Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study was to compare childbirth experiences and experience of labor pain in primiparous women who had received high‐ vs low‐dose oxytocin for augmentation of delayed labor.

Material and methods

A multicenter, parallel, double‐blind randomized controlled trial took place in six Swedish labor wards. Inclusion criteria were healthy primiparous women at term with uncomplicated singleton pregnancies, cephalic fetal presentation, spontaneous onset of labor, confirmed delayed labor progress and ruptured membranes. The randomized controlled trial compared high‐ vs low‐dose oxytocin used for augmentation of a delayed labor progress. The Childbirth Experience Questionnaire version 2 (CEQ2) was sent to the women 1 month after birth. The CEQ2 consists of 22 items in four domains: Own capacity, Perceived safety, Professional support and Participation. In addition, labor pain was reported with a visual analog scale (VAS) 2 hours postpartum and 1 month after birth. The main outcome was the childbirth experience measured with the four domains of the CEQ2. The clinical trial number is NCT01587625.

Results

The CEQ2 was sent to 1203 women, and a total of 1008 women (83.8%) answered the questionnaire. The four domains of childbirth experience were scored similarly in the high‐ and low‐dose oxytocin groups of women: Own capacity (P = .36), Perceived safety (P = .44), Professional support (P = .84), Participation (P = .49). VAS scores of labor pain were reported as similar in both oxytocin dosage groups. Labor pain was scored higher 1 month after birth compared with 2 hours postpartum. There was an association between childbirth experiences and mode of birth in both the high‐ and low‐dose oxytocin groups.

Conclusions

Different dosage of oxytocin for augmentation of delayed labor did not affect women’s childbirth experiences assessed through CEQ2 1 month after birth, or pain assessment 2 hours or 1 month after birth.

Keywords: birth, childbirth experience, delayed labor, labor pain, oxytocin augmentation, randomized controlled trial

Abbreviations

- CEQ2

Childbirth Experience Questionnaire version 2

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- VAS

visual analog scale

Key message.

Different dosages of oxytocin to treat delayed labor did not seem to influence women’s childbirth experiences or their pain scores. There was an association between childbirth experiences and mode of birth in both the high‐ and low‐dose oxytocin group.

1. INTRODUCTION

Women’s experiences of childbirth are influenced by various factors and can affect both subsequent labors and life in general, in both a negative and a positive way. 1 , 2 Persistent intensive fear of childbirth, post‐traumatic stress disorder and depression are factors that have been related to a negative childbirth experience. 3 , 4 Two systematic reviews confirmed the impact of a negative childbirth experience on women’s decisions related to childbirth. This comprised the decision to delay a subsequent pregnancy and preference for a cesarean section or a decision to not have another child. 4 , 5

Positive birth experiences have been associated with lower pain scores and an ability to forget labor pain over time, whereas for women with negative birth experiences, the pain scores were high, and the intensity of pain did not change in later years. 2 , 6

Delayed labor progress, a common complication among nulliparous women, 7 has also been associated with a negative birth experience. Augmentation with oxytocin, adverse labor outcome such as emergency cesarean section or instrumental vaginal birth, 7 , 8 and infant transfer to neonatal care are all factors related to a delayed labor progress and have been shown to increase the occurrence of a negative birth experience. 2 , 9 , 10 Women with delayed labor also report feelings of loss of control and a distrust in their own body’s capacity. 11 Primiparous women with delayed labor progress have shown an increased risk of negative and depressive memories of labor 1 month after birth. 12

Use of synthetic oxytocin is the most common treatment for delayed labor progress in current practice. Augmentation with oxytocin is known to shorten labor but its impact on labor outcome is still questioned. 13 Women’s preferences regarding early or expectant augmentation with oxytocin have shown contradictory results. Older studies showed a preference among women for an early treatment with oxytocin. 14 , 15 More recent studies have indicated that women’s childbirth experiences did not differ in relation to early or expectant management of oxytocin use. 12 , 16

There is insufficient knowledge regarding the association between oxytocin dosage and women’s birth experiences. 17 , 18 In a pilot study comparing high‐dose vs low‐dose oxytocin, women’s perception of support and control 2 weeks after birth did not differ between the two groups. 18 However, the response rate was low (63%), and due to unbalanced data and incompleteness in follow‐up, the evidence has been considered weak. 17

We conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in primiparous women and evaluated the effect of a high‐dose or low‐dose oxytocin regimen for augmentation of a delayed labor progress. 19 The primary outcome was the rate of cesarean section and the hypothesis was that a high‐dose oxytocin regimen, compared with a low‐dose, would reduce the number of cesarean sections without a negative effect on maternal and neonatal outcomes. The results of the RCT were published previously. The cesarean section rate did not differ between the high‐dose and the low‐dose oxytocin groups (12.4% vs 12.3%). Women with high‐dose oxytocin had significantly shorter labor duration (mean difference −23.4 minutes), more episodes of uterine tachysystole (43.2% vs 33.5%) and a higher frequency of instrumental vaginal births due to fetal distress (43.8% vs 22.7%). Neonatal outcomes were comparable. 19

The aim of the study reported in this paper was to compare childbirth experiences and experience of labor pain in primiparous women who had received high‐ vs low‐dose oxytocin for augmentation of delayed labor.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

A multicenter, randomized, parallel, double‐blind controlled study was conducted in four maternity units in Sweden including six labor wards: Sahlgrenska University Hospital (SU) in Gothenburg (SU‐East and SU‐Mölndal); Stockholm South General Hospital (SÖS and South BB); NU Hospital Group in Trollhättan and Uppsala University Hospital. 19 Data collection took place between September 2013 and October 2016. The wards entered the study at different time points.

Inclusion criteria were healthy, nulliparous women with uncomplicated singleton pregnancies at term (37+0 to 41+6 gestational weeks), cephalic presentation, spontaneous onset of labor, active phase of labor (regular painful contractions, effaced cervix and dilation ≥3 to 4 cm), confirmed delayed labor progress, and ruptured membranes. 19 Delayed labor was defined using a 3‐hour partogram action line for delay during the first stage of labor or an arrest of the descent of the fetal head for 1‐2 hours during the second stage of labor. 20 Exclusion criteria were as follows: age <18 years, non‐Swedish speaking, previous uterine surgery, clinically significant vaginal bleeding during labor, delayed labor progress with fetal head station below the ischial spines in second stage, suspected disproportion between fetal head and maternal pelvis, abnormal vertex presentation, suspected fetal growth restriction (< −2 standard deviations [SD]), abnormal fetal heart rate (suspicious or pathological cardiotocography), heavy meconium‐stained amniotic fluid, uterine tachysystole (defined as >5 contractions in 10 minutes for >20 minutes), maternal fever and known hypersensitivity to oxytocin therapy.

Eligible women received written and oral information about the study and after consent were randomly allocated to receive a regimen of either a high‐dose or a low‐dose of oxytocin (33.2 µg [20 IU] or 16.6 µg [10] IU oxytocin in 1000 mL isotone saline solution) for augmentation of labor. In the high‐dose group, the infusion started with 6.6 mU/min (20 mL/h) and could be increased to a maximum dose of 59.4 mU/min (180 mL/h). In the low‐dose group the infusion started with 3.3 mU/min (20 mL/h) and could be increased to a maximum dose of 29.7 mU/min (180 mL/h). Randomization was achieved using a computer‐generated randomization sequence. Both randomization and preparation of the oxytocin infusion were conducted blind to the women, the responsible staff and the research team. Primary outcome in the RCT was the rate of emergency cesarean section. The sample size was calculated for the RCT and based on an assumed decrease of the cesarean section rate from 17.5% to 13%, that is, a reduction of 25%. This required a total sample size of 2090 women for 80% power at a significance level of P < .05.

An independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board secured the project management through periodical reviews (six in total) including one interim analysis of study‐specific data.

After the sixth planned safety review, the Data and Safety Monitoring Board recommended termination of the inclusion prior to completion, due to futility. That interim analysis, which included 72 primary endpoint events (including cesarean section) in the high‐dose group and 66 in the low‐dose group (44% of those projected), demonstrated a less than 5% conditional power to demonstrate superiority to a P value <.05 if the trial was carried to completion. Further details on the study design are reported elsewhere. 19

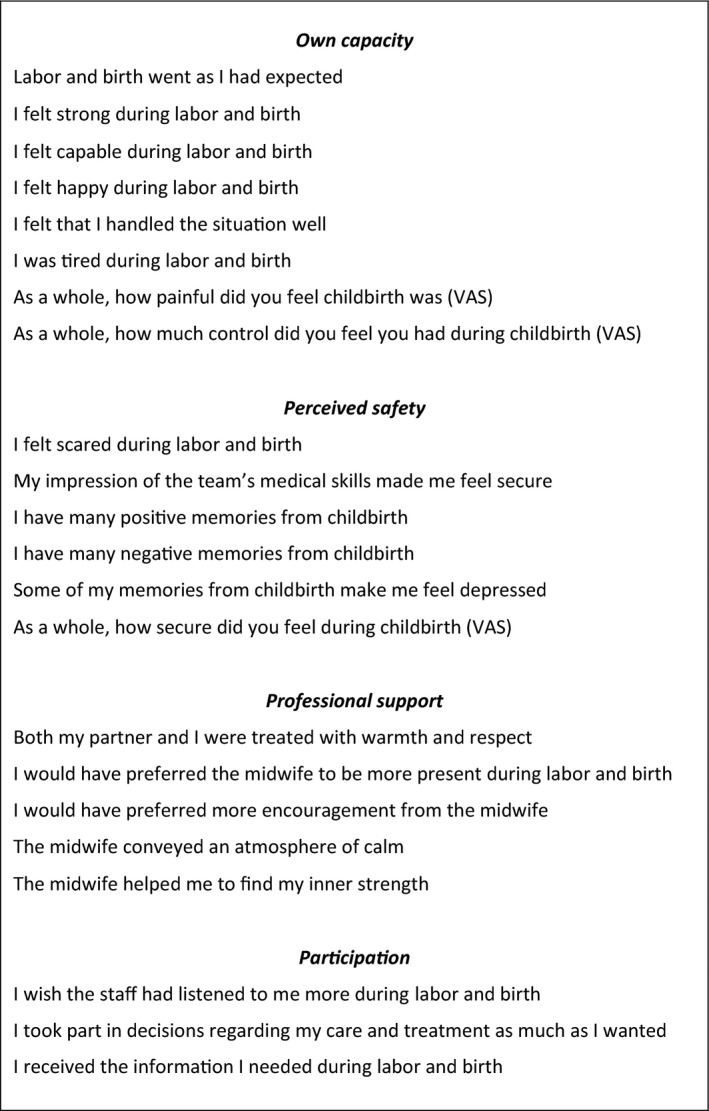

Women’s childbirth experiences related to oxytocin dosage were assessed by the Childbirth Experience Questionnaire version 2 (CEQ2). CEQ2 is validated in Sweden 21 and in the UK 22 and comprises 22 items aggregated into the same four domains as in the first CEQ version: Own capacity (8 items regarding sense of control, personal feelings during childbirth and labor pain), Perceived safety (6 items regarding sense of security and memories of the childbirth) Professional support (5 items about midwifery care) and Participation (3 items regarding possibilities to influence one’s own birthing situation) (Figure 1). The two subscales Perceived safety and Own capacity have remained unchanged from the first CEQ. 23

FIGURE 1.

Domains and items included in the Childbirth Experience Questionnaire 2 (CEQ2)

Most of the items in the four subscales of the CEQ2 were rated on a 4‐point Likert scale as follows: 1 (Totally disagree), 2 (Mostly disagree), 3 (Mostly agree) and 4 (Totally agree). Experience of labor pain, sense of security and control were rated on a 0‐100 visual analog scale (VAS). The VAS scores were classified as 0‐40 = 1, 41‐60 = 2, 61‐80 = 3, and 81‐100 = 4. For the negatively worded items and the pain item, scores were reversed, which gave higher scores for a more positive experience. For each domain a mean score was calculated. The minimum score in each domain was 1 and the maximum score was 4.

Women’s self‐reported experience of labor pain was also assessed 2 hours postpartum at the labor ward with VAS scores 0‐100. This was compared with the self‐reported experience of labor pain 1 month after birth using the VAS scores in the questionnaire. Anchors of both VAS scales were worded as 0 = no pain and 100 = worst possible pain.

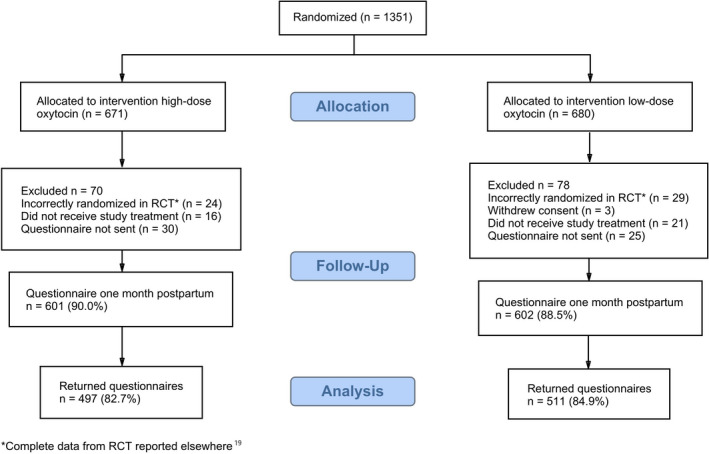

The women received a web‐based form of the CEQ2 by email 1 month after birth. The questionnaire was not sent to women excluded from the RCT or to women who did not receive the oxytocin infusion (Figure 2). To ensure that the questionnaire reached the women, we also sent an SMS text message simultaneously with the email. We tried to reach all women who did not answer, either with a phone call or a text message.

FIGURE 2.

CONSORT flow diagram of participants [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

2.1. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were presented with n (%) and continuous variables with mean and standard deviation (SD). Additionally, for variables presenting characteristics for the study groups, median, first quartile (q1) and third quartile (q3) were reported. For the comparison between groups, the Mann‐Whitney U test was used for continuous variables, Fisher’s Exact test was used for dichotomous variables, and Chi‐square test was used for nonordered categorical variables. Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency reliability of the CEQ2 domains and to compare our results with the recently validated revised instrument CEQ2 questionnaire. 21 Childbirth experiences of women who had spontaneous vaginal births, instrumental vaginal births or cesarean sections in high‐ and low‐dose groups, respectively, were compared with the Kruskal‐Wallis test. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to analyze change in self‐reported experiences of labor pain at the two occasions (2 hours postpartum and 1 month after birth). All significance tests were two‐tailed and a significance level of 0.05 was used.

2.2. Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Board in Gothenburg (Dnr: 090‐12) on 23 March 2012 and by the National Medical Product Agency (Eudra‐CTnr: 2012‐000356‐33). Clinical trial registration number: NCT01587625.

3. RESULTS

Of the 1351 women randomized in the RCT, 671 were allocated to a high‐dose oxytocin regimen and 680 to the low‐dose regimen. Of these, 1203 women (601 in the high‐dose and 602 in the low‐dose group) received the questionnaire 1 month after birth (Table S1). A total of 1008 women answered and returned the questionnaires (83.8% response rate), 497 (82.7%) in the high‐dose group and 511 (84.9%) in the low‐dose group (Figure 2). Nine incorrectly randomized women without a defined delay in labor were included in the analysis.

Maternal characteristics divided into high‐ vs low‐dose groups are shown in Table 1. The total amount of oxytocin given and the maximum dose of oxytocin per minute were higher in the high‐dose group (P = <.001) and labor duration was 29 minutes shorter than in the low‐dose group (P = .018) (Table 1). Mode of delivery, neonatal outcome and other outcomes were similar. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were compatible with those reported in the CEQ2 validation study 21 and were high for the four subscales Own capacity (0.80), Perceived safety (0.84), Professional support (0.81) and Participation (0.77), and for the total scale (0.83).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of study groups

| Variable |

High dose of oxytocin (n = 497) |

Low dose of oxytocin (n = 511) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) |

29.4 (4.7) 29.0 (26; 32) |

29.4 (4.7) 29.0 (26; 32) |

.96 a |

| Gestational age (days) |

282.0 (7.4) 283.0 (277; 287) |

281.6 (6.9) 282.0 (278; 287) |

.24 a |

|

Epidural anesthesia |

432 (86.9) | 438 (85.7) | .58 b |

| Cervical dilation at defined delayed labor (cm) |

6.97 (2.48) 6.00 (5.00; 9.00) n = 478 |

6.92 (2.46) 6.00 (5.00; 9.00) n = 501 |

.75 a |

|

Duration of labor (min) From active phase of labor to birth |

744 (205) 732 (607; 876) n = 495 |

773 (198) 762 (639; 899) n = 511 |

.018 a |

|

Maximum dose of oxytocin (mU/min) (µg/min) |

30.61 (22.89) 26.67 (13.33; 39.83) 0.05(0.04) 0.04 (0.02; 0.07) |

19.50 (11.69) 16.67 (10.00; 26.67) 0.03 (0.02) 0.03 (0.02; 0.04) |

<.001 a |

|

Total oxytocin dose (mU) (µg) |

4816 (5505) 3080 (1620; 5960) 7.92 (8.28) 5.20 (2.70; 10.00) n = 497 |

3613 (3465) 2540 (1300; 4910) 6.01 (5.75) 4.25 (2.20; 8.23) n = 510 |

<.001 a |

| Total duration of oxytocin infusion (hr) |

4.64 (2.98) 3.90 (2.50; 6.30) |

5.29 (3.18) 4.70 (2.90; 7.20) |

<.001 a |

| Mode of delivery | .96 b | ||

| Spontaneous vaginal birth | 364 (73.2%) | 373 (73.0%) | |

| Instrumental vaginal birth | 74 (14.9%) | 79 (15.5%) | |

| Cesarean section | 59 (11.9%) | 59 (11.5%) | |

| Postpartum hemorrhage >1000 mL | 67 (13.5%) | 72 (14.1%) | .79 c |

| Anal sphincter injury (grade 3 or 4) d |

23 (5.3%) n = 438 |

23 (5.1%) n = 452 |

1.00 c |

| Birthweight (g) |

3662 (441) 3650 (3340; 3961) |

3628 (428) 3605 (3330; 3900) |

.24 a |

| Apgar score 5 min < 4 | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1.00 c |

| Apgar score 5 min < 7 | 4 (0.8%) | 9 (1.8%) | .26 c |

| Admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) | 39 (7.8%) | 37 (7.2%) | .72 c |

For categorical variables, n (%) is given.

For continuous variables, mean (SD)/median (Q1; Q3)/ n = is given.

Mann‐Whitney U test.

Chi‐square test.

Fisher’s Exact test.

Percentage of vaginal deliveries.

Childbirth experiences in the four subscales Own capacity, Perceived safety, Professional support and Participation did not differ between the high‐ and low‐dose oxytocin groups (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Comparisons between high‐dose and low‐dose oxytocin and between modes of birth in relation to four domains of Childbirth Experiences Questionnaire 2 (CEQ2)

| Variable |

High dose of oxytocin (n = 497) |

Low dose of oxytocin (n = 511) |

P value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Own capacity | 2.43 (0.55) | 2.46 (0.56) | .36 |

| Spontaneous vaginal birth | 2.49 (0.55) | 2.56 (0.54) | |

| Instrumental vaginal birth | 2.30 (0.54) | 2.16 (0.57) | |

| Cesarean section | 2.19 (0.50) | 2.29 (0.50) | |

| P value b | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Perceived safety | 3.03 (0.72) | 3.06 (0.71) | .44 |

| Spontaneous vaginal birth | 3.15 (0.66) | 3.17 (0.65) | |

| Instrumental vaginal birth | 2.81 (0.74) | 2.81 (0.76) | |

| Cesarean section | 2.54 (0.76) | 2.67 (0.80) | |

| P value b | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Professional support | 3.52 (0.57) | 3.53 (0.52) | .84 |

| Spontaneous vaginal birth | 3.55 (0.55) | 3.58 (0.49) | |

| Instrumental vaginal birth | 3.47 (0.59) | 3.45 (0.58) | |

| Cesarean section | 3.37 (0.62) | 3.29 (0.58) | |

| P value b | .022 | <.001 | |

| Participation | 3.50 (0.65) | 3.53 (0.60) | .49 |

| Spontaneous vaginal birth | 3.56 (0.62) | 3.60 (0.53) | |

| Instrumental vaginal birth | 3.34 (0.74) | 3.37(0.75) | |

| Cesarean section | 3.28 (0.67) | 3.27 (0.70) | |

| P value b | <.001 | <.001 |

Data are given as mean (SD). Minimum value = 1, maximum value = 4.

Mann‐Whitney U test, P value between high‐dose group and low‐dose group.

Kruskal‐Wallis test, P value comparing spontaneous vaginal birth, instrumental vaginal birth and cesarean section.

In comparisons between groups with different modes of birth (spontaneous vaginal birth, instrumental vaginal birth and cesarean section), women with spontaneous vaginal birth had significantly higher mean scores in all four subscales, compared with instrumental vaginal birth and emergency cesarean (Table 2). Additionally, when comparing childbirth experiences between the groups of women with spontaneous vaginal birth and operative birth (instrumental vaginal birth and cesarean section), the group of women with spontaneous vaginal birth scored significantly higher in all four subscales (data not shown).

There was no difference in reported labor pain between high‐ vs low‐dose oxytocin, reported either 2 hours postpartum (mean score 65.9 in high dose [n = 329] vs 67.5 in low dose [n = 346]; P = .67) or 1 month after birth (mean score 73.4 in high dose [n = 497] vs 71.7 in low dose [n = 511]; P = .25). Women who reported labor pain at both occasions (n = 565) reported a significantly higher mean score of experienced pain 1 month after birth compared with 2 hours postpartum (mean score 73.1 vs 66.9; P = .012).

4. DISCUSSION

In a parallel, double‐blind RCT, primiparous women with delayed labor progress received a high‐dose vs a low‐dose of oxytocin for augmentation. In this report of the RCT, we compared women’s childbirth experiences measured with the CEQ2 and the experience of labor pain in the two oxytocin dose groups.

The analysis showed that childbirth experience measured by the CEQ2, did not differ significantly between the two groups of women in the four domains Own capacity, Perceived safety, Professional support, and Participation, with a defined delayed labor progress receiving either a high dose of oxytocin or a low dose of oxytocin. Furthermore, no difference in reported labor pain was found between the two oxytocin groups, at either 2 hours postpartum at the labor ward or 1 month after birth.

Both the first version CEQ and its revised form CEQ2 have shown good measurement qualities and ability to distinguish between known groups (eg those with instrumental births, those in labor in excess of 12 hours and those who had their labors augmented with oxytocin). 21 , 23 The high quality in terms of validity and reliability of the first version (CEQ) has been identified in a systematic review of existing questionnaires measuring women’s childbirth experiences, and it has been suggested for use in identifying women with negative experiences of childbirth and for evaluating quality of care. 24 In this study, all four domains of the CEQ2 showed good reliability. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were high in all four domains.

The study has several strengths. With the RCT design, the risk for bias and skewed distribution of confounders was reduced. The large number of included women and the high response rate among these women also reduced the risk for bias in results.

A weakness of the study was the low response rate postpartum at the labor ward, according to self‐reported experienced pain during labor. Just over half of the women were asked by their midwife in charge to evaluate their experience of pain during labor, a situation that might reflect a heavy workload at the labor ward. A further weakness of the study was that the questionnaire was not sent to those of the randomized women who did not receive oxytocin for augmentation but who were included in the original study in an intention‐to‐treat analysis. Furthermore, the high‐dose regimen was changed to a standard regimen (equivalent to a low‐dose regimen) after 1000 mL; however, this was done only in nine women, and we therefore do not think that this has affected the results.

There is little research regarding experience of childbirth and dosage of oxytocin, but in an early study of the package of active management of labor, a high dose of oxytocin for augmentation together with an early intervention was compared with a low dose of oxytocin together with a more expectant intervention. No differences were seen in women’s satisfaction with labor between the two groups. 25 , 26 Effects of early or expectant oxytocin augmentation on different aspects of the childbirth experience have been investigated as a single agent and have shown similar results. 12 , 16 , 27 Our findings for the domains, when comparing high dose vs low dose of oxytocin, were consistent with the pilot study of Kenyon, where no differences in perception of support and control were seen between the dosage groups. 18 The dose of oxytocin in our RCT was titrated according to perceived and registered adequacy of uterine contractions. Results from the first report of the RCT showed that women in the high‐dose group received an increased total amount of oxytocin and a higher amount of oxytocin per minute compared with women in the low‐dose group with little or no effect on the progress of labor, indicating that the titration process is imprecise and the response to oxytocin is very much individual. 19 Additionally, more episodes of uterine tachysystole occurred, and oxytocin infusion was stopped or reduced temporarily due to uterine tachysystole together with suspicious or pathological fetal heart rate pattern more often than in the low‐dose group. 19 Neither of these findings seemed to have an impact on childbirth experiences in the randomized groups with different oxytocin dosage.

Almost all of the women (99%) participating in our study suffered from a delayed labor progress with an increased risk for an adverse outcome, including a negative childbirth experience. 28 Management of a delayed progress includes medical and technological interventions, such as augmentation with oxytocin together with continuous monitoring of both mother and child, factors that can influence the woman’s choices with regard to mobility and pain relief options. Furthermore, with the occurrence of a delayed progress, the control of the birthing process is shifted from the woman to her caregivers. When comparing the four domains Own capacity, Perceived safety, Professional support and Participation in our study, the lowest mean score was found in Own capacity. This domain included items regarding sense of control, personal feelings during childbirth and labor pain. According to earlier findings, the degree of choice and control is an important factor for how birth will be experienced. 29 Women want to be in control of their birthing process 30 and our result may reflect women’s feelings when the birthing progress is taken over by caregivers. Women with a delayed labor, with the risk of feelings of losing control during labor, are therefore in special need of extra support, an important factor to consider when planning care on the labor ward. 11 , 28

Additionally, with a delayed labor progress associated with pain, women are more vulnerable to having a negative birth experience. 28 Women in our study scored experienced greater labor pain 1 month after birth higher than postpartum after birth; however, the result should be interpreted with caution, if it has any clinical importance, due to a small mean score difference (6.1) together with the low response rate of postpartum pain assessment. The use of epidural analgesia as pain relief during labor was high in both the high‐dose and the low‐dose group (86.9% and 85.7%, respectively). Despite this, experienced labor pain was reported as high, with mean scores of 73.4 and 71.7, respectively, 1 month after birth.

The high incidence of cesarean section among primiparous women and its association with a delayed labor progress is of major concern in childbirth care. 31 , 32 Women in our study with an adverse labor outcome of emergency cesarean or instrumental vaginal birth scored lower than women with a spontaneous vaginal birth in all subdomains and in both dosage groups. This result corresponds well with earlier findings on mode of birth and its impact on a birth experience, where both cesarean section and instrumental vaginal birth have been associated with a negative birth experience. 2 , 10 , 33

5. CONCLUSION

According to our study, women’s experience of childbirth is not affected by the dosage of oxytocin given for augmentation of a delayed labor. Considering the lack of advantages for mother and child using a high dose of oxytocin, use of low‐dose oxytocin is preferable to avoid unnecessary events of tachysystole and fetal distress.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Supporting information

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the study midwives Pia Vikner, Madelen Jakobsson, Lena Rehnberg Brandt, Veronica Miranda‐Lemner, Maria Norrbäck, Anna Woxenius and Caroline Lindvall. We also wish to acknowledge the assistance given by Erik Sturén in the statistical analyses and Arvid Birkenmeier in the development of the computer‐generated CEQ2.

Selin L, Berg M, Wennerholm U‐B, Dencker A. Dosage of oxytocin for augmentation of labor and women’s childbirth experiences: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:971–978. 10.1111/aogs.14042

Funding information

The Swedish Medical Research Council; the Department of Research and Development, NU‐Hospital Group, Sweden; the Fyrbodal Research and Development Council, Region Västra Götaland, Sweden; the Health & Medical Care Committee of the Regional Executive Board, Region Västra Götaland, Sweden. Some of the coordinating centers funded midwifery time for the trial.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lundgren I. Swedish women’s experience of childbirth 2 years after birth. Midwifery. 2005;21:346‐354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Waldenstrom U, Hildingsson I, Rubertsson C, Radestad I. A negative birth experience: prevalence and risk factors in a national sample. Birth. 2004;31:17‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ayers S, Bond R, Bertullies S, Wijma K. The aetiology of post‐traumatic stress following childbirth: a meta‐analysis and theoretical framework. Psychol Med. 2016;46:1121‐1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dencker A, Nilsson C, Begley C, et al. Causes and outcomes in studies of fear of childbirth: a systematic review. Women Birth. 2019;32:99‐111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shorey S, Yang YY, Ang E. The impact of negative childbirth experience on future reproductive decisions: a quantitative systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:1236‐1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Waldenstrom U, Schytt E. A longitudinal study of women’s memory of labour pain – from 2 months to 5 years after the birth. BJOG. 2009;116:577‐583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Selin L, Wallin G, Berg M. Dystocia in labour – risk factors, management and outcome: a retrospective observational study in a Swedish setting. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:216‐221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kjaergaard H, Olsen J, Ottesen B, Dykes AK. Incidence and outcomes of dystocia in the active phase of labor in term nulliparous women with spontaneous labor onset. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:402‐407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nystedt A, Hildingsson I. Women’s and men’s negative experience of child birth‐A cross‐sectional survey. Women Birth. 2018;31:103‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hildingsson I, Karlström A, Nystedt A. Parents’ experiences of an instrumental vaginal birth findings from a regional survey in Sweden. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2013;4:3‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kjaergaard H, Foldgast AM, Dykes AK. Experiences of non‐progressive and augmented labour among nulliparous women: a qualitative interview study in a Grounded Theory approach. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bergqvist L, Dencker A, Taft C, et al. Women’s experiences after early versus postponed oxytocin treatment of slow progress in first childbirth – a randomized controlled trial. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2012;3:61‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bugg GJ, Siddiqui F, Thornton JG. Oxytocin versus no treatment or delayed treatment for slow progress in the first stage of spontaneous labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD007123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blanch G, Lavender T, Walkinshaw S, Alfirevic Z. Dysfunctional labour: a randomised trial. BJOG. 1998;105:117‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lavender T, Wallymahmed AH, Walkinshaw SA. Managing labor using partograms with different action lines: a prospective study of women’s views. Birth. 1999;26:89‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lavender T, Alfirevic Z, Walkinshaw S. Effect of different partogram action lines on birth outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:295‐302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kenyon S, Tokumasu H, Dowswell T, Pledge D, Mori R. High‐dose versus low‐dose oxytocin for augmentation of delayed labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(7):CD007201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kenyon S, Armstrong N, Johnston T, et al. Standard‐ or high‐dose oxytocin for nulliparous women with confirmed delay in labour: quantitative and qualitative results from a pilot randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2013;120:1403‐1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Selin L, Wennerholm U‐B, Jonsson M, et al. High‐dose versus low‐dose of oxytocin for labour augmentation: a randomised controlled trial. Women Birth. 2019;32:356‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berg M, Dykes AK, Nordström L, Wennerholm U‐B. Indikation för värkstimulering med oxytocin under aktiv förlossning. Göteborg; 2011. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint‐dokument/dokument‐webb/ovrigt/nationella‐indikationer‐varkstimulering‐oxytocin.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2020.

- 21. Dencker A, Bergqvist L, Berg M, Greenbrook JTV, Nilsson C, Lundgren I. Measuring women’s experiences of decision‐making and aspects of midwifery support: a confirmatory factor analysis of the revised Childbirth Experience Questionnaire. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Walker KF, Dencker A, Thornton JG. Childbirth experience questionnaire 2: validating its use in the United Kingdom. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X. 2019;5:100097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dencker A, Taft C, Bergqvist L, Lilja H, Berg M. Childbirth experience questionnaire (CEQ): development and evaluation of a multidimensional instrument. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nilver H, Begley C, Berg M. Measuring women’s childbirth experiences: a systematic review for identification and analysis of validated instruments. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sadler LC, Davison T, McCowan LM. Maternal satisfaction with active management of labor: a randomized controlled trial. Birth. 2001;28:225‐235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sadler LC, Davison T, McCowan LM. A randomised controlled trial and meta‐analysis of active management of labour. BJOG. 2000;107:909‐915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hinshaw K, Simpson S, Cummings S, Hildreth A, Thornton J. A randomised controlled trial of early versus delayed oxytocin augmentation to treat primary dysfunctional labour in nulliparous women. BJOG. 2008;115(10):1289‐1295; discussion 95‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nystedt A, Hogberg U, Lundman B. Some Swedish women’s experiences of prolonged labour. Midwifery. 2006;22:56‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cook K, Loomis C. The impact of choice and control on women’s childbirth experiences. J Perinat Educ. 2012;21:158‐168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. WHO. Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/intrapartum‐care‐guidelines/en/. Accessed April 22, 2018. [PubMed]

- 31. Ressel GW. ACOG releases report on dystocia and augmentation of labor. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1290, 1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haerskjold A, Hegaard HK, Kjaergaard H. Emergency caesarean section in low risk nulliparous women. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32:543‐547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ryding EL, Wijma K, Wijma B. Experiences of emergency cesarean section: a phenomenological study of 53 women. Birth. 1998;25:246‐251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1