Abstract

Heterogeneity of leukemia stem cells (LSCs) is involved in their collective chemoresistance. To eradicate LSCs, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms underlying their heterogeneity. Here, we aimed to identify signals responsible for heterogeneity and variation of LSCs in human acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Monitoring expression levels of endothelial cell‐selective adhesion molecule (ESAM), a hematopoietic stem cell‐related marker, was useful to detect the plasticity of AML cells. While healthy human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells robustly expressed ESAM, AML cells exhibited heterogeneous ESAM expression. Interestingly, ESAM− and ESAM+ leukemia cells obtained from AML patients were mutually interconvertible in culture. KG1a and CMK, human AML clones, also represented the heterogeneity in terms of ESAM expression. Single cell culture with ESAM− or ESAM+ AML clones recapitulated the phenotypic interconversion. The phenotypic alteration was regulated at the gene expression level, and RNA sequencing revealed activation of TGFβ signaling in these cells. AML cells secreted TGFβ1, which autonomously activated TGFβ pathway and induced their phenotypic variation. Surprisingly, TGFβ signaling blockade inhibited not only the variation but also the proliferation of AML cells. Therefore, autonomous activation of TGFβ signaling underlies the LSC heterogeneity, which may be a promising therapeutic target for AML.

Keywords: acute myeloid leukemia, autonomous signaling, chemoresistance, endothelial cell‐selective adhesion molecule, heterogeneity, leukemia stem cells, phenotypic variation, TGFβ

Leukemic stem cells (LSCs) in human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) represent phenotypic variability, which is delineated by endothelial cell‐selective adhesion molecule (ESAM) expression. The variable ESAM levels reflect fluctuating transcriptome in LSCs that is at least partly regulated by autocrine/paracrine cytokine signals. While autonomous TGFβ1 signaling promotes the phenotypic variability of LSCs, blocking the signaling inhibits not only their variability but also their growth by inducing apoptosis.

Significance statement.

The authors have shown the autonomous TGFβ signaling as one of the molecular mechanisms underlying heterogeneity and variability of leukemia stem cells associated with human acute myeloid leukemia (AML). By monitoring the endothelial cell‐selective adhesion molecule (ESAM) expression, the authors found that human AML cells were phenotypically heterogeneous and variable. ESAM− and ESAM+ AML cells were mutually convertible in culture. The authors determined that autocrine TGFβ signaling was involved in AML cell heterogeneity and variability. Inhibiting the TGFβ pathway not only suppressed ESAM variability, but also induced AML cell apoptosis. Thus, mechanisms promoting the heterogeneity and variability of LSCs can be therapeutic targets against intractable AML.

1. INTRODUCTION

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) has attracted increasing attention since it explains why several cancer patients experience relapse even after intensive treatment 1 , 2 . If a small subset of cancer cells inherently resistant to chemoradiotherapies remained and survived after therapeutic intervention, these would eventually lead to recurrence. 3 , 4 Although treatment‐resistant cells are not involved in initiating tumorigenesis, they are widely recognized as CSCs, which are critical in cancer treatment and clinical outcome. To eradicate CSCs, it is important to understand their features. Accumulating studies on CSCs, however, have shed light on their challenging complexities, including their heterogeneity. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8

Transplantation of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells into severe combined immune‐deficient (SCID) mice allowed the first identification of CSCs involved in human diseases. 9 While the earliest studies determined the phenotype of stem cells in AML, namely leukemia stem cells (LSCs), as CD34+CD38−, subsequent studies with improved xenograft models proved that LSCs are phenotypically heterogeneous, and reside in other fractions such as CD34+CD38+ or even in the CD34− fraction. 10 , 11 In addition, Goardon et al. reported that two distinct but hierarchically related LSC populations coexist in most patients with AML. 12 , 13 One LSC population shows immature phenotype with CD34+CD38−CD45RA+, which is identical to lymphoid‐primed multipotent progenitors in normal hematopoietic differentiation, whereas the other expresses CD34, CD38, CD45RA, and CD123/IL‐3Ra, which resembles granulocyte‐macrophage progenitors. The former LSC population giving rise to the latter, but not vice versa, demonstrates the hierarchy in LSCs, which mirror normal hematopoietic process. However, other studies showed that LSC activity is detectable even in lineage marker (Lin)‐expressing cells, which reconstitute the original AML profile (including the primitive Lin− CD34+CD38− fraction) after xenotransplantation to immunodeficient mice. 14 Collectively, these results demonstrate that LSCs in AML are essentially heterogeneous and cannot be defined solely by the cell surface phenotype. While the diverse LSCs may originate in different stages and construct the hierarchy, LSCs may also undergo dedifferentiation or interconversion, which is observed in CSCs of other cancers, such as melanoma, skin squamous cell carcinoma, and pancreas cancer. 1 , 15 , 16 , 17 The development of efficient strategies to eradicate LSCs would require understanding the precise molecular mechanisms that underlie LSC heterogeneity.

We have previously found that endothelial‐cell selective adhesion molecule (ESAM) is useful to isolate hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in mice and human. 18 , 19 As LSC activity is enriched according to ESAM expression, ESAM could also be considered a useful marker of LSCs in human AML. Indeed, after xenotransplantation, KG1a cells expressing ESAM promote more aggressive tumor growth than those not expressing ESAM. Interestingly, ESAM− KG1a cells also produce leukemic tumors in xenografts at a slower pace, in which numerous ESAM‐expressing leukemia cells are recovered. These observations suggest that unraveling the molecular mechanisms regulating ESAM expression on AML cells may better explain the mechanisms underlaying LSC heterogeneity. In this study, we monitored ESAM expression levels of primary human AML samples and investigated the mechanisms regulating the heterogeneity of LSCs. Our results revealed an unexpected mechanism inherent to LSCs in AML.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Human samples

BM samples from patients with AML at diagnosis or relapse were obtained after receiving written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Osaka University Hospital (no. 13167).

2.2. Cell lines

KG1a (CVCL_1824) was purchased from ATCC and used in this study. CMK (CVCL_0216) was provided from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Cell lines were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 and maintained in RPMI 1640 (Nacalai Tesque) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S, Nacalai Tesque). In some experiments, recombinant human TGF‐β1(Biolegend) or was added to culture medium.

2.3. Flow cytometry analysis and cell sorting

Antibodies used in this study are shown in Table S1. Human ESAM Antibody was biotinylated using EZ‐Link Sulfo‐NHS‐Biotin and biotinylation kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. APC Streptavidin was used for visualization of biotinylated antibody. Dead cells were excluded by staining with 7‐aminoactinomycin D (7‐AAD, Calbiochem). Cells were washed and then resuspended in PBS− containing 3% FBS (MP Biomedicals). Cells were analyzed using FACSAria IIIu (BD Biosciences). In some cases, ESAM− or ESAM+ cells were sorted using FACSAria IIIu before use in subsequent experiments. FACS data was analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo, LLC).

2.4. Primary leukemia cell culture

Primary leukemia cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in MEMα (Gibco) containing 10% FBS and 1% P/S, in the presence of recombinant human SCF (10 ng/mL, Biolegend), recombinant human Flt3‐ligand (100 ng/mL, Biolegend), and recombinant human TPO (100 ng/mL, Biolegend).

2.5. Real time RT‐PCR

Total RNA was extracted with PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A High Capacity RNA‐to‐cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems) was used for cDNA synthesis. Real time RT‐PCR was performed on an ABI PRISM 7900 HT (Applied Biosystems, Inc). Expression levels were normalized to those of the internal reference β‐actin. Primers used in this study are shown in Table S2.

2.6. ELISA

KG1a were cultured in SF‐03(Sekisui medical) medium for 3 days. Then, the supernatant was collected and TGFβ1 concentration was measured with LEGEND MAX Total TGF‐β1 ELISA Kit (Biolegend) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.7. Apoptosis assay

KG1a cells or primary AML cells were cultured with SB525334(CAS356559‐20‐1, Calbiochem) and daunorubicin hydrochloride (CAS23541‐50‐6, Sigma‐Aldrich). DMSO was added to control samples without SB525334. Subsequently, cells were resuspended in Annexin V Binding Buffer (BD Pharmingen) and stained with FITC‐Annexin V and 7‐AAD. Stained cells were analyzed using FACSAria IIIu.

2.8. RNA‐sequencing analysis

KG1a CD34+CD38− ESAM‐Neg or CD34+CD38− ESAM‐Hi cells were sorted using flow cytometry, and their total RNA was extracted with RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Library preparation was performed using a TruSeq stranded mRNA sample prep kit (Illumina) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform in a 75‐base single‐end mode. Illumina Casava1.8.2 software used for basecalling. Sequenced reads were mapped to the human reference genome sequences (hg19) using TopHat v2.0.13 in combination with Bowtie2 ver. 2.2.3 and SAMtools ver. 0.1.19. The number of fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments (FPKMs) was calculated using Cuffnorm ver. 2.2.1. Access to raw data from this study was submitted under Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) accession number GSE150081. The datasets were analyzed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis(Qiagen).

2.9. Immunoblotting assay

Total cell lysate was prepared in lysis buffer [10 mM Tris‐HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% TritonX‐100,1 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP‐40 and protease inhibitor cocktail (Nacalai Tesque)]. Cell lysates (5‐10 μg total protein per lane) were separated using a 4‐12% NuPAGE gel system (Invitrogen) under reducing conditions and immunoblotted using appropriate antibodies (Table S1). Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI‐COR Biotechnology).

2.10. Statistical analysis

Student's t‐tests were used to compare data between two groups. Statistical analyses were conducted using error bars to represent SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism7(GraphPad). Results with P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Human AML cells are heterogeneous in terms of ESAM expression levels

Our previous study identified that a subset of human acute leukemia cell lines, particularly erythroid and megakaryocyte lines, express ESAM. 19 Therefore, we initially evaluated ESAM expression levels in primary BM specimens from human acute leukemia patients (Figure S1A). Flow cytometry analyses showed that 12 out of 21 AML cases expressed ESAM on the leukemia cell‐enriched fraction at a frequency higher than 20%, whereas none of the ALL cases expressed ESAM. Several reports demonstrated that, among leukemic cells, LSCs in human AML are enriched in the CD34+CD38− fraction. 9 , 11 , 12 , 20 , 21 Although LSC activity is also observed in the CD34+CD38+ and CD34− fractions, the CD34+CD38− population often exhibits higher LSC frequencies compared with the other two fractions. 11 To determine whether ESAM can enrich LSCs, we evaluated the frequencies of ESAM‐expressing leukemia cells in the three fractions of individual patients with AML. We found that the frequency of ESAM+ cells was significantly higher in the CD34+CD38− fraction, but decreased with CD38 expression and CD34 disappearance (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Human AML cells are heterogeneous in terms of ESAM expression levels. ESAM expression in clinical samples of AML (n = 21) and ALL (n = 6). Mononuclear cells (MNCs) from BM of leukemia patients were stained with antibodies against CD45, CD34, CD38, and ESAM and analyzed using flow cytometry. Leukemia cell fraction was extracted by FSC and SSC gate of flow cytometry. Dead cells were removed with 7‐AAD. A, ESAM positive rate in CD34+CD38−, CD34+CD38+, and CD34−CD38+ fractions in leukemia cells of each AML sample (n = 21). B, Expression of ESAM and CD45 in each sample in CD34+CD38− fraction. M1, M2, and so forth indicate FAB classification of leukemia. Percentages of cells in each gate are indicated in each panel. Data are shown as means ± SEMs. Statistically significant differences are represented by asterisks (**P < .01, ***P < .001)

Notably, however, ESAM expression pattern remarkably differed among AML patients (Figures 1B and S1B). Indeed, ESAM expression was negative or very low in the CD34+CD38− fraction of some patients with AML, which is aberrant because more than 80% of normal CD34+CD38− cells express ESAM. 19 Furthermore, ESAM expression was apparently heterogeneous in most of AML cases (Figure S1B). These results suggest that ESAM expression might mark LSCs in a subset of AML cases, but there is intrinsic heterogeneity among patients and even within an individual case.

3.2. AML LSCs present phenotypical variability of ESAM expression

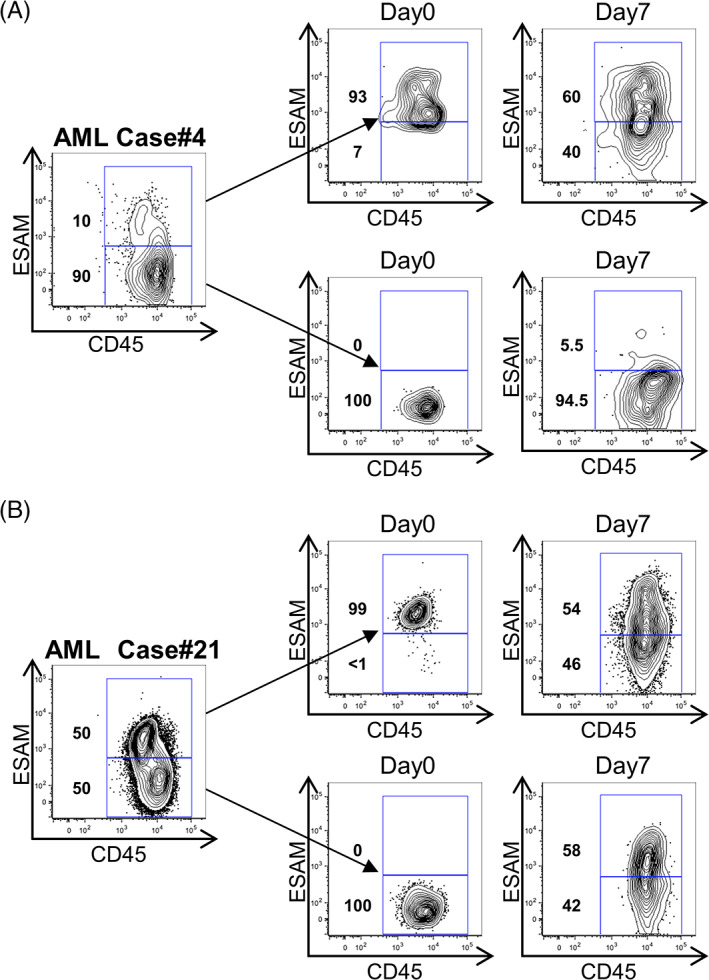

While some studies showed a hierarchical relationship between AML LSCs in the CD34+CD38− and CD34+CD38+ fractions, 12 reversible variability between LSCs with different phenotypes has also been reported. 14 This issue is important to determine the clonal origin of LSCs in individual patients with AML. To address this, we divided CD34+ cells of primary AML into ESAM− and ESAM+ fractions, and tested their interconversion in culture. In this experiment, we selected two AML cases whose CD34+ fractions consisted of ESAM− and ESAM+ cell populations (Figure 2). As shown in Figure 2A, CD34+ESAM+ cells from AML case #4 generated CD34+ESAM− cells along a hierarchical order, although a subtle but detectable reversibility was observed. Additionally, in AML case #21, both ESAM+ and ESAM− populations gave rise to the other robustly. These results were consistent with previous observations, 14 in which a hierarchical relationship between LSCs existed in some AML cases, while phenotypical variability between LSCs was generally present, to a varying degree. In our previous study, we observed that normal CD34+ESAM− cells obtained from human cord blood were devoid of the HSC capability, that is, the long‐term reconstituting potential. 19 Additionally, those CD34+ESAM− cells generated no CD34+ESAM+ population in vitro or in vivo, suggesting that the phenotypic plasticity is likely to be more related to LSCs than normal HSCs.

FIGURE 2.

AML LSCs present phenotypical variability of ESAM expression. A and B, ESAM+ and ESAM− cells of the CD34+ fraction of primary AML cells were sorted and cultured in MEMα containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S), in the presence of stem cell factor (10 ng/mL), Flt3 ligand (100 ng/mL), and thrombopoietin (100 ng/mL). The medium was changed on day 4 and cells were then cultured for 7 days. ESAM and CD45 expression before sorting (left), at the time of sorting (middle, day 0), and after culture (right, day 7) are shown. Percentages of cells in each gate are indicated in each panel

3.3. Clonal AML LSCs represent the variability according to ESAM expression

Next, we assessed whether the phenotypical variability in LSCs occurred at the clonal level. To this end, we exploited human AML cell lines as a clonal LSC model. In our previous study, KG1a cells maintained in our lab for long periods were found to be negative for ESAM expression. 19 However, they became ESAM‐positive and acquired more aggressive leukemic activity after propagated in vivo. 19 Given the possibility that KG1a cells might have changed their phenotype during the repeated in vitro passage, we newly purchased original KG1a cells from ATCC and used in this study.

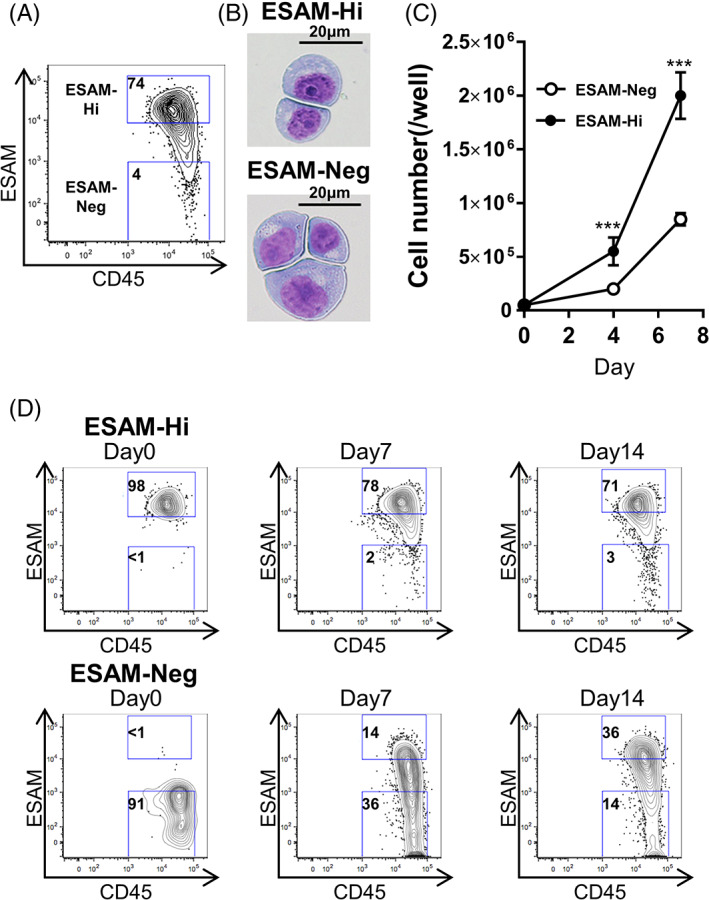

Among the tested cell lines, the original KG1a and CMK showed a broad distribution of ESAM levels (Figures 3A and S2A). KG1a cells showed exclusively immature CD34+CD38− phenotype, and displayed wide‐ranging ESAM expression (Figure 3A). We sorted two subpopulations with the highest and lowest ESAM expression (henceforth denoted as ESAM‐Hi and ESAM‐Neg). Compared with ESAM‐Hi cells, ESAM‐Neg cells were characterized with abundant cytoplasm, conspicuous perinuclear halo, and fine chromatin structure (Figure 3B). When we cultured the two cell populations in standard growth medium, we observed marked differences in growth rate between them (Figure 3C). However, each population recreated a heterogeneous ESAM expression profile similar to that of the parental population (Figure 3D). The same result was obtained with CMK cells (Figure S2B). Restoration of the original parental profile was also observed using re‐sorted ESAM‐Hi and ESAM‐Neg cells (Figure S2C). Collectively, these results indicate that AML LSCs are heterogeneous even in the genetically same clone.

FIGURE 3.

AML cell lines present phenotypical variability of ESAM expression. Human acute myelogenous line KG1a was stained with antibodies against CD45, CD34, CD38, and ESAM and analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of cells in each gate are shown in each panel. A, ESAM and CD45 expression in CD34+CD38− fraction of KG1a. B, ESAM‐Neg and ESAM‐Hi CD34+CD38− fraction of KG1a were sorted, and the cytospin slides were stained with May Grunwald/Giemsa staining. Horizontal bars represent 20 μm. C, Continuous culture of ESAM‐Neg or ESAM‐Hi CD34+CD38−KG1a cells (n = 3). Cell counts on days 4 and 7. D, ESAM‐Neg and ESAM‐Hi cells of the CD34+CD38− fraction of KG1a cells were sorted and cultured for 35 days. Culture medium was changed twice a week. ESAM and CD45 expression at the time of sorting and on day 7, 14, and 35 are shown. Percentages of cells in each gate are indicated in each panel. Data are shown as means ± SEMs. Statistically significant differences are represented by asterisks (***P < .001)

3.4. Single LSCs reconstitute heterogeneity

Even within highly enriched populations, traces of contaminants may affect the experimental results. Moreover, a few outlier cells in a clonal population might have robust proliferating and fluctuating characteristics, to which we could attribute the observed variability. To exclude these possibilities, we determined whether individual cells would reconstitute the parental profile of heterogeneous ESAM expression.

Cells of the ESAM‐Neg or ESAM‐Hi fraction were single‐sorted into 96‐well plates and cultured for 28 days under periodic microscopic observation. Both fractions contained a number of single cells with growth potential. As shown in Figure 4 with four representative cells, single cells in both fractions unsurprisingly restored heterogeneous populations with a wide spectrum of ESAM levels. Indeed, even a cell with low initial ESAM expression level produced a robust ESAM+ population (Figure 4B upper). These results implicate that the variability in LSCs is not due to some aberrant clones but probably to the inherent nature of each individual LSC.

FIGURE 4.

Single LSCs reconstitute heterogeneity. Cells of the ESAM‐Neg or ESAM‐Hi fraction were single‐sorted into 96‐well plates and cultured for 28 days under periodic microscopic observation. A and B, Antigen analysis of cells that formed colonies on day 28 after single‐cell sorting. ESAM and CD45 at the time of sorting (left) and on day 28 (right) are shown. Percentages of cells in each gate are indicated in each panel

3.5. LSC heterogeneity is regulated at the gene expression level

To unveil what mechanism underlies the restoration of parental ESAM distribution from diverse LSCs, we next evaluated the amount of ESAM transcripts in ESAM‐Neg and ESAM‐Hi fractions sorted from parent KG1a cells. Real time RT‐PCR examination revealed marked differences in ESAM mRNA levels between the two fractions (Figure 5A). Furthermore, recovered ESAM‐Neg and ESAM‐Hi fractions from single cells also presented clear differences in ESAM mRNA expression, in accordance with the levels of ESAM at the time of sorting on their surface (Figure 5B). These results suggest that the changes in ESAM expression occur at the transcriptional level.

FIGURE 5.

LSC heterogeneity is regulated at the gene expression level. A, ESAM mRNA levels analyzed using real time RT‐PCR (n = 5). B, ESAM mRNA levels after single‐cell culture analyzed using real time RT‐PCR (n = 3). Single cell with ESAM‐Neg or ESAM‐Hi of CD34+CD38−fraction of KG1a was sorted and cultured for 28 days. ESAM‐Neg and ESAM‐Hi fraction cells were sorted again from the clones after culturing. C, Gene expression profiles of CD34+CD38− cells between ESAM‐Neg and ESAM‐Hi were compared through RNA sequencing analysis. Scatterplots comparing transcript levels (in fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments) in ESAM‐Neg (x‐axis) and ‐Hi (y‐axis). D, Regulator network analyses. The significantly altered networks are shown. E, Upstream regulator analyses. The significantly altered upstream regulators are shown. Pathways with P‐values below 10−12 were extracted and arranged in descending order of z‐value. Data are shown as means ± SEMs. Statistically significant differences are represented by asterisks (***P < .001)

To examine whether the phenotypic variation was caused by random fluctuation of the sole ESAM gene, we conducted RNA sequencing on ESAM‐Hi and ESAM‐Neg KG1a fractions immediately after sorting. This analysis revealed that the two fractions essentially differed in their transcriptomes, with 1186 genes showing significantly different expression (Figure 5C). Among the genes with the highest differences, IL1RL1, ITGA2B, and CHRM3 had over 60‐fold higher expression in the ESAM‐Hi fraction than in ESAM‐Neg (Figure S3A). These genes encode cell surface receptors for IL33, fibrinogen/fibronectin/vitronectin, and muscarinic acetylcholine, respectively. Several genes encoding functional proteins were also upregulated in the ESAM‐Neg fraction. Interestingly, these included KLRC1, RGS1, ITGB7, and BCL6, whose roles are intimately related to the lymphoid lineage. Real‐time RT‐PCR analysis confirmed the results of RNA sequencing (Figure S3B). Differences in ITGB7 expression levels between ESAM‐Hi and ESAM‐Neg showed reverse trend to that of ESAM expression even after serial sorting (Figure S3C). Transcriptome variability, along with changes in ESAM expression, was also observed in CMK, another AML cell line. However, the change pattern in CMK cells was found to essentially differ from that in KG1a cells (Figure S3D). That is, the fluctuation of ITGB7 and KLRC1 expression in CMK cells showed a similar pattern to that in KG1a cells, whereas that of ITGA2B, TIM3, and BCL6 showed an opposite pattern. These observations illustrate the robust transcriptome variability underlying the biological differences among different AML clones. Furthermore, functional diversity may exist even in a single AML clone, which can be reflected by the variation in ESAM expression levels.

Regulatory network analysis using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software revealed that “maturation of blood cells” is the network most affected by the difference in ESAM expression levels (Figure 5D). A detailed network analysis also uncovered that the genes related to cell maturation were mostly inhibited in the ESAM‐Hi fraction (Figure S4). These results point to a hierarchical order among AML LSCs from ESAM‐Hi to ESAM‐Neg, which reflects normal hematopoiesis. Collectively, while the ESAM‐Neg fraction exhibited a differentiation‐prone transcriptome, this feature is not irreversibly fixed, while some ESAM‐Neg cells could reverse to immature stages. This finding supports the observation made in primary AML cells (Figure 2) and the notion that the differentiation hierarchy and the variability in AML LSCs are not mutually exclusive.

3.6. Autonomous TGFβ1 signaling promotes phenotypic variability of LSC

To elucidate the mechanisms underlaying the transcriptome variability regulation in LSCs, we performed upstream analysis of RNA sequencing data. This approach helped us identify several cytokine‐signaling pathways that could be responsible for the transcriptome differences between ESAM‐Neg and ESAM‐Hi. Among the identified pathways, most inflammatory cytokine signals such as TNFα and IFNα had negative z‐value, meaning that they were active in ESAM‐Neg. On the other hand, only the TGFβ signaling showed positive z‐value, suggesting its activation in ESAM‐Hi (Figure 5E).

Higher phosphorylation levels of Smad2/3 were detected in ESAM‐Hi, which indicates the activation of TGFβ signaling (Figure S5). Additionally, the amount of TGFB1 transcripts was substantive in KG1a cells whereas no transcripts for TNFA or IFNA were detected (as shown by the RNA‐sequence results). This suggests that TGFβ may be more directly involved in the transcriptome signature of ESAM‐Hi cells.

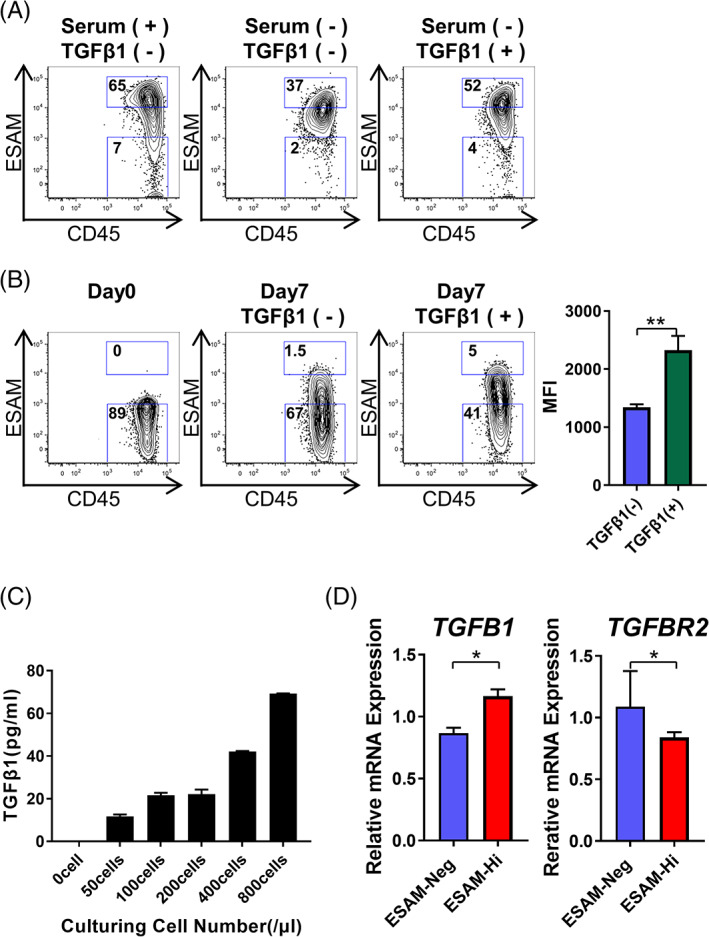

As the standard growth medium for KG1a cells with 10% FBS contains natural TGFβ1 at approximately 1 ng/mL, we analyzed how the expression of ESAM would change in the absence of FBS. When cultured in serum‐free condition, the entire cell population homogeneously converged to an ESAM‐intermediate stage (Figure 6A middle). However, adding 1 ng/mL TGFβ1 to the serum‐free medium restored the heterogeneous ESAM expression (Figure 6A right). These results support the findings from the upstream analysis, suggesting that TGFβ1 is involved in the regulation of ESAM expression. Next, we analyzed how TGFβ1 influences ESAM expression of ESAM‐Neg cells. When TGFβ1 was added to the medium, the mean expression intensity of ESAM significantly increased in sorted ESAM‐Neg cells, suggesting that TGFβ1 signaling upregulated ESAM levels in these cells (Figure 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Autonomous TGFβ1 signaling promotes phenotypic variability of LSC. A, KG1a were cultured in SF‐03 (serum‐free medium) with or without recombinant TGFβ1 (1 ng/mL). Medium was changed on day 3, and cells were cultured for 7 days. Shown is expression of ESAM and CD45 after culture (n = 3). B, ESAM‐Neg cells of the CD34+CD38− fraction of KG1a were sorted and cultured for 7 days with or without recombinant TGFβ1 (10 ng/mL). ESAM and CD45 expression at the time of sorting (left), on day 14 without TGFβ1 (middle), and day 7 with TGFβ1 (right) are shown (n = 3). Percentages of cells in each gate are indicated in each panel. C, KG1a were cultured in serum‐free medium for 3 days with varying cell numbers (n = 3). Then, the supernatant was collected and TGFβ1 concentration was measured by ELISA. D, TGFB1 and TGFBR2 mRNA levels analyzed using real time RT‐PCR (n = 3). Data are shown as means ± SEMs. Statistically significant differences are represented by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001)

KG1a cells restore their phenotypic heterogeneity even in serum‐free conditions in the long term (data not shown). From this observation, we inferred that autocrine/paracrine TGFβ1 might be involved in the phenotypic variability of LSCs. In fact, after culturing KG1a in serum‐free medium, TGFβ1 concentration in the culture supernatant increased in a cell‐number dependent manner (Figure 6C). Furthermore, real‐time RT‐PCR showed that ESAM‐Hi expressed higher levels of TGFB1 than ESAM‐Neg (Figure 6D left). Interestingly, the expression of TGFBR2, of which levels are known to correlate with the activation of TGFβ signaling pathway, 22 showed a reciprocal change (Figure 6D right).

3.7. Blocking TGFβ signaling induces cell death of leukemia cells

Our ultimate goal is to identify efficient therapeutic strategies to eradicate AML LSCs. Based on the results described above, AML LSCs are fluctuating in terms of transcriptomes as well as surface phenotypes, due at least in part to autocrine/paracrine TGFβ1, which we presumed may be involved in treatment resistance. Therefore, we examined whether inhibiting TGFβ signaling would block the fluctuations and enhance the chemosensitivity of AML cells. To this aim, we added SB525334 (TGFβRI Kinase Inhibitor VIII), a selective TGFβRI inhibitor that blocks TGFβ1‐induced Smad2/3 activation, 23 to the KG1a culture. In ESAM‐Neg KG1a, the addition of a small amount of SB525334 inhibited the upregulation of ESAM expression (Figure S6A). Surprisingly, when cultured with SB525334 for 3 days, the growth of KG1a cells was markedly inhibited (Figure 7A left); the variability of ESAM expression was also suppressed (Figure S6B). Moreover, Annexin V staining revealed that blocking TGFβ signaling by SB525334 induced cell death of KG1a (Figure 7A right). These results indicate that blocking the TGFβ signaling not only inhibited the phenotypic variability but also induced apoptosis in KG1a cells. While long‐term inhibition of TGFβ signaling induced significant cell death, the effect of short‐term SB525334, for 24 hours, was subtle (Figure 7B). However, together with antitumor drug daunorubicin, short‐term SB525334 treatment significantly enhanced the antitumor effect (Figure 7B), suggesting that inhibition of TGFβ signaling in combination with other drugs would have a stronger antitumor activity.

FIGURE 7.

Blocking TGFβ pathways induces cell death of leukemia cells. A, KG1a were cultured with or without SB525334 (5 μM). DMSO was used as a control. After 72 hours, cells were collected (n = 3). (Left) Ratio of cell number to day 0. (Middle) Representative flow cytometric data of Annexin V and 7‐AAD staining. (Right) Positive rate of Annexin V and 7‐AAD. B, KG1a were cultured with or without daunorubicin (50 nM) and SB525334 (5 μM). After 24 hours, cells were collected (n = 3). (Left) Ratio of cell number to day 0. (Middle) Representative flow cytometric data. (Right) Positive rate of Annexin V and 7‐AAD. C, The CD34+ fraction of AML case #4 cells was sorted and cultured with or without SB525334 (5 μM). After 96 hours, cells were collected (n = 3). (Left) Ratio of cell number to day 0. (Middle) Representative flow cytometric data. (Right) Positive rate of Annexin V and 7‐AAD. D, The CD34+ fraction of AML case #8 cells was sorted and cultured with or without daunorubicin (50 nM) and SB525334 (5 μM). After 24 hours, cells were collected (n = 3). (Left) Ratio of cell number to day 0. (Middle) Representative flow cytometric data. (Right) Positive rate of Annexin V and 7‐AAD. Percentages of cells in each gate are indicated in each panel. Data are shown as means ± SEMs. Statistically significant differences are represented by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001)

Finally, we analyzed the effects of TGFβ signaling blockade on primary leukemia cells obtained from patients with AML. In ESAM− fractions of primary CD34+ AML cells, TGFβ signaling blockade by SB525334 inhibited the upregulation of ESAM as observed in KG1a (Figure S6C‐D). In addition, SB525334 suppressed the proliferation of primary CD34+ AML cells (Figures 7C left and S6F) and induced apoptosis (Figures 7C right and S6F) in AML case #4 and #17. In AML case #8, SB525334 alone did not suppress cell proliferation or induce apoptosis (Figure S6E) but enhanced the antitumor effect of daunorubicin (Figure 7D). From these results, we conclude that interfering with autocrine/paracrine TGFβ signaling mechanisms might be a promising new strategy to treat unresponsive AML.

4. DISCUSSION

The principal aim of this study was to further investigate the features of LSCs in human AML. We hypothesized that ESAM expression could mark LSCs in human AML; hence, we examined its levels in various AML samples. Although our finding of AML LSCs with variable expression of ESAM did not agree with our hypothesis, our approach provided insight into their inherent features, namely heterogeneity and variability. By analyzing the molecular mechanisms involved in the heterogeneity and variability of LSCs, we identified autocrine TGFβ secretion in AML cells, which provides an important clue for developing new strategies to treat AML.

While treatment results for many blood cancers have greatly improved in the past decades, AML remains a poor‐prognosis disease due to its high recurrence rate after treatment. The high recurrence rate is considered at least partly due to residual chemoresistant LSCs. Therefore, developing novel treatments targeting LSCs is essential. Previous studies have searched for specific antigens that are expressed specifically on LSCs, but not on normal HSCs, as therapeutic targets. Several molecules have been reported as LSC‐related antigens in human AML, such as CD44, 24 CD47, 25 , 26 CD96, 27 CLL‐1/CD371, 28 and TIM‐3. 29 Although therapies targeting these antigens are promising, it is uncertain if they are constantly expressed on LSCs during the treatment course. Indeed, AML cells exhibit heterogeneity in gene as well as surface antigen expression, 30 and the phenotype of LSCs varies significantly among patients. 10 , 11 Moreover, even within the same patient, LSCs show plasticity. It is therefore possible that a small subset of LSC clones without LSC‐specific antigens may remain and expand during antigen‐specific treatments. Furthermore, non‐LSCs may acquire additional mutations and transition to new LSC clones. For example, melanoma CSCs heterogeneously express numerous antigens, and the heterogeneous CSCs are reconstituted over time even when specific antigen‐positive cells are removed. 15 Thus, understanding the mechanisms underlying LSC heterogeneity is indispensable to realize curative remedies for AML.

Herein, we found that human AML cells display phenotypic heterogeneity in terms of ESAM expression. We have previously shown that normal HSC activity correlates positively with ESAM expression levels in the CD34+CD38− fraction. 19 The CD34+CD38− phenotype, which reflects immaturity of hematopoietic cells in healthy human BM, is also known to enrich LSC activity in AML9. Hence, we expected that ESAM would be useful as one of the LSC‐related antigens in human AML. However, even in the same AML clones, ESAM expression level and pattern differed substantially. In addition, primary AML cells obtained from patients not only exhibited heterogeneous ESAM expression pattern but also phenotypic variability regarding ESAM levels. Although there appears to be a downward hierarchical relation from ESAM+ to ESAM− AML cells, we also observed mutual interconversion between ESAM− and ESAM+ cells in most AML cases. While the rate of recovery of ESAM expression varied from case to case, in some cases both ESAM+ and ESAM− populations gave rise to the other with a similar activity. These results support previous reports suggesting the inherent plasticity of AML LSCs, 14 , 31 , 32 and imply that we could resolve the fundamental mechanisms underlying LSC plasticity by analyzing the molecular pathways regulating ESAM expression.

A similar phenotypic fluctuation in EML cells, a murine HSC clone, has been previously studied. 33 , 34 EML cells are heterogeneous regarding Sca1 expression, a traditional mouse HSC‐related marker. When sorted according to Sca1 expression levels and cultured, both Sca1Hi and Sca1Lo EML cells reconstitute the original heterogeneous population, whereas the two fractions differ in their affiliation to the erythroid lineage. This functional difference results from their transcriptomes, which vary even at the single‐cell level. In this study, we observed a similar phenomenon with respect to ESAM expression on human AML cells. The fluctuation of ESAM expression levels was regulated by gene transcription in concert with other genes involved in HSC function and differentiation (Figures 5 and S3). RNA sequencing results revealed the substantial differences between ESAM+ and ESAM− KG1a cells, particularly in the expression levels of cytokine receptors and adhesion molecules such as integrins. These observations suggest that ESAM expression distinguishes functionally different LSCs in one AML clone, whose preferable locations to grow, the so‐called “LSC niche,” probably also differ in the BM. Furthermore, this notion again emphasizes the importance of determining the molecular mechanisms that modulate the functional as well as phenotypic versatility of AML LSCs in order to eradicate them from the BM.

ESAM mediates cell‐cell interactions through homophilic binding and plays physiological roles in the tight junction of endothelial cells. 35 , 36 , 37 We previously found that ESAM has functional significance in normal HSCs. ESAM deficiency disrupts erythropoietic potential in both fetal and adult HSCs. 38 , 39 Since the migration of neutrophils to inflammatory sites is inhibited in ESAM‐deficient mice, ESAM is also thought to play a role in the motility of hematopoietic cells. 37 Notably, crosslinking of ESAM on normal HSCs with an anti‐ESAM antibody activates Rho GTPase, 39 which is known to induce cancer cell motility by actin polymerization. 40 Although direct evidences are lacking at this stage, ESAM expression may also contribute to the motility of AML LSCs.

We identified TGFβ signaling as an upstream regulator of ESAM expression; the deprivation of natural TGFβ from culture medium reduced the variety of ESAM expression pattern in KG1a cells, leading to a homogeneous ESAM‐intermediate population (Figure 6). This phenomenon suggests that the sensitivity and/or response to TGFβ signaling differ between ESAM+ and ESAM− cells even in a clonal population. This differential sensitivity might, at least in part, reflect the reciprocal pattern of TGFBR2 expression (Figure 6D). ESAM− cells with high TGFBR2 expression may activate the TGFβ signaling pathway, even under conditions of very low TGFβ1 concentrations, resulting in the upregulation of ESAM expression. Thus, there may be a possible feedback loop between TGFβ1‐producing ESAM+ cells and TGFβR2‐expressing ESAM−populations, which might contribute to the reconstitution of heterogeneity in clonal AML cells. A similar observation was reported with discrete normal HSC subtypes. In fact, at low concentrations, TGFβ stimulates the growth of myeloid‐biased HSCs but inhibits lymphoid‐biased HSCs. 41 , 42 Notably, the ESAM‐Hi fraction highly expressed CD33, a myeloid‐related marker, whereas the ESAM‐Neg fraction presented a lymphoid‐related transcriptome signature (Figure S3). The action of TGFβ thus seems to be complex and context‐dependent, and this cytokine is likely to confer different phenotypes and functions on individual hematopoietic cells.

Accumulating evidence has shown that aberrant TGFβ signaling is involved in the pathogenesis of human leukemia. 43 , 44 However, the activity of TGFβ on AML cells remains controversial. For example, mutations and deletions in SMAD4 or TGFBR2, which permit AML‐initiating cells to evade inhibition by TGFβ signaling pathway, are involved in some AML cases, 45 , 46 suggesting that TGFβ has suppressive effects on AML LSCs. Meanwhile, TGFβ produced by activated BM microenvironment enhances the aggressiveness of human MLL‐AF9 oncogene‐induced AML in mouse transplantation models. 47 These contradictory results may be explained by the different sensitivity to TGFβ among AML LSCs or by the different magnitude of TGFβ induction in each experimental model. Alternatively, TGFβ may inhibit the emergence of AML LSCs at the initiation of disease, but support their proliferation afterwards in most cases.

Our findings demonstrate that AML cells produce TGFβ at low concentration, which in turn supports their diversity and variability. This is critical since TGFβ is normally secreted in a latent form and its activation requires multiple steps including the accumulation in the extracellular matrix and the interaction with cell surface integrins. 48 Our data postulate that the activation of TGFβ signaling in AML cells occurs in a cell‐autonomous manner. In addition, previous studies have primarily focused on TGFβ1 production from leukemia‐supporting microenvironment, the “LSC niche,” which formed a conceptual therapeutic target. As observed with CSCs in glioma, 49 , 50 it is likely that AML LSCs produce TGFβ1 by autocrine secretion and thus form a favorable environment by themselves. In this context, it is remarkable that inhibition of TGFβ signaling by SB525334, a TGFβRI‐selective inhibitor, exhibited growth inhibitory and cell death‐inducing effects in primary AML cells as well as KG1a.

Given the differences in susceptibility to SB525334 among primary AML cells, each AML case must have a genetic status which corresponds to different dependence on TGFβ signaling. Nevertheless, inhibition of TGFβ signaling significantly enhanced the effects of daunorubicin even in cases where single agents were ineffective. Notably, the 5 μM concentration of SB525334 used during in vitro experimentation would be feasible with 10 mg/50 kg body according to our provisional calculations. Inhibition of TGFβ signaling has also been reported to enhance the efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myelogenous leukemia 51 , 52 and of cytarabine in AML cells. 53 Our results support those findings, and further emphasize that small compounds inhibiting TGFβ signaling could be promising therapeutic strategy against human AML.

Although our data propose a promising new therapeutic strategy, this study has some limitations. First, the phenotypic variability in LSCs has only been demonstrated in vitro. We have shown that primary AML cells present phenotypic heterogeneity and variability in culture, but it remains uncertain whether they are variable in vivo. Second, although our results are in accordance with recent findings using large data sets of cancer genomics, 54 the expression levels of only a single marker is not sufficient to determine the features of LSCs or associate them with patient survival. Thus, studies on other multiple LSC‐associated markers in addition to ESAM are warranted. Finally, whether inhibition of TGFβ signaling would enhance the therapeutic effects of antitumor drugs for AML in humans should be carefully tested. In future, it is necessary to extend our research to in vivo models to apply our findings to the clinical field.

5. CONCLUSION

We demonstrated that human AML cells show heterogeneous ESAM expression, and that ESAM− and ESAM+ AML cells are mutually convertible. ESAM variability is regulated by TGFβ1, involving autocrine cytokine secretion. Blockade of TGFβ signaling not only inhibits ESAM variability, but also induces leukemic cell growth inhibition and apoptosis. Although efficacy and safety of TGFβ signaling inhibitors in vivo warrants confirmational studies, we believe that the molecular mechanisms underlaying the regulation of leukemic cells variability can potentially be therapeutic targets, and the combination of known drugs with new strategies may lead to complete eradication of AML LSCs.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.S.: conception and design, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing; T.Y.: conception and design, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript; D.O., N.H.: collection and assembly of data, manuscript writing; T.S., T.I., Y.D., T.U., T.O., R.N., A.T., M.I., H.S., Y.K.: collection and assembly of data.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Human AML cells are heterogeneous in terms of ESAM expression levels. A, ESAM positive rate in whole leukemia cells. ESAM‐positive samples were defined as ones with ESAM‐positive cells >5%. B, Expression data of ESAM and CD45 in all specimens of AML and ALL in CD34+CD38− fractions. M1, M2, …, indicate FAB classification of human AML. Percentages of cells in each gate are indicated in each panel. Data are shown as means ± SEMs. Statistically significant differences are represented by asterisks (***P < .001).

Figure S2 AML cell lines present phenotypical variability of ESAM expression. A, ESAM and CD45 expression of CMK. Percentages of cells in each gate are shown in each panel. B, CMK cells were sorted into four different groups according to ESAM expression levels. The sorted cells were cultured for 28 days. ESAM expression levels at the time of sorting, and on day 14, 21, and 28 are shown. C, ESAM‐Hi and ESAM‐Neg fractions were re‐sorted in KG1a cells in which ESAM expression was reconstituted from ESAM‐Neg fractions by continuous culture. The re‐sorted cells were cultured for 14 days. ESAM and CD45 expression at the time of sorting, and on day 14 are shown. Percentages of cells in each gate are indicated in each panel.

Figure S3 Clonal leukemia cells represent transcriptome heterogeneity. A, Top 16 genes that were upregulated by ESAM‐Hi or ESAM‐Neg. Fold changes were calculated as the ratio of ESAM‐Hi to ESAM‐Neg, or ESAM‐Neg to ESAM‐Hi. B, ITGA2B, ITGB7, SPP1, TIM3, BAALC, KLRC1, RGS1, and BCL6 mRNA levels in CD34+CD38−KG1a analyzed using real‐time RT‐PCR (n = 3). C, ITGB7 mRNA levels after single‐cell culture analyzed using real time RT‐PCR (n = 3). Single cell with ESAM‐Neg or ESAM‐Hi of CD34+CD38−fraction of KG1a was sorted and cultured for 28 days. ESAM‐Neg and ESAM‐Hi fraction cells were sorted again from the clones after culturing. D, ESAM, ITGA2B, ITGB7, SPP1, TIM‐3, BAALC, KLRC1, RGS1, and BCL6 mRNA levels in CMK analyzed using real‐time RT‐PCR (n = 3). Data are shown as means ± SEMs. Statistically significant differences are represented by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01, *** P < .001).

Figure S4 Detailed network analysis revealed cell maturation‐related genes to be mostly inhibited in the ESAM‐Hi fraction. Regulator network analysis of “maturation of blood cells” based on IPA database. Orange is the upregulated gene in ESAM‐Hi and green is the downregulated gene. Red is a factor predicted to upregulated and blue is a factor predicted to downregulated. The solid line shows a direct functional interaction of the products of the two genes, while the dotted lines indicate indirect interactions.

Figure S5 The phosphorylation level of Smad2/3 corresponds to TGFβ activation in ESAM‐Hi compared with ESAM‐Neg cells. Immunoblot analysis of Phospho‐Smad2/3 in ESAM‐Neg or ESAM‐Hi fraction of KG1a; β‐actin was used as the internal control. KG1a stimulated with TGFβ1 was used as positive control, while water was used as negative control.

Figure S6 Blocking TGFβ pathways induce cell death of leukemia cells. A, KG1a ESAM‐Neg cells were cultured in medium with or without SB525334 (3 μM). ESAM and CD45 expression at the time of sorting(left), on day7 without (middle), and with (right) SB525334 are shown. The percentage of cells in each gate is indicated in each panel. B, KG1a cells were cultured in medium with or without SB525334 (5 μM). ESAM and CD45 expression on day 0 (left) and on day 3 without (middle) or with (right) SB525334 is shown. The percentage of cells in each gate is indicated in each panel. C and D, The CD34+ESAM− fraction of AML case #4 cells was sorted and cultured with or without SB525334 (3 μM) for 7 days. ESAM and CD45 expression at the time of sorting (left), on day 7 without (middle) and with (right) SB525334 are shown. E and F, The CD34+ fraction of AML case #8 and #17 cells was sorted and cultured with or without SB525334 (5 μM). After 96 hours, cells were collected (n = 3). (Left) Ratio of cell number to day 0. (Right) Positive rate of Annexin V and 7‐AAD. Data are shown as means ± SEMs. Statistically significant differences are represented by asterisks (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001).

Table S1 Antibodies used in this study, related to Figures 1‐4, 6, 7, S1, S2, S5, and S6.

Table S2 Primers used in this study, related to Figures 5, 6, and S3.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Hasegawa, Ms. Habuchi, Ms. Shih and Mr. Takashima for technical support. We would like to thank Editage (http://www.editage.com) for editing and reviewing this manuscript for English language. This work was supported by grants from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (grant no. 20K16356).

Shingai Y, Yokota T, Okuzaki D, et al. Autonomous TGFβ signaling induces phenotypic variation in human acute myeloid leukemia. Stem Cells. 2021;39:723–736. 10.1002/stem.3348

Funding information Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI, Grant/Award Number: 20K16356

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Batlle E, Clevers H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat Med. 2017;23(10):1124‐1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dzobo K, Senthebane DA, Ganz C, et al. Advances in therapeutic targeting of cancer stem cells within the tumor microenvironment: an updated review. Cells. 2020;9(8):1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li L, Bhatia R. Stem cell quiescence. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(15):4936‐4941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Najafi M, Mortezaee K, Majidpoor J. Cancer stem cell (CSC) resistance drivers. Life Sci. 2019;234:116781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells: current status and evolving complexities. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(6):717‐728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dzobo K, Senthebane DA, Rowe A, et al. Cancer stem cell hypothesis for therapeutic innovation in clinical oncology? Taking the root out, not chopping the leaf. OMICS. 2016;20(12):681‐691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eun K, Ham SW, Kim H. Cancer stem cell heterogeneity: origin and new perspectives on CSC targeting. BMB Rep. 2017;50(3):117‐125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Najafi M, Mortezaee K, Ahadi R. Cancer stem cell (a)symmetry & plasticity: tumorigenesis and therapy relevance. Life Sci. 2019;231:116520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367(6464):645‐648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taussig DC, Vargaftig J, Miraki‐Moud F, et al. Leukemia‐initiating cells from some acute myeloid leukemia patients with mutated nucleophosmin reside in the CD34(−) fraction. Blood. 2010;115(10):1976‐1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eppert K, Takenaka K, Lechman ER, et al. Stem cell gene expression programs influence clinical outcome in human leukemia. Nat Med. 2011;17(9):1086‐1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goardon N, Marchi E, Atzberger A, et al. Coexistence of LMPP‐like and GMP‐like leukemia stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(1):138‐152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Majeti R, Weissman IL. Human acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells revisited: there's more than meets the eye. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(1):9‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sarry JE, Murphy K, Perry R, et al. Human acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells are rare and heterogeneous when assayed in NOD/SCID/IL2Rγc‐deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(1):384‐395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quintana E, Shackleton M, Foster HR, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity among tumorigenic melanoma cells from patients that is reversible and not hierarchically organized. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(5):510‐523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schober M, Fuchs E. Tumor‐initiating stem cells of squamous cell carcinomas and their control by TGF‐β and integrin/focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(26):10544‐10549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dosch JS, Ziemke EK, Shettigar A, Rehemtulla A, Sebolt‐Leopold JS. Cancer stem cell marker phenotypes are reversible and functionally homogeneous in a preclinical model of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75(21):4582‐4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yokota T, Oritani K, Butz S, et al. The endothelial antigen ESAM marks primitive hematopoietic progenitors throughout life in mice. Blood. 2009;113(13):2914‐2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ishibashi T, Yokota T, Tanaka H, et al. ESAM is a novel human hematopoietic stem cell marker associated with a subset of human leukemias. Exp Hematol. 2016;44(4):269‐281.e261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3(7):730‐737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ishikawa F, Yoshida S, Saito Y, et al. Chemotherapy‐resistant human AML stem cells home to and engraft within the bone‐marrow endosteal region. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(11):1315‐1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rojas A, Padidam M, Cress D, Grady WM. TGF‐beta receptor levels regulate the specificity of signaling pathway activation and biological effects of TGF‐beta. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793(7):1165‐1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grygielko ET, Martin WM, Tweed C, et al. Inhibition of gene markers of fibrosis with a novel inhibitor of transforming growth factor‐beta type I receptor kinase in puromycin‐induced nephritis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313(3):943‐951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jin L, Hope KJ, Zhai Q, Smadja‐Joffe F, Dick JE. Targeting of CD44 eradicates human acute myeloid leukemic stem cells. Nat Med. 2006;12(10):1167‐1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jaiswal S, Jamieson CH, Pang WW, et al. CD47 is upregulated on circulating hematopoietic stem cells and leukemia cells to avoid phagocytosis. Cell. 2009;138(2):271‐285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Majeti R, Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, et al. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell. 2009;138(2):286‐299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hosen N, Park CY, Tatsumi N, et al. CD96 is a leukemic stem cell‐specific marker in human acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(26):11008‐11013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Rhenen A, van Dongen GA, Kelder A, et al. The novel AML stem cell associated antigen CLL‐1 aids in discrimination between normal and leukemic stem cells. Blood. 2007;110(7):2659‐2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kikushige Y, Shima T, Takayanagi S, et al. TIM‐3 is a promising target to selectively kill acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(6):708‐717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Papaemmanuil E, Döhner H, Campbell PJ. Genomic classification in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):900‐901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kreitz J, Schönfeld C, Seibert M, et al. Metabolic plasticity of acute myeloid leukemia. Cells. 2019;8(8):805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang TY, Majeti R. Targeting LSCs: peeling back the curtain on the metabolic complexities of AML. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;27(5):693‐695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chang HH, Hemberg M, Barahona M, Ingber DE, Huang S. Transcriptome‐wide noise controls lineage choice in mammalian progenitor cells. Nature. 2008;453(7194):544‐547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pina C, Fugazza C, Tipping AJ, et al. Inferring rules of lineage commitment in haematopoiesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(3):287‐294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ki H, Ishida T, Penta K, et al. Cloning of an immunoglobulin family adhesion molecule selectively expressed by endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(19):16223‐16231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nasdala I, Wolburg‐Buchholz K, Wolburg H, et al. A transmembrane tight junction protein selectively expressed on endothelial cells and platelets. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(18):16294‐16303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wegmann F, Petri B, Khandoga AG, et al. ESAM supports neutrophil extravasation, activation of rho, and VEGF‐induced vascular permeability. J Exp Med. 2006;203(7):1671‐1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sudo T, Yokota T, Okuzaki D, et al. Endothelial cell‐selective adhesion molecule expression in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells is essential for erythropoiesis recovery after bone marrow injury. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0154189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ueda T, Yokota T, Okuzaki D, et al. Endothelial cell‐selective adhesion molecule contributes to the development of definitive hematopoiesis in the fetal liver. Stem Cell Rep. 2019;13(6):992‐1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hanna S, El‐Sibai M. Signaling networks of Rho GTPases in cell motility. Cell Signal. 2013;25(10):1955‐1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Challen GA, Boles NC, Chambers SM, Goodell MA. Distinct hematopoietic stem cell subtypes are differentially regulated by TGF‐beta1. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(3):265‐278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Blank U, Karlsson S. TGF‐β signaling in the control of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2015;125(23):3542‐3550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim SJ, Letterio J. Transforming growth factor‐beta signaling in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Leukemia. 2003;17(9):1731‐1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dong M, Blobe GC. Role of transforming growth factor‐beta in hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2006;107(12):4589‐4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Imai Y, Kurokawa M, Izutsu K, et al. Mutations of the Smad4 gene in acute myelogeneous leukemia and their functional implications in leukemogenesis. Oncogene. 2001;20(1):88‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Walter MJ, Payton JE, Ries RE, et al. Acquired copy number alterations in adult acute myeloid leukemia genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(31):12950‐12955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Krause DS, Fulzele K, Catic A, et al. Differential regulation of myeloid leukemias by the bone marrow microenvironment. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1513‐1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shi M, Zhu J, Wang R, et al. Latent TGF‐β structure and activation. Nature. 2011;474(7351):343‐349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ikushima H, Todo T, Ino Y, Takahashi M, Miyazawa K, Miyazono K. Autocrine TGF‐beta signaling maintains tumorigenicity of glioma‐initiating cells through Sry‐related HMG‐box factors. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5(5):504‐514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cao Z, Flanders KC, Bertolette D, et al. Levels of phospho‐Smad2/3 are sensors of the interplay between effects of TGF‐beta and retinoic acid on monocytic and granulocytic differentiation of HL‐60 cells. Blood. 2003;101(2):498‐507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Naka K, Hoshii T, Muraguchi T, et al. TGF‐beta‐FOXO signalling maintains leukaemia‐initiating cells in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2010;463(7281):676‐680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Naka K, Ishihara K, Jomen Y, et al. Novel oral transforming growth factor‐β signaling inhibitor EW‐7197 eradicates CML‐initiating cells. Cancer Sci. 2016;107(2):140‐148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tabe Y, Shi YX, Zeng Z, et al. TGF‐β‐neutralizing antibody 1D11 enhances cytarabine‐induced apoptosis in AML cells in the bone marrow microenvironment. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e62785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dzobo K, Ganz C, Thomford NE, Senthebane DA. Cancer stem cell markers in relation to patient survival outcomes: lessons for integrative diagnostics and next‐generation anticancer drug development. OMICS. 2020. Online ahead of print. 10.1089/omi.2020.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Human AML cells are heterogeneous in terms of ESAM expression levels. A, ESAM positive rate in whole leukemia cells. ESAM‐positive samples were defined as ones with ESAM‐positive cells >5%. B, Expression data of ESAM and CD45 in all specimens of AML and ALL in CD34+CD38− fractions. M1, M2, …, indicate FAB classification of human AML. Percentages of cells in each gate are indicated in each panel. Data are shown as means ± SEMs. Statistically significant differences are represented by asterisks (***P < .001).

Figure S2 AML cell lines present phenotypical variability of ESAM expression. A, ESAM and CD45 expression of CMK. Percentages of cells in each gate are shown in each panel. B, CMK cells were sorted into four different groups according to ESAM expression levels. The sorted cells were cultured for 28 days. ESAM expression levels at the time of sorting, and on day 14, 21, and 28 are shown. C, ESAM‐Hi and ESAM‐Neg fractions were re‐sorted in KG1a cells in which ESAM expression was reconstituted from ESAM‐Neg fractions by continuous culture. The re‐sorted cells were cultured for 14 days. ESAM and CD45 expression at the time of sorting, and on day 14 are shown. Percentages of cells in each gate are indicated in each panel.

Figure S3 Clonal leukemia cells represent transcriptome heterogeneity. A, Top 16 genes that were upregulated by ESAM‐Hi or ESAM‐Neg. Fold changes were calculated as the ratio of ESAM‐Hi to ESAM‐Neg, or ESAM‐Neg to ESAM‐Hi. B, ITGA2B, ITGB7, SPP1, TIM3, BAALC, KLRC1, RGS1, and BCL6 mRNA levels in CD34+CD38−KG1a analyzed using real‐time RT‐PCR (n = 3). C, ITGB7 mRNA levels after single‐cell culture analyzed using real time RT‐PCR (n = 3). Single cell with ESAM‐Neg or ESAM‐Hi of CD34+CD38−fraction of KG1a was sorted and cultured for 28 days. ESAM‐Neg and ESAM‐Hi fraction cells were sorted again from the clones after culturing. D, ESAM, ITGA2B, ITGB7, SPP1, TIM‐3, BAALC, KLRC1, RGS1, and BCL6 mRNA levels in CMK analyzed using real‐time RT‐PCR (n = 3). Data are shown as means ± SEMs. Statistically significant differences are represented by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01, *** P < .001).

Figure S4 Detailed network analysis revealed cell maturation‐related genes to be mostly inhibited in the ESAM‐Hi fraction. Regulator network analysis of “maturation of blood cells” based on IPA database. Orange is the upregulated gene in ESAM‐Hi and green is the downregulated gene. Red is a factor predicted to upregulated and blue is a factor predicted to downregulated. The solid line shows a direct functional interaction of the products of the two genes, while the dotted lines indicate indirect interactions.

Figure S5 The phosphorylation level of Smad2/3 corresponds to TGFβ activation in ESAM‐Hi compared with ESAM‐Neg cells. Immunoblot analysis of Phospho‐Smad2/3 in ESAM‐Neg or ESAM‐Hi fraction of KG1a; β‐actin was used as the internal control. KG1a stimulated with TGFβ1 was used as positive control, while water was used as negative control.

Figure S6 Blocking TGFβ pathways induce cell death of leukemia cells. A, KG1a ESAM‐Neg cells were cultured in medium with or without SB525334 (3 μM). ESAM and CD45 expression at the time of sorting(left), on day7 without (middle), and with (right) SB525334 are shown. The percentage of cells in each gate is indicated in each panel. B, KG1a cells were cultured in medium with or without SB525334 (5 μM). ESAM and CD45 expression on day 0 (left) and on day 3 without (middle) or with (right) SB525334 is shown. The percentage of cells in each gate is indicated in each panel. C and D, The CD34+ESAM− fraction of AML case #4 cells was sorted and cultured with or without SB525334 (3 μM) for 7 days. ESAM and CD45 expression at the time of sorting (left), on day 7 without (middle) and with (right) SB525334 are shown. E and F, The CD34+ fraction of AML case #8 and #17 cells was sorted and cultured with or without SB525334 (5 μM). After 96 hours, cells were collected (n = 3). (Left) Ratio of cell number to day 0. (Right) Positive rate of Annexin V and 7‐AAD. Data are shown as means ± SEMs. Statistically significant differences are represented by asterisks (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001).

Table S1 Antibodies used in this study, related to Figures 1‐4, 6, 7, S1, S2, S5, and S6.

Table S2 Primers used in this study, related to Figures 5, 6, and S3.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.