Abstract

Most shoulder injuries occur due to repetitive overhead movements. Before studying the treatment of these shoulder injuries, it is paramount that health professionals have an understanding of the etiology of and the underlying mechanisms for shoulder pathologies. The act of overhead throwing is an eloquent full-body motion that requires tremendous coordination from the time of force generation to the end of the pitch. The shoulder is a crucial component of the upper-body kinetic chain, as it transmits force created in the lower body to the arm and hand to provide velocity and accuracy to the pitch.

Keywords: shoulder, joint instability, athletic injuries

Introduction

Pitchers tend to have shoulder injuries as a result of the high forces to which this joint is submitted during the pitch. The dynamic stabilizers of the glenohumeral joint include the rotator cuff, the scapulothoracic muscles and the long head of the biceps tendon. The static stabilizers static include the bone anatomy, the fibrocartilaginous lip, and the joint capsule. A single traumatic event can cause an injury; however, it is more common that the repetitive overload leads to failure of one or more structures. The act of pitching requires a coordinate action that progresses from the tip of the toes to the fingers of the hand. This string of events was described conceptually as kinetic chain. 1 In order for this to work effectively, a sequential muscular activity is necessary so that the energy generated in the lower part of the body is transmitted to the upper part and, lastly, to the ball. 2 The speed of the ball is determined by the efficiency of this process. Body rotation and the position of the scapula are key elements in the kinematic chain. In professional pitchers, there is a delicate balance between mobility of the shoulder and stability. The shoulder needs to be mobile enough so that the extreme points of the rotation are achieved and the speed is transmitted to the ball; however, at the same time, the shoulder must stay stable so that the humeral head stays within the glenoidal cavity, creating a stable hub for rotation, which is known as “thrower's paradox.” 3 At each pitch, the soft tissue envelope that circles the shoulder is submitted to a load that is very close to the maximum load supported, which leads to the possibility of injury. 3 Even though the standards of the injuries in cases of pitcher shoulder are common and predictable, there still is controversy about the exact mechanisms that lead to these injuries. Recent biomechanical studies have helped improve the understanding of the pathogenesis of the injuries in pitchers. 4 5 6 Moreover, quantitative information about the normal or pathological biomechanics and kinematics have helped the development of strategies for the prevention and treatment of injuries, as well as for rehabilitation. 7 8 9

Pitch Kinematics

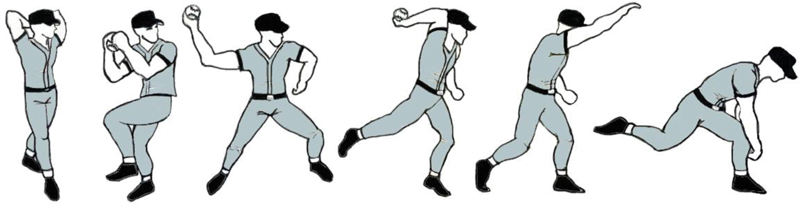

The pitch was divided into six phases, which usually take less than two seconds to occur. 10 11 The first 3 phases consist of preparation, stride and arm elevation, and take approximately 1.5 seconds in total. Although the fourth phase, acceleration, lasts about 0.05 seconds, the highest angular speeds and the greatest change in rotation occur during this phase. 12 The last two phases are deceleration and execution, and, together, they last approximately 0.35 seconds 12 ( Figure 1 ). As certain lesions occur at certain stages, it is important to determine when pain or a problem occur.

Fig. 1.

Phases of the pitch: (1) preparation; (2) stride; (3) arm elevation; (4) acceleration; (5) deceleration; and (6) execution/finish. Source: Drawing by the author.

The speed of the ball depends on a variety of biomechanical factors, but is more directly related to the amount of lateral rotation that the shoulder performs. 13 To generate maximum pitch speed in the most efficient way, the lower and upper extremities must work in a synchronized and coordinated way. Professional pitchers can generate ball speeds that exceed 144.8 km/h; to create such a speed, the shoulder reaches angular speeds of up to 7 thousand degrees/s. 13 After the release of the ball, the shoulder of a professional pitcher can be exposed to distracting forces of up to 950 N. 14 In the deceleration phase, there are compression forces created by the rotator cuff and deltoid muscles in the 1,090 N range, as well as posterior shear forces of up to 400 N. 14 The anterior part of the capsule resists approximately 800 N to 1200 N in individuals aged 20 to 30 years. 15 Therefore, if compressive forces do not counterbalance the high forces of distraction, injuries will occur. 15 The study by Kibler et al 1 largely contributed to the understanding of scapular dynamics, injury prevention and treatment. It is estimated that only half of the kinetic energy transmitted to the ball comes from the arm and shoulder. The other half is generated by the rotation of the trunk and lower limbs, and is transferred to the upper extremity through the scapular joint, making this joint an important, but often neglected, part of the kinetic chain. 16 A dynamic analysis of the shoulders during the pitch added to our current knowledge of normal and abnormal function and, by demonstrating which muscle groups are active during the pitch in each phase, it helped guide the development of prevention and rehabilitation programs. 17

Pathogenesis of Lesions

The pitcher's shoulder is susceptible to injury due to the convergence of the following factors: attenuation of the constrictors of the anterior capsule, contracture of the posterior capsule, development of scapular dyskinesia, kinetic chain breakage and repetitive contact of the greater tuberosity and the posterosuperior lip. Each of these factors was evaluated and strategies were suggested for injury prevention.

Previous Capsule Laxity

Biomechanical studies have shown that the anterior capsule, particularly the anterior band of the lower glenohumeral ligament, is the main restrictor of the anterior humerus translation with the arm in abduction and lateral rotation. 18 19 20 Therefore, repetitive stress in this area and the pitcher's desire to reach increasing levels of lateral rotation lead to a laxity of the anterior capsule. 18 19 20 Although the assigned causes are controversial, pitchers in fact have more passive lateral rotation than rotation of the contralateral shoulder. 21 22 If the gain in lateral rotation is greater than the loss of medial rotation, there is laxity of the restrictors. 21 22 In support of this, a work by Jobe et al 23 describes the tensioning of the anterior capsule as a means for the athlete to resume pitching. Although in the study by Jobe et al 23 this procedure was successful for patients (68% of the patients presented excellent results and returned to their preinjury levels, and 96% were satisfied with the surgery), the violation of the subscapularis muscle and the excessive tension explain why not all patients were able to return to their pre-injury levels after the reconstruction. With the progression of the anterior laxity, there is increased lateral rotation and increased contact between the back of the cuff and the lip, which facilitates the occurrence of injuries. 24

Subsequent Capsule Contracture

Over time, pitchers develop decreased medial rotation, especially when measured during abduction. 25 It is believed that this decrease in medial rotation occurs for two reasons. First, the increase in the retroversion of the humerus observed in pitchers manifests itself with a loss of medial rotation. However, this loss, due to bone remodeling, is accompanied by a symmetrical gain in lateral rotation. 25 Another means of medial-rotation loss is the contracture of the posterior capsule. It is believed that the median-rotation deficit of the glenohumeral joint occurs as a scar process in response to chronic distracting forces applied to the posterior capsule during the performance of the pitch. 25 Rotational loss due to capsular contracture is evident when the median-rotation deficit of the glenohumeral joint exceeds the one that can be explained only by bone remodeling (more than 12°), and when the loss of medial rotation exceeds the increase in lateral rotation compared to the contralateral side. 25

Biomechanical Consequences of the Medial Rotation Deficit of the Glenohumeral Joint

Current clinical and biomechanical studies 26 27 have shown that the median-rotation deficit of the glenohumeral joint may be the sentinel event in the pathological cascade that many pitchers go through. The authors found that pitchers who had superior labial lesions had a median rotation deficit of the glenohumeral joint greater than 25°. 26 27 Even small degrees of medial-rotation deficit of the glenohumeral joint (such as 5°, for example) put the shoulder at risk of injury and eventual need for surgery. 26 27 The posterosuperior displacement that occurs with the median rotation deficit of the glenohumeral joint is due to posterior and lower capsular contracture, which does not enable the total lateral rotation of the humerus. Therefore, the athlete begins to rotate around a new center of rotation, which is more posterior and proximal. Essentially, a contracted posteroinferior capsule displaces the humerus more posteriorly and proximally ( Figure 2 ). 6

Fig. 2.

Posterior and proximal displacement of the humeral head. Source: Drawing by the author.

Scapular Dyskinesia

Dyskinesia is a static or dynamic abnormality of the scapular position. Shoulder pain leads to an inhibition of the lower trapezius and anterior serratus muscles, and to a contracture of the upper trapezius and smaller pectoral muscles. 28 29 30 31 This muscle imbalance leads to a prostration of the scapula. Pitchers with loss of medial rotation due to capsular contracture end up using medial scapular rotation to perform the pitch. Over time, the scapula loses the static restrictors, and probably overloads the dynamic restrictors, and the scapula deviates from the midline and moves anteriorly. 32 Thomas et al 33 demonstrated that the greater the median rotation deficit, the greater the changes in the position and mobility of the scapula. They evaluated 43 professional baseball players, and, in 22 athletes, deficits greater than 15° were found, in which there was higher scapular dyskinesia, with statistical significance. In another study by Thomas et al, 34 a temporal relationship was demonstrated between scapular dyskinesia and the medial-rotation deficit of the glenohumeral joint, in which more experienced baseball players had greater deficits, with statistical significance.

Effects of Excessive Scapular Protraction

There are several biomechanical consequences of a scapula with excessive medial protraction or rotation. First, there is a weakness of the rotator cuff. As the rotator cuff complex essentially originates from the scapula, if there is an unstable platform, these muscles will not function properly. 35 In addition, increased protraction increases the version of the scapula, leading to anterior destabilization and increased overload in the anterior ligaments. 36 Excessive protraction also increases the degree of impact between the posterior rotator cuff and the posterior region of the glenoid during abduction and lateral rotation. 26 The study by Laudner et al 37 evaluated that pitchers diagnosed with pathological internal impact showed a statistical significant increase in the elevation of the sternoclavicular joint and scapular deviation during shoulder elevation in the plane of the scapula.

Common Pathological Conditions and Treatment Options

Mobility and Instability

Mobility is defined as passive movement of a joint in a special direction or rotation. 38 39 Hyperelasticity can be physiological or pathological, and may predispose to lesions. The term shoulder instability is reserved for the feeling of excessive humeral head movement in relation to the glenoid, which is usually associated with pain or discomfort. Few pitchers have symptoms of instability, although the term instability has been used in many studies to describe the syndrome that occurs in pitchers. While some degree of hyperelasticity can help the athlete compete at a high level in sports involving pitching, the excess may be responsible for the development of certain pathological conditions of the shoulder. This has been called atraumatic instability, which is believed to be due to the repetitive stress that occurs during pitches. 40 Kuhn et al 41 coined the term pathological hyperelasticity, which we also believe is a more accurate description of what is actually happening.

SLAP Injuries

The superior labral tear from anterior to posterior (SLAP) lesion is an important clinical cause of shoulder pain. Burkhart and Morgan 42 proposed that SLAP injuries in pitchers occur by the peel-back mechanism, which is defined as an increase in tension at the origin of the biceps during maximum lateral rotation during the pitch. Laboratory studies have shown that the long head of the biceps is an important dynamic restrictor of lateral rotation when the arm is abducted. 43 Conservative treatment is recommended initially, and its main objectives are to provide a decrease in pain, a gain in motion arc and a focus on dynamic strengthening, with an emphasis on the stabilizers of the scapula and rotator cuff. 42 If this fails, the surgical treatment is indicated, which usually is arthroscopic and varies according to the degree of the injury. 42

Rotator-Cuff Injuries

About 62% of the injuries to the pitcher's rotator cuff are partial-joint injuries. 6 These injuries in pitchers are usually found posterosuperiorly at the junction of the adrenal and infraspinal insertions. 44 45 Physiotherapy should be considered the initial treatment for partial cuff injuries in pitchers. Simple debridement has not shown good results in pitchers. The study by Payne et al 46 evaluated athletes submitted to simple debridement who were divided into two groups (pitchers with traumatic injuries and non-traumatic injuries). In patients with traumatic injuries, there was a satisfactory result in 86% of the cases, and 64% returned to the sport. In the pitchers with non-traumatic injuries, there were satisfactory results in 66% of the cases, and return to the sport in 45% of the cases.

Impact

Different types of impact have been described in the literature, including the classic, subacromial, secondary and internal impacts. 47 48 49 50 51 52 The internal impact is a pathological phenomenon in which the rotator cuff meets the posterosuperior aspect of the lip with the shoulder at the maximum degree of abduction and lateral rotation. 53 54 Several studies have shown that this type of impact is most likely caused by fatigue of the scapular waist muscles due to lack of conditioning or overtraining. 55 56 These studies have shown that, during acceleration phase of the pitch, the humerus must be aligned with the scapular plane. From the moment the muscles become fatigued, the humerus comes out of the plane of the scapula, which is called hyperangulation, leading to an overload of the anterior capsule. 57

General Treatment Guidelines

The treatment begins with conservative measures. The contracture of the posterior capsule should be addressed, and a stretching and mobilization program must be carried out. The stretching should isolate the glenohumeral joint so that scapular compensation is minimized. 26 The evaluation of the kinetic chain is essential. Lumbar contracture, weakness of the hip abductors and decreased medial-leg rotation should be investigated. 26 Scapular dyskinesia, which is commonly present, can usually be treated with exercises that help restore normal scapular mobility. The first step in scapular rehabilitation should focus on neuromuscular reeducation of the escaping stabilizing muscles. Strengthening should be initiated after this phase. 26 Strengthening the muscles of the rotator cuff should be performed, especially of the infraspinatus muscle, through lateral rotation exercises with resistance, which protects the rotator cuff from injury. 26

The surgical treatment is indicated in cases of failure of the conservative treatment. Three to four months of physiotherapy are usually attempted, and the therapy should be prolonged if the athlete presents progressive improvement of the condition. 26 Most pitchers, especially younger ones, are able to recover from the moment there is resolution of the scapular dyskinesia and the medial-rotation deficit.

Final Considerations

The performance of pitchers is often limited by shoulder injuries. These problems are complex and, therefore, difficult to manage. The problems occur as a result of a combination of muscle imbalance, muscle fatigue, hyperlaxity of the anterior capsule, contracture of the posterior capsule, altered mechanics of the pitch, scapular dyskinesia, increased humeral retroversion, and repetitive microtraumas. As a result, in pitchers we have observed lesions involving the lip, the joint side of the back of the rotator cuff, and the proximal insertion of the long head of the biceps.

The mechanisms and etiologies of the injuries in pitchers are becoming more well-defined. Although there is controversy over what would be the initial event, the typical injury patterns remain the same.

Before we think about treatment options, it is essential to get a detailed history, and to perform a physical examination and additional imaging studies to get to the correct diagnosis. The treatment of shoulder injuries should be initiated with a protocol that focuses on restoring the arc of motion, strengthening and specific stretching to promote stability of the scapula, shoulder and core muscles (deep muscles of the abdominal, lumbar and pelvic regions that aim to maintain the stability of this region). In addition, physicians, physiotherapists and trainers involved with pitchers should have extensive understanding of the entire pathophysiological cascade that leads to injuries in these athletes.

Conflito de Interesses Os autores declaram não haver conflito de interesses.

Trabalho desenvolvido no Grupo de Ombro e Cotovelo, Centro de Traumatologia do Esporte, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil.

Work developed in the Shoulder and Elbow Group, Centro de Traumatologia do Esporte, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Referências

- 1.Kibler W B. The role of the scapula in athletic shoulder function. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(02):325–337. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260022801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirashima M, Kadota H, Sakurai S, Kudo K, Ohtsuki T. Sequential muscle activity and its functional role in the upper extremity and trunk during overarm throwing. J Sports Sci. 2002;20(04):301–310. doi: 10.1080/026404102753576071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilk K E, Meister K, Andrews J R. Current concepts in the rehabilitation of the overhead throwing athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(01):136–151. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300011201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werner S L, Guido J A, Jr, Stewart G W, McNeice R P, VanDyke T, Jones D G. Relationships between throwing mechanics and shoulder distraction in collegiate baseball pitchers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(01):37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakshi N, Freehill M T. The Overhead Athletes Shoulder. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2018;26(03):88–94. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burkhart S S, Morgan C D, Kibler W B. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology Part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(04):404–420. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mlynarek R A, Lee S, Bedi A. Shoulder Injuries in the Overhead Throwing Athlete. Hand Clin. 2017;33(01):19–34. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn J E. Throwing, the Shoulder, and Human Evolution. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(03):110–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaremski J L, Wasser J G, Vincent H K. Mechanisms and Treatments for Shoulder Injuries in Overhead Throwing Athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2017;16(03):179–188. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meister K. Injuries to the shoulder in the throwing athlete. Part one: Biomechanics/pathophysiology/classification of injury. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(02):265–275. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280022301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin D J, Wong T T, Kazam J K. Shoulder Injuries in the Overhead-Throwing Athlete: Epidemiology, Mechanisms of Injury, and Imaging Findings. Radiology. 2018;286(02):370–387. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017170481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pappas A M, Zawacki R M, Sullivan T J. Biomechanics of baseball pitching. A preliminary report. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(04):216–222. doi: 10.1177/036354658501300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dillman C J, Fleisig G S, Andrews J R. Biomechanics of pitching with emphasis upon shoulder kinematics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18(02):402–408. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1993.18.2.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhn J E, Lindholm S R, Huston L J.Failure of the biceps-superior labral complex (SLAP lesion) in the throwing athlete: a biomechanical model comparing maximal cocking to early deceleration[abstract]J Shoulder Elbow Surg 20009463 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reeves B. Experiments on the tensile strength of the anterior capsular structures of the shoulder in man. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1968;50(04):858–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chu S K, Jayabalan P, Kibler W B, Press J.The Kinetic Chain Revisited: New Concepts on Throwing Mechanics and Injury PM R 20168(3, Suppl)S69–S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.David G, Magarey M E, Jones M A, Dvir Z, Türker K S, Sharpe M. EMG and strength correlates of selected shoulder muscles during rotations of the glenohumeral joint. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2000;15(02):95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(99)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Connell P W, Nuber G W, Mileski R A, Lautenschlager E. The contribution of the glenohumeral ligaments to anterior stability of the shoulder joint. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(06):579–584. doi: 10.1177/036354659001800604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Brien S J, Schwartz R S, Warren R F, Torzilli P A. Capsular restraints to anterior-posterior motion of the abducted shoulder: a biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4(04):298–308. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(05)80024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMahon P J, Tibone J E, Cawley P W. The anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament: biomechanical properties from tensile testing in the position of apprehension. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(05):467–471. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(98)90196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bigliani L U, Codd T P, Connor P M, Levine W N, Littlefield M A, Hershon S J. Shoulder motion and laxity in the professional baseball player. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(05):609–613. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown L P, Niehues S L, Harrah A, Yavorsky P, Hirshman H P. Upper extremity range of motion and isokinetic strength of the internal and external shoulder rotators in major league baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(06):577–585. doi: 10.1177/036354658801600604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jobe F W, Giangarra C E, Kvitne R S, Glousman R E. Anterior capsulolabral reconstruction of the shoulder in athletes in overhand sports. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(05):428–434. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karduna A R, McClure P W, Michener L A, Sennett B. Dynamic measurements of three-dimensional scapular kinematics: a validation study. J Biomech Eng. 2001;123(02):184–190. doi: 10.1115/1.1351892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kay J, Kirsch J M, Bakshi N. Humeral Retroversion and Capsule Thickening in the Overhead Throwing Athlete: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(04):1308–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burkhart S S, Morgan C D, Kibler W B. Shoulder injuries in overhead athletes. The “dead arm” revisited. Clin Sports Med. 2000;19(01):125–158. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson J E, Fullmer J A, Nielsen C M, Johnson J K, Moorman C T., 3rd Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit and Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(05):2.325967118773322E15. doi: 10.1177/2325967118773322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kibler W B, McMullen J. Scapular dyskinesis and its relation to shoulder pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11(02):142–151. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200303000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pink M M, Perry J. St Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1996. Biomechanics of the shoulder. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McClure P W, Michener L A, Sennett B J, Karduna A R. Direct 3-dimensional measurement of scapular kinematics during dynamic movements in vivo. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(03):269–277. doi: 10.1067/mse.2001.112954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McQuade K J, Dawson J, Smidt G L. Scapulothoracic muscle fatigue associated with alterations in scapulohumeral rhythm kinematics during maximum resistive shoulder elevation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28(02):74–80. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pink M M. Understanding the linkage system of the upper extremity. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2001;9(01):52–60. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas S J, Swanik K A, Swanik C B, Kelly J D., 4th Internal rotation deficits affect scapular positioning in baseball players. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(06):1551–1557. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1124-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas S J, Swanik K A, Swanik C B, Kelly J D. Internal rotation and scapular position differences: a comparison of collegiate and high school baseball players. J Athl Train. 2010;45(01):44–50. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kibler W B, Sciascia A, Dome D. Evaluation of apparent and absolute supraspinatus strength in patients with shoulder injury using the scapular retraction test. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(10):1643–1647. doi: 10.1177/0363546506288728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiser W M, Lee T Q, McMaster W C, McMahon P J. Effects of simulated scapular protraction on anterior glenohumeral stability. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(06):801–805. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270061901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laudner K G, Myers J B, Pasquale M R, Bradley J P, Lephart S M. Scapular dysfunction in throwers with pathologic internal impingement. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36(07):485–494. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilk K E, Andrews J R, Arrigo C A, Keirns M A, Erber D J. The strength characteristics of internal and external rotator muscles in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21(01):61–66. doi: 10.1177/036354659302100111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryu R KN, Dunbar W H, V, Kuhn J E, McFarland E G, Chronopoulos E, Kim T K.Comprehensive evaluation and treatment of the shoulder in the throwing athlete Arthroscopy 200218(09, Suppl 2):70–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeFroda S F, Goyal D, Patel N, Gupta N, Mulcahey M K. Shoulder Instability in the Overhead Athlete. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2018;17(09):308–314. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuhn J E, Lindholm S R, Huston L J, Soslowsky L J, Blasier R B. Failure of the biceps superior labral complex: a cadaveric biomechanical investigation comparing the late cocking and early deceleration positions of throwing. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(04):373–379. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burkhart S S, Morgan C D. The peel-back mechanism: its role in producing and extending posterior type II SLAP lesions and its effect on SLAP repair rehabilitation. Arthroscopy. 1998;14(06):637–640. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(98)70065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuhn J E, Huston L J, Soslowsky L J, Shyr Y, Blasier R B.External rotation of the glenohumeral joint: ligament restraints and muscle effects in the neutral and abducted positions J Shoulder Elbow Surg 200514(1, Suppl S)39S–48S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walch G, Boileau P, Noel E, Donell S T. Impingement of the deep surface of the supraspinatus tendon on the posterosuperior glenoid rim: An arthroscopic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1(05):238–245. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miniaci A, Mascia A T, Salonen D C, Becker E J. Magnetic resonance imaging of the shoulder in asymptomatic professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(01):66–73. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300012501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Payne L Z, Altchek D W, Craig E V, Warren R F. Arthroscopic treatment of partial rotator cuff tears in young athletes. A preliminary report. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(03):299–305. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jobe F W, Kvitne R S, Giangarra C E. Shoulder pain in the overhand or throwing athlete. The relationship of anterior instability and rotator cuff impingement. Orthop Rev. 1989;18(09):963–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jobe F W, Jobe C M. Painful athletic injuries of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;(173):117–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warner J J, Micheli L J, Arslanian L E, Kennedy J, Kennedy R. Scapulothoracic motion in normal shoulders and shoulders with glenohumeral instability and impingement syndrome. A study using Moiré topographic analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(285):191–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morris A D, Kemp G J, Frostick S P. Shoulder electromyography in multidirectional instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(01):24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crockett H C, Gross L B, Wilk K E. Osseous adaptation and range of motion at the glenohumeral joint in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(01):20–26. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300011701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bach H G, Goldberg B A. Posterior capsular contracture of the shoulder. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(05):265–277. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200605000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jobe C M. Posterior superior glenoid impingement: expanded spectrum. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(05):530–536. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(95)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walch G, Liotard J P, Boileau P, Noël E. [Postero-superior glenoid impingement. Another shoulder impingement] Rev Chir Orthop Repar Appar Mot. 1991;77(08):571–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jobe C M. Superior glenoid impingement. Orthop Clin North Am. 1997;28(02):137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(05)70274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paley K J, Jobe F W, Pink M M, Kvitne R S, ElAttrache N S. Arthroscopic findings in the overhand throwing athlete: evidence for posterior internal impingement of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(01):35–40. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(00)90125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jobe C M, Pink M M, Jobe F W, Shaffer B. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1996. Anterior shoulder instability, impingement, and rotator cuff tear: theories and concepts; pp. 164–176. [Google Scholar]