Abstract

Objective:

Delirium is a common condition associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Medication side effects are a possible source of modifiable delirium risk and provide an opportunity to improve delirium predictive models. This study characterized the risk for delirium diagnosis by applying a previously validated algorithm for calculating central nervous system adverse effect burden arising from a full medication list.

Method:

Using a cohort of hospitalized adult (age 18-65) patients from the Massachusetts All-Payers Claims Database, we calculated medication burden following hospital discharge and characterized risk of new coded delirium diagnosis over the following 90 days. We applied the resulting model to a held-out test cohort.

Results:

The cohort included 62,180 individuals of whom 1.6% (1,019) went on to have a coded delirium diagnosis. In the training cohort (43,527 individuals), the medication burden feature was positively associated with delirium diagnosis (OR=5.75, 95% CI 4.34–7.63) and this association persisted (aOR=1.95; 1.31–2.92) after adjusting for demographics, clinical features, prescribed medications, and anticholinergic risk score. In the test cohort, the trained model produced an area under the curve of 0.80 (0.78–0.82). This performance was similar across subgroups of age and gender.

Conclusion:

Aggregating brain-related medication adverse effects facilitates identification of individuals at high risk of subsequent delirium diagnosis.

Keywords: Delirium, pharmacovigilance, data mining, predictive modeling, feature engineering, cohort study

1. Introduction

Delirium is an acute confusional state arising in the context of medical illness through an incompletely understood multifactorial process.[1-4] This common and consequential cognitive manifestation of illness is of particular concern to consulting psychiatrists and increasingly discussed in subspeciality geriatrics and critical care literatures,[5-7] as it has been associated with both increased mortality and morbidity.[8] Delirium is associated with longer mechanical ventilation, longer length of hospital stay, longer intensive care unit stays, increased rate of institutional discharge, increased risk of readmission, lower post-hospital health-related quality of life, and post-hospital cognitive deficits.[9-18] Delirium is also associated with increases in medical expense to society,[19-23] is aversive to patients and their families, and is a source of increased caregiver burden for clinical staff.[24-32] Fortunately, multicomponent interventions are able to reduce rates of delirium in some groups.[33-35]

Among the most commonly recognized risk factors for delirium are medication-associated adverse effects.[4,36-39] Medication associated risk is of particular interest because it is modifiable and that modification could occur on the timescale of acute care hospitalization or elective surgery optimization as a portion of recommended prevention programs.[40] Multiple approaches to identifying medications associated with risk have been developed, generally on the basis of expert manual curation.[41,42] In particular, some of these curated lists emphasize anticholinergic medications which are theorized to be of potentially greater relevance to delirium;[43-45] however, studies of human subjects do not consistently identify associations among anticholinergic risk scales and delirium.[46,47]

We have previously described and validated a scalable method for calculating cumulative medication burden for particular categories of adverse effects using FDA labeling and demonstrated that medication burden score could accurately predict risk for future fall.[48,49] Here, we sought to understand whether this approach to medication burden scoring could also predict delirium risk following hospital discharge. We utilized Massachusetts state discharge records to characterize the association automated risk score, in the context of additional sociodemographic and clinical features.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cohort Development

This study of adult patients hospitalized for acute inpatient care drew data from the Massachusetts All-Payer Claims Database (APCD). This database includes claims paid for Massachusetts residents independent of insurance type. The Massachusetts APCD data available for this study did not include Medicare payments and thus the cohort was limited to those less than 65 years of age. All other adults discharged alive from a medical or surgical inpatient admission were considered and all APCD claims data, whether paid through public or private payers, were included. Billing data were used to identify inpatient acute care hospitalizations as the cohort entry defining event. The index visit was defined as the first hospital discharge during the observation period (1 January 2012 and 31 December 2012) with subjects entered the study cohort following their first discharge from acute care. As the study focused on medication associated risk, those who had no medications prescribed at index admission were excluded. The study using non-identifying preexisting clinical data was granted a waiver of informed consent under 45 CFR 46.116.

2.2. Clinical Data Handling

The primary study outcome was delirium diagnosis within 90 days of hospital discharge. Only patients with adequate follow-up to observe the primary outcome were considered. To facilitate interpretation with prior publications, delirium was defined as any of International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes 290.(11,3,41), 293.(0,1,9), or 780.09.[50,51] The original development of this APCD delirium definition considered but did ultimately not include the comparably heterogeneous encephalitis codes.[51,52] Additional demographic and clinical factors were extracted for analysis including age, sex, insurance type (commercial vs. public), the duration of hospitalization (in days), and whether the admission occurred through an emergency department. Coded diagnostic history was used to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index and to identify patients with a history of neuropsychiatric diagnosis.[53] These were selected as the intersection of delirium risk factors and available data.[37,46,54-56] Hospital diagnostic claims data were used to identify patients who had a delirium diagnosis during the index hospitalization. Prescription medication data were extracted and handled as described subsequently. For financial analysis all medical expenses incurred after index hospitalization were summed and then normalized to the number of post-hospital days over which these expenses could have been incurred.

2.3. Medication Data and Feature Engineering

Medications in APCD do not distinguish between those prescribed at hospital discharge or following hospital discharge. Therefore, any prescription filled within 15 days of hospital discharge was considered a probable discharge medication and analyzed as a hospital medication for risk scoring. To allow for this 15-day window of medication data to accumulate, patients with events prior to 15 days were excluded from the analysis. Prescribed medications were walked back to prescribed ingredients and those ingredients deduplicated. In other words, a combination medication – for example, one including both acetaminophen and an opioid in a single table – would be expanded to two unique ingredients but multiple prescriptions of a single ingredient – for example, acetaminophen in isolation and in combination – only counted once. Three medication-related features were derived from this unique prescribed ingredient list: (1) the total number of prescribed agents as a simple count, (2) the cumulative Rudolph anticholinergic risk scale score for the list,[44] and (3) a custom delirium medication burden score.[48,49] Although analogous to prior work on falls, this delirium medication burden score assigns different weights to the prescriptible ingredients; as in prior work, we assume additivity of ingredient level burden scores. For example, tiotropium has a calculated delirium burden score of .0005, cyclobenzaprine of 1.78, and alprazolam of 3.38 and thus a patient taking all three would have a crude net burden score of 5.16. The full list of delirium burden scores calculated for each ingredient is shown in Supplemental Table 1.

The delirium medication burden score is a cumulative measure of medication side effects thought by experts to increase the risk of central nervous system (CNS) complications. This measure is the sum of the frequencies of CNS associated side effects reported for each medication a patient is taking. The frequencies of each side effect for each prescribed ingredient were drawn from the SIDER Side Effect Resource databases. The SIDER database maps medications to the frequency of individual side effects associated with those medications using medication labels and post-marketing surveillance data. The custom Burden Score represents an expert-informed summary of how likely a patient is to experience delirium relevant side effects based on the reported frequency of each adverse effect in medication labeling. The minimum score is 0 (no associated adverse effects) with no upper bound, with the assumption that adverse effect frequencies are additive. The assumption of adverse effect additivity is such that if two medications are labeled as being associated with confusion in 10% of patients, a patient treated with both would have a medication burden score of 0.2; if an additional medication also had a 5% frequency of light-headedness, then the burden score would increase to 0.25. This summative medication burden approach has previously been developed and reported for fall risk prediction and independently validated in the APCD.[48,49]

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The full patient cohort was randomly partitioned into a training set for model fitting (70%) and testing set for model prediction evaluation (30%). Descriptive statistics appropriate to each data element type were used to characterize the study cohorts. Multivariable logistic regression was selected as the primary model of the association between medication burden and delirium diagnosis as it provides readily interpretable adjusted odds ratios (aOR) in the training set and extends directly to the prediction of delirium diagnosis in the testing set. Random forest and naive Bayes classifiers were selected as sensitivity checks on the choice of logistic regression as the primary predictive model. The feature variables included in the model were selected as the intersection of variables of known clinical significance and available data elements. As a sensitivity check on the model specification and evaluation of the utility of the medication burden feature of primary interest, forward and backwards stepwise selection by Akaike information criterion was used to evaluate features contributing to model fit.[57] Alternative outcomes of delirium within 60 days of index hospital discharge and 180 days of hospital discharge were evaluated as a sensitivity check on the choice of 90 days as the primary outcome.

Cross-sectional predictive accuracy was assessed by area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), conventional analysis of sensitivity and specificity, and finally through lift – a comparison between the overall sample event rate and quantiles of predicted risk. Secondary analysis of predictive accuracy across subgroups focused on AUCs by sex and age group. In addition to cross-sectional accuracy, stratified Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank testing was used to evaluate the longitudinal risk stratification potential of the resulting model.

In addition to the primary analysis of the multivariable logistic regression model the medication burden score was evaluated isolation. This parallel analysis included calculation of univariable odds of the delirium outcome and AUC of the raw medication burden score as an uncalibrated univariable predictor. Finally, the relationship between the medication burden score and total post-hospital medical expenses per day of potential follow-up available adjusting for private or public insurance, age, and sex was evaluated using multivariable linear regression.

Anticholinergic risk score, total number of medications, medication burden score, Charlson comorbidity index, length of stay, and medical expenses per day were all log transformed due to right skew. All analysis were completed using R v3.

3. Results

The full study cohort included 62,180 individuals with 43,527 randomly allocated to the training set and 18,653 randomly allocated to the test set (Table 1). The full cohort (Table 1, left) was 43.8% male (27,221 of 62,180) and the average age was 51.9 years (SD 8.7) during the index admission. Delirium was present in 0.8% of index admissions (520 of 62,180) admissions and the primary outcome of delirium diagnosis within 90 days of hospital discharge occurred in 1.6% (1,019 of 62,180) of all cases. A history of neuropsychiatric diagnosis in the six months prior to index admission was present in 46.7% (29,016 of 62,180) patients. The average number of medications prescribed during the hospital stay and subsequent fifteen days was 4.50 (SD = 3.18) and the average anticholinergic risk score was 0.38 (SD = 0.97). The average medication burden score was 1.20 (SD = 1.49). Characteristics were similar across the randomly allocated testing and training cohorts (Table 1, center and right).

Table 1:

Sociodemographic characteristics of the full eligible sample (left) contrasted by testing (center) and training (right) cohort.

| Total N = 62180 |

Test N = 18653 |

Train N = 43527 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Delirium outcome - n (%) | 1019 (1.6) | 305 (1.6) | 714 (1.6) |

| Private Insurance - n (%) | 26274 (42.3) | 7890 (42.3) | 18384 (42.2) |

| Patient admitted from ED - n (%) | 26647 (42.9) | 8037 (43.1) | 18610 (42.8) |

| Prior Neuropsychiatric Diagnosis - n (%) | 29016 (46.7) | 8712 (46.7) | 20304 (46.6) |

| Delirium at index admission - n (%) | 520 (0.8) | 171 (0.9) | 349 (0.8) |

| Sex (Male) - n (%) | 27221 (43.8) | 8138 (43.6) | 19083 (43.8) |

| Age at admission (years) - mean (SD) | 51.89 (8.68) | 51.91 (8.69) | 51.88 (8.68) |

| Charlson comorbidity index - mean (SD) | 4.99 (8.26) | 4.95 (8.23) | 5.01 (8.28) |

| Length of stay (days) - mean (SD) | 3.51 (2.79) | 3.52 (2.78) | 3.51 (2.80) |

| Total prescribed medications - mean (SD) | 4.50 (3.18) | 4.51 (3.17) | 4.50 (3.18) |

| Anticholinergic risk score - mean (SD) | 0.38 (0.97) | 0.38 (0.98) | 0.38 (0.97) |

| Medication burden score - mean (SD) | 1.20 (1.49) | 1.18 (1.48) | 1.20 (1.50) |

Abbreviations: ED = Emergency Department

The logistic regression model fitted to the training test set is shown in Table 2. The medication burden score was positively and significantly associated (aOR = 1.95, 95% CI 1.31 – 2.92) with subsequent delirium diagnosis after adjusting for clinical and sociodemographic factors, whereas neither medication number nor anticholinergic risk score were significantly associated with delirium. Consistent with expectations based on literature, older age (aOR = 1.02, 95% CI 1.01 – 1.03), male sex (aOR = 1.41, 95% CI 1.21 – 1.64), greater illness burden as captured by Charlson comorbidity index (aOR = 2.53, 95% CI 2.13 – 3.00), history of neuropsychiatric illness (aOR = 1.71, 95% CI 1.43 – 2.06), longer hospitalization (aOR = 2.30, 95% CI 1.66 – 3.18), and admission via the emergency department (aOR=1.50, 95% CI 1.27 – 1.77) were all associated with delirium diagnosis within 90 days (Table 2). Sensitivity analysis of the outcome replacing the 90-day outcome with 60- and 180-day delirium outcomes were consistent with the primary analysis (not shown).

Table 2:

Logistic regression model of 90-day delirium outcome fitted in the training cohort.

| Predictors | Odds Ratios |

CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private Insurance | 2.9 | 2.29 – 3.67 | <0.001 |

| Patient admitted from ED | 1.5 | 1.27 – 1.77 | <0.001 |

| Prior Neuropsychiatric Diagnosis | 1.71 | 1.43 – 2.06 | <0.001 |

| Delirium at index admission | 2.06 | 1.35 – 3.15 | 0.001 |

| Sex - Male | 1.41 | 1.21 – 1.64 | <0.001 |

| Age at admission | 1.02 | 1.01 – 1.03 | 0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index ^ | 2.53 | 2.13 – 3.00 | <0.001 |

| Length of Stay ^ | 2.3 | 1.66 – 3.18 | <0.001 |

| Total prescribed medications ^ | 0.84 | 0.57 – 1.25 | 0.398 |

| Anticholinergic risk score ^ | 1.05 | 0.72 – 1.53 | 0.812 |

| Medication burden score ^ | 1.95 | 1.31 – 2.92 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: ED = Emergency Department

log transformed

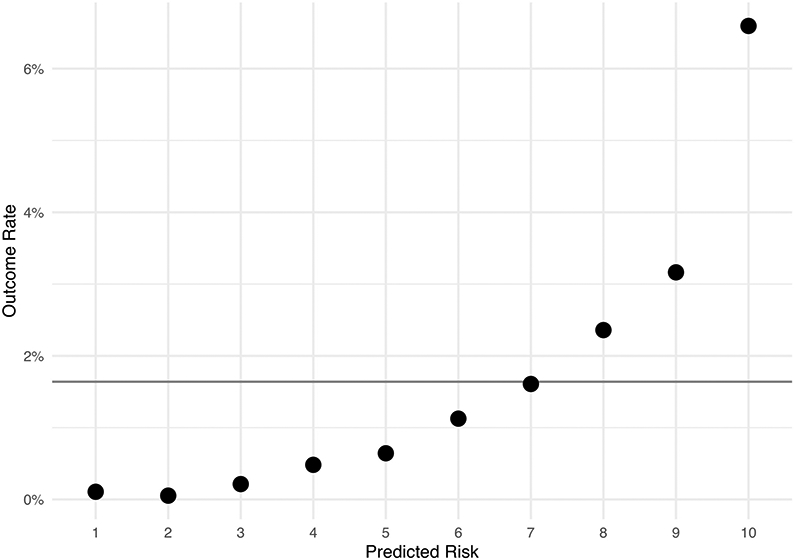

Next, we evaluated the quality of predictions made by the logistic regression model using the independent test set. The test set produced an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI 0.78 - 0.82). The lift in the top decile of predictive risk was 4x, versus .07x in the bottom decile (Figure 1). The highest predicted risk 10% of test set patients accounted for 40% (123 of 305) of cases whereas the bottom 50% of test set patients only included 9% (28 of 305) cases. A sensitivity of 80% occurred at a prediction threshold of 0.012 and produced a specificity of 65%. In secondary subgroup analysis within the test set the AUCs in male patients (0.77, 95% CI 0.74 - 0.80) and female (0.82, 95% CI 0.79 - 0.85) patients were similar as were those across age groups: 0.84 (0.95 CI 0.80 - 0.88) in 35-45-year-olds, 0.79 (0.95 CI 0.75 - 0.83) in 46-55-year-olds, and 0.77 (0.95 CI 0.73 - 0.81) in 56-65-year-olds. For comparison to logistic regression, we trained a random forest and naive Bayes classifier using the same testing cohort and predictive variables and then evaluated these in the training set, producing equivalent AUCs of 0.79 (95 CI 0.77 - 0.81) and 0.79 (95 CI 0.77 - 0.81) respectively. As a final predictive metric, we evaluated the utility of cross-sectional logistic regression predictions in time to delirium outcomes risk stratification. In this analysis, quartile of predicted delirium risk was significantly associated with time to event by log rank test (χ2 = 697; p < .001; Figure 2a).

Figure 1:

Predictive lift by decile of predicted risk in the independent testing set

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meier curves of time to delirium outcome in the testing cohort stratified by (A) quartile of predicted delirium risk and (B) quartile of raw univariate medication burden score.

The medication burden score was independently associated with the delirium outcome (OR=5.75, 95% CI 4.34 – 7.63) in the training set in a univariate model. When the raw burden score was used directly as a delirium risk score it produced an AUC of 0.60 (95 CI 0.56 - 0.64) in the testing set. Quartile of raw medication burden score was significantly associated with time to delirium outcome (χ2 = 148; p <.001; Figure 2b). Sensitivity analysis of the multivariable model’s variables by forward and also backwards stepwise selection converged on the same model: inclusion of all variables except total number of medications and anticholinergic risk score—the medication burden score was included as a predictor of the outcome in both automatic selection methods. Finally, in a linear regression of medical cost on medication burden score, adjusted for age, sex, and private insurance, greater medication burden was associated with greater medical costs in both the training (Est = 0.50, 95% CI 0.47 – 0.53) and the test sets (Est = 0.44, 95% CI 0.39 – 0.48). The median daily expenditure in the bottom half of medication burden scores was $70.25 [68.56-71.97], whereas the median daily expenditure in the top 10% of medication burden scores was $178.40 [172.10-185.00].

4. Discussion

In this study of 62,180 individuals discharged from Massachusetts hospitals, a medication burden score based on adverse effect data was significantly associated with the risk of subsequent delirium diagnosis. In a held-out testing set, the predictive accuracy of the model was consistent with those reported in previous delirium prediction studies[58] and prior work demonstrating similar association between medication burden and post hospital fall risk.[48,49] This result supports two potential applications: first, a new approach to medication associated delirium risk captured in the medication burden feature; and second, a potential enhancement to delirium diagnosis risk stratification useful in guiding evidence-based prevention efforts.

Current guidelines and reviews favor multicomponent delirium prevention programs;[35,40,59-62] however, these interventions require ongoing operational resources and in existing reports are not associated with shorter hospital admissions or reduced institutionalization.[34,35] Predictive models of the sort reported here could facilitate more optimal referrals into such efforts by stratifying individuals at greatest risk while the medication burden feature could simultaneously guide a targeted medication risk reduction effort. The AUC of 0.80 in the held-out test cohort is at the upper end of previously reported delirium prediction model AUCs (0.52-0.94) covered in systematic review and that (0.71–0.79) of a more intensive recent machine learning effort.[58,63]

Polypharmacy is a frequently identified risk factor for delirium;[4,36-39] however, crude medication number as a risk factor gives no guidance on prioritizing among medications for targeted risk minimization efforts. In this cohort the association between delirium and the medication burden score was statistically significant whereas the associations between delirium diagnosis and both total number of medications and anticholinergic risk were not. This differential association in favor of medication burden may point the way toward more precise targeted management of medication associated delirium risk. Previous reports have linked specific medication classes (e.g., benzodiazepines) to delirium risk;[64-66] however, class level medication prohibitions are of limited clinical utility as therapeutic intent and adverse effects are correlated at the class level and thus the prescriber’s challenge is often in balancing effect and side-effect when constrained to a single class.[67,68] Among classes, the anticholinergic medications have been of particular focus in the delirium literature and thus have a more developed within-class literature.[44,45] Notably, the lack of association between anticholinergic risk and delirium is consistent with previous studies reporting a lack of association between anticholinergics and delirium.[43,46,47] Whereas prior efforts focused on medication risk stratification required considerable class specific per agent effort, the approach reported here is outcome specific and thereafter scales over all medication without additional effort.[43,44] As comprehensive burden scoring of the sort reported here captures both the additive effect of polypharmacy and the differential contribution of individual agents—both within and across classes—in a fashion which can be scaled across the growing pharmacopeia, burden scoring may be a generally useful approach to an outcome specific quantification of polypharmacy risk and prescription risk mitigation.

In interpreting our results, multiple inherent limitations must be considered. First, we rely on administrative claims of delirium diagnosis which do not accurately identify all clinical case delirium; instead, coded diagnosis typically under report actual delirium.[51,69,70] Undercoding may be particularly true for milder and more subacute presentations.[52] However, we would anticipate that this misclassification would more likely cause us to underestimate the performance of our model due to incorrect classification of true cases as non-cases. Second, it is important to note that the correlation between medication burden score and the delirium outcome reported here does not imply a causal link such that modification of the delirium burden score by modifications to prescribed medication will necessarily alter delirium risk. This correlation could be confounded as modifiable high-risk medications may be proxies for unmodifiable underlying medical comorbidity that itself confers risk (i.e., an example of confounding by indication). Prospective clinical investigation will be required to determine whether a clinical effort to minimize a patient’s burden score actually reduces risk. However, our results do suggest that such studies should be considered as a means of preventing delirium. Ideally future work would include a prospective evaluation of predictive accuracy for an active bedside assessment of the delirium outcome. In parallel, although more complex to calculate, further analysis might consider the role of p450 interactions in delirium medication burdens.[71-73] Finally, the comprehensive state-wide data available for this report do not include elderly patients and thus further research will be needed to evaluate generalizability to the extensive geriatric delirium literature.[5] Risk factors for delirium, and delirium occurrence rates, vary by clinical population such that specific associations among risk factor should not be extended beyond the studied cohort.[51,74] In particular, the present cohort is unlikely to be representative of associations which depend on underlying age-related cognitive change.

4.1. Conclusions

Greater risk for delirium is associated with a greater cumulative medication burden score based on medication side effect data after adjusting for demographics, clinical features, anticholinergic risk score, and total number of medications. This scalable and easily implemented medication burden score could be incorporated into delirium prevention programs and provide an approach to balancing therapeutic intent and delirium risk. Clinical trials are required to establish whether reduction of medication burden scores through targeted pharmacologic optimization efforts translate to a reduction in subsequent cases of delirium.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH116270) The sponsors had no role in study design, writing of the report, or data collection, analysis, or interpretation.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Thomas H. McCoy, Jr reports grants from Telefonica Alpha, the Stanley Center at the Broad Institute, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the National Institute of Mental Health. Roy H. Perlis has served on advisory boards or provided consulting to Genomind, Psy Therapeutics, RIDVentures, and Takeda. He receives salary support from JAMA Network-Open for service as Associate Editor. He holds equity in Psy Therapeutics and Outermost Therapeutics. He reports research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, and National Human Genomics Research Institute. Kamber Hart and Victor Castro have no disclosures to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Maldonado JR. Delirium pathophysiology: An updated hypothesis of the etiology of acute brain failure. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2018;33:1428–57. 10.1002/gps.4823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nature Reviews: Neurology 2009;5:210–20. 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Inouye SK, Charpentier PA Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons. Predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA 1996;275:852–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].McCoy TH Mapping the Delirium Literature Through Probabilistic Topic Modeling and Network Analysis: A Computational Scoping Review. Psychosomatics 2019;60:105–20. 10.1016/j.psym.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Taylor JB, Stern TA Meeting Its Mission: Does Psychosomatics Align With the Mission of Its Parent Organization, the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine? Psychosomatics 2017;58:375–85. 10.1016/j.psym.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nisavic M, Shuster JL, Gitlin D, Worley L, Stern TA Readings on Psychosomatic Medicine: Survey of Resources for Trainees. Psychosomatics 2015;56:319–28. 10.1016/j.psym.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M, Primeau F, Belzile E Delirium predicts 12-month mortality. Archives of Internal Medicine 2002;162:457–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zhang Z, Pan L, Ni H Impact of delirium on clinical outcome in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013;35:105–11. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gleason LJ, Schmitt EM, Kosar CM, Tabloski P, Saczynski JS, Robinson T, et al. Effect of Delirium and Other Major Complications on Outcomes After Elective Surgery in Older Adults. JAMA Surg 2015;150:1134–40. 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Koster S, Hensens AG, van der Palen J The long-term cognitive and functional outcomes of postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;87:1469–74. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.02.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].van den Boogaard M, Schoonhoven L, Evers AWM, van der Hoeven JG, van Achterberg T, Pickkers P Delirium in critically ill patients: impact on long-term health-related quality of life and cognitive functioning. Crit Care Med 2012;40:112–8. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822e9fc9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Khouli H, Astua A, Dombrowski W, Ahmad F, Homel P, Shapiro J, et al. Changes in health-related quality of life and factors predicting long-term outcomes in older adults admitted to intensive care units. Crit Care Med 2011;39:731–7. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318208edf8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wolters AE, van Dijk D, Pasma W, Cremer OL, Looije MF, de Lange DW, et al. Long-term outcome of delirium during intensive care unit stay in survivors of critical illness: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care 2014;18:R125. 10.1186/cc13929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Ely EW Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 2014;370:185–6. 10.1056/NEJMc1313886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Girard TD, Thompson JL, Pandharipande PP, Brummel NE, Jackson JC, Patel MB, et al. Clinical phenotypes of delirium during critical illness and severity of subsequent long-term cognitive impairment: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2018;6:213–22. 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30062-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Schubert M, Schürch R, Boettger S, Garcia Nuñez D, Schwarz U, Bettex D, et al. A hospital-wide evaluation of delirium prevalence and outcomes in acute care patients - a cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:550. 10.1186/s12913-018-3345-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Goldberg TE, Chen C, Wang Y, Jung E, Swanson A, Ing C, et al. Association of Delirium With Long-term Cognitive Decline: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol 2020. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zywiel MG, Hurley RT, Perruccio AV, Hancock-Howard RL, Coyte PC, Rampersaud YR Health Economic Implications of Perioperative Delirium in Older Patients After Surgery for a Fragility Hip Fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015;97:829–36. 10.2106/JBJS.N.00724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Milbrandt EB, Deppen S, Harrison PL, Shintani AK, Speroff T, Stiles RA, et al. Costs associated with delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Critical Care Medicine 2004;32:955–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, Leo-Summers L, Inouye SK One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Archives of Internal Medicine 2008;168:27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Vasilevskis EE, Chandrasekhar R, Holtze CH, Graves J, Speroff T, Girard TD, et al. The Cost of ICU Delirium and Coma in the Intensive Care Unit Patient. Medical Care 2018;56:890–7. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Leslie DL, Inouye SK The importance of delirium: economic and societal costs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2011;59:S241–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mossello E, Lucchini F, Tesi F, Rasero L Family and healthcare staff’s perception of delirium. Eur Geriatr Med 2020; 11:95–103. 10.1007/s41999-019-00284-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Day J, Higgins I Adult family member experiences during an older loved one’s delirium: a narrative literature review. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:1447–56. 10.llll/jocn.12771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Toye C, Matthews A, Hill A, Maher S Experiences, understandings and support needs of family carers of older patients with delirium: a descriptive mixed methods study in a hospital delirium unit. Int J Older People Nurs 2014;9:200–8. 10.1111/opn.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Morandi A, Lucchi E, Turco R, Morghen S, Guerini F, Santi R, et al. Delirium superimposed on dementia: A quantitative and qualitative evaluation of informal caregivers and health care staff experience. J Psychosom Res 2015;79:272–80. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Grossi E, Lucchi E, Gentile S, Trabucchi M, Bellelli G, Morandi A Preliminary investigation of predictors of distress in informal caregivers of patients with delirium superimposed on dementia. Aging Clin Exp Res 2020;32:339–44. 10.1007/s40520-019-01194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bruera E, Bush SH, Willey J, Paraskevopoulos T, Li Z, Palmer JL, et al. Impact of delirium and recall on the level of distress in patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. Cancer 2009;115:2004–12. 10.1002/cncr.24215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Breitbart W, Gibson C, Tremblay A The delirium experience: delirium recall and delirium-related distress in hospitalized patients with cancer, their spouses/caregivers, and their nurses. Psychosomatics 2002;43:183–94. 10.1176/appi.psy.43.3.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Morita T, Akechi T, Ikenaga M, Inoue S, Kohara H, Matsubara T, et al. Terminal delirium: recommendations from bereaved families’ experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;34:579–89. 10.1016/jjpainsymman.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fong TG, Racine AM, Fick DM, Tabloski P, Gou Y, Schmitt EM, et al. The Caregiver Burden of Delirium in Older Adults With Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:2587–92. 10.1111/jgs.16199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Khan A, Boukrina O, Oh-Park M, Flanagan NA, Singh M, Oldham M Preventing Delirium Takes a Village: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Delirium Preventive Models of Care. J Hosp Med 2019;14:E1–7. 10.12788/jhm.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hshieh TT, Yue J, Oh E, Puelle M, Dowal S, Travison T, et al. Effectiveness of multicomponent nonpharmacological delirium interventions: a meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine 2015;175:512–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hshieh TT, Yang T, Gartaganis SL, Yue J, Inouye SK Hospital Elder Life Program: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Effectiveness. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2018;26:1015–33. 10.1016/j.jagp.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kurisu K, Miyabe D, Furukawa Y, Shibayama O, Yoshiuchi K Association between polypharmacy and the persistence of delirium: a retrospective cohort study. Biopsychosoc Med 2020;14:25. 10.1186/s13030-020-00199-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Duning T, Ilting-Reuke K, Beckhuis M, Oswald D Postoperative delirium - treatment and prevention. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2021;34:27–32. 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kassie GM, Nguyen TA, Kalisch Ellett LM, Pratt NL, Roughead EE Preoperative medication use and postoperative delirium: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:298. 10.1186/s12877-017-0695-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Vasilevskis EE, Han JH, Hughes CG, Ely EW Epidemiology and risk factors for delirium across hospital settings. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2012;26:277–87. 10.1016/j.bpa.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Siddiqi N, Harrison JK, Clegg A, Teale EA, Young J, Taylor J, et al. Interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;3:CD005563. 10.1002/14651858.CD005563.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Marriott J, Stehlik P A critical analysis of the methods used to develop explicit clinical criteria for use in older people. Age Ageing 2012;41:441–50. 10.1093/ageing/afs064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].O’Mahony D, Gallagher PF Inappropriate prescribing in the older population: need for new criteria. Age Ageing 2008;37:138–41. 10.1093/ageing/afm189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Welsh TJ, van der Wardt V, Ojo G, Gordon AL, Gladman JRF Anticholinergic Drug Burden Tools/Scales and Adverse Outcomes in Different Clinical Settings: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Drugs Aging 2018;35:523–38. 10.1007/s40266-018-0549-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC, McGlinchey RE The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:508–13. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hshieh TT, Fong TG, Marcantonio ER, Inouye SK Cholinergic deficiency hypothesis in delirium: a synthesis of current evidence. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008;63:764–72. 10.1093/gerona/63.7.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Schor JD, Levkoff SE, Lipsitz LA, Reilly CH, Cleary PD, Rowe JW, et al. Risk factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly. JAMA 1992;267:827–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wolters AE, Zaal IJ, Veldhuijzen DS, Cremer OL, Devlin JW, van Dijk D, et al. Anticholinergic medication use and transition to delirium in critically ill patients: A prospective cohort study. Critical Care Medicine 2015;43:1846–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].McCoy TH, Castro VM, Cagan A, Roberson AM, Perlis RH Validation of a risk stratification tool for fall-related injury in a state-wide cohort. BMJ Open 2017;7:e012189. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Castro VM, McCoy TH, Cagan A, Rosenfield HR, Murphy SN, Churchill SE, et al. Stratification of risk for hospital admissions for injury related to fall: cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) 2014;349:g5863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].McCoy TH Jr, Chaukos DC, Snapper LA, Hart KL, Stern TA, Perlis RH Enhancing Delirium Case Definitions in Electronic Health Records Using Clinical Free Text. Psychosomatics 2017;58:113–20. 10.1016/j.psym.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].McCoy TH, Snapper L, Stern TA, Perlis RH Underreporting of Delirium in Statewide Claims Data: Implications for Clinical Care and Predictive Modeling. Psychosomatics 2016;57:480–8. 10.1016/j.psym.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Bui LN, Pham VP, Shirkey BA, Swan JT Effect of delirium motoric subtypes on administrative documentation of delirium in the surgical intensive care unit. Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing 2017;31:631–40. 10.1007/s10877-016-9873-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J Validation of a combined comorbidity index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1994;47:1245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Chen J, Yu J, Zhang A Delirium risk prediction models for intensive care unit patients: A systematic review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2020;60:102880. 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Dylan F, Byrne G, Mudge AM Delirium risk in non-surgical patients: systematic review of predictive tools. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2019;83:292–302. 10.1016/j.archger.2019.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Watt J, Tricco AC, Talbot-Hamon C, Pham B, Rios P, Grudniewicz A, et al. Identifying Older Adults at Risk of Delirium Following Elective Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33:500–9. 10.1007/s11606-017-4204-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].McCoy TH, Castro VM, Roberson AM, Snapper LA, Perlis RH Improving Prediction of Suicide and Accidental Death After Discharge From General Hospitals With Natural Language Processing. JAMA Psychiatry 2016;73:1064. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Lindroth H, Bratzke L, Purvis S, Brown R, Coburn M, Mrkobrada M, et al. Systematic review of prediction models for delirium in the older adult inpatient. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019223. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Nikooie R, Neufeld KJ, Oh ES, Wilson LM, Zhang A, Robinson KA, et al. Antipsychotics for Treating Delirium in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med 2019;171:485–95. 10.7326/M19-1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Oh ES, Needham DM, Nikooie R, Wilson LM, Zhang A, Robinson KA, et al. Antipsychotics for Preventing Delirium in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med 2019;171:474–84. 10.7326/M19-1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Neufeld KJ, Needham DM, Oh ES, Wilson LM, Nikooie R, Zhang A, et al. Antipsychotics for the Prevention and Treatment of Delirium. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, Luxenberg JS, Siddiqi N, Hutton B, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;6:CD005594. 10.1002/14651858.CD005594.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Castro VM, Sacks A, Perlis RH, McCoy TH Jr. Development and external validation of a delirium prediction model for hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Psychosomatics n.d.;[In Press]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Dubois MJ, Bergeron N, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y Delirium in an intensive care unit: a study of risk factors. Intensive Care Med 2001;27:1297–304. 10.1007/s001340101017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Marcantonio ER, Juarez G, Goldman L, Mangione CM, Ludwig LE, Lind L, et al. The relationship of postoperative delirium with psychoactive medications. JAMA 1994;272:1518–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Clegg A, Young JB Which medications to avoid in people at risk of delirium: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2011;40:23–9. 10.1093/ageing/afq140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Shaughnessy AF Prescribing for older adults: finding the balance. Am Fam Physician 2007;76:1768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Pham CB, Dickman RL Minimizing adverse drug events in older patients. Am Fam Physician 2007;76:1837–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Élie M, Rousseau F, Cole M, Primeau F, McCusker J, Bellavance F Prevalence and detection of delirium in elderly emergency department patients. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2000;163:977–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].van Eijk MMJ, van Marum RJ, Klijn IAM, de Wit N, Kesecioglu J, Slooter AJC Comparison of delirium assessment tools in a mixed intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine 2009;37:1881–5. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a00118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Thom RP, Levy-Carrick NC, Bui M, Silbersweig D Delirium. AJP 2019;176:785–93. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18070893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].McCoy TH, Castro VM, Cagan A, Snapper L, Roberson A, Perlis RH Cytochrome P450 interactions are common and consequential in Massachusetts hospital discharges. The Pharmacogenomics Journal 2017. 10.1038/tpj.2017.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].McCoy TH, Castro VM, Cagan A, Roberson AM, Perlis RH Prevalence and implications of cytochrome P450 substrates in Massachusetts hospital discharges. The Pharmacogenomics Journal 2016. 10.1038/tpj.2016.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].McCoy TH, Hart KL, Perlis RH Characterizing and predicting rates of delirium across general hospital settings. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2017;46:1–6. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.