Abstract

More than half of the world’s populations are considered to be infected by Helicobacter pylori. It causes a chronic inflammation of the stomach, which is implicated in the pathogenesis of gastric ulcer and cancer. Silibinin, a polyphenolic flavonoid derived from milk thistle, has been known for its hepatoprotective effects, and recent studies have revealed its chemopreventive potential. In the present study, we examined the anti-inflammatory effects of silibinin in human gastric cancer MKN-1 cells and in the stomach of C57BL/6 mice infected by H. pylori. Pretreatment with silibinin attenuated the up-regulation of COX-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in H. pylori-infected MKN-1 cells and mouse stomach. In addition, the elevated translocation and DNA binding of NF-κB and STAT3 induced by H. pylori infection were inhibited by silibinin treatment. Moreover, H. pylori infection in combination with high salt diet resulted in dysplasia and hyperplasia in mouse stomach, and these pathological manifestations were substantially mitigated by silibinin administration. Taken together, these findings suggest that silibinin exerts anti-inflammatory effects against H. pylori infection through suppression of NF-κB and STAT3 and subsequently, expression of COX-2 and iNOS.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Silibinin, NF-κB, STAT3, Gastritis

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection represents the major cause of gastritis which can progress to gastric cancer [1]. H. pylori resist to acidic conditions by releasing urease, which can neutralize gastric acid and provide the bacteria with suitable environment in the host for survival [2]. In addition, H. pylori can attach to the mucosa of stomach, leading to continuous generation of reactive oxygen species and stimulation of inflammation signaling in the gastric mucosa [3-5]. NF-κB and STAT3 are two of the major transcription factors activated by pro-inflammatory stmuli [6,7]. NF-κB is one of the essential transcription factors that regulate transcription of COX-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) genes whose overexpression is implicated in inflammation-associated cancer [8]. COX-2 is an important enzyme responsible for prostaglandin production during inflammation. iNOS that is upregulated by proinflammatory stimuli is essential for host immunity. STAT3 is also known to be overexpressed during chronic inflammation [9,10].

For treating patients with H. pylori infection, combination of anti-bacterial drugs has been used in general. Thus, triple and quadruple therapies including metronidazole, tetracycline and other drugs are effective in more than 90 percent of patients. However, such antibiotic drug combination for the treatment of H. pylori infection may cause serious side effects, such as increased diarrhea and nausea, and the bacteria often develop a tolerance against drugs [11]. In this context, naturally occurring anti-inflammatory substances, especially those of plant origin, have promise for use in preventing H. pylori-induced gastritis and subsequent gastric carcinogenesis [12].

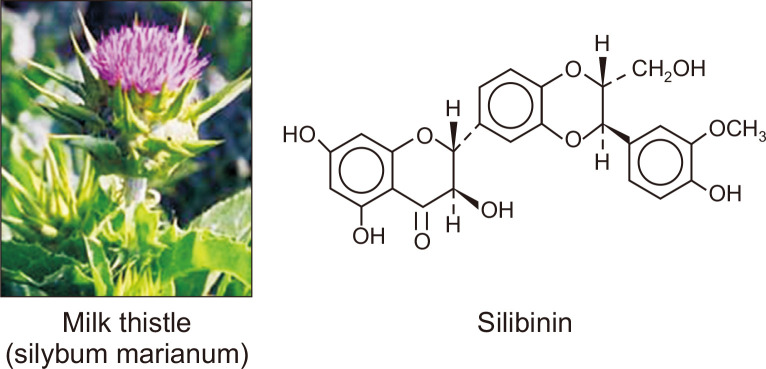

Silibinin is a major bioactive flavonolignan isolated from milk thistle seeds (Fig. 1) [13]. Generally, silymarin rather than silibinin has widely been known to have hepatoprotective properties [14]. Silymarin is a mixture of silidianin, silichristine, and silibinin [15]. Silibinin possesses strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects and has chemopreventive activities as well [16-18]. In the present study, we investigated the possible inhibitory effects of silibinin on inflammation caused by H. pylori infection in mouse stomach and in cultured human gastric epithelial cells. We also attempted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms with focus on NF-κB and STAT3 as potential targets.

Figure 1. The chemical structure of silibinin isolated from milk thistle seeds.

Adapted from the article of Singh and Agarwal (Clin Dermatol 2009;27:479-84) [13].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Silibinin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in sterile dimethyl sulfoxide and carboxymethycellulose (CMC) for treatment to cells and mice, respectively. RPMI 1640 medium and FBS were obtained from Giboco BRL (Grand Island, NY, USA). GasPak EZ, CO2 indicator, and tryptic soy were purchased from BD Bioscience (Franklin, NJ, USA). Rabbit polyclonal antibody was the product of NeoMarkers (Fremont, CA, USA). iNOS antibody for immunohistochemical analysis was supplied from BD Bioscience. Antibodies for Western blot analysis against iNOS, p65, p50 and α-tubulin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-STAT3 and Anti-P-STAT3 were obtained from Cell signaling Technology (Beverly, CA, USA). Mouse anti-lamin B was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The oligonuclotides containing the NF-κB and STAT3 binding consensus sequence are: NF-κB: 5′-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3′, STAT3: 5′-GAT CCT TCT GGG AAT TCC TAG ATC-3’ and the luciferase assay kit with reporter lysis buffer were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, USA).

Cell culture

Human gastric carcinoma (MKN-1) cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and a 100 ng/mL penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone mixture and maintained at 37°C under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air.

Helicobacter pylori culture

H. pylori (ATCC 43504) were provided in a frozen state by American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). H. pylori were cultured on tryptic soy agar (TSA) with 5% (v/v) sheep blood (BD Bioscience) and Listeria Primary Selective Enrichment supplement (SR0142E) (Hampshire, UK) at 37°C in a microaerophilic condition. The microaerophilic conditions were induced by CampyPack Plus (BD Bioscience) at 37°C under an atmosphere of 5% O2, 10% CO2, and 85% N2. H. pylori inoculated on the TSA were harvested into tryptic soy broth supplemented with 10% FBS in a microaerobic condition for next 2 days.

Inoculation of H. pylori

After pretreatment with silibinin for 1 hour, MKN-1 cells were infected with H. pylori (1 x 108 CFUs, 500 Multiple of infection [MOI]) for 7 hours.

Animal treatment

C57 black 6 (C57BL/6) female mice (5 weeks of age) were purchased from Orient Bio Inc. (Seongnam, Korea). H. pylori (100 µL, 1 x 108 CFUs/mouse) were inoculated to starved mice 5 times at 2 day intervals. Mice were given 7.5% high salt diet for 4 weeks, which was followed by administration of silibinin suspended in 0.5% CMC (20 mg/kg or 200 mg/kg) for 4 or 8 weeks.

H. pylori colonization and the CLO test

Half of the stomach tissues were placed in 1 mL of tryptic soy broth containing 10% FBS and homogenized with an UltraTurrax homogenizer. Ten-fold dilutions were made, and 100 µL aliquots of the dilutions were plated onto TSA. Colonies on the plate were counted, and bacterial counts were expressed as colony-forming units per gram of tissue. The color changing grade was determined by the Campylobacter-Like Organism (CLO) kit.

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNAs were isolated from MKN-1 cells using the TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen), and one microgram of total RNAs was reverse transcribed by M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega) following the protocol. One microliter of cDNA was subjected to PCR amplification: COX-2, iNOS and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The cDNA was analyzed in a PCR reaction (forward and reverse): iNOS, 5′-TGG TGC TGT ATT TCC TTA CGA GGC GAA GAA GG-3′ and 5′-GGT GCT ACT TGT TAG GAG GTC AAG TAA AGG GC-3′; COX-2, 5′- GCT GAG CCA TAC AGC AAA TCC-3′ and 5′- GGG AGT CGG GCA ATC ATC AG-3′; GAPDH, 5′AAG GTC GGA GTC AAC GGA TTT-3′ and 5′-GCA GTG AGG GTC TCT CTC CT-3′. These amplification products were analyzed on 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with SYBR Green (Invitrogen). The resulting fluorescence was detected by using ImageQuant LAS-4000 (GE healthcare, Seoul, Korea).

Measurement of immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was conducted to illustrate the nuclear translocation of NF-κB-p65 and STAT3. MKN-1 cells were placed on the eight-well chamber slide (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), pretreated with silibinin for 1 hour and infected by H. pylori for 7 hours. Cells were washed rapidly with filtered PBS and then fixed for 10 minutes at 4°C with 95% methanol/5% acetic acid. After washing the fixed cells with PBS, cells were permeabilized by 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. After rinse with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST), cells were treated for 1 hour at room temperature with blocking buffer composed of PBST containing 5% bovine serum albumin. Cells were incubated overnight with an antibody against p65 or STAT3 after 1:100 dilution with 1% bovine serum albumin at 4°C. The incubated cells were then rinsed with PBST, followed by labeling with diluted (1:1,000) Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody for additional 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were then rinsed with PBST and stained with propidium iodide (Invitrogen) or Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich Inc.) for 3 minutes in PBS. Stained cells were washed with PBS, analyzed under a confocal microscope and photographed.

Western blot analysis

MKN-1 cells placed in a 100 mm dish were pretreated with silibinin for 1 hour and then infected with H. pylori for 7 hours. After wash with cold PBS, the cells were digested at 4°C for 30 minutes in the lysis buffer (150 mmol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 25 mmol/L NaF, 20 mmol/L EGTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, and 1 mmole/L Na3VO4 with protease inhibitor cocktail tablet) (Cell signaling Technology) on ice followed by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 20 minutes. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and stored at –70°C until use. The protein was calculated by using the BSA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Protein samples were separated on an 8% to 15% SDS PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane at 300 mA for 3.5 hours. The blots were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) for 2 hours at room temperature and incubated overnight with primary antibodies in 3% non-fat dry milk in TBST at 4°C. After wash with TBST three times, blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies in 3% non-fat dry milk in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were rinsed three times again in TBST, and transferred protein were incubated with an enhanced chemiluminescence plus detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction and visualized with an X-ray film.

Transient transfection and NF-κB luciferase transfection

MKN-1 cells at a confluence of 60% to 70% were transfected with mock or NF-κB luc vector with lipofectamin 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the instructions supplied by the manufacturer. After 24 hours of transfection, cells were pretreated with silibilinin for 1 hour and infected with H. pylori for additional 7 hours. The cell lysis was carried out with the reporter lysis buffer (Promega). After the cell extract was mixed with a luciferase substrate, the luciferase activity was measured by the luminometer. The galactosidase assay was conducted according to manufacturer’s instructions with buffer (1 M MgCl2, 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 M NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4 [pH 7.5], o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside).

Nuclear protein extraction and electrophoresis mobility shift assay (EMSA)

After infected with H. pylori, cells were washed with cold PBS, centrifuged, and suspended in ice-cold isotonic buffer A (a plasma membrane lysis buffer containing 10 mmol/L 4-(2-hyfroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethane sulfonic acid [pH 7.9], 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L KCl, 0.5 mmol/L dithiothreitol and 0.2 mmol/L phenylmethane-sulfonyl fluoride). After incubation on ice for 10 minutes, 10% NP-40 was added and cells were gently inverted. Cells were centrifuged again and resuspended in ice-cold nuclear membrane lysis buffer containing 20 mmol/L 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethane sulfonic acid (pH 7.9), 20% glycerol, 420 mmol/L NaCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.2 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5 mmol/L dithiothreitol and 0.2 mmol/L phenylmethane-sulfonyl fluoride and incubated for 2 hours on ice with vortex mixing at 10 minutes intervals. The lysed nuclear fraction was centrifuged and the supernatant was collected and stored at –70°C. DNA binding activities of NF-κB and STAT3 were determined using the NF-κB oligonucleotide probe or STAT3 oligonucleotide probe each of which was labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by T4 polynuclotide kinase and purified on a Nick column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The binding reaction was performed in 25 µL of the mixture including 5 κL of incubation buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 1 mmole/L EDTA, 4% glycerol, and 0.1 µg/mL sonicated salmon sperm DNA), 10 µg of nuclear extracts, and [γ-32P]ATP-end labeled oligonucleotide. After 50 minutes incubation at room temperature, 2 L of 0.1% bromophenol blue was added, and samples were separated on a 7% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel at 150 V. Ultimately, the gel was dried, kept at –70°C for 2 to 4 days, and exposed to X-ray film.

Histopathological examinations

After treatment, all mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation. These tissue blots were fixed with 10% formalin before being embedded in paraffin. Each tissue blot section (4 µm) was stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Statistics analysis

When necessary, data were expressed as means ± SD, and statistical analysis was performed by using Gel-Pro analyzer program. Statistical significance of the obtained data was determined by conducting Student’s t-test and the P-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

H. pylori-induced expression of COX-2 and iNOS is attenuated by silibinin in MKN-1 cells

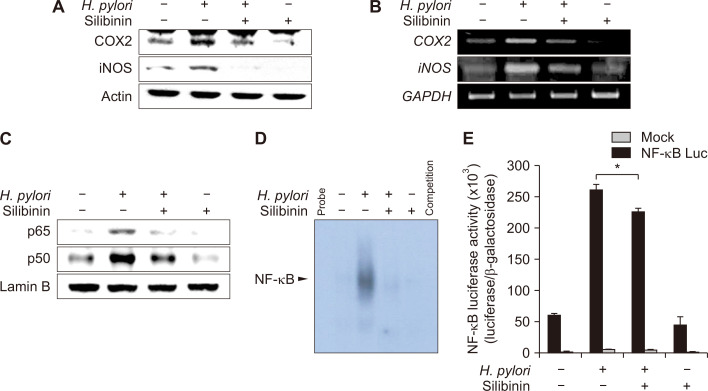

H. pylori infection is well known to induce gastritis, and up-regulation of inflammatory enzymes like COX-2 [19] and iNOS [20]. These enzymes play primary roles in mediating inflammation. In the present study, MKN-1 cells were pretreated with silibinin for 1 hour and subsequently infected by H. pylori (500 MOI). The H. pylori-induced expression of COX-2 and iNOS was decreased by silibinin in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). The mRNA levels of COX-2 and iNOS in H. pylori-infected cells were also reduced by pretreatment with silibinin (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. The effect of silibinin on Helicobacter pylori-induced expression of COX-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and NF-κB activation.

(A) Silibinin (100 µM) was treated for 1 hour to MKN-1 cells prior to infection with H. pylori (500 MOI) for 7 hours. Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies against COX-2 and iNOS. (B) Under the same conditions, total RNA was isolated and then analyzed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to measure the mRNA expression of COX-2 and iNOS. Actin and Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase levels were used as loading controls for immunoblot and RT-PCR analyses, respectively. (C) Cells were treated with silibinin for 1 hour prior to H. pylori (500 MOI) infection for 5 hours. The nuclear extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis to examine nuclear translocation. (D) The nuclear extracts from the infected cells were subjected to electrophoresis mobility shift assay to assess DNA binding of NF-κB as described in Materials and Methods. (E) Cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid construct harboring the NF-κB binging site or β-galactosidase control vector for 48 hours by using lipofectamin 2000 reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfected cells were pretreated with silibinin for 1 hour followed by H. pylori (500 MOI) infection for 5 hours and subsequently treated with reporter lysis buffer for measurement of luciferase activity. The luciferase activity was normalized with β-galactosidase activity. Columns, means (n = 3); bars, standard deviation; *significantly different between the numbers compared (P < 0.05).

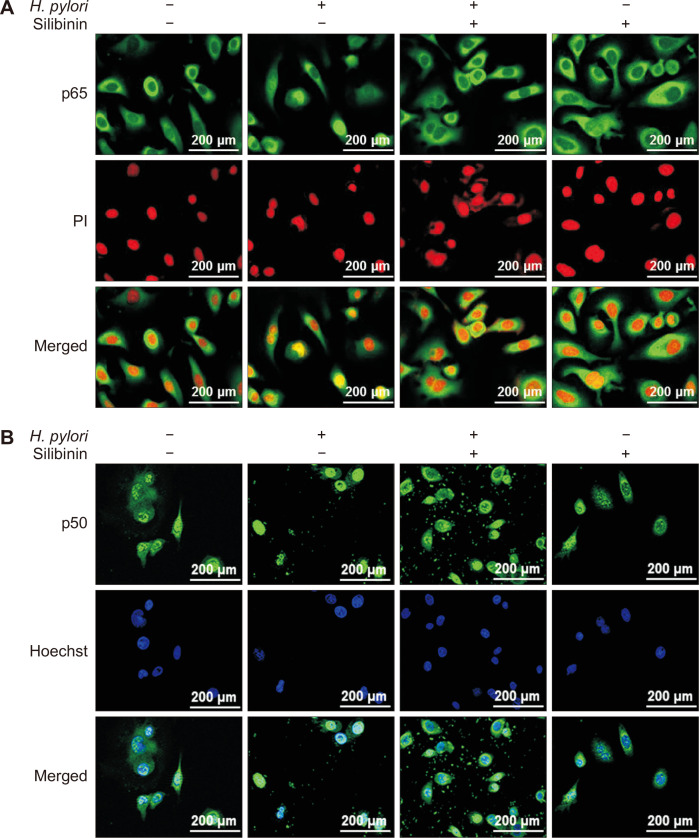

The broad diversity of genes regulated by NF-κB include cytokines (e.g., interleukin [IL]-6 and TNF-α), chemokines (e.g., IL-8 and RANTES), and inducible effector enzymes (e.g., iNOS and COX-2) [21]. We investigated whether silibinin could suppress the activation of transcriptional factors in nuclear extracts of MKN-1 cells stimulated with H. pylori. The nuclear translocation of NF-κB attenuated by H. pylori infection was inhibited by pretreatment with silibinin (Fig. 2C). The electrophoretic mobility shift assay revealed that silibinin suppressed H. pylori-induced NF-κB DNA binding (Fig. 2D). Consistent with enhanced DNA binding of NF-κB, its transcriptional activity was increased in H. pylori-infected cells, as determined by use of plasmid vector harboring the consensus NF-κB binding DNA oligonucleotides associated with a luciferase reporter gene. Silibinin attenuated NF-κB transcriptional activity induced by H. pylori (Fig. 2E). The most common functionally active NF-κB form consists of p65 and p50 subunits. The co-culture of MKN-1 cells with H. pylori induces nuclear localization of both subunits as demonstrated by immunocytochemical analysis, and this was abrogated by silibinin treatment (Fig. 3A and 3B). Bacterial lipopolysaccharide was used as a positive control for NF-κB activation.

Figure 3. The effects of silibinin nuclear localization of p65 and p50 subuits of NF-κB.

Immunostaining visualizes the location of p65 (A) or p50 (B) protein in the nucleus stained with propidium iodide (PI) or Hoechst. MKN-1 cells were treated with Helicobacter pylori in the presence or absence of silibinin as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with antibodies against p65 (A) and p50 (B) followed by treatment with 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG. Nuclei were visualized by PI (A) or Hoechst (B). Magnification: ×400.

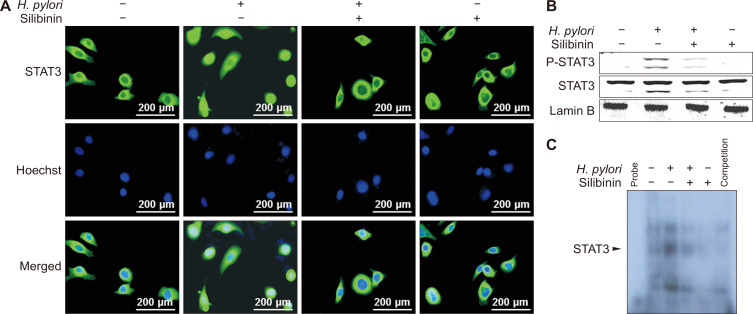

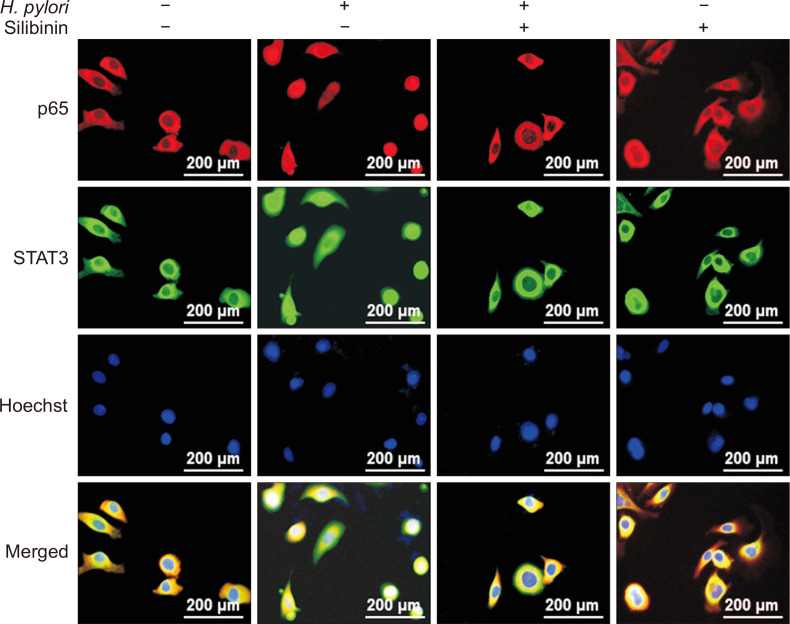

Besides NF-κB, STAT3 is recognized as a major mediator of inflammation associated with tumor promotion. STAT3 is activated through phosphorylation of tyrosine 705 by diverse protein tyrosine kinases [22,23]. As in the case of NF-κB, the nuclear accumulation of the phosphorylated STAT3 elevated by H. pylori was decreased by silibinin (Fig. 4A and 4B). We then conducted EMSA using STAT3 oligonucleotide as a probe and found that silibinin reduced H. pylori-induced STAT3 DNA binding (Fig. 4C). Notably, NF-κB and STAT3 co-localized in the nucleus of MKN-1 cells stimulated with H. pylori, which was blunted by silibinin (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. The effects of silibinin on Helicobacter pylori-induced STAT3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation and DNA binding of STAT3.

(A) Immunocytochemistry shows the location of STAT3 protein and Hoechst staining indicates the location of the nucleus. MKN-1 cells were treated with H. pylori in the presence or absence of silibinin as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with antibody against STAT3 followed by treatment with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG. Note that the STAT3 antibody used for immunocytochemustry cross-reacts with the phosphorylated form of STAT3 (P-STAT3). Nuclei were visualized by Hoechst 33258 (magnification: ×400). MKN-1 cells were treated with silibinin (100 µM) for 1 hour prior to H. pylori (500 MOI) infection for 5 hours (magnification: ×400). (B) MKN-1 cells were treated with silibinin (100 µM) for 1 hour prior to H. pylori (500 MOI) infection for 5 hours. The nuclear extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis to assess nuclear translocation of P-STAT3. (C) The infected nuclear extract cells were subjected to electrophoresis mobility shift assay to determine the nuclear translocation and DNA binging of STAT3.

Figure 5. The effects of silibinin on co-localization of NF-κB and STAT3 in the nucleus.

Immunostaining visualizes the location of p65 and STAT3 in the nucleus stained with Hoechst. MKN-1 cells were treated with Helicobacter pylori in the presence or absence of silibinin as described above (magnification: ×400).

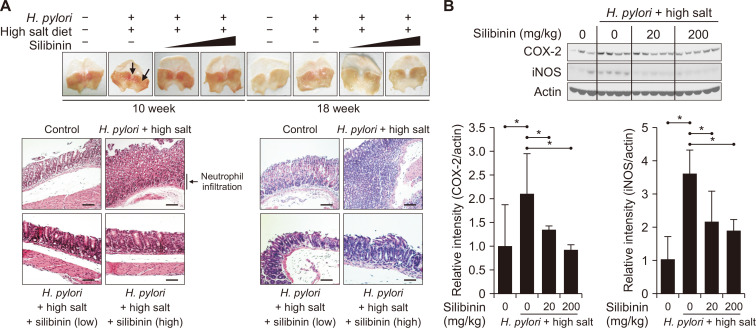

Silibinin ameliorates abnormal gross pathology of mouse stomach in H. pylori and high salt diet-induced gastritis

Besides cell culture experiments, we investigated the effect of silibinin on H. pylori-induced inflammation in mouse stomach. It was reported that H. pylori colonization in the stomach of mice fed high-salt diet was significantly higher than that of those fed normal diet [24,25]. Accordingly, we adopted an experimental design of H. pylori plus high salt diet [26]. We referred to several papers [27-29] for an optimal silibinin dose (20 mg/kg or 200 mg/kg). H. pylori infection in combination with high salt diet caused abnormal stomach morphology, neutrophil infiltration, and dysplasia and hyperplasia in mouse stomach, and these pathological manifestations were attenuated by silibinin administration (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. Protective effects of silibinin on gastritis induced by Helicobacter pylori plus high salt diet in mouse stomach.

(A) To induce gastritis, mice were inoculated with H. pylori (1 × 108 CFUs/100 µL) 5 times and given high salt diet (7.5%) for 4 weeks, which was followed by administration of silibinin for 4 weeks or 8 weeks. Mice tissues were stained with H&E (magnification: ×200). Scale bar, 200 µm. Arrows indicate the inflamed sites. (B) After 10 weeks, mouse stomach tissues were collected and lysed for Western blot analysis of COX-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression. Immunoblots were subjected to statistical analysis. *Significantly different between the groups compared (P < 0.05).

Silibinin inhibits H. pylori-induced expression of COX-2 and iNOS in mouse stomach

To clarify how silibinin could relieve these abnormal gross pathologies, stomach tissues of each treatment group were subjected to Western blot analysis. Compared with the control mice, mice inoculated with H. pylori and fed high salt diet revealed significantly elevated levels of COX-2 and iNOS in mouse stomach. Oral administration of silibinin resulted in a significantly reduced level of both COX-2 and iNOS. Therefore, the attenuation of the abnormal gross pathology reflecting dysplasia and hyperplasia by silibinin is likely to be attributed to the down-regulation of pro-inflammatory enzymes, COX-2 and iNOS (Fig. 6B).

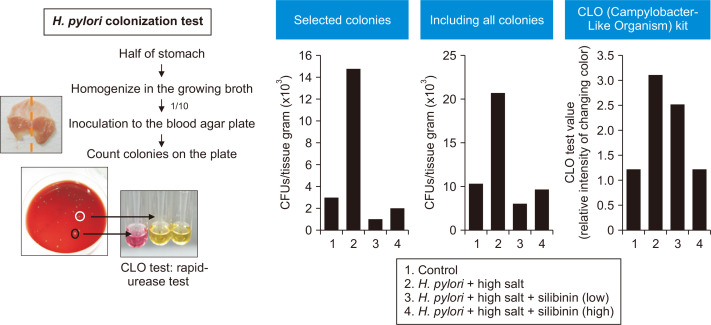

Silibinin has antibacterial effects against H. pylori infection in mouse stomach

All the aforementioned results demonstrate the inhibitory effects of silibinin on H. pylori-induced pro-inflammatory signaling. We speculated that the possible gastroprotective effects of silibinin are attributable not only to anti-inflammatory effects but also to an anti-bacterial activity. To evaluate possible anti-bacterial effects of silibinin, the H. pylori colonization test and the CLO kit test were conducted using an isolated mouse stomach tissue as described previously [30]. The levels of colonization were expressed numerically by counting colony-forming units per gram of mouse stomach tissue. There were a few types of colonies in different morphologies. To determine which colonies were infected by H. pylori, we performed the CLO test. The change in the color from yellow to red was indicative of colonization. The numbers of all colonies and selected colonies were dramatically increased in the H. pylori plus high salt diet group, and silibinin reduced the level of colonization (Fig. 7). Moreover, the color changing grade reflecting the degree of H. pylori infection was increased in the H. pylori plus high salt diet group compared with the control group when determined by the CLO test kit. Administration of silibinin resulted in a decrease of color changing grade in the CLO kit. Taken together, protective effects of silibinin against H. pylori-induced gastritis might be due to its direct bactericidal effects as well as anti-inflammatory activity.

Figure 7. Inhibitory effects of silibinin on colonization of Helicobacter pylori in mouse stomach as determined by the Campylobacter-Like Organism (CLO) test.

Half of the stomach specimens were placed in 1 mL of broth and homogenized with an UltraTurrax homogenizer. Ten-fold dilutions were made and 100 µL aliquots of the dilutions were placed onto blood agar plates. Bacterial counts were expressed as colony-forming units per gram of tissue. Counting of selected colonies and all colonies on the plate. The color changing grade determined by the CLO kit.

DISCUSSION

Helicobacter pylori infection is known to induce gastritis and gastric cancer [31]. Once H. pylori survive in acidic environment of the stomach, the bacterium enters the mucus layer and releases cytotoxins such as cytotoxin-associated agntigen A and vacuolating cytotoxin A that mediate proinflammatory signaling [32]. Combination of several antibiotics has been most frequently employed to eradicate H. pylori, but it may cause serious side effects [33]. Considering the unavoidable side effects of the synthetic antibiotics, we have been interested in searching for some phytochemicals with anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties as alternatives for the management H. pylori-induced gastritis and gastric cancer. One of the candidates is silibinin which is a component of silymarin mixture [13,34].

Silibinin has been reported to inhibit COX-2 and iNOS in an azoxymethane-induced mouse colon cancer model [35] and to down-regulate COX-2 in rat hepatocellular carcinoma [36]. The aforementioned publications address the possibility that silibinin could inhibit H. pylori-induced inflammation. We speculate that H. pylori-induced inflammation is mediated by NF-κB and STAT3, which might be inhibited by silibinin in MKN-1 cells and H. pylori-infected mouse stomach. Increased expression of COX-2 and iNOS and their mRNA transcripts induced by H. pylori was attenuated by silibinin. The suppression of pro-inflammatory signaling molecules, such as COX-2 and iNOS, by silibinin might be regulated at the transcriptional level. Since NF-κB plays a major role in transcriptional regulation of many pro-inflammatory enzymes and cytokines, we have focused on this transcription factor as a potential target of silibinin in its suppression of H. pylori-induced inflammation. H. pylori-induced nuclear translocation and DNA binding of NF-κB were inhibited by pretreatment with silibinin. Another transcription factor that is known to be implicated inflammation-associated carcinogenesis is STAT3.

Interplay or crosstalk between NF-κB and STAT3 attracted special attention in inflammation-associated carcinogenesis [37]. Multiple interactions between NF-κB and STAT3 could contribute to the promotion of cancer [38]. Moreover, the interaction between p65 and unphosphorylated STAT3 is prominent in the expression of inflammatory genes [39]. There are several possibilities that the Rel A/p65 subunit of NF-κB directly interacts with either unphosphorylated or phosphorylated STAT3 to regulate transcription of a target gene. p65 and STAT3 may work independently of each other, but provokes synergistic effects by interacting with the same promoter region of a single common target gene [40-42].

According to the findings from our present study, H. pylori could induce nuclear translocation and DNA binding of both NF-κB and STAT3. In an attempt to verify the interplay between NF-κB and STAT3 in H. pylori-induced inflammation and subsequent carcinogenesis in mouse stomach, we predicted the transcription factor binding sites of the COX-2 promoter using the TRANSFAC database. Several transcription factors could bind to the COX promoter. Based on this prediction, further studies will be necessary to ensure that the cross-talk between p65 and P-STAT3 could contribute to COX-2 expression in H. pylori-induced gastritis and that silibinin could break such an interplay.

In the mouse gastritis caused by H. pylori and high salt diet, silibinin administration ameliorated abnormal gross pathology. It seems likely that attenuation of an abnormal morphology by silibinin administration might be attributed to its down-regulation of inflammatory enzymes such as COX-2 and iNOS. In addition, silibinin has antibiotic effects as evidenced by decreased H. pylori colonization in mouse stomach treated with this phytochemical. These findings, taken all together, suggest that silibinin could be used as a potential chemopreventive agent or in the adjuvant therapy against H. pylori–induced gastritis or gastric cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Global Core Research Center (GCRC) grant (No. 2011-0030001) and BK21 FOUR Program (5120200513755) from the National Research Foundation, Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yamaoka Y. Roles of the plasticity regions of Helicobacter pylori in gastroduodenal pathogenesis. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57(Pt 5):545–53. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/000570-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGowan CC, Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and gastric acid: biological and therapeutic implications. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:926–38. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8608904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butcher LD, den Hartog G, Ernst PB, Crowe SE. Oxidative stress resulting from Helicobacter pylori infection contributes to gastric carcinogenesis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;3:316–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding SZ, Minohara Y, Fan XJ, Wang J, Reyes VE, Patel J, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection induces oxidative stress and programmed cell death in human gastric epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2007;75:4030–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00172-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardbower DM, de Sablet T, Chaturvedi R, Wilson KT. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress: the smoking gun for Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric cancer? Gut Microbes. 2013;4:475–81. doi: 10.4161/gmic.25583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ji Z, He L, Regev A, Struhl K. Inflammatory regulatory network mediated by the joint action of NF-kB, STAT3, and AP-1 factors is involved in many human cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:9453–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821068116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan Y, Mao R, Yang J. NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways collaboratively link inflammation to cancer. Protein Cell. 2013;4:176–85. doi: 10.1007/s13238-013-2084-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aggarwal BB. Nuclear factor-kappaB: the enemy within. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:203–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfitzner E, Kliem S, Baus D, Litterst CM. The role of STATs in inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:2839–50. doi: 10.2174/1381612043383638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bharadwaj U, Kasembeli MM, Robinson P, Tweardy DJ. Targeting Janus Kinases and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 to treat inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer: rationale, progress, and caution. Pharmacol Rev. 2020;72:486–526. doi: 10.1124/pr.119.018440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meurer LN, Bower DJ. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:1327–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tak PP, Firestein GS. NF-kappaB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:7–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI11830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh RP, Agarwal R. Cosmeceuticals and silibinin. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27:479–84. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramasamy K, Agarwal R. Multitargeted therapy of cancer by silymarin. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:352–62. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurley BJ, Barone GW, Williams DK, Carrier J, Breen P, Yates CR, et al. Effect of milk thistle (Silybum marianum) and black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) supplementation on digoxin pharmacokinetics in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:69–74. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh RP, Agarwal R. A cancer chemopreventive agent silibinin, targets mitogenic and survival signaling in prostate cancer. Mutat Res. 2004;555:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan AQ, Khan R, Tahir M, Rehman MU, Lateef A, Ali F, et al. Silibinin inhibits tumor promotional triggers and tumorigenesis against chemically induced two-stage skin carcinogenesis in Swiss albino mice: possible role of oxidative stress and inflammation. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66:249–58. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2014.863365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deep G, Agarwal R. Targeting tumor microenvironment with silibinin: promise and potential for a translational cancer chemopreventive strategy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2013;13:486–99. doi: 10.2174/15680096113139990041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuhara K, Osugi H, Takada N, Takemura M, Lee S, Morimura K, et al. Effect of H. pylori on COX-2 expression in gastric remnant after distal gastrectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1515–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JM, Kim JS, Jung HC, Oh YK, Chung HY, Lee CH, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection activates NF-kappaB signaling pathway to induce iNOS and protect human gastric epithelial cells from apoptosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G1171–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00502.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109 Suppl:S81–96. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aggarwal BB, Kunnumakkara AB, Harikumar KB, Gupta SR, Tharakan ST, Koca C, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription-3, inflammation, and cancer: how intimate is the relationship? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1171:59–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson DE, O'Keefe RA, Grandis JR. Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:234–48. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fox JG, Dangler CA, Taylor NS, King A, Koh TJ, Wang TC. High-salt diet induces gastric epithelial hyperplasia and parietal cell loss, and enhances Helicobacter pylori colonization in C57BL/6 mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4823–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers AB, Taylor NS, Whary MT, Stefanich ED, Wang TC, Fox JG. Helicobacter pylori but not high salt induces gastric intraepithelial neoplasia in B6129 mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10709–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yanaka A, Fahey JW, Fukumoto A, Nakayama M, Inoue S, Zhang S, et al. Dietary sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprouts reduce colonization and attenuate gastritis in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice and humans. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:353–60. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu P, Mamiya T, Lu LL, Mouri A, Zou L, Nagai T, et al. Silibinin prevents amyloid beta peptide-induced memory impairment and oxidative stress in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:1270–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu P, Mamiya T, Lu LL, Mouri A, Niwa M, Hiramatsu M, et al. Silibinin attenuates amyloid beta(25-35) peptide-induced memory impairments: implication of inducible nitric-oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:319–26. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.155069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh RP, Gu M, Agarwal R. Silibinin inhibits colorectal cancer growth by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2043–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee A, O'Rourke J, De Ungria MC, Robertson B, Daskalopoulos G, Dixon MF. A standardized mouse model of Helicobacter pylori infection: introducing the Sydney strain. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1386–97. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(97)70155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, Chang Y, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konturek PC, Konturek SJ, Brzozowski T. Helicobacter pylori infection in gastric cancerogenesis. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60:3–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salcedo JA, Al-Kawas F. Treating Helicobacter pylori. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2396–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.8.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bittencourt MLF, Rodrigues RP, Kitagawa RR, Gonçalves RCR. The gastroprotective potential of silibinin against Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric tumor cells. Life Sci. 2020;256:117977. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velmurugan B, Singh RP, Tyagi A, Agarwal R. Inhibition of azoxymethane-induced colonic aberrant crypt foci formation by silibinin in male Fisher 344 rats. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2008;1:376–84. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramakrishnan G, Elinos-Báez CM, Jagan S, Augustine TA, Kamaraj S, Anandakumar P, et al. Silymarin downregulates COX-2 expression and attenuates hyperlipidemia during NDEA-induced rat hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;313:53–61. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9741-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Surh YJ, Bode AM, Dong Z. Breaking the NF-κB and STAT3 alliance inhibits inflammation and pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:1379–81. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J, Stark GR. Roles of unphosphorylated STATs in signaling. Cell Res. 2008;18:443–51. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grivennikov SI, Karin M. Dangerous liaisons: STAT3 and NF-kappaB collaboration and crosstalk in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kovacic JC, Gupta R, Lee AC, Ma M, Fang F, Tolbert CN, et al. Stat3-dependent acute Rantes production in vascular smooth muscle cells modulates inflammation following arterial injury in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:303–14. doi: 10.1172/JCI40364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu Z, Zhang W, Kone BC. Signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3) inhibits transcription of the inducible nitric oxide synthase gene by interacting with nuclear factor kappaB. Biochem J. 2002;367(Pt 1):97–105. doi: 10.1042/bj20020588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]