Abstract

Scaled up planning and implementation of nature-based solutions requires better understanding of broad characteristics (typologies) of the current governance and financing landscape, collaborative approaches amidst local complexities, and factors of scalability. An inventory was compiled of water-related ecological infrastructure intervention projects in two river systems in South Africa, incorporating actor, environmental, social, and financial dimensions and benefits. Qualitative participatory analysis revealed eight typologies. Post-hoc classification analysis determined similarities and/or unique characteristics of seven quantitative typologies. Key characterising factors included the complexity/size of financial flows, complexity of partnership/governance arrangements, mandates/goals of actors, type of ecological infrastructure, trade-offs in investment in ecological/built infrastructure, and the model used for social benefits. Identified scalable typologies offer structures suited to increased investment, with other typologies offering specialised local value. A range of ecological infrastructure intervention typologies with differing biophysical and socioeconomic outcomes provide choices for investors with specific goals, and benefits to landscape actors.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13280-021-01531-z.

Keywords: Catchment ecology, Ecological infrastructure, Local communities, Partnerships, Typologies of nature-based solutions, Water sector

Introduction

Anthropogenic influences now dominate catchments globally as large tracts of land are converted to other land uses and novel disturbances are introduced (WWAP/UN-Water 2018). Climate change is shifting rainfall patterns and increasing extreme weather risks, and invasive alien species are altering ecosystems and water flows (IUCN 2017). Simultaneously, water demands are increasing due to economic development and population growth (Boretti and Rosa 2019), resulting in significant water security risks. This situation applies to many water scarce regions and is a critical issue for sustainable development and well-being in semi-arid southern Africa, where this study is located.

In South Africa, water supply relies heavily on built infrastructure for storage, transfer and purification at a pre-defined level of assurance of supply. Demand is rising, yet most cost-effective built infrastructure options have been exploited (van Rooyen and Versfeld 2010). Costs are rising to assure water quality, especially for drinking water and irrigation, thus challenging water service providers (Cullis et al. 2019). We must adopt solutions that harness the natural environment and its delivery of ecosystem services to complement traditional built infrastructure. Known as Nature-based Solutions (NBS, Cohen-Shacham et al. 2016), approaches include ecosystem-based adaptation, ecological restoration, and interventions to strengthen ecological infrastructure (EI). To be effective, NBS need to be implemented at a scale that adequately addresses ecosystem degradation (Perring et al. 2018; Cohen-Shacham et al. 2019). Restoring functional EI in catchments to supply water related ecosystem services at scale, while simultaneously providing sustainable social and developmental benefits, is a widely supported NBS in South Africa (Angelstam et al. 2017; Cumming et al. 2017).

EI comprises “naturally functioning ecosystems that produce and deliver valuable services to people, …, which together form a network of interconnected structural elements in the landscape” (SANBI 2014). We focus on EI interventions aimed at increasing water yields and quality in degraded mountain catchments, rivers and wetlands. While other EI interventions are implemented in South Africa (SANBI 2014), the clearing of invasive alien plants (IAPs) in catchments has a long history (van Wilgen et al. 2016) and constitutes the bulk of investment in EI, primarily through the Natural Resources Management Programme of the Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA NRM, Box S1). Research shows that the water use of IAPs in South African catchments can reach 15% of water demand (Cullis et al. 2007). Marginal costs of EI interventions compare favourably to those of built infrastructure (DWA 2010), and the social benefits of job creation and skills development for the poor are considerable (Giordano et al. 2012).

Nevertheless, the value and size of EI investments in South Africa is small relative to the need (van Wilgen and Wannenburgh 2016) despite the search for new investments (The Nature Conservancy 2019). NBS worldwide are inadequately scaled to achieve the desired impact (Perring et al. 2018). A common understanding or conceptual framework of what scaling means for NBS, and possible trade-offs, is lacking (Fastenrath et al. 2020). Barriers to scaling of NBS include complex combinations of inadequate human and financial resources, insufficient knowledge and technical know-how, divergent motivations and goals, weak institutional capacities and governance structures, insufficient coordination and cooperation, and inadequate policies, laws and regulations (Murcia et al. 2016; Ershad Sarabi et al. 2019). A useful first step in developing a conceptual framework for the scaling of NBS is to better understand broad characteristics (typologies) of the current governance and financing landscape and collaborative approaches amidst local complexities.

To achieve coordinated and efficient EI investment across varying multi-use catchment landscapes, we need to strengthen governance modes across multiple scales of management and jurisdiction (Ros-Tonen et al. 2018) and multiple actors (Diaz-Kope and Miller-Stevens 2015). A starting point is to generate broad yet relevant representations (typologies) of the diversity of existing EI implementation approaches within a region that depict their governance/partnership models and financial arrangements. Typologies would help to identify actors involved and appropriate interventions per site, relative to project objectives. Within the collaborative watershed management field, typology analysis has identified key variations between diverse partnership approaches in terms of their composition and accomplishments (Moore and Koontz 2003) and their governance structures (Diaz-Kope and Miller-Stevens 2015). These studies emphasise government-directed, citizen-directed and hybrid collaborative partnerships.

Typology analysis has been used to better understand the major project features of rural and urban river restoration projects in France (Zingraff-Hamed et al. 2017). The urban typologies were enriched by the integration of ecological and social goals of river restoration in cities. This is important for a conceptual framework for NBS scaling (Cohen-Shacham et al. 2019). Of relevance to the Global South is the study by Coppus et al. (2019) who developed typologies of land restoration projects in Latin America and the Caribbean. The amount and source of funding received for the projects constituted two of the four main defining variables for the three identified typologies. Complex socio-economic settings must be integrated into the design and implementation of restoration projects at larger scales. There remains a gap in understanding how different approaches to EI interventions (and, more broadly, NBS) in degraded landscapes play out with respect to an integrated systems-based view on environmental goals, socio-economic goals, governance, collaborative partnership arrangements, and sizes and sources of funding. These elements all require consideration within a conceptual framework for the scaling of NBS.

In this study, we apply two complementary approaches to typology identification to explore how different collaborative governance models and financial arrangements play out in existing EI intervention typologies in complex catchment landscapes. We also provide initial insights into the potential of the qualitatively derived typologies for the scaling of EI interventions to achieve greater impact, and thus contribute towards the development of a conceptual framework for the scaling of NBS. Knowledge co-production and joint sense making with relevant landscape actors were key to this process (Giordano et al. 2020). First, we collate an inventory of existing water related EI interventions. Second, we test an approach involving qualitative typology identification combined with joint sense making with stakeholders at the funder-implementer interface to address the question ‘What EI intervention types can be found in catchment landscapes as informed by the EI intervention inventory and expert knowledge?’ Third, we enhance the qualitative study with a quantitative multivariate statistical analysis of the inventory data for further clarity on typology classification and the variables that best explain these typologies. Here, we ask ‘Do the quantitatively identified typologies agree with the qualitatively identified typologies, and, if not, are there other factors of importance?’ Fourth, we develop an initial understanding of the dimensions that could be considered when striving towards scaling and greater impact, asking the question ‘Which typologies could be scaled to large areas and many different contexts, considering their governance and financial management structures and modus operandi?’

While we focus on one form of NBS, namely water-related EI intervention projects, we argue that our method can be applied to other types of NBS and in other complex catchment landscapes.

Scaling of NBS

Scale effects on governance have been linked to issues such as cross-scale interactions, mismatch between scales of social organisation and biophysical resource management, and the neglect of plurality (Cash et al. 2006). If inadequately considered in policy and action, these issues can lead to poor governance outcomes and unintended trade-offs. In adaptive governance, emphasis is placed on matching scales and linking levels to improve governance processes and outcomes (Termeer et al. 2010). Scale can be defined in many ways (Veldkamp et al. 2011). Gibson et al. (2000) define “scale” as the spatial, temporal, quantitative, or analytical dimensions used to measure and study any phenomenon, and “levels” as the units of analysis that are located at different positions on a scale”. Building on this, several different elements of scales were identified by Cash et al. (2006) and used by Fastenrath et al. (2020) in the context of NBS, namely, spatial, temporal, jurisdictional, institutional, networks, management and knowledge scales.

Scaling strategies (Moore et al. 2015), also termed amplification processes (Lam et al. 2020), have been advanced in the research areas of sustainability transitions, resilience, and social innovations (Lam et al. 2020) and often discussed in the context of sustainability transformation and transformative change. The focus is on place-based innovations that provide local solutions and innovations to global issues. Under appropriate conditions they gain enough momentum and/or coalesce to drive a shift to more sustainable development pathways with increased regional and global impact (Lam et al. 2020).

Scaling strategies have several dimensions, but are commonly grouped into three core categories (across diverse fields of study). While scholars use a variety of definitions, and no clear definition is yet available for scaling of NBS (Fastenrath et al. 2020), we characterise the three categories of scaling as follows, drawing on Moore et al. (2015) and Lam et al. (2020):

Scaling out: involves processes such as replication, spreading, and adaptation of initiatives in different (commonly geographical) contexts. The idea is to reproduce and adapt the same initiative to new contexts without compromising core principles and the integrity of the initiative. Greater impact is achieved through greater numbers, involving or reaching more people or communities and/or covering more and larger spatial areas. Given the aims of this study, we were primarily concerned with this type of scaling.

Scaling up: achieving impact through influencing higher levels of decision making, by focusing on changing policies and laws, or addressing root causes through institutional changes. It sometimes also referred to as the process of embedding into existing institutional, legislative and policy structures.

Scaling deep: refers to efforts of changing relationships, values, beliefs and perspectives (“hearts and minds”) so that dominant practices and structures can be overcome. Deep scaling has been associated with processes of learning and knowledge sharing.

When discussing scaling and scalability in the context of NBS we note that most NBS need to be implemented over larger spatial scales, e.g. river basins, to have meaningful impact. The IUCN has made this characteristic one of the eight NBS principles. It highlights that “even when an NBS is implemented at a specific site level…., it is important to consider the wider landscape-scale context and consequences, aiming at upscaling where appropriate.” (Cohen-Shacham et al. 2019, p. 24).

We propose that scaling of NBS also requires an understanding of how site-specific initiatives of pluralistic patchworks of various governance and management constellations can combine to a larger whole that maximizes the impact of each intervention. This can bring about greater landscape impact for these solutions to adequately address societal challenges such as water security. We are, therefore, not only interested in the scaling of a single initiative, but further look at how existing typologies may complement each other, in existing and new catchment contexts to create the necessary landscape wide impact (Aronson et al 2017). Understanding the characteristics of typologies and the conditions under which they can function provides important insights into scaling, i.e. identify those that could be replicated in other catchments, those that can be used in a complementary manner at smaller scale to address specific needs, as well as obtaining additional knowledge on their joint landscape impact or lack thereof.

Materials and methods

Study site and design

The study was conducted in the upper and middle reaches of two adjacent river systems of the Western Cape Province, South Africa: the Berg River and the Breede River (and its tributary the Riviersonderend River) (Fig. 1). These naturally distinct river systems are hydrologically connected through inter-basin transfers in their upper catchments. Further information on this system is provided in Appendix S1. The delineation of appropriate study boundaries was achieved iteratively. After initially focusing on three hydrologically modelled sub-catchments, we broadened the area to include adjacent sub-catchments encompassing farms, communities and towns from which project beneficiaries (work teams) were recruited in the projects. The spatial boundaries of the study were formalized by identifying relevant quaternary catchments (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Map of the study area, showing the position within South Africa (inset) and indicating the upper parts of the secondary (white) catchments, as well as the quaternary (yellow) catchments considered in the inventory

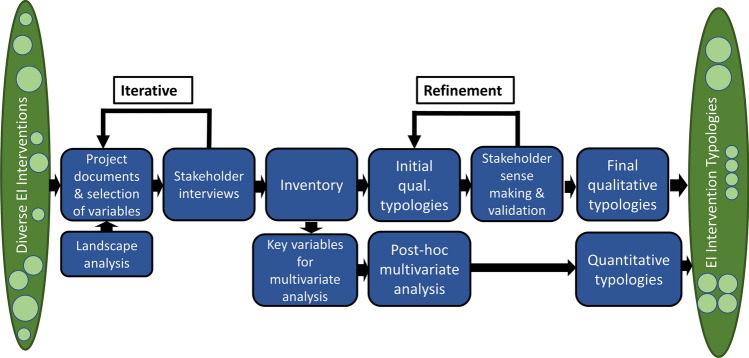

We used a two-pronged complementary mixed methods approach (combined qualitative and quantitative data) followed by multivariate statistical analysis (Fig. 2). For the construction of the inventory and first set of qualitative typologies we used an embedded design where quantitative data were included to answer certain research questions within a largely qualitative methodology. Second, a post hoc multivariate (clustering) statistical analysis was conducted on the descriptive variables from the inventory. This analysis served as a test of the first set of qualitative typologies. The overarching design was thus an exploratory sequential design (Cresswell et al. 2003).

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of the process adopted to determine qualitative and quantitative ecological infrastructure intervention typologies (following Alvarez et al. 2014)

Development of the EI intervention inventory

EI interventions are for this study defined as actions to enhance certain ecosystem services in a spectrum of landscapes (from natural to transformed), informed by an understanding of ecology. We defined actions as including artificial wetlands, permeable pavements, alien clearing, wetland revegetation, and gabions and weirs to halt erosion.

We compiled a list of projects that met the definition of an EI intervention, and that started in 2013 or later (capturing more current approaches), with at least one completed implementation year. We drew on personal knowledge of projects and actors to collate an initial list. A snowballing method to identify further projects was then employed. Interviews were halted when it became clear that saturation was reached in terms of the emerging EI intervention approaches. While sampling was not seen to be quantitatively representative, it was sufficient to capture the various typologies qualitatively. A total of 27 projects were included in the inventory (Table S1).

Interviewees positioned at the funder-implementer interface (i.e. professional persons within organizations receiving project funding and involved in the planning, decision making and effective implementation of projects according to contracts) were selected using purposive sampling. We did not interview “implementing agents” (entities responsible for managing contractual processes), “contractors” (successful bidders who perform the work using teams of workers that they source and manage), or members of the “work teams” (from trained laborers to highly skilled workers). The interviewees represented the DEA NRM Programme, local government, Provincial/State government departments, Provincial/State conservation bodies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), government catchment-level bodies for water resources management, and employees of private landowners or conservancies. Seventeen interviews were conducted covering the 27 projects. The full population of projects is unknown due to the absence of a formal process to list such initiatives; however, the major role players and projects are well known within the communities of practice and we estimate that we captured the majority of projects (> 90%).

Face-to-face interviews were semi-structured with open-ended questions following an interview guideline (Table 1). Notes were taken but the interviews were not recorded or transcribed. The questions and level of detail were handled flexibly depending on the nature of the projects being discussed and available time. The duration of each interview ranged between about 30 and 90 min.

Table 1.

Structure of the EI intervention inventory indicating broad themes (headings) and associated variables

| Project information |

|---|

| Quaternary catchment numbers |

| Catchment |

| Project name |

| Lead organisation |

| Project manager and contacts |

| Partner organisations |

| Project years (between 2014 and 2018) |

| Land ownership |

| Local Municipality |

| Nearest town |

| Towns where labour is sourced |

| Biophysical characteristics of intervention sites |

| Name of river/wetland |

| Vegetation type |

| Land uses/cover |

| Mean annual precipitation (mm) |

| Mean annual temperature (°C) |

| Key climate risks |

| Water-related ecological and built infrastructure types and interventions |

| EI type |

| EI intervention |

| Area of intervention (ha) |

| Key built water infrastructure in that part of the river system |

| Financial and organisational characteristics |

| Partnership model |

| Main source of funding |

| Other sources of funding |

| Private landowners’ contribution |

| Number of funding sources |

| Annual budget |

| Goals/mandate of receiving and responsible organisation |

| Nature of receiving and responsible organisation |

| Complexity of partnerships |

| Project benefits: water, risk reduction, social, economic |

| Benefits: water-related |

| Benefits: climate risk reduction |

| Benefits: downstream water users |

| Benefits (social): number of people employed |

| Benefits (social): towns of origin of workers |

| Benefits (social): job security (duration, predictability) |

| Benefits (social): skills required & level of training |

| Benefits (economic): business/markets |

| Diversity of benefits |

A database of water related EI intervention projects was constructed based on broad pre-determined themes and variables (Table 1). The themes covered environmental (biophysical), social, financial and organisational dimensions and benefits (similar to the broad classes used by Coppus et al. 2019). Variables within the themes were chosen to describe structural and functional diversity of interventions currently encountered. It was populated using the written interview notes and additional project data files and reports provided by interviewees. Some biophysical information was obtained from recognised scientific sources. A minority of variable fields were populated with quantitative data, e.g. annual project budget or number of people employed annually. As inventory development proceeded, we converted these fields into categorical data denoting size class or range.

Development of qualitative EI intervention typologies

To capture the main governance and finance modalities the initial conceptual typology structure was developed inductively by aggregating projects through broad flows of funding and implementation within the project from primary funder to local direct beneficiaries (work teams) (Fig. 3A). We also considered the number and nature of co-funders, the nature of the receiving and responsible (lead) organisations (Table S2), the approach to engaging implementing agents, contractors and workers, and the number and nature of supporting partner organisations. Other factors included the EI type(s) (indicated in the “stars” in Fig. 3), whether the intervention occurred on public or private land, the role of private landowners, size of annual budget (in broad categories) and level of job security for employed field workers (indicated using colour combinations in the “work teams” block in Fig. 3). Using the information gathered in the inventory, a draft set of typologies was developed. At this stage, the analysis remained subjective, being based on the researchers’ interpretation of patterns seen in the data.

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagrams of all qualitative water related EI intervention typologies in the Berg River and Breede River catchments, South Africa. Larger black “funder” fields indicate relative contribution to the annual budget in broad terms. Arrows indicate the flow of funding. The “work teams” field also shows whether jobs are more short term—months (orange), more medium term—contracts up to 3 years (orange-green gradient), or semi-permanent to permanent (green). Typology names, typology abbreviations and other abbreviations are given in the associated table below

To investigate the complexity and diversity of governance and finance arrangements of EI interventions, we worked closely with key stakeholders. A stakeholder workshop served as a platform where stakeholders were invited to verify, critique, and refine the emerging set of typologies and to jointly identify the scaling potential of each typology. The 24 participants represented local, provincial, and national government (two-thirds), academia (one quarter) and NGOs (Table S3). They also represented a range of projects and roles (implementer, contractor, funder).

After presenting the purpose, methodologies, and draft qualitative typologies, participants engaged in interactive “world café” style group work (Prewitt 2011) using three group rotations. The purpose was to discuss each typology in detail and to either critique and refine or verify the roles and relations of the actors and the structure of financial flows. The discussions were aided by visual presentation of the schematic diagrams for each typology (Fig. 3B-I).

Assessment of the potential for scaling for each qualitative typology

Workshop participants then jointly identified the scaling potential of each typology. By this we meant: (a) existing financial management structures and practices are geared towards large budgets and there is scope to manage significantly larger budgets; (b) governance and financial management structures exist across the country; and (c) the typology, in terms of its prevalent water-related EI interventions, can have a high impact across large spatial scales where restoration is greatly needed. To assist the stakeholders in their decision making we asked them “If you were given a large sum of money, which of these typologies would you use for the implementation of EI interventions across the country?” The criteria were based on known major barriers to scaling EI programmes in South Africa and other similar developing countries (e.g. Murcia et al. 2016). The discussion was guided by the schematic diagrams (Fig. 3B-I). Finally, key points of discussion regarding some of the perceived barriers to scaling for different typologies were noted. The assessment of scaling potential was confined to the qualitative research process. Future research could strengthen and extend the quantitative analysis by employing additional statistical methods to clarify the nature and possible application of “scalability” in practice.

Quantitative analysis of EI intervention typologies

Fifty-eight variables in the inventory were converted into categorical and binary data and subjected to Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components (HCPC) (Tables S4A & S4B). The HCPC combines Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) with Hierarchical Clustering. The MCA step serves to analyse the multidimensional categorical variables and their relationships and to pre-process the data so that a subsequent hierarchical cluster analysis can be performed on the categorical data. More detail on the analysis is provided in Appendix S1. Figure S1 presents the scree plot of the MCA. The resulting dendrogram (Fig. S2) was cut to yield seven clusters. The significance of the variables in explaining the clustering was assessed for all clusters combined, and for each of the seven individual clusters (typologies) (Fig. S3).

Results

Qualitative EI intervention typologies

Eight draft EI intervention typologies were identified and represented schematically (Fig. 3B-I). Some typologies were divided into two sub-groups representing differing approaches between two divisions within the same lead organisation. In Table S2 we describe in detail the names and abbreviations of stakeholder institutions shown in Fig. 3, the institutional type, spatial reach, and the roles and mandates.

Key distinguishing characteristics between typologies were identified as:

The complexity and size of financial flows;

The financial participation of private landowners;

The complexity of partnership and governance arrangements;

The mandates and objectives of participants at each step – especially those of the lead organisation;

The nature of the EI being restored and rehabilitated;

Combined use of ecological and built infrastructure interventions;

The model used for employment and other social benefits.

We note that the original Working for Water programme (van Wilgen et al. 1998) does not emerge as a current typology although it was the blueprint for such efforts. It cuts across most of the typologies and remains strong as a funder (making use of implementing agents) and partner in many current projects.

After several refinements, the eight draft typologies were accepted by the stakeholders as representing the EI Project “space” in the catchments. Refinements were limited to minor corrections to the funding and implementation structures and partners. The important role of Local Municipalities was highlighted, and additional important role players (e.g. Fire Protection Associations) and sources of co-funding were added. The final eight qualitative typologies are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of the final eight qualitative water related EI intervention typologies in the Berg River and Breede River catchments, South Africa

| Variable | Typology | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Name | DEA NRM Specialisedd | Local Government | Provincial/State Government (Environment Dept) | Provincial/State Government (Agriculture Dept)e | Water Sector | Collaborative Agriculture and Waterf | Environmental NGO | Landowner/Conservancy |

| Code | S | LG | EPSG | APSG | WS | CAW | ENGO | LC |

| Projects |

S.1 DEA_WoF_Berg (i) S.2 DEA_WoF_Riviers (i) |

LG.1 CWDM_BRD LG.2 CoCT_Wemm LG.3 SLM_Wemm LG.4 CWDM_Pniel LG.5 BVLM_Mol LG.6 BVLM_Kwagg LG.7 SLM_Purg LG.8 SLM_MontR |

EPSG.1 CN_Berg (i) EPSG.2 DEADP_Berg (ii) EPSG.3 CN_Breede (i) EPSG.4 CN_Riviers (i) EPSG.5 DEADP_Breede (ii) EPSG.6 DEADP_WSFWS (ii) |

APSG.1 DoA_Riviers (i) |

WS.1 WUA/CMA_UpBreede WS.2 WUA/CMA_CentBreede WS.3 ZWUA_Vyeboom WS.4 ZWUA_Zonderend |

CAW.1 LandCare_Breede CAW.2 WWF_Breede CAW.3 LandCare_Holsloot |

ENGO.1 TWT_Berg |

LC.1 Boschendal (ii) LC.2 GSC_Berg (i) |

| Lead organisation/actors | Working on Fire (WoF) (i) & Working for Wetlands (WfWet) (ii) | District, Local and Metropolitan Municipalities |

Two sub-groups in DEA&DP: (i) Provincial conservation body (CapeNature); (ii) Directorate Pollution Management |

Two sub-groups in DoA: (i) Sustainable Resource Management; (ii) Original LandCare-led approach |

Various Water User Associations (WUAs) and the Breede-Gouritz Catchment Management Agency (BGCMA) | Various Water User Associations (WUAs) and the Breede-Gouritz Catchment Management Agency (BGCMA) | Environmental NGO | Private landowners in two sub-groups: (i) Conservancy; (ii) individual farm |

| Funding source (main) | Entirely National Treasury through DEA NRM | Primarily National Treasury through DEA NRM Working for Water (WfW) |

CapeNature (i): National Treasury through DEA NRM (WfW) and DEA&DP; Pollution Management (ii): DEA&DP with landowner contributions |

Sustainable Resource Management (SRM) (i): National Disaster Risk Reduction, LandCare, and provincial grant to DoA; LandCare (ii): National LandCare and Catchment Management Agency | National Treasury through DEA NRM (WfW) and water user levies administered by the BGCMA | National Treasury through DEA NRM (WfW) and water user levies administered by the BGCMA | Primarily National Treasury through the DEA NRM (WfW) | Conservancy (i): primarily National Treasury through DEA NRM (WfW); Farm (ii): Self-funded |

| Land owner | Public & private | Public |

CapeNature: Public land (conserved); Pollution Mgt: public & private |

SRM: public, linked to agricultural land; LandCare: Public & private linked to agricultural land | Public & private | Public & private linked to agricultural land | Public & private | Private |

| EI Type | Areas difficult to access: high-altitude catchments (WoF) and wetlands (WfWet) | Conserved mountain catchments and riparian zones |

CapeNature: conserved mountain catchments and riparian zones; Pollution Mgt: mainly riparian zones (rehabilitation) |

SRM: Riparian zones (river stabilisation, use of engineered structures e.g. groynes); LandCare: catchments and riparian zones linked to agricultural land | Riparian zones and wetlands | Riparian zones and wetlands linked to agricultural land | Mountain catchments and riparian zones | Catchments (uncultivated land) and riparian zones linked to agricultural land |

| Budget | Costs are higher per unit area IAPs cleared than for non-specialised EI interventions | Standard as per the DEA NRM programme | Standard as per the DEA NRM programme | SRM: Costs are very high in comparison with solely nature-based interventions; LandCare: Standard costs | Standard as per the DEA NRM programme | Standard budgets although slightly higher than usual | Standard as per the DEA NRM programme | Conservancy: Standard as per the DEA NRM programme; Farm: as per farm practice |

| Partnerships | Low | Low | Some | Several | Some | Several | Several | Conservancy: several; Farm: some |

| Co-funding | Limited | Some |

CapeNature: none; Pollution Mgt: landowners |

SRM: limited; LandCare: landowners | Limited | Multiple from various sources | Some, including landowners | Conservancy: landowners |

| Training | Highly trained and specialised | Standard |

CapeNature: standard; Pollution Mgt: specialised |

SRM: highly trained and specialised; LandCare: standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard |

| Jobs | Permanent or semi-permanent | Short-term, aim to benefit many |

CapeNature: short-term, aim to benefit many; Pollution Mgt: permanent or semi-permanent |

SRM: Permanent; LandCare: some short-term but also longer-term contracts | Permanent or semi-permanent | Focus on longer-term contracts | Focus on longer-term contracts |

Conservancy: Short-term, aim to benefit many; Farm: Permanent |

| Potentially scalable | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Factors of potential for scaling (see bottom of table for explanation) |

(a)a Yes (b)b Yes (c)c Yes |

(a) Yes (b) Yes (c) Yes |

(a) Yes (CapeNature) (b) No (c) Yes (CapeNature) |

(a) Yes (b) No (c) No |

(a) Yes (b) Yes (potentially) (c) Yes |

(b) No (c) No |

(a) Yes (at micro scale on every well-run farm; can aggregate to macro-scale) (b) Yes (can aggregate nation-wide) |

|

| Current barriers to scaling | DEA NRM annual budget cycles with issues of “stop-start” funding flows and unpredictability of allocations and payment dates from year to year | DEA NRM annual budget cycles with issues of “stop-start” funding flows and unpredictability of allocations and payment dates from year to year |

Provincial programmes not found in this form in other provinces Pollution management programme is very small (human & financial) |

Provincial programmes not found in this form in other provinces SRM river stabilisation only suitable in specific circumstances and not favoured by many proponents of NBS |

BGCMA is one of only two CMAs that are formally established in SA under the National Water Act. Potentially all CMAs could anchor this typology across the country. The stakeholders preferred the similar but more inclusive and collaborative CAW typology. (#6) as having more potential for scaling | BGCMA is one of only two CMAs that are formally established in SA under the National Water Act. Potentially all CMAs could anchor this typology across the country. The stakeholders preferred this typology to the Water Sector typology (#5) as having more potential for scaling | There are limited numbers of environmental NGOs in this space and they are concentrated around larger centres nationwide. They are usually small (human & financial) | There are limited numbers of Conservancies and they are not well distributed spatially. They can play a role but scaling will depend largely on individual farmers/landowners |

The scalability of each typology, the factors of scalability, and some of the barriers to scalability are also indicated, as perceived by the stakeholders

aExisting financial management structures and practices are geared towards large budgets and there is scope to manage significantly larger budgets should large-scale funding from current or new sources become available

bGovernance and financial management structures exist across the country

cThe typology, i.t.o. its prevalent water-related EI interventions, can have a high impact across large spatial scales where restoration is greatly needed

dSince WfWet is sub-contracted by other projects on a needs basis it is not represented directly in the project inventory

eSRM: Driven by government obligations w.r.t the National Water Act and the Conservation of Agricultural Resources Act. A highly controlled approach based on engineered interventions. LandCare: Since this typology has transitioned into the Collaborative Agriculture & Water (CAW) typology it is not represented directly in the project inventory (last five years)

fImproved LandCare approach to clearing on agricultural land, now focused on a collaborative landscape approach; two mentoring organisations (LandCare, WWF-SA)

Potential for scaling

Four qualitative EI intervention typologies were identified as having potential for scaling out (Table 2): DEA NRM Specialised (S); Local Government (LG); Collaborative Agriculture and Water (CAW); Landowner/Conservancy (LC). These were deemed to offer opportunities for greater investment across catchment landscapes nationally, as financial management structures and governance arrangements exist everywhere and there is scope for expanded management of financial and human resources, leading to high spatial impact. In contrast, the other four typologies offer contextualised value in close collaboration with local communities and/or for sectoral interests, and at sub-national levels. Some of the current barriers to scaling of each typology are listed in Table 2 and are further addressed in the Discussion.

Quantitative EI intervention typologies

In Fig. 4, the results of the MCA are presented, where in Fig. 4a the unique codes in different colours represent the individual projects in the inventory and their original qualitative groupings into eight typologies (T1 to T8, by colour). This allows a visual separation of the eight typologies along the first two dimensions of the MCA. The first two dimensions explain in total 27.6% of the variance in the dataset.

Fig. 4.

a MCA plot showing the relationships between individual projects giving rise to various clusters (typologies) of EI interventions. Colours indicate the eight original qualitative EI intervention typologies as described in Table 2 (T1-8). Unique IDs are: (S) DEA NRM Specialised, (LG) Local Government, (EPSG) Provincial/State Government Environment Department, (APSG) Provincial/State Government Agriculture Department, (WS) Water sector, (CAW) Collaborative agriculture and water, (ENGO) Environmental non-government organisation and (LC) Landowner/Conservancy. b Significance of variables in explaining the clustering (for all clusters)

For the overall analysis of all data in the HCPC (all clusters), several variables contributed significantly to characterising the emerging clusters at P < 0.05 (Fig. 4b). The top five variables were Budget (category of annual budget size); Lead Organisation (responsible organisation); Partnership Complexity (complexity of partnership arrangements); Budget Landowner Contribution (relative contribution of a private landowner to the annual project budget); and the type of training/skills development provided (standard or specialised). These and other significant variables were representative of all the broad themes in the inventory (Table 1) so that the structure and characteristics of the typologies did not emphasise certain dimensions but rather showed an integration of biophysical and financial/organisational characteristics and socio-economic benefits. This gave us confidence that the typologies were not biased by different numbers of variables per theme. Based on the results of the HCPC, seven clusters representing EI intervention typologies were delineated (Fig. 5). The clusters (typologies) are described in Table 3 with reference to a selection of key variables.

Fig. 5.

Factor plot visualising the groupings from the dendrogram (Fig. S2) along the first two dimensions (dim 1 and 2) with the importance of the dimension given as %. Clusters are coloured according to the seven grouping from the dendrogram, however case studies are labelled according to the original unique ID’s: (S) DEA NRM Specialised, (LG) Local Government, (EPSG) Provincial/State Government Environment Department, (APSG) Provincial/State Government Agriculture Department, (WS) Water sector, (CAW) Collaborative agriculture and water, (ENGO) Environmental non-government organisation and (LC) Landowner/Conservancy

Table 3.

Descriptions of the seven quantitative water related EI intervention typologies in the Berg River and Breede River catchments, South Africa

| Variable | Typology | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Projects |

LG.1.2.3.4.7.8 EPSG.1.3.4 |

S.1.2 |

WS.1.2.3.4 LG.5.6 CAW.2 |

LC.1.2 ENGO.1 |

CAW.1.3 | EPSG.2.5.6 | APSG.1 |

| Catchment |

Berg Breede Riviersonderend |

Berg Riviersonderend |

Breede Riviersonderend |

Berg | Breede |

Berg Breede |

Riviersonderend |

| Lead organisation | CapeNature (provincial), Metropolitan, Local and District Municipalities | National Department of Environmental Affairs: Working on Fire | Breede Valley public and private water-related institutions and environmental NGO | Private sector and environmental NGOs | LandCare (through provincial Department of Agriculture) | Provincial Department of Environmental Affairs | Provincial Department of Agriculture |

| Land use | Conservation | Conservation | Agriculture and mixed agriculture & conservation | Agriculture and mixed agriculture & conservation | Mixed agriculture & conservation | Mixed agriculture & conservation | Mixed agriculture & conservation |

| Land owner | Public | Public | Both public and private | Private and both | Both | Both | Public |

| EI type |

Mountain catchment Riparian zone Wetland |

High altitude mountain catchment |

Mountain catchment Riparian zone Wetland |

Mountain catchment Riparian zone |

Mountain catchment Riparian zone |

Mountain catchment Riparian zone |

Riparian zone (threatened tributaries) |

| EI intervention |

Initial clearing of IAPs Follow-up clearing |

Initial clearing of IAPs Proactive fire management and fire risk reduction |

Initial clearing of IAPs Follow-up clearing Rehabilitation of wetlands and riparian areas that have been cleared |

Initial clearing of IAPs Follow-up clearing Proactive fire management and fire risk reduction Rehabilitation of wetlands and riparian areas that have been cleared |

Initial clearing of IAPs Follow-up clearing Rehabilitation of wetlands and riparian areas that have been cleared |

Initial clearing of IAPs Follow-up clearing Proactive fire management and fire risk reduction Rehabilitation of wetlands and riparian areas that have been cleared |

Built infrastructure for river stabilisation Initial clearing of IAPs Rehabilitation of wetlands and riparian areas that have been cleared |

| Partnership complexity | Low (Government/implementer) | Low (Government/implementer) | Low (Government/implementer) to high (Government, Water, Agriculture, Business) | Low (Private) or medium (Private/Government) | High (Government, Water, Agriculture, Business) | Medium (Government, Agriculture) | High (Government, Water, Agriculture) |

| Funding sources (main) |

National Treasury Provincial Treasury |

National Treasury |

National Treasury NGO |

National Treasury Landowner |

National Treasury Landowner |

Provincial Treasury | National Treasury |

| Number of funding sources (main and co-funding) | 1–2 | 1–2 | 1–10 | 1–5 | 6–10 | 1–10 | 1–2 |

| Funding channelled through | Local and Provincial Governments | National Government |

National Government and/or landowner |

National Government and/or landowner |

Catchment Management Agency | Provincial Government | National Government |

| Private landowner contribution | None | None | 0–20% | 0–100% | 1–20% | 1–20%, in-kind | In-kind |

| Budget | Standard | Specialized (more expensive) | Standard | Standard | Standard | Standard | Civil engineering (very expensive) |

| Job creation |

15–120 people per annum Mainly short term with some contract jobs |

50–120 people per annum Semi-permanent to permanent jobs |

< 15 to 120 people per annum Mixture of short term and contract jobs |

< 15 to 50 people per annum Contract, semi-permanent and permanent jobs |

15–120 people per annum Contract, semi-permanent and permanent jobs |

15–50 people per annum Contract jobs |

15–50 people per annum Semi-permanent to permanent jobs |

| Source of employees | Mainly from towns close by | From towns close by | From towns close by | From towns close by | From towns in an extended area | From towns in an extended area | From towns close by (labour) or further afield (engineer) |

| Training | Standard | Specialized (high altitude rope work) | Standard | Standard | Standard | Specialized (plant propagation and planting) | Specialized (civil engineering) |

| Benefits/goals | Manage and protect biodiversity in conservation areas, create many jobs while doing so, and secure water yields |

Manage and protect biodiversity, increase water yields security, and mitigate fire risk |

Secure water flows for water users in the Breede River Valley, and increase catchment resilience |

Secure water flows for irrigated agriculture, and realise local socioeconomic potential including ecotourism | Increase water supply security and mitigate risks for agriculture, and manage agricultural natural resources | Reduce water pollution | Stabilise river banks, reduce soil erosion and sedimentation, and mitigate flood risks as part of the mandate to manage agricultural natural resources |

| Comments | Uses the original DEA NRM programme (Working for Water)a that has been rolled out nationwide | Uses the original DEA NRM programme (Working on Fire) that has been rolled out nationwide (similarly for Working for Wetlands which is also specialized) | Locally developed landscape model using the active presence of the Breede-Gouritz Catchment Management Agency (BGCMA) in the context of multiple water user groups | Locally contextualised landscape model implemented by private landowners and NGOs | A collaborative agriculture and water model with multiple partners and funders which was developed by LandCare actors | A model that specifically addresses the strengthening of ecosystem services relating to water purification through natural riverine plant assemblages | Conventional model for built infrastructure aimed at risk reduction and sediment management |

Entries in Italic signify key significant variables that distinguish each typology

aSee Box S1

One qualitative typology (S) remained intact as typology #2. Three qualitative typologies (WS, LC, ENGO) were combined with other typologies or sub-groupings of other typologies in the quantitative typologies. In typology #3, the original Water Sector (WS) typology was augmented with the projects managed by the Breede Valley Local Municipality (LG) and WWF-SA (CAW). These projects are all situated in the Breede River catchment close to the main stem of the river, where this approach is linked to the active presence of the Breede-Gouritz Catchment Management Agency (BGCMA). In addition, the interventions are implemented across a multi-use patchwork landscape on both conserved and agricultural land where actors (major water users) are jointly invested in securing water yields. The remainder of the Local Government (LG) projects were grouped with the EPSG(i) projects managed by the Provincial/State conservation agency (CapeNature) in quantitative typology #1. The binding factors are the focus on conserved public lands, low partnership complexity and job creation for as many beneficiaries as possible according to the DEA NRM programme.

The landowner/conservancy (LC) and environmental NGO (ENGO) typologies merged (typology #4) after the quantitative analysis. The binding factors are their location in the upper Berg River catchment, and that they are initiated and managed by private actors, either landowners who fully fund the project or make considerable financial contributions, or local NGOs. They also both enjoy benefits of strengthened ecotourism. The Collaborative Agriculture and Water (CAW) typology emerged as quantitative typology #5 after losing the WWF-SA project (CAW.2) to quantitative typology #3. After the EPSG(i) (CapeNature) projects split off the original EPSG typology, the remaining EPSG(ii) projects (Pollution Management Directorate) became quantitative typology #6. This is a relatively specialised typology focusing on the propagation and re-planting of natural riverine plant assemblages for improved water quality. Lastly, the sub-group APSG(i) in the qualitative typology Provincial/State Government Agriculture emerged as a distinct typology (#7) after the quantitative analysis. This is also highly specialised, involving built infrastructure on river banks aimed at flood risk reduction and sediment management.

Discussion

We conducted a complementary qualitative and quantitative analysis of typologies of collaborative governance and financial arrangements in existing EI interventions in complex catchment landscapes. We first compare the qualitative and quantitative typology sets and reflect on the methodology, its limitations, and its replicability to other types of NBS and other catchment landscapes. We then discuss the key factors that play out in the emergence of different EI intervention typologies, and the lessons learned with respect to scalability in the South African context and beyond.

EI intervention typologies: A method for robust outcomes

The qualitative and quantitative sets of typologies agree in many respects. This addresses our research question ‘Do the quantitatively identified typologies agree with the qualitatively identified typologies, and, if not, what are the other factors of importance’. Both sets are characterised by varying degrees of complexity in partnership and financial arrangements; the size of the budget; the central role of the lead organisation; the role and financial contribution of private landowners, and the type of EI being restored. Both sets successfully integrate the environmental, social, economic and governance dimensions. Since all typologies included multiple water-related benefits such as the maintenance of healthy surface water flows, assurance of base flows in the dry season, and mitigation of drought, these factors did not play a role in distinguishing the typologies.

However, we found interesting shifts in the groupings after the quantitative analysis. New combinations added insights by highlighting the previously unexplored dimension of shared primary goals and motivators. In typology #3 (the reconstituted Water Sector typology), the common goal is to secure water yields for the main users in the catchment landscape. The Catchment Management Agency, Local Municipality and Water User Associations collectively strive toward the common objective of providing security of water supplies to their users/members. The actors in typology #5 (Collaborative Agriculture and Water) share the goal of water supply security, but have taken it further by incorporating a focus on agricultural natural resources management (through a LandCare programme: http://elsenburg.com/services-and-programmes/landcare-services) and accessing multiple sources of private funding, motivated by risk reduction benefits for commercial farming. In typology #1 (Local Government), local municipalities and CapeNature (institutionally distant, as per original qualitative typologies, but merged after the statistical analysis) share the primary objective of managing and protecting biodiversity in conservation areas under their jurisdiction, and creating many jobs, with the secondary objective of achieving security of water yields. Where EI interventions are initiated by private actors (typology #4) the shared motivation extends to new opportunities for socio-economic development through ecotourism.

Typologies are only useful if they capture complex realities. By employing a sense-making and typology verification process with a diverse group of landscape actors, we gained confidence that the refined typologies were a valid reflection of the lived reality and a robust scientific output. The multivariate statistical analysis added confidence by yielding results that further validated many aspects of the qualitative typologies but also altered the outcome in illuminating ways. This granularity would not have been achieved using a single approach. We therefore recommend that future work should combine these approaches. Qualitative analysis generates a rich and contextualised information base provided by multiple sources and allows for questions around scalability. The quantitative analysis overcame preconceptions and blind spots inherent in expert-led but nevertheless subjective analysis (Alvarez et al. 2014). In this study, the quantitative analysis followed on the qualitative analysis. Possibly the reverse would not yield the desired results since the statistical outcomes could introduce bias during the qualitative process.

The stepwise sequential design and the detailed description of each step makes it possible to apply the methodology to other systems or to other types of NBS. However, certain limitations should be considered. We only captured the more top-down formal initiatives driven by bigger budgets, thus missing the actors with small budgets and low visibility, or efforts relying on volunteers, e.g. environmental, sports and recreation clubs using the mountains and rivers. These initiatives are not structured for larger financial flows or the generation of social benefits (except the health and enjoyment of the members). Another limitation is that less tangible factors such as the critical role of champions (Rouillard and Spray 2017), trust (Ostrom and Ahn 2003) between beneficiaries, implementers and investors, and the role of catchment-wide coordinating fora (Cockburn et al. 2020), are not well captured. These could be incorporated as an additional step.

A strength of the methodology is that it provides clarity on two scales. At the project scale we determined the level of complexity of partnerships, impacts in terms of job security, contribution and flow of financial resources, and the type of actors involved. At the landscape scale we showed how the high dependence on limited public funding has encouraged various actors to self-organise, leading to innovative advances in collaborative partnership development between public and private sector organisations.

What the typologies tell us about governance and scalability of EI interventions across catchment landscapes

Some “meta-factors” that play a critical role in the structure and function of the EI typologies include the source and size of funding, actor constellations and partnership complexity, and benefits and beneficiaries. Here, we discuss the research questions ‘What EI intervention types can be found in catchment landscapes as informed by the EI intervention inventory and expert knowledge?’ and ‘Which typologies could be scaled to large areas and many different contexts, considering their governance and financial management structures and modus operandi?’ For methodological consistency and clarity we refer here (second question) only to the qualitatively derived typologies.

The size of the budget, the financial contribution of private landowners, and the number of funding sources were key factors in characterising the different typologies. This underlines the importance of constrained funding in a country with significant developmental and service delivery needs but limited public resources (Shackleton et al. 2017). Public financing is dominant (DEA NRM programme), since the interventions deal with public or common goods (SANBI 2014). Most typologies depend on this programme and compete for the available funding. Comparatively little private sector funding is available, limited to World Wide Fund for Nature—South Africa (WWF-SA), landowners, and a small group of corporates, retailers and local businesses. The DEA NRM programme has been consistently granted substantial budgets, with annual spending in 2019 amounting to around ZAR 2 billion (USD 122 million) (van Wilgen et al. 2020). Nevertheless, funds are insufficient to tackle the full extent of EI intervention needs (van Wilgen and Wannenburgh 2016). Since prerequisites for scaling exist in typologies S (DEA NRM Specialised) and LG (Local Government) (Table 2), they are well placed to absorb greater investments for greater impact in catchment areas on state-owned land.

The constrained funding environment has stimulated the development of increasingly complex and fluid funding arrangements, including many public–private partnerships. This has provided greater resourcing and more financial stability but comes with high transaction costs and the delicate management of possibly competing objectives. New funding sources can drive the goals in new directions according to the motivations of the funders. Equally, specific beneficiary needs after funding might also drive the development of altered approaches. A valuable future research question is how increased private investments will shape these typologies to accommodate effective governance and implementation processes at scale while achieving multiple objectives. Typology CAW (Collaborative Agriculture and Water) offers a novel approach to scaled public–private investment in landscapes with significant irrigated agriculture, but demands considerable actor engagement. It developed from the need to operate collaboratively and overcome the challenges experienced with government-led interventions. Complex institutional arrangements with their high transaction costs (Schoon and Cox 2018) are, however, not easily transferable to other projects and contexts, and this may limit the scaling potential.

Despite the dominance of public “top-down” governance approaches, some typologies incorporate “bottom up” approaches. These are led by individual landowners, conservancies, Water User Associations, and NGOs partnering with Community-based Organisations, and are often strongly linked to champions and local support networks. Since benefits of sustained water availability and risk reduction (to mitigate against floods and fires) are increasingly acknowledged by private landowners, they now routinely provide co-funding in the form of cash or in-kind for work performed on their lands. Moreover, the LC typology, where landowners drive and eventually fully fund and manage the process, was seen by stakeholders to be ideal for scaling up EI interventions across privately managed landscapes.

The Lead Organisation is an important typology variable, suggesting that individual institutions have each developed preferred ways of implementing such projects, to ensure desired outcomes. Possible reasons are specific legal mandates, hydro-ecological and social benefit objectives (expectations of “return on investment”), monitoring and financial control mechanisms, resource constraints, and the search for innovative ways to overcome bureaucratic barriers. Lead Organisations, often public institutions, are developing working relationships and collaborations with specific actors from diverse public and private backgrounds including managers within specific catchments. This fills capacity gaps in government, improves coordination and impact in a given area, and covers differing mandates and jurisdictions. Lambin et al. (2020, p. 89) note that “upscaling almost always involves collaboration among public, private, and civil society actors”. This can lead to increasingly complex partnership numbers and arrangements.

Typologies EPSG (Pollution Management) and APSG (River Stabilisation) are province-specific projects funded via Provincial/State budgets and are relatively specialised and locally contextualised, and not directly suited to nationwide scaling. APSG (River Stabilisation) is an outlier since its budgets are linked to disaster risk management in the agricultural sector and are orders of magnitude greater than those of other typologies owing to engineered built infrastructure such as groynes. Because governance and financial structures supporting the engineered approach are firmly established, such projects have access to a diversity of finance options. A similar choice of finance options, especially from the private sector, should be developed for pure EI and complementary EI—built infrastructure projects (The Nature Conservancy 2019).

Scalable typologies must also demonstrate the generation of intended benefits while ensuring that funder and implementer motivations are equally satisfied. All EI typologies have a complex mix of intended benefits covering ecological, social and economic dimensions. The social “return on investment” is key in the South African “EI landscape” but has proven to be somewhat elusive (McConnachie et al. 2013). Direct beneficiaries include landowners (on site), contractor teams and their workers from nearby communities, while downstream communities including urban areas receive indirect benefits in the form of sufficient and clean water (The Nature Conservancy 2019). Projects are structured to yield the greatest possible benefit for poor and marginalised populations. The typologies are partially distinguished by the difficult trade-off required between job creation and livelihood security. Typology LG (Local Government) aims for employment of large numbers of previously unemployed beneficiaries, but for periods of only a few months. In contrast, typology S (DEA NRM Specialised) provides extensive specialised training to selected applicants followed by permanent employment. Both have potential for out-scaling but with differing primary and secondary benefits. Other typologies have adjusted their practices to increase job security for less skilled workers. A criticism of the South African effort is that funders and governing actors have prioritised the job creation benefits at the expense of maximising the long-term hydro-ecological benefits and preventing future loss of water yield (McConnachie et al. 2013; van Wilgen and Wannenburgh 2016). The typologies remind us that partnership and financial arrangements should be responsive to the intended mix of spatial and temporal benefits. A bottom up approach to planning includes an assessment of what constitutes “return on investment” for beneficiaries and building of local trust-based relationships between implementers and beneficiaries. This approach should lead to the optimum choice of EI intervention type or evolution of more effective types in the local context. This remains essential even with scaled up funding and new funding sources.

Policy-led efforts and associated funding by national government (DEA NRM programmes) will continue to shape governance structures and arrangements. However, more inclusive and innovative public–private partnerships have evolved looking at EI from a more systematic landscape perspective. While these have overcome some of the rigid top-down governance barriers, their complexity of arrangement may add to the coordination challenge. Governance efforts driven by local actors (private landowners, NGOs) are gaining significance and this highlights that differing project goals (relating to water, risk reduction, conservation, legislation) can be coalesced to drive collective action. Our findings show that with a level of political will, departments representing different sectors and spheres of government can all pursue NBS objectives.

While the typologies are uniquely South African in the detail, they show similarities to those identified in other countries, e.g. government-led “top-down”, hybrid public–private, “bottom-up” private or citizen-led initiatives (Diaz-Kope and Miller-Stevens 2015), the key role of collaborative governance (Schoon and Cox 2018) and shared project motivations (Zingraff-Hamed et al. 2017). This suggests that our findings are meaningful in other contexts and some may be transferable. The discourse around NBS is still mostly focused on the Global North. To fulfil its purpose as a global concept/approach, additional elements may require deeper consideration. Our work reflects some of the barriers and opportunities encountered in the developing world, such as large gaps in resourcing and capacity and the need to provide multiple environmental and socio-economic co-benefits. Finally, we have highlighted several dimensions of scaling EI interventions that can contribute to the further discourse towards a conceptual framework of NBS scaling. Further research is required to understand the complex interplay of conditions that provide opportunities for scaling, but also barriers and trade-offs, in different typologies, and identifying the ‘optimal’ level of scale for each. In future, a range of EI intervention typologies with differing biophysical and socioeconomic outcomes could provide choices for investors with specific goals, but aggregate to provide landscape wide benefits to ecosystems and people and livelihoods.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Electronic supplementary material 1 (PDF 1317 kb)

Electronic supplementary material 2 (XLSX 26 kb)

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA) for funding the research undertaken under the SEBEI (Socio-Economic Benefits of Investing in Ecological Infrastructure) Project, Grant No.: 17-M07-KU. We also thank other members of the SEBEI project team for their contributions, and all the stakeholders that participated in the research process.

Biographies

Stephanie J. E. Midgley

is a Research Associate of the African Climate & Development Initiative (ACDI), University of Cape Town, South Africa. Her research interests include sustainable agriculture at the interface with conservation and natural resources management, climate change impacts and adaptation in agro-ecological systems, and the food-energy-water-environment nexus. She also conducts applied research on deciduous fruit production in a stressful climate.

Address: African Climate & Development Initiative (ACDI), University of Cape Town, Private Bag X3, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa. e-mail: stephanie.midgley@gmail.com

Karen J. Esler

is a Professor at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. Her interdisciplinary research interests include understanding how drivers of change (e.g. over-exploitation, habitat fragmentation and alien invasion) influence population and community structure and processes in Mediterranean-type ecosystems, arid ecosystems and riparian vegetation. The applied aspect of this work has been to develop and translate best-practice advice for management, restoration and conservation.

Address: Department of Conservation Ecology & Entomology, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Matieland, 7602, South Africa. e-mail: kje@sun.ac.za

Petra B. Holden

is a Postdoctoral Research fellow at the African Climate & Development Initiative (ACDI), University of Cape Town, South Africa. Her research interests include restoration ecology, conservation biology, nature-based solutions, climate change, hydrology, and remote sensing.

Address: University of Cape Town, African Climate & Development Initiative (ACDI), Private Bag X3, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa. e-mail: petra.holden@uct.ac.za

Alanna J. Rebelo

is a Postdoctoral Researcher at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. Her research interests include wetland ecology, ecosystem service science, applied remote sensing, and ecohydrology.

Address: Department of Conservation Ecology & Entomology, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Matieland, 7602, South Africa. e-mail: ARebelo@sun.ac.za

Sabine I. Stuart-Hill

is a Lecturer at the University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany. She is also a research fellow of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and a senior research associate at the Centre for Water Resources Research. Her research interests include integrated water resources management, sustainable transformations of complex systems, water governance, adaptive management, and climate change adaptations.

Address: University of Koblenz-Landau, PO Box 201 602, 56,016 Koblenz, Germany. e-mail: stuarthill@uni-koblenz.de and Stuart-Hills@ukzn.ac.za

James D. S. Cullis

is a Technical Director in the water resources group at Zutari, and an Honorary Research Associate of the African Climate & Development Initiative (ACDI), University of Cape Town (UCT), South Africa. His research interests include hydrology, hydro-economics, water resources management, water infrastructure planning and design, investing in ecological infrastructure, environmental flow requirements, and climate change impacts and adaptation.

Address: Zutari (Pty) Ltd., 1 Century City Drive, Waterford Precinct, Century City, 7441, South Africa. e-mail: james.cullis@zutari.com

Nadine Methner

is a Senior Researcher at the African Climate & Development Initiative (ACDI), University of Cape Town, South Africa. Her research interests include complex governance systems, integrated natural resources management, adaptive capacity of local and regional organizations through collective learning and collaboration, and inter- and transdisciplinary methods for co-production of knowledge on climate change adaptation and strengthening social equity.

Address: University of Cape Town, African Climate & Development Initiative (ACDI), Private Bag X3, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa. e-mail: nmethner@gmail.com

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alvarez S, Paas W, Descheemaeker K, Tittonell P, Groot J. Typology construction, a way of dealing with farm diversity. General guidelines for Humidtropics. Wageningen: Humidtropics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Angelstam P, Barnes G, Elbakidze M, Marais C, Marsh A, Polonsky S, Richardson DM, Rivers N, et al. Collaborative learning to unlock investments for functional ecological infrastructure: Bridging barriers in social-ecological systems in South Africa. Ecosystem Services. 2017;27:291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J, Blignaut JN, Aronson TB. Conceptual frameworks and references for landscape-scale restoration: Reflecting back and looking forward. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 2017;102:188–200. doi: 10.3417/2017003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boretti A, Rosa L. Reassessing the projections of the World Water Development Report. npj Clean Water. 2019;2:15. doi: 10.1038/s41545-019-0039-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cash DW, Adger WN, Berkes F, Garden P, Lebel L, Olsson P, Pritchard L, Young O. Scale and cross-scale dynamics: Governance and information in a multilevel world. Ecology & Society. 2006;11:8. doi: 10.5751/ES-01759-110208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn J, Cundill G, Shackleton S, Cele A, Cornelius SF, Koopman V, le Roux JP, McLeod N, et al. Relational hubs for collaborative landscape stewardship. Society & Natural Resources. 2020;33:681–693. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2019.1658141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Shacham E, Walters G, Janzen C, Maginnis S. Nature-Based Solutions to address societal challenges. Gland: International Union for Conservation of Nature; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Shacham E, Andrade A, Dalton J, Dudley N, Jones M, Kumar C, Maginnis S, Maynard S, Nelson CR, et al. Core principles for successfully implementing and upscaling nature-based solutions. Environmental Science & Policy. 2019;98:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2019.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coppus R, Romijn JE, Méndez-Toribio M, Murcia C, Thomas E, Guariguata MR, Herold M, Verchot L. What is out there? A typology of land restoration projects in Latin America and the Caribbean. Environmental Research Communications. 2019;1:041004. doi: 10.1088/2515-7620/ab2102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell JW, Plano Clark VL, Gutmann M, Hanson W. Advanced mixed methods research designs. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- Cullis JDS, Görgens AHM, Marais C. A strategic study of the impact of invasive alien plants in the high rainfall catchments and riparian zones of South Africa on total surface water yield. Water SA. 2007;33:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cullis JDS, Horn A, Rossouw N, Fisher-Jeffes L, Kunneke MM, Hoffman W. Urbanisation, climate change and its impact on water quality and economic risks in a water scarce and rapidly urbanising catchment. Case study of the Berg River catchment. H2Open Journal. 2019;2:146–167. doi: 10.2166/h2oj.2019.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming TL, Shackleton RT, Förster J, Dini J, Khan A, Gumula M, Kubiszewski I. Achieving the national development agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through investment in ecological infrastructure: A case study of South Africa. Ecosystem Services. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Kope L, Miller-Stevens K. Rethinking a typology of watershed partnerships: A governance perspective. Public Works Management & Policy. 2015;20:29–48. doi: 10.1177/1087724X14524733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DWA. 2010. Assessment of the ultimate potential and future marginal cost of water resources in South Africa. DWA Report No. P RSA 000/00/125610. Department of Water Affairs, Pretoria, South Africa.

- Ershad Sarabi S, Han Q, Romme AGL, de Vries B, Wendling L. Key enablers of and barriers to the uptake and implementation of nature-based solutions in urban settings: A review. Resources. 2019;2019:121. doi: 10.3390/resources8030121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fastenrath S, Bush J, Coenen L. Scaling-up nature-based solutions. Lessons from the Living Melbourne strategy. Geoforum. 2020;116:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CC, Ostrom E, Ahn TK. The concept of scale and the human dimensions of global change: A survey. Ecological Economics. 2000;32:217–239. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00092-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano R, Pluchinotta I, Pagano A, Scrieciu A, Nanu F. Enhancing nature-based solutions acceptance through stakeholders’ engagement in co-benefits identification and trade-offs analysis. Science of the Total Environment. 2020;713:136552. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, T., J.N. Blignaut, and C. Marais. 2012. Natural resource management – an employment catalyst: The case of South Africa. Working Paper Series No. 33. Development Bank of Southern Africa, Johannesburg.

- IUCN. 2017. Invasive alien species and climate change. Issues Brief. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/invasive-alien-species-and-climate-change.

- Lam DPM, Martín-López B, Wiek A, Bennett EM, Frantzeskaki N, Horcea-Milcu AI, Lang DJ. Scaling the impact of sustainability initiatives: A typology of amplification processes. Urban Transformations. 2020;2:3. doi: 10.1186/s42854-020-00007-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambin EF, Kim H, Leape J, Lee K. Scaling up solutions for a sustainability transition. One Earth. 2020;3:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2020.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McConnachie MM, Cowling RM, Shackleton CM, Knight AT. The challenges of alleviating poverty through ecological restoration: Insights from South Africa's “Working for Water” Program. Restoration Ecology. 2013;21:544–550. doi: 10.1111/rec.12038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore EA, Koontz TM. A typology of collaborative watershed groups: Citizen-based, agency-based, and mixed partnerships. Society & Natural Resources. 2003;16:451–460. doi: 10.1080/08941920309182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M-L, Riddell D, Vocisano D. Scaling out, scaling up, scaling deep. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship. 2015;58:67–84. doi: 10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2015.ju.00009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murcia CMR, Guariguata A, Andrade GI, Andrade J, Aronson EM, Escobar A, Etter FH, Moreno WR, et al. Challenges and prospects for scaling-up ecological restoration to meet international commitments: Colombia as a case study. Conservation Letters. 2016;9:213–220. doi: 10.1111/conl.12199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom E, Ahn TK. Foundations of social capital. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Perring MP, Erickson TE, Brancalion PHS. Rocketing restoration: Enabling the upscaling of ecological restoration in the Anthropocene. Restoration Ecology. 2018;26:1017–1023. doi: 10.1111/rec.12871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prewitt V. Working in the café: Lessons in group dialogue. The Learning Organization. 2011;18:189–202. doi: 10.1108/09696471111123252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ros-Tonen MAF, Reed J, Sunderland T. From synergy to complexity: The trend toward integrated value chain and landscape governance. Environmental Management. 2018;62:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00267-018-1055-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouillard JJ, Spray CJ. Working across scales in integrated catchment management: Lessons learned for adaptive water governance from regional experiences. Regional Environmental Change. 2017;17:1869–1880. doi: 10.1007/s10113-016-0988-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SANBI . A framework for investing in ecological infrastructure in South Africa. Pretoria: South African National Biodiversity Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schoon M, Cox ME. Collaboration, adaptation, and scaling: Perspectives on environmental governance for sustainability. Sustainability. 2018;2018:679. doi: 10.3390/su10030679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton RT, Angelstam P, van der Waal B, Elbakidze M. Progress made in managing and valuing ecosystem services: A horizon scan of gaps in research, management and governance. Ecosystem Services. 2017;27:232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.11.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Termeer CJAM, Dewulf A, van Lieshout M. Disentangling scale approaches in governance research: Comparing monocentric, multilevel, and adaptive governance. Ecology and Society. 2010;15:29. doi: 10.5751/ES-03798-150429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]