Abstract

Female and male infertility have been associated to Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and Mycoplasma hominis urogenital infections. However, evidence from large studies assessing their prevalence and putative associations in patients with infertility is still scarce. The study design was a cross-sectional study including 5464 patients with a recent diagnosis of couple’s primary infertility and 404 healthy control individuals from Cordoba, Argentina. Overall, the prevalence of C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis urogenital infection was significantly higher in patients than in control individuals (5.3%, 22.8% and 7.4% vs. 2.0%, 17.8% and 1.7%, respectively). C. trachomatis and M. hominis infections were significantly more prevalent in male patients whereas Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infections were more prevalent in female patients. Of clinical importance, C. trachomatis and Ureaplasma spp. infections were significantly higher in patients younger than 25 years. Moreover, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infections were associated to each other in either female or male patients being reciprocal risk factors of their co-infection. Our data revealed that C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis are prevalent uropathogens in patients with couple’s primary infertility. These results highlight the importance of including the screening of urogenital infections in the diagnostic workup of infertility.

Subject terms: Urogenital diseases, Bacterial infection, Infertility, Clinical microbiology

Introduction

Urogenital infections are known causes of infertility1. Currently, infertility affects 15–20% of reproductive-aged couples worldwide and women and men equally contribute to infertility cases1,2. Sexually transmitted infections can impair fertility by different mechanisms: by directly damaging organs and gametes and/or, indirectly, by the induced inflammation and associated tissue damage, scarring and obstruction1,3. Moreover, infection-induced genital inflammation may alter the normal immunomodulation process that naturally occurs in the female genital tract after mating to facilitate fertilization, embryo implantation and promote embryo growth for a successful pregnancy4. Besides being the most frequent sexually transmitted bacterial infection worldwide, Chlamydia trachomatis is a common infection associated to infertility5. In women, C. trachomatis is a known cause of different urogenital pathologies such as acute urethritis, cervicitis and salpingitis that may lead to severe reproductive complications including pelvic inflammatory disease, chronic pelvic pain, ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage and tubal infertility6,7. In men, C. trachomatis is considered the most common agent of non-gonococcal urethritis and may cause epididymitis-orchitis, prostatitis, sperm tract obstructions and alterations in sperm quality8,9. On the other hand, Mycoplasma hominis, and Ureaplasma urealyticum and Ureaplasma parvum (the latter being the only two Ureaplasma spp. associated to humans) have also been recognized as sexually transmitted infections that could impair human fertility1,10. Although they are known to colonize the female and male reproductive tracts as commensals, cumulative growing evidence has shown they are emerging sexually transmitted opportunistic pathogens able to cause asymptomatic chronic disorders affecting female and male fertility10–16. In men, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis are causes of non-gonococcal urethritis contaminating semen during ejaculation. Moreover, Ureaplasma spp. have been proposed to cause prostatitis, epididymitis and infertility1,10. In addition, reported data have shown that both Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis could impair sperm quality10,12,17,18. In women, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis may cause different pathologies including acute urethritis, bacterial vaginosis, pelvic inflammatory disease and tubal infertility15,19,20. Moreover, the asymptomatic infection by mycoplasmas or ureaplasmas could induce pro-inflammatory immune responses in the endometrium that may impair pregnancy outcomes2,9,15,21.

The detection rates of C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis in the urogenital tract form infertile women and men has shown striking variations across regions and countries and in different groups when individuals were classified according to age, ethnicity and socioeconomic status5,22–24. In that regard, a growing number of studies have been reported during the last decade. However, compelling available data from large cross-sectional studies is scarce22–24. Moreover, reported data about the association of these infections in either infertile women or men is limited22–24. Since these infections may play a significant role in the etiology of infertility, we herein conducted a large observational investigation into urogenital C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infections in women and men seeking care for couple’s primary infertility. Moreover, we analyzed the associations among infections and with demographic parameters such as patient sex and age.

Results

Prevalence of C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis urogenital infection in patients with couple’s primary infertility

A total of 5164 patients (1554 women and 3610 men) with a recent diagnosis of couple’s primary infertility undergoing initial infertility evaluation and 404 control individuals (64 women and 340 men) were enrolled in the study. The overall prevalence of urogenital C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infection was significantly higher in patients than in control individuals (5.3%, 22.8% and 7.4% vs. 2.0%, 17.8% and 1.7%, respectively, Table 1). In females, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infections were significantly more prevalent in patients than in controls (31.1% and 12.1% vs. 14.1% and 1.6%, respectively) whereas in males C. trachomatis and M. hominis infections were significantly more prevalent in patients than in controls (5.8% and 5.3% versus 1.8% and 1.8%, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of urogenital infections in patients with primary couple's infertility and control individuals.

| Total | Women | Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Controls | P | Patients | Controls | p | Patients | Controls | p | |

| Chlamydia trachomatis (%) | 5.3 | 2.0 | 0.0032 | 4.3 | 3.1 | 0.6453 | 5.8 | 1.8 | 0.0019 |

| Ureaplasma spp. (%) | 22.8 | 17.8 | 0.0215 | 31.1 | 14.1 | 0.0036 | 19.2 | 18.5 | 0.7005 |

| Mycoplasma hominis (%) | 7.4 | 1.7 | < 0.0001 | 12.1 | 1.6 | 0.0087 | 5.3 | 1.8 | 0.0041 |

Chi-square test. A *p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Bold p numbers mean those which are statistically significant (<0.05).

Demographic parameters associated to C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infection in patients with couple’s primary infertility

When analyzing the prevalence of infections within the patient population, it was found that C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infections were significantly associated with patient sex and age (Table 2). In fact, univariate regression analysis revealed that C. trachomatis infection was more likely to be detected in male than in female patients with an odds ratio of 1.36 (95% CI: 1.02–1.80, p = 0.034) (Table 2). Moreover, a significant association was particularly found between C. trachomatis infection and male patients younger than 25 years (OR: 2.51, 95% CI: 1.40–4.48, p = 0.002, Table 2) indicating that men, and especially those younger than 25 years, are at higher risk of infection than women (Table 2). Multivariate analysis further confirmed these associations (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 2.

Prevalence of infections in patients with couple’s primary infertility according to sex and age.

| Variables | Patients | C. trachomatis infection | Ureaplasma spp. infection | M. hominis infection | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n (prevalence) | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P | n (prevalence) | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p | n (prevalence) | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p | |

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Women | 1554 | 67 (4.3%) | 1.00 (ref.) | 484 (31.1%) | 1.00 (ref.) | 188 (12.1%) | 1.00 (ref.) | ||||||

| Men | 3610 | 208 (5.8%) | 1.36 | 1.02–1.80 | 0.034 * | 692 (19.2%) | 0.52 | 0.46–0.60 | < 0.001 * | 192 (5.3%) | 0.41 | 0.33–0.50 | < 0.001* |

| Age (y.o.) | |||||||||||||

| Women | |||||||||||||

| > 40 | 355 | 17 (4.8%) | 1.00 (ref.) | 107 (30.1%) | 1.00 (ref.) | 43 (12.1%) | 1.00 (ref.) | ||||||

| 40–25 | 1130 | 47 (4.2%) | 0.94 | 0.50–1.78 | 0.847 | 341 (30.2%) | 0.88 | 0.66–1.17 | 0.372 | 135 (11.9%) | 0.80 | 0.55–1.19 | 0.275 |

| < 25 | 69 | 3 (4.3%) | 0.96 | 0.26–3.50 | 0.949 | 36 (52.2%) | 2.27 | 1.33–3.89 | 0.003* | 10 (14.5%) | 1.04 | 0.49–2.22 | 0.910 |

| Men | |||||||||||||

| > 40 | 1356 | 88 (6.5%) | 1.00 (ref.) | 233 (17.2%) | 1.00 (ref.) | 72 (5.3%) | 1.00 (ref.) | ||||||

| 40—25 | 2161 | 106 (4.9%) | 0.71 | 0.52–0.95 | 0.021* | 433 (20.0%) | 1.26 | 1.04–1.51 | 0.016* | 16 (5.4%) | 1.03 | 0.75–1.41 | 0.863 |

| < 25 | 93 | 14 (15.1%) | 2.51 | 1.40–4.48 | 0.002* | 26 (28.0%) | 1.66 | 1.04–2.66 | 0.034* | 4 (4.3%) | 0.72 | 0.26–2.02 | 0.532 |

Univariate analysis. 95%CI: 95% confident interval. A *p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Bold p numbers mean those which are statistically significant (<0.05).

On the contrary, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infections were associated to female patients, since male patients were less likely at risk of Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infection than females with odds ratios of 0.52 (95% CI: 0.46–0.60, p < 0.001, Table 2) and 0.41 (95% CI: 0.33–0.50, p < 0.001, Table 2), respectively. In addition, it was found that Ureaplasma spp. was more prevalent in patients younger than 25 years, either in women or men (OR: 2.27, 95% CI: 1.33–3.89, p = 0.003, and OR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.04–2.66, p = 0.034, respectively; Table 2). Multivariate analysis further confirmed these data (Supplementary Table S1).

These results indicate that C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis urogenital infections are associated with patient sex and age. In fact, patients younger than 25 years at the highest risk of C. trachomatis and Ureaplasma spp. infection. Moreover, our data show that male patients are at higher risk of C. trachomatis infection and, conversely, female patients are at higher risk of Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infection.

Associations among C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis urogenital infections in patients with couple’s primary infertility

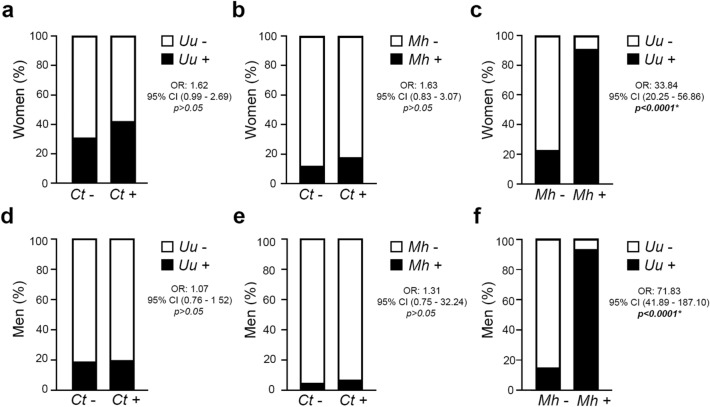

When assessing the co-infection between C. trachomatis and Ureaplasma spp. within the patient population, no significant association was found in either women (OR: 1.62, 95% CI: 0.99–2.69, p > 0.05) or men (OR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.76–1.52, p > 0.05) (Fig. 1a, d). In fact, a similar prevalence of Ureaplasma spp. was found in C. trachomatis infected (41.8%, 28/67) and C. trachomatis non-infected (30.7%, 456/1487) female patients (Fig. 1a, Table 3). In addition, a comparable prevalence of Ureaplasma spp. were found in C. trachomatis infected (20.2%, 42/208) and C. trachomatis non-infected (19.1%, 650/3402) male patients (Fig. 1d, Table 3).

Figure 1.

C. trachomatis (Ct), Ureaplasma spp. (Uu) and M. hominis (Mh) co-infections in patients with couple’s primary infertility. Frequency of positive Uu infection in Ct-infected (Ct+) or Ct-non infected (Ct−) female (a) or male (d) patients. Frequency of positive Mh infection in Ct-infected (Ct+) or Ct-non infected (Ct−) female (b) or male (e) patients. Frequency of positive Uu infection in Mh-infected (Mh+) or Mh-non infected (Mh−) female (c) or male (f) patients. Data are shown as frequency. Chi square test were assessed and odds ratio with 95% confident interval (OR, 95% CI) calculated. A *p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 3.

C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis co-infections in patients with couple’s primary infertility.

| C. trachomatis | M. hominis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | |

| (n = 67) | (n = 1487) | (n = 208) | (n = 3402) | (n = 188) | (n = 1366) | (n = 192) | (n = 3418) | |

| Ureaplasma spp. | ||||||||

| Positive n (%) | 28 (41.8%) | 456 (30.7%) | 42 (20.2%) | 650 (19.1%) | 171 (90.9%) * | 313 (22.9%) | 178 (92.7%) * | 514 (15.0%) |

| Negative n (%) | 39 (58.2%) | 1031 (69.3%) | 166 (79.8%) | 2752 (80.9%) | 17 (9.1%) | 1053 (77.1%) | 14 (7.3%) | 2904 (85.0%) |

| M. hominis | ||||||||

| Positive n (%) | 12 (17.9%) | 176 (11.8%) | 14 (6.7%) | 178 (5.2%) | – | – | - | - |

| Negative n (%) | 55 (82.1%) | 1311 (88.2%) | 194 (93.3%) | 3224 (94.8%) | – | – | - | - |

Univariate analysis. 95%CI: 95% confident interval. A *p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Bold p numbers mean those which are statistically significant (< 0.05).

Likewise, there was no significant association between C. trachomatis and M. hominis infections in either female patients (OR: 1.63, 95% CI: 0.83–3.07, p > 0.05) or male patients (OR: 1.31, 95% CI: 0.75–32.24, p > 0.05) (Fig. 1b, e). From the 67 female patients infected with C. trachomatis, 12 were positive for M. hominis (17.9%), whereas 176 out of the 1487 C. trachomatis-negative female patients were positive for M. hominis (11.8%) (Fig. 1b, Table 3). Also, a comparable prevalence of M. hominis was found in either C. trachomatis infected (6.7%, 14/208) or C. trachomatis non-infected (5.2%, 178/3402) male patients (Fig. 1e, Table 3).

Interestingly, a significant association between M. hominis and Ureaplasma spp. infection was found in female patients (OR: 33.84, 95% CI: 20.25–56.86, p < 0.0001) as well as in male patients (OR: 71.83, 95% CI: 41.89–187.10, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1c, Table 3). As detailed in Table 3, from the 188 female patients positive for M. hominis, 171 (91.0%) were positive for Ureaplasma spp. Similarly, a significantly increased prevalence of Ureaplasma spp. (92.7%) was found in M. hominis positive male patients (Fig. 1f). In fact, from the 192 male patients positive for M. hominis detection, 178 (92.7%) were positive for Ureaplasma spp. (Table 3). Multivariate regression analysis further confirmed these tight associations, indicating that Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis act as mutual risk factors of infection in either female or male patients (Supplementary Table S1).

Noteworthy, only 2.0% of infected female patients (11 out of 539) and 1.5% of infected male patients (13 out of 871) were co-infected with the three uropathogens analyzed (Supplementary Figure S1).

Discussion

Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis are amongst the most frequent sexually transmitted bacterial infections. Moreover, they have been associated to infertility in either females or males1–3,10,11,23. Therefore, compelling data about the prevalence of urogenital C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infection and their possible associations in partners of infertile couples is of utmost importance. It has been shown that the prevalence of urogenital C. trachomatis infection in infertile men and women varies considerable across nations and regions and according to the subject population under study25,26. Besides, although a growing number of studies about the prevalence of urogenital Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infections in infertile patients have been reported during the last decade, compelling available data from large cross-sectional studies is still scarce22–24. Thus, we herein conducted a large observational investigation into urogenital C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infections in women and men with couple’s primary infertility undergoing initial infertility evaluation. Our data revealed a significantly higher overall prevalence of C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infection in patients with respect to control individuals, being C. trachomatis and M. hominis significantly more prevalent in male patients than in control men and Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis significantly more prevalent in female patients than in control women. When analyzing the prevalence of infections within the patient population, univariate and multivariate regression analyses revealed that C. trachomatis infection was significantly more prevalent in males whereas Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infections were significantly more prevalent in females. The higher prevalence of C. trachomatis urogenital infection we found in male patients with respect to females could be due to the fact that urogenital infections in men are much more frequently asymptomatic than in women8. Besides, our results are in line with recently reported data showing higher prevalence of M. hominis and Ureaplasma spp. urogenital infections in infertile patients, especially in women18,27–29. Furthermore, our results also showed that C. trachomatis and Ureaplasma spp. infections were significantly more prevalent in young patients, particularly in those younger than 25, indicating that age as a risk factor and in agreement with previously reported data30,31. In fact, it is known that sexually transmitted infections are directly related to sexual experience, having young people more frequent sexual intercourses, less consistency of condom use and one or multiple sexual partners30,31. On the other hand, when assessing co-infections, only 2.0% of female patients and 1.5% of male patients were co-infected with the three uropathogens analyzed.

Our results support previously reported data. In a large observational study, Chen et al. found a prevalence of C. trachomatis infection of 3.5% in a population of 666 women seeking care for assisted reproduction in China, being significantly highest in patients younger than 25 years32. Moreover, Piscopo et al. reported a prevalence of C. trachomatis infection of 3.7% in women with tubal infertility in Brazil28. Besides and similar to our data, a prevalence of C. trachomatis infection of 4.3% in infertile men from Jordan has been reported33. Moreover, our results are in line with reported data by Sleha et al., who found a prevalence of U. urealyticum and M. hominis urogenital infection of 39.6% and 8.1%, respectively, in Czech women undergoing an initial infertility evaluation34. Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis showed a significant association between M. hominis and U. urealyticum infections and female infertility29. In addition, Gdoura et al. found a prevalence of U. urealyticum and M. hominis of 15.4% and 9.6% in male partners from infertile couples from Tunisia35. Similar data were also reported in infertile men from China36.

However, significantly different prevalence rates of urogenital C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. or M. hominis infection in infertile women or men have been reported in other studies. In comparison with our data, a much lower prevalence of Ureaplasma spp. infection was described in male partners of infertile couples from Italy37. Similarly, Boeri et al. recently reported lower prevalences of C. trachomatis and M. hominis infection in Italian men with primary infertility38. Moreover, in a study conducted in Spain, Veiga et al. found lower rates of C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infection in male partners of infertile couples than ours (0.9%, 15.1% and 0.9%, respectively)39. In addition, considerably lower prevalence rates of C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infection were reported in female partners of infertile couples from the USA40. Several factors could underlie these differences such as disparities in population under study (geographical location, age, ethnicity, religion, socio-economic status, access to medical care, etc.) or study design [prospective versus retrospective, patient population size, methods used for infection diagnosis (culture, PCR, etc., qualitative versus quantitative), etc.]. However, our results are in line with cumulative reported data and supported by the large patient population analyzed, including 5164 infertile individuals (1554 women and 3610 men).

Besides, our data revealed that C. trachomatis infection was not associated to either Ureaplasma spp. or M. hominis in female as well as in male patients. Conversely, and supporting recently reported data41–43, Ureaplasma spp. or M. hominis were significantly associated to each other in either female or male patients, indicating that Ureaplasma spp. or M. hominis urogenital infection increased the risk of M. hominis or Ureaplasma spp. co-infection. This tight infection association could be due to shared infection routes and/or pathophysiologic mechanisms1,11.

To our knowledge, this is the first cross-sectional study to investigate the prevalence and association of C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis in patients with couple’s primary infertility from Argentina. Being one of the few cross-sectional study performed in Latin American countries22,24 and the large number of patients analyzed are the main strengths of our study. However, our study has some limitations such as the relatively smaller number of controls included, especially women. Moreover, we did not have the information of the partner couple of every female or male patient enrolled, which could have provided important information about infection concordance.

In conclusion, our results indicate that urogenital C. trachomatis, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infections are prevalent in patients with couple’s primary infertility. C. trachomatis and M. hominis infections were significantly more prevalent in male patients whereas Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis infections were more prevalent in female patients. Of clinical importance, C. trachomatis and Ureaplasma spp. infections were more prevalent in young patients, especially in those younger than 25 years. Moreover, Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis showed to be reciprocal risk factors of their co-infection in either female or male patients. Overall, these results point out the importance to include the microbiological screening of urogenital infections in the diagnostic workup for infertility. Moreover, they highlight the need to reinforce preventive strategies at the primary healthcare level. Increasing awareness among people and health care practitioners are efficient approaches for the prevention of infection transmission. Future research is needed to unveil the true impacts of these uropathogens and the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, which would allow the identification of proper and efficient treatments to more effectively reduce the burden of infertility.

Methods

Study design, patients and samples

This cross-sectional study was performed on a total cohort of 5164 consecutive Argentinian patients (1554 females and 3610 males) with a recent diagnosis of couple’s primary infertility undergoing initial infertility evaluation and in 404 healthy control individuals (64 women and 340 men) assessed at a joint Academic, Urology and Reproduction Health Center between January 2015 and November 2019. Expert, infertility-trained gynecologists or uro-andrologists comprehensively evaluated patients and primary infertility was diagnosed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, i.e. when a couple was unable to conceive a pregnancy after at least 12 months of unprotected intercourse44. Patients did not have any signs or symptoms of genital tract infections (urethral or vaginal discharge, dysuria, urethral irritation, itching, genital lesions, and pelvic/abdominal pain). Control individuals were seemingly healthy women or men attending the center during the same study period to receive regular annual physical, gynecological and/or urological check-up without fertility-related complaints and clinically asymptomatic for any infection. Inclusion criteria for either patients or controls were female or male aged 18–60 years, and not taking antibiotics when sampling and during the last 3 weeks. Cervicovaginal-swab and semen samples were collected from female and male individuals, respectively. Well-trained and experienced operators collected different cervicovaginal swabs for the detection of C. trachomatis or Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis. Dacron swabs were inserted into the vagina up to the vault, rotated in the vaginal vault and vigorously scrubbed the mucous lining. The specimens were immediately transferred to tubes containing specific transport media and processed for analysis. Semen samples were collected by masturbation after 2–7 days of sexual abstinence and processed within 1 h of collection.

Ethical approval

The study was carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) standards and the Argentinian legislation for protection of personal data (Law 25326). The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee from the Hospital Nacional de Clinicas, Universidad Nacional de Cordoba (RePIS #3512). All patients and controls provided a signed written informed consent form agreeing to share their own anonymous information.

DNA extraction and C. trachomatis detection

Total DNA was extracted from vaginal or semen samples and C. trachomatis infection detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the C. trachomatis 330/740 IC PCR kit (Sacace Biotechnologies Srl, Como, Italy) and following the manufacturer’s instructions. Analyses were performed within 4 h of sample collection.

Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma spp. infection assessment

Mycoplasma hominis or Ureaplasma spp. detection and enumeration were assessed by culture using the commercially available Complement Mycofast RevolutioN assay (ELITech MICROBIO, Signes, France) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, vaginal swabs or semen samples were inoculated in UMMt transport medium that contains preservatives and selective agents to inhibit the growth of contaminating flora. This medium was then dispensed into test wells, covered with two drops of mineral oil, sealed and incubated at 37 °C ± 1 °C for 24–48 h and observed for color changes. According to the kit specifications and as previously indicated10,45–47, a positive result was recorded when orange or red color changes were observed, indicating the presence of M. hominis and/or Ureaplasma spp., respectively, at a load of each microorganism ≥ 104 CFU/ml.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistical software, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Infection prevalences between patient and control groups were compared using Chi-Square test. Demographic characteristics (age, sex) and co-infections between infected and non-infected patients were compared using the chi-square test and the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses for all variables were performed to determine associations or risk factors for infections. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

R.D.M., G.M., and R.M. participated in the conception and design of the study. G.M., D.A.P., A.D.T., C.O. and R.I.M. participated in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. R.D.M. wrote the manuscript text and D.A.P. prepared the figure and tables. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version before submission.

Funding

Secretaría de Ciencia y Tecnología. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (SECyT-UNC-A). Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (PICT 2019-2451). Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (PIP 0100652).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-93318-1.

References

- 1.Gimenes F, et al. Male infertility: A public health issue caused by sexually transmitted pathogens. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2014;11:672–687. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vander Borght M, Wyns C. Fertility and infertility: Definition and epidemiology. Clin. Biochem. 2018;62:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hart RJ. Physiological aspects of female fertility: Role of the environment, modern lifestyle, and genetics. Physiol. Rev. 2016;96:873–909. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schjenken JE, Robertson SA. The female response to seminal fluid. Physiol. Rev. 2020;100:1077–1117. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang W, et al. Pregnancy and fertility-related adverse outcomes associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infection: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm. Infect. 2019 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2019-053999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunham RC, Rappuoli R. Chlamydia trachomatis control requires a vaccine. Vaccine. 2013;31:1892–1897. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paavonen J. Chlamydia trachomatis infections of the female genital tract: State of the art. Ann. Med. 2012;44:18–28. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.546365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackern-Oberti JP, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis infection of the male genital tract: An update. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2013;100:37–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farsimadan M, Motamedifar M. Bacterial infection of the male reproductive system causing infertility. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2020;142:103183. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2020.103183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beeton ML, Payne MS, Jones L. The role of Ureaplasma spp. in the development of nongonococcal urethritis and infertility among men. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019 doi: 10.1128/CMR.00137-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stojanov M, Baud D, Greub G, Vulliemoz N. Male infertility: The intracellular bacterial hypothesis. New Microbes New Infect. 2018;26:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2018.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: From chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011;24:498–514. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capoccia R, Greub G, Baud D. Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2013;26:231–240. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328360db58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volgmann T, Ohlinger R, Panzig B. Ureaplasma urealyticum-harmless commensal or underestimated enemy of human reproduction? A review. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2005;273:133–139. doi: 10.1007/s00404-005-0030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keane FE, Thomas BJ, Gilroy CB, Renton A, Taylor-Robinson D. The association of Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma genitalium with bacterial vaginosis: Observations on heterosexual women and their male partners. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2000;11:356–360. doi: 10.1258/0956462001916056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manhart LE, Holmes KK, Hughes JP, Houston LS, Totten PA. Mycoplasma genitalium among young adults in the United States: An emerging sexually transmitted infection. Am. J. Public Health. 2007;97:1118–1125. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang C, et al. Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis infections and semen quality in 19,098 infertile men in China. World J. Urol. 2016;34:1039–1044. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1724-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmadi MH, Mirsalehian A, Sadighi Gilani MA, Bahador A, Talebi M. Asymptomatic infection with Mycoplasma hominis negatively affects semen parameters and leads to male infertility as confirmed by improved semen parameters after antibiotic treatment. Urology. 2017;100:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen JS, Svenstrup H, Stacey CM. Difficulties experienced in defining the microbial cause of pelvic inflammatory disease. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2012;23:18–24. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2011.011066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor-Robinson D. Infections due to species of Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma: An update. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1996;23:671–682. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwak DW, Hwang HS, Kwon JY, Park YW, Kim YH. Co-infection with vaginal Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis increases adverse pregnancy outcomes in patients with preterm labor or preterm premature rupture of membranes. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 2014;27:333–337. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.818124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farahani L, et al. The semen microbiome and its impact on sperm function and male fertility: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Andrology. 2020 doi: 10.1111/andr.12886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroon SJ, Ravel J, Huston WM. Cervicovaginal microbiota, women's health, and reproductive outcomes. Fertil. Steril. 2018;110:327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsevat DG, Wiesenfeld HC, Parks C, Peipert JF. Sexually transmitted diseases and infertility. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;216:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redgrove KA, McLaughlin EA. The role of the immune response in Chlamydia trachomatis infection of the male genital tract: A double-edged sword. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:534. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang W, et al. Pregnancy and fertility-related adverse outcomes associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infection: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm. Infect. 2020;96:322–329. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2019-053999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moridi K, et al. Epidemiology of genital infections caused by Mycoplasma hominis, M. genitalium and Ureaplasma urealyticum in Iran; a systematic review and meta-analysis study (2000–2019) BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1020. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08962-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piscopo RC, et al. Increased prevalence of endocervical Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma colonization in infertile women with tubal factor. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2020;24:152–157. doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20190078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tantengco OAG, de Castro Silva M, Velayo CL. The role of genital mycoplasma infection in female infertility: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/aji.13390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aung ET, et al. International travel as risk factor for Chlamydia trachomatis infections among young heterosexuals attending a sexual health clinic in Melbourne, Australia, 2007 to 2017. Euro Surveill. 2019 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.44.1900219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.CDC . Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2018. CDC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen H, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis and human papillomavirus infection in women from southern Hunan Province in China: A large observational study. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:827. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abusarah EA, Awwad ZM, Charvalos E, Shehabi AA. Molecular detection of potential sexually transmitted pathogens in semen and urine specimens of infertile and fertile males. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013;77:283–286. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sleha R, et al. Prevalence of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in women undergoing an initial infertility evaluation. Epidemiol. Mikrobiol. Imunol. 2016;65:232–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gdoura R, et al. Assessment of Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Ureaplasma parvum, Mycoplasma hominis, and Mycoplasma genitalium in semen and first void urine specimens of asymptomatic male partners of infertile couples. J. Androl. 2008;29:198–206. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.107.003566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song T, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Han Y, Huang J. Detection of Ureaplasma spp. serovars in genital tract of infertile males. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2019;33:e22865. doi: 10.1002/jcla.22865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moretti E, et al. The presence of bacteria species in semen and sperm quality. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2009;26:47–56. doi: 10.1007/s10815-008-9283-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boeri L, et al. Semen infections in men with primary infertility in the real-life setting. Fertil. Steril. 2020;113:1174–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veiga E, et al. Prevalence of genital Mycoplasma and response to eradication treatment in patients undergoing assisted reproductive techniques. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2019;32:327–332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imudia AN, Detti L, Puscheck EE, Yelian FD, Diamond MP. The prevalence of Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis, Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections, and the rubella status of patients undergoing an initial infertility evaluation. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2008;25:43–46. doi: 10.1007/s10815-007-9192-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee JY, Yang JS. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma species in nonpregnant female patients in South Korea indicate an increasing trend of pristinamycin-resistant isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01065-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee MY, Kim MH, Lee WI, Kang SY, Jeon YL. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in pregnant women. Yonsei Med. J. 2016;57:1271–1275. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.5.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buzo BF, et al. Association between Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma airway positivity, ammonia levels, and outcomes post-lung transplantation: A prospective surveillance study. Am. J. Transplant. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ajt.16394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.WHO. World Health Organization Web Chapter on Couple’s Infertility. URL: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/infertility/definitions.

- 45.Frolund M, et al. Urethritis-associated pathogens in urine from men with non-gonococcal urethritis: A case-control study. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2016;96:689–694. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimada Y, et al. Bacterial loads of Ureaplasma urealyticum contribute to development of urethritis in men. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2014;25:294–298. doi: 10.1177/0956462413504556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deguchi T, et al. Bacterial loads of Ureaplasma parvum contribute to the development of inflammatory responses in the male urethra. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2015;26:1035–1039. doi: 10.1177/0956462414565796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.