Abstract

Objective

Healthcare workers in Pacific Island Countries face unique workload and infection control hazards because of limited resources, cultural practices and local disease burden. In the context of COVID‐19, concern around healthcare worker safety escalated in the region, triggering the need for a relevant resource.

Methods

We describe a collaborative, participatory action‐research approach with a diverse range of local clinicians in Pacific Island Countries to design, develop and implement a practical guideline assisting clinicians to work safely during the pandemic.

Results

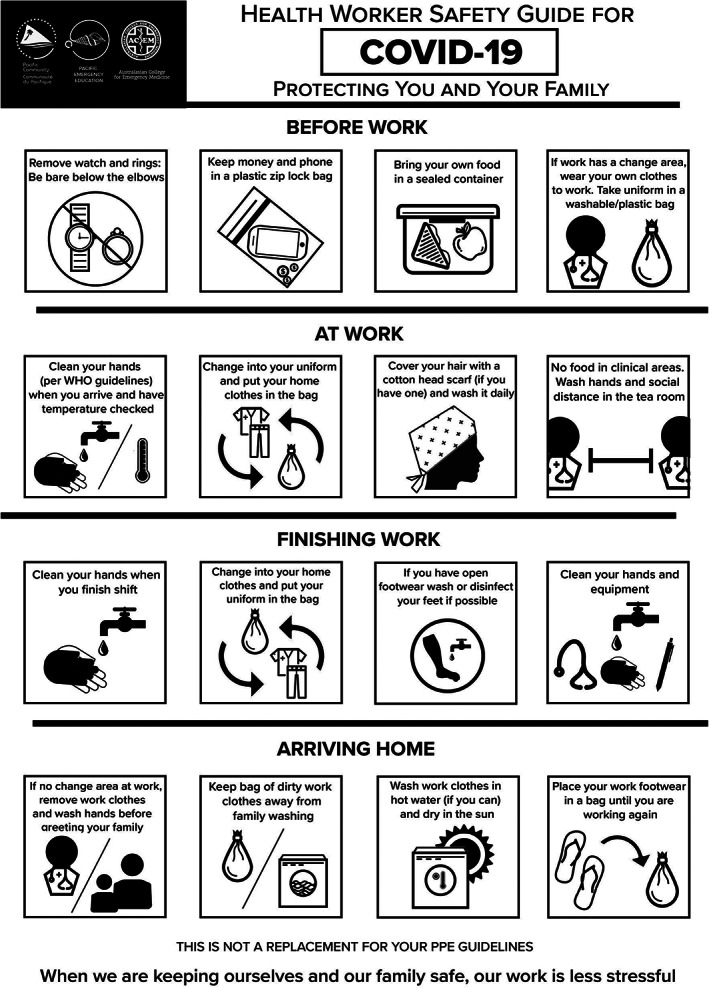

The resulting Health Worker Safety Guide for COVID‐19 is a relevant and usable protocol developed using local knowledge and now available in several Pacific languages.

Conclusion

We recommend a creative approach to facilitate meaningful communication with this group of clinicians, including low resolution technology and use of social media platforms.

Keywords: COVID‐19, emergency care, guideline, infection control, Pacific Island, public health

Key findings.

PIC clinicians require context‐appropriate, practical guidelines for COVID‐19 safety that recongnise their unique strengths and challenges.

A collaborative, participatory action‐research approach using low technology and multiple communication modes will maximise engagement and outcome relevance for Pacific stakeholders.

The Health Worker Safety Guide has high utility, is supported by regional partners and has been translated into multiple regional languages.

Background

As the COVID‐19 crisis evolved around the world, the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM) established an ongoing programme of support forums specific to managing COVID‐19 in the region. These events were held by the Global Emergency Care Committee (GECCo) as part of ACEM's wider commitment to the development of Emergency Care (EC) across the Pacific. 1

Initial forums established that no regional protocol existed to mitigate the risk of virus transmission to the families of healthcare workers (HCW) moving between home and the workplace. The possibility of inadvertently spreading COVID to family members creates enormous stress for HCW everywhere, but with often crowded living spaces and a strong extended family culture keeping vulnerable older relatives at home, this is particularly worrying for Pacific Island Country (PIC) HCW.

Forum participants agreed that the tools assisting HCW in Australia and New Zealand were inappropriate for the low resource settings, which characterise EC in the Pacific. 2 The Pacific Emergency Education (PEE) team agreed to lead a project to design a regionally applicable guideline providing a practical approach to clinical safety.

The PEE team is a collaboration between two clinical nurse specialists in emergency who have developed and delivered Pacific nursing education programmes and an Australian paramedic with an interest in health technology. The PEE website has been developed for sharing resources that are relevant and accessible for PIC clinicians. The direction of the team is informed by the Pacific Research Principles of ‘respect for relationships, respect for knowledge holders, reciprocity, holism and using research to do good’. 3

Development of the guideline

Development of a Pacific‐centred tool required a process that was collaborative, iterative and partnership based. An initial draft design was developed around core concepts reflecting regional considerations. These included easy replication in black and white, use of pictographs to convey information across linguistically diverse settings and an understanding of the environmental conditions underpinning clinical practice in the Pacific. This process was a practical endeavour informed by previous experience and relationships working alongside Pacific HCW. 4

Support and constructive feedback from the group of expert clinicians participating in the GECCo forums informed the first draft, which was then taken to the wider community of Pacific clinicians. The draft poster and a list of questions were widely circulated and profiled on the PEE website, inviting responses over a 4‐week period in May 2020. Questions were formulated to allow commentary on the tool itself and to facilitate discussion and feedback on key issues and areas of vulnerability.

What are you doing already to stay safe at work?

What are your thoughts on the COVID poster?

What access do you have to hand washing and changing facilities?

How are you managing food sharing in your area?

What other ideas do you have for managing COVID patients in your area?

Challenges in the design and circulation processes included human, geographical and technological constraints – all of which required specific, locally appropriate responses.

Snowball recruitment utilised the valuable interpersonal relationships that are central to communication in the Pacific. Reaching out to healthcare workers via multiple platforms including informal social media sites facilitated participation from clinicians who may have felt uncomfortable using a formal feedback process.

The size of the region and distance between populations makes it difficult to target large groups at one time. Many clinicians work in isolated environments or small facilities. Identified champions shared the resource via their own local networks and provided aggregated feedback allowing HCW without direct internet access to take part in the process.

Developing a simple, vector‐based black and white poster document with a low file size was important for accessibility in regions with low telecommunication infrastructure. Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator applications were used to develop and design the poster. The file was finalised at 3.8 MBs and able to be compressed to below 700 KB without marked quality loss. The Pacific has a prevalence of mobile based internet connectivity (as opposed to fixed line internet access) and thus accessibility benchmarks were based on third generation mobile network (3G) download speeds. The webpage storing the document was designed to have limited data strain on slower internet systems, and the page able to be viewed in under 10 s on a mimicked slow 3G network by limiting network throttle speeds to 376 kb/s using Google Developer tools. The page was also tested on older 2G network speeds without substantial time being required for content to become accessible to the user. 5

The submission button was designed to automatically reset, facilitating use in shared workspaces where a single low bandwidth connection is accessed by multiple computers. The design made use of a simple large coloured submission button to guide users unfamiliar with an interactive format.

A Participatory Action Research (PAR) method was utilised, providing the structure for a social, practical and collaborative process built on relationships with stakeholders. Benefits of PAR include community generation of knowledge and the continuous cycle of quality improvement. 6 The grounding of PAR in respect for community knowledge empowers participants in decision making that affects them. Focus on engagement with PIC clinicians and recognition of their lived experiences not only adheres to the Pacific Research Principles but also ensures that the tools created are relevant and accessible. A logframe matrix is used to present a summary of the process in a structured format (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Logframe of processes

| Inputs |

|

| Activities |

|

| Outputs |

|

| Outcome |

|

| Anticipated impact |

|

Outcomes

We received 37 submissions; however, this number does not take into account the aggregated feedback shared by clinical champions after local consultation with groups of colleagues, so the actual number of individuals involved is much higher than this. PIC responses came from Tuvalu, Vanuatu, Fiji, Kiribati and Federated States of Micronesia. Non‐PIC responses came from Nepal and both Pasifika and Pacific affiliated clinicians in Australia and New Zealand.

The breakdown of HCW roles was:

Nursing = 24 (aggregate responses were all collected by champions in this cohort)

Medical = 10

Public health = 1

Unidentified = 2

Thematically grouped responses identified areas of concern about access to laundering and handwashing facilities, issues around safe food sharing and the lack of designated eating areas. Local clinicians also identified and shared solutions that they were implementing in response to the threat of COVID‐19. The full range of responses can be seen at https://www.pacificemergencyeducation.org/corona‐policy‐development. Table 2 illustrates a selection of participant responses grouped by question type.

TABLE 2.

Selected responses from PIC clinicians

| What are you doing already to stay safe at work? |

| ‘Being in the frontline means keeping myself safe from this COVID‐19 so I can serve others without being infected’ |

| ‘Concern re aerosol spread has led to increased spacer use and removal of nebuliser station’ |

| What are your thoughts on the COVID‐19 poster? |

| ‘I just finished sending the poster to other nurses so they can have a look and thanks for the invitation. Looking at this chart you've sent, it's easy to follow and instructions are clearly stated’ |

| ‘I think this poster is everything we need in our hospital. It's really nice. Thank you very much. I will pass it on to other nurses for comment’ |

| What access do you have to handwashing and changing facilities? |

| ‘There is no proper changing place or area for us nurses to change, no proper place for us to have tea, while most times we used the same station where we worked as a tea area, so safety will be hard’ |

| ‘No access to proper change rooms (in our ED) but there is a shared change area with outpatients that could be better used’ |

| How are you managing food sharing in your area? |

| ‘Food sharing plays a crucial role in team bonding and stress reduction. It should be only in the tea room and not in a big group’ |

| ‘In our custom, sharing of food is common for everyone so having a notice like this will be a good reminder’ |

| ‘(Our country) is where people are not used to eating by themselves in front of others without sharing, including using same utensils or sharing fruit. We need to adopt a “hygienic” method of sharing’ |

| What other ideas do you have for managing COVID patients in your area? |

| ‘I am not sure of other Pacific island health facilities if staff locker is available but we do not have those and seeing the importance of it as part of infection prevention and control. Staff can keep their items e.g. pens in it rather than to bring them back to their homes’ |

| ‘Due to lack of hot water, we are emphasising use of detergent and drying in the sun’ |

| ‘I have one suggestion, for the management to get a washing machine purposely for staff scrubs, so that we minimise transmission to our families. What is used in the hospital stays in the hospital’ |

| ‘Only one attendant is allowed to stay with the patient. Chairs have been placed outside for family attendants to sit on. We advised parents not to bring in their kids in the hospital if they are not sick. We advised sick elderly that need refill of meds to get refill for at least 3 months, so they will not be coming every month just for refill. Well unless if they are very sick and need medical attention’ |

The final Health Worker Safety Guide for COVID‐19 poster is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Health Worker Safety Guide poster.

Lessons learnt

The challenges of engaging nurses in research and policy decisions are not limited to the Pacific. Participation in research and policy is affected here as elsewhere by a lack of professional confidence and the hierarchical nature of health systems. 7 However, the remote and widely scattered nature of the Pacific communities amplifies the difficulty of gathering frontline feedback. A combination of limited regional connectivity and widespread resource constraint means access to computers and/or the internet is often restricted. 8 This particularly affects remote clinic nurses who carry the highest community responsibility and impacts female nursing staff who often share telephone, internet and social media accounts with their husbands.

The Pacific Research Principles formed the basis for a range of strategies designed to reduce barriers to participation and encourage PIC HCW to share their experiences in core areas critical to possible transmission between work and home. These included adapting technical and design components of both the poster and the feedback systems to a low resource setting and using multiple routes including informal messaging and collegial relationships to cast a wide net for feedback. During the period of 8–26 May 2020 when the feedback form was available on the website, there was an increase of over 600% in website traffic compared to the previous month, with a mean of 15.08 web page views per day. Access from non‐regional locations including Lima, Bangkok and Kathmandu, suggested a broader level of interest.

The result of this collaborative process is the Health Worker Safety Guide for COVID‐19, a poster that assists HCW in PIC to reduce the risk of transmission of infection between home and work. The guideline has been endorsed by both ACEM and the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC), the principal regional scientific, technical and international development organisation. SPC has disseminated the poster to clinical networks and health ministries across the Pacific region. It has also been shared at each GECCo forum and features on the ACEM website enabling global accessibility. 9

The poster remains a live resource that has currently been translated into three Pacific languages. The flexible template designed to facilitate easy language translation can also be used to create adaptations for other contexts as required ensuring its ongoing relevance.

EC in the Pacific is a new and rapidly evolving specialty now confronting a global pandemic with limited resources. Developing effective and meaningful collaboration techniques to maximise collegial support requires a flexible, respectful approach. As Peake et al. 10 declared after a similar project, “the resource is a tangible outcome and a major achievement; however, the process of authentic engagement to achieve the final product was the ultimate accomplishment.”

Acknowledgements

The authors' focus during this process has been to empower the involvement of PIC nurses; however, acknowledgement must be made of the significant contribution and support from medical and other staff who participated in every aspect of the process and who recognise the value of nursing knowledge and the backbone of EC it provides in the Pacific.

Author contributions

AG, BG, GP conceived the paper, with AG, BG, DdS performing all collection, analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper and approved the final version for publication.

Competing interests

GP is a section editor for Emergency Medicine Australasia.

Angela Gittus, BN, MPH&TM, Clinical Nurse Specialist; Bronwen Griffiths, BA, PGDipAppSci (Nurs), MPH, Clinical Nurse Specialist; Dominic de Salis, BParamed, Paramedic; Georgina Phillips, MBBS, FACEM, PhD Scholar, Emergency Physician.

References

- 1. Australasian College for Emergency Medicine . ACEM supports low and middle income countries through COVID‐19 . 2020. [Cited 9 Feb 2021.] Available from URL: https://acem.org.au/News/April‐2020/GECCO‐and‐COVID‐19

- 2. Phillips G, Creaton A, Airdhill‐Enosa P et al. Emergency care status, priorities and standards for the Pacific region: a multiphase survey and consensus process across 17 different Pacific Island countries and territories. Lancet Regional Health 2020; 1: 100002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pacific Research and Policy Centre and the Pasifika@Massey Directorate. Pacific Research Guidelines and Protocols . 2017. [Cited 11 Jan 2021.] Available from URL: https://www.massey.ac.nz/massey/fms/Colleges/College%20of%20Humanities%20and%20Social%20Sciences/pacific‐research‐and‐policy‐centre/192190%20PRPC%20Guidelines%202017%20v5.pdf?4D6D782E508E2E272815C5E3E1941390

- 4. Tassicker B, Tong T, Ribanti T, Gittus A, Griffiths B. Emergency care in Kiribati: a combined medical and nursing model for development. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2019; 31: 105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific . Broadband connectivity in Pacific Island countries. 2018. [Cited 24 Mar 2021.] Available from URL: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/Broadband%20Connectivity%20in%20Pacific%20Island%20Countries.pdf

- 6. Kjellstrom S, Mitchell A. Health and healthcare as the context for participatory action research. Action Res. 2019; 17: 419–28. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turale S, Kunaviktikul W. The contribution of nurses to health policy and advocacy requires leaders to provide training and mentorship. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2019; 66: 302–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ekeroma A. Collaboration as a tool for building research capacity in the Pacific Islands. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2018; 45: 295–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Australasian College for Emergency Medicine . ACEM Resources . [Cited 2 Feb 2021.] Available from URL: https://acem.org.au/Content‐Sources/Advancing‐Emergency‐Medicine/COVID‐19/Resources/ACEM‐Resources

- 10. Peake R, Jackson D, Lea J, Usher K. Meaningful engagement with aboriginal communities using participatory action research to develop culturally appropriate health resources. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2020; 32: 1043659619899999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]