Abstract

Basic helix-loop-helix proteins (bHLHs) comprise one of the largest families of transcription factors in plants. They have been shown to be involved in responses to various abiotic stresses, such as drought, salinity, chilling, heavy metal toxicity, iron deficiency, and osmotic damages. By specifically binding to cis-elements in the promoter region of stress related genes, bHLHs can regulate their transcriptional expression, thereby regulating the plant’s adaptive responses. This review focuses on the structural characteristics of bHLHs, the regulatory mechanism of how bHLHs are involved transcriptional activation, and the mechanism of how bHLHs regulate the transcription of target genes under various stresses. Finally, as increasing research demonstrates that flavonoids are usually induced under fluctuating environments, the latest research progress and future research prospects are described on the mechanisms of how flavonoid biosynthesis is regulated by bHLHs in the regulation of the plant’s responses to abiotic stresses.

Keywords: plant, bHLH transcription factor, flavonoids, abiotic stresses, cis-elements

Introduction

Basic helix-loop-helix proteins (bHLHs), are one of the largest transcription factor (TF) families. They are widely distributed in plants, fungi, and animals (Riechmann and Muyldermans, 1999; Carretero-Paulet et al., 2010). In Ludwig et al. (1989), the first plant bHLH TF was observed in maize. Since then, a great many bHLHs have been proven to regulate plant responses to various abiotic stresses. bHLHs are involved in regulating the synthesis of flavonoids (Ludwig et al., 1989), which play important roles in the ROS homeostasis under these stresses. As an illustration of the size of the bHLHs family in various plant species, 164 bHLH TFs have been found in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana L.), while there are 180 in rice (Oryza sativa L.), 190 in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.), 191 in grapes (Vitis vinifera L.), 102 in walnut (Juglans regia L.), 85 in Ginkgo biloba, 268 in Brassica oleracea, 440 in Brassica napus, and 251 Brassica rapa (Xiong et al., 2005; Jaillon et al., 2007; Rushton et al., 2008; Carretero-Paulet et al., 2010; Miao et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021).

TFs, also known as trans-acting factors, are a category of proteins that specifically bind to cis-acting elements in the promoter region of eukaryotic genes. They regulate specific physiological or biochemical processes in cells at the transcriptional level. The protein structure of TFs generally contains four functional domains: a DNA-binding domain, a transcriptional regulation domain, an oligomerization site, and a nuclear localization domain. The transcriptional regulatory domain may include both an activation domain and an inhibitory domain (Yang et al., 2020).

The bHLH transcription factor conservatively contains two connected sub-regions, the N-terminal basic region directly followed by the HLH (helix-loop-helix) domain (Atchley et al., 1999). More than 50% of bHLHs that have been found in plants possess a highly conserved HER motif (His5-Glu9-Arg13) to achieve DNA binding and regulate the transcription of their target genes (Atchley and Fitch, 1997; Massari and Murre, 2000; Toledo-Ortiz et al., 2003). The HLH region is composed of 40∼50 amino acid residues, which is required for the formation of dimers (Sharker et al., 2020).

The animal bHLHs were first categorized into six subfamilies (A∼F) by Atchley et al. (1999) based on characteristics of the HLH and other conversed domains. The phylogenetic tree of plant bHLH was first constructed in Arabidopsis thaliana. The bHLH family of Arabidopsis was divided into 12 subfamilies (Gao et al., 2017). Later, these subfamilies were expanded into 32 subgroups by phylogenetic analysis based on the 638 bHLH genes extracted from Arabidopsis, Populus trichocarpa, Oryza sativa, Physcomitrella patens, and five algae species (Carretero-Paulet et al., 2010). Evolutionary and functional relationships within subfamilies are supported by intron patterns, predicted DNA-binding motifs, and the architecture of conserved protein motifs. Some subfamilies may modulate biological responses critically for the development of terrestrial plants.

Regulatory Mechanism of bHLHs Involved in Transcriptional Activation

As one of the largest TF families, bHLHs regulate the expression of downstream target genes usually in a binary or ternary complex form (Figure 1). The ternary MBW complex has been analyzed extensively in various biological processes (Dixon et al., 2005; Shoji and Hashimoto, 2011; An et al., 2012). The bHLH proteins of the IIIf subgroup (TT8, GL3, EGL3, and AtMYC1) can interact with R2R3-MYBs from various subgroups (TT2, PAP1, or PAP2), and form ternary complexes with a WD-repeat protein (TTG1) (Baudry et al., 2004). The MYB5-TT8-TTG1 complex is activated in the endothelium to regulate DFR (dihydroflavonol reductase), LDOX (leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase), and TT12 expression, whereas the TT2-EGL3/GL3-TTG1 complexes regulate the expression of LDOX, BAN (BANYULS; anthocyanidin reductase), AHA10 (autoinhibited H+-ATPase isoform 10), and DFR in the chalaza (Xu et al., 2015). Regulatory complexes composed of MYB10, bHLH3, and WD40 may control the biosynthesis of anthocyanins in peaches (Ravaglia et al., 2013). BoPAP2 (MYB), BoTT8, BoEGL3.1, BoMYC1.2 (bHLH), and BoTTG1 (WD40) have been identified as candidate genes for regulating anthocyanin biosynthetic activity in cabbage (Jin et al., 2018).

FIGURE 1.

Different regulatory patterns of bHLH transcription activation.

There are also many studies that address the activation mechanism of the MYB-bHLH binary complex (Zimmermann et al., 2004). The C-terminal domain of many bHLHs have been found to contain a MYB-binding site. Through binding to this site, MYB could heterodimerize with bHLHs (Heim et al., 2003). For example, VvMYC1 in grapes cannot activate the promoters of CHI, UFGT, and ANR genes in the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway by itself, but the co-transfection of VvMYC1 with a MYB transcription factor can significantly activate the expression of the genes for these three enzymes (Hichri et al., 2010). Rosea1 (ROS1, MYB-type) and Delila (DEL, bHLH-type) from Snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus) can specifically induce anthocyanin accumulation when co-expressed in tomato fruits (Outchkourov et al., 2014). Xiang et al. (2015) found that CmbHLH2 significantly upregulated CmDFR transcriptional expression and triggered anthocyanin accumulation when co-expressed with CmMYB6. Using transient assays in both Nicotiana tabacum leaves or Actinidia arguta fruits and stable transformation in Arabidopsis, Wang et al. (2019) demonstrated that co-expression of AcMYB123 and AcbHLH42 is a prerequisite for anthocyanin production by activating transcription of AcF3GT1 and AcANS or their homologous genes. Li L. et al. (2019) found that AabHLH1 interacted with AaMYB3 to regulate the accumulation of procyanidine. In addition, DhMYB2 interacted with DhbHLH1 to regulate anthocyanin production in Dendrobium hybrid petals (Li et al., 2017). As well, the bHLH transcription factor PPLS1 interacts with SiMYB85 to control the color of leaf sheath and pulvinus by regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis in Setaria italica (Bai et al., 2020).

The transcriptional activities of bHLHs can also be regulated through dimerization, and a series of post-translational modifications including phosphorylation and ubiquitination (Figure 1; Xu et al., 2015). The Arabidopsis bHLH transcription factor FER-LIKE IRON DEFICIENCY-INDUCED TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR (FIT) displays a pivotal role in the Fe-deficiency response, and its activity is regulated by heterodimerizing with bHLH039 (Gratz et al., 2019). Interestingly, this heterodimerization capacity is affected by differential phosphorylation. Specifically, the heterodimerization is activated through Ser and deactivated through Tyr site phosphorylation (Gratz et al., 2020). Another Arabidopsis bHLH transcription factor, SPEECHLESS (SPCH), initiates the stomatal lineage (Simmons and Bergmann, 2016). Recent research revealed that the protein stability of SPCH could be positively regulated by phosphorylation mediated via the MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE (MAPK) cascade or GSK3-like kinase BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 2 (BIN2) protein phosphatase 2A phosphatase (Yang et al., 2015; Bian et al., 2020). Chenopodium glaucum CgbHLH001 can positively regulate plant stress tolerance via clearing excessive ROS and accumulating transcripts of stress-related genes (Wang et al., 2017). A recent study indicates that CgbHLH001 activity might be affected by phosphorylation through interaction with CgCDPK (Zhou et al., 2021). Ubiquitination can likewise directly regulate bHLH activity via the 26S proteasome protein degradation pathway (Figure 1). The BTB-BACK-TAZ domain protein MdBT2 in apple can target MdCIbHLH1 for ubiquitination, so as to regulate malate accumulation and vacuolar acidification (Zhang et al., 2020a, b). Pyrus pyrifolia CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (PpCOP1) could ubiquitinate PpbHLH64 and trigger its proteolysis, further reducing the accumulation of anthocyanins (Tao et al., 2020). bHLH activity can also be indirectly regulated by ubiquitination through the degradation of its partners in the MBW complex. The Arabidopsis thaliana MYB Interaction Factor 1 (AtMIF1) is a member of the ubiquitin-protein ligase E3 complex involved in the 26S proteasome protein degradation pathway. AtMIF1 ubiquitinates and degrades AtMYB5, so that transcriptional activation of the MYB/bHLH/WD-repeat (MBW) complex further increases oil content by attenuating GL2 inhibition (Cheng et al., 2021).

The latest reports reveal an emerging regulatory mechanism of MBW transcriptional activation by antagonistic interactions with MBW components (Figure 1). MYB paralogs or ROS-related proteins could disrupt the activated MBW complex by competitively interacting with bHLHs. In Medicago truncatula, two R2R3 MYB paralogs, RED HEART1 (RH1) and RH2, play vital roles in patterned pigmentation. These two antagonistic paralogous proteins competitively bind the MtTT8-MtWD40-1 complex to fine tune the phenotypes of leaf anthocyanin spot marking (Wang et al., 2021). In Zea mays, the ROS-related protein ZmSRO1e (TO RCD-ONEs) interacts with ZmPL1 (MYB)/AtPAP1 (bHLH) to inhibit the formation of an activated MBW complex, thereby repressing the over-accumulation of anthocyanins under abiotic stress (Qin et al., 2021). These two reports provide a multidimensional antagonistic regulatory paradigm for MBW activation. It’s reasonable to speculate that bHLH paralogs or other stress/growth-related proteins might also regulate the MBW activity by competitively interacting with MYB in the complex.

bHLHs Selectively Bind to Particular cis-Acting Elements of Target Genes

The bHLH TFs can form homologous or heterologous dimers and bind to target genes on specific cis-acting elements. Among them, the most frequently studied cis-acting elements are the E-box (5′-CANNTG-3′) and the N-box [5′-CACG(A/C)G-3′] (Li et al., 2006). bHLHs DNA binding domains containing at least five basic amino acids in the N-terminal basic region are expected to bind these DNA motifs (Massari and Murre, 2000).

The E-box is one of the most common targets of the bHLH subfamilies 1 and 27. According to three-dimensional structural analysis of bHLHs, Glu-13 and Arg-16 are essential for E-box-binding recognition (Shimizu et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2003; Carretero-Paulet et al., 2010). This cis-acting element is usually located in the promoter of genes involved in multiple physiological pathways. Nims et al. (2009) found that the yew bHLH TcJAMYC can bind to the E-box in the promotor of paclitaxel-related genes to activate their transcriptional expression. Huang et al. (2013) demonstrated that the Poncirus trifoliata PtrbHLH can bind to an E-box in the promoter region of the POD gene. Wu et al. (2015) showed that the rice OsbHLH062 can bind to an E-box in the promoter of ion transport genes such as OsHAK21. Zhang et al. (2017) found that PnbHLH1 can interact with the E-box core sequence in Panax notoginseng, a traditional Chinese medicine, to induce the triterpenoid saponins. Geng and Liu (2018) experimentally showed that CsbHLH18 bound to the promoter of the sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) CsPOD gene through the E-box. Recent studies have found that GhbHLH18 strongly binds to the E-box in the promoter region of the GhPER8 gene coding for a peroxidase from cotton (Gao et al., 2019). Finally, Chakraborty et al. (2019) demonstrated through DNA-protein interactions both in vitro and in vivo that the bHLH transcription factor MYC2 can bind to the cis-acting E-box element in the HY5 promoter to negatively regulate HY5 expression.

A specific member of the E-box family, the G-box (5′-CACGTG-3′) could be recognized by about 81% of bHLHs (Toledo-Ortiz et al., 2003; Li et al., 2006; Pires and Dolan, 2010) mainly from subfamilies 4, 5, 10, 11, 13, 14, 24, 25, and 26 (Bovy et al., 2002; Yi et al., 2005; Carretero-Paulet et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2018). Qian et al. (2007) confirmed the specific interaction between the pea bHLH transcription factor PsGBF and the G-box of PsCHS1 by transient expression experiments in tobacco. In Arabidopsis, the bHLH transcription factor PIL5 has a high affinity with the G-box as well (Kang et al., 2010). Arabidopsis bHLH106 was characterized through its association with salt tolerance. Transcriptional analysis of an AtbHLH106 overexpression line showed 198 genes positively were regulated and 36 genes were negatively regulated; these genes possessed one or more G-box sequences in their promoter regions, and many of them are associated with the abiotic stress response (Ahmad et al., 2015). Zhang et al. (2011) isolated CrMYC2 from a Catharanthus roseus cDNA library and found that its corresponding protein could specifically bind to G-box of the ORCA3 gene. In addition, tobacco NtMYC2 and NtbHLH123 bind directly to the G-box region of the PMT2 and CBF, respectively, and activated their transcription (Shoji and Hashimoto, 2011; Zhao et al., 2018).Besides, Tamarix hispida ThbHLH1 specifically binds to the G-box of P5CS and the ALDH gene (Ji et al., 2016). The apple MdMYC2 homodimer also binds to the G-box motif of the AtJAZ3 gene (An et al., 2016). Moreover, the Hevea brasiliensis bHLHs HbMYC2, HbMYC3, and HbMYC4 of interacted with the G-box of the HbPIP2 promotor (Zhai et al., 2018).

The N-box is associated with bHLHs possessing an enhancer activity. bHLHs that bind to the N-box usually have a proline in the N-terminal basic domain and a “WRPW” sequence at its C-terminus (Cordeiro et al., 2016). OsPIF14 binds to the OsDREB1B promoter on two N-boxes [CACG(A/C)G] (Cordeiro et al., 2016). Diterpenoid phytoalexin factor (DPF) is a rice bHLH transcription factor which positively regulates CPSCPS2 transcription through N-box binding. DPF can also regulate CYP99A2 through the N-box, thereby affecting the biosynthesis of diterpenoid phytoalexins (DP) (Yamamura et al., 2015). In addition, some bHLHs can bind to other cis-acting elements, for example, AtbHLH112 can not only bind the E-box, but also bind the GCG-box [5′-GG(G/T)CC(G/T)(GA)(TA)C-3′] (Liu et al., 2015).

Heterodimers can be formed between different bHLHs. Fairchild et al. (2000) discovered that two bHLH TFs, PIF3/AtbHLH008 and HFR1, could heterodimerize. This interaction effectively prevented monomer PIF3/AtbHLH008 from binding to the E-box of phytochrome A (phyA), thereby modulating phyA signaling. In addition, bHLHs can heterodimerize with other TFs, such as R2R3-MYB/BZR1-BES1 as well as other signal transduction proteins (Yin et al., 2005; Dubos et al., 2008). The formation of heterodimers makes it possible for different TFs to interact with each other to co-regulate the expression of target genes.

In summary, bHLHs bind directly to cis-elements in the promoter of target genes or form heterodimers to co-regulate their expression. To date, E-box cis-acting elements, in particular, the G-box of this family, are the widest binding targets of bHLHs (Table 1). We found that most bHLHs in subfamilies 1, 2, 12, 13, 15, 19, 24, 25, 26, 27 can bind to the G-box; and members in subfamilies 1, 2, 13, 15, 22, 26, 27 can recognize other cis-elements in the E-box family, except for the G-box; members of subgroup 15 could also bind to the GCG-box (Abe et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2018; Xi et al., 2021).

TABLE 1.

Mechanism of bHLH on transcriptional regulation of target genes.

| cis-acting element | Plant species | Nomenclature | Subfamily | Effect | Referenes |

| E-box, G-box | Arabidopsis thaliana L. | AtbHLH122 | 27 | Participate in drought resistance, salt resistance, osmotic resistance | Liu et al., 2014 |

| E-box, GCG-box | Arabidopsis thaliana L. | AtbHLH112 | 15 | Participate in drought resistance, salt resistance | Liu et al., 2015 |

| G-box | Arabidopsis thaliana L. | AtbHLH106 | 13 | Participate in salt resistance | Ahmad et al., 2015 |

| G-box | Arabidopsis thaliana L. | PIL5/AtbHLH15 | 24 | Unknown | Kang et al., 2010 |

| E-box, G-box | Arabidopsis thaliana L. | AtMYC2/AtbHLH006 | 2 | Involved in niche regulation of root stem cells | Chen et al., 2011; Qi et al., 2015 |

| E-box, G-box | Oryza sativa L. | OsbHLH096 | 26 | Increase phosphorus hunger tolerance | Yi et al., 2005 |

| N-box | Oryza sativa L. | DPF/OsbHLH025 | 7 | Affect DP biosynthesis | Yamamura et al., 2015 |

| E-box | Poncirus trifoliata | PtrbHLH | 1 | Scavenging oxygen free radicals, participate in low temperature resistance | Huang et al., 2013 |

| E-box | Gossypium hirsutum Linn. | GhMYC4 | 2 | Participate in drought resistance, salt resistance | Gao et al., 2016 |

| E-box | Gossypium hirsutum Linn. | GhbHLH18 | 22 | Regulate the content of coniferyl alcohol and sinapic alcohol | Gao et al., 2019 |

| G-box | Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don | CrMYC2 | 2 | Participates in the biosynthesis of terpenoid indole alkaloids | Zhang et al., 2011 |

| G-box | Nicotiana tabacum L. | NtMYC2 | 2 | Regulate nicotine biosynthesis | Shoji and Hashimoto, 2011 |

| E-box, G-box | Nicotiana tabacum L. | NtbHLH123 | 15 | Participate in cold resistance | Zhao et al., 2018 |

| G-box | Betula platyphylla Suk. | BpbHLH7 | 12 | Participates in the synthesis of triterpenoids | Wang et al., 2018 |

| BpbHLH8 | 25 | ||||

| E-box | Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck | CsbHLH18 | 13 | Scavenging oxygen free radicals, participate in low temperature resistance | Geng and Liu, 2018 |

| E-box, G-box | Malus × domestica Borkh. | MdCIbHLH1 | Orphan | Participate in flower bud dormancy and dormancy removal | Ren et al., 2016 |

| G-box | Malus × domestica Borkh. | MdMYC2 | 2 | Participate in the Jasmonic acid (JA) signaling pathway | An et al., 2016 |

| G-box | Medicago truncatula | MtbHLH148 | 19 | Adjust the optical signal response | Wang et al., 2019 |

| G-box | Tamarix hispida Willd. | ThbHLH1 | 26 | Reduce the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) | Ji et al., 2016 |

| G-box | Pisum sativum Linn. | PsGBF | 1 | Unknown | Qian et al., 2007 |

bHLHs Regulate Plant Responses to Various Abiotic Stresses

Previous studies found that bHLHs were involved in a variety of pathways regulating the adaptation to stress in plants, including resistance to mechanical damage, drought, high salt, oxidative stress, low temperature stresses, heavy metal stress, iron deficiency, and osmotic stress (Babitha et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2016). One of the most common responses of plants to stress is to enhance the biosynthesis of different types of compatible organic solutes. In general, this mechanism protects plants from stresses in multiple different ways through regulating cell osmotic homeostasis, eliminating excessive ROS, maintaining the integrity of the plasma membrane, and stabilizing enzymes and structural proteins (Esmaeilpour et al., 2015).

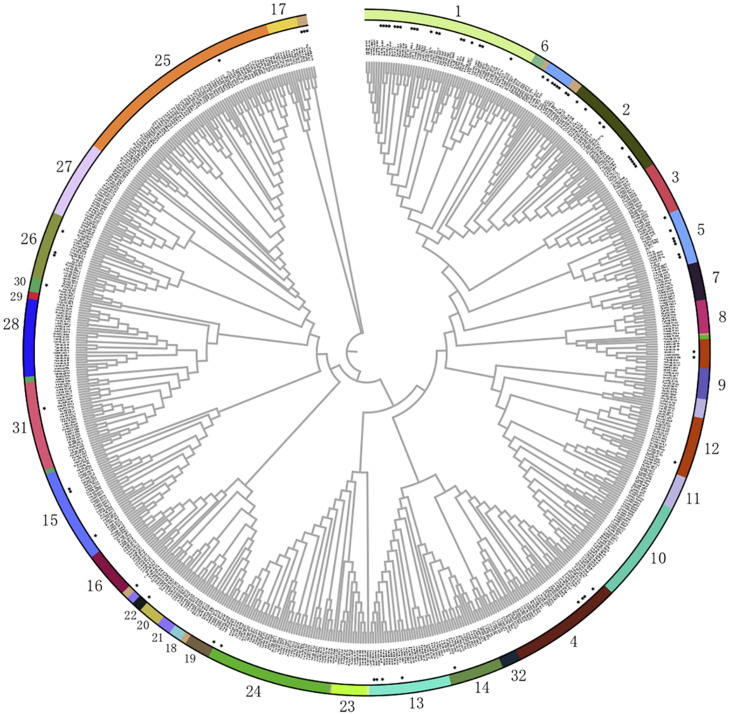

To uncover the potential roles of bHLHs from different subfamilies in various stress responses, most of the functionally annotated bHLH TFs were categorized into the abovementioned 32 subfamilies (Figure 2 and Table 2). The response function of different bHLH subfamilies to abiotic stress is different. We found that nearly half of the bHLHs subfamilies participated in abiotic stress responses. Among them, there are nine subfamilies of bHLHs involved in drought response, including subfamilies 1, 2, 4, 5, 13, 15, 24, 26, and 30, in which most members are from subfamilies 1, 2, and 15. As well, there are nine subfamilies of bHLHs participating in salinity resistance, including subfamilies 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 13, 15, 26, and 27. The majority of salinity responsive bHLHs are from subfamilies 1 and 4. In addition, five subfamilies were found to regulate the cold tolerance of plants, including 1, 2, 13, 15, and 26. Interestingly, members in subfamily 1 were found to be able to take over the regulation of chilling responses. Furthermore, bHLHs of subfamilies 1, 3, 4, 12, 28, and 31 are involved in the response to iron deficiency. In short, bHLHs of subfamily 1 seem to participate in most kinds of abiotic stresses, such as drought, salinity, chilling and iron deficiency. Moreover, members of subfamily 2 mainly participate in drought, salt, and cold stress, while that of subfamily 4 mainly regulates responses to drought, salt, and iron deficiency stress.

FIGURE 2.

Phylogenetic relationships of bHLH family members. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA7.0 with the neighbor-joining method and 1000 bootstrap replicates (Huang and Dai, 2015; Wang et al., 2016b). Then the trees were visualized using iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/). Group names were marked outside the circle. The bHLH protein sequences were downloaded from the JGI (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/) and NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) databases. The Gene and Protein IDs of all these bHLHs are list in Supplementary Tables 1, 2. And the bHLH members that have been functional annotated are labeled with a star marker.

TABLE 2.

bHLH transcription factors involved in plant abiotic stress response.

| Original plant | Stress response | Nomenclature | Subfamily | Target gene | Regulation type | Function | References |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Drought | rd22BP1/AtMYC2/AtbHLH006 | 2 | rd22/P5CS1/AtNHX1 | Positive regulation | Participate in drought stress response | Abe et al., 1997; Chen et al., 2011; Verma et al., 2020 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Drought | AtbHLH112 | 15 | P5CS | Positive regulation | Participate in drought stress response | Liu et al., 2014, 2015 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Drought | AtbHLH68 | 15 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in drought stress response | Le Hir et al., 2017 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Drought/Salt | AtAIB/AtbHLH17 | 2 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in drought and salt stress response | Liu et al., 2014, 2015 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Salt | AtNIG1/AtbHLH028 | 2 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in salt stress response | Kim and Kim, 2006 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Salt | AtbHLH92 | 7 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in salt stress response | Jiang et al., 2009 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Salt | AtbHLH122 | 27 | AtNHX6 | Unknown | Participate in salt stress response | Liu et al., 2014; Krishnamurthy et al., 2019 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Cold | AtICE1/AtbHLH116 | 1 | CBF | Positive regulation | Participate in cold stress response | Chinnusamy et al., 2003 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Iron deficiency | FIT/AtbHLH29 | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in iron deficiency response | Wang et al., 2007, 2013; Yuan et al., 2008; Lingam et al., 2011; Cui et al., 2018 |

| AtbHLH38 | 12 | FRO2, IRT1 | Positive regulation | ||||

| AtbHLH39 | 12 | FRO2, IRT1 | Positive regulation | ||||

| AtbHLH100 | 12 | Unknown | Positive regulation | ||||

| AtbHLH101 | 12 | Unknown | Positive regulation | ||||

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Iron deficiency | AtbHLH18 | 3 | Unknown | Negative regulation | Participate in iron deficiency response | Cui et al., 2018 |

| AtbHLH19 | 3 | Unknown | Negative regulation | ||||

| AtbHLH20 | 3 | Unknown | Negative regulation | ||||

| AtbHLH25 | 3 | Unknown | Negative regulation | ||||

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Iron deficiency | AtbHLH104 | 4 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in iron deficiency response | Li X. et al., 2016; Rohrmann, 2019 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Iron deficiency | AtbHLH34 | 4 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in iron deficiency response | Li X. et al., 2016 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Iron deficiency | AtbHLH121 | 4 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in iron deficiency response | Lei et al., 2020 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Iron deficiency | ILR3/AtbHLH105 | 4 | Unknown | Positive regulation/Negative regulation | Participate in iron deficiency response | Long et al., 2010; Kroh and Pilon, 2019; Tissot et al., 2019 |

| PYE/AtbHLH47 | 4 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in iron deficiency response | |||

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Iron deficiency | AtbHLH115 | 4 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in iron deficiency response | Liang et al., 2017 |

| Oryza sativa L. | Salt | OsbHLH035 | 13 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in salt stress response | Chen et al., 2018 |

| Oryza sativa L. | Salt | OsbHLH062 | 4 | OsHAK21 | Unknown | Participate in salt stress response | Wu et al., 2015 |

| Oryza sativa L. | Salt | OsbHLH068 | 15 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in salt stress response | Huang et al., 2015 |

| Oryza sativa L. | Cold | OsbHLH1 | 1 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in cold stress response | Wang et al., 2003 |

| Oryza sativa L. | Iron deficiency | OsIRO2/OsbHLH056 | 12 | OsNAS1, OsNAS3, OsIRT1, OsFDH, OsAPT1, IDS3 | Positive regulation | Participate in iron deficiency response | Ogo et al., 2006 |

| Oryza sativa L. | Iron deficiency | OsbHLH133 | 28 | Unknown | Negative regulation | Participate in iron deficiency response | Kool et al., 1994 |

| Oryza rufipogon | Salt/Cold | OrbHLH001 | 1 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in salt and cold stress response | Li et al., 2010 |

| Oryza rufipogon | Salt/Osmotic | OrbHLH2 | 1 | DREB1A/CBF3, RD29A, COR15A, KIN1 | Positive regulation | Participate in salt stress and osmotic stress response | Zhou et al., 2009 |

| Populus euphratica | Drought | PebHLH35 | 1 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in drought stress response | Dong et al., 2014 |

| Eleusine coracana L. | Drought/Salt/Oxidative | EcbHLH57 | 4 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in drought, salt stress and oxidative response | Babitha et al., 2015 |

| Zea mays L. | Drought | ZmPTF1 | 26 | NCED, CBF4, ATAF2/NAC081, NAC30 | Positive regulation | Participate in drought stress response | Li Z.X. et al., 2019 |

| Zea mays L. | Drought | ZmPTF3 | 24 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in drought stress response | Gao et al., 2018 |

| Zea mays L. | Heavy metal | ZmbHLH105 | 4 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in heavy metal stress response | Sun et al., 2019 |

| Vitis vinifera | Drought/Salt/Cold | VvbHLH1 | 1 | CBF3, RD29A | Positive regulation | Participate in drought, salt stress and cold response | Wang et al., 2016a |

| Fagopyrum tataricum | Drought/Oxidative | FtbHLH3 | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in drought stress and oxidative response | Yao et al., 2017 |

| Fagopyrum tataricum | Cold | FtbHLH2 | 2 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in cold stress response | Yao et al., 2018 |

| Antirrhinum majus L. | Drought/Salt | AmDEL | 5 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in drought and salt stress response | Wang et al., 2016b |

| Solanum tuberosum | Drought | StbHLH45 | 13 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in drought stress response | Wang et al., 2018 |

| Triticum aestivum L. | Cold | TabHLH1 | 26 | PT, NRT, AEs | Positive regulation | Participate in cold stress and osmotic stress response | Yang et al., 2016 |

| Triticum aestivum L. | Osmotic | TabHLH39 | orphan | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in osmotic stress response | Zhai et al., 2016 |

| Triticum aestivum L. | Salt | TabHLH13 | 4 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in salt stress response | Fu et al., 2014 |

| Solanum lycopersicum | Salt/Osmotic | SlICE1a | 1 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in salt stress and osmotic stress response | Feng et al., 2013 |

| Solanum lycopersicum | Iron deficiency | FER | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in iron deficiency response | Ling et al., 2002 |

| Tamarix hispida Willd. | Salt | ThbHLH1 | 26 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in salt stress response | Ji et al., 2016 |

| Pyrus ussuriensis | Cold | PuICE1 | 1 | PuDREBa | Unknown | Participate in cold stress response | Huang et al., 2015 |

| Pyrus ussuriensis | Cold | PubHLH1 | 1 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in cold stress response | Jin et al., 2016 |

| Raphanus sativus | Cold | RsICE1 | 1 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in cold stress response | Man et al., 2017 |

| Brassica campestris L. | Cold | BcICE1 | 1 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in cold stress response | Zhang et al., 2018 |

| Dimocarpus longan Lour. | Cold | DlICE1 | 1 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in cold stress response | Yang et al., 2019 |

| Nicotiana tabacum L. | Cold | NtbHLH123 | 15 | NtCBF | Positive regulation | Participate in cold stress response | Zhao et al., 2018 |

| Citrus sinensis | Cold | CsbHLH18 | 13 | CsPOD | Positive regulation | Participate in cold stress response | Geng and Liu, 2018 |

| Zoysia japonica | Cold | ZjICE1 | 1 | ZjDREB1 | Positive regulation | Participate in cold stress response | Zuo et al., 2019 |

| Vitis amurensis | Cold | VabHLH1 | 1 | CBF3, RD29A | Positive regulation | Participate in cold stress response | Xu et al., 2014 |

| Glycine Max (L.) Merrill | Iron deficiency | GmbHLH57 | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in iron deficiency response | Li L. et al., 2018 |

| Glycine Max (L.) Merrill | Iron deficiency | GmbHLH300 | 12 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in iron deficiency response | Li L. et al., 2018 |

| Malus × domestica Borkh. | Iron deficiency | MdbHLH104 | 31 | MdAHA8 | Positive regulation | Participate in iron deficiency response | Zhao et al., 2016 |

| Populus tomentosa Carr. | Iron deficiency | PtFIT | 1 | Unknown | Positive regulation | Participate in iron deficiency response | Huang et al., 2015 |

| Chrysanthemum morifolium | Iron deficiency | CmbHLH1 | 4 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in iron deficiency response | Zhao et al., 2014 |

| Hordeum vulgare subsp. vulgare | Iron deficiency | HvIRO2 | 12 | Unknown | Unknown | Participate in iron deficiency response | Ogo et al., 2006 |

bHLHs Involved in Drought Stress

The effects of drought stress on plants are mainly manifested in decreased photosynthesis efficiency, disordered hormone metabolism, and reduced enzyme activities, causing irreversible damage to plant growth and yield (Sun et al., 2018). The bHLH TFs regulate the plant drought-tolerant responses mainly through modulation of the sensitivity to Abscisic acid (ABA) or by regulating the development of stomata, leaf trichome, and root hair (Castilhos et al., 2014). Li et al. (2007) found that the expression of the bHLH-type transcription factor AtAIB was temporarily induced by ABA, and that plants overexpressing AtAIB showed a stronger drought tolerance. Le Hir et al. (2017) found that AtbHLH68 may play a role in responding to drought stress, likely through an ABA-dependent pathway by either directly or indirectly regulating components of ABA signaling and/or metabolism. Yao et al. (2017) demonstrated that heterologous expression of tartary buckwheat FtbHLH3 in Arabidopsis could positively regulate drought/oxidative stress tolerance in an ABA dependent manner. Rao et al. (2020) reported that a large number of bHLHs are involved in ABA signaling and positively regulated stress resistance in Lycium ruthenicum.

In Arabidopsis, AtbHLH006/rd22BP1/AtMYC2 can regulate the expression of RD22. Interestingly, AtbHLH006 can bind to different cis-acting elements under different conditions. AtbHLH006 binds to the E-box (but not G-box) on the PLETHORA gene promoter in JA mediated regulation of the Arabidopsis root stem cell niche (Chen et al., 2011); it could also bind to the G-box motif of the SAG29 promoter to activate its expression during JA mediated leaf senescence (Qi et al., 2015). Another bHLH transcription factor, ZmPTF1 in maize, regulates drought tolerance by promoting root development and the synthesis of ABA (Li Z.X. et al., 2019). Dong et al. (2014) found that plants overexpressing Populus euphratica PebHLH35 had significantly lower stomatal density and decreased stomatal opening than wild-type plants, so their transpiration was significantly reduced. Zhao et al. (2020) illustrated that Apple MdbHLH130 acts as a positive regulator of water stress response by regulating stomatal closure and ROS-scavenging in tobacco.

bHLHs Involved in Salt Stress

High salt stress caused by ionic and osmotic stressors eventually results in the suppression of plant growth and a reduction in crop productivity. Some bHLH TFs have a regulatory effect under saline conditions. Under salt stress, plant cells successively face the challenges of osmotic stress, ion toxicity, and oxidative stress (Rozema and Flowers, 2008). As discussed previously, bHLH TFs usually enhance a plant’s resistances to these secondary stresses. AtNIG1 in Arabidopsis was the first bHLH transcription factor shown to be involved salt stress signaling pathways from plants. The survival rate and dry weight of the atnig1 mutant decreased significantly under salt stress (Kim and Kim, 2006). Fu et al. (2014) showed that the expression level of the wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) TabHLH13 gene was significantly up-regulated with the increase of salt ion concentration in the environment. Wu et al. (2015) showed that OsbHLH062 could regulate ion transport genes, such as OsHAK21, and modulate the Jasmonic acid (JA) signaling pathway, so as to endow plants with some resistance to salt stress. One of the most important mechanisms by which bHLH TFs participate in salt tolerance is to regulate ROS balance by directly regulating the expression of a group of peroxidase genes. Jiang et al. (2009) found that AtbHLH92 elevated Arabidopsis tolerance to salt and osmotic stresses through a partial dependence on ABA and SOS2. The beet homolog of AtbHLH92, BvbHLH92, was found to be expressed in both the beet root and leaf in response to salt stress (Jiang et al., 2009). In Tamarix hispida, ThbHLH1 was highly expressed under high salt induction, significantly increasing peroxidase (POD) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activities (Ji et al., 2016). AtbHLH112 increased the expression of the POD and SOD genes, while concomitantly reduced the expression of the P5CDH and ProDH genes, so as to enhance the resistance of Arabidopsis to high salt (Liu et al., 2014). In addition, bHLHs could also regulate the accumulations of resistance-related secondary metabolites in order to improve plant salinity tolerance. Verma et al. (2020) found that salt stress activated AtMYC2 through a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade. Then, the AtMYC2 could bind to the promotor of rate-limiting enzyme P5CS1 in the biosynthesis of proline, thereby regulating the biosynthesis of proline, and thus regulating salt tolerance. AtbHLH122 inhibited the expression of CYP707A3 gene under NaCl stress (Liu et al., 2014). Furthermore, Krishnamurthy et al. (2019) identified AtMYC2 and AtbHLH122 as upstream regulators of the ABA-mediated AtNHX1 and AtNHX6, which are both Na+/H+ exchangers, by chromatin immunoprecipitation. Moreover, overexpression of EcbHLH57 can enhance the resistance of tobacco to salt stress by elevating the expression of stress responsive genes such as LEA14, rd29A, rd29B, SOD, APX, ADH1, HSP70, and also PP2C (Babitha et al., 2015). OsbHLH068 has a similar effect as AtbHLH112 in regulating the salt stress response. In Arabidopsis, heterogenic overexpression of OsbHLH068 can reduce salt-induced accumulation of H2O2 (Chen et al., 2017).

bHLHs Adjust Plants to Low Temperature Stress

Cold stress is a severe threat for plant productivity and crop production, particularly so when it occurs during the growth phase (Albertos et al., 2019). The DREB1/CBF (dehydration-responsive element binding/C-repeat binding factors) gene is considered as the main regulator of plant’s cold stress response. Under low temperature stress, OsDREBL and OsTPP1 genes were significantly up-regulated at the transcriptional level after overexpression of RsICE1 (inducer of CBF expression) in rice, indicating that RsICE1 is involved in the DREB1/CBF cold regulation signaling network (Man et al., 2017). In Arabidopsis the AtICE1/AtbHLH116 protein binds to the CBF promoter region at low temperatures to affect transcription initiation, and AtICE1/AtbHLH116 overexpressing plants showed higher tolerance to cold (Chinnusamy et al., 2003). The bHLH transcription factor DlICE1 from Dimocarpus longan Lour has a positive regulatory effect on cold tolerance. Overexpression of DlICE1 in Arabidopsis conferred enhanced cold tolerance via increased proline content, decreased ion leakage, and reduced malondialdehyde (MDA) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation. The expressions of the ICE1-CBF cold signaling pathway genes, including AtCBF1/2/3 and cold-responsive genes (AtRD29A, AtCOR15A, AtCOR47, and AtKIN1), were also significantly higher in DlICE1-overexpressing lines than in wild-type (WT) plants under cold stress (Yang et al., 2019). ICE1 proteins in other plants have similar functions. PuICE1 of can elevate the transcriptional expression of PuDREBa by interacting with PuHHP1, thus improving the cold resistance of Pyrus ussuriensis (Huang et al., 2015). The overexpression of BcICE1 in tobacco can positively regulate the expression of stress-related genes such as CBFs (C-repeat binding factor) and enhance the antioxidant activity and osmotic ability of plants (Zhang et al., 2018). Zuo et al. (2019) showed that the transgenic Arabidopsis with overexpressed Zoysia japonica ZjICE1 showed an enhanced tolerance to cold stress with an increase in SOD, POD, as well as higher free proline content and decreased MDA content. They also upregulated the transcript abundance of cold-responsive genes (CBF1, CBF2, CBF3, COR47A, KIN1, and RD29A). ZjICE2 from Zoysia japonica enhanced the tolerance of transgenic plants to cold stress by activating DREB/CBF regulators and enhancing reactive oxygen species scavenging (Zuo et al., 2019). In addition to ICE proteins, some bHLH proteins are also responsible for plant resistance to low temperatures. As a homolog of ICE1, the rice OrbHLH001 could enhance the tolerance of transgenic Arabidopsis to freezing stress. However, the function of OrbHLH001 was different from that of ICE1 and is independent of a CBF/DREB1 cold-response pathway (Li et al., 2010). The grape VvbHLH1 and VabHLH1 are positive regulators of the cold stress response, and the overexpression of these two genes could enhance the expression level of the COR gene (Xu et al., 2014). The apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) MdCIbHLH1 gene was recently identified as a hub in the transcriptional regulation of bark freezing tolerance Liang et al. (2020). Moreover, Zhao et al. (2018) demonstrated that NtbHLH123 is a transcriptional activator that plays a positive regulatory role in cold tolerance by activating the reactive oxygen species scavenging-related gene NtCBF. Geng and Liu (2018) found that CsbHLH18 can regulate ROS homeostasis at least partially by directly regulating the antioxidant gene CsPOD, thus playing an active role in cold tolerance.

bHLHs Enhances Plant Survival in Heavy Metal Toxicity

Excessive heavy metals in agricultural lands cause declines in crop productivity (Thao et al., 2015). Song et al. (2014) found that excessive expression of GmbHLH30 in tobacco can enhance its resistance to aluminum toxicity through the maintenance of osmotic pressure. Manganese (Mn) toxicity is also an important factor for limiting crop production in acidic soils. Sun et al. (2019) found that ZmbHLH105 may improve maize tolerance to Mn stress by regulating antioxidant mechanism-mediated ROS clearance and the expression of Mn/Fe-related transporters in plants.

bHLHs Help Withstand Plant Iron and Copper Homeostasis

The key bHLH transcription factor in iron (Fe) uptake, FER-LIKE IRON DEFICIENCY-INDUCED TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR (FIT), is critical for adjusting Fe acquisition to plant growth and environmental constraints (Gratz et al., 2020). Kool et al. (1994) found that the bHLH133 transcription factor in rice can regulate the transport of Fe from roots to young leaves, revealing the important role of bHLH proteins in maintaining iron homeostasis in plant cells. Ling et al. (2002) found that the bHLH transcription factor FER from tomato played a role in the regulation of plant root iron nutrition. Yuan et al. (2008) found that the FIT/bHLH29 (FER-like iron deficiency-induced transcription factor) gene played an important role in maintaining intracellular Fe balance through regulating the expression of downstream iron absorption genes. The plant hormone ethylene is one of the signals that trigger iron deficiency responses at both the transcriptional level and the post-transcriptional level. Through ethylene signal transduction, the FIT/bHLH29 protein is protected from degradation by proteasomes (Lingam et al., 2011). Increased FIT levels subsequently leads to the high level of expression of genes required for Fe acquisition. Cui et al. (2018) found that the bHLH18, bHLH19, bHLH20, and bHLH25 in the Iva subgroup are FIT/bHLH29 interactors, which can promote JA induced FIT/bHLH29 protein degradation. Previously, Wang et al. (2017, 2019) demonstrated that four Ib bHLH genes (AtbHLH38, AtbHLH39, AtbHLH100, and AtbHLH101) played important roles in the iron-deficiency responses, though they are not induced by FIT/bHLH29 under iron deficiency conditions. Actually, these four Iva bHLHs mainly antagonized Ib bHLHs, so as to regulate the stability of the FIT/bHLH29 protein under iron deficiency conditions. Furthermore, Lei et al. (2020) found that bHLH121 interplayed with another bHLH transcription factor in the Ivc subgroup to positively regulate FIT/bHLH29 expression, thus playing a key role in maintaining Fe homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Zhang et al. (2015) identified the Arabidopsis AtbHLH104 as a member in subfamily Ivc and demonstrated that bHLH104 acted as a key component positively regulating Fe deficiency responses via targeting Ib subgroup bHLH genes and PYE/bHLH47 expression. Li X. et al. (2016) supplemented this study and proposed that bHLH34, bHLH104, and bHLH105 (IAA-LEUCINE RESISTANT3) can be used as homologous dimers or heterodimers to regulate the stable state of Fe without redundancy. ILR3/bHLH105, alone was shown to stimulate Fe uptake by inhibiting ferritin expression (Kroh and Pilon, 2019; Tissot et al., 2019). Long et al. (2010) showed through chromatin immunoprecipitation-on-chip analysis and transcriptional profiling that PYE/bHLH47 helped maintain iron homeostasis by regulating the expression of known iron homeostasis genes. In addition, AtbHLH115 is also a positive regulator of iron deficiency responses, being negatively regulated by the E3 ligase BTS (Liang et al., 2017). In poplar, transgenic line (TL2) overexpressing PtFIT showed a higher chlorophyll content and Chl a/b ratio than the control plant under the conditions of iron deficiency, indicating that PtFIT was involved in the iron deficiency reaction (Zhai et al., 2018). Ogo et al. (2006) found that overexpression of OsIRO2/OsbHLH056 could promote the absorption of iron in rice. Zhao et al. (2014) demonstrated that Chrysanthemum CmbHLH1 promoted iron absorption through H+-ATPase mediated rhizosphere acidification. Recent research demonstrated that the overexpression of GmbHLH57 and GmbHLH300 up-regulated the iron absorption genes and increased the iron content of transgenic soybean plants (Li L. et al., 2018). Moreover, overexpression of NtbHLH1 results in longer roots, altered rhizosphere pH, and increased ferric-chelate reductase activity under iron deficient conditions (Li et al., 2020). Wang et al. (2020) characterized the role of a novel rice bHLH type transcription factor OsbHLH156 in Fe homeostasis and found that OsbHLH156 is mainly expressed in roots and transcription is greatly increased by iron deficiency. Loss of function of OsbHLH156 resulted in Fe-deficiency-induced chlorosis and reduced Fe concentration in the shoots under upland or Fe(III) supplied conditions.

Plants must maintain the homeostasis of Fe and Cu. When plants are under Fe-deficiency conditions, bHLH IVC not only directly activates bHLH Ib expression but also promotes bHLH Ib and FIT gene expression through interaction with bHLH121. FIT and bHLH Ib members initiate transcription of Fe-uptake genes (IRT1 and FRO2) and Cu-uptake genes (COPT2, FRO4, and FRO5). An increase in Cu concentration alleviates Fe-deficiency stress. Under Cu-deficiency, Cu-uptake genes (COPT2, FRO4, and FRO5) are activated in response to SPL7. CITF1 also regulates the expression of COPT2, FRO4, and FRO5. SPL7 not only regulated the Cu homeostasis signaling pathway, but also suppressed (IPON MANs) IMAS and bHLH Ib of the Fe homeostasis signaling pathway (Cai et al., 2021).

bHLHs Involved in Osmotic Stress

Proper osmoregulation is important for plant response to environmental changes (Lin et al., 2020). Drought, high salinity, low temperature, and other conditions will affect the water content of plants, thus leading to osmotic stress. Therefore, osmotic stress is often accompanied by other types of environmental stresses. Under osmotic stress, RD29A can be regulated through both ABA-independent and ABA-dependent pathways, thus improving plant stress resistance (Yang et al., 2016). Zhai et al. (2016) found that the expression level of RD29A was upregulated in transgenic plants overexpressing TabHLH39. The overexpression of the wild rice gene OrbHLH2 (a homolog protein of ICE1) in Arabidopsis up-regulates the expression of stress response genes DREB1A/CBF3, RD29A, COR15A, and KIN1, thus enhancing tolerance to osmotic stress (Zhou et al., 2009). A MYC-type ICE1-like transcription factor SlICE1a in tomatoes was induced in response to osmotic stress (Feng et al., 2013).

bHLHs Regulate Plant Flavonoids Synthesis in Response to Abiotic Stress

In vegetative tissues, the flavonoid pathway is usually induced in response to physiological and environmental fluctuations as a protective mechanism against oxidative stresses induced by pathogen infections, high-light, UV, extreme temperature, drought, salt, and deficiency of N, P, or C nutrition (Xu et al., 2015). The bHLH transcription factor family is important for regulating the biosynthetic pathway of flavonoids (Hichri et al., 2011). Flavonoids are generally divided into six categories: flavone, flavonol, isoflavone, flavanone, flavanol, and anthocyanidin (Hichri et al., 2011). In Ludwig et al. (1989) the Lc protein was initially isolated from maize and showed transcriptional activity on genes involved in anthocyanin synthesis. Heterologous overexpression of the Lc gene significantly enhanced the accumulation of flavonoids in mature fruits of cherry tomato (Bovy et al., 2002). Since then, the vital roles of bHLH in flavonoid synthesis have attracted growing attention. Flavonoids have strong biological activity and significant antioxidant capacity (Mitchell et al., 1998; Xu et al., 2015), and they play protective roles when plants are subjected to single or multiple stresses such as ultraviolet radiation, salt, temperature, and drought. The level of protection is determined by the position of free hydroxyl groups in the structure of flavonoids and the carbon-carbon double bond in the C ring.

To reveal the relationship between bHLH subfamilies and flavonoid biosynthesis, all the functional annotated bHLHs were categorized into the 32 known subgroups in this research (Figure 2 and Table 3). It seems that only bHLHs in subfamilies 1, 2, 5, 13, 14, 15 are involved in the regulation of flavonoid metabolism (Table 3). Among them, more than half of the annotated bHLHs involved in flavonoid metabolism regulation come from subfamilies 2 and 5. As flavonoids are important metabolites involved in plant responses to abiotic stresses, bHLHs of subfamilies 2 and 5 may regulate a series of physiological stress responses. The typical bHLH transcription factor in the IIIf subfamily [equivalent to the subfamily 5] AtTT8/AtbHLH042 can regulate the expression of DFR and BAN, two flavonoid late biosynthetic genes, thus affecting the synthesis of anthocyanins and procyanidins (Nesi et al., 2000). AtTT8/AtbHLH042 constitutes a major regulatory step in the specific activation of the expression of flavonoid structural genes (Baudry et al., 2006). Similarly, MtTT8 in Medicago truncatula is considered to be the central component of a ternary complex (MYB-bHLH-WD40) that controls the biosynthesis of anthocyanins and procyanidins (Li P. et al., 2016). In addition to AtTT8, three other bHLH genes are also categorized into the IIIf clade: AtGL3, AtEGL3, and AtMYC1. They are also known to be involved in biosynthesis of flavonoids (Maes et al., 2008; Symonds et al., 2011). Together with MYB factors, especially PAP2 (AtMYB90), GL3 seems to be a partner of bHLHs in anthocyanin accumulation under nitrogen-deficient conditions (Lea et al., 2007). In contrast, nightshade GLABRA3 (SlGL3), the homolog to AtGL3, inhibited anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis (Tominaga-Wada et al., 2018).

TABLE 3.

Regulation of bHLH transcription factors on metabolism of flavonoids.

| Species | Nomenclature | Subfamily | Target gene | Function | References |

| Zea mays L. | Lc | 5 | Unknown | Synthetic anthocyanin | Ludwig et al., 1989; Bovy et al., 2002 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | AtTT8/AtbHLH042 | 5 | DFR/BAN | Regulate the expression of DFR and BAN, Synthetic anthocyanin and procyanidine | Nesi et al., 2000; Baudry et al., 2006 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | AtGL3/AtbHLH001 | 5 | E2F | Participate in the biosynthesis of flavonoids | Lea et al., 2007; Maes et al., 2008; Symonds et al., 2011 |

| AtEGL3/AtbHLH002 | 5 | Unknown | |||

| AtMYC1/AtbHLH012 | 5 | Unknown | |||

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | AtMYC3/AtbHLH005 | 2 | JAZ1, JAZ3, JAZ9 | Synthetic anthocyanin | Niu et al., 2011 |

| AtMYC4/AtbHLH004 | 2 | JAZ1, JAZ3, JAZ9 | |||

| Vitis vinifera L. | VvbHLH1 | 1 | CBF3, RD29A | Regulate the expression of the key enzyme genes (CHS, F3H, DFR and LDOX) | Wang et al., 2016a |

| Vitis vinifera L. | VvbHLH003 | 13 | Unknown | Synthetic anthocyanin | Wang et al., 2018 |

| Vitis vinifera L. | VvbHLH007 | 2 | Unknown | Synthetic flavone | Wang et al., 2018 |

| Vitis vinifera L. | VvMYC1 | 5 | Unknown | Regulate the expression of the key enzyme genes (CHI, UFGT, ANR), synthetic anthocyanin and tannin when co-expressed with VvMYB | Hichri et al., 2010 |

| Medicago truncatula | MtTT8 | 5 | Unknown | Control anthocyanin and procyanidine biosynthesis | Li P. et al., 2016 |

| Solanum lycopersicum | SlAN1 | 5 | Unknown | Associated with anthocyanins | Li N. et al., 2018 |

| Solanum lycopersicum | SlGL3 | 5 | Unknown | Inhibit anthocyanin accumulation | Tominaga-Wada et al., 2018 |

| Antirrhinum majus L. | AmDEL | 5 | Unknown | Induce anthocyanins | Outchkourov et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016b |

| Setaria italica | PPLS1 | 5 | Unknown | Regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis | Bai et al., 2020 |

| Malus domesica Borkh. | MdbHLH33 | 15 | Unknown | Control anthocyanin biosynthesis | Xu et al., 2017 |

| Malus domesica Borkh. | MdMYC2 | 2 | JAZ3 | Control anthocyanin biosynthesis | An et al., 2016 |

| Malus domesica Borkh. | MdbHLH74 | 14 | Unknown | inhibit anthocyanin accumulation | Li W.F. et al., 2019 |

| Fragaria ananassa Duch. | FabHLH25 | 2 | Unknown | Synthetic anthocyanin | Zhao et al., 2018 |

| FabHLH29 | 5 | ||||

| FabHLH80 | 2 | ||||

| FabHLH98 | 5 | ||||

| Triticum aestivum L. | TaMYC1 | 5 | Unknown | Activate transcription of the anthocyanin biosynthesis structural genes | Shoeva, 2018 |

| Triticum aestivum L. | TaPpb1 | 5 | Unknown | Regulate anthocyanin synthesis when co-expressed with TaPpm1 | Jiang et al., 2018 |

| Anthurium andraeanum Linden | AabHLH1 | 5 | Unknown | Regulate the accumulation of procyanidins when co-expressed with AaMYB3 | Li L. et al., 2019 |

| Prunus persica | PpbHLH3 | 1 | Unknown | Form complexes that then regulate the synthesis of anthocyanins | Ravaglia et al., 2013 |

| Solanum melongena L. | SmbHLH13 | 15 | SmCHS/SmF3H | Control anthocyanin biosynthesis | Babitha et al., 2015 |

| Chimonanthus praecox (Linn.) Link | CpbHLH13 | 2 | Unknown | Reduce the anthocyanin contents | Aslam et al., 2020 |

| Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat. | CmbHLH2 | 5 | CmDFR | Upregulate the CmDFR promoter and triggered anthocyanin accumulation when co-expressed with CmMYB6 | Xiang et al., 2015 |

| Actinidia chinensis Planch | AcbHLH42 | orphan | AcF3GT1/AcANS | Synthetic anthocyanin when co-expressed with AcMYB123 | Wang et al., 2019 |

| Plagiochasma appendiculatum | PabHLH1 | 5 | Unknown | Activate the synthesis of flavonoids and anthocyanins | Zhao et al., 2019 |

| Dendrobium hybrids | DhbHLH1 | 5 | Unknown | Regulate anthocyanin production | Li et al., 2017 |

Homologous or heterologous overexpression of bHLHs can exhibit a significant regulatory effect on the synthesis of various flavonoids. Actually, most bHLH have been found to possess a positive regulatory function on plant flavonoid synthesis. In Arabidopsis, transgenic plants overexpressing AtMYC3 and AtMYC4 showed higher levels of anthocyanin than that of wild-type plants (Niu et al., 2011). Heterologous overexpression of the grape VvbHLH1 gene increases the activity of key enzymes in the flavonoid synthesis pathway such as Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase (PAL), Chalcone Synthase (CHS), Chalcone Isomerase (CHI), and Flavanone-3-Hydroxylase (F3H) as well as enhancing the salt and drought tolerance of transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings (2016a). VvbHLH003 and VvbHLH007 were also found to be related to anthocyanin or flavonoids synthesis (Wang et al., 2018). Likewise, the heterologous expression of eggplant (Solanum melongena) SmbHLH13 can promote anthocyanin biosynthesis by positively regulating the expression of the structural genes SmCHS and SmF3H. The heterologous expression of Arabidopsis PAP2 induces anthocyanin accumulation in tomato (Li N. et al., 2018), while the heterogeneous overexpression of liverwort (Plagiochasma appendiculatum) PabHLH1 in Arabidopsis can activate the synthesis of both flavonoids and anthocyanins, through the up-regulation of early and late structural genes in the synthesis pathway of flavonoids (Zhao et al., 2019). The ectopic overexpression of apple MdMYC2 also significantly up-regulated the transcriptional expression of these structural genes in transgenic Arabidopsis lines (An et al., 2016). Recent studies have shown that both triticale (Triticum × Secale) TsMYC2 and wheat (Triticum aestivum) TaMYC1 can regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis and control the grain properties (Zong et al., 2019). On the other hand, several bHLHs could negatively regulate flavonoid synthesis. For example, the wintersweet (Chimonanthus praecox L.) CpbHLH13 was found to reduce the anthocyanin content when ectopically overexpressed in the tobacco inflorescence (Aslam et al., 2020).

It is generally believed that the mechanism of action of flavonoids in the stress-resistance process is through their antioxidant properties. Under abiotic stresses, such as low temperature, drought, high salt, or heavy metal exposure, a series of physiological and biochemical changes will occur in plant cells, which are mainly manifested as the reduction of photosynthesis efficiency and the generation of a large number of reactive oxygen radicals, as well as serious damage to cell structure (Winkel-Shirley, 2001). The oxidative stress generated by these reactive oxygen species can also induce a large amount of flavonoids synthesis, thereby quenching the reactive oxygen species and protecting cells from oxidative damage (Treutter, 2006). Qin et al. (2021) found that abiotic stress promotes the synthesis of anthocyanins by inhibiting SPL9 through miR156, thereby facilitating the neutralization of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and simultaneously inducing ZmSRO1e. ZmSRO1e interacts with ZmPL1/AtPAP1 to inhibit the formation of an activated MBW complex, thus repressing the over-accumulation of anthocyanins under abiotic stress. These two pathways balance the relationship between development and abiotic stress tolerance via their control of ROS accumulation. Overexpression of the Antirrhinum majus bHLH gene AmDEL led to the up-regulation of genes related to the biosynthesis of flavonoids, proline biosynthesis, and reactive oxygen scavenging under both salt and drought stress (Wang et al., 2016b). Moreover, flavonoids can also bind with copper irons to reduce the toxic damage of these ions to cytoplasmic structures and organelles such as chloroplasts (Rice-Evans et al., 1996). The role of flavonoids in plant stress tolerance is not only limited to the removal of reactive oxygen species, but also can act as signaling molecules (Ribeiro et al., 2015).

Concluion

As one of the most numerous TFs in eukaryotes, the bHLH family has many members and diverse functions. Many studies have shown that bHLHs can regulate plant resistances to various abiotic stresses (Babitha et al., 2015; Huang and Dai, 2015; An et al., 2016; Jin et al., 2016). As well, there are many reports that show that flavonoids in plants are synthesized in large quantities to effectively eliminate ROS, to enhance the plant’s tolerances to survive in an adverse environment. This naturally leads to an interesting question: Can bHLHs regulate plant tolerance by regulating the synthesis of flavonoids? A large number of studies have confirmed that bHLHs are involved in the synthesis of flavonoids. Specially, bHLHs in subfamily 1, 2, 13, and 15 could bind to G-box or E-box in the promoter of cold, drought, and salinity responsive genes (Tables 1, 2); members of this subfamily also could modulate the synthesis of some flavonoids (Table 3). Since members of this group share similarly conversed protein motifs (Supplementary Figure 1), it is reasonable to hypothesize that plant bHLHs in subfamily 1, 2, 13, and 15 could bind to G-box or E-box of cold, drought and salt responsive genes to further regulate the synthesis of flavonoids. Similarly, it also makes sense that bHLHs in subfamily 5 could regulate the synthesis of flavonoids to resist salinity and drought stresses (Tables 1-3). However, these hypotheses still need to be verified.

Author Contributions

YQ, TZ, YY, JY, JX, and LG analyzed the phylogenetic relationships of bHLH family members. EP conceived the original idea for the review. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the grants 31970286 and 31301053 from the National Science Foundation of China, LY17C020004 from the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, and 20170432B01 from the Hangzhou Science and Technology Bureau.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.677611/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abe H., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Urao T., Iwasaki T., Hosokawa D., Shinozaki K. (1997). Role of arabidopsis MYC and MYB homologs in drought- and abscisic acid-regulated gene expression. Plant Cell 9 1859–1868. 10.1105/tpc.9.10.18591997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A., Niwa Y., Goto S., Ogawa T., Shimizu M., Suzuki A., et al. (2015). bHLH106 Integrates Functions of Multiple Genes through Their G-Box to Confer Salt Tolerance on Arabidopsis. PLoS One 10:e0126872. 10.1371/journal.pone.0126872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertos P., Wagner K., Poppenberger B. (2019). Cold stress signalling in female reproductive tissues. Plant Cell Environ. 42 846–853. 10.1111/pce.13408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An J. P., Li H. H., Song L. Q., Su L., Liu X., You C. X., et al. (2016). The molecular cloning and functional characterization of MdMYC2, a bHLH transcription factor in apple. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 108 24–31. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An X. H., Tian Y., Chen K. Q., Wang X. F., Hao Y. J. (2012). The apple WD40 protein MdTTG1 interacts with bHLH but not MYB proteins to regulate anthocyanin accumulation. J. Plant Physiol. 169 710–717. 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam M. Z., Lin X., Li X., Yang N., Chen L. (2020). Molecular Cloning and Functional Characterization of CpMYC2 and CpBHLH13 Transcription Factors from Wintersweet (Chimonanthus praecox L.). Plants 9:785. 10.3390/plants9060785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchley W. R., Fitch W. M. (1997). A natural classification of the basic helix-loop-helix class of transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94 5172–5176. 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchley W. R., Terhalle W., Dress A. (1999). Positional dependence, cliques, and predictive motifs in the bHLH protein domain. J. Mol. Evol. 48 501–516. 10.1007/PL00006494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babitha K. C., Vemanna R. S., Nataraja K. N., Udayakumar M. (2015). Overexpression of EcbHLH57 Transcription Factor from Eleusine coracana L. in Tobacco Confers Tolerance to Salt, Oxidative and Drought Stress. PLoS One 10:e0137098. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai H., Song Z. J., Zhang Y., Li Z. Y., Wang Y. F., Liu X. (2020). The bHLH transcription factor PPLS1 regulates the color of pulvinus and leaf sheath in foxtail millet (Setaria italica). Theor. Appl. Gene. 133 1911–1926. 10.1007/s00122-020-03566-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry A., Caboche M., Lepiniec L. (2006). TT8 controls its own expression in a feedback regulation involving TTG1 and homologous MYB and bHLH factors, allowing a strong and cell-specific accumulation of flavonoids in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 46 768–779. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02733.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry A., Heim M. A., Dubreucq B., Caboche M., Weisshaar B., Lepiniec L. (2004). TT2, TT8, and TTG1 synergistically specify the expression of BANYULS and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 39 366–380. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02138.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian C., Guo X. Y., Zhang Y., Wang L., Xu T. D., Delong A., et al. (2020). Protein phosphatase 2A promotes stomatal development by stabilizing SPEECHLESS in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117 13127–13137. 10.1073/pnas.1912075117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovy A., De Vos R., Kemper M., Schijlen E., Almenar Pertejo M., Muir S. (2002). High-flavonol tomatoes resulting from the heterologous expression of the maize transcription factor genes LC and C1. Plant Cell 14 2509–2526. 10.1105/tpc.004218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Li Y., Liang G. (2021). FIT and bHLH Ib transcription factors modulate iron and copper crosstalk in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 44 1679–1691. 10.1111/pce.14000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carretero-Paulet L., Galstyan A., Roig-Villanova I., Martinez-Garcia J. F., Bilbao-Castro J. R., Robertson D. L. (2010). Genome-wide classification and evolutionary analysis of the bHLH family of transcription factors in Arabidopsis, poplar, rice, moss, and algae. Plant Physiol. 153 1398–1412. 10.1104/pp.110.153593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castilhos G., Lazzarotto F., Spagnolo-Fonini L., Bodanese-Zanettini M. H., Margis-Pinheiro M. (2014). Possible roles of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors in adaptation to drought. Plant Sci. 223 1–7. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty M., Gangappa S. N., Maurya J. P., Sethi V., Srivastava A. K., Singh A. (2019). Functional interrelation of MYC2 and HY5 plays an important role in Arabidopsis seedling development. Plant J. 99 1080–1097. 10.1111/tpj.14381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. C., Cheng W. H., Hong C. Y., Chang Y. S., Chang M. C. (2018). The transcription factor OsbHLH035 mediates seed germination and enables seedling recovery from salt stress through ABA-dependent and ABA-independent pathways, respectively. Rice 11:50. 10.1186/s12284-018-0244-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. C., Hsieh-Feng V., Liao P. C., Cheng W. H., Liu L. Y., Yang Y. W. (2017). The function of OsbHLH068 is partially redundant with its homolog, AtbHLH112, in the regulation of the salt stress response but has opposite functions to control flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 94 531–548. 10.1007/s11103-017-0624-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Sun J., Zhai Q., Zhou W., Qi L., Xu L. (2011). The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor MYC2 directly represses PLETHORA expression during jasmonate-mediated modulation of the root stem cell niche in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23 3335–3352. 10.1105/tpc.111.089870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T., Zhao P., Ren Y., Zou J., Sun M. X. (2021). AtMIF1 increases seed oil content by attenuating GL2 inhibition. New Phytol. 229 2152–2162. 10.1111/nph.17016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy V., Ohta M., Kanrar S., Lee B. H., Hong X., Agarwal M. (2003). ICE1: a regulator of cold-induced transcriptome and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Genes. Dev. 17 1043–1054. 10.1101/gad.1077503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro A. M., Figueiredo D. D., Tepperman J., Borba A. R., Lourenco T., Abreu I. A. (2016). Rice phytochrome-interacting factor protein OsPIF14 represses OsDREB1B gene expression through an extended N-box and interacts preferentially with the active form of phytochrome B. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 1859 393–404. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Chen C. L., Cui M., Zhou W. J., Wu H. L., Ling H. Q. (2018). Four IVa bHLH Transcription Factors Are Novel Interactors of FIT and Mediate JA Inhibition of Iron Uptake in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 11 1166–1183. 10.1016/j.molp.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon R. A., Xie D. Y., Sharma S. B. (2005). Proanthocyanidins–a final frontier in flavonoid research? New Phytol. 165 9–28. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01217.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y., Wang C. P., Han X., Tang S., Liu S., Xia X. L. (2014). A novel bHLH transcription factor PebHLH35 from Populus euphratica confers drought tolerance through regulating stomatal development, photosynthesis and growth in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 450 453–458. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.05.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubos C., Le Gourrierec J., Baudry A., Huep G., Lanet E., Debeaujon I. (2008). MYBL2 is a new regulator of flavonoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 55 940–953. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03564.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeilpour A., Van Labeke M. C., Samson R., Van Damme P. (2015). Osmotic stress affects physiological responses and growth characteristics of three pistachio cultivars. Acta Physiol. Plant. 37:123. 10.1007/s11738-015-1876-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild C. D., Schumaker M. A., Quail P. H. (2000). HFR1 encodes an atypical bHLH protein that acts in phytochrome A signal transduction. Genes Dev. 14 2377–2391. 10.1101/gad.828000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H. L., Ma N. N., Meng X., Zhang S., Wang J. R., Chai S. (2013). A novel tomato MYC-type ICE1-like transcription factor, SlICE1a, confers cold, osmotic and salt tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 73 309–320. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S. L., Liu G. X., Zhang L. C., Xia C., Zhao G. Y., Jia J. Z., et al. (2014). Cloning and Analysis of a Salt Stress Related Gene TabHLH13 in Wheat. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 15 1006–1011. 10.13430/j.cnki.jpgr.2014.05.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C., Sun J., Wang C., Dong Y., Xiao S., Wang X., et al. (2017). Genome-wide analysis of basic/helix-loop-helix gene family in peanut and assessment of its roles in pod development. PLoS One 12:e0181843. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L. H., Liu B. X., Li J. B., Wu Y. M., Tang Y. X. (2016). Cloning and function analysis of bHLH transcription factor gene GhMYC4 from Gossypium hirsutism L. Chin. Acad. Agricult. Sci. 18 33–41. 10.13304/j.nykjdb.2015.729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Wu M., Zhang M., Jiang W., Liang E., Zhang D. (2018). Roles of a maize phytochrome-interacting factors protein ZmPIF3 in regulation of drought stress responses by controlling stomatal closure in transgenic rice without yield penalty. Plant Mol. Biol. 97 311–323. 10.1007/s11103-018-0739-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z. Y., Sun W. J., Wang J., Zhao C. Y., Zuo K. J. (2019). GhbHLH18 negatively regulates fiber strength and length by enhancing lignin biosynthesis in cotton fibers. Plant Sci. 286 7–16. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng J., Liu J. H. (2018). The transcription factor CsbHLH18 of sweet orange functions in modulation of cold tolerance and homeostasis of reactive oxygen species by regulating the antioxidant gene. J. Exp. Bot. 69 2677–2692. 10.1093/jxb/ery065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz R., Brumbarova T., Ivanov R., Trofimov K., Tunnermann L., Ochoa-Fernandez R. (2020). Phospho-mutant activity assays provide evidence for alternative phospho-regulation pathways of the transcription factor FER-LIKE IRON DEFICIENCY-INDUCED TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR. New Phytol. 225 250–267. 10.1111/nph.16168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz R., Manishankar P., Ivanov R., Koster P., Mohr I., Trofimov K. (2019). CIPK11-Dependent Phosphorylation Modulates FIT Activity to Promote Arabidopsis Iron Acquisition in Response to Calcium Signaling. Dev. Cell 48 726–740. 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim M. A., Jakoby M., Werber M., Martin C., Weisshaar B., Bailey P. C. (2003). The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family in plants: a genome-wide study of protein structure and functional diversity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20 735–747. 10.1093/molbev/msg088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hichri I., Barrieu F., Bogs J., Kappel C., Delrot S., Lauvergeat V. (2011). Recent advances in the transcriptional regulation of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 62 2465–2483. 10.1093/jxb/erq442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hichri I., Heppel S. C., Pillet J., Leon C., Czemmel S., Delrot S. (2010). The Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Transcription Factor MYC1 Is Involved in the Regulation of the Flavonoid Biosynthesis Pathway in Grapevine. Mol. Plant 3 509–523. 10.1093/mp/ssp118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D. Q., Dai W. H. (2015). Molecular characterization of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) genes that are differentially expressed and induced by iron deficiency in Populus. Plant Cell Rep. 34 1211–1224. 10.1007/s00299-015-1779-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Li K., Jin C., Zhang S. (2015). ICE1 of Pyrus ussuriensis functions in cold tolerance by enhancing PuDREBa transcriptional levels through interacting with PuHHP1. Sci. Rep. 5:17620. 10.1038/srep17620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. S., Wang W., Zhang Q., Liu J. H. (2013). A basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, PtrbHLH, of Poncirus trifoliata confers cold tolerance and modulates peroxidase-mediated scavenging of hydrogen peroxide. Plant Physiol. 162 1178–1194. 10.1104/pp.112.210740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillon O., Aury J. M., Noel B., Policriti A., Clepet C., Casagrande A. (2007). The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature 449 463–467. 10.1038/nature06148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X., Nie X., Liu Y., Zheng L., Zhao H., Zhang B. (2016). A bHLH gene from Tamarix hispida improves abiotic stress tolerance by enhancing osmotic potential and decreasing reactive oxygen species accumulation. Tree Physiol. 36 193–207. 10.1093/treephys/tpv139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Liu T., Nan W., Jeewani D. C., Niu Y., Li C., et al. (2018). Two transcription factors TaPpm1 and TaPpb1 co-regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in purple pericarps of wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 69 2555–2567. 10.1093/jxb/ery101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y. Q., Yang B., Deyholos M. K. (2009). Functional characterization of the Arabidopsis bHLH92 transcription factor in abiotic stress. Mol. Genet. Genom. 282 503–516. 10.1007/s00438-009-0481-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C., Huang X. S., Li K. Q., Yin H., Li L. T., Yao Z. H., et al. (2016). Overexpression of a bHLH1 Transcription Factor of Pyrus ussuriensis Confers Enhanced Cold Tolerance and Increases Expression of Stress-Responsive Genes. Front. Plant Sci. 7:441. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S. W., Rahim M. A., Kim H. T., Park J. I., Kang J. G., Nou I. S. (2018). Molecular analysis of anthocyanin-related genes in ornamental cabbage. Genome 61 111–120. 10.1139/gen-2017-0098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H., Oh E., Choi G., Lee D. (2010). Genome-wide DNA-binding specificity of PIL5, an Arabidopsis basic Helix-Loop-Helix (bHLH) transcription factor. Int. J. Data Min. Bioinform. 4 588–599. 10.1504/IJDMB.2010.035902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kim H. Y. (2006). Functional analysis of a calcium-binding transcription factor involved in plant salt stress signaling. FEBS Lett. 580 5251–5256. 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kool M., Ahrens C. H., Goldbach R. W., Rohrmann G. F., Vlak J. M. (1994). Identification of genes involved in DNA replication of the Autographa californica baculovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91 11212–11216. 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy P., Vishal B., Khoo K., Rajappa S., Loh C. S., Kumar P. P. (2019). Expression of AoNHX1 increases salt tolerance of rice and Arabidopsis, and bHLH transcription factors regulate AtNHX1 and AtNHX6 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 38 1299–1315. 10.1007/s00299-019-02450-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroh G. E., Pilon M. (2019). Connecting the negatives and positives of plant iron homeostasis. New Phytol. 223 1052–1055. 10.1111/nph.15933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Hir R., Castelain M., Chakraborti D., Moritz T., Dinant S., Bellini C. (2017). AtbHLH68 transcription factor contributes to the regulation of ABA homeostasis and drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiol. Plant 160 312–327. 10.1111/ppl.12549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea U. S., Slimestad R., Smedvig P., Lillo C. (2007). Nitrogen deficiency enhances expression of specific MYB and bHLH transcription factors and accumulation of end products in the flavonoid pathway. Planta 225 1245–1253. 10.1007/s00425-006-0414-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei R. H., Li Y., Cai Y. R., Li C. Y., Pu M. N., Lu C. K. (2020). bHLH121 Functions as a Direct Link that Facilitates the Activation of FIT by bHLH IVc Transcription Factors for Maintaining Fe Homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 13 634–649. 10.1016/j.molp.2020.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. H., Qiu F., Ding L., Huang M. Z., Huang S. R., Yang G. S. (2017). Anthocyanin biosynthesis regulation of DhMYB2 and DhbHLH1 in Dendrobium hybrids petals. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 112 335–345. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Guo S., Zhao Y., Chen D., Chong K., Xu Y. (2010). Overexpression of a homopeptide repeat-containing bHLH protein gene (OrbHLH001) from Dongxiang Wild Rice confers freezing and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 29 977–986. 10.1007/s00299-010-0883-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. M., Sun J. Q., Xu Y. X., Jiang H. L., Wu X. Y., Li C. Y. (2007). The bHLH-type transcription factor AtAIB positively regulates ABA response in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 65 655–665. 10.1007/s11103-007-9230-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Gao W., Peng Q., Zhou B., Kong Q., Ying Y., et al. (2018). Two soybean bHLH factors regulate response to iron deficiency. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 60 608–622. 10.1111/jipb.12651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Wu H., Ding Q., Li H., Li Z., Ding J., et al. (2018). The heterologous expression of Arabidopsis PAP2 induces anthocyanin accumulation and inhibits plant growth in tomato. Funct. Integr. Genomics 18 341–353. 10.1007/s10142-018-0590-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Hao X. L., Liu H., Wang W., Fu X. Q., Ma Y. N. (2019). Jasmonic acid-responsive AabHLH1 positively regulates artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 66 369–375. 10.1002/bab.1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. X., Liu C., Zhang Y., Wang B. M., Ran Q. J., Zhang J. R. (2019). The bHLH family member ZmPTF1 regulates drought tolerance in maize by promoting root development and abscisic acid synthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 70 5471–5486. 10.1093/jxb/erz307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]