Abstract

Background:

A growing number of migrants experience precarious housing situations worldwide, but little is known about their health and housing experiences. The objective of this study was to understand the enablers and barriers of accessing fundamental health and social services for migrants in precarious housing situations.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic review of qualitative studies. We searched the databases of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Scopus, Web of Science, Social Sciences, Canadian Business & Current Affairs and Sociological Abstracts for articles published between Jan. 1, 2007, and Feb. 9, 2020. We selected studies and extracted data in duplicate, and used a framework synthesis approach, the Bierman model for migration, to guide our analysis of the experiences of migrant populations experiencing homelessness or vulnerable housing in high-income countries. We critically appraised the quality of included studies using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist and assessed confidence in key findings using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (GRADE-CERQual) approach.

Results:

We identified 1039 articles, and 18 met our inclusion criteria. The studies focused on migrants from Asia and Africa who resettled in Canada, Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom and other European countries. Poor access to housing services was related to unsafe housing, facing a family separation, insufficient income assistance, immigration status, limited employment opportunities and lack of language skills. Enablers to accessing appropriate housing services included finding an advocate and adopting survival and coping strategies.

Interpretation:

Migrants experiencing homelessness and vulnerable housing often struggle to access health and social services; migrants may have limited proficiency with the local language, limited access to safe housing and income support, and ongoing family insecurities. Public health leaders could develop outreach programs that address access and discrimination barriers.

PROSPERO Registration:

CRD42018071568

Worldwide, more than 272 million people are classified as “international migrants”.1 Migrant populations include refugees, asylum seekers, displaced persons and immigrants who move from their country of residence to another.2,3 Literature suggests that homelessness may be prevalent among migrants to different countries.4–6 Within North America, evidence highlights a substantial movement of undocumented migrants from the United States into Canada.7

Refugees and other migrants who are precariously housed may couch surf, or live in motels and other short-term rentals. When these options fail, they turn to temporary homeless shelters.8,9 In contrast to government-assisted refugee shelters, homeless shelters lack language and cultural food resources, and other health, education and employment resettlement infrastructure.8 Forced displacement and marginalization can create additional challenges in securing safe and stable housing for migrants,10 with many experiencing homelessness at some point in their resettlement process. The magnitude of visible or hidden migrant homelessness is largely unknown and what little evidence exists is of low quality, which limits the development of policies, programs and services that address homelessness among migrants.

Field research suggests that the risk of migrant homelessness increases with cuts to social programs, persistent health issues, poverty, lack of affordable housing, unrecognized education credentials, unemployment, delays in obtaining work permits, deinstitutionalization and lack of discharge planning.11 Mobile migrants are also at risk for frostbite, infectious diseases, soft-tissue infections, traumatic injuries and chronic illnesses (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease).12,13 Furthermore, migrants may suffer from common mental illnesses, including posttraumatic stress disorder and depression.14 Migrant populations may also struggle with food insecurity and impaired access to health and social services.15–17

The objective of this systematic review was to understand the enablers and barriers of accessing fundamental health and social services for migrants who found themselves in precarious housing situations.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a systematic review according to a registered protocol (PROSPERO CRD42018071568; Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/2/E681/suppl/DC1).19 We reported our findings according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline.20

Search strategy

With the assistance of an information scientist librarian, we developed a search strategy using a combination of subject headings and keywords, including “migrant,” “refugee,” “asylum seeker,” “homeless,” “unsheltered” and “street.” The primary search strategy is presented in Appendix 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/2/E681/suppl/DC1. We used this strategy, and its translated versions, to systematically search the databases of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Scopus, Web of Science, Social Sciences, Canadian Business & Current Affairs and Sociological Abstracts for relevant studies from 2007 to Feb. 9, 2020. We did not apply any filters or language restrictions. We did not systematically search for additional studies in reference lists or grey literature.

We originally searched bibliographical databases from the date of their inception; however, we soon recognized that evidence published since 2007 represents a reflection of a scholarly evolution in the field of migration and global health research, characterized by an exponential increase in the rate of research articles published in peer-reviewed journals.18 As a result, we decided to deviate from protocol and restrict the date of publication from 2007 onward at the full-text screening phase of the review.

Eligibility criteria

We included studies in our systematic review if they used a qualitative or mixed method design and were published between 2007 and 2020, in any language. We focused on studies whose participants were refugees, asylum seekers or undocumented migrants who were presently residing in high-income countries, as defined by the World Bank.21 We restricted our studies to high-income settings, given the relative homogeneity in how migrants integrate into the labour market22 and the similar challenges they face when accessing health and social welfare services.23,24 We included studies that reported on the barriers and facilitators that migrants face when accessing housing or shelter, and their health and well-being. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria, and a detailed description of study populations, interventions, controls and outcomes can be found in Appendix 3, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/2/E681/suppl/DC1.

Study selection and data collection

Four team members (H.K., C.M., A.S., Q.A.) screened and selected titles, abstracts and full-text articles, independently and in duplicate. At the full-text screening stage, we limited articles to those published between Jan. 1, 2007, and Feb. 9, 2020, as noted earlier. All conflicts were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer (K.P.).

After study selection, we developed a standardized data extraction sheet that included study methodology, participant characteristics and contextual findings, including labour market conditions, immigration policies, social networks, neighbourhood characteristics, discrimination, income, education and language. We piloted the data extraction form to ensure relevancy (H.K., G.K.). Five reviewers (H.K., G.K., O.M., A.S., Q.A.) extracted data independently and in duplicate, and any conflicts were resolved with the help of a third reviewer (K.P.).

Data analysis

We assessed the methodological quality of included articles using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for qualitative studies25 (H.K., G.M., O.M., A.S.) (Appendix 4, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/2/E681/suppl/DC1). We used the best-fit framework method as a systematic and flexible approach to analyzing the qualitative data.26–28 Framework analysis is a 5-stage process that includes familiarization with the data, identifying a thematic framework, indexing (applying the framework), charting and mapping, and interpretation.29 We selected the Bierman model for migrant health as our framework.30 The Bierman model is a conceptual framework that considers the intersection of social determinants of health, gender equity, racial and ethnic disparities in health, and the migration experience.31

One reviewer (H.K.) coded the data into the domains of the Bierman model using a matrix spreadsheet to facilitate analysis; a second reviewer (K.P.) verified the coding. The review team (H.K., O.M., A.S., K.P.) identified and interpreted key findings through discussion with the review team. For the purposes of this review, we defined a review finding as an analytic output from our qualitative evidence synthesis that describes a phenomenon or an aspect of a phenomenon, based on data (participant quotations or author observation) from primary studies.32

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (GRADE-CERQual) approach.33,34 This approach evaluates findings on 4 criteria: methodological limitations of included studies supporting a review finding, the relevance of included studies to the review question, the coherence of the review finding and the adequacy of the data contributing to a review finding (Table 1).

Table 1:

Components of GRADE-CERQual assessments33

| Component | Definition |

|---|---|

| Methodological limitations | The extent to which problems were identified in the conduct of the primary studies that contributed to the evidence for a review finding |

| Relevance | The extent to which the primary studies supporting a review finding are applicable to the context specified in the review question |

| Coherence | The extent to which a review finding is based on a pattern of data that is similar across multiple individual studies and/or incorporates (compelling) explanations for any variations across individual studies |

| Adequacy of data | An overall determination of the degree of richness and/or scope of the evidence and of the quantity of data supporting a review finding |

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was not required for this study.

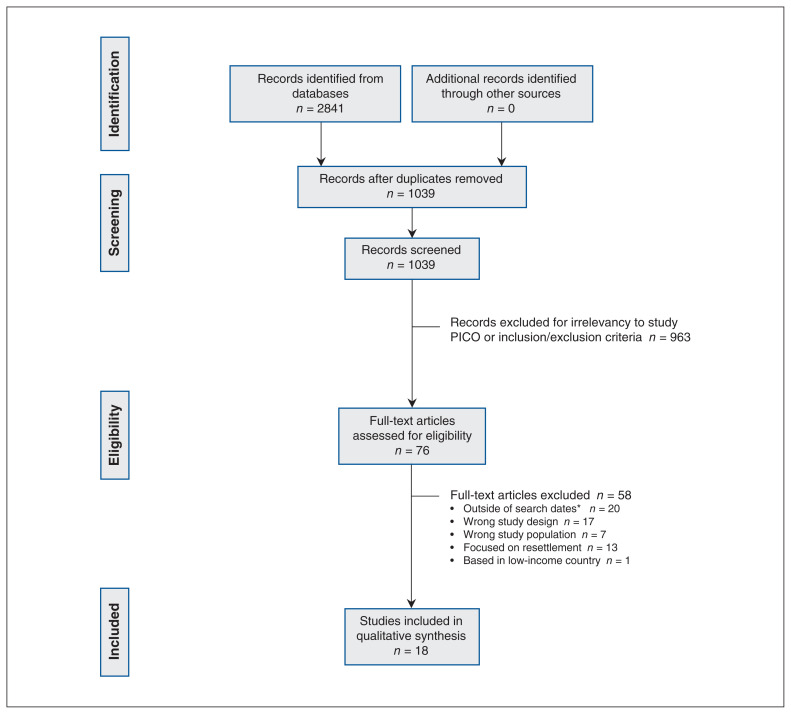

Results

Our search initially identified 1039 unique articles; however, after the initial removal of duplicates, we found 754 additional duplicate citations. We further screened articles to exclude low-income countries, and study populations and designs that did not meet inclusion criteria. We included 18 studies in our analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Flow chart based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines.

Note: PICO = population, intervention, comparison, outcomes. *We originally searched bibliographical databases from the date of their inception; however, we soon recognized that evidence published since 2007 represents scholarly evolution in the field of migration and global health research.18 As a result, we deviated from protocol and restricted date of publication from 2007 onward at the full-text screening phase of the review.

Study characteristics

Eight studies focused specifically on refugees,6,35–41 and the remaining 10 studies considered the broader migrant populations, including immigrants, newcomers or refugees.42–51 Resettlement countries included Canada (n = 9), Australia (n = 4), Belgium (n = 1), Denmark (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), the United Kingdom (n = 1) and the US (n = 1). All included studies followed a naturalistic inquiry approach, except for 3 that had a comparison group.45,48,49 The characteristics of included studies and the methodological quality of studies are found in Table 2.

Table 2:

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Country | Design | Population | Intervention | Focus | CASP risk to rigour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Couch 201740 | Australia | Semistructured interviews | n = 24 (10 women and 14 men) aged 15 to 24 years | Natural history study, no intervention | To open up new areas of social enquiry and address the limited research focusing on refugee young people and homelessness. | Low |

| Couch 201139 | Australia | Face-to-face dialogic interviews | n = 9 (5 women and 4 men) aged 19 to 25 years | Natural history study, no intervention | To focus on the voices of refugee young people experiencing homelessness. | Medium |

| Couch 201235 | Australia | Interviews | n = 9 (5 women and 4 men) aged 19 to 25 years | Natural history study, no intervention | To evaluate the perception of refugee young people experiencing homelessness regarding service delivery and provision. | Low |

| D’Addario et al. 200744 | Canada | Semistructured interviews and surveys | 12 semistructured interviews, 36 individual interviews and 554 surveys | Natural history study, no intervention | To evaluate the role of social capital in housing trajectories of immigrants, with particular attention to the experiences of refugee claimants. | Low |

| Dwyer and Brown 200838 | UK | Interviews and mini focus group | n = 23 (13 men and 10 women) aged 27 to 54 years | Natural history study, no intervention | To outline the tiering of housing entitlement that exists within the generic population of dispersed forced migrants, and its role in rendering migrants susceptible to homelessness. | Low |

| Flatau et al. 20156 | Australia | A cross-sectional survey, focus group discussions and transcent walks | n = 20 (15 men, 4 women and 1 unknown), 19 of whom were aged between 22 and 51 years | Natural history study, no intervention | To report on the findings of the Refugees and Homelessness Survey that was completed with refugees experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness. | Low |

| Im 201137 | US | In-depth individual interviews | n = 26 (4 men and 22 women), mean age 36.6 years | Natural history study, no intervention | To explore the mental health of refugee families in the socioecological contexts of displacement and homelessness, and to investigate stressors and coping in relation to transition of resources, including social capital of refugee families. | Low |

| Kissoon 201036 | Canada | Interviews | n = 34 migrants (18 women, 16 men), 27 key informants from nongovernmental organization, legal and health sectors. | Natural history study, no intervention | To focus on the refugee determination system to draw attention to the intersection of illegality and vulnerability to persecution, and to identify the characteristics and homelessness experiences of nonstatus or undocumented migrant participants in Vancouver and Toronto. | Medium |

| Mostowska 201342 | Norway | Narrative interviews and informal conversations | n = 40 aged from 23 to 62 years, most between 35–55 years | Natural history study, no intervention | To discuss the results of fieldwork conducted among migrants of Polish descent experiencing homelessness in Oslo, Norway, with focus on the social networks that are a part of the migrants’ social capital. | Medium |

| Mostowska 201243 | Belgium | Field notes, informal conversations and individual interviews | n = 45 (6 women, 39 men) people of Polish descent who had been sleeping rough or reported an episode of rough sleeping in the recent past. Thirteen of the men were older than 55 years, and 16 people were younger than 35 years | Natural history study, no intervention | To acknowledge homelessness among migrants of Polish descent in Brussels and analyze their narratives using Julian Wolpert’s concept of “place utility” to confront the way they talk about their adaptation to the environment with the risks and opportunities they attach to staying in Brussels and to their possible return migration to Poland. | High |

| Paradis et al. 200845 | Canada | Interviews | n = 91 women-led homeless families | Immigrant and refugee families v. Canadian-born families experiencing homelessness. Each woman was interviewed 3 times over the course of a year. | To understand homelessness among immigrant and refugee families to improve public policy and programs for these families. | Medium |

| Sjollema et al. 201246 | Canada | Semistructured interviews | n = 26 women, most aged between 20 to 40 years | Natural history study, no intervention | To provide a context for understanding homelessness among newcomer women and to summarize the history of the found poem in a variety of disciplines with an emphasis on “social work and the arts” context. | Medium |

| Walsh et al. 201547 | Canada | Semistructured, open-ended interviews | n = 26 women aged from 22–64 years | Natural history study, no intervention | To explore housing insecurity among newcomer women to Montréal, Canada. | Low |

| Polillo and Sylvestre 201948 | Canada | In-depth interviews | n = 36 (23 foreign-born families, 13 Canadian-born families). Mean age for the foreign-born sample was 38.27 years (SD 9.57); 73.9% of the foreign-born sample are women | Foreign-born v. Canadian-born families | To investigate the experiences of foreign-born families in the 4 years before becoming homeless. | Low |

| Polillo et al. 201749 | Canada | Interviews with adult heads of families | n = 75 (Canadian-born interviewees: 6 men, 20 women, mean age 33.8 years; foreign-born: 14 men, 34 women, mean age 36.8 years) | Foreign-born v. Canadian-born people | To evaluate the health of foreign-born families staying in the emergency shelter system in Ottawa, and to compare their experiences to Canadian-born families who are also living in shelters. | Low |

| St-Arnault and Merali 201841 | Canada | Interviews | n = 19 (11 women, 8 men), aged 29 to 73 years, mean age 39 years | Natural history study, no intervention | To investigate pathways out of homelessness among a mixed sample of adult refugees who had experienced absolute or relative homelessness after their arrival in Canada, but who eventually became adequately settled in one of Canada’s large urban centres in Alberta. | Low |

| Ravnbøl 201751 | Denmark | Semistructured interviews | n = 40 | Natural history study, no intervention | To address health concerns and access to health services among migrants of Roma descent in the European Union, from a perspective of Romanian Roma who live in homelessness in Copenhagen. | Medium |

| Hanley et al. 201850 | Canada | Semistructured, open-ended interviews | n = 26 women aged 20 to 65 years | Natural history study, no intervention | To explore how health intersects with the experience of housing insecurity and homelessness, specifically for migrant women. | Low |

Note: CASP = Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, SD = standard deviation.

The Bierman model (Appendix 5, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/2/E681/suppl/DC1) provided conceptual categories that we used to map and characterize our qualitative findings. In doing so, we identified 8 distinct findings from the included studies, summarized in Table 3. The confidence in the findings ranged from very low to moderate, with 4 of the findings being of moderate confidence. Appendix 6, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/2/E681/suppl/DC1, provides a detailed description of the findings. Of note, several factors from within the Bierman model had limited data available during the extraction process, including political environment, education and other factors.

Table 3:

Summary of findings

| Framework level | Key findings | GRADE-CERQual assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence in the evidence | Explanation | ||

| Discrimination | Systemic racism: Refugees experienced individual and systemic racism, which exacerbated housing instability. Many refugees felt they were turned away from housing and emergency shelters because of their ethnicity, use of welfare cheques, history of trauma, language of origin, temporary resident status and the presence of children. | Low | Moderate concerns for methodological limitations and adequacy, and no-to-minor concerns for coherence and relevance. |

| Mental health | Mental health concerns: Lived experience of trauma and housing insecurity resulted in persistent psychological distress and mental health concerns. | Moderate | Very minor concerns for methodological limitations, no-to-very minor concerns for coherence, relevance and adequacy. |

| Social networks and support | Finding an advocate: Refugees who sought a culturally familiar community advocate were able to increase their social capital. Advocates included settlement counsellors and cultural brokers. These advocates were able to help refugees transition out of homelessness by providing social support, a place to stay and other resources. | High | Minor concerns for methodological limitations, no-to-very minor concerns for coherence, relevance and adequacy. |

| Services: health and housing | Poor access to services: Refugees and other migrants, particularly undocumented migrants, failed asylum seekers and those with humanitarian protection, are often unaware of support services and find them difficult to access and navigate. | Moderate | Minor concerns for methodological limitations, no-to-very minor concerns for coherence, relevance and adequacy. |

| Unsafe housing: Refugees and other migrants perceived the housing options available to them as unsafe, poorly managed and unaffordable. | High | Minor concerns for methodological limitations, very minor-to-minor concerns for relevance and no-to-very minor concerns for coherence and adequacy. | |

| Family structure | Facing a family separation: Several vulnerably housed refugees expressed difficulties learning a new culture, and parents struggled with the ability of their children to balance a new culture and the culture of their country of origin. This family conflict led to a loss of family support, which is a protective factor against homelessness. | Low | Moderate concerns for methodological limitations and relevance, no-to-very minor concerns for coherence and adequacy. |

| Income | Insufficient income assistance: Refugees and other migrants reported strained finances and inadequate financial support that led to difficulty meeting basic needs, housing insecurity and food instability. | Low | Moderate concerns for methodological limitations and relevance, no-to-very minor concerns for coherence and adequacy. |

| Immigration status | Impact of immigration status: Compared with status migrants, nonstatus migrants faced substantial barriers, such as limited rights to welfare, prohibition from taking up paid employment and rejection from shelter access. | Low | Serious concerns for methodological limitations, moderate concerns for relevance and no-to-very minor concerns for coherence and adequacy. |

| Language | Lack of language skills impeding access: Limited language skills among refugees impeded their ability to access most services, including housing services, and limited their social capital and connections beyond their original community. | Moderate | Moderate concerns for methodological limitations, no-to-minor concerns for coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Outlier | Adopting survival and coping strategies: Refugees and other migrants who faced insecure housing instability adopted survival and coping strategies that helped them to advocate for resources and develop a sense of belonging in their new community. | Moderate | Moderate concerns for relevance, no-to-minor concerns for coherence, relevance and adequacy. |

Note: GRADE-CERQual = Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative.

Barriers to accessing housing services

Interpersonal racism

Two common barriers to accessing stable and secure housing for migrants were discrimination and stigmatization, often based on race, gender, socioeconomic status, language of origin, housing situation, trauma history and number of children (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: low).6,39,46,47 For example, one migrant stated, “Every time I would call an advert[isement], I would call asking for a house and they would ask, ‘Oh, you have an accent. Where do you come from?’ When I told them I am from Africa, well, the apartment was taken.”47

Mental health concerns

The combined impact of the past trauma experienced by migrants and their vulnerable housing situations contributed to mental health concerns,6,36,39,40,50 often resulting in sleep problems, loss of appetite and anxiety (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: moderate).37 For example, 1 study reported a migrant feeling “seriously stressed” about his homeless status, affecting his mental health.6

Poor access to services

Refugees and other migrants are often unaware of support services and find them difficult to access and navigate (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: moderate).48,51 For example, one migrant in the UK stated, “We are going every time to social services. [Asking] Where is [private housing provider]? Where is Refugee Council? We didn’t know nothing.”38 Another stated, “It was just presumed that I knew where to go, that I understood the system.”40 Furthermore, migrants who were unfamiliar with services would not access emergency or transitional accommodation. Some migrants did not identify as homeless, and would not seek out services.40

Unsafe housing

Refugees and other migrants perceived the housing options available to them as unsafe, poorly managed and unaffordable. Furthermore, housing programs were often described as strict, controlling, substandard, and in some cases, dangerous, especially by younger populations (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: high).35,38–40,48 In one UK study, several of the respondents described the weaknesses in the National Asylum Support Services housing system as poor quality, overcrowded and lacking effective orientation and services.38

Facing family conflict and intercultural tensions

Several vulnerably housed refugees expressed difficulties learning a new culture, and parents also struggled with the ability of their children to balance a new culture and the culture of their country of origin (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: low).40 At times, parents considered their child’s acquisition of the English language, Western fashion or new social life as abandonment of their traditional cultural beliefs and values (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: low).39 The tension between 2 different cultures often resulted in conflicts and tensions in family support systems (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: low).39

Insufficient income assistance

Refugees and other migrants reported strained finances and inadequate financial support that led to difficulty meeting basic needs, housing insecurity and food instability (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: low).40,45–48 In one study, nearly all of the respondents had had trouble finding a new place to live because accommodation was too expensive.47

Impact of immigration status

Compared with status migrants, nonstatus migrants faced substantial barriers, such as limited rights to welfare, prohibition from taking up paid employment and rejection from shelter access (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: low).36,38,45,51 Ravnbøl and colleagues51 discussed how Danish law prevented migrants from registering as workers in the European Union, and because they did not have a Danish social security number, no one would hire them or rent them a place to live.

Lack of language skills impeding access

Limited language skills negatively affected accessibility to health and social services for migrants, such as housing programs (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: moderate).51 In a study by Couch and colleagues,39 a young migrant in a rooming house described the challenges of renting with limited English skills, “My English is a problem because I do not always understand the rules of renting a place and may get evicted because I do not understand the rules. Or sometimes notices are placed in the building for people to come together and I can’t be involved because I can’t read the sign.” Mostowska and colleagues considered language the most important resource for migrants to create and expand their social networks beyond their cultural community;43 limited language skills can worsen the feeling of being isolated from others (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: moderate).44

Limited employment opportunities

Difficulty obtaining employment was frequently reported among migrants as a barrier to stable and secure housing. Being denied work or meaningful opportunities can inhibit and affect migrants’ pride in being active citizens in their resettlement country, as well as affect their personal sense of accomplishment and meaning (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: moderate).37,39,47 Dreams of owning a house, studying or working as citizens of a new country were difficult to achieve: “I am so many steps away, miles away from having anything like the Australians have.”40 Some migrants noted limited personal, family and cultural resources that further exacerbated the ability to find stable and meaningful employment.

Enablers to accessing housing services

Finding an advocate

Refugees who sought a culturally familiar, community advocate were able to increase their social capital, which is recognized as the network of social relations that can provide people and groups with access to resources and support (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: high).39–41,47,48 Advocates included settlement counsellors and cultural brokers. These advocates were able to help refugees transition out of homelessness by providing social support, a place to stay and other resources.41,48 One study reported that when a pregnant woman was faced with impending homelessness, she scanned the public phone directory, looking for Sudanese names from her community.39 Similarly, another woman found assistance in housing after approaching a stranger on the street who spoke her first language.47

Adopting survival and coping strategies

Refugees and other migrants who faced insecure housing instability adopted survival and coping strategies that helped them to advocate for resources and develop a sense of belonging in their new community. The survival and coping strategies ranged from faith-based coping to coping using substance use (GRADE-CERQual confidence level: moderate).39–41,46,50

Interpretation

A comprehensive understanding of background characteristics that influence the health and well-being of patients is a prerequisite to delivering equitable health care.52,53 Two such characteristics that are hypothesized to increase vulnerability and decrease access to services are homelessness and migration status.4,54 We explored the best available qualitative evidence on the enablers and barriers of accessing fundamental health and social services for migrants who found themselves in precarious housing situations.

Our findings suggest that migrants experiencing homelessness often struggle to meet their housing and health needs and to access essential services because of interpersonal racism, limited proficiency with the local language, lack of financial stability and family tensions, leading to worsened mental health conditions. To overcome these barriers, migrants experiencing homelessness often resort to different coping strategies and rely on community advocates to increase their social capital. Even though implementing interpretation services can mitigate linguistic barriers and ensure the provision of equitable care for migrant patients,55,56 health care practitioners in Canada need to adopt a more holistic approach to providing care for these populations, one that addresses their housing situation and the barriers that further increase their housing instability and vulnerability, such as family tensions and financial instability.

Migrants described experiencing interpersonal racism when attempting to access health and social services. Xenophobia, racism, and attitudes and behaviours that lead to civic exclusion of others based on a foreign cultural or national identity are upstream factors that produce discrimination and poor health outcomes for migrants.57 Interpersonal incidents of racism are an attack on communities, rather than just individuals.58,59 Indeed, acts of racism are reflections of historical legacies of colonialism and domination,59 which reinforce disempowerment and structural violence. Structural violence describes the social structures that prevent individuals and entire populations from reaching their full potential.60 Structural violence continues to serve as a challenge to providing health care for marginalized populations,61,62 depriving patients of their right to receive equitable services, and increasing the social gradient of how beneficial such services tend to be.53 Even though discrimination has been found to sever trustworthy connections between the general homeless population and their health care providers,63 our findings suggest that this problem is further aggravated when patients who are homeless also have a migration history. In Canada, primary health care practitioners can effectively address their patients’ experiences of interpersonal racism by employing trauma-informed care in its core values and principles.64

Past trauma was found to worsen the mental health conditions of refugees and other migrants. The literature is abundant with evidence linking premigration and migration exposures of trauma and violence to the initiation or exacerbation of common mental health conditions, such as major depressive disorders, generalized anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorders.14,65 In Canada, the literature highlights a trend of limited access and uptake of mental health services by different migrant populations.66,67 With the scarcity of mental health screening initiatives,68 and the discontinuity of mental health care after resettlement,69 migrants find themselves in need of scaled-up mental health services that could be delivered in their communities.70

Moreover, homelessness after resettlement was a fundamental component that worsened many mental health conditions among migrants. This finding suggests that homelessness is not only the consequence of poor mental health, but also a predictor of poor mental health. Primary health care practitioners in Canada now have an evidence-based guideline to address homelessness as the root for many morbidities and to initiate care for patients experiencing homelessness, including migrants, using upstream and longitudinal interventions.71

It is important to develop and evaluate public health responses for migrants who are homeless or vulnerably housed, especially undocumented migrants. Advances in universal access to health services72 and social accountability in medical schools73 could be matched with policy changes to ensure health equity for homeless migrants. Public health could play a role in raising awareness of these priority populations and developing programs and policies that address access and discrimination barriers, such as antiracist housing policies, migrant-sensitive mental health supports in shelters and migrant-specific shelters. Indeed, public health research can deepen our understanding of the values, attitudes and perceptions of migrants regarding housing, and can have a role in improving outcomes of the social determinants of health.

We evaluated the enablers and barriers of accessing health and social services among a population with lived experience of homelessness. We followed systematic and transparent review methodology to ensure we identified the best available evidence on this phenomenon. As a result, we included studies of vulnerable migrants from diverse geographic regions around the world. Furthermore, we used the GRADE-CERQual methodology to rate the confidence in our findings.

Limitations

We did not use a Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS),74 which could have guided and improved the search strategy. We did not conduct a grey literature search, nor did we search any reference lists. A protocol deviation is also further detailed in Appendix 7, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/2/E681/suppl/DC1. Furthermore, our findings are constrained to the data provided by the interviews and participants within the published primary studies. For example, most participants spoke English, and we recognize that language is an important additional barrier to resources.

Only a small number of participants were undocumented migrants, an important subgroup of this vulnerable population. More subgroup analyses, such as from youth or the recent Syrian refugees, would be important to better understand these specific populations in the future. Most included articles did not describe in detail the relationship between the researcher and the participant which, if not addressed appropriately, could introduce concerns of interviewer and social desirability biases and jeopardize the trustworthiness of qualitative evidence from primary studies. Lastly, we tried to ensure that our findings and considerations were applicable to the Canadian context, which required contextualization and judgments on the relevance of included studies conducted outside of Canada. This process, however, was not always feasible given reporting limitations on the primary-study level.

Conclusion

We highlighted the challenges that refugees and other migrants face after resettlement and when experiencing homelessness. Discrimination and xenophobia were recurrent themes described as both a cause and a consequence of unsafe and insecure housing. An important finding was the limited research available on undocumented migrants experiencing homelessness. Vulnerable housing was often linked to family separation, poor access to services and limited income and employment. Migrants may also face language, cultural and immigration status barriers, and they may benefit from field advocates and personal survival strategies. These findings warrant physician vigilance and public health responses.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Harneel Kaur and Kevin Pottie conceived and designed the work. All authors contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. Harneel Kaur, Ammar Saad, Olivia Magwood, Christine Mathew and Kevin Pottie drafted the manuscript. All of the authors revised it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data sharing: The authors used publicly available data for the analysis in this study.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/2/E681/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.McAuliffe M, Ruhs M, editors. World Migration Report 2020. Geneva: International Organization for Migration; 2019. pp. 1–477. Available: www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/wmr_2020.pdf. accessed 2020 Nov. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McAuliffe M, Ruhs M, editors. World Migration Report 2018. Geneva: International Organization for Migration; 2017. [accessed 2020 Nov. 16]. pp. 1–347. Available: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2018_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gushulak BD, Pottie K, Roberts JH, et al. Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health. Migration and health in Canada: health in the global village. CMAJ. 2011;183:E952–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pleace N. Immigration and homelessness. In: O’Sullivan E, editor. Homelessness Research in Europe: Festschrift for Bill Edgar and Joe Doherty. Brussels (Belgium): FEANTSA; 2011. pp. 143–62. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzpatrick S, Johnsen S, Bramley G. Multiple exclusion homelessness amongst migrants in the UK. Eur J Homelessness. 2012;6:31–58. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flatau P, Smith J, Carson G, et al. The housing and homelessness journeys of refugees in Australia. In: Badenhorst A, editor. AHURI Final Report No. 256. Melbourne (AU): Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute; 2015. [accessed 2017 Sept 1]. pp. 1–110. Available: www.ahuri.edu.au/publications/projects/p82015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keung N. Refugee system in need of overhaul, report says. Toronto Star. 2018. Jun 26, [accessed 2018 Aug 1]. Available: www.thestar.com/news/gta/2018/06/26/refugee-system-in-need-of-overhaul-report-says.html.

- 8.Grant T. Wave of asylum seekers floods Toronto’s shelters. The Globe and Mail. 2018. Jun 20, [accessed 2018 Aug 1]. updated 2018 June 22. Available: www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-in-toronto-asylum-seekers-hope-to-carve-out-a-new-home/

- 9.Gaetz S, Barr C, Friesen A, et al. Canadian definition of homelessness. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness; 2012. [accessed 2018 June 17]. Available: www.homelesshub.ca/resource/canadian-definition-homelessness. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pottie K, Martin JP, Cornish S, et al. Access to healthcare for the most vulnerable migrants: a humanitarian crisis. Confl Health. 2015;9:16. doi: 10.1186/s13031-015-0043-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asanin J, Wilson K. “I spent nine years looking for a doctor”: exploring access to health care among immigrants in Mississauga, Ontario, Canada”. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1271–83. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang SW, Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, et al. Mortality among residents of shelters, rooming houses, and hotels in Canada: 11 year follow-up study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee TC, Hanlon JG, Ben-David J, et al. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in homeless adults. Circulation. 2005;111:2629–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirmayer LJ, Narasiah L, Munoz M, et al. Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health (CCIRH) Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: general approach in primary care. CMAJ. 2011;183:E959–67. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, et al. Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2011;183:E824–925. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goel R, Bloch G, Caulford P. Waiting for care: effects of Ontario’s 3-month waiting period for OHIP on landed immigrants. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:e269–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swinkels H, Pottie K, Tugwell P, et al. Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health (CCIRH) Development of guidelines for recently arrived immigrants and refugees to Canada: Delphi consensus on selecting preventable and treatable conditions. CMAJ. 2011;183:E928–32. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sweileh WM, Wickramage K, Pottie K, et al. Bibliometric analysis of global migration health research in peer-reviewed literature (2000–2016) BMC Public Health. 2018;18:777. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5689-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaur H, Mathew C, Mayhew A, et al. Understanding the health and homeless experiences of vulnerably housed refugees and other migrant populations: a systematic review using GRADE CERQual. Prospero 2018 CRD42018071568. National Institute for Health Research; 2017. [accessed 2020 Mar. 4]. Available: www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=71568. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Bank country and lending group. Washington (DC): The World Bank; [accessed 2020 Mar. 4]. Available https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brell C, Dustmann C, Preston I. The labor market integration of refugee migrants in high-income countries. J Econ Perspect. 2020;34:94–121. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandenberger J, Tylleskär T, Sontag K, et al. A systematic literature review of reported challenges in health care delivery to migrants and refugees in high-income countries - the 3C model. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:755. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7049-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CASP checklists. Oxford (UK): Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP); [accessed 2017 Dec 1]. Available https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carroll C, Booth A, Leaviss J, et al. “Best fit” framework synthesis: refining the method”. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Booth A, Carroll C. How to build up the actionable knowledge base: the role of “best fit” framework synthesis for studies of improvement in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:700–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spencer L, Ritchie J. Analyzing Qualitative Data. Abingdon: Routledge; 1994. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bierman AS, Johns A, Hyndman B, et al. Social determinants of health and populations at risk. In: Bierman AS, editor. Project for an Ontario Women’s Health Evidenced-Based Report: Volume 2. Toronto: The POWER Study, Keenan Research Centre in the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agnew V. Racialized migrant women in Canada: essays on health, violence and equity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2009. [accessed 2017 July 1]. Available https://utorontopress.com/ca/racialized-migrant-women-in-canada-4. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, et al. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual) PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement Sci. 2018;13(Suppl 1):2. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0688-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schünemann H, Brozek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Version 3.2. GRADE Working Group; updated 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Couch J. On their own: perceptions of services by homeless young refugees. Developing Practice: The Child, Youth and Family Work Journal. 2012;31:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kissoon P. An uncertain home: refugee protection, illegal immigration status, and their effects on migrants’ housing stability in Vancouver and Toronto. Canadian Issues. 2010. [accessed 2017 Sept 1]. pp. 64–7. Available: https://search.proquest.com/openview/6b1915ffff359e7e96dc30b86274b798/1?pqorigsite=gscholar&cbl=43874.

- 37.Im H. A social ecology of stress and coping among homeless refugee families [dissertation] Minneapolis (MN): University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy; 2011. [accessed 2017 Sept 1]. Available https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/116170. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dwyer P, Brown D. Accommodating ‘others’?: Housing dispersed, forced migrants in the UK. J Soc Welf Fam Law. 2008;30:203–18. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Couch J. “My life just went zig zag”: Refugee young people and homelessness”. Youth Stud Aust. 2011;30:22–32. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Couch J. ‘Neither here nor there’: refugee young people and homelessness in Australia. Children and Youth Services Review. 2017;74:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 41.St Arnault D, Merali N. Pathways for refugees’ descent into homelessness in Edmonton, Alberta: the urgent need for policy and procedural change. J Int Migr Integr. 2019;20:1161–79. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mostowska M. Homelessness abroad: “place utility” in the narratives of the Polish homeless in Brussels. Int Migr. 2014;52:118–29. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mostowska M. Migration and Homelessness: The Social Networks of Homeless Poles in Oslo. J Ethn Migr Stud. 2013;39:1125–40. [Google Scholar]

- 44.d’Addario S, Hiebert D, Sherrell K. Restricted access: the role of social capital in mitigating absolute homelessness among immigrants and refugees in the GVRD. Refuge Canada’s Journal on Refugees. 2007;24:107–15. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paradis E, Novac S, Sarty M, et al. Better off in a shelter? A year of homelessness housing among status immigrant, non-status migrant, Canadian-born families. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness; 2009. [accessed 2017 Sept 1]. Available: www.homelesshub.ca/resource/42-better-shelter-year-homelessness-housing-among-status-immigrant-non-status-migrant. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sjollema SD, Hordyk S, Walsh CA, et al. Found poetry: finding home — A qualitative study of homeless immigrant women. J Poetry Ther. 2012;25:205–17. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walsh CA, Hanley J, Ives N, et al. Exploring the experiences of newcomer women with insecure housing in Montréal Canada. J Int Migr Integr. 2016;17:887–904. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Polillo A, Sylvestre J. An exploratory study of the pathways into homelessness among of foreign-born and Canadian-born families: a timeline mapping approach. Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness. 2019 Dec 19; doi: 10.1080/10530789.2019.1705518.. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Polillo A, Kerman N, Sylvestre J, et al. The health of foreign-born homeless families living in the family shelter system. Int J Migr Health Soc Care. 2018;14:260–8. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hanley J, Ives N, Lenet J, et al. Migrant women’s health and housing insecurity: an intersectional analysis. Int J Migr Health Soc Care. 2019;15:90–106. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ravnbøl CI. Doubling syndemics: ethnographic accounts of the health situation of homeless Romanian Roma in Copenhagen. Health Hum Rights. 2017;19:73–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dans AL, Dans LF, Agoritsas T, et al. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: A Manual for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2008. Applying results to individual patients; pp. 273–89. [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Neill J, Tabish H, Welch V, et al. Applying an equity lens to interventions: using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mostowska M. ‘We shouldn’t but we do …’: framing the strategies for helping homeless EU migrants in Copenhagen and Dublin. Br J Soc Work. 2014;44(Suppl 1):i18–34. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pottie K, Batista R, Mayhew M, et al. Improving delivery of primary care for vulnerable migrants: Delphi consensus to prioritize innovative practice strategies. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:e32–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saad A, Pottie K, Chiu CP. WHO Guidance on Research Methods for Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management. Geneva: World Health Organization; Refugees and internally displaced populations. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suleman S, Garber KD, Rutkow L. Xenophobia as a determinant of health: an integrative review. J Public Health Policy. 2018;39:407–23. doi: 10.1057/s41271-018-0140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Modood T, Berthoud R, Lakey J, et al. PSI report 843. London (UK): Policy Studies Institute; 1997. Ethnic minorities in Britain: diversity and disadvantage. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nazroo JY, Bhui KS, Rhodes J. Where next for understanding race/ethnic inequalities in severe mental illness? Structural, interpersonal and institutional racism. Sociol Health Illn. 2020;42:262–76. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.13001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Farmer PE, Nizeye B, Stulac S, et al. Structural violence and clinical medicine. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Larchanché S. Intangible obstacles: health implications of stigmatization, structural violence, and fear among undocumented immigrants in France. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:858–63. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Konczal L, Varga L. Structural violence and compassionate compatriots: immigrant health care in South Florida. Ethn Racial Stud. 2012;35:88–103. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Magwood O, Leki VY, Kpade V, et al. Common trust and personal safety issues: a systematic review on the acceptability of health and social interventions for persons with lived experience of homelessness. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0226306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Purkey E, Patel R, Phillips SP. Trauma-informed care: better care for everyone. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:170–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Steel Z, Chey T, Silove D, et al. Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302:537–49. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fenta H, Hyman I, Noh S. Mental health service utilization by Ethiopian immigrants and refugees in Toronto. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:925–34. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000249109.71776.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Whitley R, Kirmayer LJ, Groleau D. Understanding immigrants’ reluctance to use mental health services: a qualitative study from Montreal. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51:205–9. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shannon P, Im H, Becher E, et al. Screening for war trauma, torture, and mental health symptoms among newly arrived refugees: a national survey of U.S. refugee health coordinators. J Immigr Refug Stud. 2012;10:380–94. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shannon PJ, Wieling E, Simmelink-McCleary J, et al. Beyond Stigma: Barriers to Discussing Mental Health in Refugee Populations. J Loss Trauma. 2015;20:281–96. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sijbrandij M, Acarturk C, Bird M, et al. Strengthening mental health care systems for Syrian refugees in Europe and the Middle East: integrating scalable psychological interventions in eight countries. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(Suppl 2):1388102. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1388102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pottie K, Kendall CE, Aubry T, et al. Clinical guideline for homeless and vulnerably housed people, and people with lived homelessness experience. CMAJ. 2020;192:E240–54. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.190777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Legido-Quigley H, Pocock N, Tan ST, et al. Healthcare is not universal if undocumented migrants are excluded. BMJ. 2019;366:l4160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Malena C, Forster R, Singh J. Social Development Papers: Participation and Civic Engagement Paper No. 76. Washington (DC): Social Development, The World Bank; 2004. [accessed 2020 Apr. 1]. An introduction to the concept and emerging practice. Available http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/327691468779445304/pdf/310420PAPER0So1ity0SDP0Civic0no1076.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 74.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]