Abstract

In this study, papain and alcalase were used to generate antioxidant peptides from yak bone protein. The antioxidant activities of hydrolysates in vitro were evaluated by 2,2′-azinobios-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) radical scavenging activity, total reducing power, ferrous ion chelating ability and hydroxyl radical scavenging activity. The hydrolysates generated by alcalase possessed the best antioxidant activity among unhydrolyzed protein and samples treated by papain, but the antioxidant activity decreased after simulated gastrointestinal digestion in vitro. The products of simulated gastrointestinal digestion were separated by ultrafiltration and high performance liquid chromatography, and the amino acid sequences of peptides were identified by mass spectrometry. The digestion sites within peptides were predicted by a bioinformatics strategy, and ten peptides were selected for synthesis. Among 10 synthetic peptides, Gly-Phe-Hyp-Gly-Ala-Asp-Gly-Val-Ala, Gly-Gly-Pro-Gln-Gly-Pro-Arg and Gly-Ser-Gln-Gly-Ser-Gln-Gly-Pro-Ala possessed strong antioxidant activities, among which Gly-Phe-Hyp-Gly-Ala-Asp-Gly-Val-Ala had a significant cytoprotective effect in Caco-2 cells under oxidative stress induced by H2O2, which reduced the formation of reactive oxygen species and malondialdehyde, and improved the activity of antioxidant enzymes in cells. These results showed that yak bone peptides exhibited strong antioxidant activity and have a potential value as a new type of natural antioxidant.

Keywords: Yak bone, Peptides, Antioxidant activities, Cytoprotective effect

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), produced during cellular respiration in aerobic organisms, can lead to oxidative stress and damage in cell or tissues (Chalamaiah et al. 2012). Oxidative stress is related to many human diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, hypertension, and neurodegenerative diseases (Young and Woodside 2001). Therefore, it is very important to remove ROS to maintain human health. The exploration of safe and natural antioxidants has arouse great interest in recent years.

After enzymatic hydrolysis, some of the released peptides exhibit excellent antioxidant activities in vitro (Kumar et al. 2012). Collagen and its derived peptides have the characteristics of strong antioxidant activity, strong biocompatibility and non-irritant to human body, which are important characteristics for application in medicine and food industry (Zhuang et al. 2009). Previous studies on collagen and gelatin hydrolysates have found peptides with antioxidant activity, e.g. peptides from thornback ray (Rajiformes) gelatin (Lassoued et al. 2015), Alaska pollack (Gadus chalcogrammus) skin gelatin (Kim et al. 2001), and silvertip shark (Carcharhinus albimarginatus) gelatin (Jeevithan et al. 2014).

The yak (Bos grunniens) mainly lives in high altitude areas, such as the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, and is a rare breed species of cattle with the ability of low temperature resistance and high endurance. The extreme living environment conditions make yak products better in texture, protein, fat and amino acid content than ordinary beef products (Zhao et al. 2019). As a main by-product of yak meat processing, yak bone is rich in nutrition, e.g. proteins and minerals (Li et al. 2009a, b). However, large amounts of yak bones were discarded without further utilization. Yak bone is rich in collagen, and the hydrolysates of bone collagen have a variety of potential biological activities (Gao et al. 2019) Chen et al. (2011). used proteases (papain, trypsin, alcalase, etc.) to hydrolyze yak bone protein and found that yak bone hydrolysates had antioxidant activity, among which hydrolysates hydrolyzed by alcalase and flavourzyme possessed the strongest antioxidant activity in the H2O2 system. Gao et al. (2019) demonstrated that yak bone hydrolysates had a good immunomodulatory effect on BALB/c mice, which prevented immunosuppressive responses due to aging or inhibitors. However, there are few in-depth studies on the function of yak bone peptides, and many potential biological activities have not been exploited.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to purify and characterize the antioxidant peptides from yak bone and to study the protective effect on Caco-2 cells against oxidative stress. Two commercial proteases (alcalase and papain) were used to obtain yak bone hydrolysates in this study. The components with superior antioxidant activity in vitro were screened and purified, then its amino acid sequences were characterized. In addition, the cytoprotection of yak bone peptides was further investigated using Caco-2 oxidant stress model.

Materials and methods

Materials

Yak bone was provided by Anhui Guotai Biotechnology Co., Ltd. and was stored at −20 °C in the laboratory. Papain (Model PA-4) was purchased from Angel Yeast Co., Ltd. Alcalase (Model 2.4 L) was purchased from Novozymes (Bagsvaerd, Denmark).

Preparation of defatted collagen hydrolysates from yak bone

The extraction of yak bone collagen and the preparation of hydrolysates were based on the method of Gao et al. (2019) with some modifications. Dried yak bone was added to distilled water (1: 6, w/v) and then heated at 121 °C for 4 h to obtain yak bone collagen. The fat on the surface and bone residue were removed. The solution was divided into glass dishes and frozen at −18 °C for 12 h. The frozen samples were put into the lyophilizer with the cold trap temperature of −56 °C and the freeze–drying time was 48 h. The freeze-dried protein powder with protein content of (92.23 ± 0.33%) was obtained.

The protein powder was re-dissolved in distilled water (1:10, w/v), and the derived solution was divided into two parts. The temperature and pH of the solution were adjusted to the optimum conditions of corresponding protease (Papain: 55 °C and pH 7.0; Alcalase: 55 °C and pH 8.0). Papain and alcalase were added to the two groups respectively at 4500 unit of enzymes were added per gram of hydrolysates in solutions, and equal amounts of samples were taken at the pre-set time point (0.5, 1, 2, 3 and 4 h). The solution was heated at 95 °C for 15 min to inactivate enzyme, cooled to room temperature and then freeze-dried to obtain yak bone hydrolysates for further analysis.

Reducing power

Reducing power was measured according to the method of Agrawal et al. (2016) with slightly modifications. Sample solution (1 mL) was mixed with sodium phosphate buffer (0.2 mM, pH 6.6) and 1% (w/v) K3Fe(CN)6. After 20 min at 50 °C, 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid was added and centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min. The supernatant (2.5 mL) was added to distilled water (2.5 mL) and 0.1% (w/v) FeCl3 (0.5 mL), and reacted at room temperature for 10 min. The absorbance of the solution at 700 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer (UNICO UV-2600A).

2,2′-azinobios-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS) radical scavenging activity

ABTS radical scavenging was determined by Devi et al. (2017). The ABTS solution (7 mM) was mixed with an equal volume of potassium persulfate solution (2.45 mM) and the ABTS + working solution was obtained at room temperature for 12–16 h. The ABTS+ working solution was diluted with a phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 7.4) before the measurement (absorbance = 0.7 ± 0.02, 732 nm). The sample solution was added to ABTS+ dilution and the reaction was conducted at room temperature for 10 min in the dark. The absorbance was measured at 732 nm and distilled water was used as a blank control.

Ferrous ion (Fe2+) chelating activity

The determination of ferrous ion chelating rate was determined by the method of Chen et al. (2009). The sample solution was mixed with FeCl2 (0.2 mM) and Ferrozine (5 mM). After 10 min at 25 °C, the absorbance of the solution was measured at 562 nm.

Hydroxyl radical (OH·) scavenging activity

The hydroxyl radical scavenging activity was determined by Sakanaka and Tachibana (2006). The sample solution was sequentially mixed with sodium phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 7.4), 2-deoxyribose (10 mM), FeSO4-EDTA (10 mM), distilled water, and hydrogen peroxide (10 mM) was added. After 1 h at 37 °C, 2.8% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid and 1% (w/v) thiobarbituric acid were added and heated in boiling water for 10 min. The solution was cooled and its absorbance was measured at 532 nm.

In vitro simulated gastrointestinal (GI) digestion

After the hydrolysate solution (30 mg/mL) was heated to 37 °C in a water bath, the pH was adjusted to 2.0 using HCl (5 M). Pepsin (enzyme: substrate ratio, 1:50 w/w) was added to the solution to initiate in vitro gastric mimic digestion (1 h). The pH was then adjusted to 5.3 using NaHCO3 (1 M) and further adjusted to 7.5 with NaOH (5 M). Thereafter, pancreatin (enzyme: substrate ratio, 1:25 w/w) was added to mimic intestinal digestion (2 h). The resulted solution was centrifuged (12,000 × g, 10 min) and the supernatant was lyophilized to obtain the simulated digested protein powder.

Molecular weight distribution

The method for determining the molecular weight was described with reference to the method of Xie et al. (2014) with minor modifications. The molecular weight (MW) of the sample was analyzed by size exclusion high performance liquid chromatography (SE-HPLC) (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Tokyo, Japan). A mobile phase containing trifluoroacetic acid (0.1% (v/v)) and acetonitrile (45% (v/v)) was prepared using ultrapure water. The peptide sample solution (2 mg/mL) was filtered using a microfiltration membrane (0.45 μM), and the solution (25 μL) was taken and injected into a TSK gel G2000 SWXL column (7.8 × 300 mm, TOSOH, Tokyo, Japan) for elution. The elution flow rate at the time of elution was set to 0.5 mL/min, and the wavelength of ultraviolet light was set to 214 nm. Cytochrome c (12,362 Da), aprotinin (6511.4 Da), bacitracin (1423 Da), Gly-Gly-Tyr-Arg (451 Da) and Gly-Gly-Gly (189 Da) were used as the standard, and the calibration curve between retention time and the logarithm of molecular weight was established.

Ultra-filtration

Yak bone hydrolysates were separated by ultrafiltration to obtain components of different molecular weights (MW > 1 kDa, MW < 1 kDa) (Zhang et al. 2019). Different samples were lyophilized and the components with better antioxidant activity were screened for further analysis.

Reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC)

The fraction obtained by ultrafiltration was further purified using RP-HPLC with a Kromasil 100-5-C18 semi-preparation column (4.6 × 250 mm, Kromasil Technologies Co. Ltd., SE-445 80Bohus, Sweden). The chromatographic conditions were as follows:

Mobile phase A: Ultrapure water containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid; Mobile phase B: Acetonitrile containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid; Injection volume: 50 μL; sample concentration: 30 mg/mL; Detection wavelength: 220 nm; Elution procedure: Mobile phase B from 5 to 65% (0–25 min); Mobile phase B from 65 to 5% (25–30 min).

The different fractions were divided and the eluates of each group were combined and concentrated. The antioxidant activities of different components were determined, and the optimal components were selected for identifications by mass spectrometry.

Sequencing of peptides by LC–MS/MS

Mass spectrometry (Thermo Q-Exactive) was used to identify the components with better antioxidant activity after RP-HPLC separation. The Swiss-Prot protein database was searched by Mascot 2.4 search engine software (Matrix Science, Boston, MA, USA) to determine the amino acid sequence of the target peptide.

Synthesis of peptide

The peptides with a molecular weight less than 1 kDa were selected and 10 peptides were synthesized according to the possible structural characteristics of antioxidant peptides and the number of enzyme cutting sites contained in peptides. The synthesis of the peptides was performed by Shanghai RoyoBiotech Co., Ltd.

Cell culture

Caco-2 cells were grown in Dulbeco's modified eagle's medium (containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin) with 5% CO2 and a temperature of 37 °C. When the cells occupied about 80% of the bottom of the culture flasks (25 cm2), trypsin digestion solution was added to digest the cells. Then the cells were blown apart, placed into the new culture flasks, and cultured in the cell incubator.

Cytoprotective effect

5 × 104 cells/mL Caco-2 cells were added to a 96-well plate cultured for 18 h. Thereafter, antioxidant peptides (final concentration of 30 μg/mL) were added and the cells were cultured for 24 h. Cells were incubated with H2O2 (1 mM) for 1 h to induce oxidative stress. The medium was removed and replaced with 200 μL 3- (4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) -2,5-diphenyltetrazole bromide (MTT, 0.5 mg/mL) for further incubation (4 h). The medium was discarded and 150 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added, and the absorbance was monitored at 490 nm.

Cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) determination

The cellular ROS was determined according to Wang et al. (2016) using a DCFH-DA fluorescent probe. The Caco-2 cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) after being treated with peptides and H2O2. DCFH-DA fluorescent probe solution (10 μM 200 μL) was added and the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. The reaction system was washed twice with complete medium, and the fluorescence intensity was measured at the excitation wavelength of 485 nm and the emission wavelength of 530 nm. Results were expressed by the percentage of relative fluorescence intensity between the experimental and control group.

Malondialdehyde (MDA) and antioxidant enzyme activities

The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and malondialdehyde (MDA) level were determined using SOD assay kit, CAT assay kit and MDA assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Jiangsu, China). The protein concentration in the cell lysate was measured using the BCA assay kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed in triplicate using Excel 2016 and SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Differences between means were analyzed by the Least Significant Difference Method (LSD) at a significance level of 0.05. The results of the experimental data were expressed as "average ± standard deviation".

Results

Antioxidant activity and molecular weight distribution of yak bone hydrolysates

The antioxidant activity of hydrolysates was evaluated by ABTS radical scavenging ability, hydroxyl radical (OH·) scavenging activity, reducing power, and ferrous ion (Fe2+) chelating activity (Fig. 1 a–d). Compared with unhydrolyzed protein, antioxidant activity of hydrolysates increased significantly with hydrolysis time (P < 0.05). The ABTS radical scavenging activity of the hydrolysates generated by papain was higher than that of alcalase before 2 h. The activity of the hydrolysates generated by alcalase was the highest at 2 h, reaching 32.42%. Reducing power and hydroxyl radical scavenging activity showed similar trends, both characterized as sharp increases within 2 h and then decreases with prolonged hydrolysis. Hydrolysis for 2 h by alcalase resulted in the strongest hydroxyl scavenging activity (27.26%) and reducing power (0.187). During the whole enzymatic hydrolysis process, the activity of hydrolysates generated by alcalase was higher than that of papain. The ferrous ions chelating activity increased significantly (P < 0.05) after the hydrolysis of protein, and did not change obviously afterwards.

Fig. 1.

Antioxidant activity and molecular weight distribution of yak bone hydrolysates. a ABTS radical scavenging activity. b Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity. c Reducing power. d Ferrous ion chelating activity. e Molecular weight distribution. The same lowercase letter of each group indicates no significant difference in values (P > 0.05)

The molecular weight (MW) distribution of yak bone hydrolysates was shown in Fig. 1e. About 74% of the unhydrolyzed proteins had molecular weights above 10 kDa. In contrast, the percentage of high molecular weight of hydrolysates reduced significantly after yak bone protein was hydrolyzed by papain and alcalase (P < 0.05). The MW distribution of hydrolysates generated by papain did not change significantly with hydrolysis time, and the proportion of the hydrolysates with MW less than 1 kDa was 40–45%. The proportion of low MW (MW < 1 kDa) in hydrolysates generated by alcalase increased with hydrolysis time accounting for 31.30 and 40.48% for substances below 0.5 kDa and 0.5–1 kDa, respectively.

The results of antioxidant activity showed that the yak bone hydrolysate prepared by alcalase for 2 h (Referred to as YBH, the same below) possessed good antioxidant activity, so YBH was selected for further analysis.

Simulated gastrointestinal (GI) digestion in vitro and ultrafiltration separation of yak bone hydrolysate

After simulated gastrointestinal digestion of YBH in vitro, the antioxidant activity and MW distribution of the products (GI-YBH) were determined (Fig. 2). The ferrous ion chelating activity increased to 97.34%, however, ABTS radical scavenging ability, hydroxyl radical scavenging activity and reducing power all decreased to 24.80%, 19.86% and 0.169%, respectively. As for MW distribution, components with MW < 1 kDa increased significantly to 79.82%, including MW < 0.5 kDa (48.22%) and 0.5–1 kDa (31.60%).

Fig. 2.

Antioxidant activity and molecular weight (MW) distribution of GI-YBH and its different ultrafiltration fractions. Fa: MW > 1 kDa. Fb: MW < 1 kDa. a ABTS radical scavenging activity. b Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity. c Reducing power. d Ferrous ion chelating activity. e Molecular weight distribution. The same lowercase letter indicates no significant difference in values (P > 0.05)

GI-YBH was separated into Fraction a (Fa, MW > 1 kDa) and Fraction b (Fb, MW < 1 kDa) by ultrafiltration and their antioxidant activity were determined. The ferrous ion chelation activity, ABTS radical scavenging activity and reducing power of Fb were 97.33%, 26.26% and 0.171%, respectively, which were higher than Fa (73.06%, 23.82% and 0.163%, respectively). However, the hydroxyl radical scavenging activity (16.99%) of Fb was lower than Fa (24.67%). Therefore, Fb was selected for subsequent RP-HPLC separation based on its excellent antioxidant activity.

Isolation of yak bone hydrolysate by RP-HPLC

Fb was further purified by RP-HPLC and then six fractions were split according to the hydrophobicity of components (Fig. 3a). The obtained samples were evaporated and concentrated to adjust the protein concentration to 1 mg/mL for the determination of antioxidant activity (Fig. 3b–e). The ABTS scavenging activity of F5 was the highest (65.38%), and the lowest (4.01%) was F1. Among all fractions, F2 showed the strongest hydroxyl radical scavenging activity with 18.49%, followed by F3 (15.16%) and F5 (14.97%). The reducing power of F5 was 0.198, while the minimum reducing power (0.132) was detected in F3. According to the antioxidant activity, F5 was selected for LC–MS/MS identification.

Fig. 3.

RP-HPLC elution curve of Fb and comparison of antioxidant capacity of different eluted fractions. a Elution curve (F1-F6). b ABTS radical scavenging activity. c Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity. d Reducing power. e Ferrous ion chelating activity. The same lowercase letter indicates no significant difference in values (P > 0.05)

Screening of peptides and determination of antioxidant activity

Bone collagen belongs to type I collagen, which is composed of two α1 chains and one α2 chain. Therefore, the most abundant components of Fb are the peptides originated from collagen (I) α1 and α2 chain. A total of 61 peptides with MW < 1 kDa were identified, of which 35 were from α1 chain and 26 were from α2 chain (Table 1a–b). Most peptides contained the repeated sequence of Gly-X-Y (X and Y are amino acids) and hydroxyproline (Hyp, represented by P), the characteristic amino acid of collagen. PeptideCutter software (https://web.expasy.org/peptide_cutter/peptidecutter_enzymes.html) was used to predict the GI digestive stability of peptide sequences. The cleavages of chymotrypsin, pepsin and trypsin with low specificity were selected to predict the cleavage sites of gastrointestinal enzymes in the polypeptide sequence, and number of cleavage sites was calculated. The peptides were screened according to −10lgP, the total number of cleavage sites and the structural characteristics of antioxidant peptides. Ten peptides were selected from the LC-MS/MS identification, which were Gly-Phe-Hyp-Gly-Leu-Pro-Gly-Pro-Ser (P1), Gly-Val-Val-Gly-Leu-Hyp-Gly-Gln (P2), Gly-Phe-Hyp-Gly-Ala-Asp-Gly-Val-Ala (P3), Gly-Glu-Ala-Gly-Pro-Ser-Gly-Pro-Ala (P4), Gly-Gly-Pro-Gln-Gly-Pro-Arg (P5), Gly-Val-Pro-Gly-Pro-Pro-Gly-Ala-Val (P6), Gly-Pro-Ser-Gly-Asp-Pro-Gly-Lys (P7), Gly-Ser-Gln-Gly-Ser-Gln-Gly-Pro-Ala (P8), Gly-Pro-Ala-Gly-Pro-Ser-Gly-Pro-Ala-Gly (P9), and Gly-Glu-Arg-Gly-Leu-Hyp-Gly-Val-Ala (P10). Most of these peptides contained hydrophobic amino acids such as Phe, Pro, Ala and Val. The antioxidant activity of peptides at a concentration of 1 mg/mL was determined (Fig. 4). GGPQGPR (P5) had good reducing power of 0.234; GFPGADGVA (P3) possessed good hydroxyl radical scavenging activity (17.00%); GSQGSQGPA (P8) was the best in ferrous ion chelating ability and ABTS radical scavenging ability, reaching 35.23 and 32.90%, respectively.

Table 1.

Peptide sequences identified from Collagen a alpha-1 (I) chain, b alpha-2 (I) chain

| Peptide | −10lgP | Mass | m/z | Cleavage site | PTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | |||||

| GFPGLPGPS | 68.94 | 843.4126 | 844.42 | 2 | Hydroxylation |

| GFSGLDGAK | 67.01 | 850.4185 | 426.2163 | 6 | / |

| GFPGLPGPS | 63.34 | 843.4126 | 844.42 | 2 | Hydroxylation |

| GFPGADGVAG | 59.13 | 862.3821 | 863.3894 | 1 | Hydroxylation |

| GVVGLPGQR | 56.3 | 897.5032 | 449.7588 | 1 | Hydroxylation |

| RGAPGPAGPK | 51.97 | 922.4984 | 308.5064 | 1 | Hydroxylation |

| FSGLDGAK | 49.22 | 793.397 | 397.7053 | 5 | / |

| GVVGLPGQ | 46.2 | 741.4021 | 371.7092 | 1 | Hydroxylation |

| GFSGLDG | 44.76 | 651.2864 | 652.295 | 6 | / |

| GFPGADGVA | 44.17 | 805.3606 | 806.3664 | 1 | Hydroxylation |

| GEAGPSGPA | 37.72 | 741.3293 | 742.3387 | 0 | / |

| GGPQGPR | 36.27 | 667.3401 | 334.6771 | 0 | / |

| GFSGLDGA | 35.78 | 722.3235 | 723.3297 | 6 | / |

| GVPGPPGAVGPA | 35.11 | 990.5134 | 496.2653 | 0 | Hydroxylation |

| PSGEPGK | 34.51 | 670.3286 | 336.1713 | 0 | / |

| GVPGPPGAV | 34.05 | 749.4072 | 750.4137 | 0 | / |

| GPAGERGAP | 33.83 | 810.3984 | 811.402 | 1 | / |

| GETGPAGPA | 33.45 | 755.345 | 756.3545 | 0 | / |

| GPSGPQGP | 30.81 | 695.3239 | 696.3359 | 0 | / |

| GAPGPAGPK | 30.64 | 766.3973 | 384.2062 | 0 | Hydroxylation |

| GFPGLPGPSG | 29.22 | 900.4341 | 901.4406 | 2 | Hydroxylation |

| GLPGPPGAP | 29.08 | 777.402 | 778.4111 | 1 | Hydroxylation |

| GVVGLPG | 28.23 | 613.3435 | 614.351 | 1 | Hydroxylation |

| GVPGPPGAVGPA | 28.14 | 990.5134 | 496.2642 | 0 | Hydroxylation |

| GETGPAGPPGA | 26.33 | 909.4192 | 910.4319 | 0 | / |

| GPPGSAGSPGK | 25.92 | 910.4508 | 456.232 | 0 | / |

| VGAPGPK | 25.92 | 640.3544 | 321.1844 | 0 | Hydroxylation |

| GETGPAGPAGP | 25.87 | 909.4192 | 910.432 | 0 | / |

| LPGPPGER | 25.6 | 821.4395 | 411.727 | 1 | / |

| GHRGFSGL | 25.43 | 829.4194 | 415.7166 | 4 | / |

| DGVAGPK | 22.93 | 642.3337 | 322.1762 | 0 | / |

| GPRGETGPA | 21.16 | 840.4089 | 841.4142 | 1 | / |

| GEPGDAGAK | 20.75 | 816.3613 | 409.1877 | 0 | Hydroxylation |

| VGPPGPS | 20.33 | 609.3122 | 610.319 | 0 | / |

| GETGPAG | 20.21 | 587.2551 | 588.2629 | 0 | / |

| (b) | |||||

| GFDGDFYR | 68.57 | 975.4086 | 488.7121 | 8 | / |

| EGPVGLPGID | 67.11 | 968.4814 | 969.4894 | 1 | Hydroxylation |

| GPSGDPGKA | 51.68 | 784.3715 | 393.1953 | 1 | / |

| GEVGLPGLS | 45.27 | 843.4338 | 422.7244 | 3 | Hydroxylation |

| GIPGEFG | 45.25 | 691.3177 | 692.3241 | 3 | Hydroxylation |

| FDGDFYR | 43.33 | 918.3871 | 460.2002 | 7 | / |

| IGFPGPK | 40.8 | 730.4013 | 366.208 | 1 | Hydroxylation |

| GLVGEPGPA | 40.49 | 811.4075 | 812.415 | 3 | Hydroxylation |

| GPSGDPGK | 37.82 | 713.3344 | 714.3453 | 0 | / |

| GDGGPPGATGF | 36.56 | 947.3984 | 948.4061 | 1 | Hydroxylation |

| GPPGASGAPGPQ | 36.4 | 991.4723 | 992.4821 | 0 | / |

| GSQGSQGPA | 35.85 | 787.346 | 788.356 | 0 | / |

| GPAGPSGPAG | 34.85 | 766.3609 | 767.3641 | 0 | / |

| GERGLPGVA | 34.78 | 870.4559 | 436.2357 | 1 | Hydroxylation |

| NIGFPGPK | 34.67 | 844.4443 | 845.4507 | 1 | Hydroxylation |

| AGVMGPAG | 32 | 658.3109 | 659.3225 | 1 | / |

| KGPSGDR | 29.63 | 715.3613 | 716.3643 | 1 | / |

| GSPGERGE | 29.18 | 787.346 | 788.3563 | 1 | / |

| GIPGEFG | 29.06 | 675.3228 | 676.3256 | 3 | / |

| GEVGLPGL | 28.29 | 756.4017 | 379.2075 | 1 | Hydroxylation |

| GPPGESGAAGP | 28.12 | 895.4035 | 896.4122 | 0 | / |

| GPSGEPGT | 28.07 | 700.3027 | 701.3138 | 0 | / |

| SLNNQIE | 23.94 | 816.3977 | 409.2074 | 3 | / |

| GDGGPPGA | 23.76 | 626.266 | 627.2744 | 0 | / |

| GPSGDRGPR | 23.14 | 897.4417 | 898.4459 | 1 | / |

| VGAPGPA | 21.44 | 567.3016 | 568.3106 | 0 | / |

−10lgP Confidence of peptides, PTM Post-translational modification, Cleavage site Total cleavage sites of chymotrypsin, pepsin and trypsin

Fig. 4.

Antioxidant activity of synthetic peptides. a ABTS radical scavenging activity. b Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity. c Reducing power. d Ferrous ion chelating activity. The same lowercase letter indicates no significant difference in values (P > 0.05) (P1: GFPGLPGPS; P2: GVVGLPGQ; P3: GFPGADGVA; P4: GEAGPSGPA; P5: GGPQGPR; P6: GVPGPPGAV; P7: GPSGDPGK; P8: GSQGSQGPA; P9: GPAGPSGPAG; P10: GERGLPGVA)

Evaluation of cellular antioxidant activity of synthetic peptides

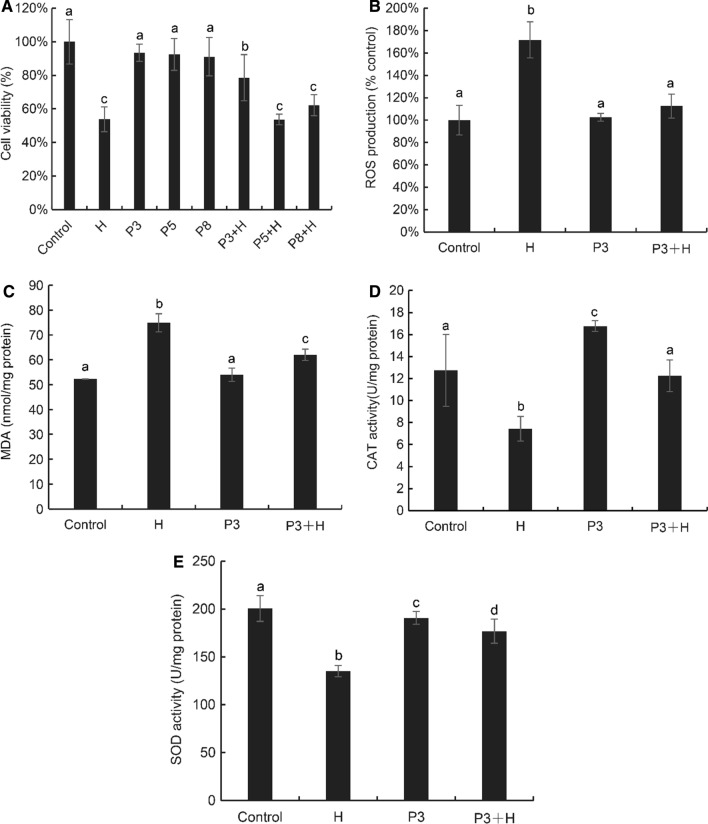

The antioxidant activity of ten peptides was determined, among which P3, P5 and P8 possessed good activity. Therefore, we paid attention to whether they can protect H2O2-induced cellular oxidative stress effectively. As shown in Fig. 5a, 1 mM H2O2 can reduced significantly (P < 0.05) the viability of Caco-2 cells to 53.80%. After treatment with P3, P5 and P8 at a concentration of 30 μg/mL for 24 h, the cell viability was above 90%, which were P3 (93.48%), P5 (92.46%), and P8 (91.04%). The results showed that the cytoprotective effect of P3 was the best, and the cell viability increased to 78.62% compared with the H2O2 group (53.80%), indicating that the cells were well protected after 30 μg/mL GFPGADGVA pretreatment for 24 h. The effect of P8 was the second with cell viability of 62.22%, but there was no significant effect of P5 treatment (P > 0.05). Therefore, GFPGADGVA (P3) was selected for subsequent determination of ROS, MDA, and antioxidant enzyme activity in Caco-2 cells.

Fig. 5.

Cell based antioxidant activity of synthetic peptides from yak bone. a Cell viability, b intracellular ROS level, c intracellular MDA content, d CAT activity, and e SOD activity in conditions with or without oxidation induced by H2O2. Values with different letters were significantly different (P < 0.05) for each assay. The same lowercase letter indicates no significant difference in values (P > 0.05) (Control: untreated cells; H: 1 mM H2O2 treated cells for 1 h; P3: 30 μg/mL GFPGADGVA treated cells; P5: 30 μg/mL GGPQGPR treated cells; P8: 30 μg/mL GSQGSQGPA treated cells; P + H: 30 μg/mL peptides pretreatment + 1 mM H2O2 treated cells)

As markers of oxidative stress in Caco-2 cells, the concentrations of ROS and MDA were detected to investigate whether increase in cell viability was related to the antioxidant activity of the peptide (Fig. 5b–c). Treatment with H2O2 increased ROS in cells (171.67%), while GFPGADGVA pretreatment reduced ROS to 112.00%. However, cells treated with GFPGADGVA alone had little effect on ROS (102.50%), suggesting that the great efficiency of GFPGADGVA to inhibit oxidative modifications of Caco-2 cells stimulated by H2O2. Oxidative stress may cause lipid peroxidation with the formation of MDA. When Caco-2 cells treated with 1 mM H2O2 for 1 h, MDA increased to 74.89 nmol/mg protein. However, GFPGADGVA treatment significantly inhibited the formation of MDA (62.06 nmol/mg protein) in cells caused by H2O2. Similarly, GFPGADGVA alone did not affect MDA concentration compared with the control group.

The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) were measured to investigate whether GFPGADGVA could affect the endogenous antioxidant system of Caco-2 cells (Fig. 5d–e). After Caco-2 cells were treated with H2O2 alone, SOD activity was 135.12 U/mg protein, which was significantly inhibited compared with the control group (200.62 U/mg protein). However, after pretreatment with GFPGADGVA, SOD activity increased significantly (P < 0.05) to 176.89 U/mg protein, indicating that GFPGADGVA has the ability to protect cells from H2O2 toxicity. Compared with the control group (12.74 U/mg protein), H2O2-induced oxidation reduced CAT activity to 7.44 U/mg protein. However, GFPGADGVA treatment alone improved CAT activity to 16.76 U/mg protein significantly (P < 0.05). The CAT of the group co-treated with GFPGADGVA and H2O2 was 12.25 U/mg protein, which was significantly higher than that of the H2O2 group (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to prepare yak bone peptides and evaluate their antioxidant activity. Collagen was extracted from yak bones in hot water at high temperature and pressure conditions to prepare gelatin. Papain and alcalase are commonly enzymes used to hydrolyze yak bone collagen and other proteins, and their hydrolysates possess good antioxidant activity (Chen et al. 2011; Li et al. 2009a, b). After enzymatic hydrolysis of yak bone protein by papain for 0.5 h, the MW distribution of hydrolysates no longer showed significant differences, which is similar to results of Gao et al. (2019). The MW distribution showed that the hydrolysis of yak bone protein by papain usually occurred in the first 0.5 h, while the content of small molecules (MW < 1 kDa) in hydrolysates generated by alcalase was higher. Low-MW peptides are more easily absorbed by the human body and exhibit greater bioavailability than unhydrolyzed proteins (Chalamaiah et al. 2018). However, antioxidant activity of hydrolysates generated by alcalase was better in this study. The activity of enzymatic hydrolysates is related to the type of enzyme, and the antioxidant activity of hydrolysates generated by alcalase fluctuates with the degree of hydrolysis (Vilailak et al. 2007).

Achieving the potential biological activity of peptides depends largely on its ability to remain intact before reaching the target. In the process of digestion, peptide bonds were cleaved through the action of enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in small peptides and free amino acids (Segura-Campos et al. 2011). Therefore, after measuring the MW distribution, it was found that the MW of the products after simulated digestion further decreased. The peptides and amino acid sequences released by digestion showed special properties, therefore, digestion is an important process of the formation and degradation of bioactive peptides, which can also lead to changes in antioxidant activity (Samaranayaka et al. 2010). The ability of a peptide to resist enzyme action is related to the amino acid composition. For example, peptides containing Pro and Hyp residues are generally resistant to degradation by digestive enzymes (Segura-Campos et al. 2011). The contents of Pro and Hyp in YBH were higher, and the ferrous ions chelating ability in simulated digestion products increased in this study, while the other three indexes decreased but were still significantly (P < 0.05) higher than unhydrolyzed proteins.

GI-YBH was separated into two parts of MW > 1 kDa and < 1 kDa using ultrafiltration, among which the part with MW < 1 kDa possessed superior antioxidant activity. Low MW peptides have higher antioxidant activity, which may be due to their ability to convert free radicals into more stable forms (Zhang et al. 2019). RP-HPLC can fractionate peptides based on hydrophobicity, and the parts with weak hydrophobicity eluted first. Girgih et al. (2015) found that the parts with strong hydrophobicity had better 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazil (DPPH) radical scavenging ability and superoxide radical scavenging activity. Therefore, F5 with the best antioxidant activity was selected for mass spectrometry identification. The composition and sequence of amino acids in a peptide have an important effect on its antioxidant activity. Gly and hydrophobic amino acids (Ala, Pro, Hyp, Tyr, etc.) enhanced the interaction between peptides and fatty acids, improve the free radical scavenging and metal chelation ability. Gly and Pro are considered to play an important role in free radical scavenging ability; acidic amino acids (Asp and Glu) can quench unpaired electrons and free radicals by providing protons (Feng et al. 2018). Li and Li (2013) studied the relationship between the properties of the C-terminal and N-terminal regions of the peptide and their antioxidant capacity, which concluded that the hydrophobicity and hydrogen bonding properties of amino acids were major reason that related antioxidant activity, and the properties of the C-terminal amino acids are more important. Trp, Tyr, Phe, Met, Leu, and Ile at the third amino acid position at the C-terminal contributed to antioxidant activity. The peptides screened in this study all contained Gly, Pro or Hyp. Differences in the peptide's antioxidant activities may be caused by molecular weight or the way Gly and other hydrophobic amino acids arranged in the sequence (Rajapakse et al. 2005a). However, the relationship between the structure of peptides and their antioxidant activity is still unclear (Feng et al. 2018). In this study, four antioxidant activities were measured at the same peptide concentration (1 mg/mL), and the peptides with superior activity in each index was selected to determine the protective effect on Caco-2 cells induced by H2O2.

At the cellular level, oxidative stress on cells can lead to metabolic dysfunction, including lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, membrane rupture, and DNA damage. The synthetic peptides had a certain inhibitory effect on cell growth, and the survival rate of Caco-2 cells treated with P3, P5 and P8 at 30 μg/mL was above 90%. The oxidative stress induction of H2O2 made cells produce excessive ROS. In this process, excessive generation of ROS will attack cell tissues, causing cell membrane damage or cell necrosis. The changes in cell membrane permeability of Caco-2 caused by H2O2 may be due to the destruction of the paracellular junction complexes caused by tyrosine phosphorylation of membrane proteins (Wang et al. 2016; Wijeratne et al. 2005). However, the effect of H2O2 on Caco-2 cells was dependent both on time and concentration. In this study, 1 mM H2O2 treatment of Caco-2 cells for 1 h can reduce the cell viability significantly to 53.80% of the control group, so as to construct Caco-2 cells with H2O2-induced oxidative stress model (Liang et al. 2017). After 24 h of GFPGADGVA pretreatment, the cell viability increased to 78.62%, which was significantly higher than that of H (1 mM H2O2 treated cells for 1 h), P5 + H (30 μg/mL P5 pretreatment + 1 mM H2O2 treated cells) and P8 + H (30 μg/mL P8 + 1 mM H2O2 treated cells) groups. Compared with GGPQGPR (P5) and GSQGSQGPA (P8), the content of hydrophobic amino acids (Phe, Ala, Val) in GFPGADGVA was higher, and Asp is acidic amino acid, which is helpful to improve the antioxidant activity. The quenching of free radicals by collagen peptides may be its main antioxidant mechanism, mainly due to the presence of amino acids such as Pro, Ala, Val and Leu (Giménez et al. 2009).

The induction of H2O2 lead to the production of excessive ROS in cells, which attack the polyunsaturated fatty acids in the biofilm, causing the lipid peroxidation to form MDA. SOD can catalyze the disproportionation of superoxide anions to generate H2O2 and O2, which is an important antioxidant enzyme; CAT is an important enzyme system to remove hydrogen peroxide, and can convert H2O2 into water (Liang et al. 2017). After pretreatment with GFPGADGVA, the content of intracellular ROS and MDA decreased, and the activities of SOD and CAT increased significantly (P < 0.05). Antioxidant peptides can remove ROS in oxidation-damaged cells, or activate the antioxidant system in pre-protected cells to up-regulate the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes, so as to reduce the oxidation level in injured cells and protect cells from H2O2-induced oxidative damage. In addition, the decrease in MDA content indicated that GFPGADGVA protected the cell membrane from oxidative damage and inhibited lipid peroxidation, thereby preventing ROS from entering the cell (Cheng et al. 2006). GFPGADGVA is mainly composed of hydrophobic amino acids and Gly, which is highly hydrophobic and may have certain interactions with fatty acids. Hydrogen atoms in the side chain of Gly are potential targets for free radicals that can quench unpaired electrons or free radicals by supporting protons (Wu et al. 2015). The decrease in SOD activity may be caused by the interaction between H2O2 and Cu2+ in the SOD. The generated hydroxyl radicals and copper radicals may result in the degeneration of SOD proteins (Hadgson and Fridovich 1975). Therefore, the protective effect of GFPGADGVA on SOD may be due to chelating excess Cu2+ to prevent the metal from reacting with H2O2.The Asp contained in GFPGADGVA can interact with metal ions through its charged residues to inactivate the oxidation activity of metal ions (Saiga et al. 2003). The aromatic amino acid Phe was present in the structure of GFPGADGVA, which provided protons to electron-deficient radicals while maintaining their stability through resonance structures (Rajapakse et al. 2005b). The hydrophobic amino acids Val and Ala at the C-terminal can also enhance the antioxidant capacity. Himaya et al. (2012) extracted a peptide (Gly-Gly-Phe-Asp-Met-Gly) from Japanese flounder (Palatichtys olivaceus) skin gelatin, which can effectively remove intracellular ROS and up-regulate the expression of SOD and CAT in cells.

In conclusion, the protective effect of GFPGADGVA on Caco-2 cells induced by H2O2 may be due to two aspects. On the one hand, peptides have radical scavenging activity, which can inhibit free radical-mediated oxidation; On the other hand, peptides can effectively remove the damage of oxidative stress by coordinating intracellular antioxidant enzymes, thus preventing oxidative stress (Guo et al. 2014).

Conclusion

Yak bone hydrolysates possessed strong antioxidant activity, but the antioxidant activity decreased after simulated gastrointestinal digestion in vitro. GI-YBH was separated by ultrafiltration and RP-HPLC, and 61 peptides with MW < 1 kDa were identified from the F5 components. Among them, Gly-Phe-Hyp-Gly-Ala-Asp-Gly-Val-Ala possessed good cytoprotective effect, which can reduce the content of ROS and MDA in cells and improve the activity of SOD and CAT enzymes. This peptide derived from yak bone hydrolysates may be a potential protective agent or food additive against oxidative stress.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (award number 2017YFD0400201).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest related to this article.

Human and animal rights

The research did not include any human subjects and animal experiments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agrawal H, Joshi R, Gupta M. Isolation, purification and characterization of antioxidative peptide of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) protein hydrolysate. Food Chem. 2016;204:365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.02.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalamaiah M, Hemalatha R, Jyothirmayi T. Fish protein hydrolysates: proximate composition, amino acid composition, antioxidant activities and applications: a review. Food Chem. 2012;135:3020–3038. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalamaiah M, Yu W, Wu J. Immunomodulatory and anticancer protein hydrolysates (peptides) from food proteins: a review. Food Chem. 2018;245:205–222. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.10.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Tsai ML, Huang J, Chen R. In vitro antioxidant activities of low-molecular-weight polysaccharides with various functional groups. J Agr Food Chem. 2009;57:2699–2704. doi: 10.1021/jf804010w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Cheng L, Xu H, Song H, Lv Y, Yang C, Sun N. Functions of different yak bone peptides. Int J Food Prop. 2011;14:1136–1141. doi: 10.1080/10942911003592753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Wang Z, Xu S. Antioxidant properties of wheat germ protein hydrolysates evaluated in vitro. J Cent South Univ T. 2006;13:160–165. doi: 10.1007/s11771-006-0149-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devi S, Kumar N, Kapila S, Mada SB, Reddi S, Vij R, Kapila R. Buffalo casein derived peptide can alleviates H2O2 induced cellular damage and necrosis in fibroblast cells. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2017;69:485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Ruan G, Jin F, Xu J, Wang F. Purification, identification, and synthesis of five novel antioxidant peptides from Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima Blume) protein hydrolysates. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2018;92:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Hong H, Zhang C, Wang K, Zhang B, Han QA, Luo Y. Immunomodulatory effects of collagen hydrolysates from yak (Bos grunniens) bone on cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression in BALB/c mice. J Funct Foods. 2019;60:103420. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giménez B, Alemán A, Montero P, Gómez-Guillén MC. Antioxidant and functional properties of gelatin hydrolysates obtained from skin of sole and squid. Food Chem. 2009;114:976–983. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.10.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Girgih AT, He R, Hasan FM, Udenigwe CC, Gill TA, Aluko RE. Evaluation of the in vitro antioxidant properties of a cod (Gadus morhua) protein hydrolysate and peptide fractions. Food Chem. 2015;173:652–659. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Zhang T, Jiang B, Miao M, Mu W. The effects of an antioxidative pentapeptide derived from chickpea protein hydrolysates on oxidative stress in Caco-2 and HT-29 cell lines. J Funct Foods. 2014;7:719–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2013.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hadgson EK, Fridovich I. The interaction of bovine erythrocyte superoxide dismutase with hydrogen peroxide: inactivation of the inzyme. Biochemistry-US. 1975;14:5294–5299. doi: 10.1021/bi00695a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himaya SWA, Ryu B, Ngo DH, Kim SK. Peptide isolated from Japanese flounder skin gelatin protects against cellular oxidative damage. J Agr Food Chem. 2012;60:9112–9119. doi: 10.1021/jf302161m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeevithan E, Bao B, Bu Y, Zhou Y, Zhao Q, Wu W. Type II collagen and gelatin from silvertip shark (Carcharhinus albimarginatus) cartilage: Isolation, purification, physicochemical and antioxidant properties. Mar Drugs. 2014;12:3852–3873. doi: 10.3390/md12073852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Kim YT, Byun HG, Nam KS, Joo DS, Shahidi F. Isolation and characterization of antioxidative peptides from gelatin hydrolysate of Alaska pollack skin. J Agr Food Chem. 2001;49:1984–1989. doi: 10.1021/jf000494j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar NSS, Nazeer RA, Jaiganesh R. Purification and identification of antioxidant peptides from the skin protein hydrolysate of two marine fishes, horse mackerel (Magalaspis cordyla) and croaker (Otolithes ruber) Amino Acids. 2012;42:1641–1649. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0858-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassoued I, Mora L, Nasri R, Jridi M, Toldrá F, Aristoy MC, Nasri M. Characterization and comparative assessment of antioxidant and ACE inhibitory activities of thornback ray gelatin hydrolysates. J Funct Foods. 2015;13:225–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.12.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Li B. Characterization of structure–antioxidant activity relationship of peptides in free radical systems using QSAR models: Key sequence positions and their amino acid properties. J Theor Biol. 2013;318:29–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Jia D, Yao K. Amino acid composition and functional properties of collagen polypeptide from yak (Bos grunniens) bone. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2009;42:945–949. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2008.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Jia D, Yao K. Amino acid composition and functional properties of collagen polypeptide from yak (Bos grunniens) bone. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2009;42:945–949. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2008.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang R, Zhang Z, Lin S. Effects of pulsed electric field on intracellular antioxidant activity and antioxidant enzyme regulating capacities of pine nut (Pinus koraiensis) peptide QDHCH in HepG2 cells. Food Chem. 2017;237:793–802. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.05.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajapakse N, Mendis E, Byun HG, Kim SK. Purification and in vitro antioxidative effects of giant squid muscle peptides on free radical-mediated oxidative systems. J Nutr Biochem. 2005;16:562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajapakse N, Mendis E, Jung WK, Je JY, Kim SK. Purification of a radical scavenging peptide from fermented mussel sauce and its antioxidant properties. Food Res Int. 2005;38:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2004.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saiga AI, Tanabe S, Nishimura T. Antioxidant activity of peptides obtained from porcine myofibrillar proteins by protease treatment. J Agr Food Chem. 2003;51:3661–3667. doi: 10.1021/jf021156g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakanaka S, Tachibana Y. Active oxygen scavenging activity of egg-yolk protein hydrolysates and their effects on lipid oxidation in beef and tuna homogenates. Food Chem. 2006;95:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.11.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samaranayaka AG, Kitts DD, Li-Chan EC. Antioxidative and angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibitory potential of a Pacific hake (Merluccius productus) fish protein hydrolysate subjected to simulated gastrointestinal digestion and Caco-2 cell permeation. J Agr Food Chem. 2010;58(3):1535–1542. doi: 10.1021/jf9033199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura-Campos M, Chel-Guerrero L, Betancur-Ancona D, Hernandez-Escalante VM. Bioavailability of bioactive peptides. Food Rev Int. 2011;27:213–226. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2011.563395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vilailak K, Soottawat B, Duangporn K, Fereidoon S. Antioxidative activity and functional properties of protein hydrolysate of yellow Stripe trevally (Selaroides leptolepis) as influenced by the degree of hydrolysis and enzyme type. Food Chem. 2007;102:1317–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Ding L, Yu Z, Zhang T, Ma S, Liu J. Intracellular ROS scavenging and antioxidant enzyme regulating capacities of corn gluten meal-derived antioxidant peptides in HepG2 cells. Food Res Int. 2016;90:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijeratne SS, Cuppett SL, Schlegel V. Hydrogen peroxide induced oxidative stress damage and antioxidant enzyme response in Caco-2 human colon cells. J Agric and Food Chem. 2005;53:8768–8774. doi: 10.1021/jf0512003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R, Wu C, Liu D, Yang X, Huang J, Zhang J, Li H. Overview of antioxidant peptides derived from marine resources: the sources, characteristic, purification, and evaluation methods. Appl Biochem Biotech. 2015;176:1815–1833. doi: 10.1007/s12010-015-1689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie N, Liu S, Wang C, Li B. Stability of casein antioxidant peptide fractions during in vitro digestion/Caco-2 cell model: characteristics of the resistant peptides. Eur Food Res Technol. 2014;239:577–586. doi: 10.1007/s00217-014-2253-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young IS, Woodside JV. Antioxidants in health and disease. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:176–186. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.3.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Qu J, Thakur K, Zhang J, Mocan A, Wei Z. Purification and identification of an antioxidative peptide from peony (Paeonia suffruticosa Andr.) seed dreg. Food Chem. 2019;285:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.01.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Xu Z, Chen A, You X, Zhao Y, He W, Yang S. Identification of meat from yak and cattle using SNP markers with integrated allele-specific polymerase chain reaction–capillary electrophoresis method. Meat Sci. 2019;148:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Y, Sun L, Zhao X, Wang J, Hou H, Li B. Antioxidant and melanogenesis-inhibitory activities of collagen peptide from jellyfish (Rhopilema esculentum) J Sci Food Agr. 2009;89:1722–1727. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]