Abstract

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a biological process through which epithelial cells transdifferentiate into mesenchymal cells, is involved in several pathological events, such as cancer progression and organ fibrosis. So far, we have found that methotrexate (MTX), an anticancer drug, induced EMT in the human A549 alveolar adenocarcinoma cell line. However, the relationship between EMT and the cytotoxicity induced by MTX remains unclear. In this study, we compared the processes of MTX-induced EMT and apoptosis in A549 cells. Q-VD-Oph, a caspase inhibitor, suppressed MTX-induced apoptosis, but not the increase in mRNA expression of α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), a representative EMT marker. In addition, SB431542, an EMT inhibitor, did not inhibit MTX-induced apoptosis. By using isolated clonal cells from wild-type A549 cells, the induction of EMT and apoptosis by MTX in each clone was analyzed, and no significant correlation was observed between the MTX-induced increase in α-SMA mRNA expression and the proportion of cells undergoing apoptosis. Furthermore, the increase in the mRNA expression of α-SMA was well correlated with cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A, a cell cycle arrest marker, but not with BCL-2 binding component 3 and Fas cell surface death receptor, which are both pro-apoptotic factors, indicating that the MTX-induced EMT may be related to cell cycle arrest, but not to apoptosis. These findings suggested that different mechanisms were involved in the MTX-induced EMT and apoptosis.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Methotrexate, p21, α-Smooth muscle actin

Introduction

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a cellular process that transiently places epithelial cells into a mesenchymal cell type. During EMT, epithelial cells lose polarity and cobblestone morphology, but acquire a spindle-shaped morphology with the upregulation of mesenchymal markers, including fibronectin, α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), and vimentin [1]. In general, there are three types of EMT, depending on to the biological context in which they occur [2]. In brief, type I EMT is observed during embryonic development, type II EMT occurs during wound healing and tissue regeneration, and type III EMT occurs during cancer progression, such as metastasis and invasion. As some serious pathological problems, such as organ fibrosis and cancer progression, are known to be associated with EMT [3–5], suppression of EMT is believed to be a potential therapeutic approach for EMT-related diseases. Multiple therapeutic modalities, such as small-molecule compounds, neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, and antisense oligonucleotides, have been developed to inhibit the activity of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, a representative EMT inducer [6]. However, there are currently no clinically availably therapeutic agents for the treatment of organ fibrosis and cancer progression associated with EMT.

Several reports have suggested the EMT-inducing effects of certain anticancer drugs [7–9], on the assumption that EMT-related diseases would be caused by the clinical use of those drugs. Indeed, it has been reported that several anticancer drugs led to the development of lung injury at a high frequency in the drugs with pulmonary toxicity [10]. We also found that bleomycin (BLM) and methotrexate (MTX) induced EMT-like phenotypical changes in cultured alveolar epithelial cell lines [11]. However, we showed that SB431542, a specific inhibitor against the signaling pathway triggered by TGF-β1, did not completely suppress the MTX-induced EMT in A549 cells [9]. Thus, targets other than the TGF-β1 signaling pathway may be associated with the drug-induced EMT, and the clarification of these factors may contribute to the establishment of an effective preventive approach against drug-induced EMT, and potentially EMT-related serious diseases.

In general, the cytotoxic effects of anticancer drugs on tumor cells are due to the induction of cell death and/or cell cycle arrest. Although we have demonstrated that cell cycle arrest was associated with the drug-induced EMT in A549 cells [12], the relationship between cell death and the drug-induced EMT has not been fully elucidated. Apoptosis, a known method of programmed cell death, is mostly observed in tumor cells as a result of the use of chemotherapeutic agents. Given that MTX is known to induce apoptosis in A549 cells [13], a comparison between the induction of cell death and the induction of EMT by MTX should contribute to novel discoveries concerning the specific mechanisms underlying the drug-induced EMT. Therefore, in this study, the relationship between apoptosis and the EMT induced by MTX was examined by using inhibitors against both events. On the other hand, we previously observed by flow cytometry that α-SMA protein expression levels were widely distributed among MTX-treated A549 cells [14], indicating that there would be EMT-positive or negative A549 cells in response to MTX treatment. Therefore, it should be interesting to clarify whether the different reactivity of the cells to MTX-induced EMT corresponds to the apoptosis ratio or not, which would help to further understand the relationship between EMT and apoptosis. Accordingly, using isolated clonal cells from A549 cells, alterations in the expression of the genes related to EMT and apoptosis during MTX treatment were also compared by bivariate analysis.

Materials and methods

Materials

MTX, propidium iodide (PI), and SB431542 (SB) were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan). Q-VD-Oph (QVD) was purchased from BioVision, Inc. (San Francisco, CA, USA). FITC-Annexin-V was purchased from Medical & Biological Laboratories Co., Ltd. (Nagoya, Japan). All other chemicals used in the present study were of the highest purity commercially available.

Cell culture and preparation of cloned cells

The human-derived alveolar adenocarcinoma cell line A549 was cultured as reported previously [9]. For the preparation of clonal cells, the cells were first seeded at a density of 20 cells/100-mM dish by the limiting dilution method [15]. Briefly, when colonies of cells were observed, a cloning cylinder was placed on each colony, and 50 µL 0.25% trypsin-1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-4Na was added into each cylinder. After the cells were detached, they were transferred to a 24-well plate by using a pipette tip and cultured in the same way as A549 cells.

Drug treatment

A549 and isolated cloned cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well in a 12-well plate for real-time PCR analysis or 5 × 105 cells/dish in a 60-mM dish for the apoptosis assay. After 24 h, the cells were treated with MTX (0.3 µM) in the absence or presence of QVD (30 µM) or SB (10 µM) for 72 h.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was prepared from drug-treated cells by using the Monarch Total RNA Miniprep Kit (New England Biolabs Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The reverse transcription of RNA into cDNA and real-time PCR analysis were performed as previously reported [9]. The following primer sequences were used: human α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), sense, 5ʹ-GCTGTTTTCCCATCCATTGT-3ʹ and antisense, 5ʹ-TTTGCTCTGTGCTTCGTCAC-3ʹ; human cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKN) 1A sense, 5ʹ-GTGGACCTGTCACTGTCTTG-3ʹ and antisense, 5ʹ-GGCGTTTGGAGTGGTAGAAA-3ʹ; human BCL-2 binding component (BBC) 3 sense, 5ʹ-GACGACCTCAACGCACAGTA-3ʹ and antisense, 5ʹ-CTAATTGGGCTCCATCTCGG-3ʹ; human Fas cell surface death receptor (FAS) sense, 5ʹ-AGTCAATGGGGATGAACCAG-3ʹ and antisense, 5ʹ-GTCCGGGTGCAGTTTATTTC-3ʹ; human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) sense, 5ʹ-ACGGGAAGCTTGTCATCAAT-3ʹ and antisense, 5ʹ-TGGACTCCACGACGTACTCA-3ʹ. The expression of mRNA was normalized to that of GAPDH mRNA, a housekeeping gene.

Apoptosis assay

After the drug treatment, the detached cells were counted, and the cell suspension was adjusted to 2 × 105 cells/mL. After centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min, the pellet was resuspended with 85 µL binding buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.4). Then, FITC-labeled Annexin-V (10 µL) and PI (5 µL) were added to the cell suspension and incubated for 15 min at approximately 23 °C. FITC and PI fluorescence were analyzed by using Guava easyCyte® (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX, USA).

Bivariate analysis

Spearman’s rank test was used for the evaluation of correlation between the mRNA expression of several genes and the apoptosis ratio in MTX-treated cloned cells.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed by using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Association of MTX-induced apoptosis with EMT in A549 cells

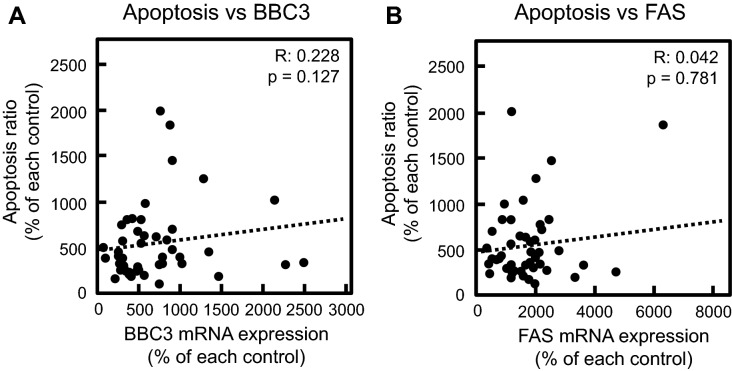

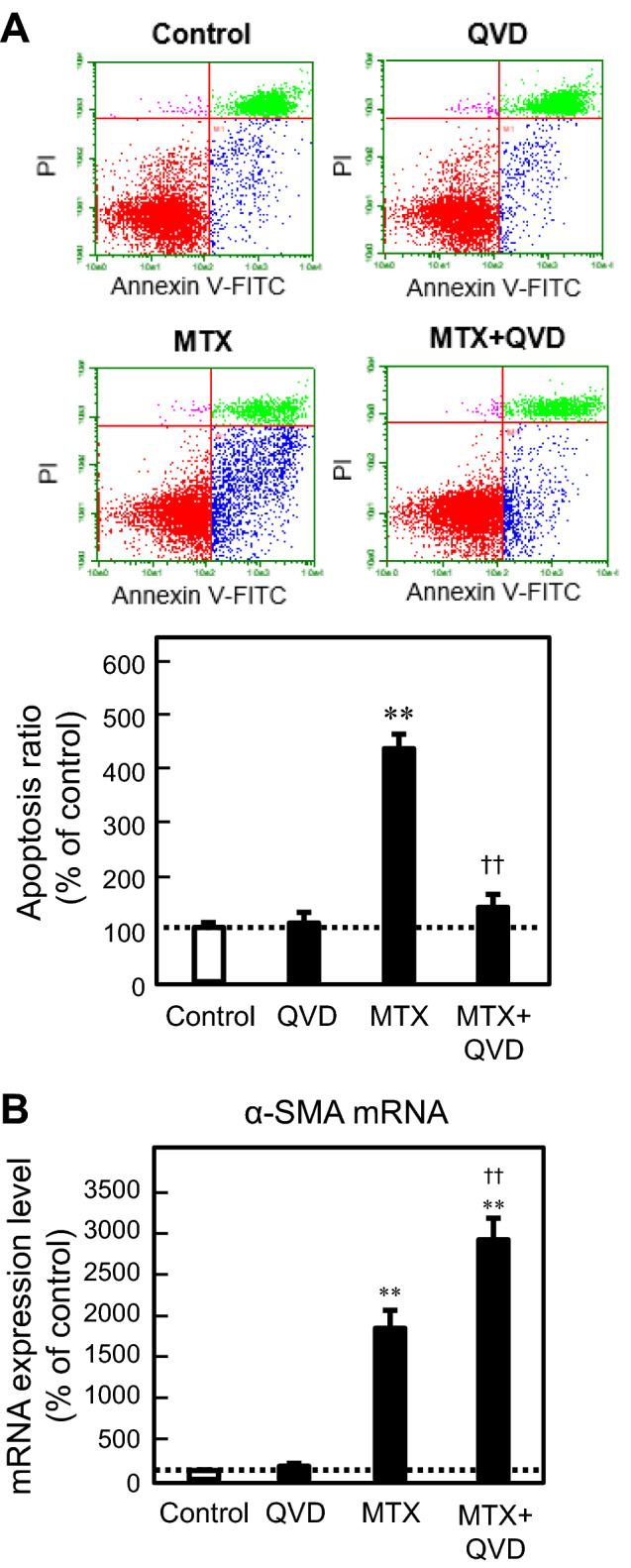

To clarify the association of MTX-induced apoptosis with EMT in A549 cells, the effects of inhibitors against apoptosis and EMT on both events induced by MTX were examined. QVD, a cell-permeable peptide inhibitor against caspase activity, clearly suppressed MTX-induced apoptosis in A549 cells, but did not ameliorate, and instead upregulated, the increase in mRNA expression of α-SMA, an EMT marker, induced by MTX (Fig. 1). In contrast, the effect of SB, a known inhibitor of EMT via suppression of the TGF-β signaling pathway, on MTX-induced apoptosis was examined. Notably, SB had no significant effect on MTX-induced apoptosis (Fig. 2). In addition, our previous report demonstrated that the MTX-induced EMT was inhibited by co-treatment with SB [9]. These findings suggested that the process of apoptosis would be different from that of EMT during MTX treatment in A549 cells.

Fig. 1.

Effect of Q-VD-Oph (QVD) on MTX-induced apoptosis and the MTX-induced EMT in A549 cells. The cells were treated with 0.3 µM MTX in the presence or absence of 30 µM QVD for 72 h. a The proportion of apoptotic cells (annexin V-positive, PI-negative) was detected and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in the “Materials and methods”. b The mRNA expression of α-SMA was analyzed by real-time PCR. Each value represents the mean ± SEM (n = 03). **p < 0.01; significantly different from each control. ☨☨p < 0.01; significantly different from MTX

Fig. 2.

Effect of SB431542 (SB) on MTX-induced apoptosis in A549 cells. The cells were treated with 0.3 µM MTX in the presence or absence of 10 µM SB for 72 h. The proportion of apoptotic cells (annexin V-positive, PI-negative) was detected and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in the “Materials and methods”. Each value represents the mean ± SEM (n = 03). **p < 0.01; significantly different from each control

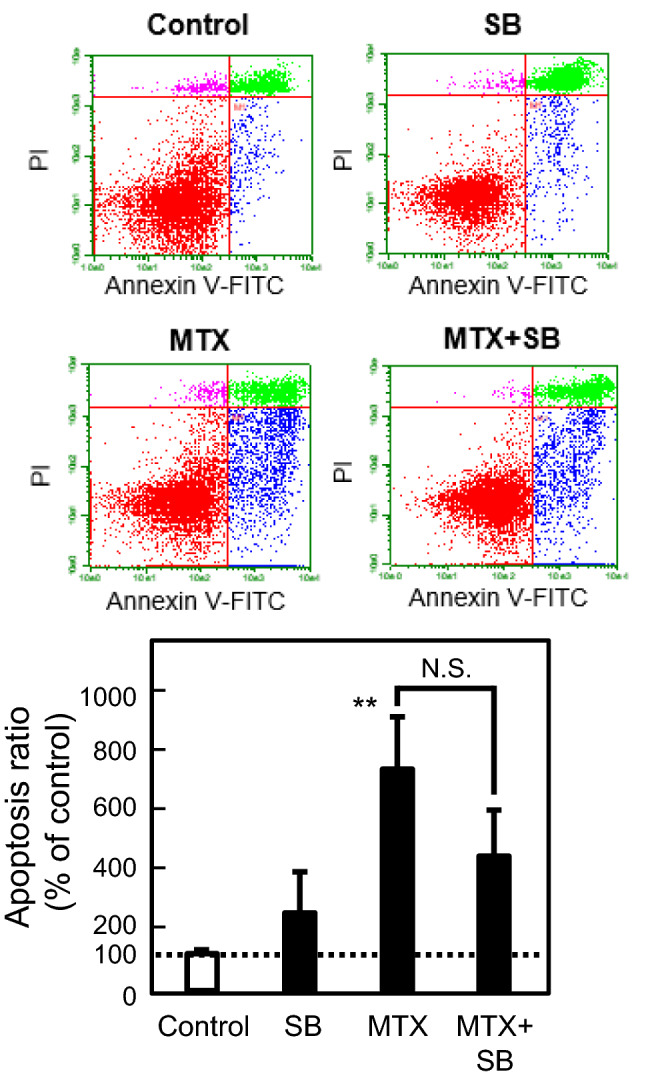

Correlation between MTX-induced apoptosis and EMT in cloned A549 cells

Cultured cell lines, including A549 cells, can be considered as a population of cells with different cellular phenotypes. Based on the heterogeneity of cells, we tried to establish cloned cells by the limiting dilution method, as reported previously [15], and compared the ratio of apoptosis and the increase in α-SMA mRNA expression induced by MTX in each clone. As shown in Fig. 3, there was no statistically significant correlation between MTX-induced apoptosis and EMT in A549 cells, which supported the results shown using inhibitors of apoptosis and EMT, as presented in Figs. 1 and 2.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between MTX-induced apoptosis and EMT. Cloned A549 cells obtained by the limited dilution method were treated with 0.3 µM MTX for 72 h. The proportion of apoptotic cells (annexin V-positive, PI-negative) in each clone was detected and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in the “Materials and methods”. The mRNA expression of α-SMA was analyzed by real-time PCR. Dots in the scatterplot show each clone. The R value represents Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient

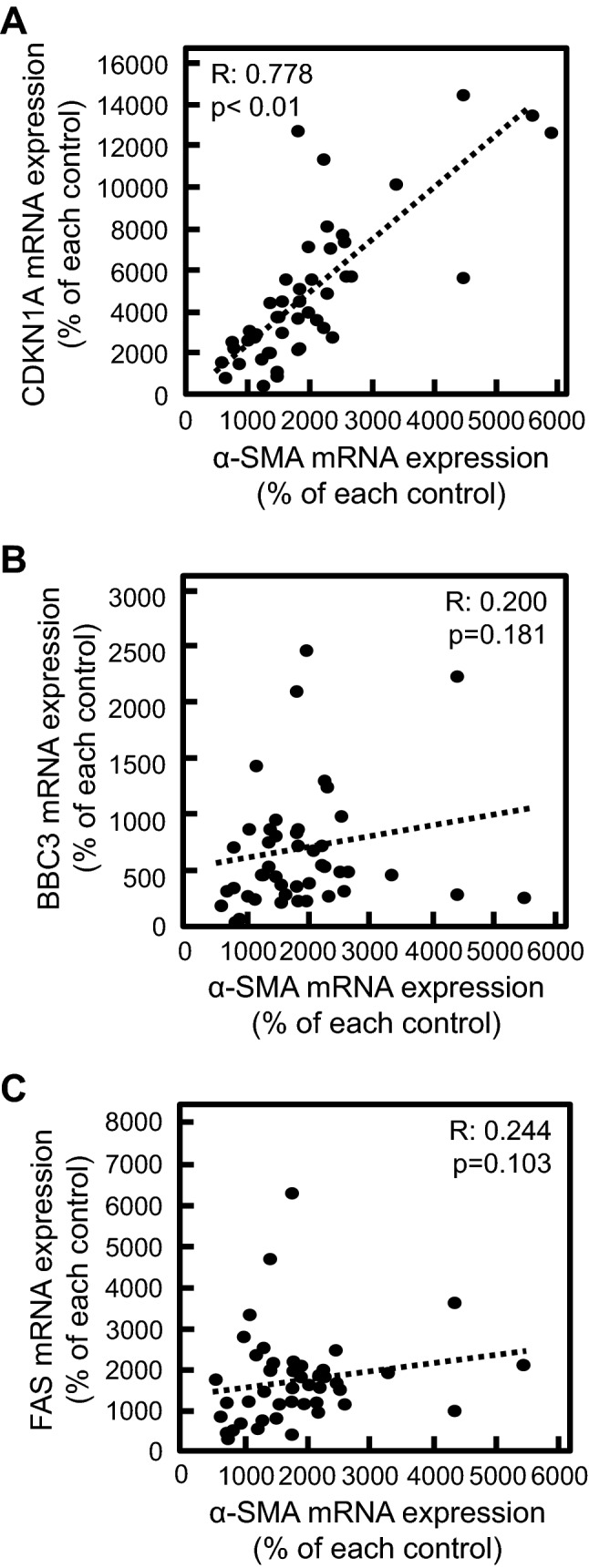

Role of p53-related factors in MTX-induced EMT

We previously reported that the MTX-induced EMT was associated with cell cycle arrest through the upregulation of CDKN1A encoding p21 under the transcriptional control of p53 [12]. Alternatively, the p53-mediated transcriptional regulation of BBC3 or FAS plays an important role in induction of apoptosis. Therefore, by using total RNA obtained from established cloned cells treated with or without MTX, we performed bivariate analysis focusing on the relationship between EMT and mRNA expression of CDKN1A, BBC3, and FAS in MTX-treated cloned cells. A significant positive correlation of the increase in the mRNA expression of α-SMA with that of CDKN1A was observed, whereas there was no correlation between α-SMA and apoptosis-related genes such as BBC3 and FAS (Fig. 4). These findings indicated that the p53-mediated pathway may be associated with EMT, but not apoptosis, in MTX-treated A549 cells.

Fig. 4.

Correlation between the MTX-induced EMT and p53-related gene expression. Cloned A549 cells obtained by limited dilution method were treated with 0.3 µM MTX for 72 h. The mRNA expression of α-SMA (a–c), CDKN1A (a), BBC3 (b), and FAS (c) was analyzed by real-time PCR. Dots in the scatterplot indicate each clone. The R value represents Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient

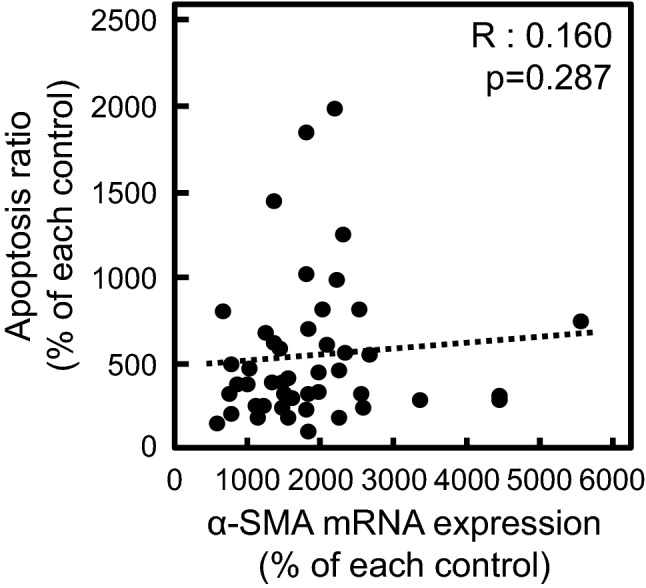

Role of p53-related factors in MTX-induced apoptosis

The association of MTX-induced apoptosis with FAS and BBC3 was also examined by bivariate analysis using total RNA from cloned A549 cells. Notably, there was no significant correlation in the changes in the proportion of cells undergoing apoptosis and the mRNA expression of BBC3 and FAS induced by MTX (Fig. 5), indicating that the p53 pathway may not be associated with MTX-induced apoptosis in A549 cells.

Fig. 5.

Correlation of MTX-induced apoptosis with mRNA expression level in the cloned cells. The cloned cells derived from A549 cells were treated without (control) or with MTX (0.3 µM) for 72 h. After that, the cells were used for measuring apoptosis ratio and mRNA expression levels of BBC3 (a) or FAS (b) as described in “Materials and methods”. Dots in the scatterplot mean each cloned cell. R value means spearman’s rank correlation coefficient

Discussion

Much evidence exists to show the EMT-inducing effects of chemotherapeutic agents. For example, we, and other research groups, demonstrated that BLM and MTX induced EMT in A549 cells via the TGF-β signaling pathway [7, 9]. Both drugs are currently used as cytotoxic agents against various tumors in clinical practice. Recently, there have been several reports to show that EMT contributes to resistance against chemotherapeutic drugs in several types of tumors, including lung tumors [16, 17]. Chemotherapeutic drugs may lead to drug resistance through induction of EMT. In addition, EMT-related diseases, such as pulmonary fibrosis, may be associated with the adverse drug reactions through the clinical use of chemotherapeutic drugs [10]. However, the relationship between chemotherapy drug-induced EMT and the cytotoxic effects has not been fully elucidated. In the present study, the association of the MTX-induced EMT with apoptotic properties in A549 cells was examined.

To evaluate the relationship between apoptosis and the EMT induced by MTX in A549 cells, small molecule inhibitors against apoptosis and EMT were used. A significant inhibitory effect of QVD, an inhibitor of apoptosis, on MTX-induced apoptosis in A549 cells was observed, whereas QVD did not suppress the MTX-induced increase in the mRNA expression of α-SMA, but rather increased it. The cells escaping MTX-induced apoptosis by the co-treatment with QVD would contribute to the increased mRNA expression of α-SMA. These results suggested that the regulation of α-SMA expression during MTX treatment may not be associated with the intracellular events related to MTX-induced apoptosis. However, SB, an EMT inhibitor, induced no significant effects on the apoptosis ratio altered by MTX, indicating that the mechanism underlying MTX-induced apoptosis may be different from the EMT process induced by MTX. Both findings strongly suggested the differential mechanism between the MTX-induced EMT and apoptosis in A549 cells.

Considering the fact that MTX induced both EMT and apoptosis in A549 cells, the cells may be regarded as a heterogenous population of cells in which EMT or apoptosis occurs in response to MTX treatment. By using the limited dilution method, we tried to obtain a cloned cell population showing only apoptosis or EMT following MTX treatment. However, both the upregulation of α-SMA mRNA expression and apoptosis were observed in all the cloned cells treated with MTX. In general, genetic alterations occurring during the culture and passage of cultured cells influence gene expression and, ultimately, cellular functions [18]. For example, it has been reported that genetic heterogeneity and wide variation in drug responses to several anticancer compounds were observed in 27 strains of MCF-7 breast cancer cells [19]. In contrast, a positive correlation between the mRNA expression of α-SMA and CDKN1A in MTX-treated cloned cells was observed in the present study. Therefore, our experimental approach may provide an effective comparison of the alterations of certain genes during drug treatment, though it should be noted that the property of each clone has not been fully characterized at this moment.

Bivariate analysis concerning MTX-induced EMT and apoptosis in the cloned cells supported our conclusion indicating that different mechanisms would be involved in these events, as evidenced by the low correlation coefficient. Furthermore, it is reported that TGF-β1 induces EMT and apoptosis at G2/M and S of the cell cycle phase, respectively [20], suggesting the involvement of different mechanisms in EMT and apoptosis induced by TGF-β1 treatment. However, it should be difficult to directly demonstrate no correlation between EMT and apoptosis induced by MTX, and further studies are needed to clarify each molecular mechanism underlying these events.

Recently, we demonstrated that the MTX-induced EMT was associated with cell cycle arrest by using several methods, including cell synchronization and a cell sorting technique [12]. In addition, a significant correlation in mRNA expression between α-SMA and CDKN1A, encoding p21, a known factor related to cell cycle arrest [21], was observed in MTX-treated cloned cells in the present study. p21 is a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor that suppresses cellular proliferation through the inhibition of CDK1/2 activity in the G1/S and G2/M phases of cell cycle [22]. In the case of the EGF-induced EMT in Caov-3 ovarian cancer cells, remarkable increases in p21 protein expression have been reported [23], indicating that p21 may play an important role in EMT induction stimulated by EMT inducers such as MTX and EGF. In contrast, it is also reported that p21 acts a factor that suppresses EMT [24–26]. Further studies are required to clarify the detailed contribution of p21 to the drug-induced EMT.

The p53 protein, a tumor suppressor protein, transcriptionally regulates various genes related to apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and senescence. As previously reported, we demonstrated that miR-34a directly contributed to the MTX-induced EMT in A549/ABCA3 cells via the activation of p53 [11], indicating that p53 is an important factor in the drug-induced EMT. Therefore, the mRNA expression of apoptosis-related genes under the transcriptional control of p53, such as BBC3 and FAS, and α-SMA was compared to evaluate the relationship between MTX-induced apoptosis and EMT. The present study showed that there was no positive correlation between BBC3/FAS and α-SMA mRNA expression, and that the proportion of MTX-induced apoptosis was not significantly correlated with alterations in the mRNA expression of BBC3 and FAS, leading to the hypothesis that MTX-mediated p53 regulation may contribute to the induction of EMT, but not apoptosis. In addition, it has been reported that the p53-p21 axis suppressed the mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET), which is defined as the reverse reaction to EMT [27], indicating that p53 may promote the MTX-induced EMT by inhibition of the MET process in A549 cells. In contrast, it is reported that the depletion of p53 enhances the EMT process in various cell lines [28–30]. Although it currently remains unclear whether p53 enhances or suppresses EMT, the p53-mediated transcriptional regulation of p21 may be associated with the MTX-induced EMT in A549 cells, as shown in the present study.

In general, apoptotic pathways can be divided into three categories; intrinsic, extrinsic, and membrane stress pathways [31]. BBC3 and FAS regulated by p53 are known to play an important role in intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis pathway, respectively. On the other hand, it is reported that caspase 3, but not p53, is the critical factor in MTX-induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells [32], which is comparable to the present study suggesting no correlation of p53 pathway with MTX-induced apoptosis. Therefore, upregulation of BBC3 and FAS may not be involved in MTX-induced apoptosis under our experimental conditions. In addition, membrane stress pathway is independent of p53 [33]. Ceramide synthase 6 is known to be involved in membrane stress apoptotic pathway, and is upregulated by MTX treatment in A549 cells [34]. Therefore, membrane stress pathway may be involved in MTX-induced apoptosis, though further studies are needed.

The cytotoxic effects and the induction of EMT by chemotherapeutic agents, including MTX, have been independently characterized, which has generated gaps in the knowledge about EMT and apoptosis. In the present study, by using inhibitors against apoptosis and EMT, we found that QVD, an apoptosis inhibitor, and SB, an EMT inhibitor, had no inhibitory effect on the MTX-induced EMT and apoptosis, respectively. In addition, there was no correlation between apoptosis and EMT induced by MTX treatment in isolated cloned cells, indicating that different mechanisms were responsible for MTX-induced apoptosis and the MTX-induced EMT in A549 cells. Furthermore, a positive correlation in the mRNA expression of CDKN1A and α-SMA was observed in MTX-treated cloned cells, suggesting the significant contribution of the p53-p21 axis to the MTX-induced EMT. These findings indicated that MTX-induced apoptosis and the MTX-induced EMT may occur independently, which would contribute to development of specific preventive approach against anticancer drug-induced EMT, and help to maintain the cytotoxic effects of anticancer drugs.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JP18H02586, JP18K06749, and JP19K16447).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Takamichi Ojima and Masashi Kawami have contributed equally to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Chen T, You Y, Jiang H, Wang ZZ. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT): a biological process in the development, stem cell differentiation, and tumorigenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232:3261–3272. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RYJ, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salton F, Volpe MC, Confalonieri M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Meddicina. 2019;55:83. doi: 10.3390/medicina55040083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Investig. 2003;112:1776–1784. doi: 10.1172/JCI20530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dongre A, Weinberg RA. New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial–mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:69–84. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly EC, Freimuth J, Akhurst RJ. Complexities of TGF-β targeted cancer therapy. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:964–978. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen KJ, Li Q, Wen CM, Duan ZX, Zhang JY, Xu C, Wang JM. Bleomycin (BLM) induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cultured A549 cells via the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway. J Cancer. 2016;7:1557–1564. doi: 10.7150/jca.15566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu J, Liu D, Niu H, Zhu G, Xu Y, Ye D, Li J, Zhang Q. Resveratrol reverses doxorubicin resistance by inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through modulating PTEN/Akt signaling pathway in gastric cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:19. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0487-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawami M, Harabayashi R, Miyamoto M, Harada R, Yumoto R, Takano M. Methotrexate-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition in the alveolar epithelial cell line A549. Lung. 2016;194:923–930. doi: 10.1007/s00408-016-9935-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kubo K, Azuma A, Kanazawa M, et al. Japanese Respiratory Society Committee for formulation of consensus statement for the diagnosis and treatment of drug-induced lung injuries, consensus statement for the diagnosis and treatment of drug-induced lung injuries. Respir Investig. 2013;51:260–277. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto A, Kawami M, Konaka T, Takenaka S, Yumoto R, Takano M. Anticancer drug-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition via p53/miR-34a axis in A549/ABCA3 cells. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2019;22:516–524. doi: 10.18433/jpps30660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawami M, Harada R, Ojima T, Yamagami Y, Yumoto R, Takano M. Association of cell cycle arrest with anticancer drug-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in alveolar epithelial cells. Toxicology. 2019;424:152231. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung JM, Cho HJ, Yi H, et al. Characterization of a stem cell population in lung cancer A549 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawami M, Harabayashi R, Harada R, Yamagami Y, Yumoto R, Takano M. Folic acid prevents methotrexate-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition via suppression of secreted factors from the human alveolar epithelial cell line A549. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;497:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.02.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takano M, Naka R, Sasaki Y, Nishimoto S, Yumoto R. Effect of cigarette smoke extract on P-glycoprotein function in primary cultured and newly developed alveolar epithelial cells. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2016;31:417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.dmpk.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morandi A, Taddei ML, Chiarugi P, Giannoni E. Targeting the metabolic reprogramming that controls epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in aggressive tumors. Front Oncol. 2017;7:40. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer KR, Durrans A, Lee S, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is not required for lung metastasis but contributes to chemoresistance. Nature. 2015;527:472–476. doi: 10.1038/nature15748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang L. Investigating heterogeneity in HeLa cells. Nat Methods. 2019;16:281. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben-David U, Siranosian B, Ha G, et al. Genetic and transcriptional evolution alters cancer cell line drug response. Nature. 2018;560:325–330. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0409-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y, Pan X, Lei W, Wang J, Song J. Transforming growth factor-beta1 induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and apoptosis via a cell cycle-dependent mechanism. Oncogene. 2006;25:7235–7244. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Deiry WS. p21 (WAF1) mediates cell-cycle inhibition, relevant to cancer suppression and therapy. Cancer Res. 2016;76:5189–5191. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abbas T, Dutta A. P21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:400–414. doi: 10.1038/nrc2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grassi ML, Palma Cde S, Thomé CH, Lanfredi GP, Poersch A, Faça VM. Proteomic analysis of ovarian cancer cells during epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) induced by epidermal growth factor (EGF) reveals mechanisms of cell cycle control. J Proteomics. 2017;151:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li XL, Hara T, Choi Y, et al. A p21-ZEB1 complex inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition through the microRNA 183-96-182 cluster. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:533–550. doi: 10.1128/mcb.01043-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachman KE, Blair BG, Brenner K, et al. p21WAF1/CIP1 mediates the growth response to TGF-β in human epithelial cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:221–225. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.2.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Yan W, Jung YS, Chen X. PUMA cooperates with p21 to regulate mammary epithelial morphogenesis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. PLoS ONE. 2016;8:e66464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brosh R, Assia-Alroy Y, Molchadsky A, et al. p53 counteracts reprogramming by inhibiting mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:312–320. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Termén S, Tan EJ, Heldin CH, Moustakas A. p53 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by transforming growth factor β. J Cell Physiol. 2013;228:801–813. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang CJ, Chao CH, Xia W, et al. p53 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stem cell properties through modulating miRNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:317–323. doi: 10.1038/ncb2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z, Jiang Y, Guan D, et al. Critical roles of p53 in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahmanian N, Hosseinimehr SJ, Khalaj A. The paradox role of caspase cascade in ionizing radiation therapy. J Biomed Sci. 2016;23:88. doi: 10.1186/s12929-016-0306-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hattangadi DK, DeMasters GA, Walker TD, et al. Influence of p53 and caspase 3 activity on cell death and senescence in response to methotrexate in the breast tumor cell. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1699–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolesnick R. The therapeutic potential of modulating the ceramide/sphingomyelin pathway. J Clin Investig. 2002;110:3–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI16127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fekry B, Esmaeilniakooshkghazi A, Krupenko SA, Krupenko NI. Ceramide synthase 6 is a novel target of methotrexate mediating its antiproliferative effect in a p53-dependent manner. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0146618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]