Abstract

Massive irreparable posterosuperior rotator-cuff tears are debilitating lesions that usually require surgical treatment. Even though there is no consensus regarding the best surgical technique, tendinous transfers around the shoulder are the most commonly performed procedures. The latissimus dorsi tendon remains the most commonly used, but different modifications to the original technique have been shown to minimize complications and to improve functional results and satisfaction. Other techniques, such as the transfer of the lower trapezius tendon, are promising and should be considered, especially for patients with isolated loss of external rotation. The present paper is a literary review regarding tendon transfers for irreparable posterosuperior rotator-cuff tears.

Keywords: shoulder, rotator cuff injuries, tendon transfers, review

Introduction

Rotator-cuff-tear (RCT) repairs are among the most common shoulder surgeries. 1 However, tendon-to-bone healing is not always successful or predictable, 2 because it depends on a variety of factors, including biomechanical and biological ones, the latter being influenced by the patient's age. 3 As the population is rapidly aging, the prevalence of failed rotator-cuff repairs is also increasing. 1 3 The failure rates of massive posterosuperior rotator-cuff repairs are reported to range from 21% to as high as 91%. 4 5 6 Failures and complications following revisions are reported to be even significantly higher. 7 8

There is no consensus regarding the definition of irreparable RCTs. That being said, whenever a lesion is determined to be irreparable, there are many treatment options, starting with nonsurgical treatments. 9 Regarding the surgical options, there is controversy about the best treatment available. Boileau el al 10 and Walch et al 11 showed satisfactory results after tenotomy of the long head of the biceps (LHB) alone in elderly patients. Other procedures have been reported, including rotator-cuff debridement (with or without concomitant suprascapular nerve release), 12 partial cuff repair, 13 14 15 tendon transfers, 16 17 18 19 and reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA). 20 The latter, however, is probably not the best option in younger and physically-active patients, because the longevity of these implants in this population is yet unknown, and also because RSAs can still be used as a salvage procedure after the failure of other techniques. More recently, superior shoulder capsular reconstruction 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 has been advocated, but its reported functional results are in their infancy, 23 29 and longer follow-up periods are needed to confirm its long-term efficacy. 30

Despite being relatively difficult surgical procedures and requiring accurate patient selection, tendon transfers can significantly improve the quality of life of the patients. 16 18 31 This is especially important for young and physically-active patients with lesions graded as Hamada et al 32 stages 1 and 2 (that is, without both glenohumeral arthritis and static proximal humeral head migration), because they may be the only feasible definitive (that is, long-term) treatments available. 30

The aim of the present paper is to review the literature regarding tendon transfers for irreparable posterosuperior RCTs (that is, the ones involving the supra- and infraspinatus tendons), as the posterosuperior is by far the most common type of RCT. 1 In this context, the latissimus dorsi tendon (LDT) –accompanied or not by the teres major tendon (TMT) – is the most commonly transferred tendon. 33 The alternatives include isolated TMT transfer 34 35 36 37 and the more recently described transfer of the lower trapezius tendon (LTT). 38 39

Latissimus-Dorsi-Tendon (LDT) Transfer

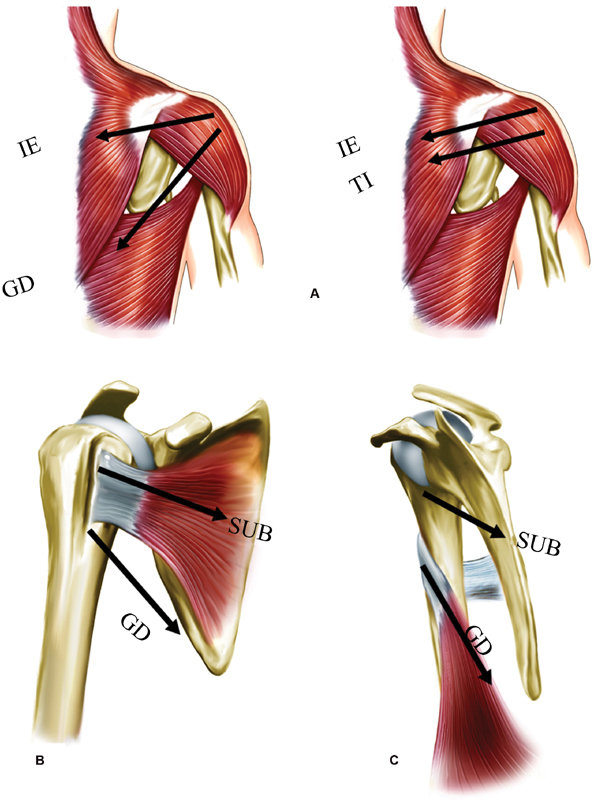

The earliest and also most studied transfer is that of the LDT, which was originally described by Gerber et al, 17 and is performed using a double open-approach technique (a posterior approach and a superior transdeltoid approach). The transferred tendon is attached superolaterally to the greater tuberosity (by transosseous sutures) and anteriorly to the subscapularis tendon, therefore changing the latissimus dorsi into a shoulder abductor and external rotator (as opposed to its original role as an internal rotator an adductor) ( Figure 1 ). The rationale behind this procedure is: to restore humeral-head centering (as the intact anterior subscapularis force is now joined by the new posterior force 40 ); and to improve active external rotation (ER) of the shoulder.

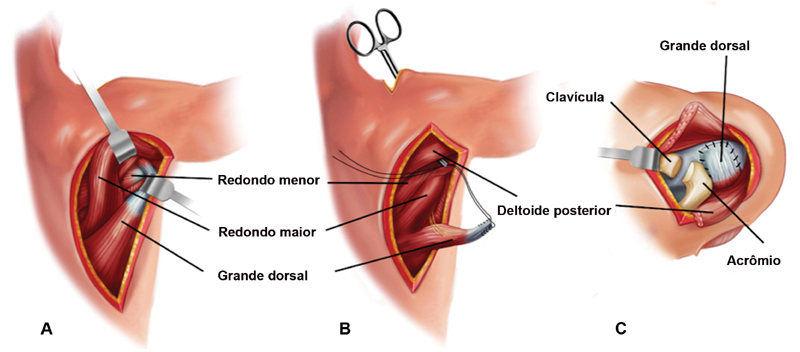

Fig. 1.

( A-C ) Latissimus dorsi transfer using a double-incision technique. Representation of a right shoulder. ( A ) Posterior view. A posterior incision is made over the lateral border of the palpable latissimus dorsi belly, which is then separated from the more superior and medial teres major muscle. ( B ) Posterior view. The tendon is detached from the humerus and then is transported to the subacromial space with a clamp that is brought from the superior to the posterior incision, placed between the posterior deltoid and the long head of the triceps muscle. ( C ) Superior view. The transferred tendon is then anchored to an osseous trough in the superolateral humeral head (over-the-top placement), and any remaining cuff is sutured to the transfer.

In 1992, Gerber 16 published his postoperative results. A total of 17 patients were followed for an average of 33 months postoperatively, showing that for the subgroup of patients with normal subscapularis function (12 of the total 17), around 80% of normal shoulder function was reestablished. Therefore, this was the first study indicating that the LDT could be a safe and valuable alternative for these patients.

Many other subsequent papers 18 19 31 33 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 have also shown that satisfactory results following LDT transfer could be achieved. However, these satisfactory results could not be easily predicted. The probable reason for that, besides the proper surgical technique, is that proper patient selection may also crucial in order to obtain satisfactory and predictable results, as it will be discussed subsequently.

While no upper age limit has been defined, a recent systematic review 46 noted a mean age of 59 years for LDT transfer, and showed that the indication could be even extended to elderly patients with Hamada et al 32 stage-3 arthropathies.

Preoperative integrity from both the deltoid and the subscapularis have been shown 19 44 45 49 to be really important in order to achieve good outcomes, as forward elevation and shoulder stability respectively drastically decrease with their insufficiency. 16 42 50 51 52 However, we should notice that patients with concomitant subscapularis lesions limited only to its proximal insertion (but without subscapular dysfunction – that is negative lift-off sign) have been successfully treated since Gerber's initial publication. 16 18 47 51

Another likely predictor of worse postoperative outcomes and decreased active ER is preoperative atrophy and fatty infiltration (Goutallier 3 or higher) of the teres minor muscle. 47 52 53 Despite that, Moursy et al 52 noticed that even though patients with these findings fared worse overall, they were the ones with greater gain in postoperative ER; they concluded that this happened because preoperative degeneration of the teres minor muscle in all of their cases correlated with lesser preoperative active ER. 52

Good preoperative shoulder movement is also essential, specifically passive forward flexion (FF) greater than 80°. 41 Furthermore, pseudoparetic shoulders (defined as active FF lower than 90° 54 ) and previous surgical procedures have also been demonstrated to correlate with poorer outcomes. 18 55 56

Different techniques for LDT transfer were also developed. Habermeyer et al 43 described a single-posterior-incision approach with a more posterior attachment site into the humeral head. Hertzberg et al 57 reported a similar technique, but instead, with a correction on the original site of insertion of the infraspinatus. However, the authors pointed that occasional proximal subscapularis lesions cannot be adequately treated through this approach. Nonetheless, Habermeyer et al 43 showed clinical results comparable to those of Gerber's two-incision method, with mean Constant-Murley scores improving from 46.5 points (29.3 to 66.7) preoperatively to 74.6 points (64.5 to 81.5) postoperatively.

Recently, there have been reports of arthroscopically-assisted transfers of this tendon. 31 48 58 59 Grimberg and Kany 31 reported outcomes equivalent to those of historical open approaches, and this one-incision arthroscopically-assisted approach provided better mechanical resistance to traction due to the tubularized tendon fixation using two suture threads, resulting in a total of four suture ends for fixation. 60

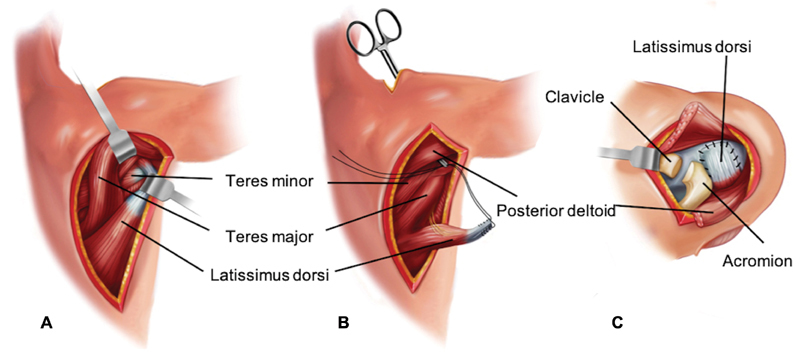

In 2019, Miyazaki et al 61 described a new technique for open LDT transfer. The authors claimed that the original technique has two main drawbacks that could predispose to complications and unsatisfactory functional results: 1) postoperative rupture of the origin of the deltoid, as its detachment from the acromion is necessary during the superior approach; and 2) postoperative rupture of the transfer. In an attempt to avoid these problems, they developed the following modifications. Through a deltopectoral approach, the LDT is detached from the humerus shaft, and is then reinforced and elongated with a tendinous allograft (calcaneus or quadricipital grafts), and finally transferred around the humerus and fixed to the superolateral aspect of the greater tuberosity. ( Fig. 4 ) Nonetheless, no clinical results have been published so far.

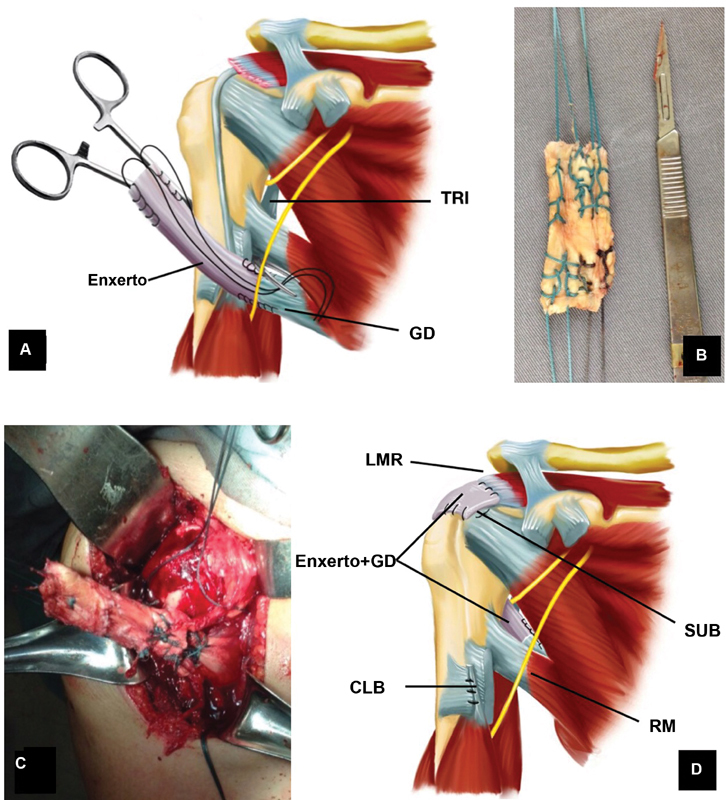

Fig. 4.

( A-D ) Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer elongated and reinforced with a tendinous allograft and performed through an isolated deltopectoral approach, as described by Miyazaki et al. 61 ( A ) Figure depicting tendon preparation before transfer. ( B ) Allograft preparation. ( C ) After passing the transfer behind the humerus. ( D ) Figure depicting final configuration of the latissimus dorsi tendon. Abbreviations: AG, allograft; TRI, triceps, LD, latissimus dorsi; RCT, rotator-Cuff Tear; LHB, long head of the biceps; TM, teres major; sub, subscapularis.

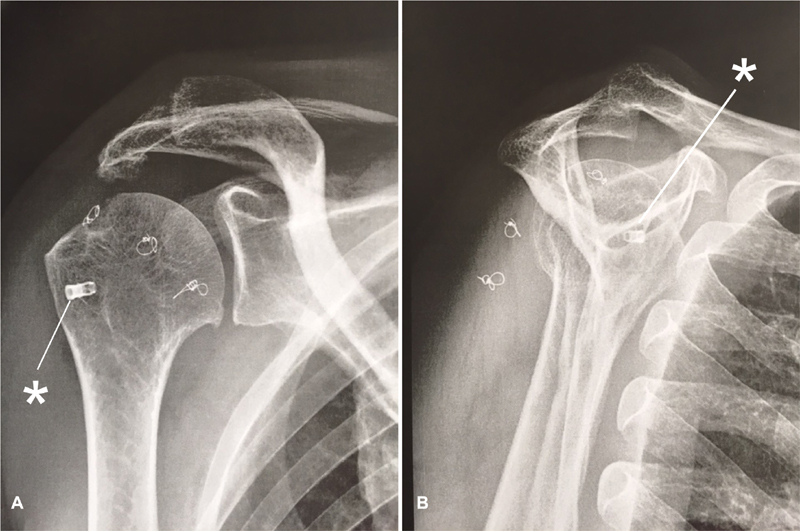

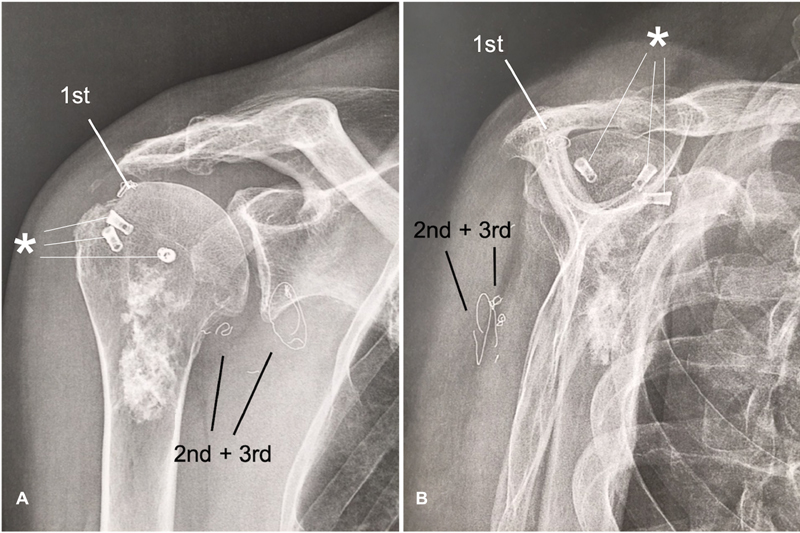

We agree with the findings of Moursy et al 52 that it is difficult to assess the integrity of the transfer through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Regarding this matter, Kany et al 62 published in 2018 an interesting and insightful study. They evaluated 60 patients (after losing 6 patients to follow-up), with a mean postoperative follow-up of 35.2 months. The surgical technique in all of the patients involved placing three metallic markers distanced 2 cm, 4 cm and 6 cm from the tip of the tendon, therefore enabling an easy diagnosis of transfer ruptures with simple X-rays ( Figure 2 ). The results showed 23 (38.6%) ruptures ( Figure 3 ), which in itself was a major factor for worse postoperative functional results and satisfaction using 7 different functional and satisfaction scores ( p < 0.05 in all of them).

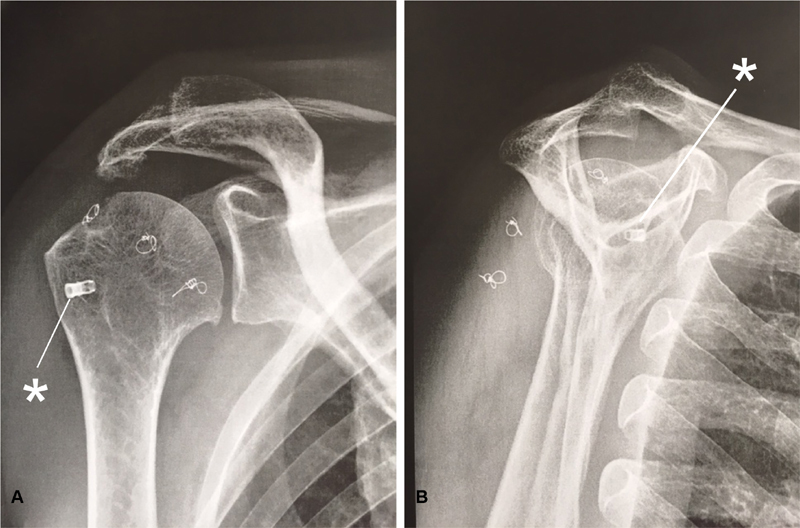

Fig. 2.

( A, B ) Postoperative radiographs after a latissimus dorsi transfer with 3 metal markers (placed at 2 cm, 4 cm and 6 cm from the tip of the tendon). The asterisks indicate the metallic anchor from a previous (failed) rotator-cuff repair. ( A ) Anteroposterior view. ( B ) Scapular profile view.

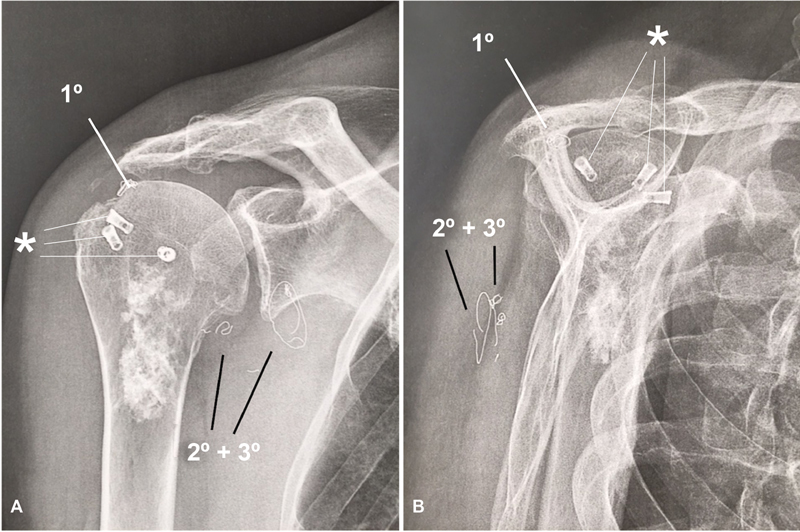

Fig. 3.

( A, B ) Postoperative rupture of a latissimus dorsi tendon transfer. Note the increased distance between the intact first marker (1st) and the displaced second and third (2nd and 3rd) metal markers. The asterisks indicate metallic anchors from a previous (failed) rotator-cuff repair. Note that the calcified lesion in the proximal part of the humerus is an enchondroma, not at all related to the procedure or the rotator-cuff tear. ( A ) Anteroposterior view. ( B ) Scapular profile view.

Checchia et al 30 have hypothesized that the outcomes of LDT transfers would be determined not only by patient selection or concomitant subscapularis insufficiency, as mentioned by Gerber 16 and other authors, 19 44 45 but also by respecting five specific principles of tendon transfers:

Accurate positioning of the transferred tendon;

Physiological tensioning of the transferred muscle-tendon unit;

Strong bone fixation of the reimplanted tendon;

Minimally-invasive surgery to reduce muscle scarring (without hindering the excursion of the transfer);

A synergistic transfer.

The ideal fixation site probably varies according to the preoperative clinical presentation. According to Walch et al, 63 the clinical presentation of these patients is variable, especially regarding the drop sign (also known as Hornblower sign), which indicates deficiency of the external rotators. Painful, pseudoparetic shoulders with negative drop signs (described by Boileau et al 64 as a ‘painful loss of active elevation’), should be treated, according to Gerber et al, 17 with an over-the-top transfer. This means the tendon should be transferred above the joint's center of rotation in order to act mainly as a humeral-head depressor. For patients with isolated positive drop signs (described by Boileau et al 64 as ‘isolated loss of external rotation’), the aim should be the fixation lateral to the joint's center of rotation. 43 57

The second principle is to control the muscle-belly tension. One can reason that insufficient tension would lead to a non-effective transfer. Alternatively, excessive tension could damage the transferred muscle-tendon unit. It has been proposed 30 that, in order to obtain appropriate tension, before releasing the latissimus dorsi from its original attachment, one should place two landmarks on the muscle while the shoulder is in maximum abduction and ER (which is the position of maximal physiological tension of the latissimus dorsi). At the time of tendon reattachment, the muscle should be retensioned to match the prerelease distance between these two markers.

-

The third principle regards the mechanical resistance of tendon-to-bone fixation. Since the metaphyseal bone is fragile, a resistant fixation method should be used. 65 For open approaches, it is believed that transosseous sutures are strong enough, especially if augmented with some sort of cortical reinforcement, as suggested in an article by Gerber et al. 66

Arthroscopic techniques, however, require implants to achieve proper tendon-to-bone attachment. Diop et al 67 published a cadaveric biomechanical study that compared a standard anchor-fixation method (in a simple double-row manner) to a technique of fixation of the tubularized LDT to the greater tuberosity with an interference screw. They have shown that the latter presents higher biomechanical performance – in terms of stiffness, cyclic displacements and load to failure – despite resulting in more complications (especially greater tuberosity fracture during bone drilling). 67 For this reason, some authors 68 prefer fixation of the tubularized tendon with a cortical button positioned onto the bicipital groove, thereby avoiding drilling through the greater tuberosity.

Another technique that improves tendon-to-bone healing involves removing cortical bony chips along with the LDT (by performing a delicate superficial osteotomy of the humeral cortex rather than a simple tenotomy). In fact, Moursy et al 52 have shown that this modification statistically results in fewer postoperative ruptures and better functional outcomes. Another possible alternative, as previously mentioned, is tendon reinforcement with the use of a tendinous allograft, as proposed by Miyazaki et al 61 ( Fig. 4 ).

The fourth principle aims to limit the surgical trauma to the tissues. As far as we are aware, this is not supported by any empirical data, except for the findings by Warner and Parsons 56 of suboptimal results regarding revisions or multiple simultaneous tendon transfers. However, we can reason that less trauma may improve healing because it minimizes iatrogenic devascularization, and it may also enable greater tendon excursion, as less scarring of the surrounding soft tissues is generated. Furthermore, minimally-invasive techniques, as arthroscopic approaches, preserve the deltoid muscle belly, which is especially important to shoulder function in the setting of a rotator-cuff deficiency. Even though it has been shown that every step of the LDT transfer can be performed exclusively through an arthroscopic approach (Lafosse, Nice Shoulder Course, 2016, unpublished data), we believe that this should be avoided, once our experience has shown that failing to release the latissimus dorsi attachment to the apex of the scapula (which in our opinion cannot be performed arthroscopically) results in postoperative scapular winging.

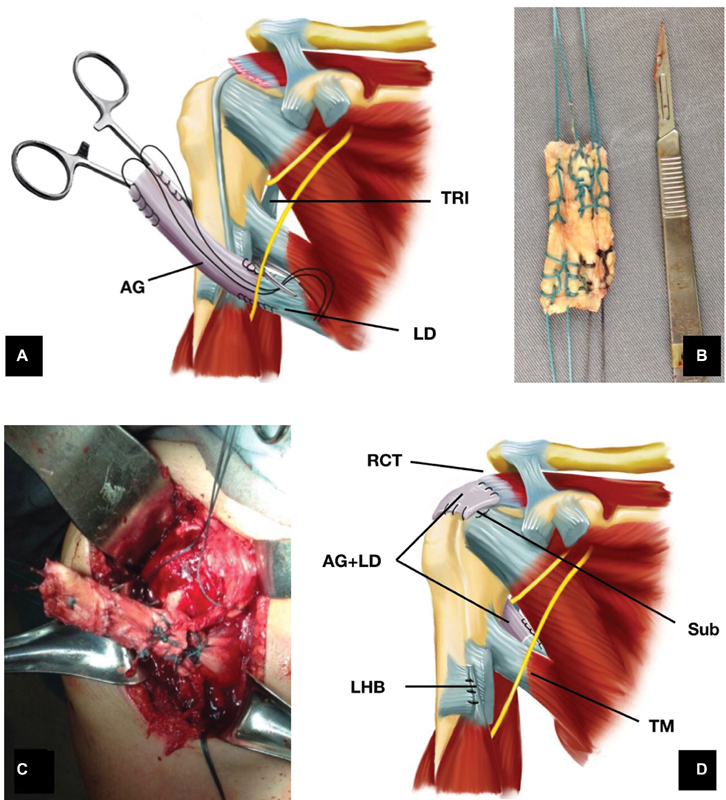

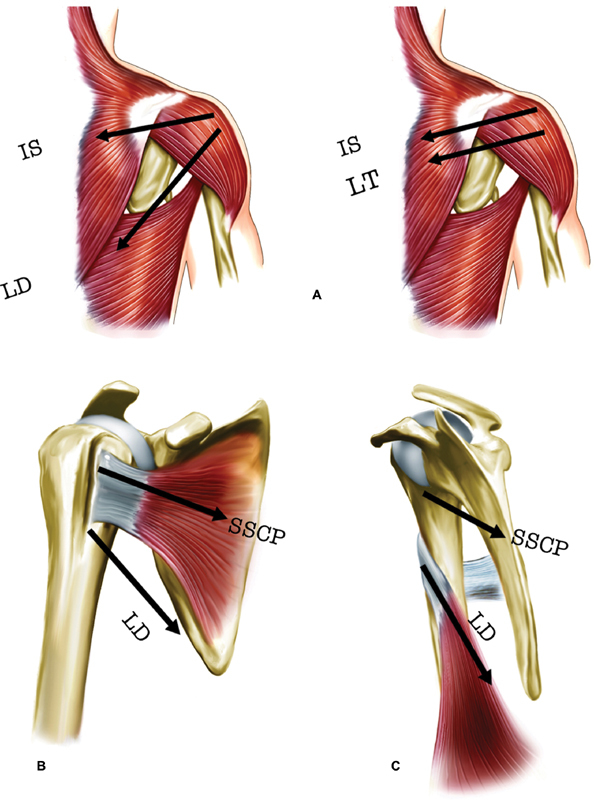

It can also be argued that the LDT transfer does not respect the fifth principle of tendon transfer, because this muscle is not originally an agonist of both FF and ER, and its line of action is more inferior and more posterior than that of the original cuff tendons ( Figure 5 ). Perhaps this is the main reason for the reported controversial and imperfect electromyographic results, 43 47 69 as well as for some of the reported unsatisfactory clinical results. 18 70

Fig. 5.

( A-C ) Drawings of the right shoulder. The line of pull from the lower trapezius (LT) more closely replicates the one from the infraspinatus (IS) than the one generated by the latissimus dorsi (LD). The line of pull from the LD closely replicates the line of pull from the subscapularis (SSCP). ( A ) Posterior view. ( B ) Anterior view. ( C ) Medial view.

Teres-Major-Tendon (TMT) Transfer

There are very few published studies regarding isolated TMT transfers for irreparable RCTs. All of them were performed in patients with isolated infraspinatus deficiency. The first series was reported in 1998 by Celli et al, 35 who achieved patient satisfaction and satisfactory functional results for all of their 6 patients. More recently, Celli et al, 34 published the long-term results of 20 patients with maintenance of the improved postoperative Constant-Murley scores. 34

More recently, Henseler et al 36 published short-term results of TMT transfers. At two years of follow-up, the patients had significant ( p < 0.05) improvements in ER, FF, and visual analogue scale and Constant-Murley scores. With a medium-term follow-up (mean of six years), Mansat et al 37 evaluated the results of 12 TMTs, showing results similar to those of Henseler et al. 36 Interestingly, the authors 37 could identify negative preoperative prognostic factors that included previous surgery and RCTs involving the subscapularis, as well as two positive prognostic factors: isolated involvement of the infraspinatus and of the functional teres minor. Furthermore, Mansat et al 37 described the following recommendations for TMT transfer: the patients should be under the age of 55 years, should have proper understanding of the lesion and the treatment, and should have intact subscapularis and anterior supraspinatus cable.

Lower-Trapezius-Tendon (LTT) Transfer

The double incision (a technique of prolonged LTT transfer with a tendinous autograft or allograft) has been recently investigated as an alternative to the LDT transfer for irreparable posterior RCTs and for chronic isolated musculotendinous tears of the infraspinatus. 33 38 39 71 Besides probably being technically easier than the LDT transfer, the line of pull of the lower-trapezius-muscle fibers more closely replicates those of the infraspinatus ( Figure 5 ). Furthermore, it has been shown that tension and excursion forces of the trapezius are very similar to those of the infraspinatus. 38 39

In a cadaveric study, Omid et al 39 concluded that the LTT transfer was biomechanically superior to the LDT transfer, providing greater ER forces. Hartzler et al 38 also found improved ER with the arm at the side compared to LDT transfer, but the LDT transfer was better at restoring the FF as well as the ER at 90° of abduction. More recently, in 2019, Reddy et al, 72 showed through a three-dimensional (3D) biomechanical virtual study (performing virtual LDT and LTT transfers in a computer software), that the LTT provided better abduction and ER moment arms when transferred to the infraspinatus insertion. However, LDT performed better when transferred to the supraspinatus insertion. Overall, the LTT transfer showed a biomechanical advantage compared with the LDT transfer because of stronger abduction moment arms.

In 2016, Elhassan et al, 71 were the first to report the outcomes following this technique. They evaluated 33 patients (26 men, with an average of 53 years of age; range: 31to 66 years) at an average follow-up of 47 months (range: 24 to 73 months). Except for one patient, who had a bone mass index of 36 kg/m 2 , all achieved statistically significant improvements in pain, subjective shoulder value, and disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) score, as well as statistically significant improvements to all active shoulder motions. Their results were, therefore, the first to show that this mode of treatment may be a good alternative, at least at early and medium follow-up.

In 2016, Elhassan et al 73 described a modification to their original technique in which, instead of creating a second lateral open approach, they would instead fix the transfer to the greater tuberosity under arthroscopic visualization. Nonetheless, they haven't published the results following this modification. However, in 2018, Valenti and Werthel 74 published the results following almost the same technique as the one published by Elhassan et al, 73 the only difference being the use of a semitendinosus tendon autograft instead of an Achilles allograft. They evaluated 14 patients after a mean follow-up of 24 months (range 12 to 36 months). Their results have shown gain in external rotation with the arm at the side of 24° and, in 90° of abduction, of 40°. The lag sign and the Hornblower sign have disappeared from every patient in whom they were present preoperatively. The Constant-Murley score improved from 35 (preoperatively) to 60 points (postoperatively), the SST, from 3.5 to 7.5, the SSV, from 30 to 60%, and the pain decreased from 7 to 2 (visual analogue scale). There were two cases of hematomas, and one was revised because of infection.

We are unaware of any other published study showing the results of lower trapezius transfer for irreparable RCTs. Despite all that, to date there are no clinical studies that suggest the superiority of latissimus dorsi transfer or lower trapezius transfer over the other.

Conclusion

Irreparable posterosuperior RCTs can be debilitating, and failed cuff repairs are still challenging conditions to treat. Different techniques have been developed, and the proposed benefits of tendon transfers are pain relief and some increased range of motion with potential increase to shoulder strength. The LDT remains the most commonly used method, and different modifications to the original technique have been shown to minimize complications and to improve functional results and satisfaction. Nonetheless, LTT transfers are promising and should be considered, especially for patients with isolated loss of external rotation. Its results, however, are limited to two series of cases, both of which have reported only short to midterm follow-up.

Conflito de Interesses Os autores declaram não haver conflito de interesses.

Trabalho realizado no Departamento de Ortopedia e Traumatologia da Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Santa Casa de São Paulo, Pavilhão “Fernandinho Simonsen”. Diretor: professor doutor Ivan Chakkour – São Paulo (SP), Brasil.

Work developed at the Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Santa Casa de São Paulo, Pavilhão “Fernandinho Simonsen”. Director: professor doctor Ivan Chakkour – São Paulo (SP), Brazil.

Referências

- 1.Tashjian R Z. Epidemiology, natural history, and indications for treatment of rotator cuff tears. Clin Sports Med. 2012;31(04):589–604. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galatz L M, Ball C M, Teefey S A, Middleton W D, Yamaguchi K. The outcome and repair integrity of completely arthroscopically repaired large and massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(02):219–224. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200402000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longo U G, Berton A, Papapietro N, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Epidemiology, genetics and biological factors of rotator cuff tears. Med Sport Sci. 2012;57:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000328868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartl C, Kouloumentas P, Holzapfel K. Long-term outcome and structural integrity following open repair of massive rotator cuff tears. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2012;6(01):1–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.94304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jo C H, Shin J S, Lee Y G. Platelet-rich plasma for arthroscopic repair of large to massive rotator cuff tears: a randomized, single-blind, parallel-group trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2240–2248. doi: 10.1177/0363546513497925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim S J, Kim S H, Lee S K, Seo J W, Chun Y M. Arthroscopic repair of massive contracted rotator cuff tears: aggressive release with anterior and posterior interval slides do not improve cuff healing and integrity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(16):1482–1488. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shamsudin A, Lam P H, Peters K, Rubenis I, Hackett L, Murrell G A. Revision versus primary arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a 2-year analysis of outcomes in 360 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(03):557–564. doi: 10.1177/0363546514560729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parnes N, DeFranco M, Wells J H, Higgins L D, Warner J J. Complications after arthroscopic revision rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(09):1479–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bokor D J, Hawkins R J, Huckell G H, Angelo R L, Schickendantz M S. Results of nonoperative management of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(294):103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boileau P, Baqué F, Valerio L, Ahrens P, Chuinard C, Trojani C. Isolated arthroscopic biceps tenotomy or tenodesis improves symptoms in patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(04):747–757. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walch G, Edwards T B, Boulahia A, Nové-Josserand L, Neyton L, Szabo I. Arthroscopic tenotomy of the long head of the biceps in the treatment of rotator cuff tears: clinical and radiographic results of 307 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(03):238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gartsman G M. Massive, irreparable tears of the rotator cuff. Results of operative debridement and subacromial decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(05):715–721. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim S J, Lee I S, Kim S H, Lee W Y, Chun Y M. Arthroscopic partial repair of irreparable large to massive rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(06):761–768. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iagulli N D, Field L D, Hobgood E R, Ramsey J R, Savoie F H., 3rd. Comparison of partial versus complete arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(05):1022–1026. doi: 10.1177/0363546512438763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berth A, Neumann W, Awiszus F, Pap G. Massive rotator cuff tears: functional outcome after debridement or arthroscopic partial repair. J Orthop Traumatol. 2010;11(01):13–20. doi: 10.1007/s10195-010-0084-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerber C. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable tears of the rotator cuff. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(275):152–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerber C, Vinh T S, Hertel R, Hess C W. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff. A preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(232):51–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iannotti J P, Hennigan S, Herzog R. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Factors affecting outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(02):342–348. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warner J J. Management of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: the role of tendon transfer. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:63–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulieri P, Dunning P, Klein S, Pupello D, Frankle M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tear without glenohumeral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(15):2544–2556. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mihata T, Watanabe C, Fukunishi K, Ohue M, Tsujimura T, Kinoshita M. Arthroscopic Superior Capsular Reconstruction Restores Shoulder Stability and Function in Patients with Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears: A Prospective Study (SS-15) Arthroscopy. 2011;27(05):e36–e37. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mihata T, McGarry M H, Pirolo J M, Kinoshita M, Lee T Q. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248–2255. doi: 10.1177/0363546512456195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mihata T, Lee T Q, Watanabe C. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(03):459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gracitelli M E, Beraldo R A, Malavolta E A, Assunção J H, de Oliveira D R, Ferreira Neto A A. Reconstrução da cápsula superior com aloenxerto de fáscia lata para roturas irreparáveis do tendão do músculo supraespinhal. Rev Bras Ortop. 2019;54(05):591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.rbo.2017.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burkhart S S, Denard P J, Adams C R, Brady P C, Hartzler R U. Arthroscopic Superior Capsular Reconstruction for Massive Irreparable Rotator Cuff Repair. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5(06):e1407–e1418. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartzler R U, Burkhart S S. Superior Capsular Reconstruction. Orthopedics. 2017;40(05):271–280. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20170920-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirahara A M, Adams C R. Arthroscopic Superior Capsular Reconstruction for Treatment of Massive Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears. Arthrosc Tech. 2015;4(06):e637–e641. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tokish J M, Beicker C. Superior Capsule Reconstruction Technique Using an Acellular Dermal Allograft. Arthrosc Tech. 2015;4(06):e833–e839. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Denard P J, Brady P C, Adams C R, Tokish J M, Burkhart S S. Preliminary Results of Arthroscopic Superior Capsule Reconstruction with Dermal Allograft. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(01):93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.08.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Checchia C, Domos P, Grimberg J, Kany J. Current Options in Tendon Transfers for Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears. JBJS Rev. 2019;7(02):e6. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.18.00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grimberg J, Kany J. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable postero-superior cuff tears: current concepts, indications, and recent advances. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2014;7(01):22–32. doi: 10.1007/s12178-013-9196-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamada K, Fukuda H, Mikasa M, Kobayashi Y. Roentgenographic findings in massive rotator cuff tears. A long-term observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(254):92–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Omid R, Lee B. Tendon transfers for irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(08):492–501. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-08-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Celli A, Marongiu M C, Rovesta C, Celli L. Transplant of the teres major in the treatment of irreparable injuries of the rotator cuff (long-term analysis of results) Chir Organi Mov. 2005;90(02):121–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Celli L, Rovesta C, Marongiu M C, Manzieri S. Transplantation of teres major muscle for infraspinatus muscle in irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(05):485–490. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(98)90199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henseler J F, Nagels J, van der Zwaal P, Nelissen R GHH. Teres major tendon transfer for patients with massive irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears: Short-term clinical results. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(04):523–529. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B4.30390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mansat P, Dotziz A, Bellumore Y, Mansat M.Teres major flap: surgical anatomy, technique of harvesting, methods of fixation, postoperative management Springer; Paris: 2011[cited 2017 Sep 23]. p. 49–64. (Collection GECO). Available from:https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-2-8178-0049-3_5 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartzler R U, Barlow J D, An KN, Elhassan B T. Biomechanical effectiveness of different types of tendon transfers to the shoulder for external rotation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(10):1370–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Omid R, Heckmann N, Wang L, McGarry M H, Vangsness C T, Jr, Lee T Q. Biomechanical comparison between the trapezius transfer and latissimus transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(10):1635–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burkhart S S, Athanasiou K A, Wirth M A. Margin convergence: a method of reducing strain in massive rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1996;12(03):335–338. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(96)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buchmann S, Plath J E, Imhoff A B. [Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator tears: indication, surgical technique, and modifications] Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2012;24(06):502–512. doi: 10.1007/s00064-012-0162-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Azab H M, Rott O, Irlenbusch U. Long-term follow-up after latissimus dorsi transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(06):462–469. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Habermeyer P, Magosch P, Rudolph T, Lichtenberg S, Liem D. Transfer of the tendon of latissimus dorsi for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff: a new single-incision technique. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(02):208–212. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B2.16830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Irlenbusch U, Bracht M, Gansen H K, Lorenz U, Thiel J. Latissimus dorsi transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears: a longitudinal study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(04):527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miniaci A, MacLeod M. Transfer of the latissimus dorsi muscle after failed repair of a massive tear of the rotator cuff. A two to five-year review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(08):1120–1127. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199908000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Namdari S, Voleti P, Baldwin K, Glaser D, Huffman G R. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(10):891–898. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nové-Josserand L, Costa P, Liotard J P, Safar J F, Walch G, Zilber S. Results of latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable cuff tears. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(02):108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Villacis D, Merriman J, Wong K, Rick Hatch G F., III Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears: a modified technique using arthroscopy. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2(01):e27–e30. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Irlenbusch U, Bensdorf M, Gansen H K, Lorenz U. [Latissimus dorsi transfer in case of irreparable rotator cuff tear--a comparative analysis of primary and failed rotator cuff surgery, in dependence of deficiency grade and additional lesions] Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2003;141(06):650–656. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-812410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glanzmann M C, Goldhahn J, Flury M, Schwyzer H K, Simmen B R. Deltoid flap reconstruction for massive rotator cuff tears: mid- and long-term functional and structural results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(03):439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Werner C ML, Zingg P O, Lie D, Jacob H AC, Gerber C. The biomechanical role of the subscapularis in latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(06):736–742. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moursy M, Forstner R, Koller H, Resch H, Tauber M. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears: a modified technique to improve tendon transfer integrity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(08):1924–1931. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Costouros J G, Espinosa N, Schmid M R, Gerber C. Teres minor integrity predicts outcome of latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(06):727–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.02.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tokish J M, Alexander T C, Kissenberth M J, Hawkins R J. Pseudoparalysis: a systematic review of term definitions, treatment approaches, and outcomes of management techniques. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(06):e177–e187. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gerber C, Maquieira G, Espinosa N.Transfert du grand dorsal pour le traitement des ruptures massives de la coiffe des rotateurs : quels facteurs déterminent le résultat final? Rev Chir Orthop Repar Appar Mot 200490(05, Suppl 1):158–162. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Warner J J, Parsons I M., IV Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer: a comparative analysis of primary and salvage reconstruction of massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(06):514–521. doi: 10.1067/mse.2001.118629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herzberg G, Urien J P, Dimnet J. Potential excursion and relative tension of muscles in the shoulder girdle: relevance to tendon transfers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8(05):430–437. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(99)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Castricini R, Longo U G, De Benedetto M. Arthroscopic-Assisted Latissimus Dorsi Transfer for the Management of Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears: Short-Term Results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(14):e119. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grimberg J, Kany J, Valenti P, Amaravathi R, Ramalingam A T. Arthroscopic-assisted latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(04):599–6070. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sirveaux F, Favard L, Oudet D, Huquet D, Walch G, Molé D. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff. Results of a multicentre study of 80 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(03):388–395. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b3.14024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miyazaki A N, Checchia C S, Lopes W C, Fonseca Filho J M, do Val Sella G, Silva L A. Transferência tendínea do grande dorsal com enxerto tendíneo homólogo para as lesões irreparáveis do manguito rotador: técnica cirúrgica. Rev Bras Ortop. 2019;54(01):99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kany J, Grimberg J, Amaravathi R S, Sekaran P, Scorpie D, Werthel J D. Arthroscopically-Assisted Latissimus Dorsi Transfer for Irreparable Rotator Cuff Insufficiency: Modes of Failure and Clinical Correlation. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(04):1139–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walch G, Boulahia A, Calderone S, Robinson A H. The ‘dropping’ and ‘hornblower's’ signs in evaluation of rotator-cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(04):624–628. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b4.8651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boileau P, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Neyton L, Trojani C. Modified latissimus dorsi and teres major transfer through a single delto-pectoral approach for external rotation deficit of the shoulder: as an isolated procedure or with a reverse arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(06):671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.02.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clavert P, Bouchaïb J, Sommaire C, Flurin P H, Hardy P. Observe-t-on une modification de la densité osseuse du tubercule majeur après 70ans? Rev Chir Orthop Traumatol. 2014;100(01):94–96. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gerber C, Schneeberger A G, Beck M, Schlegel U. Mechanical strength of repairs of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(03):371–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Diop A, Maurel N, Chang V K, Kany J, Duranthon L D, Grimberg J. Tendon fixation in arthroscopic latissimus dorsi transfer for irreparable posterosuperior cuff tears: an in vitro biomechanical comparison of interference screw and suture anchors. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2011;26(09):904–909. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goldstein Y, Grimberg J, Valenti P, Chechik O, Drexler M, Kany J. Arthroscopic fixation with a minimally invasive axillary approach for latissimus dorsi transfer using an endobutton in massive and irreparable postero-superior cuff tears. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2013;7(02):79–82. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.114223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aoki M, Okamura K, Fukushima S, Takahashi T, Ogino T. Transfer of latissimus dorsi for irreparable rotator-cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(05):761–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gerber C, Maquieira G, Espinosa N. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(01):113–120. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Elhassan B T, Wagner E R, Werthel J D. Outcome of lower trapezius transfer to reconstruct massive irreparable posterior-superior rotator cuff tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(08):1346–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reddy A, Gulotta L V, Chen X. Biomechanics of lower trapezius and latissimus dorsi transfers in rotator cuff-deficient shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019;28(07):1257–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Elhassan B T, Alentorn-Geli E, Assenmacher A T, Wagner E R. Arthroscopic-Assisted Lower Trapezius Tendon Transfer for Massive Irreparable Posterior-Superior Rotator Cuff Tears: Surgical Technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5(05):e981–e988. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Valenti P, Werthel J D. Lower trapezius transfer with semitendinosus tendon augmentation: Indication, technique, results. Obere Extrem. 2018;13(04):261–268. doi: 10.1007/s11678-018-0495-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]