Abstract

Background

During Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak in Lombardia, people were recommended to avoid visiting emergency departments and attending routine clinic visits. In this context, it was necessary to understand the psychological reactions of patients with chronic diseases. We evaluated the psychological effects on patients with chronic respiratory conditions and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) through the analysis of their spontaneous contacts with their referral centres.

Methods

Cross‐sectional study was conducted from February 23 to April 27, 2020 in patients, or their parents, who contacted their multidisciplinary teams (MDT). E‐mails and phone calls directed to the MDT of the centre for cystic fibrosis (CF) in Milano and for paediatric IBD in Bergamo, were categorised according to their contents as information on routine disease management, updates on the patient's health status, COVID‐19 news monitoring, empathy towards health professionals, positive feedback and concern of contagion during the emergency.

Results

One thousand eight hundred and sixteen contacts were collected during the study period. In Milano, where the majority of patients were affected by CF, 88.7% contacted health professionals by e‐mail, with paediatricians receiving the largest volume of emails and phone calls compared with other professionals (P< .001). Compared with Milano, the centre for IBD in Bergamo recorded more expression of empathy towards health professionals and thanks for their activity in the COVID‐19 emergency (52.4% vs 12.7%, P< .001), as well as positive feedback (64.3% vs 2.7%, P = .003).

Conclusion

One of the most important lessons we can learn from COVID‐19 is that it is not the trauma itself that can cause psychological consequences but rather the level of balance, or imbalance, between fragility and resources. To feel safe, people need to be able to count on the help of those who represent a bulwark against the threat. This is the role played, even remotely, by health professionals.

What’s known

Data on psychological reactions to COVID‐19 in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) are scarce.

Updated PubMed search on September 18, 2020, with the key terms “cystic fibrosis,” “psych*” and “COVID‐19” identified only a few studies yet.

One Italian study involving healthy adolescents reports an excellent ability to manage situations of insecurity and to deal with unfavourable and adverse conditions by adapting to the new routine.

What’s new

This is the only study evaluating in a real context created by the COVID‐19 outbreak in Lombardia, the spontaneous reactions of patients affected by chronic diseases and their parents, voluntarily expressing their emotions and needs without any stimulus induced by researchers.

As proposed by the available evidence, telemedicine might be useful to preserve the chronic care model even remotely; however, it should be an adjuvant help not tout court a substitute of the face‐to‐face interaction.

1. INTRODUCTION

December 2019 marked the beginning of the most impressive pandemic of the 21st century caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). 1 This pandemic had its first outbreak in the Wuhan region. 2 The second outbreak occurred in Lombardia (Northern Italy) which, to date, can count 102,303 cases of infection and 16,891 deaths, 3 with higher fatality rates in individuals with comorbidities. 4 The pandemic had a big epicentre in the Bergamo province where mortality rose +568% in the first trimester of 2020 if compared with the first trimester of the previous 4 years. 5

Lombardia started from March 9 the lockdown period, which lasted until May 4 when a phase‐II started with a gradual reopening of working activities. However, several measures to contain the spread of infection such as social distancing, use of face masks, ban on activities involving the participation of groups of people and closure of schools were protracted for several weeks beyond.

In particular, inhabitants of the Bergamo province describe the lockdown period as very frightening and characterised by a deep silence that was only broken by the sound of ambulances.

This situation, perceived as a serious public health emergency, posed a great challenge to people's resilience with possible psychological consequences.

Even if after disasters most people are resilient and do not succumb to psychopathology and, indeed, may find new strengths, 6 some other groups of people—specially those affected with chronic diseases such as Rheumatoid Arthritis or Systematic Lupus Erythematosus 7 —are more vulnerable to psychological and social effects of a pandemic. 8 For instance, people who developed neuropsychiatry sequelae after being hospitalised in isolation facilities because of severe COVID‐19 illness. 9 We focused our attention on patients living in the Lombardia area with two distinct chronic diseases in order to define the eventual difference in the reaction of patients and their families.

The first group is composed of patients affected by cystic fibrosis (CF), which is the most frequent potentially lethal inherited disease amongst Caucasians, whose morbidity and mortality are mainly related to lung disease. 10 , 11 The second group is composed of children affected by inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), a group of immune‐mediated gastrointestinal disorders that require, in the majority of cases, the use of immunomodulatory treatments to control symptoms related to chronic gut inflammation. The Lombardia regional referral centre for CF in Milano and the referral centre for paediatric IBD in Bergamo were identified as the best setting for the present research, under the hypothesis that the different geographical or clinical contexts drive different reactions of patients and parents.

In this paper, we analyse the type of contacts we had with patients with CF and IBD and their families, during the lockdown period for the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19). We also focused on the psychologically relevant contents of these contacts.

2. METHODS

This was an observational study performed at the Cystic Fibrosis Regional Reference centre in Milano, and at the referral centre for paediatric IBD in Bergamo, starting from February 23 to April 27, 2020.

We prospectively extracted the contents of e‐mails and phone calls into ad hoc database, according to the purpose of the contact. These were categorised as information on routine disease management, updates on the patient's health status, COVID‐19 monitoring, empathy towards health professionals, positive feedback and concern of contagion during the emergency. Patients’ demographics were retrieved from electronic medical records available at the clinics, for which consent was already obtained.

2.1. Organisational changes because of COVID‐19 at CF and IBD centres

The standard activity at the CF centre was limited to emergencies, with elective activities, such as routine respiratory function and microbiology tests, postponed preventing unnecessary hospital visits and viral spread. We recommended, in agreement with the extraordinary measures implemented by the Italian Government to reduce transmission, staying at home and adopting all preventive measures. 12 However, communication with the multidisciplinary team (MDT) remained open through phone calls and e‐mails in order to monitor the health and psychological well‐being of the patients. Nurses called families to postpone routine clinical appointments. During their phone calls, they informed patients and parents that the centre was open, the paediatricians and all MDT members active and available for both phone calls and e‐mails. Paediatricians (n = 7) remained available for telephone calls every day between 11:00 am and 1:00 pm, physiotherapists (n = 2) and one dietician were available for telephone calls everyday during office time. The psychologist, being involved in scheduled support interviews and maintenance psychotherapy sessions delivered through phone calls and video calls, remained available for calls without an appointment from Monday to Friday from 2:00 pm to 4:00 pm Differently, patients could leave messages to the secretary and the suitable health professional called back the patient. It is worth mentioning that at the CF centre, patients with other chronic lung diseases (CLD) than CF, as well as patients with gastrointestinal disorders, are in regular follow‐up.

While most of the patients from Milano contacted their MDT on their own initiative, patients from Bergamo were initially contacted by their physicians to assess patients’ health. Patients with IBD from Bergamo received an e‐mail from their MDT between the end of March and the first decade of April 2020, reassuring them that they were not at increased risk to be affected by COVID‐19 as a result of immunomodulatory treatments they were prescribed. 13 The MDT was composed of two paediatricians, one specialised nurse and two psychologists.

Patients with IBD were also asked to inform their IBD centre if they had fever, cough, cold, diarrhoea, vomiting, loss of taste and smell, if they had any contact with people surely affected by COVID‐19 and about their flu vaccination status.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Metrics are reported as mean and standard deviation or counts and percentage, as appropriate. Chi‐square test was used to assess difference between categorical variables. Fisher's approach to compute exact P‐value was used for post hoc test. 14 For two‐way multiple response table, 15 chi‐square test with Bonferroni adjusted P‐values (alpha = 0.008) was used to test differences between Milano and Bergamo centres. Loess regression line was used to visually assess the relationship between the number of contacts and time in each considered group‐age subset. For all analyses, P‐value were two‐sided and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using the open‐source software R Core Team, version 3.6.2. 16

3. RESULTS

We analysed the contents of 1867 e‐mails and phone calls from 654 patients from Bergamo and Milano, as reported in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients followed‐up at the referral centres of Milano and Bergamo and their contacts

| Bergamo (n = 61) | Milano (n = 593) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBD | CF (n = 510) | CLD (n = 48) | GD (n = 35) | |

| Age, mean(SD), y | 15.2 (2.8) | 15.5 (10.1) | 13.9 (6.9) | 9.4 (5.5) |

| Age, min‐max, y | 7‐18 | 0.2‐55.2 a | 1.9‐31 | 0.4‐19.6 |

| Sex, F/M | 24/37 | 847/826 | 38/44 | 25/26 |

| Contacts, No. (%) | ||||

| No. e‐mail | 42 (68.9) | 1188 (71.0) | 60 (73.2) | 48 (94.1) |

| No. phone calls | 19 (31.1) | 485 (29.0) | 22 (26.8) | 3 (5.9) |

| Contacts directed to MDT, No. (%) | ||||

| Dietitians | — | 139 (8.3) | — | — |

| Paediatrician | 61 (100) | 1493 (89.2) | 82 (100) | 51 (100) |

| Physiotherapists | — | 41 (2.5) | — | — |

Abbreviations: CF, cystic fibrosis; CLD, chronic lung disease; GD, gastrointestinal disorder; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; MDT, multidisciplinary team.

Some adult patients with CF were temporarily followed‐up at the paediatric CF centre because of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Because the most severe form of COVID‐19 has a pulmonary expression, our analysis considers patients from Milano with CF and CLD together. The majority (88.7%, 495/558) contacted health professionals by e‐mail, with paediatricians receiving the largest volume of e‐mails and phone calls compared with other professionals (P < .001).

During the study period, 56.1% of contacts sent by parents of infants (78/139) were directed to the dietician. In contrast, the majority of contacts from other age groups, including toddlers were addressed to paediatricians. Amongst contacts directed to physiotherapists, the majority (20/41, 48.8%) came from adult patients. An association was found between age of the patients and health care professionals more frequently contacted (P < .001): infants contacted dietician more frequently (P < .001) whereas toddlers, school‐aged and adults contacted more the medical team (P < .001). There were no sex‐related differences in the number of contacts (885, 50.4% from females and 870, 49.6% from males, P = .720). Calls or e‐mails arriving from adult patients accounted for more than one‐third (36.2%) of contacts, whereas contacts by parents of school‐aged children (27.8%), of preschoolers (11.8%) and infants (7.4%) were lower.

Considering that the greatest number of contacts were directed to paediatricians, we further analyse these data. During the study period, 547 patients (275 females) stayed in touch with the medical team. Four hundred and eighty‐seven choose a contact by e‐mail and 195 by phone call. The total number of e‐mails sent was 1191, whereas we counted 384 phone calls (1575 contacts overall).

The majority of contacts were repeated more than three times (71.9%); 37.1% of patients contacted the CF centre once, with an overall median (IQR) contact frequency of 2(3) (min‐max 1‐16).

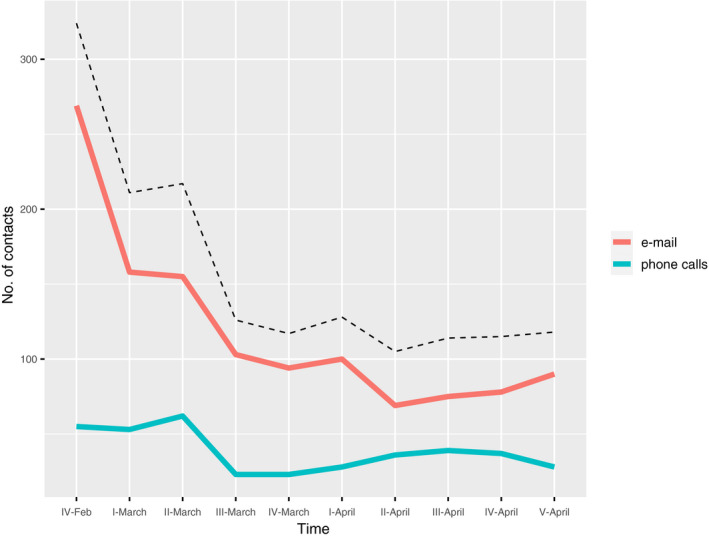

The number of contacts was higher during the first weeks, as shown in Figure 1, with a total of 269 e‐mails and 55 phone calls just during the first one (February 21 to 29, 2020). More than one‐third of contacts addressed to the medical team (37.1%) were about COVID‐19.

FIGURE 1.

Number of contacts directed to paediatricians during the study time (expressed in weeks). Dashed line denotes the sum of e‐mails and phone call contacts. Peak during the second week of March (ie, II‐March) denotes the week in which lockdown was declared (March 9, 2020)

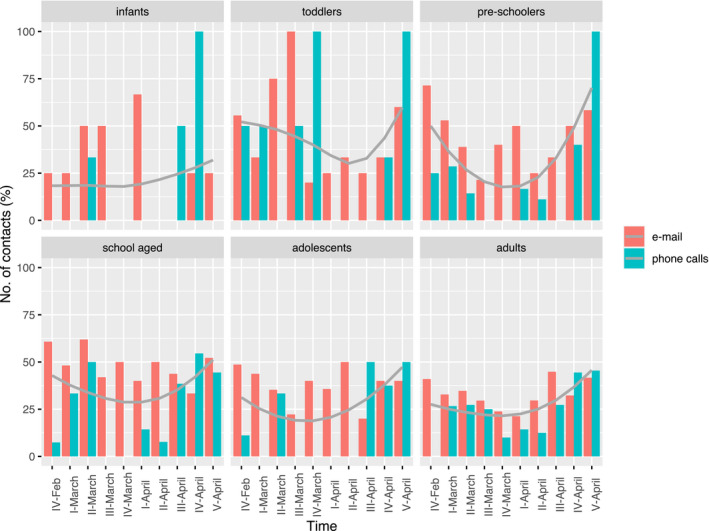

Along the weeks, patients with different ages showed the same pattern in the number of contacts towards the CF medical team about COVID‐19 (Figure 2). Overall, the number of contacts for any reason was not associated to the age group (P = .203).

FIGURE 2.

Number of contacts directed to paediatricians during the study period stratified by age groups and the type of contacts. The curved solid grey lines represent nonparametric regressions

A deeper look at the data revealed qualitative differences amongst the exchanges with the different professionals of the MDT. Since January 1, 2020 physiotherapists received 199 e‐mails, 84 (42%) of them between February 21 and April 16, 2020. The vast majority of requests were related to broken or to be renewed materials, and to the type of physical activity to do at home in order to maintain an adequate exercise level. The same contents regarded the received phone calls (about 3 daily). The length of calls to paediatricians varied considerably between a few minutes to more than half an hour, as reported also by the dietician whose calls, since April 6, became considerably longer, even exceeding 40 minutes.

From February 21 to March 6, 2020, the psychologist maintained regular sessions for those few patients on treatment who wanted to come to the centre as usual. Since March 9, 2020, with the temporary cancellation of the outpatient activity, the psychologist maintained contacts with patients in regular psychological treatment through phone calls or video calls according to the patient's preference.

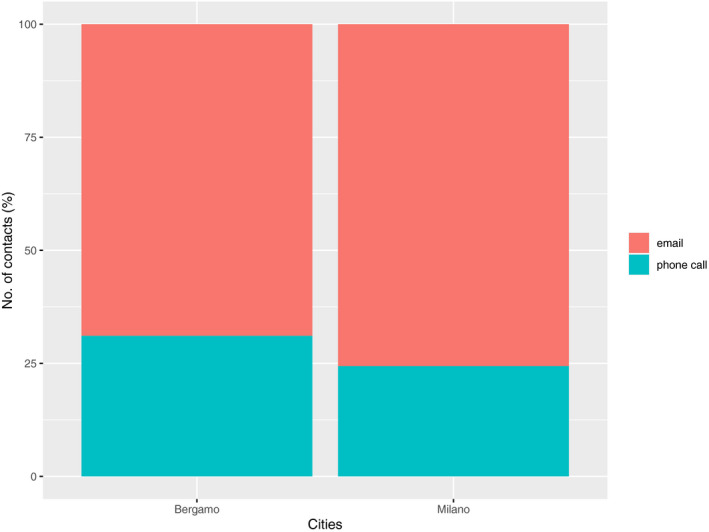

As far as the Bergamo centre patients are considered, 42 e‐mails and 19 telephone calls were performed covering the whole group of patients in regular follow‐up (Table 1). Figure 3 depicts the distribution of contacts directed towards paediatricians in Bergamo compared with Milano. No significant differences were detected (P = .293). Further comparison between patients from Milano and Bergamo was carried out regarding the contents of e‐mails (Table 2). In Bergamo, where the pandemic took so many victims, we received much more expression of empathy towards health professionals and thanks for their activity in the COVID‐19 emergency than in Milano, where the death toll was lower. The same can be said about the positive feedback given as well as updates on patients’ health status.

FIGURE 3.

Frequency of e‐mails and phone calls towards the medical team from Milano and Bergamo

TABLE 2.

Contents of the e‐mails sent to the medical team by patients with CF and CLD (n = 487) and patients with IBD (n = 42) a

| Bergamo (n = 42) | Milano (n = 487) | P Value b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Request for information on the therapies to be done or in progress and appointments for regular follow‐up | 17 (40.5) | 225 (46.2) | 1.00 |

| Updates on the patient's health status | 32 (76.2) | 178 (36.3) | <.001 |

| Request for information/reassurance regarding the emergency from COVID pandemic | 16 (38.1) | 297 (61.0) | .023 |

| Empathy towards health professionals and thanks for their activity in the COVID emergency | 22 (52.4) | 62 (12.7) | <.001 |

| Positive feedback for communications from carers perceived as reassuring | 27 (64.3) | 13 (2.7) | .003 |

| Concern/fear of contagion during the emergency because of the patient's state of health | 16 (38.1) | 171 (35.9) | 1.00 |

Data are reported as No. (%) where (%) are column percent of patients.

Bonferroni adjusted P values.

4. DISCUSSION

We analysed the contacts directed to the MDTs in Milano and Bergamo assuming the influence of the specific pandemic scenarios on patients’ behaviour, knowing that patients with respiratory diseases felt vulnerable for their lung condition, whereas patients with IBD felt themselves at risk because of immunomodulatory treatments. Recommendations to prevent contagion and fear of being infected prevented patients from visiting emergency departments even when necessary. 17 Patients followed up at our clinics did their best to avoid unnecessary access to hospital, and remained at home as recommended, delaying scheduled visits.

Our findings demonstrate how much the context drove the exchanges with patients and parents. When exposed to the whims of an invisible and deadly enemy meandering in the neighbourhood, help, even from virtual contact with people known and trusted, balance fears connected to running a risk of death. We remember that population in Lombardia—and above all the population of the province of Bergamo—found themselves confined at home, often without the support of family doctors (several died because of the pandemic). In addition, mass media bombarded the population with images of a large number of coffins and news about the insufficient number of intensive care beds for the huge number of people affected by COVID‐19. Feeling in danger in such a situation is an appropriate, healthy reaction, which is governed by the motivational defence system (fight, flight, freezing). 18 The vast majority of people able of showing good defences manage to survive the traumatic experience and return to their lives by demonstrating their resilience.

The relevance of the context in driving people's reactions is also demonstrated by the fact that the request for information and reassurances regarding the emergency from the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic was significantly more frequent in Milano, where patients and families had access to their MDT, whereas the positive feedback was greater in Bergamo, where patients and families were more worried for their MDT survival. It was soon clear that if the pandemic in Milano had had the same dimensions as in it occurred in Bergamo, the disaster would have been even bigger and more impressive, given that Milano is a big city with 1.4 million inhabitants while Bergamo has 120 000.

During the present pandemic, people could have a different psychological impact depending on related stressors, including exposure to infected sources, infected family members, loss of loved ones, physical distancing; economic loss; psychosocial effects (depression, anxiety, psychosomatic preoccupations, insomnia, increased substance use, domestic violence). Pre‐existing physical or psychological conditions could be included too. 8 In most of the contacts, paediatricians were asked if and how many patients with CF had COVID‐19. The underlying concern was clear that patients with a chronic condition may be more vulnerable and therefore there was a fear of learning that some had died because of pandemic. The news that none of our patients died of the pandemic was a great relief, especially for parents.

A recent review of psychological sequelae in quarantined people and health care providers revealed different outcomes according to the different perspectives of analysis and the different populations considered. 10 Specific stressors included greater duration of confinement, having inadequate supplies, difficulty securing medical care and medications, and resulting financial losses. Higher number of children, 19 facing discrimination, 20 frequent exposure to social media/news concerning COVID‐19, 21 and low confidence in health services 22 are described as potential stressors as well. Indeed, the prolongation of the lockdown in Lombardia has made the strain of social isolation increasingly felt, especially for mothers of children under 2 years of age accustomed to coming to the CF centre at least once a month. Given the importance of nutrition in young children to ensure adequate growth, mothers of preschoolers were the ones who had the most frequent contacts with dieticians. Also, in the dietician's experience, the context appeared extremely relevant: the families in the province of Bergamo were more challenged, worried and scared. In fact, in that area, each family has acquaintances or relatives hospitalised or deceased for COVID‐19. This shaped their experience of the pandemic in a peculiar and very different way from those who listened to the news provided by the mass media. The parents of younger patients were so worried about the risk of contagion for their children that so many of them wore the facial mask even at home all day. The same can be said for parents who had to look after more than one child: the long quarantine put a strain on some families who could not count on the help of grandparents and institutions such as schools and kindergartens.

Generally, crucial aspects of patients’ worries are connected, first, with the closeness to people infected. Parents leaving in the Bergamo area resulted in most worried and frightened by the situation surrounding their families. These parents expressed the most distressing experiences and the highest fears for their children's well‐being. The same fears were expressed by parents, even those not living in the Bergamo area, who had experiences of infection in their group of relatives.

Disaster medicine developed plans to tackle major emergencies which, however, showed to be ineffective to face events with the shape of public health and humanitarian crisis such as that induced by COVID‐19. 23 Social distancing is fundamental, undermining the greatest resource of humans that is the support coming from the proximity of other people. Even adherence is better. For humans, the best counter poison against non‐adherence is the relationship with expert health teams. Interestingly, data from physiotherapists at the CF centre revealed a peculiar aspect of this pandemic time. Both e‐mails and phone calls were aimed at asking the sequence of physiotherapy actions. Considering that these are patients accustomed to following a home physiotherapy programme and well aware of the sequence of actions to be followed, this type of request clearly indicates a need for contact with trusted health workers rather than a genuine question about how to do physiotherapy at home.

In this scenario, to reduce the psychological impact it is important to ensure accurate updated specific information and to provide special precautionary measures in order to help the population to reduce the level of anxiety for their health and the risk of contagion 24 , 25 , 26 Such information includes the number of recovered cases, treatments available or understudy, mode of transmission, number of infected cases and their location. 25 Also, in the 2009‐2010 H1N1 influenza, the need for a vaccine and reliable health information about the virus and its potential consequences demonstrated its relevance for the public to lower stress and anxiety. 27

A long‐term plan for the next pandemic is clearly needed 23 for population and patients with chronic diseases for whom MDT demonstrated to be a crucial resource. This epidemic is imposing on our health system a level of stress no longer sustainable, with the burden of so many deaths, even of young and healthy people, and whole generations of elderly people; our communities are suffering fear, isolation and uncertainty for the future.

Amongst the limitations, as regards external validity, our study reflects the practice of two referral centres for chronic diseases in the North of Italy and likely mirrors the practice of other Italian referral centres during the outbreak of the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic, although the context of Lombardia was dramatically unique. As regards the internal validity, we acknowledge that contacts, as classified in the present study, were not independently assessed, and reflect the categorisation proposed by the clinical psychologists of the centres for CF and IBD.

5. CONCLUSION

An important lesson we can learn from the pandemic is that it is not the trauma itself that can cause psychological consequences but the level of balance, or imbalance, between fragility and resources. To feel safe, people need the help of those who represent a bulwark against the threat. This is the role played even remotely by health professionals. The fear evoked by the danger makes everyone either trusting their own resources and using their coping strategies at best or feeling overwhelmed.

Health professionals investing in the human relationship with patients and families, even remotely, provide a secure base for their patients, acting as a guarantee of help and guidance, in addition to specific professional competence.

The pandemic has shown the importance of investing in health as a real resource, not only for those who have been affected but also for all those who have seen their world and their habits upset, also by alarmism and incorrect news.

A strong group of cohesive professionals has the tools to support resilience in themselves and in their patients. This is why MDT should be considered a model not only for chronic diseases but for any health context that welcomes the fragility and pain of humans.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Nobili RM, Gambazza S, Spada MS, et al. Remote support by multidisciplinary teams: A crucial means to cope with the psychological impact of the SARS‐COV‐2 pandemic on patients with cystic fibrosis and inflammatory bowel disease in Lombardia. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e14220. 10.1111/ijcp.14220

Rita Maria Nobili and Simone Gambazza contributed equally as first author.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [RMN], upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhou P, Lou YX, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270‐273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Phelan AL, Katz R, Gostin LO. The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China: challenges for global health governance. JAMA. 2020;323:709‐710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coronavirus Disease (Covid‐19) . http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?area=nuovoCoronavirus&id=5351&lingua=italiano&menu=vuoto. Accessed September 10, 2020.

- 4. Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID‐19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. 2020;395:1225‐1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fagiuoli S, Lorini FL, Remuzzi G. Adaptations and lessons in the province of Bergamo. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buzzi C, Tucci M, Ciprandi R, et al. The psycho‐social effects of COVID‐19 on Italian adolescents’ attitudes and behaviors. Ital J Pediatr. 2020;46:4‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tee ML. Psychological state and associated factors during the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) pandemic among Filipinos with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the covid‐19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:510‐512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hao F, Tam W, Hu X, et al. A quantitative and qualitative study on the neuropsychiatric sequelae of acutely ill COVID‐19 inpatients in isolation facilities. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912‐920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bell SC, Mall MA, Gutierrez H, et al. The future of cystic fibrosis care: a global perspective. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:65‐124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Colombo C, Burgel P‐R, Gartner S, et al. Correspondence Impact of COVID‐19 on people with cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2020;2600:19‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Norsa L, Indriolo A, Sansotta N, Cosimo P, Greco S, D’Antiga L. Uneventful course in patients with inflammatory bowel disease during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 outbreak in northern Italy. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:371‐372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shan G, Gerstenberger S. Fisher’s exact approach for post hoc analysis of a chi‐squared test. PLoS One. 2017;12:1‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jann B. Tabulation of multiple responses. Stata J. 2005;5:92‐122. [Google Scholar]

- 16. R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; 2019. https://www.r‐project.org

- 17. Lazzerini M, Barbi E, Apicella A, Marchetti F, Cardinale F, Trobia G. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID‐19. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2020;4:e10‐e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cortina M, Liotti G. An evolutionary outlook on motivation: implications for the clinical dialogue an evolutionary outlook on motivation: implications for the clinical dialogue. Psychoanal Inq. 2014;34:864‐899. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Le XTT, Dang AK, Toweh J, et al. Evaluating the psychological impacts related to COVID‐19 of Vietnamese people under the first nationwide partial lockdown in Vietnam. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tan W, Hao F, Mcintyre RS, Jiang L, Jiang X, Zhang L. Is returning to work during the COVID‐19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav Immun J. 2020;87:84‐92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, et al. Impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55‐64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID‐19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:40‐48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nacoti M, Ciocca A, Giupponi A, et al. At the epicenter of the covid‐19 pandemic and humanitarian crises in Italy: changing perspectives on preparation and mitigation. NEJM Catal. 2020;1:1‐5. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ho CS, Chee CY, Ho RC. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID‐19 beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2020;49:155‐160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leung CC, Lam TH, Cheng KK. Mass masking in the COVID‐19 epidemic: people need guidance. Lancet. 2020;395:945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pfefferbaum B, Schonfeld D, Flynn BW, et al. The H1N1 crisis: a case study of the integration of mental and behavioral health in public health crises. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2012;6:67‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [RMN], upon reasonable request.