Abstract

There is a great demand for accurate non‐invasive measures to better define the natural history of disease progression or treatment outcome in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and to facilitate the inclusion of a large range of participants in DMD clinical trials. This review aims to investigate which MRI sequences and analysis methods have been used and to identify future needs. Medline, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, Inspec, and Compendex databases were searched up to 2 November 2019, using keywords “magnetic resonance imaging” and “Duchenne muscular dystrophy.” The review showed the trend of using T1w and T2w MRI images for semi‐qualitative inspection of structural alterations of DMD muscle using a diversity of grading scales, with increasing use of T2map, Dixon, and MR spectroscopy (MRS). High‐field (>3T) MRI dominated the studies with animal models. The quantitative MRI techniques have allowed a more precise estimation of local or generalized disease severity. Longitudinal studies assessing the effect of an intervention have also become more prominent, in both clinical and animal model subjects. Quality assessment of the included longitudinal studies was performed using the Newcastle‐Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale adapted to comprise bias in selection, comparability, exposure, and outcome. Additional large clinical trials are needed to consolidate research using MRI as a biomarker in DMD and to validate findings against established gold standards. This future work should use a multiparametric and quantitative MRI acquisition protocol, assess the repeatability of measurements, and correlate findings to histologic parameters.

Keywords: DMD, GRMD, imaging biomarkers, MDX, MRI, systematic literature review

Abbreviations

- AFF

apparent fat fraction

- CK

creatine kinase

- CT

computed tomography

- DCE

dynamic contrast‐enhanced

- DMD

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- DWI

diffusion‐weighted imaging

- FOS

first‐order statistics

- FOV

field‐of‐view

- FR

fraction

- GTSDM

gray‐tone spatial‐dependence matrix

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- LBP

local binary pattern

- mf‐CSA

muscle fiber cross‐sectional area

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- NGTDM

neighborhood gray‐tone difference matrix

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NMRS

nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- NOS

Newcastle‐Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale

- PD

proton density

- PET

positron emission tomography

- qMRI

quantitative MRI

- RLM

run‐length matrix

- ROI

region of interest

- SNR

signal‐to‐noise ratio

- T1w

T1 weighted

- T2w

T2 weighted

- TE

echo time

- TM

texture method

- TR

repetition time

- UHF

ultrahigh field

- US

ultrasound

- V/CSA

volume/cross‐sectional area

- VHF

very high field

1. INTRODUCTION

Although no treatment currently can prevent or reverse the effects of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), several pharmacologic, cellular, and genetic approaches may reduce disease effects and improve the quality of life for DMD patients. 1 In assessing the outcomes of clinical trials of these treatments, objective biomarkers must be developed and assessed longitudinally in natural history studies. 2 Ideally, these biomarkers should be compared against results from the histological analysis of muscle biopsies, which has historically been used as the gold standard for disease assessment. However, due to the inherent invasive character of biopsy, non‐invasive methods to extract information corresponding to biological characteristics of DMD muscle are in great demand.

Several non‐invasive imaging modalities have the potential to provide objective insight on DMD disease progression: for example computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), ultrasound (US), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). 3 , 4 While CT can be used to detect structural changes in muscle tissue such as fat deposition, 5 its use in DMD is limited by potential side effects of X‐ray exposure and insensitivity for differentiation between adipose and connective tissue, especially in younger patients. 6 The use of PET allows identification of reduced metabolism due to replacement of muscle with connective tissue or fat in DMD but this could be obscured by increased uptake of brown fat. 3 Evidence of increased muscle echogenicity is seen early on US in DMD, providing a potential imaging tool to track disease progression. 7

Due to its high soft‐tissue contrast, high resolution, and absence of ionizing radiation, MRI has emerged as a promising non‐invasive method for imaging skeletal muscles. 8 Various MRI sequences have been widely used to monitor DMD disease qualitatively 9 , 10 and quantitatively, 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 with a general hypothesis that structural changes in muscle will be reflected in MRI images. Qualitative analysis allows subjective grading of disease features, such as the level of signal intensity on T1 weighted (T1w) and T2 weighted (T2w) MRI protocols. Advances in quantitative MRI (qMRI) sequences (ie, T1map, T2map, diffusion‐weighted imaging [DWI], and Dixon) have provided promising results in objectively monitoring DMD patients longitudinally. 15 Nonetheless, with no consensus on particular imaging sequences or analysis methods and tools to be used, the use of MRI as a DMD biomarker remains underappreciated.

Accordingly, this study aimed to investigate different MRI sequences that have been used for diagnosis and quantification of disease severity in DMD skeletal muscle, to answer two fundamental questions: (a) What are the MRI sequences that have been used to assess changes in skeletal muscle in DMD and pre‐clinical models of DMD? (b) What are the methods that have been used to analyze specific MRI sequences in order to differentiate healthy and diseased muscles, assess therapeutic response, or differentiate different stages of DMD?

2. METHODS

2.1. Data sources and search method

This review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta‐Analyses) guidelines, 16 with details summarized in Supporting Information Material S1, which is available online. A systematic search was conducted of the databases of Medline, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, and Engineering Village with the aid of an experienced librarian on 2 November 2019. The following terms were used for the searches: “magnetic resonance imaging” and “Duchenne muscular dystrophy”. The results from all five searches were combined using EndNote and automatically verified to ensure the exclusion of articles that had the same title or were written by the same authors and/or published in the same journal. The remaining articles were considered for study selection.

2.2. Study selection

Two authors (L.A. and J.F.G.) independently reviewed the journal and paper titles and abstracts. The selected papers then underwent full‐text screening and eventually were reviewed to include relevant information. Any discrepancies regarding study inclusion or during the subsequent review process were resolved by full‐text screening and discussion. All papers with any of the components missing were passed directly to the full‐text screening.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included only clinical or preclinical studies reporting MRI of skeletal muscles with the following aims: characterization of differences between healthy and DMD muscle; characterization of the natural history of DMD disease progression; correlations between muscle MRI and current standard of care diagnostic methods (blood biochemistry, molecular assessment, clinical assessment, functional assessment, or histology); assessment of the effect of an intervention (medication, supplements, contrast medium, exercise, muscle stimulation, injury). No restrictions were made based on location, size of field of view (FOV), or the number of skeletal muscles imaged.

Only studies written in English were included in this review. Prior to the review, a decision was made to exclude any study with too few participating subjects: <7 for patient studies and <3 for animal studies. Therefore, all individual case reports and studies with no information on the number of subjects were excluded. In addition, all the following types of studies were excluded: (a) papers describing non‐original research (editorials, commentaries, letters, reviews, meta‐analyses, opinions, family descriptions, conference summaries, conference abstracts, registries, study protocols, technical notes, pictorial essays), (b) papers not based on in vivo subjects (histology, phantom, ex vivo, synthetic data), (c) papers reporting animal models other than murine (MDX) or canine (golden retriever muscular dystrophy, GRMD), (d) papers reporting imaging of non‐skeletal muscles, and (e) papers not differentiating between different dystrophy types.

2.4. Data extraction

A data form was designed to extract the following information: DMD affected or carrier, species (human, murine, canine), population (number of DMD, number of DMD‐control, number of healthy‐treated, number of healthy‐control), MRI field strength (midfield [≤1T], high field [>1T and ≤3T], very high field [>3T and ≤7T], and ultra‐high‐field [>7T]), MRI sequence, use of MRI contrast agent, the number of muscles or compartments analyzed, gold standard used (none, histology, molecular assessment, functional ability, clinical assessment, biochemistry), the aim of the study (differentiation, natural history, the effect of the intervention, clinical trial), study design (cross‐sectional, longitudinal), type of data analysis, and type of performance analysis. All selected papers were independently reviewed by two reviewers, and data extraction was cross‐checked by a third reviewer (A.E.). Disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by consensus and arbitrage by another author (J.N.K). The following data were extracted from the full papers: year of publication, human or animal study, type of animal model used, type of study (cross‐sectional or longitudinal), number of subjects, number of muscles imaged, MRI sequence(s) used, contrast agent used, image analysis method. All papers were divided into the following categories: (a) cross‐sectional studies to differentiate healthy and diseased muscle or to grade disease severity, (b) cross‐sectional studies to correlate the imaging results to the current standard of care diagnostics, and (c) longitudinal measurements to characterize the natural history of disease progression or assess changes due to intervention.

2.5. Data synthesis and analysis

The following MRI sequences were identified: T1w, T2w, T1‐mapping, T2‐mapping, proton density (PD), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), Dixon, and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). MRS was differentiated according to the element used: 1H, 31P, 23Na. No further subdivision was made regarding the type of imaging protocol, use of contrast agent, or fat suppression mechanisms (including short tau inversion recovery).

T1w MRI sequences use spin‐lattice relaxation by using a short repetition time (TR) and a short echo time (TE), while T2w MRI sequences assess spin‐spin relaxation by using a long TR and a long TE. PD‐weighted MRI created by a long TR (reduce T1) and a short TE (minimize T2) to reflect the actual density of protons. 17 PD‐weighted MRI sequences share some features of both T1w and T2w MRI. T1‐mapping, also referred to as native T1‐mapping, measures pixel‐wise T1 relaxation time or spin‐lattice or longitudinal relaxation time, the decay constant for the recovery of the z‐component of the nuclear spin magnetization towards its thermal equilibrium value. T1‐mapping traditionally uses a series of independent single‐point T1w measurements at different inversion times. As this acquisition method is rather time‐consuming, several MRI sequences were developed to speed up the acquisition, eg, inversion recovery spin echo, echo planar imaging, inversion recovery spoiled gradient echo, and variable flip angle. 18 T2‐mapping measures pixel‐wise T2 relaxation time or spin‐spin or transverse relaxation time, which represents the time constant that the transverse components of magnetization decay or diphase toward their thermal equilibrium value. T2map is typically reconstructed from a series of T2w images at various TE. 19

DTI is an MRI technique that assesses restricted (anisotropic) water diffusion using bi‐polar preparation gradients. It is often visualized using pseudo‐colors and can be used to produce fiber tract images. Additionally, DTI provides structural information about muscle. 20 The Dixon technique is an MRI method for fat suppression and/or fat quantification that uses a simple spectroscopic imaging technique for water and fat separation. 21 , 22 The technique acquires two separate images with a modified spin‐echo pulse sequence with water and fat signals in‐phase and 180° out‐of‐phase. Each voxel in MRS produces a set of signals called the magnetic resonance spectrum, defined by two axes: signal intensity and signal position (chemical shift). Biomedical applications are mainly focused on imaging of protons (1H), phosphorus (21P), and carbon (13C).

Image analysis methods to assess muscle quality were divided into five categories: semi‐qualitative scoring (QS), first‐order statistics (FOS), volume/cross‐sectional area (V/CSA), fractions (FR), and texture methods (TM).

2.5.1. QS

The semi‐qualitative assessment of DMD imaged by MRI is usually graded by two or more independent observers using several ordinal scales with gradually increasing muscle involvement. Often, for purposes of anatomical clarity and synergistic function, muscles have been graded together as a muscle group. These methods provide an overall impression of the degree of increased signal intensity in T1w and/or T2w MRI:

Grading of fat infiltration using T1w MRI without fat suppression: (a) severity of fat infiltration and subcutaneous fat using a three‐point scale (0, absent; 1, mild; 2, severe) 23 ; (b) several muscles with fatty infiltration using a three‐point scale with four distinguished grades ranging from 0 to 3 23 ; (c) grading fatty infiltration using a four‐point grading system, consisting of four different stages (1, normal; 2, patchy intramuscular signal; 3, markedly hyperintense; 4, homogeneous hyperintense signal in whole muscle) proposed by Olsen et al 24 ; (d) grading fatty infiltration using a four‐point grading system, consisting of six different stages (0‐1‐2a‐2b‐3‐4) ordered an increasing percentage of fat in the images 25 ; and (e) modified Mercuri scale using a four‐point grading scale, consisting of six different stages (0, normal muscle; 2, mild infiltration, less than 30% of the muscle was infiltrated; 3, moderate infiltration with 30%‐60% infiltrated muscle; 4, severe infiltration with more than 60% infiltrated muscle. 6

Grading of edema patterns using T2w MRI (without fat suppression) originally proposed by Borsato 26 and modified by Kim et al27 uses a four‐point grading system on a scale from 0 to 3 (0, no; 1, minimal interfascicular edema; 2, minimal inter‐ and intrafascicular edema; 3, moderate inter‐ and intrafascicular edema).

Four‐point grading system by using patterns in T1w spin‐echo (SE) and short‐tau inversion sequence to grade edema, and T1w MRI to grade fat infiltration 27 with 1, normal signal on both T1w MRI (with and without fat suppression); 2, edema on T1w MRI without fat suppression, no fatty infiltration on fat‐suppressed T1w MRI; 3, edema on T1w MRI without fat suppression and minimal‐moderate fatty infiltration fat‐suppressed T1w MRI; 4, normal signal on both T1w MRI (with fat suppression), and large fatty infiltration on fat‐suppressed T1w MRI.

2.5.2. FOS

These methods characterize muscle by non‐spatial descriptors, that is, the gray‐level frequency distributions as mean, median, SD, skewness, maximum, minimum, and range.

2.5.3. V/CSA

Under the assumption that structural and compositional changes in skeletal muscle affected by DMD alter cross‐sectional area (and consequently also the muscle volume), some studies characterize muscle by V/CSA. The methods for V/CSA assessment vary from completely manual annotations to automatic segmentation protocols.

2.5.4. FR

The muscle composition is assessed with intramuscular fat fraction using 1H‐MRS 28 or chemical shift‐based imaging techniques 29 by the integration of the phase‐corrected spectra from the lipid and 1H2O parts of the spectrum. Additionally, two‐point Dixon 21 or three‐point Dixon 22 methods acquire images at identical positions with water and fat protons in‐phase and opposed‐phase, respectively. The intramuscular fat fraction, also referred to as (relative) fat content map, is generated from the pixel‐wise fat and water fraction.

2.5.5. TM

Texture‐based methods extract the local spatial image intensity distribution. This category includes gray‐tone spatial‐dependence matrix (GTSDM), 30 neighborhood gray‐tone difference matrix (NGTDM), 31 run‐length matrix (RLM), 32 and local binary pattern (LBP). 33

2.6. Risk of bias assessment

Conclusions reached through systematic reviews are influenced by the quality of the papers included, largely related to various sources of potential bias. 34 In an effort to minimize selection bias, we performed an initial wide search without limitations and conducted the review according to PRISMA guidelines. 16 Given the heterogeneous nature of this review, for instance, including both human and animal studies and a range of study designs, we did not systematically assess the potential for bias across all 127 papers. Since the recommendations generated by this review are most important for patient care, we assessed longitudinal DMD studies reporting clinical data. The included papers were subjected to rigorous appraisal by two authors (L.A. and A.E.) using the extended Newcastle‐Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) 35 , 36 adapted to include assessment of outcome, the validity of follow‐up, and dropout rate. This assessment awards points across four domains to a total of 10 points: selection (4), comparability (1), exposure (3), and outcome (2). Based on the score, the datasets were categorized as high (score ≥9), moderate (6 ≤ scores ≤8), or low (scores ≤5). Disagreements were arbitrated by a third author (J.F.G.).

3. RESULTS

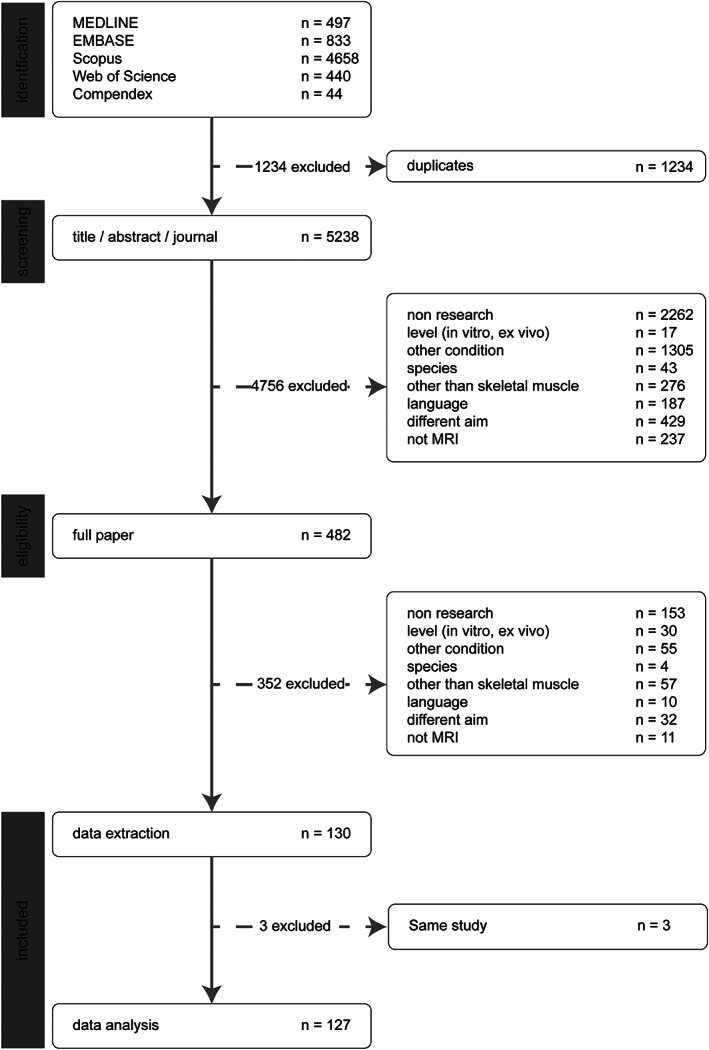

Figure 1 presents details on literature inclusion after reviewing the paper title, the journal‐title, abstract, and full paper. In summary, of the 5238 potentially relevant articles, 482 (9.2%) were considered for inclusion. After a full‐text screening for all relevant papers, an additional 352 were excluded. At this stage, three additional papers were excluded as they reported the results on the same dataset as that used in another paper included. For these publications, the most recent one was included in the analysis. Therefore, the data from 127 original papers 6 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 15 , 23 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 , 123 , 124 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 , 129 , 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 , 134 , 135 , 136 , 137 , 138 , 139 , 140 , 141 , 142 , 143 , 144 , 145 , 146 , 147 , 148 , 149 , 150 , 151 , 152 , 153 were extracted for further analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Results of the literature search. PRISMA flow diagram for study collection, 16 showing the number of studies identified, screened, eligible, and included in the systematic review

3.1. General characteristics

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of all 127 selected papers. A paper may have included more than one MRI sequence or aim, and included different protocols including a variety of subjects, or more than one MRI device. On average, the studies included 31.1 (4‐171) subjects, with 24.5 (0‐66) diseased and impacted by intervention, 17.8 (0‐171) diseased without intervention, 1 (0‐41) healthy treated, and 7.6 (0‐70) healthy untreated. Two studies (1.6%) reported five different MRI sequences, 14 studies (11%) reported four different sequences, 25 studies (20%) reported three sequences, 33 studies (26%) reported two sequences, and 54 studies (43%) reported one sequence. Moreover, eight studies 48 , 57 , 78 , 88 , 109 , 117 , 120 , 122 used a contrast agent, and two also reported the use of dynamic contrast‐enhanced (DCE) MRI. 120 , 122 From 42 studies assessing MRS, 28 , 29 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 44 , 45 , 50 , 52 , 58 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 66 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 72 , 74 , 76 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 87 , 89 , 99 , 103 , 110 , 111 , 116 , 123 , 128 , 129 , 133 , 134 , 135 , 136 , 138 , 139 , 146 , 150 16 reported solely MRS without any additional MRI sequence. A total of 13 studies used two different nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) elements, adding either 31P or 23Na to 1H. Additionally, 17 studies reported only 1H and 12 studies only 31P‐NMR spectroscopy. DTI was used in 10 studies. 15 , 65 , 100 , 104 , 105 , 107 , 108 , 125 , 140 , 145 The studies included MRI field strengths ranging from midfield to ultra‐high field. The majority of studies were cross‐sectional. A variety of methods were used to analyze the MRI data in decreasing order: FOS, followed by FR, V/CSA, SQ, raw MRI data, and TX.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the included papers (n = 127) detailing MRI sequences and magnetic field, subjects used, and study type

| Characteristic | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRI sequence method | PD | 4 | 3% |

| T1w | 54 | 46% | |

| T2w | 38 | 40% | |

| T1 map | 5 | 5% | |

| T2 map | 45 | 40% | |

| Dixon | 24 | 19% | |

| DTI | 10 | 8% | |

| NMR spectroscopy | 43 | 33% | |

| Subject | Human | 80 | 63% |

| Murine model | 30 | 24% | |

| Canine model | 17 | 13% | |

| MRI field | Midfield MRI (MF‐MRI) || field >1T | 5 | 4% |

| High field MRI (HF‐MRI) || 1T ≤ field <3T | 33 | 26% | |

| Very‐high field MRI (VHF‐MRI) || 3T ≤ field <7T | 79 | 62% | |

| Ultra‐high field MRI (UHF‐MRI) || field ≥7T | 17 | 13% | |

| Study type | Cross‐sectional | 81 | 64% |

| Longitudinal | 50 | 39% | |

| Analysis type | Raw MRI data | 16 | 13% |

| FOS | 61 | 48% | |

| TM | 13 | 10% | |

| V/CSA | 22 | 17% | |

| FR | 35 | 28% | |

| SQ | 17 | 13% |

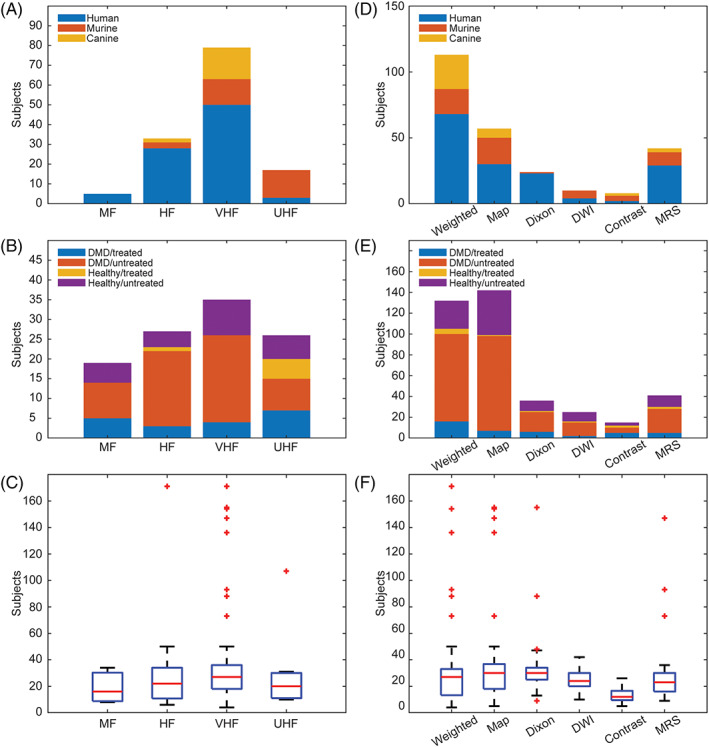

The number of imaging studies assessing DMD is increasing steadily, that is, from 13 studies published up to 1994 to 54 papers in the period 2014‐2019 (see Figure 2A). In the latest 5 y (2014‐2019), 65% of papers reported clinical studies, while 24% were murine and 11% were canine. Figure 2B illustrates the composition of subjects used, with a clear trend of increasing numbers, especially in clinical studies. Recent pre‐clinical studies have tended to include vehicle‐treated control animals. Figure 2C shows the distribution of studies according to the MRI sequence used. Generally, the contribution of T1w images has been historically high. However, T2map, DWI, and Dixon sequences have gained interest in the latest 10 y. Dixon maps have increasingly been used since their introduction in 1984. 21 In the most recent 5 y (2014‐2019), the most‐used MRI sequences included: weighted images (40%) and MRI maps (24%), followed by Dixon (16%), MRS (12%), and DTI (7%). Until 2009, the contribution of studies using a longitudinal design was relatively low but stable (Figure 2D). In the most recent 10 y, longitudinal studies have gained interest, reaching 38% in the latest 5 years (2014‐2019). These longitudinal studies have mainly assessed the natural history of disease progression or the effect of the intervention, that is, medication, food supplements, contrast agent, exercise, muscle stimulation, injury.

FIGURE 2.

The number of papers differentiating studies based on the type of subjects: human, murine, canine (A), study population: diseased with intervention, diseased without intervention, healthy with intervention, healthy without intervention (B), MRI sequence (C), and cross‐sectional vs. longitudinal (D)

Figure 3 identifies studies according to MRI field strength (left column) and MRI sequence (right column). Considering the use of MRI field strength in DMD research, there has been a clear tendency to increase strength over the years. In particular, murine models have been extensively imaged using ultra‐high field MRI (UHF‐MRI). Generally, weighted and mapping sequences have mainly been used in MRI sequences. On average, each study analyzed five (1‐44) muscles with clinical studies analyzing more muscle (5.6), versus murine (1.9) and canine (4) studies. Out of 127 included studies, 37% analyzed only one muscle or compartment, while 10.2% 6 , 10 , 27 , 37 , 38 , 47 , 59 , 78 , 86 , 107 , 112 , 143 , 148 analyzed 10 or more different muscles for each subject. Typically, studies using very high field MRI (VHF‐MRI) or T1w and Dixon sequences analyzed more muscles.

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of studies (subject type, population, and number of muscles assessed) by different field strengths (A‐C) and different MRI sequences (D‐F). HF, high field strength; MF, medium field strength; T1w, T1‐weighted; T2w, T2‐weighted; T1m, T1‐mapping; T2m, T2‐mapping

3.2. Papers reporting correlation experiments

Of 127 papers included in this review, 29 (23%) correlated the current standard of care for assessment of DMD (eg, clinical functional grading or functional ability) with the semi‐quantitative MRI assessment, 10 , 37 , 47 or quantitative MRI assessment. 6 , 11 , 38 , 39 , 44 , 54 , 56 , 59 , 63 , 73 , 76 , 79 , 88 , 89 , 113 , 122 , 123 , 126 , 137 , 138 , 143 , 144 , 145 , 153 These papers reported a statistically significant correlation between fatty infiltration of muscle on MRI and functional status. 10 , 37 , 47

Only five papers correlated histologic findings with either semi‐qualitative or quantitative assessment 8 , 77 , 94 , 105 , 108 of MRI. In the Kinali et al. paper, 77 histology and MRI images were scored separately by two independent observers each, pathologists using hematoxylin‐eosin (H&E) ‐stained sections and radiologists using MRI images. The reported coefficient of correlation was 0.81 when describing the association between histology and MRI scores based upon a T1w sequence. Fan et al. 8 used histologic images (H&E, acidic and basic ATPase, and trichrome) for semi‐automatic assessment of the size of type 1 and 2 fibers, percent area of connective tissue, and the number of necrotic and regenerated fibers. These parameters were then correlated with texture and FOS features assessed from T1w and T2map MRI. The paper presented only the P‐values associated with student T‐test ranging (0.02‐0.97), without r‐values. Mathur et al. 94 measured the percentage of Evans blue dye positive area in MDX and control mice after running exercise and correlated it with the percentage of pixels with elevated T2 relaxation time on T2map with a correlation coefficient of 0.79. Qin et al. 108 found a negative correlation coefficient of −0.71 between the mechanical anisotropic ratio (assessed by anisotropic magnetic resonance elastography) and the percentage of necrotic fibers (assessed by semi‐automatic analysis of H&E and Safran ‐stained sections). In other words, skeletal muscle was shown to have elastic properties (shear storage moduli) that vary with respect to fiber orientation (anisotropy), and the degree of anisotropy (expressed as a mechanical anisotropic ratio) correlated negatively with necrosis. Park et al 105 used H&E and Massonʼs trichrome stained sections to assess muscle fiber CSA (mf‐CSA). The correlation between MRI features and mf‐CSA was consistently high (ranging 0.7‐0.8) for tibialis anterior in the MDX model and control subjects. For the gastrocnemius muscle, the correlation between MRI features and mf‐CSA was lower for control subjects (r = 0.52) compared to the MDX model (r = 0.8).

An additional five papers compared quantitative and semi‐qualitative biomarkers of MRI, 15 , 69 , 76 , 87 , 141 with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.62 to 1. These papers used different semi‐qualitative scores to grade fat fraction using T1w and/or T2w sequences. The fat fraction was correlated with different MRI features assessed by 1H‐MRS, 69 , 76 DTI, 15 or by a Dixon sequence. 87 , 141 Additionally, Ponrartana et al. 107 found a correlation between muscle strength and fat fraction (r = −0.89), fractional anisotropy (r = −0.96), and apparent diffusion coefficient (r = 0.83).

Studies have not established the optimal number of MRI slices to assess. One paper compared findings from local (one slice) and multi‐slice approaches in semi‐qualitatively assessing T1w images. 9 They concluded that caution needs to be taken when using single‐slice acquisitions, as they may not appropriately represent overall disease status. Consistent with this result, another paper found that manual segmentation of every fifth slice, with subsequent interpolation to the muscle length, more accurately predicted effects than mid‐muscle belly analysis. 8

Seven papers reported correlations between different quantitative parameters. In general, all papers used Spearmanʼs rank or Pearsonʼs correlation coefficient, but the use of these methods was not rationalized. The time of creatine rephosphorylation, reflecting mitochondrial oxidative capacity) and assessed using 31P‐NMR, 82 showed a tight correlation with perfusion parameters, ranging from 0.66 (maximum perfusion) to 0.99 (total perfusion in the first 30 s). T2w images showed a significant correlation to lipid fraction assessed using 1H‐NMR (ranging from 0.74 to 0.92, depending on the muscle assessed), 28 while pH assessed by 1H‐NMR and 31P‐NMR showed a relatively low correlation of 0.53. 111 Additionally, the fat fraction assessed by a Dixon sequence was correlated to DTI features MD & λ3, showing a weak correlation of −0.26 and −0.34 respectively, whereas λ1, λ2, and FA showed no correlation with fat fraction. 65 On the other hand, fat fraction assessed by a Dixon sequence correlated well (r = 0.94) with fat fraction assessed by 1H‐NMR. 58 Even with a such small number of publications, there were controversies. For example, the correlation between T2map and fatty infiltration assessed using 3D gradient‐echo Dixon sequences was assessed as significant (0.7) in one study 142 but not in another. 90

3.3. Papers reporting agreement data

The agreement between two graders in a semi‐qualitative study was reported in four of the included papers (3%), with reliability assessed using the Cohen kappa statistic of 0.66, 151 and ranging from 0.78 to 0.96. 73 , 76 Furthermore, test‐retest reliability was reported in eight (6.3%) papers assessing a correlation between the two tests: drawing a region of interest (ROI) 57 , 76 , 97 , 98 , 106 , 153 and cross‐sectional area. 38 One additional paper reported test‐retest reliability of the entire MRS protocol, 111 aiming to assess its reproducibility. This protocol imaged five healthy control subjects twice within a 2 h interval and observed average pH differences in magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMRS) of 0.02 and 0.01 for 1H‐NMRS and 31P‐NMRS, respectively. Several papers reported the interobserver variability with intraclass correlation coefficients comparable for intra‐observer assessment (0.80‐0.84) and interobserver assessment (0.81‐0.86), 106 with the coefficient of variations ranging from 7% for intra‐observer to 13% for interobserver assessment. 97 , 98 Considering intra‐observer variability, redrawing ROIs was shown to change the average signal intensity up to 21%, but no significant interobserver differences between the three observers were revealed. 57

In addition, Bland‐Altman methods were used to assess the agreement between the two repeated measurements, 66 so as to determine the difference between the fat fraction calculated at the central slices and fat fraction calculated over the whole muscle, 67 the degree of inter‐rater agreement, 90 or between two different analysis methods 29 , 91 , 141 or two different sequences. 87 , 110 Considering intra‐observer variability, 31P‐NMR with agreement further supported by high intra‐class correlation of 0.98 for the high signal‐to‐noise ratio (SNR) condition, 0.97 in low SNR condition. Mankodi et al. 90 demonstrated a good agreement between two independent measurements (percent muscle fat and muscle water) in the same muscle. Two different MRI acquisitions producing apparent fat fraction (AFF) showed a strong correlation (0.92), with the Bland‐Altman plot showing that 95% of the differences in the AFF were within the limits of agreement (−7.97, 9.88). 91 To evaluate the ability of chemical shift‐based MRI for quantitative assessment of fat fraction in dystrophic muscles, Triplett et al. 29 evaluated the bias in different models processing MRI data, while Wokke et al. 141 evaluated different models to map Dixon sequence into a quantitative tool to assess muscle fat fraction.

3.4. Risk of bias

Of the 127 included papers, 23 reported longitudinal DMD clinical studies: 9 were natural history, 11 , 44 , 59 , 63 , 64 , 66 , 95 , 110 , 112 1 reported the effect of exercise 74 on untreated healthy and DMD muscle, and 13 reported a treatment effect. 40 , 41 , 57 , 61 , 75 , 91 , 97 , 111 , 133 , 135 , 136 , 137 , 138 Based on the NOS, 4 studies ranked as high, 41 , 91 , 135 , 138 18 studies ranked as moderate, 11 , 44 , 57 , 59 , 61 , 63 , 64 , 66 , 74 , 75 , 95 , 97 , 110 , 112 , 133 , 136 , 137 and 1 study ranked as low 40 (Table 2). Three studies included two types of controls: non‐treated patients and age‐matched healthy subjects. 91 , 135 , 138 As illustrated in Table 2, several studies lack critical information to assess and interpret the risk of bias. For instance, in 7 of 23 included studies, the authors did not mention the ambulatory status of the patients at inclusion; 8 studies did not include information on lost subjects at the follow‐up, 2 studies had an excessive patient loss at the follow‐up, 44 , 133 and 5 studies did not mention the study length at all.

TABLE 2.

Description of the studies included

| First author | No. DMD treated/not treated | No. healthy control | Average age intervention/control year (range) | Ambulatory at inclusion, (n) | Study length (week) | Medication | Gold standard | Features extracted | Data analysis | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mankodi 91 | 6/3 | 20 | 8.8 (6‐24)/10 (5‐14) | 9 | 48 | Oligonucleotide | FA | FOS, FR | ST, CORR | 10 |

| Weber 135 | 5/6 | 16 | (5‐22)/16 | ‐ | ‐ | Glucocorticoid | FA | SQ, FOS | ST | 9 |

| Willcocks 138 | 98/11 | 38 | 8.7 (5‐12.9)/‐ | 109 | 12 | Corticosteroid | CA | FOS | ST | 9 |

| Mavrogeni 97 | 17/17 | ‐ | (17‐22)/(12‐15) | 17 | ‐ | Deflazacort | ‐ | FOS | ST | 8 |

| Banerjee 41 | 18/15 | ‐ | 7 (3‐12)/7.2 (3‐12) | 33 | 8 | Creatine monohydrate | FA | FOS | ST | 10 |

| Arpan 39 | 15/‐ | 15 | 5‐8.9/‐ | ‐ | 52 | Corticosteroid | FA | FR | ST | 5 |

| Garrood 57 | 11/‐ | 5 | 8.2 (6.6‐9.9)/7.6 (6.9‐8.7) | 11 | 1 | Corticosteroid | ‐ | FOS | ST | 7 |

| Griffiths 61 | 10/‐ | 5 | (6‐13)/(9‐14) | 15 | 24/12 | Allopurinol/ribose | Histology | FOS | ST | 8 |

| Kemp 74 | 10/‐ | 20 | (10‐17)/(20‐50) | ‐ | ‐ | Exercise | FA | FOS | ST | 6 |

| Reyngoudt 111 | 23/‐ | 14 | 10.3 (6‐15)/11.5 (8‐15) | 20 | ‐ | Corticosteroid* | ‐ | FR | CORR | 6 |

| Wary 133 | 24/‐ | 12 | (6‐18)/(7‐18) | 10 | 55 | Exon 53 skipping therapy | FA | FOS, FR | ST, CORR | 8 |

| Weber 136 | 8/‐ | 8 | 9.5 (5‐22)/9.5(5‐16) | ‐ | 31 | Corticosteroid** | FA | SQ, FOS | ST | 8 |

| Willcocks 137 | 16/− | 15 | 7.8 (5‐13)/9.7 (5‐13) | 30 | 52 | Glucocorticoid* | FA | FOS | ST | 8 |

| Kim 6 | 11/‐ | ‐ | 8.5 (5‐14)/‐ | ‐ | 81 | Corticosteroid* | CA | FOS | ST | 8 |

| Godi 59 | ‐/26 | 5 | (5.8‐12.2)/(9.4‐13) | 26 | 96 | NT | FA | FOS | ST, CORR | 8 |

| Hooijmans 66 | ‐/18 | 12 | 9.8 (5‐15.4)/10.3(5‐14) | 13 | 24 | Corticosteroid* | ‐ | V/CSA | ST | 7 |

| Matsumura 95 | ‐/20 | 15 | (1‐14)/(3‐47) | ‐ | ‐ | NT | ‐ | FR | CORR | 6 |

| Reyngoudt 110 | ‐/25 | 7 | 10.5 (6‐15)/10.8 (8‐15) | ‐ | 12 | NT | ‐ | FR, V/CSA | ST | 7 |

| Ricotti 112 | ‐/15 | 10 | 13.3 (10.8‐17.3)/14.6 (13‐17) | 0 | 12 | Corticosteroid** | FA | V/CSA | ST | 7 |

| Barnard 44 | ‐/136 | ‐ | 8.3 (4.6‐14.6) | 136 | 48 | NT | FA | FR | CORR | 6 |

| Bonati 11 | ‐/20 | ‐ | 14.9 (5‐23) | 11 | 12 | NT | CA | FOS | ST, CORR | 7 |

| Hogrel 63 | ‐/25 | ‐ | 11 (6.3‐15) | 10 | 12 | NT | CA | FOS | ST, CORR | 7 |

| Hollingsworth 64 | ‐/11 | ‐ | 8.7 (6.6‐9.9) | 8 | 81 | Corticosteroid* | ‐ | FOS | ST | 7 |

Note: Medication: *all DMD patients on medication, no baseline without medication; ** part of the DMD population on steroids, no baseline without medication; NT, no treatment, natural history study.

Gold standard: CA, clinical assessment; FA, functional ability.

Features extracted: FOS, SCA, SQ.

Data analysis: CORR, correlation; ST, statistical testing.

NOS (extended): high (score ≥9); moderate (6≤ scores ≤8); low (scores ≤5).

4. DISCUSSION

For biomarkers to be widely used in clinical trials, protocols and data analysis must be consistent across centers and, ideally, correlate with gold standard indices. Upon reviewing data from this systematic review, consistency has not yet been achieved in the use of MRI in DMD. Given the wide range of MRI sequences, analysis methods, and combinations used, it was not possible to compare results between studies or pool data into a meta‐analysis. With that said, based on our study, there has been a trend to use T1w and T2w MRI images for semi‐qualitative inspection of structural alterations of DMD muscle using a diversity of grading scales, with increasing use of T2map, 44 , 111 , 113 Dixon, 113 and MRS. 44 , 111 These quantitative MRI techniques have allowed a more precise estimation of local or generalized disease severity. Longitudinal studies assessing the effect of an intervention have also become more prominent, in both clinical 44 , 111 and animal model subjects. 88 , 127 , 147 Further studies that quantitatively document the validity of MRI as a longitudinal biomarker to track DMD disease progression in clinical trials, so as to complement functional testing, are critically needed. The publications included are too heterogeneous in their methodology and reporting to perform either meta‐analysis or even assess the risk of bias because quantitative inputs needed to assess the risk of bias are not available.

To better promote the wider application of MRI in assessing DMD in clinical trials across centers and among radiologists, agreement studies are needed to establish the reliability of imaging results. Our review indicated that only 16% of studies assessed agreement. Even though this is slightly higher than the average numbers reported in radiology research, 154 there was little consistency, with most employing different semi‐qualitative gradings or the quality of an ROI. The optimal method to assess the quality of a new imaging method would be to correlate findings to the most accurate and reliable outcomes. Relatively few studies have correlated MRI findings with a gold standard, such as the severity of histopathological lesions or the level of functional impairment, as with the loss of ambulation. Pointing to its sensitivity as a biomarker, studies using quantitative MRI have tended to track better with functional severity than more subjective motor scores that are prone to high observer dependency. 54 Only four papers (3.7%) correlated histopathological findings with semi‐qualitative 77 or quantitative assessment 8 , 94 , 108 of MRI. The increasing use of animal models in recent years should provide an opportunity to assess the accuracy of imaging biomarkers in DMD by correlating findings with systematic lesion scores. In general, all papers reporting correlation experiments used Spearmanʼs rank or Pearsonʼs correlation coefficient. The Pearson correlation coefficient measures the strength of a linear association between two variables and attempts to draw a line of best fit through the data of two variables. Therefore, calculating a Pearson correlation coefficient has a meaningful result only in the case of a linear relation. On the other hand, Spearmanʼs rank correlation coefficient is a nonparametric measure of rank and assesses how well the relationship between two variables can be described using a monotonic function (no assumption on linearity). With no reasoning behind the use of either of these statistical instruments, the choice appeared rather arbitrary.

The characteristic histopathological lesions of DMD, including myofiber necrosis and regeneration, inflammation, fat deposition, and fibrosis, lend themselves to assessment by texture analysis methods. In this systematic review, a comparison between the performance of different methods for a certain classification task was not possible due to the large variety in the datasets used and the classification tasks posed. Identification of new, optimal heterogeneity features, including combinations, will require validation against large well‐defined datasets from other clinical outcomes. The design of future studies should also take into account requirements from pattern recognition, that is, a balanced number of subjects and features, cross‐validation, independent test datasets, and prospective study design. Satisfying these requirements would allow a more reliable evaluation of the value of heterogeneity features.

We were particularly concerned about the bias in the studies included 36 : selection bias arising from differences in baseline characteristics of patient populations being compared, performance bias arising from unequal care beyond the treatment being compared, and detection bias arising from the variable assessment of outcomes potentially prevalent in MRI studies. To account for potential bias, we scored 23 DMD longitudinal studies using the NOS, with all but one having high or moderate values, consistent with a good quality paper. During the period our study was under review, an additional systematic review was published 155 that assessed papers correlating muscle MRI and function in DMD patients. Ropars et al. 155 assessed the potential for bias and associated quality of these papers using the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist with three of 17 included papers appraised as low quality.

Clearly, in our study and this other recent DMD systematic review, conclusions and associated recommendations should be weighted toward high‐quality papers. However, these studies often suffered from other design problems, including small sample sizes that could result in chance findings. There was also the potential for prevalence‐incidence (Neyman) bias that arises due to patients with either mild or severe disease being excluded. 156 For instance, individuals with severe DMD are often not studied, causing a potential error in the estimated association between treatment and an outcome. Similarly, the impact of corticosteroids was not always considered, introducing possible performance bias. Furthermore, the choice of functional ability as the main outcome in many studies introduced the potential for apprehension bias. 157 Finally, with regard to bias, given the natural tendency to not publish negative findings, the results of this systematic review are probably skewed towards positive results. Studies in which MRI did not track with disease severity likely were underreported.

Despite the limitations of this study, we established that the broader use of qMRI in DMD has led to a desirable increase in quantitative versus semi‐qualitative biomarkers, and a tendency to validate findings against objective histopathological and functional outcome parameters. However, without the incorporation of MRI into larger clinical trials, this effort will have minimal impact.

4.1. Recommendations for the clinician

Since the available data are insufficient to propose a specific acquisition protocol or method of image analysis, we recommend that future work emphasize MRI techniques aimed at measuring fat deposition, edema, myofiber necrosis and regeneration, inflammation, and fibrosis. This necessitates a multiparametric and quantitative approach. This will likely include T1‐mapping, T2‐mapping, Dixon methods (for fat and water quantification), DTI, and/or MRS. Specifically, the clinician should aim to quantify fat deposition and edema using sequences with and without chemical fat saturation or short tau inversion recovery. Clinicians are encouraged to include functional MRI in order to better understand the features of the disease and detect the therapeutic effect. For example, information obtained from DTI and MRS provides exciting insights into skeletal muscle substructure and metabolism. Emerging MRI methods should also be considered. The development and refinement of semi‐automated image analysis techniques are expected to further improve precision. Importantly, efforts should be made to assess and improve the repeatability of measurements and to correlate MRI findings with histology at the local level.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

JNK is a paid consultant for Solid Biosciences.

ETHICAL PUBLICATION STATEMENT

We confirm that we have read the Journalʼs position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supporting Information.

Alic L, Griffin JF IV, Eresen A, Kornegay JN, Ji JX. Using MRI to quantify skeletal muscle pathology in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: A systematic mapping review. Muscle & Nerve. 2021;64:8–22. 10.1002/mus.27133

REFERENCES

- 1. Datta N, Ghosh PS. Update on muscular dystrophies with focus on novel treatments and biomarkers. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020;20(6):14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chrzanowski SM, Darras BT, Rutkove SB. The value of imaging and composition‐based biomarkers in Duchenne muscular dystrophy clinical trials. Neurotherapeutics. 2020;17(1):142‐152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gutpell K, Hoffman L. Non‐invasive assessment of skeletal muscle pathology and treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. OA Musculoskelet Med. 2013;1(4):1‐5. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ten Dam L, van der Kooi AJ, Verhamme C, Wattjes MP, de Visser M. Muscle imaging in inherited and acquired muscle diseases. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23(4):688‐703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jiddane M, Gastaut JL, Pellissier JF, Pouget J, Serratrice G, Salamon G. CT of primary muscle diseases. Am J Neuroradiol. 1983;4(3):773‐776. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim HK, Laor T, Horn PS, Racadio JM, Wong B, Dardzinski BJ. T2 mapping in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: distribution of disease activity and correlation with clinical assessments. Radiology. 2010;255(3):899‐908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vill K, Sehri M, Müller C, et al. Qualitative and quantitative muscle ultrasound in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: where do sonographic changes begin? Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2020;28:142‐150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fan Z, Wang J, Ahn M, et al. Characteristics of magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers in a natural history study of golden retriever muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2014;24(2):178‐191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chrzanowski SM, Baligand C, Willcocks RJ, et al. Multi‐slice MRI reveals heterogeneity in disease distribution along the length of muscle in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Acta Myol. 2017;36(3):151‐162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Polavarapu K, Manjunath M, Preethish‐Kumar V, et al. Muscle MRI in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: evidence of a distinctive pattern. Neuromuscul Disord. 2016;26(11):768‐774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bonati U, Hafner P, Schadelin S, et al. Quantitative muscle MRI: a powerful surrogate outcome measure in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2015;25(9):679‐685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eresen A, Alic L, Birch SM, et al. Texture as an imaging biomarker for disease severity in golden retriever muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2019;59(3):380‐386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eresen A, Alic L, Kornegay J, Ji JX. Assessment of disease severity in a canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: classification of quantitative MRI. In: 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), IEEE; 2018:648‐651. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14. Eresen A, Hafsa NE, Alic L, et al. Muscle percentage index as a marker of disease severity in golden retriever muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2019;60(5):621‐628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li GD, Liang YY, Xu P, Ling J, Chen YM. Diffusion‐tensor imaging of thigh muscles in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: correlation of apparent diffusion coefficient and fractional anisotropy values with fatty infiltration. Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206(4):867‐870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nitz WR, Reimer P. Contrast mechanisms in MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 1999;9(6):1032‐1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taylor AJ, Salerno M, Dharmakumar R, Jerosch‐Herold M. T1 mapping: basic techniques and clinical applications. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(1):67‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim PK, Hong YJ, Im DJ, et al. Myocardial T1 and T2 mapping: techniques and clinical applications. Korean J Radiol. 2017;18(1):113‐131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Manenti G, Carlani M, Mancino S, et al. Diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging of prostate cancer. Invest Radiol. 2007;42(6):412‐419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dixon WT. Simple proton spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 1984;153(1):189‐194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Glover GH, Schneider E. Three‐point Dixon technique for true water/fat decomposition with B0 inhomogeneity correction. Magn Reson Med. 1991;18(2):371‐383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu GC, Jong YJ, Chiang CH, Jaw TS. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: MR grading system with functional correlation. Radiology. 1993;186(2):475‐480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Olsen DB, Gideon P, Jeppesen TD, Vissing J. Leg muscle involvement in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy assessed by MRI. J Neurol. 2006;253(11):1437‐1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mercuri E, Talim B, Moghadaszadeh B, et al. Clinical and imaging findings in six cases of congenital muscular dystrophy with rigid spine syndrome linked to chromosome 1p (RSMD1). Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12(7):631‐638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carlo B, Roberta P, Stramare R, Fanin M, Angelini C. Limb‐girdle muscular dystrophies type 2A and 2B: clinical and radiological aspects. Basic Appl Myol. 2006;16:17‐25. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marden FA, Connolly AM, Siegel MJ, Rubin DA. Compositional analysis of muscle in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy using MR imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34(3):140‐148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Forbes SC, Willcocks RJ, Triplett WT, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy assessment of lower extremity skeletal muscles in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a multicenter cross sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Triplett WT, Baligand C, Forbes SC, et al. Chemical shift‐based MRI to measure fat fractions in dystrophic skeletal muscle. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72(1):8‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Haralick RM, Shanmugam K, Dinstein IH. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1973;SMC‐3(6):610‐621. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Amadasun M, King R. Textural features corresponding to textural properties. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybernet. 1989;19(5):1264‐1274. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Galloway MM. Texture analysis using gray level run lengths. Comput Graph Image Process. 1975;4(2):172‐180. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ojala T, Pietikainen M, Maenpaa T. Texture analysis using gray level run lengths. Comput Graph Image Process. 2002;24(7):971‐978. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2001;323(7304):101‐105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wells G, Shea B, Oʼconnell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P, Ga SW, Zello GA, Petersen J. The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta‐Analyses. 2014.

- 36. Egger M, Smith GD, Sterne JA. Uses and abuses of meta‐analysis. Clin Med (Lond). 2001;1(6):478‐484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim HK, Merrow AC, Shiraj S, Wong BL, Horn PS, Laor T. Analysis of fatty infiltration and inflammation of the pelvic and thigh muscles in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD): grading of disease involvement on MR imaging and correlation with clinical assessments. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43(10):1327‐1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Akima H, Lott D, Senesac C, et al. Relationships of thigh muscle contractile and non‐contractile tissue with function, strength, and age in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012;22(1):16‐25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Arpan I, Forbes SC, Lott DJ, et al. T(2) mapping provides multiple approaches for the characterization of muscle involvement in neuromuscular diseases: a cross‐sectional study of lower leg muscles in 5‐15‐year‐old boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. NMR Biomed. 2013;26(3):320‐328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Arpan I, Willcocks RJ, Forbes SC, et al. Examination of effects of corticosteroids on skeletal muscles of boys with DMD using MRI and MRS. Neurology. 2014;83(11):974‐980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Banerjee B, Sharma U, Balasubramanian K, Kalaivani M, Kalra V, Jagannathan NR. Effect of creatine monohydrate in improving cellular energetics and muscle strength in ambulatory Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients: a randomized, placebo‐controlled 31P MRS study. Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;28(5):698‐707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Barany M, Venkatasubramanian PN, Mok E, et al. Quantitative and qualitative fat analysis in human leg muscle of neuromuscular diseases by 1H MR spectroscopy in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 1989;10(2):210‐226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Barnard AM, Lott DJ, Batra A, et al. Imaging respiratory muscle quality and function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol. 2019;266(11):2752‐2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Barnard AM, Willcocks RJ, Finanger EL, et al. Skeletal muscle magnetic resonance biomarkers correlate with function and sentinel events in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Batra A, Vohra RS, Chrzanowski SM, et al. Effects of PDE5 inhibition on dystrophic muscle following an acute bout of downhill running and endurance training. J Appl Physiol. 2019;126(6):1737‐1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bensamoun SF, Charleux F, Debernard L, Themar‐Noel C, Voit T. Elastic properties of skeletal muscle and subcutaneous tissues in Duchenne muscular dystrophy by magnetic resonance elastography (MRE): a feasibility study. IRBM. 2015;36(1):4‐9. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bing Q, Hu K, Tian Q, et al. Semi‐quantitative assessment of lower limb MRI in dystrophinopathy. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9(7):13723‐13732. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bish LT, Sleeper MM, Forbes SC, et al. Long‐term systemic myostatin inhibition via liver‐targeted gene transfer in golden retriever muscular dystrophy. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22(12):1499‐1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brogna C, Cristiano L, Tartaglione T, et al. Functional levels and MRI patterns of muscle involvement in upper limbs in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0199222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cole MA, Rafael JA, Taylor DJ, Lodi R, Davies KE, Styles P. A quantitative study of bioenergetics in skeletal muscle lacking utrophin and dystrophin. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12(3):247‐257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Duda D. Multi‐muscle MRI texture analysis for therapy evaluation in duchenne muscular dystrophy. computer information systems and industrial management. In: IFIP International Conference on Computer Information Systems and Industrial Management. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019:12‐24.

- 52. Dunn JF, Tracey I, Radda GK. Exercise metabolism in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a biochemical and [31P]‐nuclear magnetic resonance study of mdx mice. Proc Biol Sci. 1993;251(1332):201‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dunn JF, Zaim‐Wadghiri Y. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22(10):1367‐1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fischmann A, Hafner P, Gloor M, et al. Quantitative MRI and loss of free ambulation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol. 2013;260(4):969‐974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Forbes SC, Walter GA, Rooney WD, et al. Skeletal muscles of ambulant children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: validation of multicenter study of evaluation with MR imaging and MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 2013;269(1):198‐207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gaeta M, Messina S, Mileto A, et al. Muscle fat‐fraction and mapping in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: evaluation of disease distribution and correlation with clinical assessments. Preliminary experience. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(8):955‐961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Garrood P, Hollingsworth KG, Eagle M, et al. MR imaging in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: quantification of T1‐weighted signal, contrast uptake, and the effects of exercise. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30(5):1130‐1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gerhalter T, Gast LV, Marty B, et al. 23Na MRI depicts early changes in ion homeostasis in skeletal muscle tissue of patients with duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;50(4):1103‐1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Godi C, Ambrosi A, Nicastro F, et al. Longitudinal MRI quantification of muscle degeneration in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3(8):607‐622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Goudemant JF, Deconinck N, Tinsley JM, et al. Expression of truncated utrophin improves pH recovery in exercising muscles of dystrophic mdx mice: a 31P NMR study. Neuromuscul Disord. 1998;8(6):371‐379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Griffiths RD, Cady EB, Edwards RH, Wilkie DR. Muscle energy metabolism in Duchenne dystrophy studied by 31P‐NMR: controlled trials show no effect of allopurinol or ribose. Muscle Nerve. 1985;8(9):760‐767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Heier CR, Guerron AD, Korotcov A, et al. Non‐invasive MRI and spectroscopy of mdx mice reveal temporal changes in dystrophic muscle imaging and in energy deficits. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hogrel JY, Wary C, Moraux A, et al. Longitudinal functional and NMR assessment of upper limbs in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2016;86(11):1022‐1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hollingsworth KG, Garrood P, Eagle M, Bushby K, Straub V. Magnetic resonance imaging in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: longitudinal assessment of natural history over 18 months. Muscle Nerve. 2013;48(4):586‐588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hooijmans MT, Damon BM, Froeling M, et al. Evaluation of skeletal muscle DTI in patients with duchenne muscular dystrophy. NMR Biomed. 2015;28(11):1589‐1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hooijmans MT, Doorenweerd N, Baligand C, et al. Spatially localized phosphorous metabolism of skeletal muscle in Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients: 24‐month follow‐up. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hooijmans MT, Niks EH, Burakiewicz J, et al. Non‐uniform muscle fat replacement along the proximodistal axis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27(5):458‐464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hooijmans MT, Niks EH, Burakiewicz J, Verschuuren JJ, Webb AG, Kan HE. Elevated phosphodiester and T2 levels can be measured in the absence of fat infiltration in Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. NMR Biomed. 2017;30(1):e3667. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/nbm.3667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hsieh TJ, Jaw TS, Chuang HY, Jong YJ, Liu GC, Li CW. Muscle metabolism in Duchenne muscular dystrophy assessed by in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33(1):150‐154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hsieh TJ, Wang CK, Chuang HY, Jong YJ, Li CW, Liu GC. In vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy assessment for muscle metabolism in neuromuscular diseases. J Pediatr. 2007;151(3):319‐321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Huang Y, Majumdar S, Genant HK, et al. Quantitative MR relaxometry study of muscle composition and function in duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1994;4(1):59‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ikehira H, Nishikawa S, Matsumura K, Hasegawa T, Arimizu N, Tateno Y. The functional staging of Duchenne muscular dystrophy using in vivo 31P MR spectroscopy. Radiat Med. 1995;13(2):63‐65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Johnston JH, Kim HK, Merrow AC, et al. Quantitative skeletal muscle MRI: part 1, derived T2 fat map in differentiation between boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and healthy boys. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(2):W207‐W215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kemp GJ, Taylor DJ, Dunn JF, Frostick SP, Radda GK. Cellular energetics of dystrophic muscle. J Neurol Sci. 1993;116(2):201‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kim HK, Laor T, Horn PS, Wong B. Quantitative assessment of the T2 relaxation time of the gluteus muscles in children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a comparative study before and after steroid treatment. Korean J Radiol. 2010;11(3):304‐311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kim HK, Serai S, Lindquist D, et al. Quantitative skeletal muscle MRI: part 2, MR spectroscopy and T2 relaxation time mapping‐comparison between boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and healthy boys. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(2):W216‐W223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kinali M, Arechavala‐Gomeza V, Cirak S, et al. Muscle histology vs MRI in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2011;76(4):346‐353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kobayashi M, Nakamura A, Hasegawa D, Fujita M, Orima H, Takeda S. Evaluation of dystrophic dog pathology by fat‐suppressed T2‐weighted imaging. Muscle Nerve. 2009;40(5):815‐826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kornegay JN, Bogan DJ, Bogan JR, et al. Dystrophin‐deficient dogs with reduced myostatin have unequal muscle growth and greater joint contractures. Skelet Muscle. 2016;6:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kornegay JN, Li J, Bogan JR, et al. Widespread muscle expression of an AAV9 human mini‐dystrophin vector after intravenous injection in neonatal Dystrophin‐deficient dogs. Mol Ther. 2010;18(8):1501‐1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kornegay JN, Peterson JM, Bogan DJ, et al. NBD delivery improves the disease phenotype of the golden retriever model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Skelet Muscle. 2014;4:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Latroche C, Matot B, Martins‐Bach A, et al. Structural and functional alterations of skeletal muscle microvasculature in dystrophin‐deficient mdx mice. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(9):2482‐2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Le Guiner C, Montus M, Servais L, et al. Forelimb treatment in a large cohort of dystrophic dogs supports delivery of a recombinant AAV for exon skipping in Duchenne patients. Mol Ther. 2014;22(11):1923‐1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lee‐McMullen B, Chrzanowski SM, Vohra R, et al. Age‐dependent changes in metabolite profile and lipid saturation in dystrophic mice. NMR Biomed. 2019;32(5):e4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Leroy‐Willig A, Willig TN, Henry‐Feugeas MC, et al. Body composition determined with MR in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, and normal subjects. Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;15(7):737‐744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Li W, Zheng Y, Zhang W, Wang Z, Xiao J, Yuan Y. Progression and variation of fatty infiltration of the thigh muscles in Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a muscle magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuromuscul Disord. 2015;25(5):375‐380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Li Z, Zeng H, Han C, et al. Effectiveness of high‐speed T2‐corrected multiecho MR spectroscopic method for quantifying thigh muscle fat content in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am J Roentgenol. 2019;212(6):1354‐1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Loehr JA, Stinnett GR, Hernandez‐Rivera M, et al. Eliminating Nox2 reactive oxygen species production protects dystrophic skeletal muscle from pathological calcium influx assessed in vivo by manganese‐enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Physiol. 2016;594(21):6395‐6405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lott DJ, Forbes SC, Mathur S, et al. Assessment of intramuscular lipid and metabolites of the lower leg using magnetic resonance spectroscopy in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2014;24(7):574‐582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Mankodi A, Azzabou N, Bulea T, et al. Skeletal muscle water T2 as a biomarker of disease status and exercise effects in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27(8):705‐714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Mankodi A, Bishop CA, Auh S, Newbould RD, Fischbeck KH, Janiczek RL. Quantifying disease activity in fatty‐infiltrated skeletal muscle by IDEAL‐CPMG in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2016;26(10):650‐658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Martins‐Bach AB, Malheiros J, Matot B, et al. Quantitative T2 combined with texture analysis of nuclear magnetic resonance images identify different degrees of muscle involvement in three mouse models of muscle dystrophy: mdx, Large myd and mdx/Large myd . PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Mathur S, Lott DJ, Senesac C, et al. Age‐related differences in lower‐limb muscle cross‐sectional area and torque production in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(7):1051‐1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Mathur S, Vohra RS, Germain SA, et al. Changes in muscle T2 and tissue damage after downhill running in mdx mice. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43(6):878‐886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Matsumura K, Nakano I, Fukuda N, Ikehira H, Tateno Y, Aoki Y. Proton spin‐lattice relaxation time of Duchenne dystrophy skeletal muscle by magnetic resonance imaging. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11(2):97‐102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Matsumura K, Nakano I, Fukuda N, Ikehira H, Tateno Y, Aoki Y. Duchenne muscular dystrophy carriers. Proton spin‐lattice relaxation times of skeletal muscles on magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroradiology. 1989;31(5):373‐376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Mavrogeni S, Papavasiliou A, Douskou M, Kolovou G, Papadopoulou E, Cokkinos DV. Effect of deflazacort on cardiac and sternocleidomastoid muscles in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2009;13(1):34‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Mavrogeni S, Tzelepis GE, Athanasopoulos G, et al. Cardiac and sternocleidomastoid muscle involvement in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an MRI study. Chest. 2005;127(1):143‐148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. McCully K, Giger U, Argov Z, et al. Canine X‐linked muscular dystrophy studied with in vivo phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Muscle Nerve. 1991;14(11):1091‐1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. McMillan AB, Shi D, Pratt SJP, Lovering RM. Diffusion tensor MRI to assess damage in healthy and dystrophic skeletal muscle after lengthening contractions. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:970726‐970726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Nagy S, Schädelin S, Hafner P, et al. Longitudinal reliability of outcome measures in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2020;61(1):63‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Nagy S, Schmidt S, Hafner P, et al. Measurements of motor function and other clinical outcome parameters in ambulant children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Vis Exp. 2019;143:e58784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Newman RJ, Bore PJ, Chan L, et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of forearm muscle in Duchenne dystrophy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;284(6322):1072‐1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Park J, Wicki J, Knoblaugh SE, Chamberlain JS, Lee D. Multi‐parametric MRI at 14T for muscular dystrophy mice treated with AAV vector‐mediated gene therapy. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Park JS, Vohra R, Klussmann T, Bengtsson NE, Chamberlain JS, Lee D. Non‐invasive tracking of disease progression in young dystrophic muscles using multi‐parametric MRI at 14T. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0206323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Pichiecchio A, Uggetti C, Egitto MG, et al. Quantitative MR evaluation of body composition in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Eur Radiol. 2002;12(11):2704‐2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ponrartana S, Ramos‐Platt L, Wren TA, et al. Effectiveness of diffusion tensor imaging in assessing disease severity in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: preliminary study. Pediatr Radiol. 2015;45(4):582‐589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Qin EC, Juge L, Lambert SA, Paradis V, Sinkus R, Bilston LE. In vivo anisotropic mechanical properties of dystrophic skeletal muscles measured by anisotropic MR elastographic imaging: the mdx mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Radiology. 2014;273(3):726‐735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Qureshi MM, McClure WC, Arevalo NL, et al. The dietary supplement protandim decreases plasma osteopontin and improves markers of oxidative stress in muscular dystrophy mdx mice. J Diet Suppl. 2010;7(2):159‐178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Reyngoudt H, Lopez Kolkovsky AL, Carlier PG. Free intramuscular Mg2+ concentration calculated using both 31P and 1H NMRS‐based pH in the skeletal muscle of Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. NMR Biomed. 2019;32(9):e4115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Reyngoudt H, Turk S, Carlier PG. (1) H NMRS of carnosine combined with (31) P NMRS to better characterize skeletal muscle pH dysregulation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. NMR Biomed. 2018;31(1):e3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Ricotti V, Evans MR, Sinclair CD, et al. Upper limb evaluation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: fat‐water quantification by MRI, muscle force and function define endpoints for clinical trials. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0162542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Schmidt S, Hafner P, Klein A, et al. Timed function tests, motor function measure, and quantitative thigh muscle MRI in ambulant children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a cross‐sectional analysis. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28(1):16‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Schreiber A, Smith WL, Ionasescu V, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Radiol. 1987;17(6):495‐497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Selzo MR, Kornegay JN, Spaulding KA, Bettis A, Snook E, Styner M, Wang J, Gallippi CM. VisR ultrasound evaluation of dystrophic muscle degeneration in a dog cross‐section and comparison to histology and MRI. In: 2015 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Taipei, Taiwan. IEEE; 2015: 1‐4.

- 116. Sharma R, Agarwala AK. Metabolomics by imaging; biochemical‐magnetic resonance correlation: what we learn from combined data of magnetic resonance spectroscopy, NMR spectroscopy, clinical chemistry and tissue content analysis? Major bottlenecks in diagnosis. Recent Pat Med Imaging. 2012;2:130‐149. [Google Scholar]

- 117. Straub V, Donahue KM, Allamand V, Davisson RL, Kim YR, Campbell KP. Contrast agent‐enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of skeletal muscle damage in animal models of muscular dystrophy. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(4):655‐659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Suput D, Zupan A, Sepe A, Demsar F. Discrimination between neuropathy and myopathy by use of magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Neurol Scand. 1993;87(2):118‐123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Tardif‐de Gery S, Vilquin J, Carlier P, et al. Muscular transverse relaxation time measurement by magnetic resonance imaging at 4 Tesla in normal and dystrophic dy/dy and dy(2j)/dy(2j) mice. Neuromuscul Disord. 2000;10(7):507‐513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Thibaud JL, Azzabou N, Barthelemy I, et al. Comprehensive longitudinal characterization of canine muscular dystrophy by serial NMR imaging of GRMD dogs. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012;22(suppl 2):S85‐S99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Thibaud JL, Matot B, Barthelemy I, Fromes Y, Blot S, Carlier PG. Anatomical and mesoscopic characterization of the dystrophic diaphragm: An in vivo nuclear magnetic resonance imaging study in the Golden retriever muscular dystrophy dog. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27(4):315‐325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Thibaud JL, Monnet A, Bertoldi D, Barthelemy I, Blot S, Carlier PG. Characterization of dystrophic muscle in golden retriever muscular dystrophy dogs by nuclear magnetic resonance imaging. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007;17(7):575‐584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Torriani M, Townsend E, Thomas BJ, Bredella MA, Ghomi RH, Tseng BS. Lower leg muscle involvement in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an MR imaging and spectroscopy study. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(4):437‐445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Vohra R, Accorsi A, Kumar A, Walter G, Girgenrath M. Magnetic resonance imaging is sensitive to pathological amelioration in a model for laminin‐deficient congenital muscular dystrophy (MDC1A). PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Vohra R, Batra A, Forbes SC, Vandenborne K, Walter GA. Magnetic resonance monitoring of disease progression in mdx mice on different genetic backgrounds. Am J Pathol. 2017;187(9):2060‐2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Vohra RS, Lott D, Mathur S, et al. Magnetic resonance assessment of hypertrophic and pseudo‐hypertrophic changes in lower leg muscles of boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and their relationship to functional measurements. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Vohra RS, Mathur S, Bryant ND, Forbes SC, Vandenborne K, Walter GA. Age‐related T2 changes in hindlimb muscles of mdx mice. Muscle Nerve. 2016;53(1):84‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Voisin V, Sebrie C, Matecki S, et al. L‐arginine improves dystrophic phenotype in mdx mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20(1):123‐130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Walter G, Cordier L, Bloy D, Sweeney HL. Noninvasive monitoring of gene correction in dystrophic muscle. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54(6):1369‐1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Walter GA, Cahill KS, Huard J, et al. Noninvasive monitoring of stem cell transfer for muscle disorders. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51(2):273‐277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Wang J, Fan Z, Vandenborne K, et al. Statistical texture analysis based MRI quantification of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in a canine model. Proc. SPIE 8672, Medical Imaging 2013: Biomedical Applications in Molecular, Structural, and Functional Imaging, 86720F (29 March 2013); 10.1117/12.2006892. [DOI]

- 132. Wang J, Fan Z, Vandenborne K, et al. A computerized MRI biomarker quantification scheme for a canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2013;8(5):763‐774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Wary C, Azzabou N, Giraudeau C, et al. Quantitative NMRI and NMRS identify augmented disease progression after loss of ambulation in forearms of boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. NMR Biomed. 2015;28(9):1150‐1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Wary C, Naulet T, Thibaud JL, Monnet A, Blot S, Carlier PG. Splitting of Pi and other (3)(1)P NMR anomalies of skeletal muscle metabolites in canine muscular dystrophy. NMR Biomed. 2012;25(10):1160‐1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Weber MA, Nagel AM, Jurkat‐Rott K, Lehmann‐Horn F. Sodium (23Na) MRI detects elevated muscular sodium concentration in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2011;77(23):2017‐2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]