JBW, ML, MR and JEG performed the research. RWD, KMS, VT, JBW, PWH and REB analysed the data. RWD, KMS, VT and REB wrote the paper. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approval of its contents.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Table S1. Demographics and clinical data (where available) from the 58 subjects used in this study.

Table S2. Summary of the histochemical stains used in this study.

Figure S1. Gross photograph demonstrating the trimming technique used to examine all regions from a formalin‐fixed excisional sample of AI.

Figure S2. Early AI lesions. A. AI arises from the infundibula of the outer sheath as comedones surrounded by a hyperplastic epithelium. Inflammation is minimal (inset). B. As lesions evolve, cyst expands beyond infundibular boundaries (i.e., below the sebaceous gland duct). H&E stain, magnification: A = 5.1x (inset, 19.1x); B = 1.9x.

Figure S3. One hundred consecutive 5 μm sections were made from the lesion in Fig. 2B. A= Section 1, B= Section 37, C= Section 54, D = Section 90. What initially appears as a single cyst forms smaller, interconnected, smaller, cystic structures. There is a small, focally intense region of inflammation suggesting a future breach in the cyst wall (arrows). H&E stain, magnification, 1.4x.

Figure S4. Sections from several examples of AI demonstrating the depth to which lesions can extend. A. Infundibulum is the same depicted in Fig. 2B and C represent Hurley stage III disease. Asterisks represent the lumens of “tunnels” that are minimally lined by epithelium. The dotted line across figures measures 7 mm, the depth of a standard biopsy punch. In both C and D, the dermal lesions are lateral to their epidermal openings demonstrating the difficulty in defining dermal lesions by clinical examination of the skin surface. D1 represents a vellus hair from which the lesion arose. All figures (except D1) taken at the same magnification. H&E stain, Figures A‐D, magnification 0.5x, Figure D1, magnification 8x.

Figure S5. Demonstration of differential staining of intermediate filaments in AI. Row 1 defines changes in an early AI as defined by staining above the sebaceous gland duct. Row 2 is a low power view of intermediate filament expression across a fully developed (Hurley stage III) lesion. Row 3 defines expression of deep AI epithelium. K5 serves as a marker for epithelium throughout. K10 defines cornifying epithelium (normally there is no K10 expression below infundibulum), Staining for K15 is variable and may be expressed above and below the sebaceous duct. K17 is a proliferation marker and defines the proliferative features of AI. K19 and nestin can be considered stem cell markers that normally are expressed in the outer sheath epithelium below the infundibulum. H&E and IHC with fast red chromogen, hematoxylin counterstain, magnification Row 1=5x, Row 2=0.5x, Row 3=3.2x.

Figure S6. Ki67 immunohistochemistry of an infiltrating region of AI. There is diffuse expression primarily along the basal cell layer; however, the leading edge of a tendril (arrowhead) does not express greater proliferative activity than the lateral boundaries. IHC with fast red chromogen, hematoxylin counterstain, magnification 7.3x.

Figure S7. Two examples of changes consistent with Hurley stage I lesions. The inflammation is in the mid dermis and centered around a ruptured cyst with a cyst wall that is only partially intact (insets). The arrows in both figures are pointing to the remnants of the cyst wall. H&E stain, magnification A and B = 0.5x, Insets A1 = 3.3x, B1 = 2.9x.

Figure S8. Example of a deep region of Hurley stage III disease. There are numerous intersecting tunnels (asterisks). A. K5 staining demonstrates that there is a loss of epithelium lining these tracts. B and C. K10 staining demonstrate shards of keratin associated with these tunnels consistent with a ruptured cyst or necrosis of a cornifying tendril. A = H&E stain; B = immunostaining for K5, C and D, immunostaining for K10, all using fast red chromogen, hematoxylin counter stain, magnification A, B, C = 1.6x, D = 2.4x.

Figure S9. Early breach of cyst wall in the deep dermis of Hurley stage III disease. A and B. There is a migration of neutrophils through the cyst wall into the lumen containing cornified debris. Associated with the cornified debris are Gram + coccoid and coccobacillary bacteria (short arrows) that may be recognized by communication of keratinocytes/epidermal antigen processing cells. A and B, H&E stain; C, Grams stain, magnification A = 3.4x, B =15.2x, C = 40x.

Figure S10. Heterogeneous infiltration of inflammatory cells in an area of active inflammation in AI. The reaction contains abundant macrophages, dendritic cells, T‐cells, Bcells (including plasma cell) components. Neutrophils are not wellrepresented in this region although other areas contain abscesses composed primarily of MPO+ cell. The distribution of mast cells (c‐Kit) is representative where their numbers appear relative to inflammatory intensity and they are not present as a predominant inflammatory cell population. Eosinophils (asterisks) vary from sample to sample and in most samples were much less common than mast cells. H&E and expression defined by IHC identified by labels. IHC images: fast red chromogen and hematoxylin, magnification, H&E stain upper left, 0.9x, H&E stain lower right, 82.3x, all other figures, 10X.

Figure S11. Difference in inflammatory intensity and composition in a region of the superficial dermis over an active AI lesion compared to a deeper, more active inflamed area adjacent to an inflamed cyst (compare with Sup Fig 10). Monocytes/macrophages and CD4+ T‐cells are abundant but in comparison, CD8 cells, B‐cells (including plasma cells), CD11c+ dendritic cells, and neutrophils are underrepresented. Mast cells correspond with inflammatory intensity. Note that CD138 is expressed in basal/suprabasal keratinocytes and c‐Kit is expressed in melanocytes. Histochemical and IHC immunopositivity identified by labels. IHC images: fast red chromogen and hematoxylin, magnification, H&E stain upper left, 0.9x, all other figures, 10x.

Funding information

The design, study conduct and financial support for this research were provided by AbbVie. AbbVie participated in the interpretation of data, review and approval of the publication.

[Correction added on 18 February 2021, after first online publication: One of the author’s name has been updated in this version]

REFERENCES

- 1. Hoffman LK, Ghias MH, Garg A, Hamzavi IH, Alavi A, Lowes MA. Major gaps in understanding and treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36(2):86‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ralf Paus L, Kurzen H, Kurokawa I, et al. What causes hidradenitis suppurativa? Exp Dermatol. 2008;17(5):455‐456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(4):539‐561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yu Ca C‐W, Cook MG. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a disease of follicular epithelium, rather than apocrine glands. Br J of Dermatol. 1990;122(6):763‐769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Prens E, Deckers I. Pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5):S8‐S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sellheyer K, Krahl D. “Hidradenitis suppurativa” is acne inversa! An appeal to (finally) abandon a misnomer. Int J Dermatol. 2004;7:535‐540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laffert MV, Helmbold P, Wohlrab J, Fiedler E, Stadie V, Marsch WC. Hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa): early inflammatory events at terminal follicles and at interfollicular epidermis. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19(6):533‐537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pink A, Anzengruber F, Navarini AA. Acne and hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(3):619‐631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen W, Plewig G. Should hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa best be renamed as “dissecting terminal hair folliculitis”? Exp Dermatol. 2017;26(6):544‐547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boer J, Weltevreden EF. Hidradenitis suppurativa or acne inversa. A clinicopathological study of early lesions. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135(5):721‐725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Danby FW, Jemec GB, Marsch WC, Von Laffert M. Preliminary findings suggest hidradenitis suppurativa may be due to defective follicular support. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(5):1034‐1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fismen S, Ingvarsson G, Moseng D, et al. A clinical‐pathological review of hidradenitis suppurativa: using immunohistochemistry one disease becomes two. Apmis. 2012;120(6):433‐440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jemec GB, Hansen U. Histology of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(6):994‐999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jemec GB, Thomsen BM, Hansen U. The homogeneity of hidradenitis suppurativa lesions: a histological study of intra‐individual variation. APMIS. 1997;105(1–6):378‐383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kamp S, Fiehn AM, Stenderup K, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a disease of the absent sebaceous gland? Sebaceous gland number and volume are significantly reduced in uninvolved hair follicles from patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(5):1017‐1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kurokawa I, Nishijima S, Kusumoto K, Senzaki H, Shikata N, Tsubura A. Immunohistochemical study of cytokeratins in hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa). Int J Med Res. 2002;30(2):131‐136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kurzen H, Jung EG, Hartschuh W, Moll I, Franke WW, Moll R. Forms of epithelial differentiation of draining sinus in acne inversa (hidradenitis suppurativa). Br J Dermatol. 1999;141(2):231‐239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lafferty MV, Helmbold P, Wohlrab J, Fiedler E, Stadie V, Marsch WC. Hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa): early inflammatory events at terminal follicles and at interfollicular epidermis. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19(6):533‐537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saunte DM, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(20):2019‐2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van der Zee HH, De Ruiter L, Boer J, et al. Alterations in leucocyte subsets and histomorphology in normal‐appearing perilesional skin and early and chronic hidradenitis suppurativa lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(1):98‐106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van der Zee HH, Laman JD, Boer J, Prens EP. Hidradenitis suppurativa: viewpoint on clinical phenotyping, pathogenesis and novel treatments. Exp Dermatol. 2012;21(10):735‐739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. von Laffert M, Stadie V, Wohlrab J, Marsch WC. Hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: bilocated epithelial hyperplasia with very different sequelae. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(2):367‐371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vossen AR, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Hidradenitis Suppurativa: a systematic review integrating inflammatory pathways into a cohesive pathogenic model. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kurokawa I, Jemec GB, et al. What causes hidradenitis suppurativa? Viewpoint 4. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17(5):462‐465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith MK, Nicholson CL, Parks‐Miller A, Hamzavi IH. Hidradenitis suppurativa: an update on connecting the tracts. F1000Res. 2017;6:1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boer J, Jemec GB. Mechanical stress and the development of pseudo‐comedones and tunnels in Hidradenitis suppurativa/Acne inversa. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25(5):396‐397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ring HC, Sigsgaard V, Thorsen J, et al. The microbiome of tunnels in hidradenitis suppurativa patients. J Euro Acad Dermatol and Venereol. 2019;33(9):1775‐1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gniadecki R, Jemec GB. Lipid raft‐enriched stem cell‐like keratinocytes in the epidermis, hair follicles and sinus tracts in hidradenitis suppurativa. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13(6):361‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Frew JW, Navrazhina K, Marohn M, Lu CP, Krueger JG. Contribution of fibroblasts to tunnel formation and inflammation in hidradenitis suppurativa/Acne Inversa. Exp Dermatol. 2019;28(8):1‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Freysz M, Jemec GB, Lipsker D. A systematic review of terms used to describe hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(5):1298‐1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Otberg N, Richter H, Schaefer H, Blume‐Peytavi U, Sterry W, Lademann J. Variations of hair follicle size and distribution in different body sites. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122(1):14‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vogt A, Hadam S, Heiderhoff M, et al. Morphometry of human terminal and vellus hair follicles. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16(11):946‐950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lu C, Fuchs E. Sweat gland progenitors in development, homeostasis, and wound repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Med. 2014;4(2):a015222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Poli F, Wolkenstein P, Revuz J. Back and face involvement in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2010;221(2):137‐141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Frew JW, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. A systematic review and critical evaluation of immunohistochemical associations in hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000 Res. 2018;7:1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Plewig G, Kligman AM. The Anatomy of Follicles. Acne and Rosacea. Berlin, Heidelberg: (Eds:Plewig G, Kligman AM) : Springer; 2000:30‐49. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Panteleyev AA. Functional anatomy of the hair follicle: the secondary hair germ. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(7):701‐720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schneider MR, Paus R. Deciphering the functions of the hair follicle infundibulum in skin physiology and disease. Cell Tis Res. 2014;358(3):697‐704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Amoh Y, Kanoh M, Niiyama S, et al. Human and mouse hair follicles contain both multipotent and monopotent stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(1):176‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yang L, Zhang S, Wang G. Keratin 17 in disease pathogenesis: from cancer to dermatoses. J Pathol. 2019;247(2):158‐165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Commo S, Gaillard O, Bernard BA. The human hair follicle contains two distinct K19 positive compartments in the outer root sheath: a unifying hypothesis for stem cell reservoir? Differentiation. 2000;66(4–5):157‐164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kanoh M, Amoh Y, Sato Y, Katsuoka K. Expression of the hair stem cell‐specific marker nestin in epidermal and follicular tumors. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18(5):518‐523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li L, Mignone J, Yang M, et al. Nestin expression in hair follicle sheath progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100(17):9958‐9961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bose A, Teh MT, Mackenzie I, Waseem A. Keratin K15 as a biomarker of epidermal stem cells. Inter J Mol Sci. 2013;14(10):19385‐19398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Melnik BC, Plewig G. Impaired Notch‐MKP‐1 signalling in hidradenitis suppurativa: an approach to pathogenesis by evidence from translational biology. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22(3):172‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Welch DR, Hurst DR. Beyond the primary tumor: progression, invasion, and metastasis. In: The Molecular Basis of Human Cancer. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2017:203‐216. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Maru GB, Gandhi K, Ramchandani A, Kumar G. The role of inflammation in skin cancer. In: Inflammation and Cancer. Basel, Switzerland: Springer; 2014:437‐469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Selmer J, Skov T, Spelman L, Weedon D. Squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthomas are biologically distinct and can be diagnosed by light microscopy: a review. Histopathology. 2016;69(4):535‐541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ackerman AB. Differentiation of benign from malignant neoplasms by silhouette. Am J Dermatopath. 1989;11(4):297‐300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zouboulis CC, Desai N, Emtestam L, et al. European S1 guideline for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. J Euro Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(4):619‐644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Burney RE. 35‐year experience with surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. World J Surg. 2017;41(11):2723‐2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kohorst JJ, Baum CL, Otley CC, et al. Surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa: outcomes of 590 consecutive patients. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(9):1030‐1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lavogiez C, Delaporte E, Darras‐Vercambre S, et al. Clinicopathological study of 13 cases of squamous cell carcinoma complicating hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2010;220(2):147‐153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lee CN, Chen W, Hsu CK, Weng TT, Lee JY, Yang CC. Dissecting folliculitis (dissecting cellulitis) of the scalp: a 66‐patient case series and proposal of classification. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16(10):1219‐1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Badaoui A, Reygagne P, Cavelier‐Balloy B, et al. Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp: a retrospective study of 51 patients and review of literature. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(2):421‐423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brănişteanu DE, Molodoi A, Ciobanu D, et al. The importance of histopathologic aspects in the diagnosis of dissecting cellulitis of the scalp. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2009;50(4):719‐724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chen WT, Chi CC. Association of hidradenitis suppurativa with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(9):1022‐1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Deckers IE, Benhadou F, Koldijk MJ, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from a multicenter cross‐sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(1):49‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jørgensen AH, Thomsen SF, Karmisholt KE, Ring HC. Clinical, microbiological, immunological and imaging characteristics of tunnels and fistulas in hidradenitis suppurativa and Crohn’s disease. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29(2):118‐123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tozer PJ, Lung P, Lobo AJ, et al. Pathogenesis of Crohn's perianal fistula—understanding factors impacting on success and failure of treatment strategies. Aliment Pharm Ther. 2018;48(3):260‐269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Frew JW, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. A systematic review and critical evaluation of inflammatory cytokine associations in hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000 Res. 2018;7:1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schlapbach C, Hänni T, Yawalkar N, Hunger RE. Expression of the IL‐23/Th17 pathway in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(4):790‐798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lima AL, Karl I, Giner T, et al. Keratinocytes and neutrophils are important sources of proinflammatory molecules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(3):514‐521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Burgess DJ. Spatial transcriptomics coming of age. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20(6):317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Saha S, Matthews DA, Bessant C. High throughput discovery of protein variants using proteomics informed by transcriptomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(10):4893‐4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Theut Riis P, Thorlacius LR, Jemec GB. Investigational drugs in clinical trials for hidradenitis suppurativa. Expert Opin Investig Drug. 2018;27(1):43‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(5):422‐434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Table S1. Demographics and clinical data (where available) from the 58 subjects used in this study.

Table S2. Summary of the histochemical stains used in this study.

Figure S1. Gross photograph demonstrating the trimming technique used to examine all regions from a formalin‐fixed excisional sample of AI.

Figure S2. Early AI lesions. A. AI arises from the infundibula of the outer sheath as comedones surrounded by a hyperplastic epithelium. Inflammation is minimal (inset). B. As lesions evolve, cyst expands beyond infundibular boundaries (i.e., below the sebaceous gland duct). H&E stain, magnification: A = 5.1x (inset, 19.1x); B = 1.9x.

Figure S3. One hundred consecutive 5 μm sections were made from the lesion in Fig. 2B. A= Section 1, B= Section 37, C= Section 54, D = Section 90. What initially appears as a single cyst forms smaller, interconnected, smaller, cystic structures. There is a small, focally intense region of inflammation suggesting a future breach in the cyst wall (arrows). H&E stain, magnification, 1.4x.

Figure S4. Sections from several examples of AI demonstrating the depth to which lesions can extend. A. Infundibulum is the same depicted in Fig. 2B and C represent Hurley stage III disease. Asterisks represent the lumens of “tunnels” that are minimally lined by epithelium. The dotted line across figures measures 7 mm, the depth of a standard biopsy punch. In both C and D, the dermal lesions are lateral to their epidermal openings demonstrating the difficulty in defining dermal lesions by clinical examination of the skin surface. D1 represents a vellus hair from which the lesion arose. All figures (except D1) taken at the same magnification. H&E stain, Figures A‐D, magnification 0.5x, Figure D1, magnification 8x.

Figure S5. Demonstration of differential staining of intermediate filaments in AI. Row 1 defines changes in an early AI as defined by staining above the sebaceous gland duct. Row 2 is a low power view of intermediate filament expression across a fully developed (Hurley stage III) lesion. Row 3 defines expression of deep AI epithelium. K5 serves as a marker for epithelium throughout. K10 defines cornifying epithelium (normally there is no K10 expression below infundibulum), Staining for K15 is variable and may be expressed above and below the sebaceous duct. K17 is a proliferation marker and defines the proliferative features of AI. K19 and nestin can be considered stem cell markers that normally are expressed in the outer sheath epithelium below the infundibulum. H&E and IHC with fast red chromogen, hematoxylin counterstain, magnification Row 1=5x, Row 2=0.5x, Row 3=3.2x.

Figure S6. Ki67 immunohistochemistry of an infiltrating region of AI. There is diffuse expression primarily along the basal cell layer; however, the leading edge of a tendril (arrowhead) does not express greater proliferative activity than the lateral boundaries. IHC with fast red chromogen, hematoxylin counterstain, magnification 7.3x.

Figure S7. Two examples of changes consistent with Hurley stage I lesions. The inflammation is in the mid dermis and centered around a ruptured cyst with a cyst wall that is only partially intact (insets). The arrows in both figures are pointing to the remnants of the cyst wall. H&E stain, magnification A and B = 0.5x, Insets A1 = 3.3x, B1 = 2.9x.

Figure S8. Example of a deep region of Hurley stage III disease. There are numerous intersecting tunnels (asterisks). A. K5 staining demonstrates that there is a loss of epithelium lining these tracts. B and C. K10 staining demonstrate shards of keratin associated with these tunnels consistent with a ruptured cyst or necrosis of a cornifying tendril. A = H&E stain; B = immunostaining for K5, C and D, immunostaining for K10, all using fast red chromogen, hematoxylin counter stain, magnification A, B, C = 1.6x, D = 2.4x.

Figure S9. Early breach of cyst wall in the deep dermis of Hurley stage III disease. A and B. There is a migration of neutrophils through the cyst wall into the lumen containing cornified debris. Associated with the cornified debris are Gram + coccoid and coccobacillary bacteria (short arrows) that may be recognized by communication of keratinocytes/epidermal antigen processing cells. A and B, H&E stain; C, Grams stain, magnification A = 3.4x, B =15.2x, C = 40x.

Figure S10. Heterogeneous infiltration of inflammatory cells in an area of active inflammation in AI. The reaction contains abundant macrophages, dendritic cells, T‐cells, Bcells (including plasma cell) components. Neutrophils are not wellrepresented in this region although other areas contain abscesses composed primarily of MPO+ cell. The distribution of mast cells (c‐Kit) is representative where their numbers appear relative to inflammatory intensity and they are not present as a predominant inflammatory cell population. Eosinophils (asterisks) vary from sample to sample and in most samples were much less common than mast cells. H&E and expression defined by IHC identified by labels. IHC images: fast red chromogen and hematoxylin, magnification, H&E stain upper left, 0.9x, H&E stain lower right, 82.3x, all other figures, 10X.

Figure S11. Difference in inflammatory intensity and composition in a region of the superficial dermis over an active AI lesion compared to a deeper, more active inflamed area adjacent to an inflamed cyst (compare with Sup Fig 10). Monocytes/macrophages and CD4+ T‐cells are abundant but in comparison, CD8 cells, B‐cells (including plasma cells), CD11c+ dendritic cells, and neutrophils are underrepresented. Mast cells correspond with inflammatory intensity. Note that CD138 is expressed in basal/suprabasal keratinocytes and c‐Kit is expressed in melanocytes. Histochemical and IHC immunopositivity identified by labels. IHC images: fast red chromogen and hematoxylin, magnification, H&E stain upper left, 0.9x, all other figures, 10x.