dear editor, Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a painful chronic inflammatory skin disease that impacts quality of life substantially. Its prevalence is estimated to be 0·7%. 1 Various pathophysiological hypotheses exist, but there is no therapeutic consensus, which complicates the management of patients with HS.

Therefore, the Centre of Evidence of the French Society of Dermatology initiated a standardized recommendation process for HS. A 13‐member working group (WG) was formed, comprising dermatologists (A.B., E.S., M.M.‐B., I.B.‐V., N.J., J.‐F.S.), a plastic surgeon (P.P.), an emergency physician (Y.Y.), an infectious diseases specialist (E.C.), a microbiologist (O.J.‐L.), a psychologist (K.C.), a general practitioner (S.S.) and a patient representative from an HS patient association. Members had no conflicts of interest and a strict methodology was followed. 2 Firstly, a systematic review of the literature was performed to compile references from study inception to September 2018. Assistance was provided by the French National Health Authority medical health librarian (supporting information available on request from the author). Eight physicians specializing in methodology then extracted data from each report (supporting information available on request from the author) and analysed the methodology and risk of bias using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation instrument for guidelines, the Assessing Methodological quality for Systematic Reviews tool for systematic reviews and the risk‐of‐bias tool for randomized controlled trials (Cochrane Collaboration). 3 Observational studies were retained if they included more than 20 patients. Senior experts were interviewed and their comments were incorporated into the manuscript. Finally, the draft recommendations were submitted to a multidisciplinary panel of 36 reviewers.

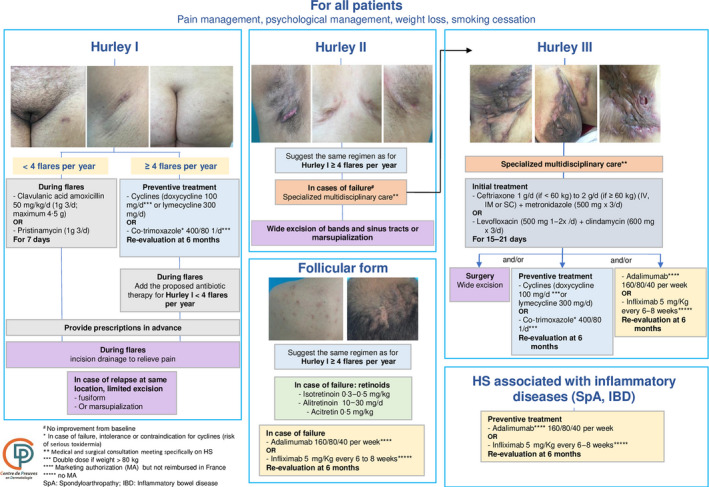

The most important recommendations, supported by both evidence‐ and expertise‐based data, were used to design a decision‐making algorithm (Figure 1).

-

(i)

Hurley stage I or II – use of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid or pristinamycin for 7 days; for preventive treatment or postacute care, co‐trimoxazole or cyclines; for follicular HS (‘punched‐out’ scars, ice‐pick scars, follicular epidermal cysts, comedones and pilonidal sinus), oral retinoid.

-

(ii)

Hurley stage II or III – ceftriaxone/metronidazole or levofloxacin/clindamycin for 15–21 days. Anti‐tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α can be proposed, but should be re‐evaluated within 3–6 months. Specialized, multidisciplinary care (involving a dermatologist and a surgeon, at least) is recommended for severe cases.

Figure 1.

French guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) management: treatment algorithm for HS in adults. d, day; IV, intravenous; IM, intramuscular; SC, subcutaneous; PO, per os.

A medicosurgical approach is strongly recommended for all patients, either after or in combination with medical steps. Surgery (assisted by ultrasounds, probes, etc.) is considered a curative treatment for specific lesions, but surgeons must fully understand the need to maintain adequate margins, as in skin carcinoma surgery, to achieve remission.

After final proofreading by the Centre of Evidence (O.C., M.B.‐B)., the algorithm was published on a dedicated open‐access website to provide a user‐friendly and practical tool featuring fast, step‐by‐step navigation according to clinical situations (https://reco.sfdermato.org/en/).

It should be noted that several of our recommendations differ from other guidelines (supporting information available on request from the author).

-

(i)

As topical antibiotics and antiseptics have a low level of evidence and present a high risk of bacterial resistance, the WG recommends the use of soap and water as an alternative. 4

-

(ii)

For Hurley stage I or II, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid or pristinamycin (which act synergistically against Gram‐positive and anaerobic bacteria) for 7 days is recommended because of their antimicrobial spectrum covering bacteria associated with HS lesions, including anaerobes.

-

(iii)

Cyclines can be prescribed for preventive treatment or postacute disease, as proposed in other guidelines, but co‐trimoxazole (at low doses) was suggested by the WG owing to its susceptibility rate, in addition to its immunomodulatory and anti‐inflammatory properties. 5

-

(iv)

The combination of oral clindamycin and rifampicin was not recommended for the following reasons: there is insufficient follow‐up data in observational studies; enzyme induction reduces the level of clindamycin by 82%; 6 clinicians have insufficient knowledge regarding the modalities of rifampicin absorption; and especially because of the risk of developing antibiotic resistance to this treatment. 7

-

(v)

For Hurley stage II or III, an optimized combination of antibiotics with large spectral action on bacteria (ceftriaxone/metronidazole or levofloxacin/clindamycin) 8 is recommended, as long as they are used at an antibiotic dose, for a maximum of 21 days and without any contraindication to the use of fluoroquinolone. 5

-

(vi)

The WG considered the level of evidence insufficient to recommend a list of miscellaneous drugs, including intralesional corticosteroids, dapsone and ciclosporin.

-

(vii)

For HS associated with inflammatory diseases, such as Crohn disease or spondyloarthropathy, preventive treatment with anti‐TNF‐α is recommended, in agreement with gastroenterologists or rheumatologists.

-

(viii)

The WG highlighted the importance of following recommendations for complete wide margins during surgical management to achieve resection, taking the subclinical peripheral extension of HS lesions into account, in accordance with the model for oncological skin surgery.

HS is a chronic disease requiring long‐term and multidisciplinary management that takes into consideration the pain and psychological impact, the different medical and surgical treatments available and the preservation of the microbial ecology.

Author Contribution

Antoine Bertolotti: Data curation (lead); Formal analysis (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Resources (equal); Writing‐original draft (lead). Emilie Sbidian: Conceptualization (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Methodology (lead); Project administration (equal); Resources (equal); Supervision (equal); Validation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Olivier Join‐Lambert: Formal analysis (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Resources (equal); Validation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Isabelle Bourgault: Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Micheline Moyal‐Barracco: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Resources (equal); Validation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Pierre Perrot: Investigation (equal); Validation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Nicole Jouan: Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Youri Yordanov: Investigation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Stéphanie Sidorkiewicz: Investigation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Karine Chazelas: Investigation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Marie‐France Bru‐Daprés: Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Eric Caumes: Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Validation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Jean‐François Sei: Conceptualization (lead); Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Project administration (lead); Supervision (lead); Validation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Olivier Chosidow: Project administration (supporting); Software (supporting); Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Marie Beylot‐Barry: Software (lead); Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal).

Supporting information

File S1 Full list of affiliations and acknowledgments.

Acknowledgments

a full list of acknowledgments is available in File S1 (see Supporting Information).

The complete list of author affiliations is available in File S1 (see Supporting Information).

Funding sources: this work was supported by the French Society of Dermatology.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Ingram JR, Jenkins‐Jones S, Knipe DW et al. Population‐based Clinical Practice Research Datalink study using algorithm modelling to identify the true burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol 2018; 178:917–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haute Autorité de Santé . Practice Guidelines ‘Clinical practice guidelines’ method. Available at: http://www.has‐sante.fr/portail/jcms/c_2040454/en/methodology‐for‐guideline‐development (last accessed 6 December 2019).

- 3. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, (Higgins JPT, Green S, eds), version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). London: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wand ME, Bock LJ, Bonney LC, Sutton JM. Mechanisms of increased resistance to chlorhexidine and cross‐resistance to colistin following exposure of klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates to chlorhexidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 61:e01162–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hessam S, Sand M, Georgas D et al. Microbial profile and antimicrobial susceptibility of bacteria found in inflammatory hidradenitis suppurativa lesions. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2016; 29:161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Join‐Lambert O, Ribadeau‐Dumas F, Jullien V et al. Dramatic reduction of clindamycin plasma concentration in hidradenitis suppurativa patients treated with the rifampin‐clindamycin combination. Eur J Dermatol 2014; 24:94–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Albrecht J, Mehta S, Bigby M. Development of resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis is manageable in hidradenitis suppurativa. Response to ‘Treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with rifampicin: have we forgotten tuberculosis?’. Br J Dermatol 2018; 178:300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Delaunay J, Villani AP, Guillem P et al. Oral ofloxacin and clindamycin as an alternative to the classic rifampicin‐clindamycin in hidradenitis suppurativa: retrospective analysis of 65 patients. Br J Dermatol 2018; 178:e15–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

File S1 Full list of affiliations and acknowledgments.