Abstract

Purpose:

Childhood maltreatment is associated with increased suicide risk. However, not all maltreated children report self-injurious thoughts and behaviors, highlighting the presence of other risk factors. Notably, adolescent dating violence (ADV) and child maltreatment are highly comorbid, with ADV also linked to suicide risk among adolescents. Current research further suggests that distinct patterns of ADV involvement are differentially related to adolescent mental health. To date, it is unknown whether differences in ADV patterns moderate changes in suicide risk for adolescents with and without a maltreatment history. This study aims to advance the literature by identifying patterns of ADV in a unique sample of adolescents and by determining the differential association between maltreatment and suicidal ideation and non-suicidal self-harming behaviors based on ADV profiles.

Methods:

Participants were racially and ethnically diverse low-income non-treatment-seeking adolescent females with elevated depressive symptoms, ages 13–16 (N=198).

Results:

Using latent class analysis, we found support for a 3-class model of dating violence: adolescent females without ADV involvement, those in relationships with mutual verbal abuse, and those in romantic relationships with multiple and more severe forms of ADV, such as verbal abuse and physical violence. A series of latent class moderation models indicated that the effect of child maltreatment on suicidal ideation significantly differed based on ADV class membership.

Conclusion:

Results highlight the importance of considering different ADV patterns and maltreatment as interactive risk factors for increased self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Intervention and prevention approaches relevant to maltreated youths are discussed for families and practitioners.

Keywords: maltreatment, dating violence, adolescent, suicide, depression

Child maltreatment represents an extreme form of maladaptive parenting characterized by the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse and/or the physical and emotional neglect of a child (Cicchetti & Toth, 2016; Sedlak et al., 2010). Within the United States, child abuse and neglect are ubiquitous, with approximately 670,000 children found to be victims of child maltreatment in 2017 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017). Child maltreatment is associated with a myriad of adverse psychological sequelae such as non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), suicidal thoughts and suicidal behaviors among maltreated youths (Glassman, Weierich, Hooley, Deliberto, & Nock, 2007; Handley, Adams, Manly, Cicchetti, & Toth, 2018; Miller, Esposito-Smythers, Weismoore, & Renshaw, 2013). Moreover, self-reported child maltreatment is associated with an almost two-fold increase in suicide attempts in adulthood, even after controlling for other financial and psychological factors (Martin, Dykxhoorn, Afifi, & Colman, 2016). Although much work has been done investigating the consequences of child maltreatment, it is noteworthy that not all individuals with histories of maltreatment develop psychopathology (Cicchetti, 2013), underscoring the crucial role of risk and protective factors.

Current evidence highlights interpersonally-salient factors as related to increased psychopathology risk in maltreated youth. For instance, maltreated youth who are at increased risk for suicidal ideation and attempts are those with less perceived social support (Esposito & Clum, 2002; Miller et al., 2013). Impaired relationship quality and conflictual relationships with caregivers also mediate the link between a childhood history of maltreatment and adolescent suicidal ideation (Handley et al., 2018). However, much less is known about how conflicts in other salient interpersonal domains, such as the presence of violence in early romantic relationships, contribute to increased self-injurious thoughts and behaviors among maltreated adolescents. To date, no study has examined whether involvement in unhealthy or violent romantic relationships moderates the association between child maltreatment and adolescent suicide risk. Thus, the purpose of this study is to investigate whether the association between maltreatment and adolescent suicidal ideation and self-injurious behaviors varies based on their involvement in different dating violence patterns.

Adolescent Dating Violence and Child Maltreatment.

Adolescent dating violence (ADV) involves the engagement or the threat of engagement in physically, sexually, or psychologically/emotionally abusive behavior by or towards a romantic partner (Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012). Dating violence is alarmingly prevalent for adolescents; conservative estimates indicate that approximately 31% of youth have experienced some form of violence within a romantic relationship in the past 12 months, with high frequencies of different types of abuse also apparent in their romantic relationships (Vagi, Olsen, Basile, & Vivolo-Kantor, 2015; Ybarra, Espelage, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Korchmaros, & Boyd, 2016). Violence in adolescent romantic relationships is also often mutual (Capaldi et al., 2007; Goncy et al., 2018). In addition to other adverse health behaviors, substantially higher rates of suicidal behaviors have been found for adolescents in violent romantic relationships (Silverman, Raj, Mucci, & Hathaway, 2001; Vagi et al., 2015).

Investigating ADV’s link with self-injurious thoughts and behaviors among maltreated youth is especially important since current evidence consistently demonstrates that maltreatment exposure and adolescent dating violence involvement are highly comorbid (Capaldi et al., 2012; Laporte, Jiang, Pepler, & Chamberland, 2011; Wolfe, Scott, Wekerle, & Pittman, 2001). In fact, a nationally representative survey found that adolescents who are victims of child maltreatment are almost twice as likely to also report physical dating violence victimization, compared to teens without a maltreatment history (Hamby, Finkelhor, & Turner, 2012). Thus, for maltreated children, exposure to subsequent conflict and violence in their romantic relationship may increase their risk for psychological problems, like suicidal ideation and non-suicidal self-injury.

Adolescent Dating Violence Patterns.

Beyond examining the direct link from adolescent dating violence to adolescent mental health, substantially more work is needed to understand whether differences in dating violence patterns (e.g., types of aggressive behavior, victim versus perpetrator or bidirectional) change the relationship between maltreatment history and suicide risk for adolescents. Accordingly, the ADV literature has begun to investigate whether unique patterns exist across dating violence behaviors using person-centered analytical approaches (e.g., Latent Class Analysis). A major benefit of a person-centered approach is the ability to identify distinct and homogeneous subgroups of individuals based on similar experiences of dating violence behaviors (Collins & Lanza, 2010). An additional advantage is that identification of distinct classes can be informative for investigating whether differences in psychopathology risk exist for these unique classes, all of which has important implications for tailored prevention and intervention efforts (Choi, Weston, & Temple, 2017; Reyes, Foshee, Chen, & Ennett, 2017).

Current findings are mixed on the exact number and configuration of dating violence patterns that typify adolescent romantic relationships. Of the five studies that have investigated adolescent dating violence patterns, all found support for a group of adolescents involved in no dating violence and for two other classes characterized by a combination of perpetration and victimization across different types of aggressive behavior. However, whereas two of these studies exclusively found these three patterns (Haynie et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2017), three other studies identified two additional classes comprised of teens who were typically only victims or only perpetrators of dating violence (Choi et al., 2017; Goncy, Sullivan, Farrell, Mehari, & Garthe, 2017; Sullivan et al., 2019).

Recent research on ADV typologies also demonstrates differential associations between ADV profiles and important adolescent mental health and behavioral concerns, including anxiety, depression, substance use and delinquent behaviors (Choi et al., 2017; Goncy et al., 2017; Haynie et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2017). However, the extant literature is limited. Notably, among the few studies done on ADV classes, these patterns have been predominantly investigated as correlates of psychopathology, without consideration of how ADV patterns exacerbate other vulnerability factors for psychopathology. To our knowledge, only one study has investigated the moderating role of dating violence patterns. Choi and colleagues (2017) found that adolescent dating violence class membership moderated the links between gender, race/ethnicity, parental education as well as beliefs about the acceptability of violence and adolescent mental health. Given the negative role of relational conflict with suicide risk, including the higher rates of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors among adolescents with maltreatment histories and adolescents involved in dating violence, it is expected that the interactive effects of exposure to different types of relational violence will increase risk for suicidal ideation and non-suicidal self-harming among dually affected youth. Moreover, no study has yet examined whether and how dating violence patterns differentially effects maltreatment’s association with suicide risk factors.

Present Study

The present study adds to the literature by both (1) identifying patterns of adolescent dating violence within a unique sample of racially and ethnically diverse, low-income, non-treatment-seeking adolescent females with and without maltreatment histories and with elevated depressive symptoms and (2) by investigating whether identified ADV patterns moderate the association between maltreatment and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors for these adolescents. The current study’s use of a high-risk (e.g., maltreated, depressed, low-income, predominantly racial minority) adolescent sample is warranted to understand the mental health risk and needs of this understudied population based on their exposure to different types of relational violence. For instance, disproportionately high rates of maltreatment, dating violence victimization and perpetration, and polyvictimization has been reported for non-White youth (Ford et al., 2010; Haynie et al., 2013; Malik et al., 1997; Reyes et al., 2017; Vagi et al., 2015). Furthermore, mid-adolescence (i.e., around age 15) represents a period in which youth are at increased risk for the onset of polyvictimization (Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, & Holt, 2009). The emergence of adolescence also coincides with increased onset of depression (Kessler, 2003), suicidal ideation (Nock et al., 2008), and non-suicidal self-injury (Cipriano, Cella, & Cotrufo, 2017). Moreover, because deficits in interpersonal connections are also thought to promote depression and suicide risk (Hammen, 2003; Joiner, 2007; Van Orden et al., 2010) adolescent females with depressive symptoms may be particularly susceptible to self-harming thoughts and behaviors in the presence of negative relational experiences, such as maltreatment and dating violence. Thus, the inclusion of maltreated and non-maltreated adolescent females with depressive symptoms provides a unique opportunity to contextualize changes in suicide risk during a developmental period in which these youths are especially vulnerable to different types of relational violence and psychological harm. In addition to the at-risk sample, the current study also utilizes both parent and adolescent report of NSSI behaviors and includes both adolescent dating violence victimization and perpetration across multiple types of dating violence behaviors.

Based on the 3–5 classes of adolescent dating violence found in previous research, it is expected that at least three distinct classes of dating violence will emerge. Additionally, we hypothesize that patterns of dating violence will similarly reflect those identified in previous studies, with these patterns characterized by: (1) adolescents who are uninvolved in violence, (2) those who engage in mutual psychological/verbal dating aggression, (3) those who are involved in a combination of different types of violent behaviors as perpetrator and victim, and/or (4) those that are either only victims of dating violence or (5) perpetrators of dating violence. We further hypothesized that a history of child maltreatment would be associated with increased suicidal ideation and non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors, and that these relations would be moderated by ADV patterns. No specific a priori hypothesis was made about which dating violence pattern would more strongly moderate maltreatment’s association with self-harming thoughts and behaviors.

Method

Participants

Participants for the current investigation included adolescent females (N=198) aged 13–16 and their mothers1 from an urban setting in upstate New York. Data for the present study were drawn from the baseline assessment of a larger randomized controlled trial. Adolescent females were on average 14 years old (SD=.85) and mothers were on average 39.03 years old (SD=6.46). The majority of adolescents (64.8%) and mothers (64.6%) were African-American, 22.6% of adolescents and 24% of mothers were white, and 12.5% of adolescents and 11.5% of mothers identified as multiple or other races. 14.1% of adolescents and 9.4% of mothers were Latinx. The majority of mothers were not married (78%), and the average total family income was $28,040.

Procedures

Informed consent was obtained from parents for participation in the research. Assent was obtained from adolescents. To be eligible for the study, all families had to be eligible for Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF). Multiple methods were utilized to recruit children in the maltreated group, including collaborating with the University of Rochester Medical Center’s pediatric social workers, contacting schools and organizations that served adolescents, recruitment in Department of Human Services (DHS) waiting rooms, and through a DHS liaison who examined Child Protective Services (CPS) reports to identify children who had been maltreated and/or were part of a family with a history of maltreatment. Children living in foster care often experience early and extreme maltreatment. They were not recruited for the current investigation to reduce heterogeneity among the maltreated sample. The collaborating recruitment partners contacted eligible families and described the study. Parents who were interested in having their child participate provided signed permission for their contact information to be shared with project staff.

Because maltreating families primarily are of low socioeconomic status (National Incidence Study – NIS-4; Sedlak et al., 2010), nonmaltreating families were recruited from those receiving TANF in order to ensure socioeconomic comparability. A DHS liaison contacted eligible nonmaltreating families and described the project. Parents who were interested in participating signed a release allowing their contact information to be given to project staff for enrollment.

All assessments were conducted between 2011 and 2016 by trained interviewers who were unaware of the maltreatment status of the adolescents or the study hypotheses. Because of possible variations in reading ability and literacy, all self-report measures were read to participants while they followed along and indicated their responses. Mothers and adolescents were interviewed simultaneously in separate rooms. All study procedures met approval by the University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Adolescent maltreatment.

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein et al., 2003) is a 25-item retrospective self-report measure of child maltreatment. Adolescents rated their lifetime experiences of maltreatment with response options ranging from 0=Never True to 5=Very True. Examples include “I got hit so hard by someone in my family that I had to see a doctor or go to the hospital,” and “When I was growing up, I didn’t have enough to eat.” Maltreatment subtypes include emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. Based on established cutoffs, the presence or absence of each subtype of maltreatment was determined (Walker et al., 1999). A summary of the number of maltreatment subtypes experienced by the adolescent was calculated (0–5) and used in subsequent analyses. The CTQ has evidenced good internal consistency (α = 0.66 – 0.92; Bernstein & Fink, 1998) and convergent validity with other self-report and interview measures of child maltreatment (Hyman, Garcia, Kemp, Mazure, & Sinha, 2005). In the current sample, 53.5% (n=106) of adolescent females indicated a history of some form of maltreatment. Of those adolescents with maltreatment histories, 44.9% met criteria for one subtype, 25.2% met criteria for two subtypes, 16.8% met criteria for three subtypes, 8.4% met criteria for four subtypes, and 4.7% met criteria for five subtypes. The mean number of subtypes experienced among adolescents with a maltreatment history was 2.03 (SD=1.18).

Maltreated (n=106) and non-maltreated (n=92) depressed females were equivalent on age, race, ethnicity, and mother’s race and ethnicity. Groups did not differ on the family’s total income, receipt of public assistance, or maternal marital status.

Adolescent dating violence.

Adolescents reported on dating violence in their current or most recent (past year) romantic relationship using the 7-item Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory derived from the larger measure (CADRI; Wolfe, Scott, Reitzel-Jaffe, Wekerle, Grasley, & Straatman, 2001). Although less items were included on the 7-item CADRI than compared to the original, items on the current version are the same or similar to items on the 10-item (short form) CADRI (Fernandez-Gonzalez, Wekerle, & Goldstein, 2012) and include items with strong factor loadings (.62-.84) on their respective first-order factors, based on the original CADRI validation study (Wolfe et al., 2001). Sample items include “My partner slapped me or pulled my hair,” and “I threatened to hit or throw something at my partner.” Seven items assessed for dating violence victimization and 7 for perpetration (3 items for physical violence, 2 for threatening behaviors and 1 each for sexual and verbal violence). Response options ranged from 0=Never to 4=Often. The following subtypes were included as latent class indicators: physical violence-victim, threatening behaviors-victim, verbal violence-victim, physical violence-perpetrator, threatening behaviors-perpetrator, and verbal violence-perpetrator. Sexual violence perpetration and victimization was not included in the analyses due to the low level of endorsement of these items (0% and 3%, respectively) and poor class distinction. Dating violence subtype summary scores were dichotomized such that experience with that subtype in the past year was coded “1” and no experience was coded “0”. Consistent with previous ADV latent class research (Reyes et al., 2017), adolescents involved in a romantic relationship without dating violence and those not yet dating were coded “0” for each dating violence subtype. Given the prevalence of dating violence and the presence of multiple risk factors for dating violence involvement among our sample, we conceptualized a lack of romantic dating initiation as potentially protective for maltreated and non-maltreated females with depressive symptoms, who may choose not to date, thereby reducing their risk for exposure to romantic conflict or violence. Inclusion of these teens also improves the generalizability of our findings to adolescent females of this age not in romantic relationships. Strong psychometric properties have been documented for the CADRI (Wolfe et al., 2001). In the current study, the internal consistency of the 7-item CADRI was α=.82.

In the current sample, 68.3% of adolescent females (n=136) reported having a romantic partner currently or in the past year. Among these females, the average age to start dating was 12.41 (SD=1.44) and they reported having had approximately 4 (SD=3.0) romantic partners in their lifetime (excluding childhood crushes). Prevalence rates for dating violence perpetration subtypes ranged from 17.6–45.2% and 7–45.7% for victimization, excluding sexual violence. Table 1 provides the percent of adolescent females who endorsed any type of exposure for the different types of dating violence.

Table 1.

Prevalence of subtypes of adolescent dating violence based on binary (0/1) indicators

| Adolescent Dating Violence subtype | % endorsement | n |

|---|---|---|

| Verbal abuse perpetration | 45.2 | 90 |

| Verbal abuse victimization | 45.7 | 91 |

| Threatening behavior perpetration | 18.1 | 36 |

| Threatening behavior victimization | 7.0 | 14 |

| Physical violence perpetration | 17.6 | 35 |

| Physical violence victimization | 8.0 | 16 |

Suicidal ideation.

Adolescents reported on their past two week suicidal ideation using two items the Beck Depression Inventory for Youth (BDI-Y; Beck et al., 2005). Item #4 (“I wish I was dead”) was initially scored on a 0–3 scale (0=“Never,” to 3=“Always”). Item #21 was initially coded on a 0–2 scale (0=“I do not think about killing myself”, 1=“I think about killing myself but I would not do it”, and 2=“I want to kill myself”). Both items were first recoded separately as a binary variable (i.e., each coded as 1 if the adolescent endorsed the item at any level greater than 0). The recoded items were then summed and treated as a continuous variable (0–2) with higher scores indicating the presence of increased suicidal ideation. Approximately 29% of the adolescents reported suicidal thoughts in the past 2-weeks.

Non-suicidal self-injury.

Non-suicidal self-injurious (NSSI) behaviors over the past 2 months were measured using both adolescent and parent-report from the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 1997), a psychometrically-sound parent-child diagnostic interview for developmentally relevant psychiatric disorders consistent with DSM-IV criteria. Example of NSSI behaviors included “cutting, burning, scratching, and erasing.” Scores for NSSI was based on a synthesize of both parent- and adolescent-report of the adolescent’s self-harming behaviors and rated on a 0–2 scale, with higher scores indicating greater frequency and/or severity of self-harming behaviors (0=not present, 1=subthreshold; “engaged in the behavior on 1 occasion with no serious injury to self” and 2=threshold; “engaged in the behavior more than once and/or has engaged in the behavior with significant injury to self.”). Approximately 16% of adolescents engaged in self-harming behavior in the past 2-months.

Depressive symptoms.

Adolescents self-reported on their past two-week depressive symptoms using the Beck Depression Inventory for Youth (BDI-Y; Beck et al., 2005). Consistent with prior literature, suicidal ideation items (items #4 and #21) were omitted from the BDI-Y total depressive score (i.e., Handley et al., 2018). This was done to avoid item overlap with the outcome variables and avoid an artificial inflation of the association between depressive symptoms and suicide-related outcomes. Summary score was calculated for the remaining 19 items (range=0–53; M=13.02, SD=9.81). Internal consistency for these 19 items was high (α = .92). Maltreated females reported significantly more depressive symptoms (M=15.63) than non-maltreated females (M=10.03) (p<.001).

Data Analytic Plan

Descriptive data analyses were conducted using SPSS 23. A series of latent class analyses were estimated in Mplus Version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017) to identify patterns of adolescent dating violence and to determine the appropriate number of subgroups based on responses to the CADRI items. Viability of each class solution was determined by the replication of the best loglikehood values and model convergence in each successively estimated class solution. Following recommendations by Collins and Lanza (2010), final model selection was based on comparison between class solutions on a number of statistical parameters, including the Akaike information criteria (AIC) and the Bayesian information criteria (BIC), the latter of which represents a more conservative estimation of model fit. Lower AIC and BIC values indicate a better fitting class solution. A significant p-value on the Lo-Mendell Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (aLRT) and/or the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) indicate a significant improvement in model fit between two comparative class-solutions. Additionally, interpretability, parsimony and conceptual support of the class solutions was considered in selecting the final LCA model. Within the selected model, the quality of the class distinctions was determined by the entropy value (≥.80) and the average latent class probabilities, which indicates the probability that individuals are likely to be in their assigned class compared to another class (≥.80 for own class).

After identifying the best fitting class solution, we conducted latent class moderation using the Bolck, Croon, & Hagenaars (BCH, 2004) approach (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014). This method is optimal for ensuring that the selected ADV classes are not substantially altered by the presence of other variables in subsequent analyses and that results can reliably be interpreted based on the final latent class solution. The BCH method creates weighted groups that correspond to each class, with auxiliary models then estimated based on these weights (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014). Using the BCH approach, we first saved the BCH weights from our final class solution, then estimated 2 separate regression auxiliary models (i.e., a suicidal ideation model and a NSSI model) regressed on maltreatment and conditional on the weights from our final class solution. Due to missing data on the outcome measures, the sample size varied between models (n=197 for suicidal ideation; n=190 for NSSI). Depressive symptoms (exclusive of symptoms related to suicidal ideation) was included as a covariate in the latent class moderation analyses to control for the higher rates of depressive symptoms among the maltreated adolescents. Maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) was used as the estimator as it results in better standard errors (Bakk & Vermunt, 2016). Figure 1 illustrates the proposed latent class moderation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of latent class moderation by ADV class membership

Determining significant moderation by class membership on the two regression auxiliary models were conducted using the Wald chi-square test, which is used to examine whether regression coefficients significantly differ across classes (Asparouhouv & Muthén, 2007). The Wald test is suitable for continuous and binary variables. We thus evaluated the equivalence of the regression coefficient by class membership for each of the models. Following a significant omnibus Wald test, pairwise comparisons were then conducted for maltreatment’s association with suicidal ideation and NSSI across the different ADV classes.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

As expected, a greater number of maltreatment subtypes was associated with more suicidal ideation (r=.34, p<.001) and NSSI behaviors (r=.35, p<.001). Additionally, a greater number of maltreatment subtypes was linked with an increase in the number of lifetime romantic partners (r=.24, p<.01), having a current partner that was older in age (r=.27, p<.01) and with a higher amount of dating violence exposure (i.e., combined total of dating violence victimization and perpetration; r=.14, p=.05). Dating violence perpetration and victimization across all subtypes was significantly and positively correlated with each other (rs=.30-.81, ps<.001).

Table 2 details the model fit indices for each latent class solution. Following a series of 5 sequentially estimated latent class models (4 of which successively converged and were identifiable), the 3-class solution was determined to be the best-fitting model based on the more conservative BIC index, the parsimoniousness and interpretability of the class solution, and the study’s small sample size. The model also evidenced good homogeneity within class and distinction between classes (entropy = .94, average latent class probabilities =.95–1.00). The 4-class solution was not selected for several reasons. First, the decrease in the AIC between the 3 and 4-class solution was small (less than 1), and the smallest class in the 4-class model was approximately 8% of the sample (n=16), which, given the sample size, is suggestive of low generalizability to the general population and low replicability of this class in subsequent studies. Substantive interpretability of the different classes is also an important consideration when selecting the most suitable class solution (Collins & Lanza, 2010). The additional group that emerged in the 4-class solution was statistically distinguished by high endorsement of one item that was conceptually related to and co-occurred with items endorsed in another ADV group found previously in the 3-class solution. Given the relatedness of the items, the additional class did not appear to be a meaningfully distinct group.

Table 2.

Latent Class Analysis Fit Statistics

| Free parameters | Loglikelihood | AIC | BIC | bLRTa | Smallest class % | Entropy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Class | 6 | −567.195 | 1146.389 | 1166.149 | --- | --- | --- |

| 2 Class | 13 | −402.844 | 831.687 | 874.500 | p<0.001 | 35% | .93 |

| 3 Class | 20 | −367.953 | 775.905 | 841.771 | p<0.001 | 15% | .94 |

| 4 Class | 27 | −360.620 | 775.240 | 864.159 | p<0.001 | 8% | .99 |

| 5 Class | 34 | −359.562 | 787.125 | 899.097 | p=.33 | 2% | .97 |

Represents p-values for the bootstrap likelihood ratio test.

Note: Bolded values indicate the lowest values found for each model fit statistics as well as the statistically significant improvement in fit between two comparative class solutions.

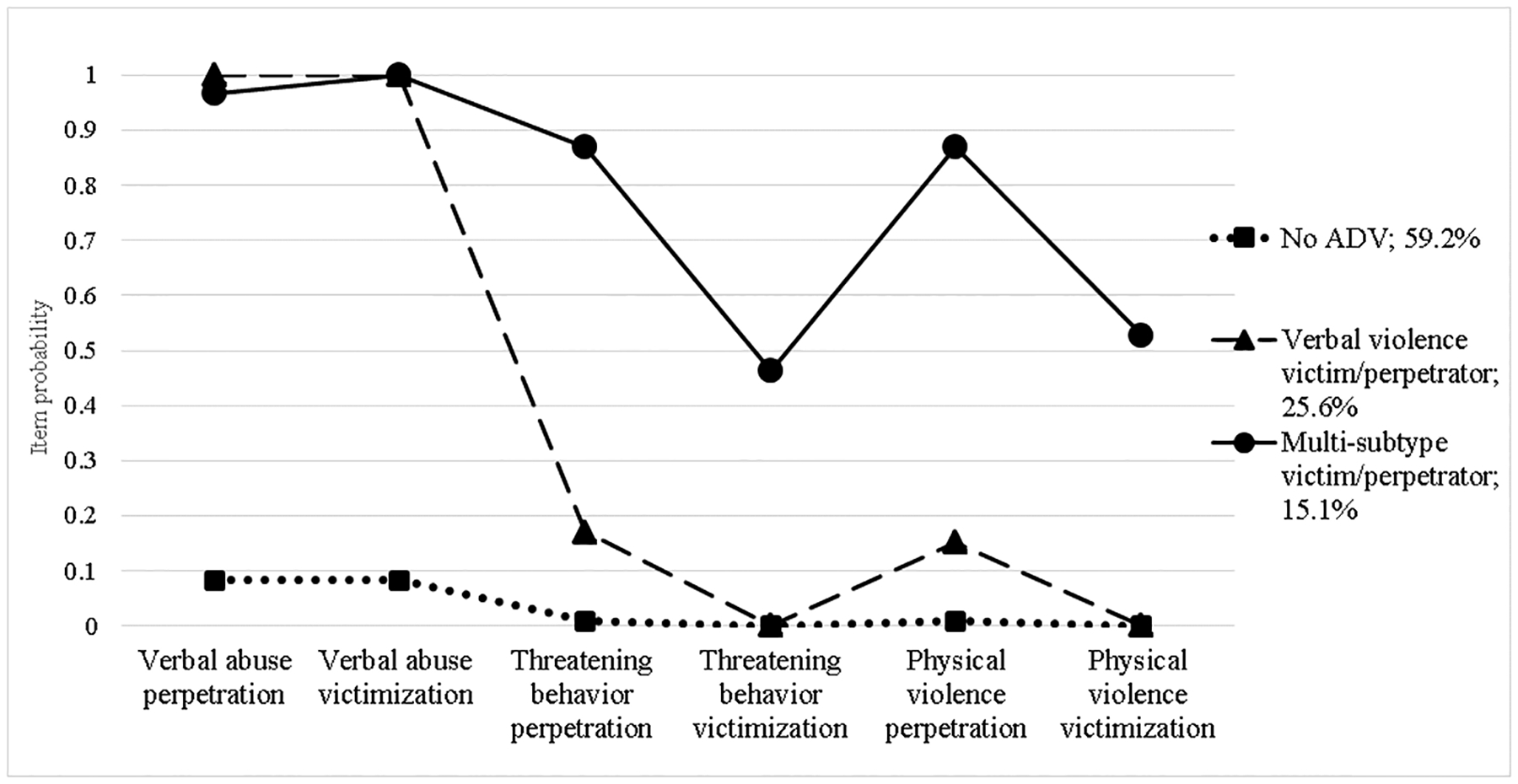

Figure 2 provides plots of the estimated probability of endorsing each ADV item by class for the retained 3-class model. Class 1 (no-ADV; n=118, 59.2%) represents adolescents with no dating violence as indicated by the low probability of endorsement across all perpetration and victimization items. Class 2 (verbal violence victim/perpetrator; n=51, 25.6%) consists of adolescents who reported mutual verbal violence in their intimate relationships, as indicated by the high probability of endorsement of verbal abuse perpetration and victimization items and the low probability of endorsement for threatening and physical violence perpetration and victimization items. Finally, Class 3 (multi-subtype victim/perpetrator; n=30, 15.1%) contains adolescent females who engaged in not only mutual verbal violence but also threatening behavior and physical violence perpetration in their intimate relationships.

Figure 2.

ADV item probability profile for 3-class solution

Note: Class 1 (dotted line; 59.2%): uninvolved in ADV; Class 2 (dashed line; 25.6%): verbal violence victims/perpetrator; Class 3 (solid line; 15.2%): multiple-subtype victim/perpetrator group.

Finally, we examined whether patterns of adolescent dating violence moderated the effect of the number of maltreatment subtypes on the two suicide risk factors: suicidal ideation and NSSI, with depressive symptoms as a covariate. Based on the Wald chi-square test, we found that the effects of a history of multiple maltreatment subtypes on past 2-week suicidal ideation significantly differed based on ADV class membership (χ2(2)=14.53, p=.001). Examination of pairwise comparisons between classes indicated significant differences between the no ADV class and the verbal violence victim/perpetrator group (b=−.16, p=.009) and the no ADV class and the multi-subtype victim/perpetrator group (b=−.29, p=.001). Compared to adolescents not involved in dating violence (b=−.04, p=.29), the effects of maltreatment on suicidal ideation was stronger for females in the verbal violence victim/perpetrator group (b=.12, p=.02) and the multi-subtype victim/perpetrator group (b=.25, p=.004). Similarly, the effects of a history of maltreatment on past 2-months non-suicidal self-injury was marginally significantly different based on ADV class membership (χ2(2)=5.57, p=.06). Examination of the pairwise comparisons indicated a significant difference between the no ADV class and the multi-subtype victim/perpetrator group (b=−.25, p=.02), such that compared to adolescents not involved in dating violence (b=.08, p=.27) the effects of maltreatment on self-harming behaviors was stronger for females in the multi-subtype victim/perpetrator group (b=.32, p<.001).

Additionally, sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine whether the latent class enumeration and moderation models changed if adolescent females not yet dating were removed from the analyses. Analyses with only dating adolescent females (n=136) indicates that the class enumeration models are the same and results of the latent class moderation model for suicidal ideation are the same. However, the moderating effect of ADV patterns on maltreatment’s association with NSSI went from marginally significant in the full (n=199) sample to non-significant in the n=136 sample. As mentioned previously, removing these non-dating girls limits the generalizability of our findings, particularly as these girls have a number of risk factors (e.g., maltreatment, depression, etc.) that are related to dating violence, but are instead opting not to date. The largely consistent latent class enumeration and moderation models support the inclusion of these adolescents in the analyses.

Discussion

The current study aimed to advance the literature on typologies of dating violence in adolescents by investigating whether the association between maltreatment and adolescent suicide risk factors varies depending on the pattern of adolescent dating violence. To date, this study is the first to examine ADV patterns in a sample of maltreated females with elevated depressive symptoms and is the first to investigate how maltreatment’s link to self-harming thoughts and behaviors changes as a function of dating violence patterns. Results of latent class analysis identified three distinct patterns of romantic relationships among adolescents: 1) no dating violence, 2) verbal violence victimization and perpetration, and 3) mutual verbal violence, physical violence and threatening behavior perpetration. The 3-class solution and the specific configuration of classes found were also consistent with two of the five studies on ADV subtypes (Haynie et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2017). However, unlike other studies (Choi et al., 2017; Goncy et al., 2017; Sullivan et al., 2019), we did not find support for a victim-only or perpetrator-only class. The small sample size of the current study may have prevented us from having the power necessary to identify unidirectional dating violence classes, which are typically a smaller subset of adolescents, relative to those not involved in any dating violence or those involved in mutual dating violence (Ybarra et al., 2016). Additionally, several characteristics of the current sample are associated with higher rates of dating violence mutuality or perpetration, including their gender, race, and maltreatment history, which may also have contributed to not identifying a victim-only class. In particular, mutual violence may be a more prominent pattern of dating violence among maltreated females with elevated depressive symptoms than among samples with less vulnerability factors. This is noteworthy because dating violence mutuality is also associated with more adverse outcomes. For instance, both adolescent and young adult intimate relationships characterized by mutual physical aggression are more likely to result in frequent or more severe injury to either or both partners (Capaldi et al., 2007; Gray & Foshee, 1997).

Our hypothesis that mutual ADV typologies would exacerbate the risk conferred by maltreatment for suicide ideation and NSSI among depressed adolescent females was also partially supported. Higher levels of maltreatment subtypes were related to suicidal ideation more strongly for adolescent females involved in bi-directional violent romantic relationships, regardless of whether these relationships were typified by verbal violence only or also included physical violence/threatening behaviors. The association of maltreatment and suicidal ideation was maintained even after accounting for other concurrent mental health concerns, such as depressive symptoms, which is consistent with previous work highlighting the unique link between maltreatment and suicide risk (for a review of the literature, see Miller et al., 2013). Furthermore, the importance of dating violence as a relational risk factor for suicidal ideation, above and beyond depressive symptoms, is also supported by prior literature examining conflictual parent-child relationship as a pathway between child maltreatment and adolescent suicidal ideation (Handley et al., 2018). The moderating effect of ADV patterns on maltreatment’s link to self-harming behaviors was marginally significant, with higher levels of maltreatment subtypes increasing NSSI more strongly for females in romantic relationships characterized by multiple types of violence, relative to females who reported no dating violence. This is consistent with previous research demonstrating greater psychological distress among teens in relationships typified by victimization and perpetration across multiples types of violent and unhealthy behaviors (Choi et al., 2017; Reyes et al., 2017). For depressed and maltreated adolescents already at risk for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors, being verbally abused in their romantic relationships may serve to increase the negative cognitions associated with suicide, such as thoughts of being alone, of being a burden to others, in addition to feelings of hopelessness (Joiner, 2007; Van Orden et al., 2010). Similarly, perpetrating verbal abuse, physically harming, or threatening to harm a partner may result in actual, threatened, or distorted perceptions of abandonment and isolation, all of which may exacerbate suicide risk.

Despite this study’s strengths, there are some limitations. First, although more research is needed with underserved groups, our sample of economically disadvantaged, racially-diverse, not-treatment seeking adolescence with clinically elevated depressive symptoms limits generalizability to other less vulnerable populations. Second, our sample consisted of adolescent females only and despite existing evidence suggesting equivalent ADV subgroups for males, the negative sequelae of dating violence patterns may differ by gender (Reyes et al., 2017). Our study also did not measure all types of dating violence, such as relational violence (e.g., preventing a partner from socializing with friends), and the low endorsement of sexual violence involvement in the current sample prevented its inclusion in the latent class enumeration model, both of which may represent important indicators needed to further differentiate dating violence groups. Our sample size may have also prevented us from finding additional dating violence patterns, such as a victim- and perpetrator-only class found in other studies (Choi et al., 2017; Goncy et al., 2017; Sullivan et al., 2019), although it is consistent with results found in similarly-sized (Reyes et al., 2017) and larger sample studies (Haynie et al., 2013). Finally, despite temporal precedence for examining a model in which a childhood history of maltreatment is associated with adolescent mental health, the current study used retrospective self-report maltreatment data and was correlational in design, thus preventing conclusions about causality.

Implications and Future Directions

Replication of our findings in a longitudinal study is warranted to establish causality for maltreatment predicting self-injurious thoughts and behaviors and to test the moderating effect of subsequent adolescent dating violence on these relationships. Additional longitudinal research is also needed to determine whether stability exists in dating violence class membership, especially since current evidence suggests that dating violence perpetration and victimization increases over time for adolescent females (Goncy, Farrell, & Sullivan, 2018). The current study focused on suicide risk factors among maltreated adolescent females, although some evidence suggests that the impact of child maltreatment on suicide risk may be more robust for male youth (Miller et al., 2013). Additionally, higher rates of suicide were found for males who reported specific types of dating violence, such as the presence of both sexual and physical violence victimization (Vagi et al., 2015), thus potentially indicating that different types of dating patterns may more strongly be linked with suicide risk factors of males, relative to females. The sexual orientation of the romantic partners was not assessed and represents an area in further need of exploration as high rates of adolescent dating violence victimization have been noted in studies of LGBTQ youth and is linked with increased risk for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (Espelage, Merrin, & Hatchel, 2018; Halpern, Young, Waller, Martin, & Kupper, 2004). Finally, future studies are warranted to investigate both the presence and escalation of violence to determine if differences in the rates of behaviors, rather than their presence or absence, distinguish patterns of dating violence and are differentially associated with adolescent mental health.

Overall, we found that the link between maltreatment history and suicidal ideation was stronger for female adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms involved in dating violence, regardless of whether the violence was typified by mutual verbal abuse only or also involved physical abuse and threatening behaviors. This highlights the heightened susceptibility for negative change in mental health present among maltreated adolescents, which is worsened by additional exposure to relational conflict, even after controlling for depressive symptoms. Importantly, dating is a normative part of adolescent development and, although not deterministic, research converges to suggest that these females are at increased risk for involvement in dating violence based on their myriad risk factors (Adams, Handley, Manly, Cicchetti, & Toth, 2019; Capaldi et al., 2012; Hamby et al., 2012; Laporte et al., 2011). Thus, the results of this study underscore the need for more targeted community outreach with such at-risk adolescents for improving awareness about what dating violence looks like as well as its correlates and sequalae, encouraging help-seeking behaviors among adolescents involved in violent romantic relationships, and providing skill-based strategies to help teens appropriately manage romantic conflicts. The means through which this can be accomplished require practical considerations, given that a majority of adolescents do not seek professional assistance when they are involved in unhealthy romantic relationships but instead rely on their friends for advice and support (Ashley & Foshee, 2005).

Potential interventions efforts can target families, as family plays an important role in both dating violence involvement and help-seeking behaviors for adolescents. Witnessing domestic violence, which represents a form of emotional maltreatment, has been related to both the teen’s beliefs about the acceptability of dating violence and to their experience of psychological and/or physical abuse in their own romantic relationships (Karlsson, Temple, Weston, & Le, 2016). Moreover, greater acceptance of dating violence (Karlsson et al., 2016; Temple, Shorey, Tortolero, Wolfe, & Stuart, 2013) and use of violence explained the link between exposure to interparental abuse and teen dating violence (Malik, Sorenson, & Aneshensel, 1997). Greater beliefs about the acceptability of violence is also positively associated with involvement in romantic relationships characterized by different types of violent behaviors (Reyes et al., 2017; Sullivan et al., 2019), and a lower likelihood of seeking support for dating violence from either personal or professional sources (Hedge, Hudson-Flege, & McDonell, 2017). Adolescents with maltreatment histories may be at particular risk for the continuity of dating violence if they are unable to turn to their parents for guidance on how to appropriately prevent or end dating violence. Results from a family-based program to prevent adolescent dating violence found that in-home, self-administered informational and interactive booklets for caregivers and teens helped to improve caregivers knowledge of dating violence and their efficacy in preventing dating violence with their adolescents (Foshee et al., 2012). Additionally, adolescents in the treatment arm were less accepting of dating violence and were less likely to experience physical dating violence compared to their counterparts in the control condition. Application of this intervention to low-income maltreating families may be useful, given the manifold practical and systemic barriers to traditional outpatient service engagement and utilization, such as lack of transportation or distrust of the healthcare system. In particular, providing maltreated teens and their caregivers with a deeper understanding of dating violence behaviors, changing beliefs about the acceptability of interpersonal violence and supporting their use of prosocial conflict resolution strategies is potentially promotive of change in different interpersonal domains for both the child and the caregiver, and may support the parent’s self-efficacy as a competent, empathic caregiver for their adolescent during this important developmental period. Furthermore, promoting skills-based, behavioral approaches to manage conflict and to disengage from an abusive romantic partner is considered a missing but potentially integral component to effectively stopping and preventing dating violence for victims and perpetrators (De La Rue, Polanin, Espelage, & Pigott, 2017; Reyes et al., 2017).

Finally, as our sample was partly recruited from healthcare settings, medical and mental health practitioners who service low-income, high-risk families are in an ideal position to potentially know an adolescent’s maltreatment and mental health histories and to ask about dating violence involvement. For at-risk teens involved and uninvolved in dating violence, psychoeducation about ADV can be provided, in addition to mental health resources to scaffold the teen’s behavioral and emotion regulation. Intervention efforts to promote more adaptive interpersonal skills in at-risk adolescents are critically needed, since both maltreatment and adolescent dating violence have important consequences for the continuity of violence in subsequent relationships with both romantic partners and potential offspring in later years (Adams et al., 2019).

Footnotes

The term “mother” is used throughout the paper; however it is worth noting that for 5% of the adolescents the caregiver was not a mother, but rather a father, grandmother, aunt or another adult caregiver.

References

- Adams TR, Handley ED, Manly JT, Cicchetti D, & Toth SL (2019). Intimate partner violence as a mechanism underlying the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment among economically disadvantaged mothers and their adolescent daughters. Development and Psychopathology, 31(1), 83–93. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418001505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley OS, & Foshee VA (2005). Adolescent help-seeking for dating violence: Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates, and sources of help. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36(1), 25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhouv T, & Muthén B (2007). Wald test of mean equality for potential latent class predictors in mixture modeling. Retrieved November, 9, 2009.

- Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary secondary model. Mplus Web Notes, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bakk Z, & Vermunt JK (2016). Robustness of stepwise latent class modeling with continuous distal outcomes. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 23, 20–31. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.955104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS, Beck AT, Jolly JB, & Steer RA (2005). Beck Youth Inventories—Second edition for children and adolescents manual. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, & Fink L (1998). Childhood trauma questionnaire: A retrospective self-report: Manual: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, … Zule W (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolck A, Croon M, & Hagenaars J (2004). Estimating latent structure models with categorical variables: One-step versus three-step estimators. Political Analysis, 12(1), 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK, & Shortt JW (2007). Observed initiation and reciprocity of physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 101–111. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, & Kim HK (2012). A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 3, 231–280. doi: 10.1037/e621642012-252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HJ, Weston R, & Temple JR (2017). A three-step latent class analysis to identify how different patterns of teen dating violence and psychosocial factors influence mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(4), 854–866. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0570-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D (2013). Annual research review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children–past, present, and future perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54, 402–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02608.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Toth SL (2016). Child maltreatment and developmental psychopathology: A multilevel perspective. Developmental Psychopathology, 1–56. doi: 10.1002/9781119125556.devpsy311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano A, Cella S, & Cotrufo P (2017). Nonsuicidal Self-injury: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 1946–1946. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, & Lanza ST (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences (Vol. 718): John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- De La Rue L, Polanin JR, Espelage DL, & Pigott TD (2017). A meta-analysis of school-based interventions aimed to prevent or reduce violence in teen dating relationships. Review of Educational Research, 87(1), 7–34. doi: 10.3102/0034654316632061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Merrin GJ, & Hatchel T (2018). Peer victimization and dating violence among LGBTQ youth: The impact of school violence and crime on mental health outcomes. Youth violence and juvenile justice, 16(2), 156–173. doi: 10.1177/1541204016680408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito CL, & Clum GA (2002). Social support and problem-solving as moderators of the relationship between childhood abuse and suicidality: Applications to a delinquent population. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 15(2), 137–146. doi: 10.1023/a:1014860024980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez L, Wekerle C, & Goldstein AL (2012). Measuring adolescent dating violence: Development of ‘conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory’short form. Advances in Mental Health, 11(1), 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, & Holt M (2009). Pathways to poly-victimization. Child Maltreatment, 14(4), 316–329. doi: 10.1177/1077559509347012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Elhai JD, Connor DF, & Frueh BC (2010). Poly-Victimization and Risk of Posttraumatic, Depressive, and Substance Use Disorders and Involvement in Delinquency in a National Sample of Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(6), 545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Reyes HLM, Ennett ST, Cance JD, Bauman KE, & Bowling JM (2012). Assessing the effects of Families for Safe Dates, a family-based teen dating abuse prevention program. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51(4), 349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman LH, Weierich MR, Hooley JM, Deliberto TL, & Nock MK (2007). Child maltreatment, non-suicidal self-injury, and the mediating role of self-criticism. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(10), 2483–2490. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncy EA, Farrell AD, & Sullivan TN (2018). Patterns of change in adolescent dating victimization and aggression during middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 501–514. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0715-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncy EA, Sullivan TN, Farrell AD, Mehari KR, & Garthe RC (2017). Identification of patterns of dating aggression and victimization among urban early adolescents and their relations to mental health symptoms. Psychology of violence, 7, 58. doi: 10.1037/vio0000039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray HM, & Foshee V (1997). Adolescent dating violence: Differences between one-sided and mutually violent profiles. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 12, 126–141. doi: 10.1177/088626097012001008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Young ML, Waller MW, Martin SL, & Kupper LL (2004). Prevalence of partner violence in same-sex romantic and sexual relationships in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35(2), 124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S, Finkelhor D, & Turner H (2012). Teen dating violence: Co-occurrence with other victimizations in the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (NatSCEV). Psychology of violence, 2(2), 111. doi: 10.1037/a0027191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C (2003). Interpersonal stress and depression in women. Journal of Affective Disorders, 74, 49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00430-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley ED, Adams TR, Manly JT, Cicchetti D, & Toth SL (2018). Mother–daughter interpersonal processes underlying the association between child maltreatment and adolescent suicide ideation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Farhat T, Brooks-Russell A, Wang J, Barbieri B, & Iannotti RJ (2013). Dating violence perpetration and victimization among US adolescents: Prevalence, patterns, and associations with health complaints and substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedge JM, Hudson-Flege MD, & McDonell JR (2017). Promoting informal and professional help-seeking for adolescent dating violence. Journal of community psychology, 45(4), 500–512. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SM, Garcia M, Kemp K, Mazure CM, & Sinha R (2005). A gender specific psychometric analysis of the early trauma inventory short form in cocaine dependent adults. Addictive Behaviors, 30, 847–852. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T (2007). Why people die by suicide: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson ME, Temple JR, Weston R, & Le VD (2016). Witnessing interparental violence and acceptance of dating violence as predictors for teen dating violence victimization. Violence Against Women, 22(5), 625–646. doi: 10.1177/1077801215605920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, … Ryan N (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 980–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC (2003). Epidemiology of women and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 74, 5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00426-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte L, Jiang D, Pepler DJ, & Chamberland C (2011). The relationship between adolescents’ experience of family violence and dating violence. Youth & Society, 43, 3–27. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Sorenson SB, & Aneshensel CS (1997). Community and dating violence among adolescents: Perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health, 21, 291–302. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00143-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MS, Dykxhoorn J, Afifi TO, & Colman I (2016). Child abuse and the prevalence of suicide attempts among those reporting suicide ideation. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 51(11), 1477–1484. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1250-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AB, Esposito-Smythers C, Weismoore JT, & Renshaw KD (2013). The relation between child maltreatment and adolescent suicidal behavior: a systematic review and critical examination of the literature. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16, 146–172. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0131-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, & Muthén B (2017). 1998–2017. Mplus User’s Guide Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, … Gluzman S (2008). Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 192(2), 98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes HLM, Foshee VA, Chen MS, & Ennett ST (2017). Patterns of dating violence victimization and perpetration among Latino youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 1727–1742. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0621-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Peta I, McPherson K, Greene A, & Li S (2010). Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS-4). Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 9, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, & Hathaway JE (2001). Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. Jama, 286(5), 572–579. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TN, Goncy EA, Garthe RC, Carlson MM, Behrhorst KL, & Farrell AD (2019). Patterns of Dating Aggression and Victimization in Relation to School Environment Factors Among Middle School Students. Youth & Society, 1–25. doi:0044118X19844884 [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Shorey RC, Tortolero SR, Wolfe DA, & Stuart GL (2013). Importance of gender and attitudes about violence in the relationship between exposure to interparental violence and the perpetration of teen dating violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(5), 343–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2017). Child Maltreatment 2017. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment

- Vagi KJ, Olsen EOM, Basile KC, & Vivolo-Kantor AM (2015). Teen dating violence (physical and sexual) among US high school students: Findings from the 2013 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. JAMA Pediatrics, 169, 474–482. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, & Joiner TE Jr (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological review, 117(2\), 575. doi: 10.1037/a0018697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Gelfand A, Katon WJ, Koss MP, Von Korff M, Bernstein D, & Russo J (1999). Adult health status of women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect. The American journal of medicine, 107, 332–339. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00235-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wekerle C, Grasley C, & Straatman A-L (2001). Development and validation of the conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory. Psychological assessment, 13, 277. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.13.2.277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Scott K, Wekerle C, & Pittman A-L (2001). Child maltreatment: Risk of adjustment problems and dating violence in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 282–289. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200103000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra ML, Espelage DL, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Korchmaros JD, & Boyd D (2016). Lifetime Prevalence Rates and Overlap of Physical, Psychological, and Sexual Dating Abuse Perpetration and Victimization in a National Sample of Youth. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(5), 1083–1099. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0748-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]