Abstract

Steroidal gylcosides are the predominant metabolites of starfish and are responsible for various biological activities. Some of these activities are recognized as a part of self-defense mechanism of starfish. Cholesterol-binding ability was evaluated with seven starfish crude extracts, where significantly (p < 0.05) highest ability (34%) was observed in Asterias amurensis and the lowest (16%) was attributed in Distolasterias nippon. To characterize the active compound exists in crude saponin from A. amurensis, the extract was subjected to thin layer chromatography following silica gel column chromatography. As the results, seven fractions (fr. A-G) were separated and frs. D and F demonstrated the highest cholesterol-binding ability (32% and 33%, respectively), equivalent to that of the A. amurensis extract. The isolated component (fr. F) was further separated (fr. F1–F3) for structural analysis. Based on cholesterol-binding ability result (29%), fr. F2 was analysed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time-of-flight mass spectroscopy (MALDI-TOF MS) and then nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR). The compound was identified as thornasteroside A, one of the major bioactive compounds already found in A. amurensis. The discovery of a saponin with cholesterol-binding ability has important implications not only for the utilization of starfish but also for food and pharmaceutical research.

Keywords: Starfish saponin, Cholesterol-binding ability, Thornasteroside A, MALDI-TOF MS. NMR

Introduction

Saponins are natural glycosides, which are widely distributed in the plant kingdom and some marine animals like sea cucumbers (Holothuriidae) and starfish (Asteroidea) (Caulier et al. 2011; Andersson et al. 1989). They consist of a sugar moiety (i.e., glucose, galactose, pentose, and xylose) combined with a hydrophobic aglycone (i.e., sapogenin) (Ishizaki et al. 1997) and play defensive roles against infectious agents (Kubanek et al. 2002). Many plant extracts contain saponin, especially obtained from Saponaria officinalis (soponin), and Quillaja saponaria (quillaja), traditionally have been used as soap (Augustin et al. 2011; Vincken et al. 2007). It was also reported that saponins from ginseng root (Panax ginseng) have been used as one of the traditional Chinese medicines for a long time (Park et al. 2009). In mammalian cells, saponins affect various pathways at the molecular level, providing many interesting pharmacological activities including anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulating (Song and Hu 2009), and anti-diabetic activities (El Barky et al. 2017). It was also reported that saponin acts on the central nervous (Matsuda et al. 1999) and endocrine systems. On the other hand, they are widely used in food and other industrial applications, mainly as surfactants and foaming agents (San and Briones 1999). Saponins also have the potential to be used for further industrial applications, for instance, as food preservatives, flavour modifiers, and agents for removal of cholesterol from dairy products (San and Briones 1999). More recently, saponins derived from plants such as soybean, quillaja, tea seed, and balloon flower were demonstrated to have hypocholesterolaemic effects in serum (Zhao et al. 2008). In addition, α-tomatine and digitonin, are the major saponin in tomato and the flowering plant of foxglove respectively also have been proposed to the effect of cholesterol-lowering property (Cleamond et al. 1967; Courchaine et al. 1959). The growing evidence of the health benefits of saponins, such as their cholesterol-lowering properties, has recently renewed interest in edible and inedible sources of saponins.

Fundamental studies have shown the ability of different types of saponins to form complex with cholesterol. Windaus (1909) firstly reported the complex interactions between cholesterol and saponins, which spurred interest in possible industrial uses of saponins. Several studies show that saponins effectively remove cholesterol from dairy products. For instance, saponin from the soapbark tree, Q. saponaria has cholesterol binding affinity which can remove cholesterol from butter oil (Sundfeld et al. 1993). Digitonin has been successfully used in the selective separation of cholesterol from butterfat for the last few decades (Schwartz et al. 1967). On the other hand, Kabara et al. (1961) reported that tomatine has a greater specificity than digitonin for preparation and estimation of cholesterol and its ability to complex with, and remove cholesterol. Based on their reports, the mechanism of linking saponins with cholesterol is important in understanding such as the characteristics of membrane displacement and serum cholesterol function also interaction of cholesterol and saponins, make it possible to predict the function of cholesterol in food products and pharmaceutical matrixes.

Saponins have various useful effects as mentioned above, and searches for saponins from various organisms are also actively conducted. In the present study, we focused on the saponins from starfish. Starfish are common by-catches in the worldwide fishing industry. Although starfish are sometimes consumed in a few countries, there are no effective methods to utilize this resource on an industrial scale. On the other hand, it is well-known that starfish are marine invertebrates that are extremely rich sources of biologically active compounds, including saponins. Saponins, specifically asterosaponins, are the predominant metabolites of starfish (Echinodermata, Asteroidea) (D’Auria et al. 1993). Numerous studies have been conducted on these compounds that are characterized by a large chemical diversity and a wide variety of pharmacological activities (Kubanek et al. 2002). Starfish saponins have also been found to have some interesting biological and pharmacological activities, including anti-cancer properties (Gurfinkel and Rao 2003) as well as cytotoxic, hemolytic, and anti-fungal activities (Thao et al. 2014). However, the cholesterol-binding abilities of saponins derived from starfish have not been evaluated. Therefore, in the current study, the cholesterol-binding abilities of saponins from seven different species of Japanese starfish were evaluated, and the responsible bioactive compounds were identified.

Materials and methods

Biological material

Asterias amurensis, Distolasterias nippon, and Solaster paxillatus were collected from the coast of Kushiro, Hokkaido, Japan, in the summer of (June) 2011. Moreover, Acanthaster planci and Ophiura sarsii were gathered from the coasts of the Okinawa and Tottori Prefectures, Japan, in the autumn of (September) 2009, respectively. Finally, Astropecten scoparius and Patiria pectinifera were obtained from the coast of Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan, in the winter of (February) 2014. After the species identification of starfish was carried out on the basis of their phenotypic descriptions, i.e., the external structural appearances and morphological characteristics, all the starfish specimen were kept at − 30 °C until use.

Extraction and fractionation of starfish saponin

Crude saponin was prepared according to the methanol-extraction method described by Yasumoto et al. (1966). Briefly, one kilogram of starfish was cut into small pieces and then minced using a food grinder (Kitchen-Aid, St. Joseph, MI, USA). The extraction was performed using 3 L of methanol and repeated twice with 2 L of methanol, then filtered through Grade 2 Whatman filter paper (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The filtrate (250 mL) was concentrated by using a rotary evaporator (1 L Rotary Evaporator N-1001 Series, Eyela, Tokyo, Japan) under reduced pressure at 45 °C. The concentrate was subsequently stirred with an equal volume of water (250 mL) and defatted with 250 mL benzene. Once the extract was benzene-free, the pH of the extract was adjusted to 3 with 1 N hydrochloric acid and neutralized using 1 N sodium hydroxide. The extract was dialyzed through an ultra-filtration membrane (MWCO 1000, Millipore-Amicon, Billerica, MA, USA) and partitioned with n-butanol three times. After the 150 mL n-butanol extract was concentrated, 450 mL of diethyl ether and 75 mL of water were added. Finally, the aqueous layer was freeze-dried to provide glassy materials.

A portion of the extracts were subjected to silica gel (open) column chromatography (200–300 µm silica gel, 2.6 × 100 cm column, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) eluted with CHCl3: CH3OH:H2O (65:35:10, lower phase), and each fraction (10 mL) was collected with an Advantec® SF-2120 fraction collector (Advantec Toyo Kaisha Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The fraction was then concentrated to dryness in a rotary evaporator (N-1001 Series, Eyela World, Tokyo, Japan) at 45 °C and lyophilized to provide seven fractions: fr. A–G. Fraction F, which had the highest cholesterol-binding ability among fr. A–G, was further separated by using a normal-phase silica gel column (1.5 × 100 cm) and elution with a stepwise CHCl3:CH3OH:H2O gradient (90:10:1, 80:20:5, 70:30:10, and 65:35:10) to provide three sub-fractions: fr. F1–F3.

Evaluation of the cholesterol-binding abilities of saponin

The cholesterol-binding abilities were determined using the FeCl3-H2SO4 method described by Courchaine et al. (1959). Briefly, 2.5 g of FeCl3 was dissolved in H3PO4 and diluted to 100 mL with H3PO4 for the iron stock solution. Then, 8 mL of the iron stock solution was diluted to 100 mL with H2SO4 for the colour reagent. Next, a cholesterol stock solution (0.33 mg/mL) was prepared, diluted with 100% acetic acid prior to use. A standard curve was obtained by regression analysis using cholesterol standards (i.e., 0.03, 0.06, 0.10, 0.13, and 0.16 mg/mL Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan) for cholesterol quantification. 2 mL colour solution was added to the standard solution, which was kept at room temperature for 30 min; then, a 0.30 mg/mL cholesterol standard was prepared with a 50:50 acetone and 95% ethanol mixture. Starfish extracts (10 mg/mL) were subsequently diluted with distilled water and mixed with a 1 mL cholesterol standard. Next, the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, and the precipitated cholesterol-saponin was collected by centrifuging at × 350g for 5 min. Then the supernatant was discarded and 4 mL of acetone was added to precipitate solids in a suspended form. Finally, the tubes were inverted for 15 min, and then 3 mL of acetic acid and a 4 mL colour solution were added. The mixture allowed to stand for 3 h at room temperature and absorbance was measured at 550 nm with a spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). A specimen containing only the colour reagents was used to set the spectrophotometer at zero absorbance. Quillaja bark (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd.) and tea seed saponins (Sigma-Aldrich) were used as positive controls; they produced colour due to reaction of aglycon of the saponins and reagent. The values obtained from the calibration curve represent both free and total cholesterol in milligrams. The amount of saponin bound cholesterol was obtained by subtracting the amount of free cholesterol from that of total cholesterol. Therefore, the percentage of saponin bound cholesterol was calculated using the following equation:

Identification of the bioactive compound

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on glass plates pre-coated with silica gel 60G F254 (10 × 20 cm, Merck Millipore) in order to confirm the composition of the crude saponin and fractionated saponin. The plates were developed with CHCl3:CH3OH:H2O (65:35:10, lower phase) and detected by spraying the plates with 50% sulfuric acid and 1% cinnamaldehyde followed by heating.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time-of-flight mass spectroscopy (MALDI-TOF MS) mass spectra were obtained using 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) as the matrix for the analysis of intact and derivatized saponins (1 μL of each sample dissolved in 100 µg/mL methanol), respectively, on a 4800 Plus MALDI®TOF/TOF™ Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA, USA). Acquisition was in the positive reflector mode in the m/z 800 and m/z 2500 range. The instrument was calibrated using the AB Sciex Mass Standards Kit for Calibration of AB SCIEX TOF/TOF Instruments. A reflector interpretation method was created to run the MS/MS 1 kV positive acquisition method in a batch mode on all spots. MS/MS was performed at a fixed-laser intensity of 4200 on the 50 strongest precursor peaks identified during reflector mode acquisition.

The nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis was performed on an AV600 spectrometer (Buker, Antioch, CA, USA) with one-dimensional (1D) and two-dimensional (2D) NMR. ID NMR (1H and 13C at 600 and 150 MHz, respectively) with distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer (DEPT) and 2D NMR (correlation spectroscopy [COSY], heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence [HMQC], and heteronuclear multiple bond coherence [HMBC] spectroscopy) was recorded. The analyses were performed using pyridine-d5 (C5D5N) as the solvent and determined chemical shifts using the δ scale, with pyridine d5 as the internal standard. NMR data processing was carried out with Top Spin version 3.2.

Statistical analysis

The analytical measurements were done in triplicates, and the results were presented as the average of three analyses ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was done using the SPSS statistical package (IBM Corp., IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 16.0, Armork, NY, USA) with one way ANOVA. A p value of < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant based on Duncan’s tests.

Results and discussion

Cholesterol-binding abilities of starfish saponin

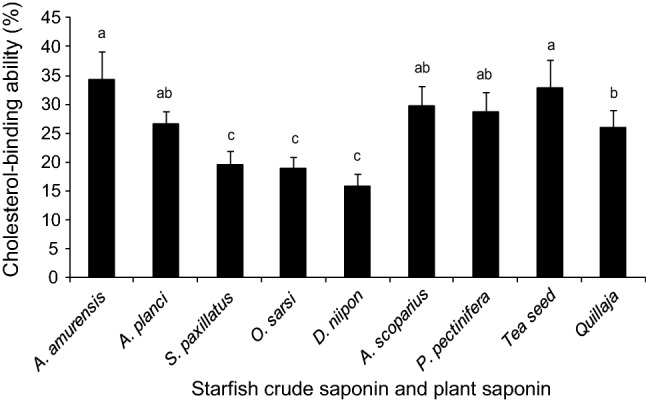

The cholesterol-binding ability of crude extracts from seven Japanese starfish such as A. amurensis, A. planci, D. nippon, S. paxillatus, O. sarsii, A. scoparius, and P. pectinifera were screened and compared in this study (Fig. 1). The significant (p < 0.05) cholesterol-binding ability was observed in the crude extract obtained from, A. amurensis (34%) and Tea seed saponin followed by those from A. scoparius, P. pectinifera, and A. planci (30, 29, and 27%, respectively). No significant (p < 0.05) differences were recorded among S. paxillatus (20%), O. sarsii (19%), and D. nippon (16%). The corresponding value recorded for D. nippon 16%, was approximately half than that of A. amurensis. It was revealed that the cholesterol-binding ability of the A. amurensis saponin was equivalent to that of plant saponin extracted from tea seed (Fig. 1). The complex formation between cholesterol and plant saponin has been investigated in the past few decades. As cholesterol is an amphipathic molecule, it can be supposed that the hydrophobic interaction occurs between the rigid rings of saponin and cholesterol. The hydrophilic interaction leading to the formation of the hydrogen bond network between the sugar moieties and cholesterol hydroxyl group are responsible for the monolayer disruption (Kubanek et al. 2002). The most widely known plant saponin, α-tomatine and digitonin also interact with cholesterol to form tightly bound non-covalent complexes in model membranes (Cleamond et al. 1967; Courchaine et al. 1959). However, the mechanism remains unclear regarding what happens to the cholesterol in the membrane after binding or disruption by the saponin.

Fig. 1.

Cholesterol-binding abilities of crude saponin from seven starfish species. Letters on top of each column indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05; one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s test)

Since plant saponin binds with cholesterol as mentioned above, it can be expected that saponin decreases the level of cholesterol in the body. In fact, it has been reported that tea seed saponin reduced serum cholesterol in rats by 35% (Matsui et al. 2006). In addition, several studies have shown that administration of ginseng saponins may decrease serum cholesterol (Ayaz and Alnahdi 2018). Eskandar et al. (2015) also have been reported that some saponins may lead to prevention of hypercholesterolemia, the phenomenon which is the result of complex formation with cholesterol.

Therefore, saponins are considered effective for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Hypercholesterolemia is a major cause of cardiovascular disease such as atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease. Many patients prefer nondrug therapies for a number of reasons including adverse effects of anti-hyperlipidemic agents and allergic reactions to drugs. Consequently, it is necessary to develop safe and effective cholesterol-lowering agents from natural sources (EL-Farok et al. 2013). The results of this study demonstrated that saponins from Japanese starfish can bind with cholesterol with the same affinity as plant saponins, suggesting that Japanese starfish saponins can be used as cholesterol-lowering agents.

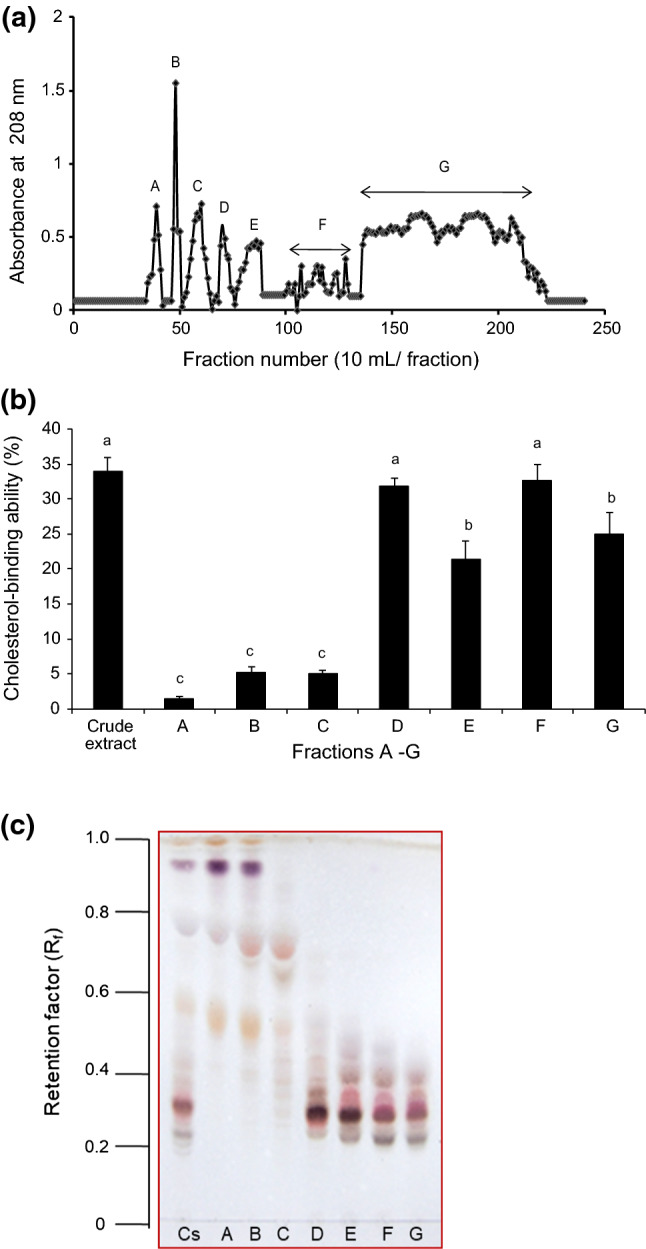

Fractionation of starfish saponin

As crude saponin extract obtained from A. amurensis possessed higher cholesterol-binding ability than the other starfish extracts, it was selected for further analysis. The A. amurensis extract was subjected to silica gel column chromatography and separated into seven fractions (Fig. 2a). Of the seven fractions (frs. A–G), frs. D and F demonstrated the highest cholesterol-binding ability (32% and 33%, respectively), equivalent to that of crude extract; meanwhile, frs. A, B, and C did not show remarkable cholesterol-binding abilities (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Silica gel column chromatogram of crude saponin from A. amurensis and the cholesterol-binding abilities of each fraction. Silica gel 60 column (0.040–0.063 mm) chromatographic conditions: column 2.6 × 100 cm; eluent: CHCl3:CH3OH:H2O (65:35:10, lower phase); flow rate: 5 mL/min; and 10 mL/fraction. a Silica gel chromatogram of extract from A. amurensis, b Cholesterol-binding abilities of the resultant fractions (designated A–G) and c the TLC results of the resultant fractions

TLC analysis of the seven fractions revealed two major differences in the number of discrete spots after the detection of saponin with a 50% sulfuric acid staining solution (Fig. 2c). Fractions A, B, and C consisted of components with relatively high Rf values ranging from approximately 0.5–0.9, while frs. D–G contained relatively larger polar components with low Rf values ranging from approximately 0.2–0.5. It indicates that the TLC profiles of the saponin in frs. D–G were quite different from those of frs. A–C. The qualitative analysis using TLC plays an important role in the study of saponins. The sulfuric acid-based spray reagents are nonspecific for the detection of saponins (Kerem et al. 2005), while 1% cinnamaldehyde staining solutions are highly specific for steroidal saponins and produce green or violet spots. In this study, staining with 1% cinnamaldehyde solution revealed that each fraction contained more than three components (data not shown). Following TLC analysis and staining of frs. F and G with 50% sulfuric acid and 1% cinnamaldehyde, it was assumed that the major bioactive compound (Rf = 0.29) was asterosaponin (Fig. 2c) because the spots were visibly green. The saponin components had higher polarity in frs. D–G and were more active in cholesterol-binding ability tests than those with lower polarity (frs. A–C). The less polar fractions (frs. A–C) perhaps contained smaller saponins (Raphaela et al. 2014). It is noteworthy that the less polar frs. (A–C) were not interest in this study. The polarity of saponin varies based on their sugar units linked to its aglycone (Raphaela et al. 2014). The polar frs. (D–G) are associated with substantial cholesterol-binding ability, suggesting that the biological activity of saponins might be related to polarity.

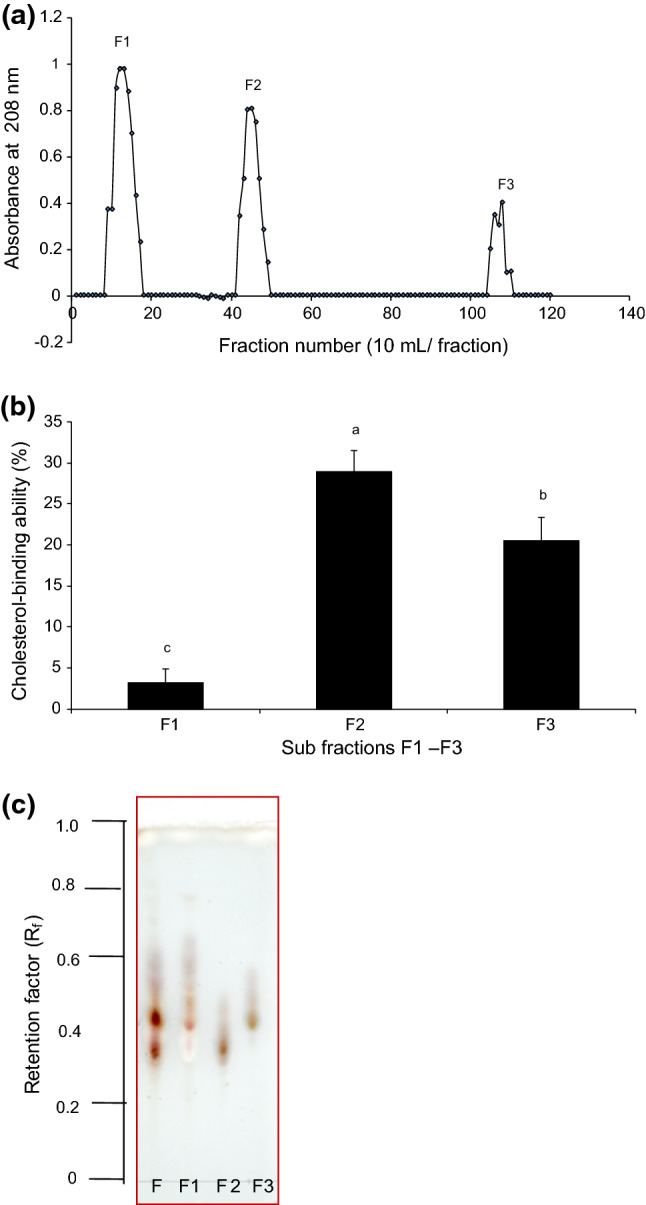

Isolation and identification of cholesterol-binding compounds

On the basis of the cholesterol-binding ability (Fig. 2b) and TLC results (Fig. 2c), fr. F was selected for structural analysis using silica gel column chromatography (Fig. 3a). Fraction F was separated into three sub-fractions, frs. F1–F3 by increasing polarity with stepwise gradient CHCl3:CH3OH:H2O. Cholesterol-binding substance was present in frs. F2 and F3, with a cholesterol-binding ability of 29% and 20%, respectively (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Silica gel column chromatogram of fr. F and cholesterol-binding abilities of sub-fractions. a Silica gel chromatogram for fr. F using silica column (1.5 × 100 cm eluted CHCl3:CH3OH:H2O [90:10:1 to 65:35:10]) for fr. F, b cholesterol-binding abilities obtained from the sub-fractions (designated fr. F1–F3) and c the TLC patterns for each sub-fraction

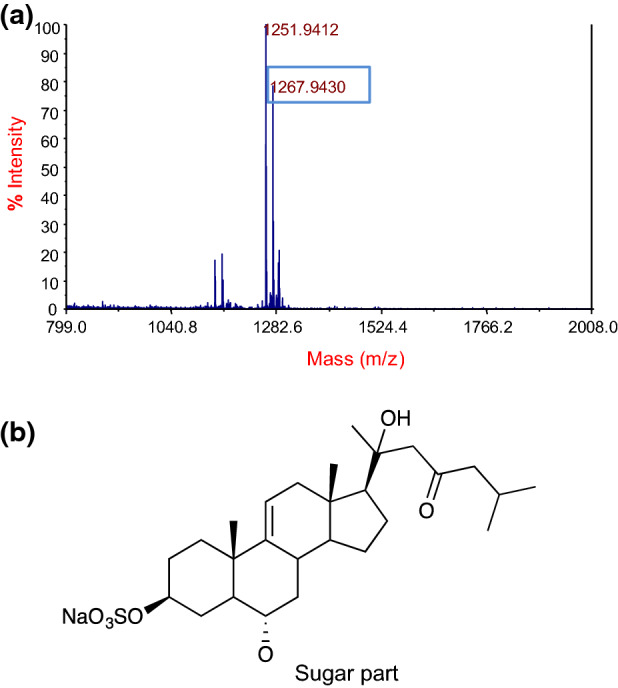

Based on the cholesterol-binding results, fr. F2 (Fig. 3c) was subjected to MALDI-TOF MS analysis in positive ion mode. The prominence of ions [M + Na]+ in MS analysis enables the analysis of saponins. The results indicate that the fraction was pure, which was consistent with the TLC pattern. A major intensity peak was observed and detected at m/z 1267.9 (Fig. 4a); however, it was difficult to obtain sufficient information about the aglycone or the type of esterification of the glucuronyl residue from MALDI-TOF MS analysis.

Fig. 4.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of sub Fr. F2 a and aglycone structure of asterosaponin (thornasteroside A) b

The presence of the saponin ion was confirmed by NMR structural analysis for the ion at m/z 1267.9 [M + Na]+ (Fig. 4a) and all the data from the NMR experiments are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The 1H and 13C NMR spectrum showed a typical pattern of a steroidal saponin with typical signals: two doublet methyl carbons (i.e., δC 22.5 at C-27 and δC 22.6 at C-26), three singlet methyl carbons (i.e., δC 13.6 at C-18, δC 19.4 at C-19, and δC 59.5 at C-17), a double bond (i.e., δC 144.6 at C-9 and δC 116.7 at C-11), and many oxygenated methane carbons between 60 and 80 ppm (Table 1). The 2D NMR (COSY, HMQC, and HMBC) and DEPT experiments suggested some partial structures of the isolated component. Briefly, the presence of five anomeric carbons (i.e., δC 102.4, δC 104.3, δC 104.5, δC 105.0, and δC 106.4) suggested the presence of five sugar units, which were identified as two quinovose, one galactose, one fucose, and one xylose (Table 2). The presence of a ketone carbon δC 211.8 at C-23 and a quaternary carbon δC 74.1 at C-20 with oxygen and selected HMBC correlations of protons surrounding these parts suggested the partial structures of the side chain part. Other HMBC correlations of methyl groups and an olefin proton suggested the aglycon part and HMBC correlations δH 4.80 (QuiI-1)/ δC 80.6 (C-6), and δH 3.79 (H-6)/ δC 105.0 (QuiI-1) suggested the binding position of a quinovose to aglycon at C-6 position. The linkage pattern of sugar units was confirmed by HMBC correlations of δH 3.80 (QuiI-3) with δC 104.3 (Xyl-1), δH 4.10 (Xyl-2) with δC 104.5 (QuiII-1), δH 4.19 (Xyl-4) with δC 102.4 (Gal-1), and δH 4.43 (Gal-2) with δC 106.2 (Fuc-1). Based on these spectral data, fr. F2 was identified as thornasteroside A with the aglycon part as shown in Fig. 4b. Other correlation data in 2D NMR supported the identification. The molecular formula of fr. F2 was interpreted to be C56H91O28SNa based on these NMR and MS data.

Table 1.

1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy data for the aglycone part of sub-fraction F2a,b and thornasteroside Ac

| Position | Fraction F2 | Thornasteroside Ac | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC and typea | δH and couplingb | δC and type | δH and coupling | ||||||||||

| 1 | 36.0 | CH2 | 1.35 | m; | 1.65 | m | 36.4 | CH2 | 1.39 | m; | 1.65 | m | |

| 2 | 29.5 | CH2 | 1.87 | m; | 2.78 | m | 29.9 | CH2 | 1.90 | m; | 2.82 | m | |

| 3 | 77.7 | CH | 4.89 | m | 77.9 | CH | 4.93 | m | |||||

| 4 | 30.8 | CH2 | 1.69 | m; | 3.48 | m | 31.2 | CH2 | 1.71 | m; | 3.51 | br | |

| 5 | 49.4 | CH | 1.48 | m | 49.8 | CH | 1.50 | m | |||||

| 6 | 80.6 | CH | 3.79 | m | 80.9 | CH | 3.81 | m | |||||

| 7 | 41.6 | CH2 | 1.32 | m; | 2.71 | m | 42.0 | CH2 | 1.31 | m; | 2.72 | m | |

| 8 | 35.3 | CH | 2.13 | m | 35.7 | CH | 2.11 | m | |||||

| 9 | 144.6 | C | – | 145.8 | C | – | |||||||

| 10 | 38.3 | C | – | 38.7 | C | – | |||||||

| 11 | 116.7 | CH | 5.23 | d | 117.1 | CH | 5.23 | ||||||

| 12 | 42.6 | CH2 | 2.05 | m | 2.29 | m | 42.8 | CH2 | 2.05 | br; | 2.28 | m | |

| 13 | 41.6 | C | – | 42.0 | C | - | |||||||

| 14 | 54.0 | CH | 1.28 | m | 54.4 | CH | 1.29 | m | |||||

| 15 | 23.6 | CH2 | 1.44 | m; | 2.23 | m | 23.7 | CH2 | 1.67 | m; | 2.26 | m | |

| 16 | 25.2 | CH2 | 1.27 | m; | 1.86 | m | 25.5 | CH2 | 1.26 | m; | 1.82 | m | |

| 17 | 59.5 | CH | 1.68 | m | 59.9 | CH | 1.67 | m | |||||

| 18 | 13.6 | CH3 | 1.03 | s | 14.0 | CH3 | 1.03 | s | |||||

| 19 | 19.4 | CH3 | 0.97 | s | 19.6 | CH3 | 0.97 | s | |||||

| 20 | 74.1 | C | – | 74.1 | C | – | |||||||

| 21 | 27.2 | CH3 | 1.58 | s | 27.4 | CH3 | 1.61 | s | |||||

| 22 | 55.1 | CH2 | 2.60 | d; | 2.80 | d | 55.3 | CH2 | 2.64 | d; | 2.82 | d | |

| 23 | 211.8 | C | – | 212.1 | C | – | |||||||

| 24 | 54.0 | CH2 | 2.36 | m; | 2.50 | m | 54.4 | CH2 | 2.40 | dd; | 2.48 | dd | |

| 25 | 23.5 | CH | 2.32 | m | 24.7 | CH | 2.24 | m | |||||

| 26 | 22.6 | CH3 | 0.91 | d | 23.0 | CH3 | 0.91 | d | |||||

| 27 | 22.5 | CH3 | 0.92 | d | 22.9 | CH3 | 0.91 | d | |||||

a Assingment based on the DEPT, HMQC and HMBC NMR data (150 MHz, pyridine-d5)

b Assingment based on the COSY, HMQC and HMBC NMR data (600 MHz, pyridine-d5)

c Data (pyridine-d5) provided from the literature by Hwang et al. (2014)

Table 2.

13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy data for the linked sugar chain part of sub-fraction F2a,b and thornasteroside Ac

| Position | Fraction F2 | Thornasteroside Ac | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC and typea | δH and couplingb | δC and type | δH and coupling | |||||||||

| QuiI-1' | 105.0 | CH | 4.80 | d | 105.6 | CH | 4.83 | d | ||||

| 2' | 74.9 | CH | 4.21 | m | 74.5 | CH | 4.03 | m | ||||

| 3' | 90.5 | CH | 3.80 | m | 90.5 | CH | 3.83 | t | ||||

| 4' | 75.5 | CH | 4.20 | m | 75.0 | CH | 3.58 | m | ||||

| 5' | 72.6 | CH | 3.62 | m | 72.4 | CH | 3.72 | m | ||||

| 6' | 18.5 | CH3 | 1.49 | m | 18.9 | CH3 | 1.60 | d | ||||

| Xyl-1′' | 104.3 | CH | 5.00 | d | 104.9 | CH | 5.05 | d | ||||

| 2′' | 81.7 | CH | 4.10 | m | 82.0 | CH | 4.13 | m | ||||

| 3′' | 76.7 | CH | 4.19 | m | 76.3 | CH | 4.22 | m | ||||

| 4′' | 79.5 | CH | 4.19 | m | 79.7 | CH | 4.23 | m | ||||

| 5′' | 64.6 | CH2 | 3.79 | m; | 4.49 | m | 65.0 | CH2 | 3.83 | m; | 4.51 | m |

| QuiII-1′'' | 104.5 | CH | 5.32 | d | 105.3 | CH | 5.34 | d | ||||

| 2′'' | 76.8 | CH | 3.62 | m | 76.6 | CH | 4.12 | m | ||||

| 3′'' | 77.0 | CH | 4.07 | m | 77.2 | CH | 4.12 | m | ||||

| 4′'' | 76.5 | CH | 3.62 | m | 75.9 | CH | 4.08 | m | ||||

| 5′'' | 73.6 | CH | 3.67 | m | 74.0 | CH | 3.71 | m | ||||

| 6′'' | 18.5 | CH3 | 1.70 | m | 18.3 | CH3 | 1.78 | d | ||||

| Gal-1′''' | 102.4 | CH | 4.97 | d | 102.8 | CH | 5.00 | d | ||||

| 2′''' | 83.5 | CH | 4.43 | m | 84.1 | CH | 4.49 | m | ||||

| 3′''' | 75.9 | CH | 4.04 | m | 75.4 | CH | 4.21 | m | ||||

| 4′''' | 69.4 | CH | 4.50 | m | 69.7 | CH | 4.52 | br | ||||

| 5′''' | 77.8 | CH | 4.03 | m | 77.4 | CH | 4.09 | m | ||||

| 6′''' | 61.9 | CH2 | 4.33 | m; | 4.40 | m | 62.3 | CH2 | 4.37 | dd; | 4.44 | m |

| Fuc-1′'''' | 106.4 | CH | 4.93 | d | 107.8 | CH | 4.86 | d | ||||

| 2′'''' | 74.1 | CH | 3.97 | m | 74.3 | CH | 4.46 | m | ||||

| 3′'''' | 76.2 | CH | 4.17 | m | 75.5 | CH | 4.01 | t | ||||

| 4′'''' | 73.5 | CH | 3.67 | m | 73.0 | CH | 3.96 | br | ||||

| 5′'''' | 72.1 | CH | 3.68 | m | 72.3 | CH | 3.64 | m | ||||

| 6′'''' | 17.9 | CH3 | 1.75 | m | 17.6 | CH3 | 1.46 | d | ||||

Qui I: quinovose 1, Qui II: quinovose 2, Gal: galactose, Fuc: fucose, Xyl: xylose

a Assingment based on the DEPT, HMQC and HMBC NMR data (150 MHz, pyridine-d5)

b Assingment based on the COSY, HMQC and HMBC NMR data (600 MHz, pyridine-d5)

c Data (pyridine-d5) provided from the literature by Hwang et al. (2014)

Thornasteroside A is one of the most widely distributed asterosaponins and has been isolated in 15 species from three major orders of Asteroidea (Hwang et al. 2014). Thornasteroside A consists of five types of sugar residues. The biological activities of saponins might be related to their carbohydrate moiety, although the mechanisms involved remain uncharacterized (D’Auria et al. 1993). The presence of these anomeric configurations anywhere in the sugar moiety is unfavourable for cholesterol-binding ability. Thus, the functional properties of saponins may be dependent on the position and length of the sugar residue. Thornasteroside A, a member of the asterosaponin family, exhibits cytotoxicity as well as anti-fungal, hemolytic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer activities (Hwang et al. 2014). These biological activities are recognized as a part of self-defense mechanism of starfish to dominate its ecological niche (Xiao and Yu 2013). A large number of saponins with different chemical structures have been isolated from nature. Variations of the aglycone structure and different combinations with sugar molecules make saponin a group of highly variable compounds, where each substance showing specific properties and biological activities. Starfish saponins are complex mixtures composed of different type’s aglycones and carbohydrate fractions. Therefore, in the present study, thornasteroside A was isolated to clarify its functional properties and cholesterol-binding ability in order to advanced utilization of starfish resources. Hence, there are significant opportunities for further research on the applications of saponin extracts from a diverse range of marine animal’s starfish.

Conclusion

We have been investigating the biological properties of various starfish extracts to exploit novel functions and pharmaceutical ingredients from underutilized starfish. In the present study, we examined the cholesterol-binding activity of extracts from seven species of starfish, found it in all specimens tested, and successfully isolated a cholesterol-binding substance from the A. amurensis extract. MALDI-TOF MS and NMR analyses demonstrated that the substance was identified as thornasteroside A, asterosaponin. Although the binding mechanism between thornasteroside A and cholesterol remains to be clarified, it is possible that saponin in starfish is applicable to some functional food or therapeutic uses.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Masaji Ko-uchi of the Kobe City Fisheries Co-operative Association, Japan, for supplying experimental specimens and Dr. Yuji Nagashima of Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology for helpful discussions. We also thank Mr. Akihito Katori of Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology for assistance with cholesterol-binding assay.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Farhana Sharmin, Email: ginisaz80@gmail.com.

Tomoyuki Koyama, Email: tskoyama@kaiyodai.ac.jp.

Hiroki Koyama, Email: hkoyam1@kaiyodai.ac.jp.

Shoichiro Ishizaki, Email: ishizak@kaiyodai.ac.jp.

References

- Andersson L, Bohlin L, Iorizzi M, Riccio R, Minale L, Moreno-López W. Biological activity of saponins and saponin-like compounds from starfish and brittle-stars. Toxicon. 1989;27:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(89)90131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin JM, Kuzina V, Andersen SB, Bak S. Molecular activities, biosynthesis and evolution of triterpenoid saponins. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:435–457. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz NO, Alnahdi HS. Potential impact of Panax ginseng against ethanol induced hyperlipidemia and cardiac damage in rats. Pakistan J Pharm Sci. 2018;31:927–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulier G, Van Dyck S, Gerbaux P, Eeckhaut I, Flammang P. Review of saponin diversity in sea cucumbers belonging to the family Holothuriidae. SPC Beche-de-mer Inf Bull. 2011;31:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cleamond DE, Arthur LD, Clarence RC. Effects of tomatine on the colorimetric determination of cholesterol by the zak procedure. Clin Chem. 1967;13:464–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchaine AJ, Miller WH, Stein DB. Rapid semi-micro procedure for estimating free and total cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1959;5:609–614. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/5.6.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Auria MV, Minale L, Riccio R. Polyoxygenated steroids of marine origin. Chem Rev. 1993;93:1839–1895. doi: 10.1021/cr00021a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Barky AR, Hussein SA, AlmEldeen AAE, Hafez YA, Mohamed TM. Saponins and their potential role in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Manag. 2017;7:148–158. [Google Scholar]

- EL-Farok DHM, EL-Denshry ES, Mahmoud M, Asaaf N, Emam M, Lipid lowering effect of Ginseng and Alpha-lipoicacid in hypercholesterolemic patients. Global J of Pharmacol. 2013;7:298–306. [Google Scholar]

- Eskandar M, Hossein K, Shahrzad P, Somayeh H. In-vitro Evaluation of Complex Forming Affinity of Total Saponins Extracted from Ziziphus spina-christi and Quillaja saponaria with cholesterol. RJPBCS. 2015;6:619–623. [Google Scholar]

- Gurfinkel DM, Rao AV. Soya saponins: The relationship between chemical structure and colon anticarcinogenic activity. Nutr Cancer. 2003;47:24–33. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc4701_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang IH, Kulkarni R, Yang HM, Choo SJ, Zhou W, Lee SM, Jang TS, Jeong GS, Chang HW, Na MK. Complete NMR assignments of under graded asterosaponins from Asterias amurensis. Arch Pharm Res. 2014;37:1252–1263. doi: 10.1007/s12272-014-0374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki S, Iwase M, Tanaka M. Enhancing effects of starfish Asterias amurensis saponin upon thermal aggregation of actomyosin from walleye pollack meat. Fish Sci. 1997;63:159–160. doi: 10.2331/fishsci.63.159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kabara JJ, Mclaughlin JT, Riegel CA. Quantitative microdetermination of cholesterol using tomatine as precipitating agent. Anal Chem. 1961;33:305. doi: 10.1021/ac60170a048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerem Z, German-Shashoua H, Yarden O. Microwave-assisted extraction of bioactive saponins from chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) J Sci Food Agric. 2005;85:406–412. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.1989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kubanek J, Whalen K, Engel S, Kelly S, Henkel T, Fenical W, Pawlik J. Multiple defensive roles for triterpene glycosides from two Caribbean sponges. Oecologia. 2002;131:125–136. doi: 10.1007/s00442-001-0853-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H, Li Y, Yamahara J, Yoshikawa M. Inhibition of gastric emptying by triterpene saponin, momordin Ic, in mice: roles of blood glucose, capsaicin-sensitive sensory nerves, and central nervous system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:729–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui Y, Kumagai H, Masuda H. Anti hypercholesterolemic activity of catechin-free saponin-rich extract from green tea leaves. Food Sci Technol Res. 2006;12:50–54. doi: 10.3136/fstr.12.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park HY, Kim JY, Kim HJ, Lee GH, Park JI, Lim CW, Kim YK, Yoon HD. Insecticidal and Repellent Activities of Crude Saponin from the Starfish Asterias Amurensis. J Fish Sci Technol. 2009;12:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Raphaela GB, Carmen LQ, Ílio MJ, Fernando AC. Fractionated extraction of saponins from Brazilian ginseng by sequential process using supercritical CO2, ethanol and water. J Supercrit Fluids. 2014;92:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2014.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- San M, Briones R. Industrial uses and sustainable supply of Quillaja saponaria (Rosaceae) saponins. Econ Bot. 1999;53:302–311. doi: 10.1007/BF02866642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz DP, Brewington CP, Bugwald HL. Rapid quantitative produce for removing cholesterol from butter fat. J Lipid Res. 1967;8:54–55. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)38942-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Hu S. Adjuvant activities of saponins from traditional Chinese medicinal herbs. Vaccine. 2009;27:4883–4890. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundfeld E, Yun J, Kochta M, Richardson T. Separation of cholesterol from butter oil using quillaja saponins. 1. Effects of pH, contact time and adsorbence. J Food Process Eng. 1993;32:191–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4530.1993.tb00316.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thao NP, Luyen BT, Kim EJ, Kang HK, Kim S, Cuong NX, Nam NH, Kiem PV, Minh CV, Kim YH. Asterosaponins from the starfish Astropecten monacanthus suppress growth and induce apoptosis in HL-60, PC-3, and SNU-C5 human cancer cell lines. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37:315–321. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b13-00705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincken JP, Heng L, de Groot A, Gruppen H. Saponins, classification and occurrence in the plant kingdom. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:275–297. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windaus A. On the detoxification of saponin by cholesterol. Chem Ber. 1909;42:238. doi: 10.1002/cber.19090420138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G, Yu B. Total synthesis of starfish saponin Goniopectenoside B. Chemistry A European Journal. 2013;19:7708–7712. doi: 10.1002/chem.201301186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasumoto T, Tanaka M, Hashimoto Y. Distribution of saponins in echinoderms. Bull Japan Soc Sci Fish. 1966;32:673–676. doi: 10.2331/suisan.32.673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HL, Harding SV, Marinangeli CP, Kim YS, Jones PJ. Hypocholesterolemic and anti-obesity effects of saponins from Platycodon grandiflorum in hamsters fed zxdatherogenic diets. J Food Sci. 2008;73:195–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]