Abstract

Although skin sensitization potential of various chemicals has been extensively studied, there are only a few reports on nanoparticles induced skin sensitization. Aiming to fill this lacuna, in this study we evaluated the potential of metal oxide nanoparticles (NPs) to induce skin sensitization with flow cytometry. Seven different metal oxide NPs, including copper oxide, cobalt oxide, nickel oxide, titanium oxide, cerium oxide, iron oxide, and zinc oxide were applied to Balb/c mice. After selecting the proper vehicle, the NPs were applied, and the skin sensitization potential were assessed using 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine with flow cytometry. Physiochemical properties such as hydrodynamic size, polydispersity, and zeta potential were measured for the NPs prior to the tests. All the seven metal oxide NPs studied showed negative responses for skin sensitization potential. These results suggest that the OECD TG 442B using 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine with flow cytometry can be applied to evaluate the potential of NPs for skin sensitization.

Keywords: Nanomaterials, Nanoparticles, Skin sensitization, Local lymph node assay, 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine

Introduction

The Guinea pig Maximisation Test (GPMT) has been used worldwide to evaluate the skin sensitization potential of substances [1]. The LLNA, an alternative to the conventional method that uses guinea pigs, was adopted as OECD TG 429 (Skin sensitization; Local Lymph Node Assay) in 2002 [2]. The LLNA is a skin sensitization test in which the proliferation of murine local auricular lymph node cells (LNCs) is measured after exposure of mice to test substances. However, the extensive use of LLNA has been restricted because it involves the use of radioisotope-labeled 3H-methyl thymidine, mainly due to difficulties in the disposal of radioactive waste in some countries. A flow cytometry based LLNA using 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (LLNA: BrdU-FCM) was developed as a novel non-radioactive model of the LLNA with a performance similar to that of the conventional LLNA method. This variant of LLNA was adopted as OECD TG442B in 2018 [3].

While there are many reports of skin sensitization potential induced by chemicals [4], only few studies that investigate the skin sensitization potential of nanoparticles (NPs) are available. Since nanoparticles released into environments may enter the human body and can cause potential damage to organs [5, 6], it is pertinent to study the skin sensitization potential of different NPs to assess the risks they pose to public health.

Because of their unique physicochemical properties compared to bulk chemicals, metal oxide NPs have been used for various applications in several fields, including electrical, pharmaceuticals, and biomedical fields [7]. While their physicochemical properties such as small size, altered solubility, and higher surface charge, these properties can lead to various adverse effects on human body. Very small size, which is characteristic of nanoparticles, results in an increase in the surface area and consequently, high toxicity. Thus, small NPs are generally more toxic than large particles of the same composition [8]. Since NPs tend to remain in the body under physiological conditions, it is essential to analyze their physicochemical properties that influence their in vivo persistence [9–11]. Moreover, nanoparticles exhibit a tendency to agglomerate by a process favored by large number of weak forces between particles [12]. Agglomeration can produce different biological effects as compared with well-dispersed NPs, therefore degree of dispersion is critical while determining the toxicity of NPs. Dispersion of nanoparticles is increased by coating the unstable surface of the NPs using a dispersant and a dispersion stabilizer, such as human, bovine, and mouse serum albumin, Tween80 and mouse serum [13].

Several studies have reported the toxicological profiles of different kinds of NPs on using different model systems. Using the LLNA BrdU-ELISA, Park et al. [14] demonstrated that titanium oxide NPs do not induce skin sensitization in mice. It has been shown that gold NPs can non-covalently bind to proteins and have an effect on the immune system [15]. Moreover, NPs may release free chemicals after being applied, and these free chemicals may have skin sensitization properties [16, 17]. However, there are little information about the skin sensitization potential of nanoparticles.

Therefore, this study was performed to evaluate the skin sensitization potential of metal oxide nanoparticles using the LLNA:BrdU-FCM.

Materials and methods

Nanoparticles

Seven metal oxide NPs of well-defined morphology were selected for this study (Table 1). Cerium oxide (CeO2, 15–30 nm), cobalt oxide (Co3O4, 50–80 nm), copper oxide (CuO, 30–50 nm) and titanium dioxide (TiO2, 15 nm) NPs were purchased from Nanoamor (Houston, USA). Iron oxide (Fe2O3, 100 nm) NPs were purchased from American Elements (Los Angeles, USA). Nickel oxide (NiO, 10–20 nm) NPs were purchased from US-nano (Houston, USA). Zinc oxide (ZnO, 20 nm) NPs were purchased from Sumitomo (Osaka, Japan).

Table 1.

Information of the seven metal oxide nanoparticles studied

| Nanoparticles (NPs) | CAS R.N | Primary size | Physical form | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerium oxide (CeO2) | 1306-38-3 | 15–30 nm | Solid (powder) | Nanoamor |

| Cobalt oxide (Co3O4) | 1308-06-1 | 50–80 nm | Solid (powder) | Nanoamor |

| Copper oxide (CuO) | 1317-38-0 | 30–50 nm | Solid (powder) | Nanoamor |

| Iron oxide (Fe2O3) | 1309-37-1 | 100 nm | Solid (powder) | American Element |

| Nickel oxide (NiO) | 1313-99-1 | 10–20 nm | Solid (powder) | US-nano |

| Titanium dioxide ( TiO2) | 13,463-67-7 | 15 nm | Solid (powder) | Nanoamor |

| Zinc oxide (ZnO) | 1314-13-2 | 20 nm | Solid (powder) | Sumitomo |

Nanoparticles characterization

Primary size of the NPs was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, LEO-912AB OMEGA, LEO, Germany). The hydrodynamic diameter was measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and the zeta potential was measured by electrophoretic light scattering (ELS); both measurements were performed using a Zetasizer-Nano ZS (Malvern, UK). In addition, to confirm that the NPs were not contaminated with endotoxins, Endpoint Chromogenic Limulus Amoebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay (Cambrex, USA) was performed.

Animal

Female BALB/C mice (7 weeks old, Specific Pathogen Free) were purchased from OrientBio co. (Korea) and acclimated for at least 5 days before experiments. The animals were kept at an animal facility in the Korea Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. The studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (2018, Approval NO. MFDS-18–145). The animals were housed at a temperature of 22 ± 3 ℃ and a relative humidity of 30–70%. The room was lit with artificial light for 12 h per day. The animals were given access to solid diets and sterilized drinking water. The animals were randomly selected with body weight measurement (2 mice per group for pre-screen tests and 4 mice per group for the main test).

Preparation of the vehicle and highest concentrations

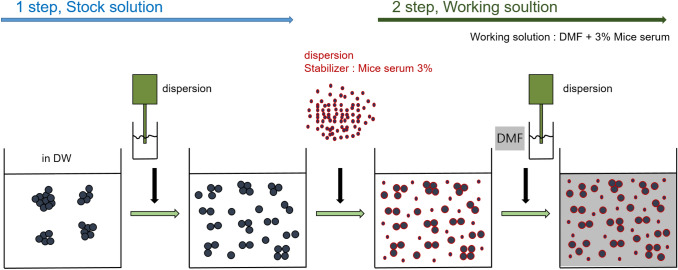

Prior to test, the dispersion of the NPs in different vehicles was determined to select appropriate test vehicles. This was carried out using the physicochemical analysis method for the vehicles suggested in OECD test guidelines 429 [2]. The vehicle was selected according to OECD test guideline TG 429. These include acetone: olive oil (4: 1 v/v, AOO), N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF), methyl ethyl ketone (MEK), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Since the NPs used in this study are insoluble, the solubility test was replaced by a dispersibility test to determine the proper dispersion of the NPs in the vehicle. Dispersants such as mouse serum, bovine serum albumin (BSA), polyethylene glycol (PEG), DMSO, and P.F-68 were selected to improve the dispersion and dispersion stability in test vehicle [18]. Among them, dispersion was performed using serum protein as reported by Bihari et al. [13] (Fig. 1). In order to increase the dispersity of the NPs, mouse serum was used in the experiments. The serum obtained from the abdominal vein of BALB/C mice was centrifuged (500 g/5 min) and inactivated by heating at 60 ℃ for 2 h. NPs stocks were prepared by dispersing them in distilled water and then finally dispersing in DMF with serum. For comparison with the serum group, we confirmed using DMF with P.F-68 dispersant. P.F-68 was purchased from Gibco (MD, USA).The vehicles used for the preparation of vehicles were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA).

Fig. 1.

Dispersion method of nanoparticle. Fig taken from Bihari et al. [13]. Nanoparticle was first dispersed in distilled water then finally dispersed in DMF including serum as dispersion stabilizer

Hydrodynamic sizes of the different NPs were determined to select the highest concentration. The concentration used in this study was measured hydrodynamic size of nanoparticle by first dispersing in distilled water then finally dispersing in DMF with serum. The highest concentration at which the hydrodynamic size of the nanoparticles remained constant while under one step of the size indicating statistical significance was selected as the maximum concentration. In the pre-screen test, 25% of the maximum concentration was used.

Pre-screening test

Pre-screen tests were performed as previously described in Ahn et al. [19] and based on recently revised OECD TG 442B (LLNA: BrdU-FCM) protocol. The first pre-screen test was performed with a single dose at 25% of the maximum concentration. On days 1, 2, and 3, 25 µL of the test solutions, vehicle control, and the positive control (PC) were applied on the back of each ear daily. PC was 25% hexyl cinnamic aldehyde in acetone: olive oil (4:1, v/v). Test solutions were prepared freshly before application. Mice were sacrificed on day 6 and both ears were collected using a 6 mm biopsy punch and were weighed. If toxicity or irritation were not found at 25%, only 50% and 100% concentrations were needed in the second test. If toxicity or irritation were found at 25%, the concentrations were lowered to 10%, 5%, 2.5%, 1%, 0.5% or below.

General symptoms were observed and recorded on each day. Erythema in the treated skin was scored in accordance with the Draize test method each day prior to the application of test substances. Body weights were measured on days 1 and 6. Ear thickness was measured at the center of both ears using Mitutoyo Quick Mini (Mitutoyo, Japan) on days 1, 3, and 6. The following observations were considered systemic toxicity or severe skin irritation: an erythema score ≥ 3, a decrease in body weight > 5%, an increase in ear weight or thickness ≥ 25% on day 6 compared with day 1, or death during the study.

Preparation of LNCs and FCM analysis

On day 5, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 100 µl of BrdU solution (20 mg/ml) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Gibco). On day 6, mice were sacrificed, and the auricular lymph nodes were collected and weighed. Lymph nodes were placed in a 70-µm nylon cell strainer (BD biosciences) and mashed with a cell scraper (SPL) to prepare LNCs. The LNCs were stained with trypan blue solution and then counted using a hemocytometer. The LNCs (1.5 × 106) were washed with PBS by centrifugation at 500×g for 10 min at 4 ℃. After supernatant was removed, the cells were fixed and permeabilized using cytofix/cytoperm buffer. After washing, the cells were resuspended with cytoperm permeabilization buffer and then fixed with cytofix/cytoperm buffer again. After repeat washing, the cells were treated with DNase at 37 ℃ in a water bath for 1 h to expose BrdU. Then, the cells were washed and stained with a FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. After one more wash, 7-AAD solution was added to label the DNA. LNCs (104 cells) were analyzed using BD FACS Calibur™ flow cytometry (BD Biosciences).

Stimulation index (SI) calculation

Experiment results are shown as the mean SI. SI values were calculated by the following equation.

If the SI values were above 2.7, test substance was classified as a skin sensitizer and if the SI values were below 2.7, test substance was classified as non-sensitizer [4].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 5 (Graph-Pad softwaew, Inc., CA, USA). All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviations. A p value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant (student’s t test).

Results

Proper selection of vehicle

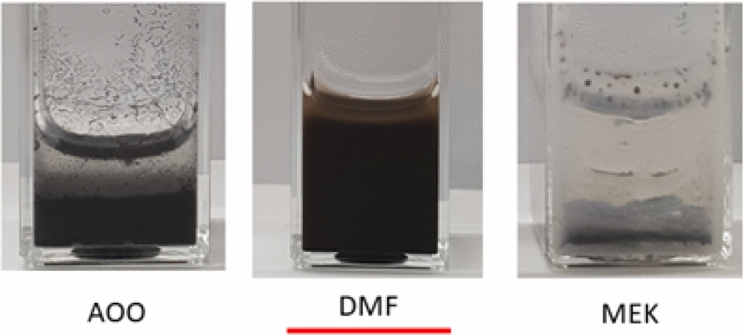

In this study, vehicles are selected depending on the characteristics of NPs. Vehicle selection test was performed using mouse serum as a dispersant (dispersion stabilizer). DLS studies showed that the hydrodynamic size of the NPs was significantly reduced in DMF. AOO and MEK were excluded from vehicle selection because DLS measurement was not possible due to layer separation. The dispersion stability of the NPs in DMF was confirmed as the size was maintained at 360 nm for 30 min at room temperature (Fig. 2, Table 2). Therefore, mouse serum containing DMF was finally selected as the vehicle.

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of dispersion stability of CuO nanoparticles using Mouse serum. After 30 min of dispersion, precipitation occurs through aggregation in the case of AOO and MEK vehicles

Table 2.

Measurement of Hydrodynamic Size in TG 442B Vehicle with 3% mouse serum Using CuO Nanoparticle

| Test NPs | CuO |

|---|---|

| Primary size (nm) | 30–50 |

| Hydrodynamic size (nm) | |

| In serum 3% AOO | Measure impossible |

| In serum 3% DMF | 373.7 ± 14.97 |

| In serum 3% MEK | Measure impossible |

Data were expressed as mean ± SD, n ≥ 5

Comparison of the results obtained from the dispersibility tests in mouse serum with other dispersants (P.F-68), showed that the hydrodynamic size of the nanoparticles (except NiO NPs) showed lower values in mouse serum. We confirm that mouse serum has higher dispersion stability than other dispersants (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of hydrodynamic size using 3% serum and 0.1% P.F-68 dispersant in 7 nanoparticles

| NPs primary size (nm) | Hydrodynamic size (nm) | Maximum dose (mg/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3% serum + DMF | 0.1% PF-68 + DMF | |||

| CeO2 | 15–30 | 502.4 ± 35.0 | 798.7 ± 23.25 | 15 |

| Co3O4 | 50–80 | 499.7 ± 74.4 | 541.6 ± 117.5 | 80 |

| CuO | 30–50 | 349.9 ± 7.2 | 1692 ± 356.8 | 90 |

| Fe2O3 | 100 | 447.6 ± 18.3 | 609.3 ± 24.68 | 30 |

| NiO | 10–20 | 490.9 ± 37.1 | 370.4 ± 9.01 | 25 |

| TiO2 | 15 | 793.8 ± 63.3 | 953.4 ± 117 | 25 |

| ZnO | 20 | 346.9 ± 9.6 | 1248 ± 42.81 | 10 |

Data were expressed as mean ± SD, n ≥ 5

In a dose selection test, the maximum concentration for each NPs was determined. The maximum concentration was found to be 15 mg/ml, 80 mg/ml, 90 mg/ml, 30 mg/ml, 25 mg/ml, 25 mg/ml and 10 mg/ml for CeO2, Co3O4, CuO, Fe2O3, NiO, TiO2, and ZnO NPs, respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Proper selection of maximum concentration (100% w/v) for topical application of TG 442B for 7 nanoparticles. A. CeO2, B. Co3O4, C. CuO, D. Fe2O3, E. NiO, F. TiO2, G. ZnO, Data were expressed as mean ± SD (n ≥ 5, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001)

Physicochemical properties of the NPs

In order to apply nanoparticles to the OECD TG 442B test, physicochemical properties such as hydrodynamic size, polydispersity, and zeta potential of the NPs dispersed in the vehicle (DMF/mouse serum) were analyzed. The physicochemical properties showed that the hydrodynamic size was in the range of 350–790 nm, and the polydispersity in the vehicle was generally below 0.5, except for CeO2 and Co3O4 NPs. In zeta potential measurements, almost all NPs showed values close to − 30 mV due to protein corona formation. The results of physicochemical properties confirmed that the dispersion stability was increased in the vehicle containing mouse serum (Table 4).

Table 4.

Physicochemical properties of 7 nanoparticles

| Nanoparticles (NPs) | CeO2 | Co3O4 | CuO | Fe2O3 | NiO | TiO2 | ZnO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary size (nm) | 15–30 | 50–80 | 30–50 | 100 | 10–20 | 15 | 20 |

| TEM average size (nm) | 14.23 ± 3.99 | 41.12 ± 12.06 | 47.80 ± 13.24 | 86.03 ± 18.10 | 19.10 ± 5.97 | 12.81 ± 2.70 | 20.66 ± 5.58 |

| Hydrodynamic size (d.nm) | |||||||

| In working solutiona | 502.4 ± 35.0 | 499.7 ± 74.4 | 349.9 ± 7.2 | 447.6 ± 18.3 | 490.9 ± 37.1 | 793.8 ± 63.3 | 346.9 ± 9.6 |

| Polydispersity (PDI) | |||||||

| In working solution | 0.54 ± 0.07 | 0.61 ± 0.19 | 0.30 ± 0.10 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.10 | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.05 |

| Zetapotential (mV) | |||||||

| In working solution | 32.9 ± 1.6 | 33.5 ± 1.6 | 26.5 ± 0.6 | 30.3 ± 0.9 | 32.9 ± 0.9 | 34.1 ± 1.0 | 31.2 ± 0.4 |

| Molecular weight (g/mol) | 172 | 240.8 | 79.5 | 159.7 | 74.7 | 79.6 | 81.4 |

| Purity (%) | 99.5 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 99 | 99.7 | 99.5 |

| Endotoxin (EU/mL) | < 0.1 | ||||||

Data were expressed as mean ± SD, n ≥ 5

aDMF contained 3% serum

Stimulation index in BALB/C

The stimulation index was obtained by flow cytometry. SI was calculated based on the total number of LNCs and BrdU incorporation in LNCs at three different doses. For all the seven metal oxide NPs, the SI was less than 2.7 and therefore, they were evaluated as non-sensitizers in BALB/C (Table 5), the SI value of PC was in above 2.7, which indicated a skin sensitization response. For comparison, tests were performed using DMF/P.F-68 dispersant. The results showed that SI of four metal oxide NPs (CeO2, Co3O4, CuO, and NiO) was less than 2.7 and were therefore classified as non-sensitizers (Table 6).

Table 5.

Comparison of stimulation index values in Metal Oxide NPs

| Nanoparticles (NPs) | Dose (%) | Vehicle | SI (mean ± SD) | N/S | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VC | L | M | H | PC | ||||

| CeO2 | 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 3% serum | 1.00 ± 0.09 | 1.81 ± 0.67 | 2.15 ± 0.36 | 1.86 ± 0.65 | 5.58 ± 0.72 | N |

| Co3O4 | 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 3% serum | 1.00 ± 0.31 | 1.17 ± 0.66 | 0.86 ± 0.11 | 1.04 ± 0.33 | 3.22 ± 1.44 | N |

| CuO | 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 3% serum | 1.00 ± 0.70 | 0.92 ± 0.12 | 1.08 ± 0.20 | 0.75 ± 0.30 | 3.37 ± 1.55 | N |

| Fe2O3 | 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 3% serum | 1.00 ± 0.14 | 1.11 ± 0.49 | 0.91 ± 0.22 | 0.97 ± 0.42 | 5.05 ± 0.98 | N |

| NiO | 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 3% serum | 1.00 ± 0.62 | 1.88 ± 0.51 | 1.78 ± 0.41 | 1.80 ± 0.33 | 5.10 ± 1.40 | N |

| TiO2 | 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 3% serum | 1.00 ± 0.14 | 0.73 ± 0.17 | 0.80 ± 0.18 | 0.78 ± 0.22 | 3.79 ± 0.98 | N |

| ZnO | 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 3% serum | 1.00 ± 0.09 | 1.51 ± 0.62 | 1.66 ± 0.68 | 0.92 ± 0.12 | 5.58 ± 0.72 | N |

S sensitizer, N non sensitizer

Data were expressed as mean ± SD, n = 4, “n” indicates number of mouse

Table 6.

Comparison of stimulation index values using P.F-68 dispersant in 4 Metal Oxide NPs

| Nanoparticles (NPs) | Dose (%) | Vehicle | SI (mean ± SD) | N/S | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VC | L | M | H | PC | ||||

| CeO2 | 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 3% serum | 1.00 ± 0.09 | 1.81 ± 0.67 | 2.15 ± 0.36 | 1.86 ± 0.65 | 5.58 ± 0.72 | N |

| 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 0.1% PF-68 | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 1.98 ± 0.54 | 1.69 ± 0.62 | 1.04 ± 0.26 | 4.00 ± 2.02 | N | |

| Co3O4 | 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 3% serum | 1.00 ± 0.31 | 1.17 ± 0.66 | 0.86 ± 0.11 | 1.04 ± 0.33 | 3.22 ± 1.44 | N |

| 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 0.1% PF-68 | 1.00 ± 0.41 | 0.99 ± 0.33 | 0.71 ± 0.31 | 0.53 ± 0.13 | 3.96 ± 1.56 | N | |

| CuO | 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 3% serum | 1.00 ± 0.70 | 0.92 ± 0.12 | 1.08 ± 0.20 | 0.75 ± 0.30 | 3.37 ± 1.55 | N |

| 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 0.1% PF-68 | 1.00 ± 0.37 | 1.34 ± 0.67 | 1.35 ± 0.53 | 1.21 ± 0.88 | 4.01 ± 1.90 | N | |

| NiO | 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 3% serum | 1.00 ± 0.62 | 1.88 ± 0.51 | 1.78 ± 0.41 | 1.80 ± 0.33 | 5.10 ± 1.40 | N |

| 25, 50, 100 | DMF + 0.1% PF-68 | 1.00 ± 0.57 | 1.14 ± 0.33 | 1.51 ± 0.46 | 1.21 ± 0.62 | 3.59 ± 1.03 | N | |

S sensitizer, N non sensitizer

Data were expressed as mean ± SD, n = 4, “n” indicates number of mouse

Discussion

The current understanding of the chemical and the biological mechanisms associated with skin sensitization has been summarized in the form of an adverse outcome pathway (AOP), starting with the molecular initiating event through intermediate events to the adverse effects, namely allergic contact dermatitis [20]. Lymph nodes or T cell differentiation is the key event No.4 (organ responses) of AOP for skin sensitization, which is indirectly assessed in LLNA, an in vivo murine assay [21].

Because of their unique physical and chemical properties, NPs are being widely used in various fields. Although the development of nanotechnology in various fields has benefited human life in the modern society, the physicochemical properties of the NPs can also elicit toxicity. Furthermore, the extent and efficacy of biological activities of NPs is affected by changes in their physicochemical properties. Because changes in the biological efficacy can lead to different test results, it is important to consider the physicochemical properties of nanoparticles while assessing the toxicity profiles of various NPs.

Skin sensitization study for ZnO and TiO2 NPs has been performed using LLNA:BrdU-ELISA assay or using TG 406 [14, 22, 23]. In these reports, the NPs were determined to be non-sensitizers. Similarly, Cho et al. [6] reported that metal oxide nanoparticle did not induce skin sensitization in an in vitro test. Although there are some studies in the literature that show nanomaterials as skin sensitizers, the test results in these studies are inadequate to demonstrate skin-sensitization potential of these nanomaterials.

LLNA:BrdU-FCM method was developed to replace the traditional radioisotopic LLNA, this method could reduce the pain inflicted on animals as it does not use immunoadjuvants and the number of animals needed is reduced. This assay is based on the principle that sensitizers induce lymphocyte proliferation in the lymph nodes at the site of application. Lymphocyte proliferation is in proportion to the concentration and sensitization of the substance and the proliferation is measured using flow cytometry.

In this study, we intend to confirm the skin sensitization potential of metal oxide NPs can be tested using LLNA:BrdU-FCM rather than chemicals, which were used previously. To apply NPs for this test, physico-chemical properties of the NPs were considered. Specifically, their ability to disperse in the mouse serum was essential for accurate assessment of the toxicity. Comparative analysis of the hydrodynamic size of the NPs showed that dispersion stability of the NPs was higher in DMF containing mouse serum than in 0.1% PF-68 dispersant. The size of the NPs were lesser in the DMA/mouse serum vehicle than in the serum free 0.1% PF-68 dispersant.

In a pre-screen test, mice treated with seven different metal oxide NPs showed no systemic toxicity, excessive irritation, or changes in body weight, ear weight and ear thickness at 25, 50, and 100% maximum concentration. Thus, the NPs were classified as non-sensitizer. However, unlike common LLNA: BrdU-FCM assay using chemicals, we used NPs and confirmed whether the use of dispersant affects the experimental results. The results were confirmed by performing that assay in a serum free DMF containing 0.1% PF-68 dispersant with the same concentration of NPs. The SI of four metal oxide nanoparticle (CeO2, Co3O4, CuO, and NiO), measured using flow cytometry, were less than 2.7 in the mouse serum group. These results show that mouse serum does not affect the experimental results compared with other dispersants.

In conclusion, in this study, the seven metal oxide NPs showed negative response for skin sensitization potential. This is the first study to apply OECD 442B for evaluating the skin sensitization potential for nanoparticles. These results suggest that the OECD TG 442B using 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine with flow cytometry can be applied to evaluate the potential of NPs to induce skin sensitization. Although the NPs studied here show that they are non-sensitizer, the present result is relevant only for the application of the NPs on a normal skin. It is likely that NPs may need to penetrate the skin to cause sensitization. In this context, percutaneous permeation of nanoparticles has been actively studied in the past [24]. These studies demonstrated that penetration of NPs is negligible in intact skin but can be augmented by skin damage [25]. For this reason, we think the skin sensitization potential between compounds and nanoparticles is different. For example, Nickel compound is known as a skin sensitizer, but not Nickel nanoparticle. Since Nickel nanoparticles cannot penetrate into normal skin, we consider it non-sensitivity material. Therefore, further studies to determine the skin sensitization potential of NPs in different damaged skin models can be useful.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety [Grant Numbers 18181MFDS361 (2018, 2019)]. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (2018, Approval NO. MFDS-18-145).

References

- 1.OECD skin, Sensitisation . OECD Guideline for the testing of chemicals no. 406. Paris: OECD Publishing; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.OECD . Skin sensitization: local lymph node assay, OECD guidelines for chemical testing no. 429. Paris: OECD; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.OECD . Skin sensitisation: local lymph node assay: BrdU-ELISA, OECD guidelines for the testing of chemicals no. 442B. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han BI, Yi JS, Seo SJ, Kim TS, Ahn I, Ko, et al. Evaluation of skin sensitization potential of chemicals by local lymph node assay using 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine with flow cytometry. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2019;107:104401. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2019.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park J, Kwak BK, Bae E, Lee J, Kim Y, Choi K, Yi J. Characterization of exposure to silver nanoparticles in a manufacturing facility. J Nanopart Res. 2009;11:1705–1712. doi: 10.1007/s11051-009-9725-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho WS, Duffin R, Bradley M, Megson IL, MacNee W, Lee JK, et al. Predictive value of in vitro assays depends on the mechanism of toxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2013;10:55. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-10-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nel AE, Mädler L, Velegol D, Xia T, Hoek EM, Somasundaran P, et al. Understanding biophysicochemical interactions at the nano–bio interface. Nature Mater. 2009;8:543–557. doi: 10.1038/nmat2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warheit DB, Laurence BR, Reed KL, Roach DH, Reynolds GA, Webb TR. Comparative pulmonary toxicity assessment of single-wall carbon nanotubes in rats. Toxicol Sci. 2004;77:117–125. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang J, Oberdörster G, Biswas P. Characterization of size, surface charge, and agglomeration state of nanoparticle dispersions for toxicological studies. J Nanopart Res. 2009;11:77–89. doi: 10.1007/s11051-008-9446-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahmoudi M, Laurent S, Shokrgozar MA, Hosseinkhani M. Toxicity evaluations of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: cell “vision” versus physicochemical properties of nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2011;5:7263–7276. doi: 10.1021/nn2021088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gate L, Disdier C, Cosnier F, Gagnaire F, Devoy J, Saba W, Mabondzo A. Biopersistence and translocation to extrapulmonary organs of titanium dioxide nanoparticles after subacute inhalation exposure to aerosol in adult and elderly rats. Toxicol Lett. 2017;265:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gosens I, Post JA, de la Fonteyne LJ, Jansen EH, Geus JW, Cassee FR, de Jong WH. Impact of agglomeration state of nano-and submicron sized gold particles on pulmonary inflammation. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bihari P, Vippola M, Schultes S, Praetner M, Khandoga AG, Reichel CA, et al. Optimized dispersion of nanoparticles for biological in vitro and in vivo studies. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2008;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park YH, Jeong SH, Yi SM, Choi BH, Kim YR, Kim IK, et al. Analysis for the potential of polystyrene and TiO2 nanoparticles to induce skin irritation, phototoxicity, and sensitization. Toxicol Vitro. 2011;25:1863–1869. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshioka Y, Kuroda E, Hirai T, Tsutsumi Y, Ishii KJ. Allergic responses induced by the immunomodulatory effects of nanomaterials upon skin exposure. Front Immunol. 2017;8:169. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dwivedi PD, Tripathi A, Ansari KM, Shanker R, Das M. Impact of nanoparticles on the immune system. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2011;7:193–194. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2011.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dykman LA, Khlebtsov NG. Immunological properties of gold nanoparticles. Chemical Sci. 2017;8:1719–1735. doi: 10.1039/C6SC03631G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.OECD . Test No. 318: dispersion stability of nanomaterials in simulated environmental media, OECD guidelines for the testing of chemicals, Section 3. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahn I, Kim TS, Jung ES, Yi JS, Jang WH, Jung KM, et al. Performance standard-based validation study for local lymph node assay: 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine-flow cytometry method. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2016;80:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.OECD . In vitro skin sensitisation: in vitro skin sensitisation assays addressing the key event on activation of dendritic cells on the adverse outcome pathway for skin sensitisation (OECD TG 442E) Paris: OECD Publishing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.OECD . Test No. 442B: skin sensitization: local lymph node assay: BrdU-ELISA or –FCM, OECD Guidelines for the testing of chemicals, section 4. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jang YS, Lee EY, Park YH, Jeong SH, Lee SG, Kim YR, et al. The potential for skin irritation, phototoxicity, and sensitization of ZnO nanoparticles. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2012;8:171–177. doi: 10.1007/s13273-012-0021-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SH, Heo Y, Choi SJ, Kim YJ, Kim MS, Kim H, et al. Safety evaluation of zinc oxide nanoparticles in terms of acute dermal toxicity, dermal irritation and corrosion, and skin sensitization. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2016;12:93–99. doi: 10.1007/s13273-016-0012-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bronaugh RL, Stewart RF. Methods for in vitro percutaneous absorption studies V: permeation through damaged skin. J Pharm Sci. 1985;74:1062–1066. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600741008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zanoni I, Crosera M, Ortelli S, Blosi M, Adami G, Filon FL, Costa AL. CuO nanoparticle penetration through intact and damaged human skin. New J Chem. 2019;43:17033–17039. doi: 10.1039/C9NJ03373D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]