Abstract

Objective

To investigate the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the quality of life and social networks of older adults receiving community care services.

Methods

Quality of life and social network questionnaires were completed by older adults (n = 21) receiving home care services at three time points (2018, 2019, and during the first Australian COVID‐19 lockdown in 2020). Additional questions about technology use were included in 2020.

Results

Older adults’ quality of life significantly decreased during the pandemic compared to the prior year. During the pandemic, over 80% used technology to maintain contact with family and friends, and social networks did not change.

Conclusion

Government messages and support initiatives directed towards technology adoption among older adults receiving home care may assist with maintaining social connection during COVID‐19. Our findings add to the relatively limited understanding of the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the socio‐emotional well‐being of older people.

Keywords: covid‐19, lifestyle restrictions, lockdown, older adults, wellbeing

Policy Impact

This study provides evidence of immediate collateral consequences of the COVID‐19 outbreak, demonstrating an adverse impact on quality of life of older home care adults. The findings highlight the challenge of, but need for, health promotion efforts targeting well‐being. Better and targeted public health measures to improve and support supporting social and well‐being care needs for older adults during this crisis are required.

Practice Impact

Our findings can guide efforts to preserve and promote older adults’ mental health and well‐being during the COVID‐19 outbreak and crisis recovery period, and to inform strategies to mitigate potential harm during future pandemics.

1. INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization officially declared the novel coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) outbreak as a global pandemic on 11 March 2020, 1 and as of 14 October 2020, the total number of people diagnosed with COVID‐19 was 38,006,121 with 1,083,875 deaths in 188 countries/regions 2 ; among these, 27,323 cases and 904 deaths have been reported in Australia. 2

Current estimates suggest a 1‐2% case fatality rate, with concern about higher transmission of the virus to older people and those with underlying medical conditions. 3 Consequently, the COVID‐19 virus outbreak has profoundly altered the daily life of older adults, with specific recommendations and restrictions varying within and between countries. Similar to many countries, Australia imposed rapid restrictions of physical distancing, border restrictions, recommendations to stay at home, avoid contact with others and avoid non‐essential travel between 22 March and 1 May 2020 to mitigate the spread and impact. 4 However, long‐term effects of prolonged physical distancing will likely affect older adults, who are particularly vulnerable to social isolation. 5

The direct and indirect psychological and social effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic are pervasive and could affect individual well‐being now and in the future. 3 Studies that have tracked the long‐term sequelae of previous coronavirus pandemics (eg 2002 severe acute respiratory syndrome) suggest that psychological difficulties, including depression, anxiety and impaired quality of life, can persist for years post‐outbreak. 6 Evidence further suggests that measures to mitigate virus spread can exacerbate lasting psychological distress, including elevated levels of depression. 7

From a public health perspective, it is crucial to identify protective factors that sustain older adults’ quality of life during the pandemic. Whilst some research has started to examine the impact of COVID‐19 on quality of life, this has been limited to students 8 and the general population aged younger than 75 years. 9 One cohort that has received little attention are older adults in receipt of home‐based aged care services. People receiving home care services are generally older, more socially isolated, have multiple chronic conditions and require assistance 10 with everyday living activities through both informal care and formal care compared to older adults not receiving home care. 11 This study therefore aimed to investigate the immediate impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic lockdowns on quality of life, anxiety, depression and social networks among older adults who were receiving home care services in Australia.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design, setting and participants

A longitudinal study covering three data collection periods (September 2018, March 2019, May 2020) was undertaken. This study was approved by the Macquarie University Ethics Committee (ref 52 020 671 215 911).

2.2. Participants

Individuals (n = 71) receiving home and community‐based services from New South Wales, Australia, were invited to participate in the study. The sample was drawn from a prospective longitudinal cohort study of older adults receiving home care. 12 All participants were receiving in‐home care, aged ≥ 65 years and had no self‐reported dementia diagnosis. Participants were established users of home care services in 2018, which included services such as attendance at day‐care centres, social support or in‐home nursing. This sample had already completed quality of life and social network measures in September 2018 and April 2019. 12

Of the total 71 people invited to participate in the 2020 assessments, 21 participated (30% response rate). Respondents who did and did not complete the surveys were similar in terms of age, previous quality of life and social networks, but a greater proportion of individuals living alone completed the surveys (67% vs 51%, F = 9.6, P = .003; Table S1).

2.3. Measures

A physical copy of the questionnaire was distributed in May 2020 (a period when government‐mandated restrictions had started to ease, including outdoor gatherings permitted for ten people instead of two, and reopening of small cafes and restaurants rather than only essential services) and asked respondents to reflect back to April 2020 during the lockdowns. The questionnaire had 61 questions on: (i) demographics; (ii) social networks (Lubben Social Network Scale, LSNS‐6) 13 ; (iii) quality of life (EQ‐5D‐5L) 14 which contains questions for mobility, self‐care, pain/discomfort, usual activities and anxiety/depression subdomains, and five possible response options—no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, extreme problems/unable to; and (iv) technology use and adoption (use of new technology, technology type and frequency of use) (see Supplementary Material).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using STATA 15 (Stata Corp). Descriptive statistics were used to summarise assessments. Fisher's exact analysis was used to assess differences in distribution of responses for the five EQ‐5D‐5L subdomains across the three years. For the EQ‐5D‐5L, an index value was calculated using English national data as a reference. 15 Multilevel mixed linear regression using a Bonferroni alpha correction was used to look at EQ‐5D‐5L index and social network scores over time, controlling for age and gender. Pearson correlations were used to determine associations with quality of life and social networks.

3. RESULTS

The mean age of respondents was 82.1 (SD 5.6) years (range 79‐90 years), and 76.2% were female. Full demographic and service use characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and characteristics of 21 older adults

| Characteristics | n (%) | Characteristics | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Wearable | 1 (4.8) | ||

| Female | 5 (76.2) | Smart home device | 2 (9.5) | |

| Male | 16 (23.8) | Frequency of phone use for keeping contact during lockdown | ||

| Age | A few times a day | 6 (28.6) | ||

| Mean [SD] | 82.1 [5.6] | Once a day | 2 (9.5) | |

| 65‐74 | 3 (14.3) | A few times a week | 3 (14.3) | |

| 75‐84 | 10 (47.6) | Once a week | 1 (4.8) | |

| 85+ | 8 (38.1) | <Once a month | 5 (23.8) | |

| Relationship status | N/A | 3 (14.3) | ||

| Widowed | 11 (52.4) | Missing | 1 (4.8) | |

| Divorced | 4 (19.0) | Having the necessary knowledge to use this technology | ||

| Never married | 3 (19.0) | Strongly disagree | 1 (5) | |

| Married | 2 (9.5) | Disagree | 3 (15) | |

| Country of birth | Agree | 13 (65) | ||

| Australia | 14 (66.7) | Strongly Agree | 2 (10) | |

| UK | 3 (14.3) | Don't know | 1 (5) | |

| Iran | 1 (4.8) | Importance of technology for keeping contact during lock down | Family | Friends |

| Iraq | 1 (4.8) | Very important | 12 (57.1) | 9 (42.9) |

| Egypt | 1 (4.8) | Important | 2 (9.5) | 3 (14.3) |

| Germany | 1 (4.8) | Neutral | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) |

| Years of Education | Less important | 0 (0) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Primary | 2 (9.5) | Not at all important | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) |

| Secondary | 5 (23.8) | Likelihood of continued phone use for contact | Family | Friends |

| Trade | 3 (14.3) | Not at all likely | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.8) |

| High school certificate | 2 (9.5) | Not really | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) |

| Diploma | 3 (14.3) | Somewhat likely | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) |

| Bachelor's degree | 3 (14.3) | Very likely | 14 (66.7) | 14 (66.7) |

| Postgraduate degree | 3 (14.3) | N/A | 1 (4.8) | 3 (14.3) |

| Employment status | Type of aged care service received | |||

| Retired | 20 (95.2) | Domestic assistance | 13 (61.9) | |

| Semi‐retired | 1 (4.8) | Home maintenance | 3 (14.3) | |

| Pension | Home modification | 2 (9.5) | ||

| Seniors, disability, widow | 18 (85.7) | Full‐time home duties | 0 (0) | |

| No pension | 3 (14.3) | Goods assistive technology | 1 (4.8) | |

| Technology use | Meals and other food services | 3 (14.3) | ||

| New technology use a | 3 (14.3) | Personal care | 1 (4.8) | |

| Type—Tablet | 2 (66.6) | Nursing | 1 (4.8) | |

| Type—Computer | 1 (33.3) | Allied health | 9 (42.9) | |

| Existing technology use | Specialised support | 0 (0) | ||

| Telephone | 18 (85.7) | Respite care | 1 (4.8) | |

| Mobile | 13 (61.9) | Transport | 2 (9.5) | |

| Tablet | 7 (33.3) | Social support | 3 (14.3) | |

| Computer/laptop | 11 (52.4) | Other | 5 (23.8) | |

Respondents answered yes for this category.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

During the lockdown, 90.5% of respondents used technology to keep in contact with family or friends. A small number of respondents (14.3%) adopted new technology, mostly for video‐communication (eg Zoom) using a tablet (66.6%) or laptop (33.3%). Of the respondents who used technology, more than half rated the importance of technology for keeping in contact with family (66.6%) and friends (57.2%) as important to very important (Table 1).

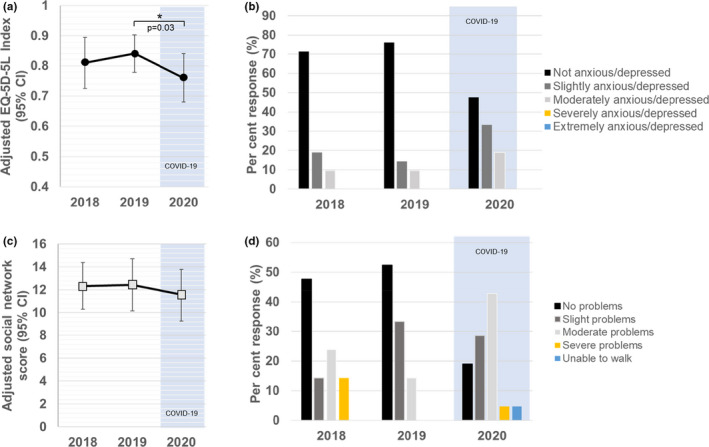

For the EQ‐5D‐5L, the subdomain scores are detailed in Figure 1A and Table S2. The mean and standard deviation for the index scores were 0.79 (±0.20) in 2018, 0.82 (±0.14) in 2019 and 0.74 (±0.19) in 2020. The adjusted estimated marginal mean differences for the EQ‐5D‐5L index score were not significantly different between 2018 and 2019 (Adj Diff: 0.03; 95%CI:‐0.04‐0.11; P = 1.00) and between 2018 and 2020 (Adj Diff:‐0.05; 95%CI:‐0.14‐0.04; P = .58); however, there was a decrease in the EQ‐5D‐5L index score in 2020 from 2019 (Adj Diff:‐0.08; 95%CI:−0.16 to −0.01; P = .03) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Adjusted estimated marginal mean EQ‐5D‐5L index score (A) and total social network score (B) at three time points (error bars represent 95% CI). A detailed breakdown of responses to two quality of life domains, anxiety and depression (C) and mobility (D), is shown for three time points

For the LSNS‐6, the mean and standard deviation were 12.86 (±6.10) in 2018, 13.05 (±4.90) in 2019 and 12.09 (±6.16) in 2020, with cut‐off point of < 12 described for an individual to be at risk for social isolation. The adjusted estimated marginal mean difference for the social network total score did not differ significantly across the three years, 2018 to 2019 (Adj Diff: 0.10; 95%CI: −2.25‐2.45; P = 1.00) and between 2018 and 2020 (Adj Diff: ‐0.76; 95%CI: −3.16‐1.63; P = .10) and 2020 from 2019 (Adj Diff: −0.86; 95%CI: −0.3.88‐2.16; P = 1.00) (Figure 1B). There were no significant correlations between EQ‐5D‐5L total or domain scores and social networks for each year (all P's > 0.05).

4. DISCUSSION

This study assessed any immediate changes in quality of life and social networks of older home care recipients in Australia associated with the first COVID‐19 lockdown. We found that older adults reported lower quality of life compared with the previous year, although quality of life did not differ from two years prior. Interestingly, participants’ social networks with family and friends did not change during lockdowns, with telephone contact most often used to keep in contact with family and friends.

There are emerging calls bringing attention to the likely impact of the global pandemic on the mental health of older adults. 16 Older adults rated technology as being important to keep in contact, and this was particularly relevant for keeping in touch with family. However, only a small number of respondents commenced a new form of technology to make contact with family and friends with over 70% of older adults reporting having the necessary knowledge to use existing technology. We were unable to find associations with reduced quality of life and social networks. This suggests that other factors, such as other physical, mental or cognitive conditions and co‐morbidities, may have impacted older adults’ quality of life. 17 Furthermore, our results suggest that factors contributing to lower quality of life are mixed, with domains mobility and anxiety or depression being worse, but better with self‐care in 2020. This supports studies that find a significant association between severity of depression and poorer quality of life in older persons. 18 , 19

4.1. Strengths, limitations and future directions

A strength of this study is its longitudinal design which enables comparison of changes in health and social outcomes pre‐ versus post‐COVID‐19 in older home care recipients. However, our study is limited by its small sample size and may not represent the geographic, cultural and socio‐economic make up of Australia. Given Australia has had a relative low morbidity and mortality rate, results may also not be generalise internationally. We also had a low response rate, with the survey administered after lockdowns, allowing for potential bias (eg retrospective recall) in the sample, and therefore, the impact of COVID‐19 cannot be fully explored (see Supplementary Material). Future national studies should evaluate the longer‐term consequences of the COVID‐19 outbreak and recovery on older adults’ quality of life.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This study provides initial results about the consequences of the COVID‐19 outbreak, demonstrating a small reduction in quality of life for older adults receiving home care services compared to the year prior to the pandemic. The findings highlight the need for larger‐scale investigations of the impacts of COVID on vulnerable older peoples.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest declared.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Siette J, Dodds L, Seaman K, et al. The impact of COVID‐19 on the quality of life of older adults receiving community‐based aged care. Australas J Ageing. 2021;40:84–89. 10.1111/ajag.12924

Funding information

None.

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO . Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019‐nCoV). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2020. https://www.who.int/news‐room/detail/30‐01‐2020‐statement‐on‐the‐second‐meeting‐of‐the‐international‐health‐regulations‐(2005)‐emergency‐committee‐regarding‐the‐outbreak‐of‐novel‐coronavirus‐(2019‐ncov) Accessed October 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. John Hopkins University .Coronavirus Resource Centre. 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/ Accessed October 14, 2020.

- 3. Dawes P, Siette J, Earl J, et al. Challenges of the COVID‐19 pandemic for social gerontology in Australia. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 39(4):383‐385. 10.1111/ajag.12845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Department of Health . Update on coronavirus (COVID‐19) measures from the Prime Minister. 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/news/update‐on‐coronavirus‐covid‐19‐measures‐from‐the‐prime‐minister. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- 5. Siette J, Wuthrich V, Low L‐F. Social preparedness in response to spatial distancing measures for aged care during COVID‐19. J Am Med Direct Assoc. 2020;21(7):985‐986. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee AM, Wong JGWS, McAlonan GM, et al. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;52(4):233‐240. 10.1177/070674370705200405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet (British edition). 2020;395(10227):912‐920. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khan AH, Sultana MS, Hossain S, et al. The impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health & wellbeing among home‐quarantined Bangladeshi students: A cross‐sectional pilot study. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:121‐128. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dawson DL, Golijani‐Moghaddam N. COVID‐19: Psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2020;17:126‐134. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. AIHW . Chapter 6.3 Older Australians and the use of aged care. Australia's Welfare 2015: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brett L, Nguyen AD, Siette J, et al. The co‐design of timely and meaningful information needed to enhance social participation in community aged care services: Think tank proceedings. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2020;39(1):e162‐e167. 10.1111/ajag.12706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Siette J, Georgiou A, Westbrook J. Observational cohort study investigating cognitive outcomes, social networks and well‐being in older adults: a study protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e029495. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, et al. Performance of an abbreviated version of the lubben social network scale among three european community‐dwelling older adult populations. The Gerontologist. 2006;46(4):503‐513. 10.1093/geront/46.4.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. EuroQol Group . EuroQol ‐ a new facility for the measurement of health‐related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199‐208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dolan P. Modelling valuations for health states: the effect of duration. Health Policy. 1996;38(3):189‐203. 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00853-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID‐19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547‐560. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Divo MJ, Martinez CH, Mannino DM. Ageing and the epidemiology of multimorbidity. The European Respiratory J. 2014;44(4):1055‐1068. 10.1183/09031936.00059814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sivertsen H, Bjørkløf GH, Engedal K, et al. Depression and quality of life in older persons: a review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2015;40(5–6):311‐339. 10.1159/000437299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chang YC, Ouyang WC, Lu MC, et al. Levels of depressive symptoms may modify the relationship between the WHOQOL‐BREF and its determining factors in community‐dwelling older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(4):591‐601. 10.1017/s1041610215002276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material