Abstract

Malaria, one of the longest-known vector-borne diseases, poses a major health problem in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Its complexity is currently being exacerbated by the emerging COVID-19 pandemic and the threats of its second wave and looming third wave. We formulate and analyze a mathematical model incorporating some epidemiological features of the co-dynamics of both malaria and COVID-19. Sufficient conditions for the stability of the malaria only and COVID-19 only sub-models’ equilibria are derived. The COVID-19 only sub-model has globally asymptotically stable equilibria while under certain condition, the malaria-only could undergo the phenomenon of backward bifurcation whenever the sub-model reproduction number is less than unity. The equilibria of the dual malaria-COVID19 model are locally asymptotically stable as global stability is precluded owing to the possible occurrence of backward bifurcation. Optimal control of the full model to mitigate the spread of both diseases and their co-infection are derived. Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle is applied to establish the existence of the optimal control problem and to derive the necessary conditions for optimal control of the diseases. Though this is not a case study, simulation results to support theoretical analysis of the optimal control suggests that concurrently applying malaria and COVID-19 protective measures could help mitigate their spread compared to applying each preventive control measure singly as the world continues to deal with this unprecedented and unparalleled COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Introduction

Malaria, a mosquito-borne infectious disease, alone or in combination with other diseases kills millions of people in tropical and subtropical regions, causing an enormous impact on health systems and economies [1], [2]. Humans acquire malaria infection from infected female Anopheles mosquitoes during blood feeding, especially from Plasmodium falciparum. The chain of transmission can be broken through use of mosquito treated nets and anti-malarial drugs as well as other control strategies, see [1], [3] and the references therein. The emergence of malaria drug resistance and the lack of an effective and safe vaccine have increased the complexity of mitigating malaria burden (morbidity and mortality) [4]. Malaria prevention control is mainly based on the use of preventive measures (such as mosquito-reduction strategies and personal protection against mosquito bite).

The outbreak that initially appeared in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, in December 2019 of the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) known as COVID-19 has spread rapidly around the world, evolving into a pandemic and causing major public health concerns [5], [6], [7]. Its symptoms from mild to severe respiratory infections last 2–14 days include cough, fever, weakness, and difficulty to breath. Coronaviruses can be extremely contagious and spread easily from person to person. COVID-19 transmission routes contain direct transmission, such as close touching and indirect transmission consisting of the air by coughing and sneezing, even if contacting some contaminated surfaces by virus particles [8]. COVID-19 pandemic is having a massive impact on populations and economies around the world, placing an extra burden on health systems around the planet [9]. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa which accounts for more than 90% of global malaria cases and deaths, are facing a double challenge of protecting their citizens against both malaria and the emerging COVID-19. National health systems response is understandably focused on the COVID-19 pandemic, and there are resulting repercussions on already overstretched and under-resourced health systems [10]. Gutman et al., [11] noted that co-infections of malaria and COVID-19 are likely in malaria prevalent countries. In fact, there is a wide geographical overlap of the distribution of malaria within large regions and the current COVID-19 pandemic. Malaria and COVID-19, two major diseases with overlapping distributions could thus form a deadly cycle of co-infection, and this symbiotic relationship between the two diseases could be a double blow in tropical and sub-tropical regions (low and middle income countries) where malaria has been endemic because of the high incidence of malaria and massive impact of COVID-19 on availability of key malaria control interventions.

Mathematical models have been used to provide framework for understanding the dynamics of infectious diseases. Models of COVID-19 transmission dynamics are flourishing in the literature [12], [13], [14], [15], and the reference therein. Weiss et al., [16] noted the huge potential impact of COVID-19 related disruptions in malaria intervention and control strategies. With malaria heavily concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa where cases and deaths associated with COVID-19 have been reported, Sherrard-Smith et al., [17] used COVID-19 and malaria transmission models to estimate the impact of disruption of malaria prevention activities and other core health services under different COVID-19 epidemic scenarios. They concluded that substantial progress made in reducing the burden of malaria could be jeopardized as unprecedented measures to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 pandemic are affecting the availability of key malaria control interventions and other health sectors due to immense restrictions [17]: movement, travel, cancellation of large events, school, workplace and major shopping centers closure [18]. As the COVID-19 pandemic spreads rapidly around the globe, there is an urgent need to aggressively tackle the novel coronavirus while ensuring that other diseases such as malaria, are not neglected [9], because the consequences could be dire in vulnerable populations [19]. Also, as malaria programmes are being severely affected in many ways by COVID-19 [19], Hogan et al., [20] noted that maintaining the most critical prevention activities and health-care services for malaria could substantially reduce the overall impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

COVID-19 affects malaria in one way or the other, for example, lock-downs and other measures introduced to slow transmission of COVID-19 have interrupted access to routine care and prevention services, thereby affecting the extent to which seasonal malarial chemoprevention, and routine case management such as testing, treatment and tracking are possible [10]. Also, widespread use of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (which affects vectors of the malaria parasites) are likely to have been interrupted as a result of interruption of planned net campaigns [20], as well as disruptions to health services and a drop in outpatient visits. Herein, we only purposively consider non-therapeutic measures for reducing the spread of malaria and COVID-19 because of the ease of implementation of these selective and sustainable personal protection measures such as insecticide-treated materials against mosquito bites, face masks, isolation and hand washing with soap against COVID-19. However, we note that other intervention measures such as draining of wetlands and standing waters, transgenic mosquitoes, gametocytocidal drugs, chemoprophylaxis (though is weakly effective due to lack of patient compliance and drug resistance of Plasmodium falciparum) are extremely important effective public health measures [2]. Compounding these issues, the symptoms of both malaria and COVID-19 include fever, which poses diagnostic and management dilemmas where testing facilities are not optimal. In fact, dengue, malaria and COVID-19 may share clinical and laboratory features [21]. While continued malaria prevention and treatment programs will be essential to reduce pressure on health systems during the COVID19 pandemic, the presence of these two diseases in the same geographical area could lead to a deadly cycle of co-infection [10]. Consequently, enhancing surveillance platforms to investigate whether malaria and COVID-19 are syndemics (synergistic epidemics) as well as determining the rates of possible co-infection could help mitigate the potential impact of their co-infections [11].

The development of mathematical models has been very useful in our understanding of the dynamics of infectious diseases. In the context of diseases, Daniel Bernoulli in 1760 proposed a mathematical model of disease propagation and showed the efficiency of the preventive inoculation technique against smallpox [22]. Later on, Kermack and McKendrick extended this Susceptible-Immune model to a Susceptible-Infected-Recovered () model [23], [30]. Over the years, several sophisticated mathematical models of disease dynamics including co-infection models have appeared in the literature. While mathematical models being proposed to describe the dynamics of populations and their interactions and forecast the dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic are flourishing in the literature [24], it is our view and to the best of our knowledge that this study represents the very first modeling work that provides an in-depth analysis of the qualitative dynamics of COVID-19 and malaria co-infection and the optimal control strategies using non therapeutic measures. Thus, we formulate and rigorously analyze qualitatively a mathematical model for COVID-19 and malaria co-infection, which incorporates the key epidemiological and biological features of each of the two diseases. Optimal control is carried out using Pontragyn’s maximum principle [25].

The paper is organized as follows. The proposed model is formulated in Section 2. The sub-models for COVID-19 and malaria only are presented and theoretically analyzed in Sections 3.1 and 3.2, respectively. The analysis of the full COVID-19 and malaria co-infection model is carried out in Section 3.3. By applying Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle which uses both Lagrangian and Hamiltonian, optimal control of the full model to mitigate the spread of the two diseases is presented in Section 3.4. Numerical simulations performed to support theoretical results are presented in Section 4 and Appendix A, while Section 5 is the conclusion.

2. Model formulation

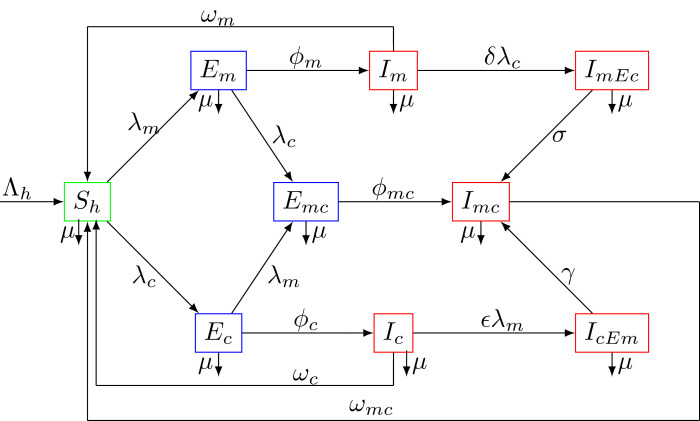

Motivated by the empirical observation that compartmental epidemiological models have played a significant role in the development to better understand the mechanism of epidemic transmission and the various preventive strategies used against it [26], we consider a deterministic mathematical model which uses ordinary differential equations. The human population at time denoted by is divided into sub-populations of susceptible individuals , individuals exposed to malaria only , individuals infected with malaria only , individuals exposed to COVID-19 only , infected individuals with COVID-19 only , individuals exposed to malaria and COVID-19 , individuals infected with malaria and exposed to COVID-19 , individuals infected with COVID-19 and exposed to malaria , and individuals infected with both malaria and COVID-19 . The total human population is given by

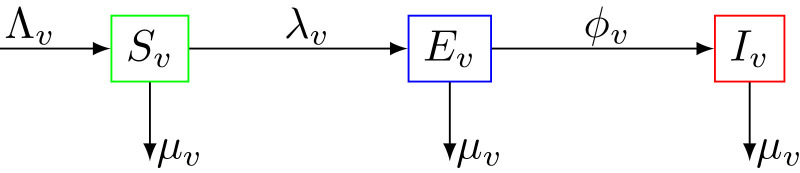

While anopheles mosquitoes go through four stages in their life cycle: egg, larva, pupa, and adult, in what follows, we consider the adult mosquitoes stage only. Mosquitoes, whatever their status are subject to a natural death (due to their finite life span), which occurs at a rate . The total vector (mosquito) population at time , denoted by , is sub-divided into susceptible mosquitoes , mosquitoes exposed to the malaria parasite , and infectious mosquitoes . The total mosquito population is given by

For simplicity of notations, we will subsequently drop the time in the model variables.

From the model flow diagrams of the disease transmission Figs. 1 and 2 , we derive the following system of nonlinear differential equations

| (1) |

with initial conditions

| (2) |

where

The parameter is the biting rate of female mosquitoes and , , represent respectively the probability for a human to be infected after effective contact with corona virus, the probability for a human to be infected with malaria from a bite of an infected mosquito and the probability for a mosquito to be infected after a blood meal from an infected human. The functions and represent the forces of infection. Because the number of contacts made by an infective per unit time should be limited, or should grow less rapidly as the total population size increases, the forces of infection considered are of standard incidence type [27]. The modification parameters and () are the enhancement factors accounting for the relative infectiousness of individuals respectively acquiring COVID-19 following malaria infection or acquiring malaria following COVID-19 infection.

Fig. 1.

Compartment diagram of the human component of the model.

Fig. 2.

Compartment diagram of the mosquito component of the model.

It is assumed that personal protection against COVID-19 is adopted in the community. Implementation of these intervention preventive measures could include wearing facial mask, social/physical distancing, hydro alcoholic gel, hand washing with soap and self-isolation. The effect of personal protection is modeled by the factor , where is the efficacy of personal protection strategy adopted,and is the fraction of the community employing it (compliance), where means compliance and represents no compliance at all. The model parameters, their description, values and sources are provided in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Fundamental model parameter.

| Parameter | Description | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| human | |||

| Recruitment rate of the host population | [42], [48] | ||

| Progression rate from exposed to infectious malaria state | [53] | ||

| Progression rate from exposed to infectious COVID-19 state | [49] | ||

| Fraction of individuals moving to the co-infection class | Assumed | ||

| Recovery rate of malaria infected individuals | [48] | ||

| Recovery rate of COVID-19 infected individuals | [50] | ||

| Recovery rate of malaria and COVID-19 infectious individuals | Assumed | ||

| Death rate of the host population | [42], [48] | ||

| Enhancement factor of acquiring COVID-19 following malaria infection | [1], [3] | ||

| Enhancement factor of acquiring malaria following COVID-19 infection | [1], [3] | ||

| COVID-19 infection rate of individuals already infected with malaria | Assumed | ||

| Malaria infection rate of individuals already infected with COVID-19 | Assumed | ||

| Fraction of individuals employing personal protection | Variable | ||

| Efficacy of personal protection | Variable | ||

| Number of female mosquito bites per day | [51] | ||

| Malaria transmission probability per mosquito bite | [34] | ||

| COVID-19 transmission probability per contact | 0.4531 | [52] | |

| Mosquitoes | |||

| Recruitment rate of vectors | [48] | ||

| Progression rate from exposed to infectious class | [1] | ||

| Natural death rate of vectors | [42], [48] | ||

| Transmission probability in vectors from infected humans | [53] |

3. Model analysis

Two sub-models, namely: malaria only and COVID-19 only sub-models are first considered.

3.1. COVID-19 only model

By setting we obtain the following COVID-19 only model.

| (3) |

where is the force of infection and . By adding up all the equations of the system (3), the total human population is given by

| (4) |

The given initial conditions (2) ensure that Thus, the total human population is positive and bounded for all finite time Solving the differential Eq. (4), we have

| (5) |

As , we obtain . From the theory of differential equations [28], [29], in the region

all solutions of the COVID-19 only model autonomous system (3) starting in remain in for all . This implies that is positively invariant and attracting [35]. Thus, the model (3) is mathematically and epidemiologically well-posed, and it is sufficient to study its dynamics in [1], [3].

3.1.1. Stability of the disease-free equilibrium

The disease-free equilibrium (DFE) of the COVID-19 only model system (3) is obtained by setting each of the system of model system (3) to zero. Also, at the DFE, there are no infections and recovery. Thus, the DFE of the COVID-19 only model (3) is given by

| (6) |

The linear stability of is established using the next generation operator method on the model system (3). Using the notations of [31], the matrices and for the new infection terms and the remaining transfer terms are given by

and

The basic reproduction number of the COVID-19 only model (3) is the dominant eigenvalue of the next generation matrix given by

| (7) |

The basic reproduction number is defined as the expected number of secondary cases generated by one infected individual during its entire period of infectiousness in a fully susceptible population.

From Theorem 2 of [31], the following result follows.

Lemma 3.1

The disease-free equilibriumof the COVID-19 only model system(3)is locally asymptotically stable ifand unstable otherwise.

Proof

The stability of is obtained from the Routh–Hurwitz criterion for stability, which states that the equilibrium is stable if the roots of the characteristic polynomial are all negative. For , the Jacobian matrix of the system is obtained as

The characteristic polynomial is given by

(8) where After some little algebraic manipulations, one notes that all the eigenvalues of the characteristic Eq. (8) have negative real parts if . Hence, the DFE of the COVID-19 only model system (3) is locally asymptotically stable when .

□

3.1.2. Stability of endemic equilibrium

We now explore the existence of endemic equilibrium of the COVID-19 only model system (3). The endemic equilibrium of system (3) is , where

From Theorem 2 of [31], the endemic equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable if and unstable otherwise. Global stability of the model equilibria implies the model does not exhibit the phenomenon of backward bifurcation where co-existence of both a stable disease-free equilibrium with a stable endemic equilibrium cannot hold, Mtisi et al. [1], Mukandavire et al. [3]. It is important to note that although the disease-free equilibrium interchanges its stability with the endemic equilibrium as the threshold parameter is varied, we wish to investigate the direction of the bifurcation (forward/transcritical bifurcation or backward/subcritical bifurcation).

We use the centre manifold theory as described in Castillo-Chavez and Song [32]. Let The model 3 can be rewritten in the form , with , that is

| (9) |

The Jacobian of the system (9) at the DFE is given by

Choosing as the bifurcation parameter and setting , we obtain

| (10) |

The transformed system (9), with , has a non-hyperbolic equilibrium point such that the linear system has a simple eigenvalue with zero real part and all other eigenvalues have negative real parts. Hence, the centre manifold theory [32] can be used to analyze the dynamics of the model (9) near . By using the notation in Castillo-Chavez and Song [32], we proceed as follows.

The right-eigenvector associated with the zero eigenvalue of such that at is given by

Similarly, the left-eigenvector

| (11) |

of such that

associated with the zero eigenvalue is given by

The right-eigenvector and the left-eigenvector must satisfy the condition That is,

To determine the direction of the bifurcation, we compute and determine the sign of the parameters and . At the DFE, the bifurcation coefficient is given by

The bifurcation coefficient is given by

Because is negative and since , the parameter is positive, and by Theorem 4.1 in Castillo-Chavez and Song [32], the COVID-19 only model system (3) does not exhibit the phenomenon of backward bifurcation at . Hence, the following result.

Lemma 3.2

The unique endemic equilibriumof the COVID-19 only model system(3)is globally asymptotically stable if.

Global stability implies that the classical requirement of having , is a necessary and potentially sufficient condition for disease control.

3.2. Malaria-only model

Malaria, caused by mosquito-borne hematoprotozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium is an important health problem threatening a large proportion of the wold’s population. It is transmitted to humans through the bites of infectious female mosquitoes. From the model system (1), the malaria only model which includes critical features of host-vector-parasite interactions is obtained by setting . The force of infection which depends on average number of mosquito bites and on the transmission probability per bite is assumed to be normalized by the total human population [33] and is given as .

Thus, the malaria only model is given by the following system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations.

| (12) |

where and

The feasible region for the model system (12) is

which is positively invariant and attracting, that is, solution starting in will remain in for all time . Thus, it is sufficient to consider the dynamics of the model system (12) in ).

3.2.1. Stability of the disease-free equilibrium

The DFE of the malaria only model (12) is given by

| (13) |

Using the next generation matrix operator method in van den and Watmough [31], the associated next generation matrix is given by

| (14) |

and the rate of transfer of individual to the compartments is given by

Hence, the new infection terms and the remaining transfer terms are respectively given by

and

The dominant eigenvalue or spectral radius of the next generation matrix which represents the basic reproductive number is given by

| (15) |

Using Theorem 2 of [31], we establish the following result.

Theorem 3.1

The DFE of the malaria-only model(12)is locally asymptotically stable if, and unstable otherwise.

3.2.2. Existence of the endemic equilibrium of the malaria-only model

Solving the malaria-only model at an arbitrary equilibrium denoted by , we obtain

| (16) |

where and

After some little algebraic manipulations, we obtain

| (17) |

Recall

| (18) |

From Eqs. (17) and (18), we obtain

After some little rearrangements, we obtain the following equation

Thus, or

| (19) |

Eq. (19) can be written as

which can be rearranged as

Let , and since , then,

Setting , we have

| (20) |

So,

| (21) |

Hence, we have established the following result.

Theorem 3.2

The malaria-only model system(12)has precisely one unique endemic equilibrium if.

3.2.3. Existence of backward bifurcation

Following the same approach as in Section 3.1.2, we investigate the global stability of the malaria-only model (12) using the center manifold approach [32].

Let so that and Further, by using vector notation , the malaria-only model (12) can be written in the form with as follows

| (22) |

where

Next, we evaluate the Jacobian of the system (22) at the DFE , denoted by given by

Choose as the bifurcation parameter, then setting gives

| (23) |

It follows that the Jacobian () of 22 at the DFE, with has a simple zero eigenvalue (with all other eigenvalues having negative real part). Hence, the Centre Manifold theory [34] can be used to analyze the dynamics of the malaria-only model (12). Following the approach in van den and Watmough [31], Castillo-Chavez and Song [32], Carr [34], Dushoff et al. [36], the right-eigenvector associated with the zero eigenvalue of such that at is given by

Similarly, the left-eigenvector of such that associated with the zero eigenvalue is given by

The right-eigenvector and the left-eigenvector need to satisfy the condition The bifurcation coefficient at the DFE is given by

The second bifurcation coefficient is given by

Since the sign of determines the direction of the bifurcation, it follows from Theorem 4.1 in Castillo-Chavez and Song [32] that the malaria-only model (22) undergoes the phenomenon of backward/subcritical bifurcation at whenever both and

| (24) |

This result is summarized below.

Theorem 3.3

Since, if, the malaria-only model(12)will undergo a backward/subcritical bifurcation at. If, the the malaria-only model(12)will undergo a forward/transcritical bifurcation at.

The public health implication of this result when a backward/subcritical bifurcation occurs is that the co-existence of a stable disease-free equilibrium with a stable endemic equilibrium is an epidemiological situation where although necessary, having the basic reproduction number less than unity is no longer sufficient for disease elimination [1], [3].

3.3. Malaria-COVID-19 model

The feasible region for system (1) is given by

with and are as defined in the previous sections. It can be shown following the approach in Mtisi et al. [1], Mukandavire et al. [3] that all solutions of the the co-infection malaria-COVID-19 model system (1) with non negative initial conditions remain non negative for all time . Also, from the theory of permanence [35], all solutions on the boundary of eventually enter the interior of . Thus, is positively-invariant and attracting under the flow induced by the system (1)

3.3.1. Stability of the disease-free equilibrium

The disease-free equilibrium of the malaria-COVID-19 1 is given by

| (25) |

Having derived the basic reproduction numbers for the COVID-19 only and malaria only sub-models using the next generation method in van den and Watmough [31], the associated reproduction number for the full model system (1) is given by

| (26) |

The following result follows from Theorem 2 in van den and Watmough [31].

Theorem 3.4

The DFE of the malaria-COVID-19 model(1)is locally asymptotically stable if the threshold parameter, and unstable if.

Since the malaria-only model (12) may undergo the phenomenon of backward bifurcation, the full malaria-COVID19 model (1) will also undergo backward bifurcation under the same conditions when the bifurcation parameters and [1], [3]. Using the centre manifold theory described in Castillo-Chavez and Song [32], the following result holds.

Theorem 3.5

If the bifurcation parametersand, the full model system(1)will undergo the phenomenon of backward/subcritical bifurcation at.

For the proof, see [1], [3], [47]. Note that the occurrence of backward bifurcation precludes the global asymptotic stability of the model’s equilibria. That is, both the DFE and endemic equilibria can only be locally asymptotically stable, but not globally.

3.4. Optimal control model

We investigate the impact of implementing non pharmaceutical interventions to prevent mosquitoes bites such as the use of insecticide-treated nets and to protect oneself again corona virus such as facial mask, and hand-washing with soap. We introduce into our proposed malaria-COVID-19 model (1) a set of time-dependent control variables where

-

a)

represents the use of personal protection measures to prevent mosquitoes bites during the day and the night such as the use of insecticide-treated nets, application of repellents to skin or spraying of insecticides, and

-

b)

represents the use of personal protection measures to protect oneself again corona virus such as facial mask, hydro alcoholic gel, hand-washing with soap.

The malaria-COVID-19 model with optimal control consists of the following non-autonomous system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations.

| (27) |

with initial conditions given by

| (28) |

Subject to the model system (27) and suitable initial conditions, we examine an optimal control problem with control such that the optimal control function

with the set of admissible controls, where

The optimal system is then developed to meet the necessary conditions satisfying Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle [25], which determines optimal control of the malaria-COVID-19 co-infection. Thus, to minimize the number of malaria and COVID-19 infections, we consider an optimal control function given by

| (29) |

where in the objective cost functional (29), , and are positive constants representing the weight that balance off the infected human population to malaria, infected human population to COVID-19 and co-infected human population to both malaria and COVID-19, respectively, while represents the weight constant of the total vector population, and are respectively weight constants for personal protection measures to prevent mosquitoes bites and personal protection measures to protect oneself again corona virus. The terms and describe the costs associated with the prevention of vector-human contacts and contact with corona virus. We chose a quadratic control function [37] because the positive balancing cost factors transfer the integral into monetary quantity over a finite period of time, while the nonlinearity of the control efforts is chosen for technical reason as this allows the Hamiltonian to attain its minimum over the admissible control set at a unique point [38]. We note however that the effects of varying the form of the objective functional have been considered in Joshi et al. [39], Saldana et al. [40]. Next, we prove the existence of an optimal control for system (27) and then derive the optimality system.

Theorem 3.6

Consider the objective functionalgiven by Eq.(27), withsubject to the constraint state system(1). There existssuch that

To derive the necessary conditions that the two controls and corresponding states must satisfy, we apply Theorem 5.1 (Pontryaginȉs Maximum Principle [25]) in Fleming and Rishel [41] to develop the optimal system for which the necessary conditions that must be satisfied by an optimal control and its corresponding states are derived. In fact, Theorem 1 in Agusto [42] which is based on the boundedness of solution of model system (1) without control variables ensures the existence of the optimal control while the existence of an optimal control with a given control pair follows from Fleming and Rishel [41], and Carathodory’s existence Theorem [43]. To convert the state system (27) and objective function (29) into a point-wise minimized problem, we define the Hamiltonian function for the optimal control system (27) as

| (30) |

where are the adjoint variables or co-state variables. The following result presents the adjoint system and control characterization.

Theorem 3.7

Given an optimal control, and corresponding state solutions

of the corresponding state system(1), there exist adjoint variables,, satisfying

(31) The controlsandsatisfy the optimality condition

(32)

Proof

The differential equations governing the adjoint variables are obtained by differentiation of the Hamiltonian function, evaluated at the optimal control. Then, the adjoint system can be written as

with zero final time conditions (transversality) . Replacing the derivatives of with respect to in the above equations, we obtain the optimality condition (32). The optimal conditions for the Hamiltonian are given by or equivalently

From the above equations, we obtain

Thus, and satisfies (32). □

4. Numerical simulations

To illustrate some of the analytical results in the previous sections, several numerical simulations are carried out. We consulted a wide range of literature to find relevant model parameter values listed in Table 1. Whenever parameter values were not available in the literature, we assume realistic values for the purpose of illustration. Using the default parameter values in Table 1, numerical simulations are provided to support the analytical results. Our focus is on investigating the effect of optimal non-pharmaceutical control strategies on the transmission dynamics of malaria and COVID-19 co-infection.

An iterative fourth-order Runge–Kutta integration scheme is employed to solve the model system (27) and the adjoint system (31). We also assumed, for illustrative purposes that the weight factor values . The positive constants , and represent the weight that balance off the infected human population to malaria, infected human population to COVID-19 and co-infected human population to both malaria and COVID-19, while represents the weight constant of the total vector population, and are respectively the weight constants for personal protection measures to prevent mosquitoes bites and personal protection measures to protect oneself again corona virus. Finally, following the biological interpretation of our system, that is all model and parameter values are non-negative, for illustrative purpose, we consider the following initial conditions . These assumed values have been intuitively chosen to theoretically investigate the effects of the preventive control measures to mitigate the spread of malaria and COVID-19 co-infection. Because this is a theoretical analysis and not a case study, our model parameter values do not necessarily have a significant meaning attached [44], [45], [46], [47]. However, based on the assumption that high cost could potentially be associated with COVID-19 prevention, has been made slightly greater than , while the two control strategies are all constrained between zero and one, that is, . For instance, if , it implies no malaria prevention such as insecticide treated bednets are provided, and implies there is at least some malaria prevention measures being applied in the population. Table 1 provides all the model parameter values used for the simulations.

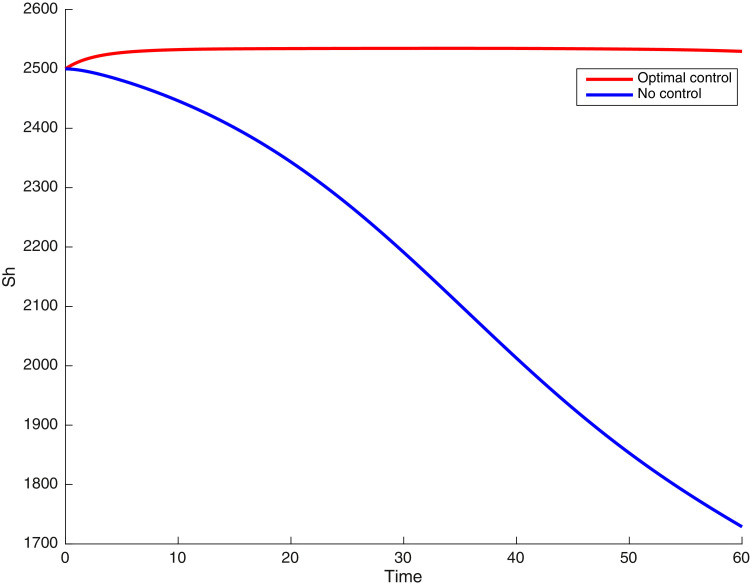

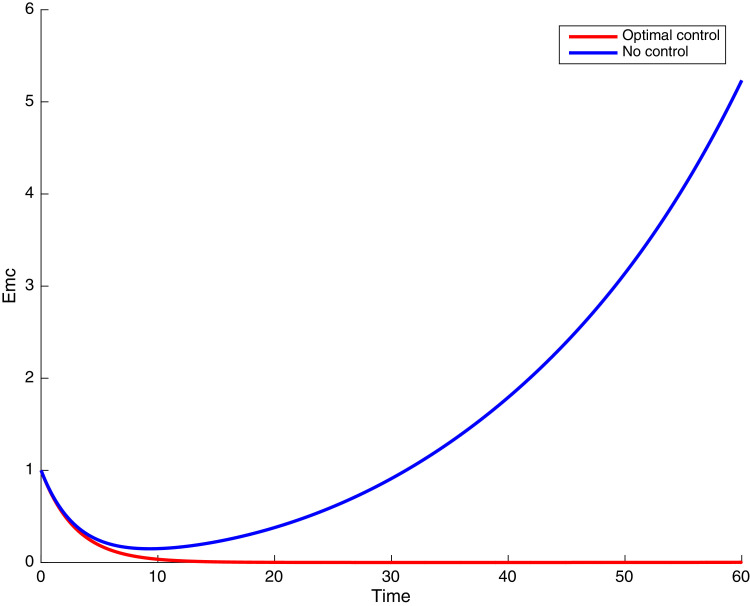

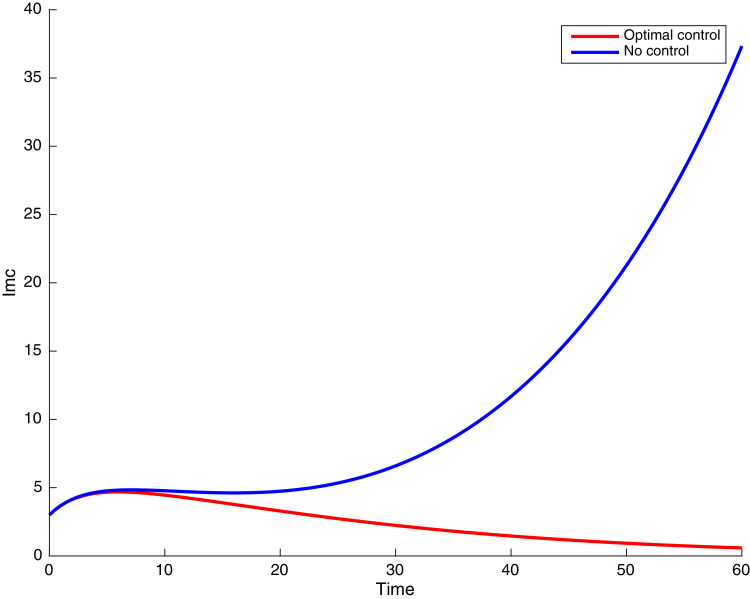

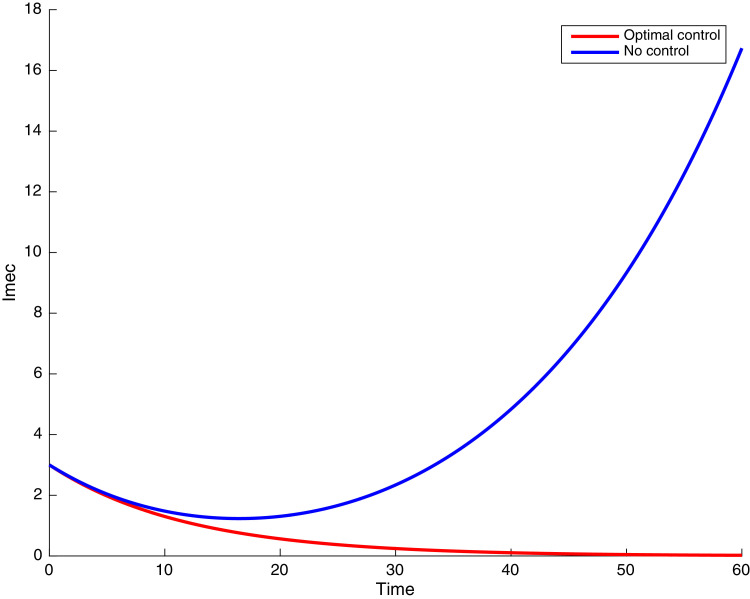

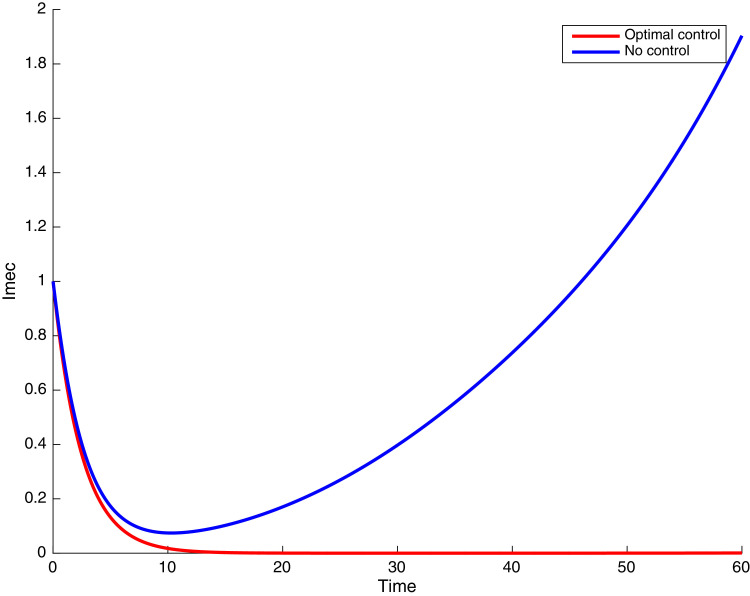

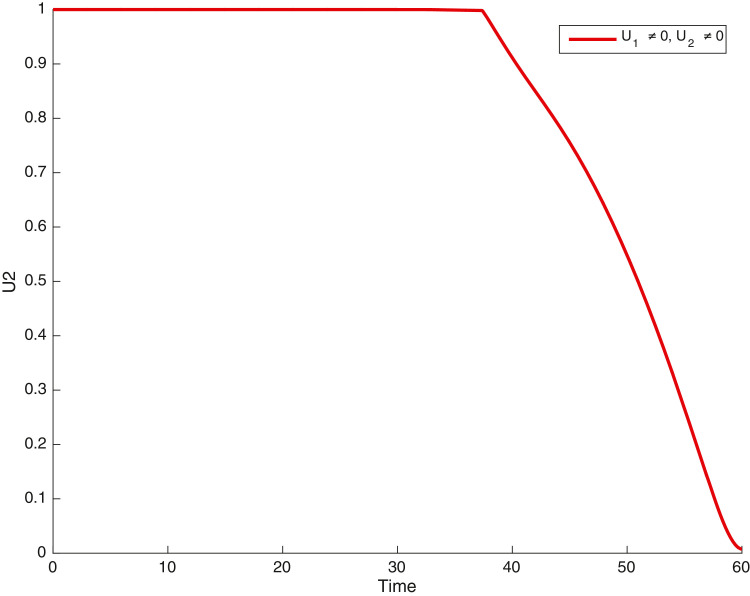

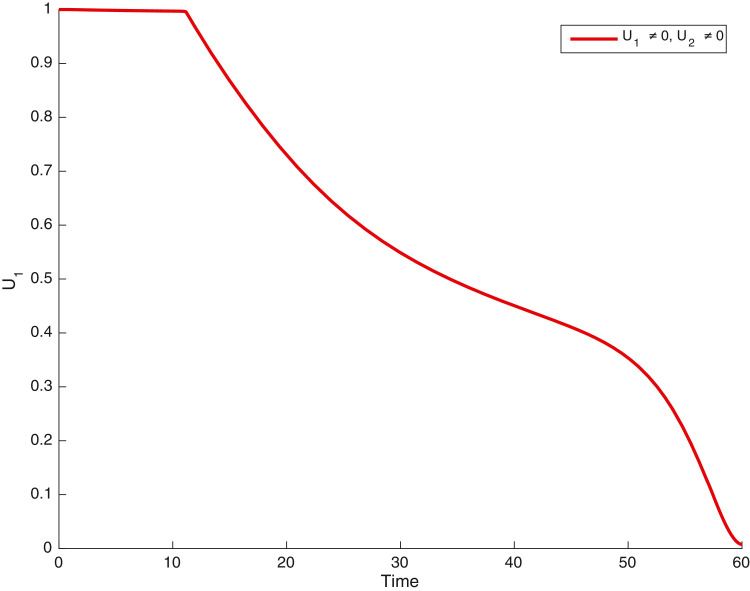

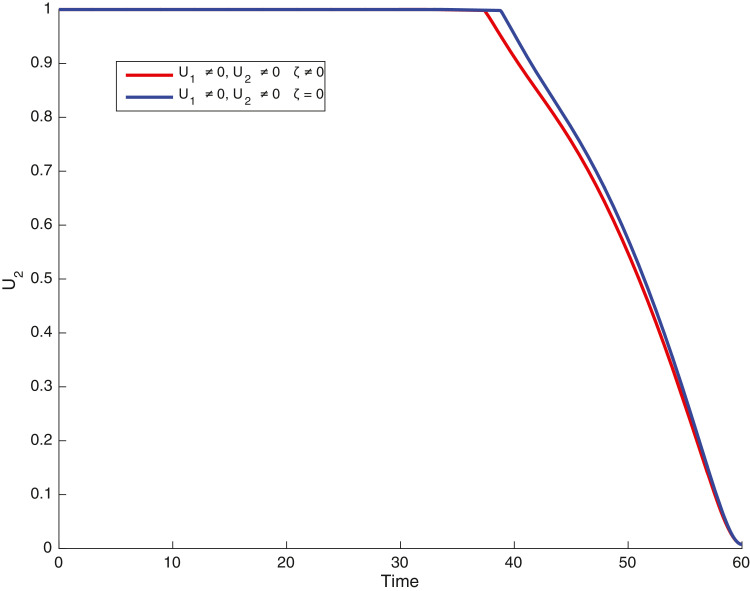

4.1. Simulations when both malaria and COVID-19 preventions are concurrently implemented; and

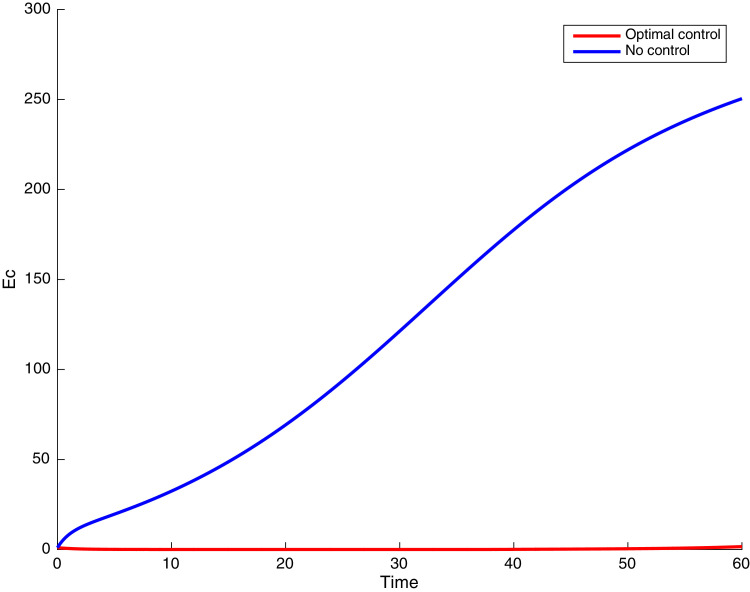

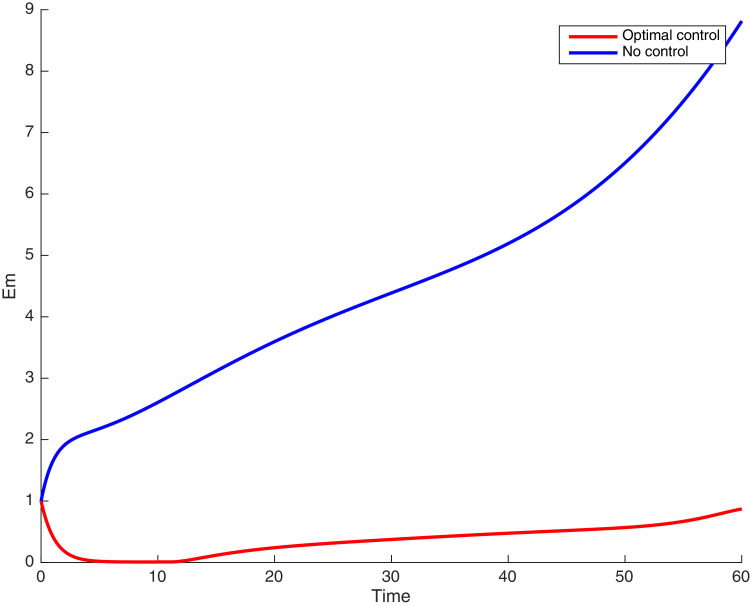

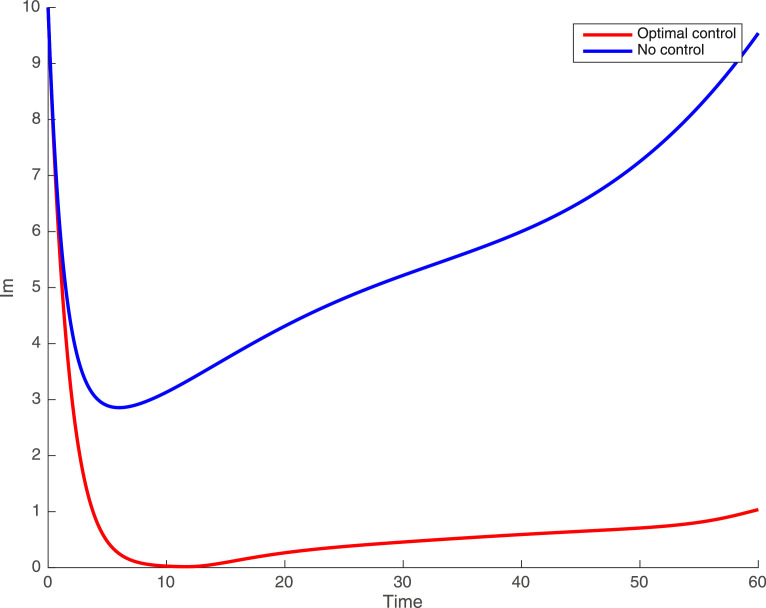

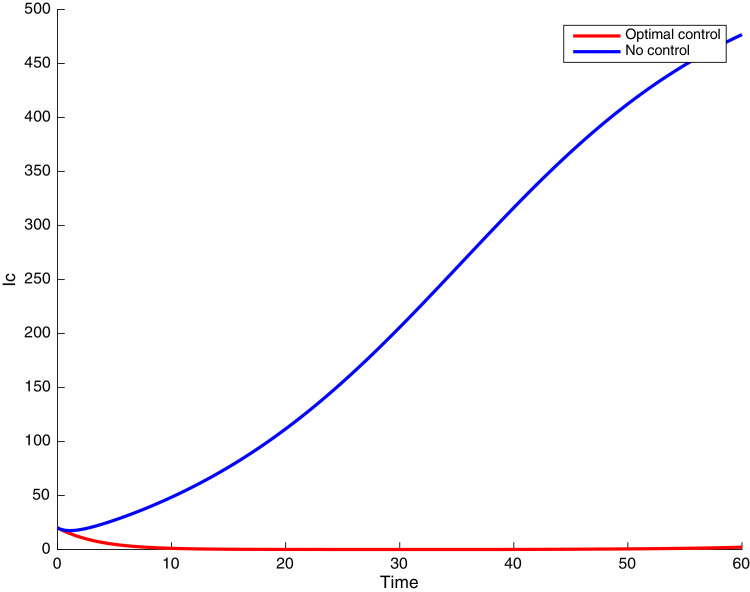

In this case, the control related to prevention against malaria and the control for prevention against COVID-19 are used to minimize the objective function . In Fig. 3 , there is a depletion of the number of susceptible humans when there is no controls and an increase in the number of susceptible humans when preventive measures are applied. In fact, from Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10, Fig. 11 , we observe that the controls and result in a decrease of the number of infected and infectious to malaria only, COVID-19 only and malaria and COVID-19 co-infection, while there is an increase in the number of infected and infected humans without control. The controls and are graphically depicted in Figs. 12 and 13 , while Fig. 14 depicts the effect of personal COVID-19 protection on the dynamics of the control .

Fig. 3.

Simulations showing the number of susceptible humans .

Fig. 4.

Simulations showing individuals exposed to both malaria and COVID-19 .

Fig. 5.

Time series of individuals exposed to COVID-19 only .

Fig. 6.

Simulations showing individuals exposed to malaria only .

Fig. 7.

Simulations showing individuals infected with malaria only .

Fig. 8.

Simulations showing individuals infected with COVID-19 only .

Fig. 9.

Simulations showing individuals infected with both malaria and COVID-19 .

Fig. 10.

Simulations showing individuals infected with COVID-19 and exposed to malaria .

Fig. 11.

Simulations showing individuals infected with malaria and exposed to COVID-19 .

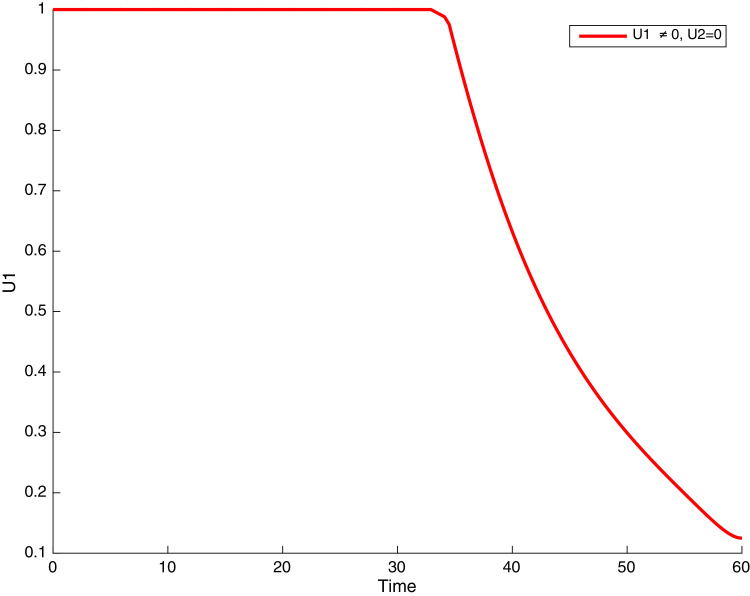

Fig. 12.

Simulations showing control .

Fig. 13.

Simulations showing control .

Fig. 14.

Simulations showing the effect of personal COVID-19 protection on the dynamics of the control .

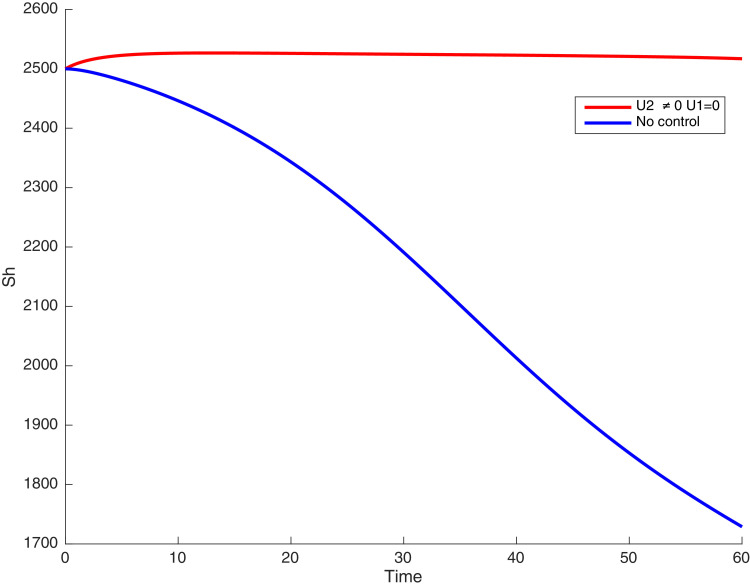

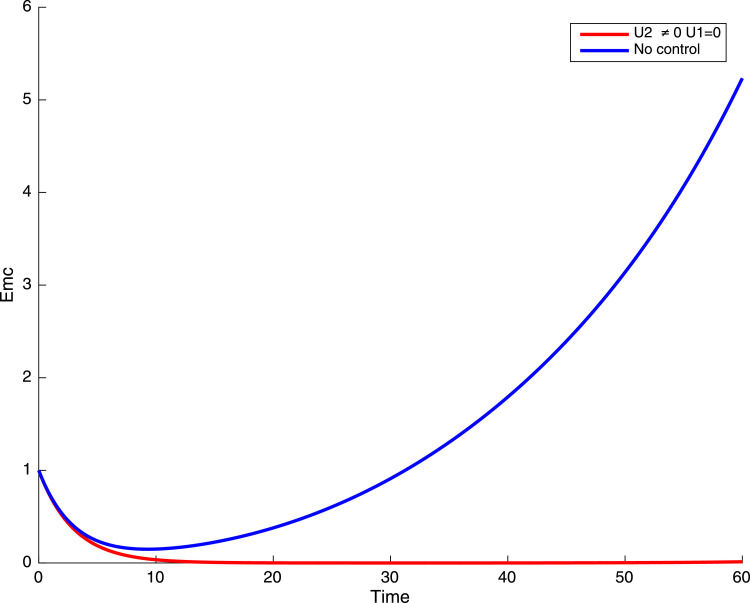

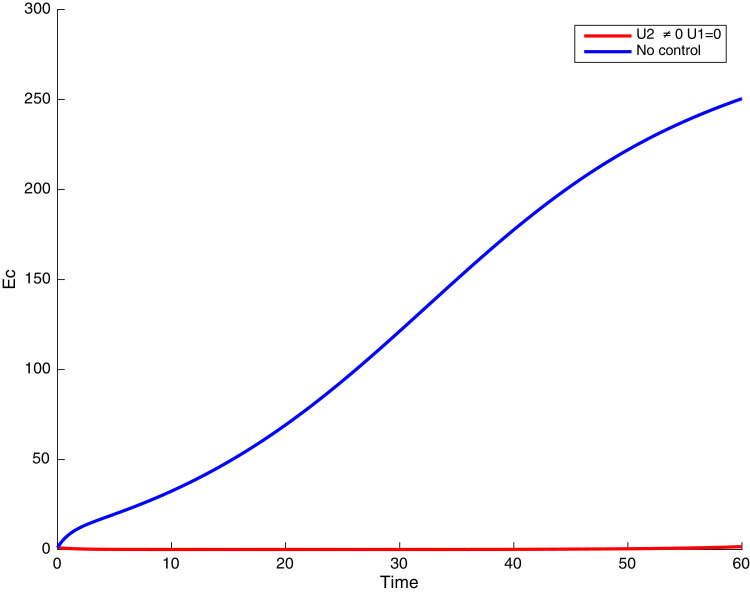

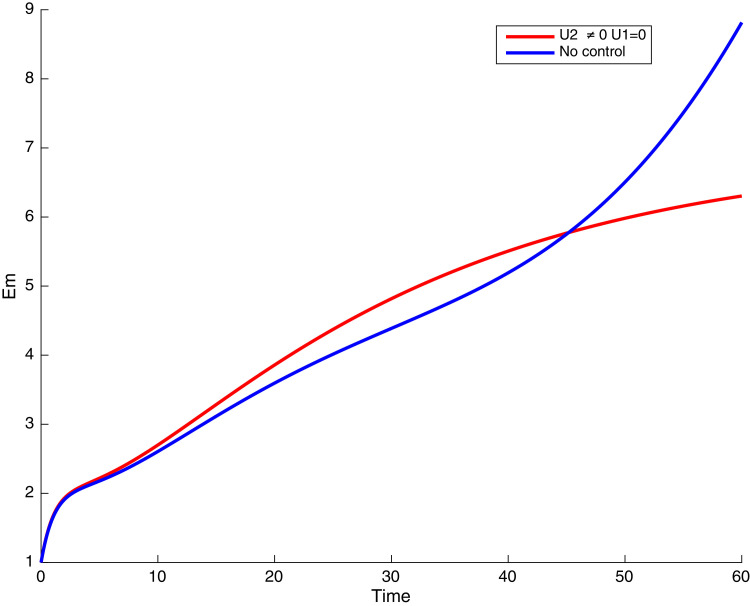

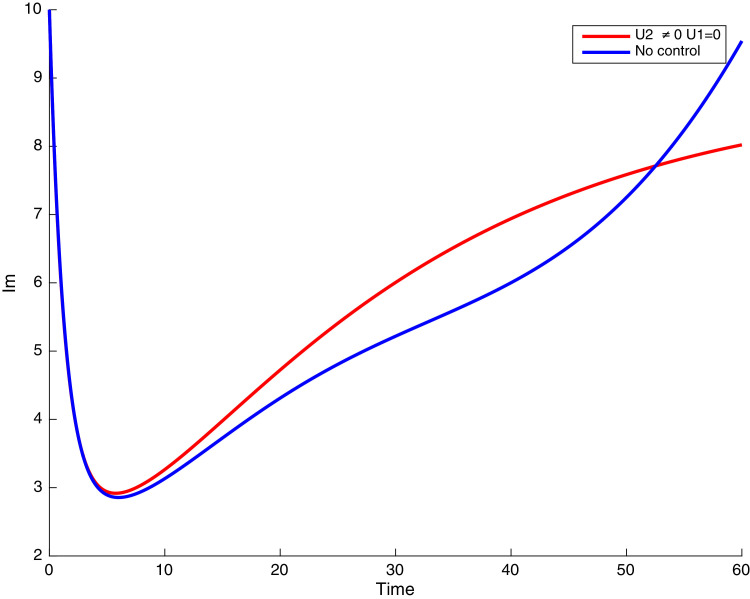

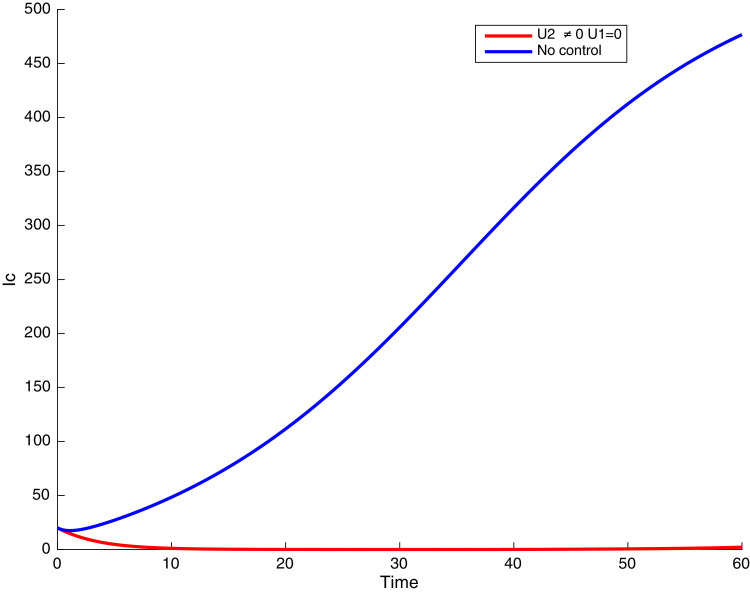

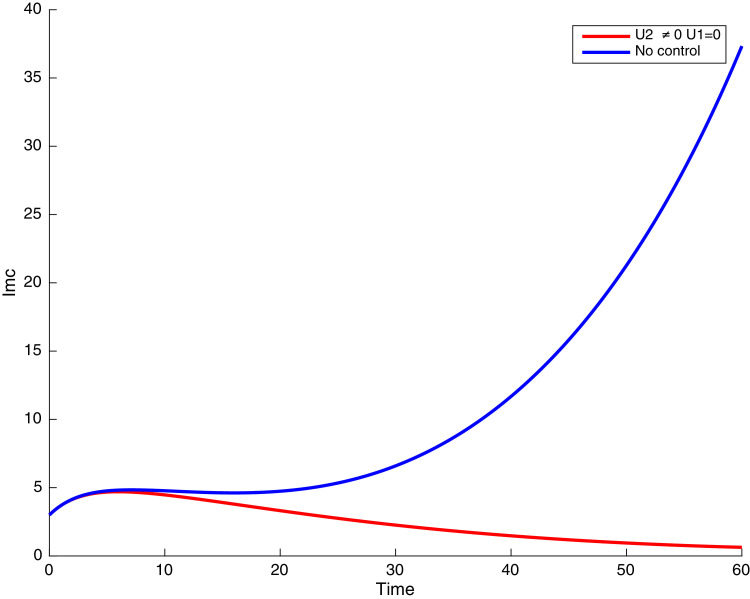

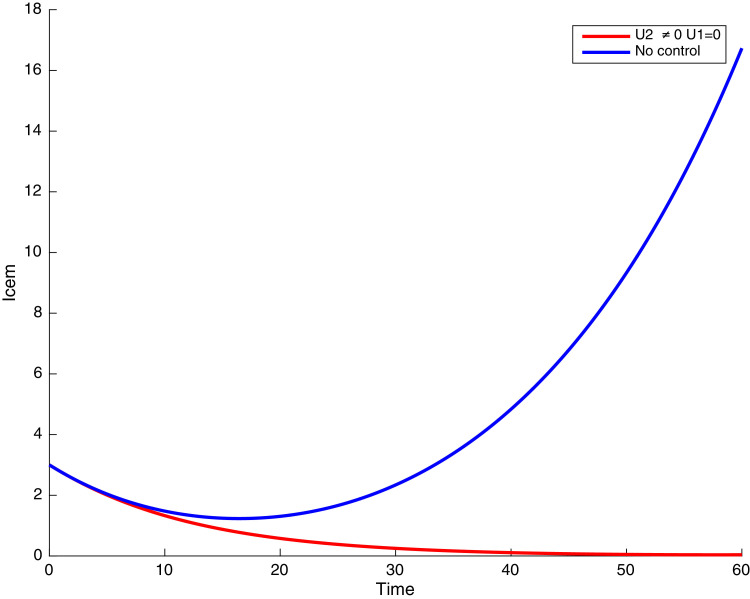

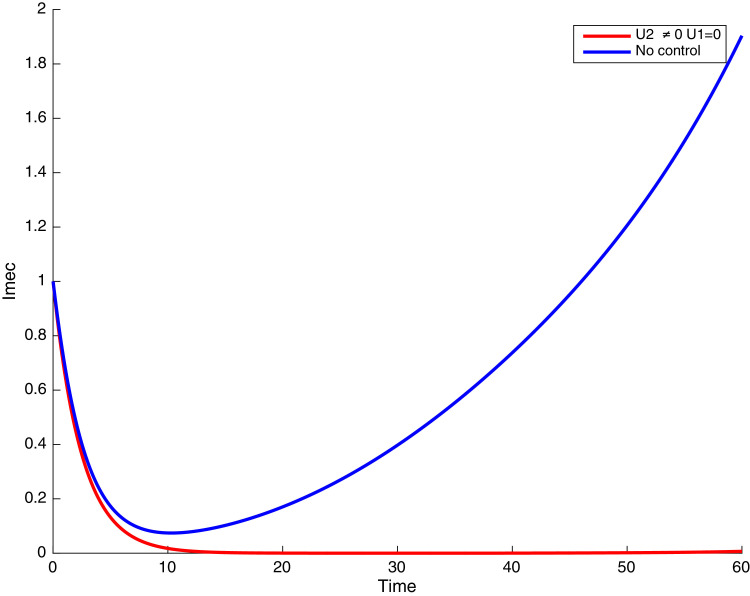

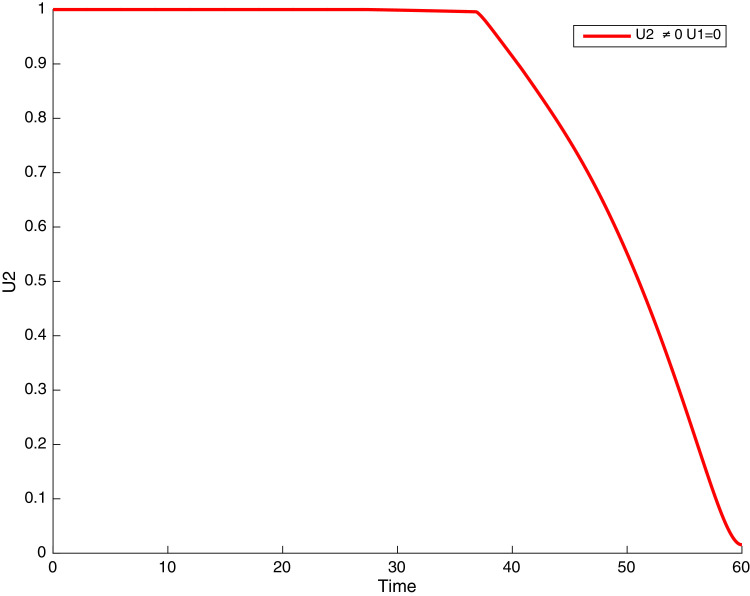

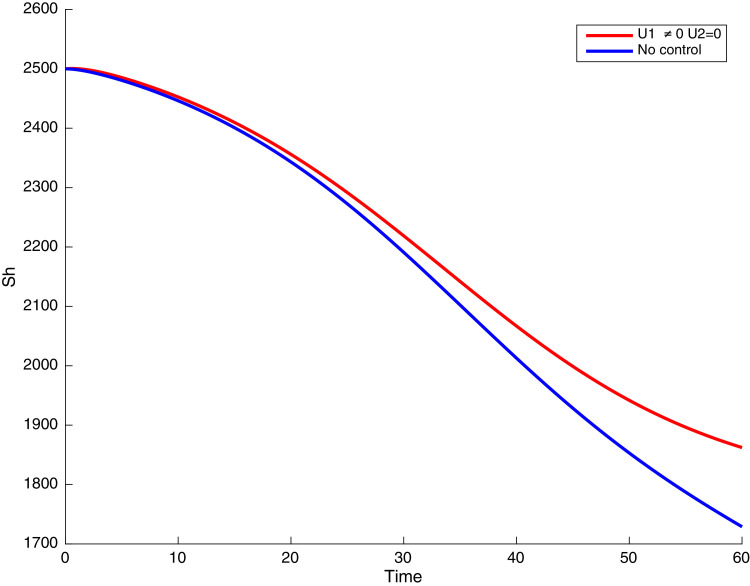

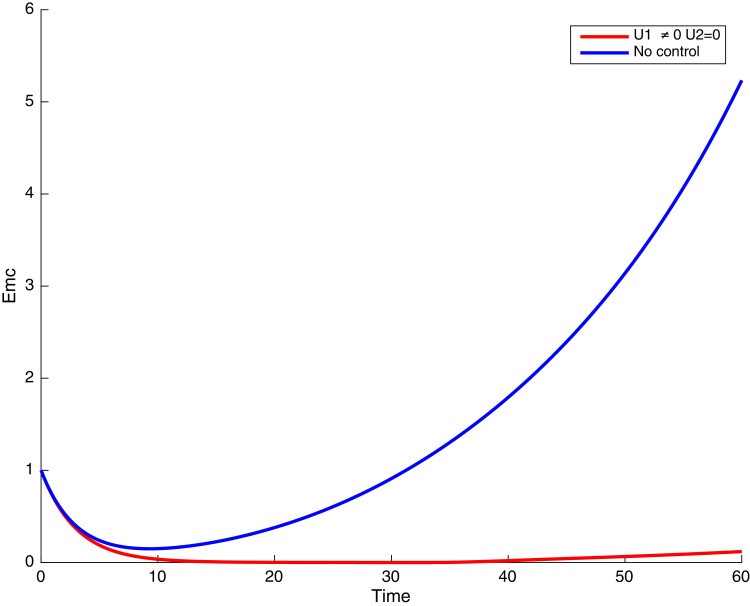

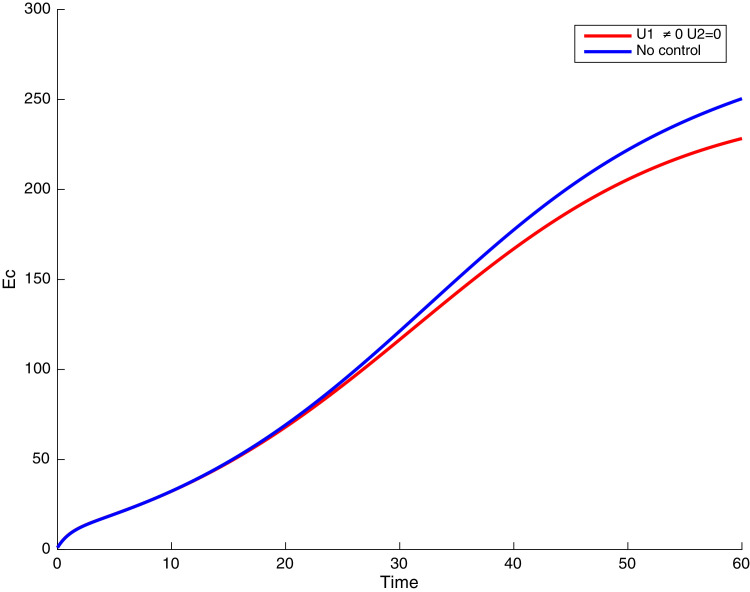

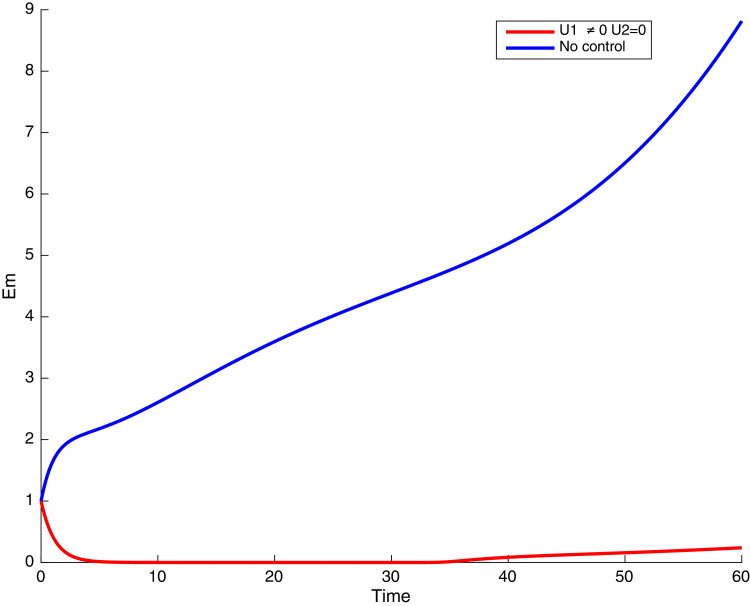

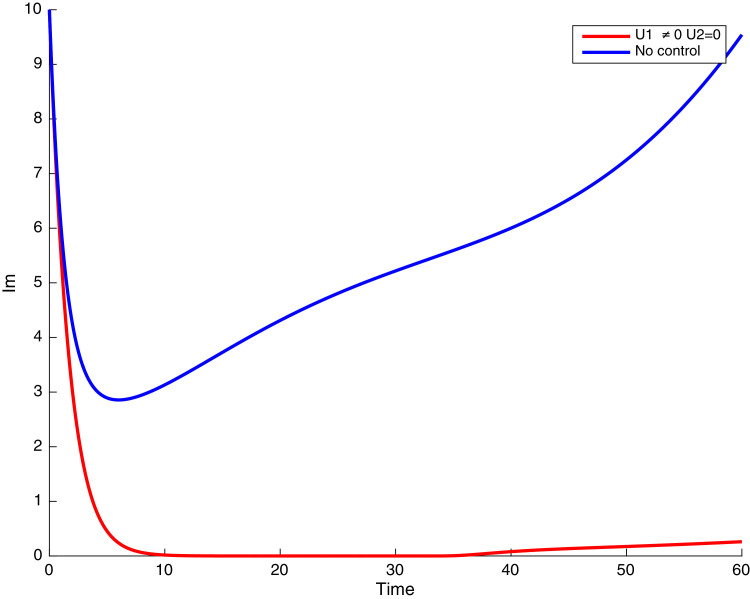

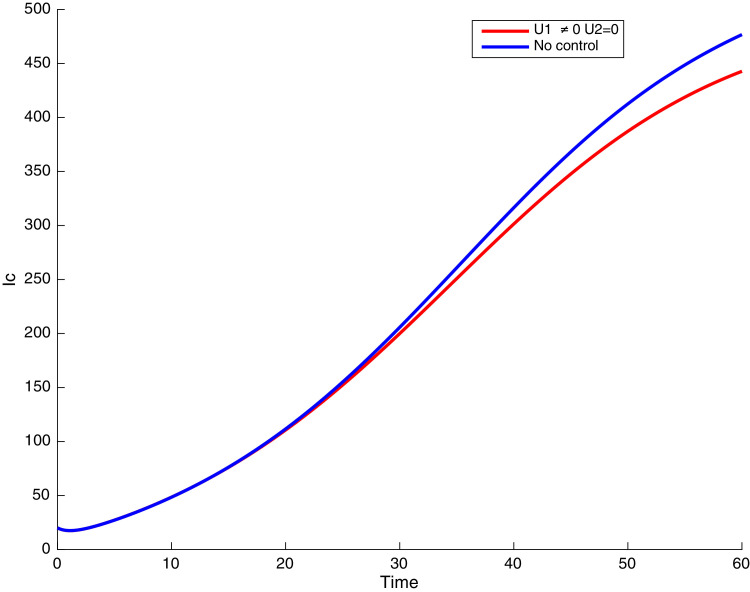

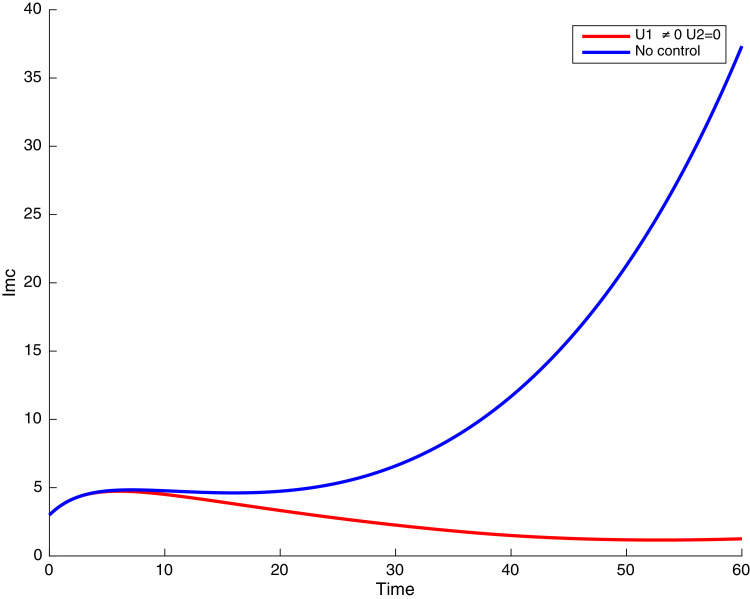

4.2. Simulations when there is no malaria prevention and prevention against COVID-19

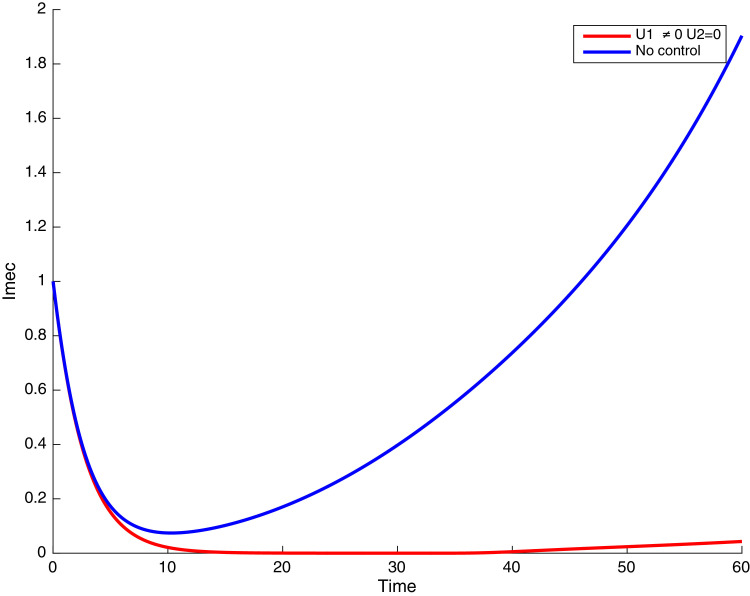

In this case, only the prevention against COVID-19 is implemented, i.e., control is used to minimize the objective function . In Fig. 15 , we observe that controls resulted in an increase in the number of susceptible humans while decrease is observed in the number of susceptible humans when no COVID-19 control measure is implemented in the community. From Fig. 16, Fig. 17, Fig. 18, Fig. 19, Fig. 20 , we also observe that when there is no malaria control, the COVID-19 control results in a decrease in the number of exposed and infectious to COVID-19 only, which is also the case on the Fig. 21, Fig. 22, Fig. 23 where there is a decrease in the number of exposed and infectious to both malaria and COVID-19 simultaneously. This is not the case in Figs. 18 and 19 where we can see that the effect of control on the infected with malaria is very temporary. This implies that prevention of COVID-19 would not have in a long run a positive effect on the fight against malaria. The control representing prevention against COVID-19 is graphically depicted in Fig. 24 .

Fig. 15.

Simulations showing susceptible when and .

Fig. 16.

Simulations showing malaria and COVID-19 exposed individuals when and .

Fig. 17.

Simulations showing COVID-19 exposed individuals when and .

Fig. 18.

Simulations showing malaria exposed individuals when and .

Fig. 19.

Simulations showing malaria infected individuals with when and .

Fig. 20.

Simulations showing COVID-19 infected individuals when and .

Fig. 21.

Simulations showing co-infected individuals when and .

Fig. 22.

Simulations showing COVID-19 infected individuals exposed to malaria when and .

Fig. 23.

Simulations showing malaria infected individuals exposed to COVID-19 when and .

Fig. 24.

Simulations showing COVID-19 control when and .

Additional graphical representations are provided in Appendix A, depicting the plausible situation at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when no prevention measures was in place (see Fig. 25, Fig. 26, Fig. 27, Fig. 28, Fig. 29, Fig. 30, Fig. 31, Fig. 32, Fig. 33, Fig. 34).

Fig. 25.

Simulations showing the number of susceptible susceptible when and .

Fig. 26.

Time series of malaria and COVID-19 exposed individuals when and .

Fig. 27.

Time series of COVID-19 exposed individuals when and .

Fig. 28.

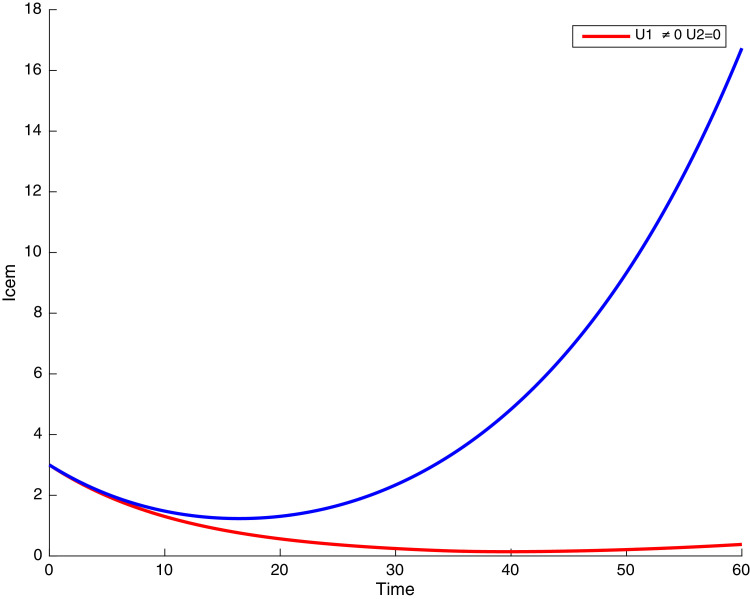

Time series of malaria exposed individuals when and .

Fig. 29.

Time series of malaria infectious indidividuals when and .

Fig. 30.

Time series of COVID-19 infectious individuals when and .

Fig. 31.

Time series of co-infected individuals when and .

Fig. 32.

Time series of COVID-19 infected individuals exposed to malaria when and .

Fig. 33.

Time series of malaria infected individuals exposed to COVID-19 when and .

Fig. 34.

Simulations of the control when and .

5. Conclusion

A deterministic compartmental model for the transmission dynamics of malaria and COVID-19 is proposed and analyzed. Theoretical results obtained are as follows. For the malaria-only and COVID-19 only models, it is shown that the DFE of each sub-model is locally asymptotically stable when their associated basic reproduction numbers and are less that unity, and unstable otherwise. Whenever and , the malaria-only and COVID-19 only sub-systems respectively have a locally asymptotically stable endemic equilibrium. However, by using the center manifold theory, under certain conditions when the bifurcation parameters and , the disease-free equilibrium of the COVID-19 only model 3.1 interchanges its stability with the endemic equilibrium as the threshold parameter and a forward or transcritical bifurcation occurs. This guarantees that the equilibria of the COVID-19 model system 3.1 are globally asymptotically stable.

Similarly, it is shown that when both bifurcation parameters and , the malaria-only model exhibits the phenomenon of backward or subcritical bifurcation [1], [3], [47], where a stable disease-free equilibrium co-exists with a stable endemic equilibrium, for a certain range of the associated reproduction number less than unity. Consequently, its equilibria are only locally stable. Consequently, under these conditions, the co-infection model (1) will undergo a backward bifurcation at , inherited from the the malaria-only model 3.2 [1], [3], [54], [55]. Thus, for the malaria and co-infection models, the classical requirement of having the associated reproduction number to be less than unity, although necessary, is not sufficient for disease elimination [1], [3]. In fact, the occurrence of a backward bifurcation further complicates malaria eradication efforts. The two diseases will co-exist whenever the reproduction number of each of the two diseases exceed unity (regardless of which number is larger).

Next, we incorporated time-dependent controls and into model system (1) and applied the Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle to determine the optimal prevention strategy for controlling the co-infection of COVID-19 and malaria. It is implicitly assumed that individuals adhere to the prevention measures for each disease. We analytically derived the optimality conditions for disease eradication.

Numerical simulations of the optimal control of the full model are carried out using a set of model parameter values mostly obtained from literature and others assumed within realistic range for the purpose of illustration to assess the impact of co-infection of the two diseases. Thus, the following are observed:

-

i)

The use of the two controls reduces the number of malaria and COVID-19 infected individuals as well as those co-infected with both diseases.

-

ii)

The exclusive use of COVID-19 prevention control measure reduces the number of COVID-19 infected individuals, and also the number of co-infected individuals, but does not prevent the increase of malaria infections.

-

iii)

The exclusive use of malaria prevention control aimed at reducing contact between humans and mosquitoes reduces the number of malaria infected individuals, and also slightly reduces the number of individuals infected with COVID-19 and co-infected individuals.

In summary, we formulated and analyzed a deterministic compartmental model for the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 and malaria and their co-infection in a given community. The COVID-19 only, malaria only and the co-infection models were qualitatively examined. By applying optimal control theory to the full model system (1), and using Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle, existence of the optimal control problem which satisfied the necessary conditions was established.

This study provides the first in-depth mathematical analysis of a comprehensive study for the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 and malaria. While efforts were made to incorporate several basic epidemiological features of the two diseases and their control using non therapeutic measures, the proposed study can be extended. Future studies could incorporate the following limitations

-

i)

therapeutic strategies for COVID-19 (treatment and vaccination and malaria (treatment and prophylactic drugs, vector-reduction strategies)

-

ii)

acquisition of malaria immunity for adults in malaria endemic settings, following repeated exposure [3]

-

iii)

treatment efficacy of both diseases. With the emergence of new COVID-19 strains, resistance to treatment should not be ignored [4].

-

iv)

cost and cost-effectiveness of the proposed control strategies [40], [42], [54], [56].

Appendix A. Simulations when malaria prevention and no prevention against COVID-19

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the world was struggling to understand what is happening and finding how to deal with the disease, there was basically no prevention measures against COVID-19. Fig. 25, Fig. 26, Fig. 27, Fig. 28, Fig. 29, Fig. 30, Fig. 31, Fig. 32, Fig. 33, Fig. 34 below depict this situation. In Fig. 25, we observe that malaria control could result in an increase in the number of susceptible individuals. From Figs. 28 and 29, we observe that the malaria prevention control lead to a decrease in the number of infected and infectious to malaria only. This is also the case in the Fig. 27, Fig. 30, Fig. 31, Fig. 32, and 33 where we observe that the control resulted in a decrease in the number of infected and infectious COVID-19 only and malaria and COVID-19 co-infection. That is, prevention of malaria only could potentially have a minimal positive effect on the fight against COVID-19. There is as expected an increase in the number of exposed and infectious individuals when there is no control being implemented in the community.

References

- 1.Mtisi E., Rwezaura H., Tchuenche J.M. A mathematical analysis of malaria and tuberculosis co-dynamics. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst. B. 2009;12(4):827–864. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CMA P., Tenreiro Machado J.A. Fractional model for malaria transmission under control strategies. Comput. Math. Appl. 2013;66(5):908–916. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukandavire Z., Gumel A.B., Garira W., Tchuenche J.M. Mathematical analysis of a model for HIV-malaria co-infection. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2009;6(2):333–362. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2009.6.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tchuenche J.M., Chiyaka C., Chan D., Matthews A., Mayer G. A mathematical model for antimalarial drug resistance. Math. Med. Biol. 2010:1–21. doi: 10.1093/imammb/dqq017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nadim Sk S., Chattopadhyay J. Occurrence of backward bifurcation and prediction of disease transmission with imperfect lockdown: a case study on COVID-19. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;140:110163. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu J.T., Leung K., Leung G.M. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):689–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng L.X., Jing S.L., Hu S.K., Wang D.F., Huo H.F. Modelling the effects of media coverage and quarantine on the COVID-19 infections in the UK. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2020:618–3636. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2020204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO, 2020, Malaria & COVID-19 https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/covid-19, Accessed November 30, 2020.

- 10.Ansumana R., Sankoh O., Zumla A. Effects of disruption from COVID-19 on antimalarial strategies. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1334–1336. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutman J.R., Lucchi N.W., Cantey P.T., Steinhardt L.C., Samuels A.M., Kamb M.L., Kapella B.K., McElroy P.D., Udhayakumar V., Lindblade K.A. Malaria and parasitic neglected tropical diseases: potential syndemics with COVID-19? Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020;103(2):572–577. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z., Magal P., Seydi O., Webb G.F. Understanding unreported cases in the COVID-19 epidemic outbreak in Wuhan, China, and the importance of major health interventions. MPDI Biol. 2020;9(50):1–12. doi: 10.3390/biology9030050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Z., Magal P., Seydi O., Webb G.F. Predicting the cumulative number of cases for COVID-19 in China from early data. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2020;17(4):3040–3051. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2020172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Z., Magal P., Seydi O., Webb G.F. A COVID-19 epidemic model with latency period. Infect. Disease Model. 2020;5:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kouakep Y.T., Tchoumi S.Y., DLM F., FGT K., Ngounou D., Mboula E., Kamla V., Kamgang J.C. Modelling the anti-COVID19 individual or collective containment strategies in cameroon. Appl. Math. Sci. 2021;15(2) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss D.J., Bertozzi-Villa A., Rumisha S.F., Amratia P., Arambepola R., Battle K.E., et al. Indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on malaria intervention coverage, morbidity, and mortality in africa: a geospatial modelling analysis. Lancet Inf. Dis. 2020;21:59–69. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30700-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherrard-Smith E., Hogan A.B., Hamlet A., et al. The potential public health consequences of COVID-19 on malaria in Africa. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1411–1416. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1025-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sumeyye C. Dynamic analysis of a mathematical model with health care capacity for COVID-19 pandemic. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;139:110033. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogerson S.J., Beeson J.G., Laman M., Poespoprodjo J.R., William T., Simpson J.A., Price R.N. ACREME investigators. Identifying and combating the impacts of COVID-19 on malaria. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):239. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01710-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogan A.B., Jewell B.L., Sherrard-Smith E., Vesga J.F., Watson O.J., Whittaker C., et al. Potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(9):e1132–e1141. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30288-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verduyn M., Allou N., Gazaille V., Andre M., Desroche T., M-C J., et al. Co-infection of dengue and COVID-19: a case report. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14(8):E0008476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernoulli D. Essai d’une nouvelle analyse de la mortalite causee par la petite verole et des avantages de l’inoculation pour la prevenir. Mem. Math. Phys. Acad. Sci. Paris. 1760:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dietz K., Heesterbeek J. Daniel Bernoulli’s epidemiological model revisited. Math. Biosci. 2002;180:1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(02)00122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedro S.A., Ndjomatchoua F.T., Jentsch P., Tchuenche J.M., Anand M., Bauch C.T. Conditions for a second wave of COVID-19 due to interactions between disease dynamics and social processes. Front. Phys. 2020;8:574514. [Google Scholar]

- 25.L. Pontryagin, V. Boltyanskii, R. Gamkrelidze, E. Mishchenko, The mathematical theory of optimal control process. 4, 1986,

- 26.Qiu Z. Dynamical behavior of a vector-host epidemic model with demographic structure. Comput. Math. Appl. 2008;56(12):3118–3129. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J., Ma Z. Global dynamics of an epidemic model with saturating contact rate. Math. Biosci. 2003;185:15–32. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(03)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perko L. Text in Applied Mathematics. Vol. 7. Springer; Berlin: 2000. Differential equations and dynamical systems. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korobeinikov A., Wake G.C. Lyapunov functions and global stability for SIR, SIRS, and epidemiological models. Appl. Math. Lett. 2002;15:955–960. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kermack W.O., McKendrick A.G. A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1927;115:700–721. [Google Scholar]

- 31.van den D.P., Watmough J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math. Biosci. 2002;180(1):29–48. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(02)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castillo-Chavez C., Song B. Dynamical models of tuberculosis and their applications. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2004;1(2):361–404. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2004.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiyaka C., Tchuenche J.M., Garira W., Dube S. A mathematical analysis of the effects of control strategies on the transmission dynamics of malaria. Appl. Math. Comput. 2008;195(2):641–662. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carr J. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1981. Applications Centre Manifold Theory. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hutson V., Schmitt K. Permanence and the dynamics of biological systems. Math. Biosci. 1992;111:1–71. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(92)90078-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dushoff J., Huang W., Castillo-Chavez C. Backwards bifurcations and catastrophe in simple models of fatal diseases. J. Math. Biol. 1998;36:227–248. doi: 10.1007/s002850050099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonyah E., Okoson K.O. Mathematical modeling of Zika virus. Asian Pacif. J. Trop. Dis. 2016;6(9):673–679. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mushayabasa S., AAE L., Modnak C., Wang J. Optimal control analysis applied to a two-path model for guinea worm disease. Electron. J. Differ. Equ. 2020;70:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joshi H.R., Lenhart S., Li M.Y., Wang L. Optimal control methods applied to disease models. Contemp. Math. 2006;410:187–207. [Google Scholar]

- 40.F. Saldana, J.A. Camacho-Gutierrez, A. Korobeinikov, Impact of a cost functional on the optimal control and the cost-effectiveness: control of a spreading infection as a case study, 2021, arXiv:2011.06648access February 1.

- 41.Fleming W., Rishel R. Vol. 1. Springer-Verlag; 1975. Deterministic and Stochastic Optimal Control; p. 222. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agusto F.B. Optimal isolation control strategies and cost-effectiveness analysis of a two-strain avian influenza model. Biosystems. 2013;113(3):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lukes D.L. Academic Press; New York, NY, USA: 1982. Differential Equation Classical to Controlled Mathematical in Science and Engineering. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirschner D., Lenhart S., Serbin S. Optimal control of the chemotherapy of HIV. J. Math. Biol. 1997;35:775–792. doi: 10.1007/s002850050076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams B.M., Banks H.T., Kwon H., Tran H.T. Dynamic multidrug therapies for HIV: Optimal and STI approaches. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2004;1(2):223–241. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2004.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lenhart S., Workman J.T. Mathematical and Computational Biology Series. Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2007. Optimal control applied to biological models. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okosun K.O., Makinde O.D. Optimal control analysis of malaria in the presence of non-linear incidence rate. Appl. Comput. Math. 2013;12(1):20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buonomo B. Analysis of a malaria model with mosquito host choice and bed-net control. Int. J. Biomath. 2015;8(6) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linton N.M., Kobayashi T., Yang Y., Hayashi K., Akhmetzhanov A.R., Jung S.-m., Yuan B., Kinoshita R., Nishiura H. Incubation period and other epidemiological characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infections with right truncation: a statistical analysis of publicly available case data. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9(2):538. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ngonghala C.N., Iboi E., Eikenberry S., Scotch M., MacIntyre C.R., Bonds M.H., Gumel A.B. Mathematical assessment of the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on curtailing the 2019 novel coronavirus. Math. Biosci. 2020;325 doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2020.108364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anguelov R., Dumont Y., Lubuma J., Mureithi E. Stability analysis and dynamics preserving nonstandard finite difference schemes for a malaria model. mathematical population studies. Int. J. Math. Demogr. 2013;20:101–122. [Google Scholar]

- 52.S. Zio, I. Tougri, B. Lamien, Propagation du COVID19 au burkina faso, modelisation bayesienne et quantification des incertitudes: premiere approche, preprint, Ecole Polytechnique de Ouagadougou (EPO) Ouagadougou (2020).

- 53.Chitnis N., Hyman J.M., Cushing J. Determining important parameters in the spread of malaria through the sensitivity analysis of a mathematical model. Bull. Math. Biol. 2008;70(5):1272–1296. doi: 10.1007/s11538-008-9299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Okosun O., Ouifki R., Nizar M. Optimal control analysis of a malaria disease transmission model that includes treatment and vaccination with waning immunity. Biosystems. 2011;106(2-3):136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tchoumi S.Y., Kamgang J.C., Tieudjo D., Sallet G. A basic general model of vector-borne diseases. Commun. Math. Biol. Neurosci. 2018;2018(3) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Agusto F.B., ELmojtaba I.M. Optimal control and cost-effective analysis of malaria/visceral leishmaniasis co-infection. PLoS One. 2017;12(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]