Abstract

Since 2019, countries in the world have been facing many economic, political, social, and health shocks and challenges that are not easily faced with the COVID‐19 pandemic, including Singapore. Under these conditions, the performance of the governance system in dealing with a pandemic is tested transparently in public. However, the implementation of good governance by the Singapore government itself is carried out by steps and decisions that will be taken and implemented through the digital bureaucracy to the community in order to suppress the positive number of COVID‐19. The application of good governance also needs support other crucial elements that improved by digital bureaucracy, which are transparency, accountability, efficiency and effective.

Keywords: COVID‐19, digital bureaucracy, good governance, pandemic, Singapore government

1. INTRODUCTION AND THEORETICAL BACKGROUND REVIEW

During globalization area, the government's management are based on electronic system as a digital bureaucracy. Yet, as the classic bureaucracy is challenged by a shift from paper‐based to digitized information, the shift also offers transparency, significant productivity gains, and more efficient service delivery.

The role of the Digital bureaucracy in the improvement of good governance appears through the work of the electronic management system to enhance the four basic good governance indicators, as it is not possible to establish good governance without an indicator of transparency, accountability, efficiency and effective (Jangeer & Abdou, 2020, pp. 220–201).

The digital bureaucracy works to ensure and provide transparency in political and administrative act and Transparency in information, presentation and availability to citizens and civil society institutions. The application of digital bureaucracy also plays an important role in activating accountability, through the existence of a system to monitor and control the efficiency of the performance of government institutions, which helps in limiting the spread of corruption in the country. The application of digital bureaucracy also supports efficiency and effectiveness through the functions of electronic planning and electronic regulation that help decision makers to succeed in crises containment.

Therefore, digital bureaucracy considers as a vital key to handle the negative impacts on the crisis of COVID‐19 pandemic). So, digital bureaucracy seeks to achieve the optimal use of resources in a manner that serves the members of society and in a manner that guarantees the rights of future generations and work to address within good governance which helps to face. The aim of this paper is that understanding and explaining the impact of digital bureaucracy in activating the mechanisms of good governance in crises containment, and applying this with the evaluation of the Singapore Government regulations and policies in responding to COVID‐19 pandemic.

2. THE BACKGROUND AND CONCEPTIAL FRAMEWORK

2.1. The background of COVID‐19 pandemic

In early 2020, the world was shocked by a virus outbreak, a virus called the coronavirus or n‐cov19. COVID‐19 is a virus that can cause acute respiratory distress syndrome that leads to lung failure and death that was first discovered in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China at the end of December 2019. This virus is likely from the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, which has been linked to previously confirmed cases. The virus is known to originate from the wet market with intense interaction between sellers and buyers with a minimum level of cleanliness, reports also show that in the market it trades wild animals freely, including snakes, porcupines, and deer. The origin of the virus novel is unknown, but it is most likely to appear in bats, then make a leap to humans through other wild animal hosts (Helen Briggs, 2020).

In its development, the COVID‐19 disease outbreak has spread through 215 countries in the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020, has declared the novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) outbreak a global pandemic (Cucinotta & Vanelli, 2020). COVIDs status declared as a global pandemic due to positive cases spreading outside China that peaked up to 13‐fold increase in the infected country. This virus develops very rapidly due to its characteristic rapid spread through droplets and is supported by human mobility which is very fast even not only done domestically, but across countries. Based on data from the Worldometer, currently positive cases of COVID‐19 in May 20th, 2020 have reached 4,961,283 and spread to 215 countries around the world (Worldometer, 2020). The presence of COVID‐19 as a global pandemic in dealing with the world has created new problems for every country that has been infected with this virus, including Singapore. The total case of COVID‐19 summary in Singapore (as of September 1, 2020, 1200h), cases have reached 1076 positive cases with 27 deaths (Ministry of Health Singapore, 2020). The examination is carried out using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method and molecular rapid test (Tendi Mahadi & Kasus, 2020). The large spread of the COVID‐19 virus from January to May 2020 continues as if it was unstoppable. Delays in early identification of the spread of the virus, weak protection policies for regional entry points in a country or region, delays in the country's systematic response in controlling the spread of the virus, to a small supply of personal safety equipment and health facilities, are among several factors why the spread of the virus has become so massive in various parts of the world, including in Indonesia. As a result of the spread of the epidemic and transmission of the COVID‐19 virus, many people are sick and infected, moreover, it causes death. Not only that, the lack of personal protective equipment for medical personnel, causing medical personnel such as doctors and nurses to be very vulnerable and some are infected with the COVID‐19 virus. This is become the point where the government is tested in all policies and regulations whether it meets the conception of good governance or whether the efforts in good governance have been fulfilled (at least carrying out the entire mandate of Law No. 6 of 2018 on Consequences of Health consistently and in totality) in working together to deal with the COVID‐19 outbreak.

According to some of the statements and problems above, this paper is intended to discuss government regulations and policies in implementing the digital bureaucracy to make a good governance in dealing with the COVID‐19 pandemic and whether the steps taken are appropriate to suppress the positive number of COVID‐19 in Singapore which continues to increase every day.

2.2. The concept of good governance

The concept of good governance is an ancient concept that dates back to the emergence of political organization in human societies. For example, Aristotle distinguished between regimes from the standpoint of goodness and corruption (384,322 m), where he showed that the good system aims at the public good and the corrupt system aims to achieve private interests and rule without the law. Either the term good governance or good governance has its origin in Latin, meaning: the method of managing and directing the ship. In the thirteenth century, the term (governance) was used in the French language as a synonym for the term government, then as a legal term in 1478 and then it included democratic demands as well, but in 1937 (governance) in the English language as a concept for running an economic institution. In the mid‐90s of the last century, the focus became on the political and institutional dimensions of the concept. The shift was made to intensive use of the concept of good governance, particularly by international organizations such as the World Bank, the United Nations Development Program and other international, regional and local organizations, in order to push developing countries to adopt economic and administrative policies. Specific to fight corruption and improve its political and economic performance on the one hand, and improve the effectiveness of international aid provided to it to manage society's affairs in a developmental and developmental direction on the other hand, for example, the World Bank used the term good governance to express governance to denote the improvement of public administration and politics (Faris Alli & Ahmed Mohammad Abdou, ibid).

Good governance is a prominent issue in the management of public administration. This is reflected in among others the intense demands of the people on the State organizers, both in the government, the legislature and the judiciary to organize good governance. This demand came not only from the people of Indonesia but also from the international community (Sjahruddin Rasul, 2012). The concept of “governance” involves not only the government and the state, but also the role of various actors outside the government and the state, so that the parties involved are also very broad (Joko Widodo, 2001, p. 243) The United Development Program (UNDP) defines governance as governance is the exercise of economic, political, and administrative authority to manage a country's affairs at all levels and means by which states promote social cohesion, integration, and ensure the wellbeing of their population. Thus, governance has three related pillars, namely economic, political, and administrative. These three elements must be interconnected and work with the principles of equality, without any effort to dominate one party against the other in order to create good governance itself. Defining the principles of good governance is difficult and controversial. The UNDP Principles and related UNDP text on which they are based (Qudrat I Elahi, 2009, p. 1167; Graham et al., 2003, p. 3) as in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Five principles of good governance

| The five good governance principles | The UNDP principles and related UNDP text on which they are based |

|---|---|

| 1. Legitimacy and voice | Participation—all men and women should have a voice in decision‐making, either directly or through legitimate intermediate institutions that represent their intention. Such broad participation is built on freedom of association and speech, as well as capacities to participate constructively. |

| Consensus orientation—good governance mediates differing interests to reach a broad consensus on what is in the best interest of the group and, where possible, on policies and procedures. | |

| 2. Direction | Strategic vision—leaders and the public have a broad and long‐term perspective on good governance and human development, along with a sense of what is needed for such development. There is also an understanding of the historical, cultural and social complexities in which that perspective is grounded. |

| 3. Performance | Responsiveness—institutions and processes try to serve all stakeholders. |

| Effectiveness and efficiency—processes and institutions produce results that meet needs while making the best use of resources. | |

| 4. Accountability | Accountability—decision‐makers in government, the private sector and civil society organizations are accountable to the public, as well as to institutional stakeholders. This accountability differs depending on the organizations and whether the decision is internal or external. |

| Transparency—transparency is built on the free flow of information. Processes, institutions and information are directly accessible to those concerned with them, and enough information is provided to understand and monitor them. | |

| 5. Fairness | Equity—all men and women have opportunities to improve or maintain their well‐being. |

| Rule of law—legal frameworks should be fair and enforced impartially, particularly the laws on human rights. |

2.3. The concept of digital bureaucracy

To deal with the general concept of bureaucracy, it is necessary to define the meaning of the term bureaucracy, because the term bureaucracy is twofold: the first part (Bureau), meaning office by which means the place from which public business is conducted, for example the post office or the communications office (Mona Ramadan Muhammad Batikh, 2014, p. 81) and this Latin word is close to the French word (la bure) Which means the fabrics used as table cover in the office, and then used later to refer to the office itself. As for the second part (cracy), meaning rule, and the word, in both parts, means office rule or administration through offices, and it may also mean power or rule, and the first to use the term bureaucracy was the French minister Vincent de Gournay in the eighteenth century, as well as the first to look at public offices on It is the working tool in the government. Then the term moved to Germany during the nineteenth century, after which it moved to the English language and other international and international languages (Darwish & Badran, 2008, p. 117).

When discussing the issue of modern bureaucracy (positive bureaucracy), it is necessary to refer to (Max Weber) as an official framework for everyone who writes on this topic. The bureaucracy in the beginning was intended to organize state administrations through offices, and in this sense it means the organization according to which administrative work is carried out on the basis of specialization and the division of work into multiple jobs, with determining the substantive relationships between them regardless of who occupy this organization (Al‐Helou, 2009, p. 16, as well as Ibrahim Abdel Aziz Shiha, previous source, p. 13). Work within it according to general rules and predetermined procedures, and this work is proven in written documents and documents, which is the meaning that Max Weber intended when he established his theory on bureaucracy, which is called the concept of pure bureaucracy and is a model of good management in major administrative organizations such as the government apparatus, the German social scientist Max Weber He treated the theory of the bureaucracy as a rational system commensurate with the industrial society in Western Europe, and he studied the bureaucratic system as an integral part of the comprehensive social system and reached the conclusion that any social system, if it started as a traditional system, will end up being a bureaucratic system. So, the components and elements of the ideal model of bureaucratic organization according to the study and analysis of Max Weber for major governmental organizations include the formal division of work and duties on the members of the organization, as well as the distribution of jobs on the basis of specialization in work and the hierarchy of authority and employee joining the job only through appointment, as well as work performance According to official records and documents according to specific rules and controls. It should be noted that the reason for Max Weber's interest in studying the bureaucratic model stems from his deep belief that this model is the most efficient means for managing major administrative organizations, and that the future of contemporary societies depends on the best use of it (Mona Ramadan Muhammad Batikh, 2014, p. 87–89).

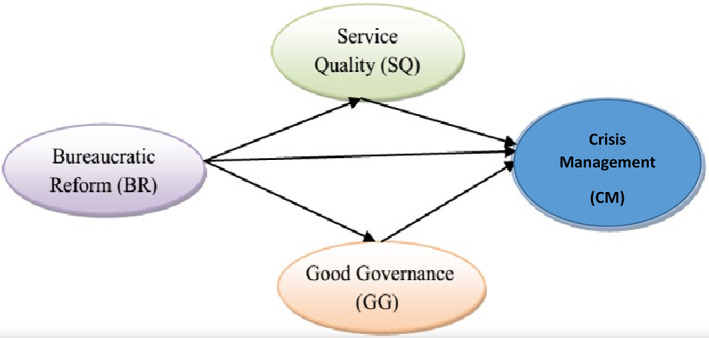

The World Bank defines digital bureaucracy as a modern term referring to the use of information and communication technology in order to increase, efficiency, effectiveness, transparency and accountability of the government in the services provided by the government to citizens to eliminate corruption and encourage citizens to participate in public policies in various sectors. It can be said here that the World Bank affirms that Bureaucracy reform by electronic management is one of the important means in applying service quality and good governance which might help in crisis management. See Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Bureaucracy reform (BR)

Once one begins to entertain the idea that bureaucratic organizations are not necessarily the main reason for the administrative and service crises in public sector experiences all over the world since the 1980s, but rather that the cause can be found in the increased complexity and information overload in the administrative procedures needed to provide public services, we can explore possible solutions to this problem. The solution we propose in this paper is based on bureaucracy reform by the notion of electronic bureaucracy. Even if this term has often been used as synonymous with e‐government, according to the transaction costs model (Cordelia, Antonio, ibid.).

Muellerleile, C., & Robertson, S. L. (2018) believes that it must, nevertheless, be kept in mind that the under pinning rationale that has led us to propose the establishment of Digital bureaucratic forms of government as a primary goal for government policies which is not always compatible with the integrated approach to e‐government that foresees the perfect interdependence and digital interoperability of public offices, for example through a government portal that provides access to government services via an integrated gateway. These policies in fact increase the level of interdependences among public offices, underestimating the problem of increased administrative complexity that is always associated with integration programmers (Edström & Galbraith, 1977).

By Ciborra (1993), the electronic bureaucracies are unambiguous organizational forms with very specific characteristics designed to achieve very specific goals. These are organizations that follow the logic of a bureaucratic mechanism to coordinate the execution of organization activities, and hence to deliver quality services (Kallinikos, 2006). This typology of organization differs, however, from traditional bureau‐cracies because ICTs are now used to facilitate and support the fundamental organizational functions of coordination and control that are defined in the legal‐normative set of rules that prescribe how to coordinate the activities of the organization and how to deliver the quality services. This set of rules is also, as already described, important pillars for enforcing a democratic approach to public service delivery.

Cordelia, Antonio (ibid, pp 265–274) argues that the e‐bureaucratic form is thus recommended as an e‐government policy that helps to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the action of the Singapore while reinforcing the democratic values of equality and impartiality in the interaction of the State with citizens. Singapore's Digital Bureaucracy systems have been highly rated for their extensive strategic and innovative use of information technology. These helps to create good governance in crisis management.

Wong (1998) says that IT in delivering government services. Since the early 1980s, Singapore has continually introduced new information technologies to improve its government business processes. The result has been IT‐knowledgeable human resources, as well as an IT infrastructure that provides citizens with modernizing its vast government infrastructure using IT have been difficult. The process has involved redesigning services, introducing over 1600 e‐services, and learning how to tailor and deploy electronic services. The result has been transformed public services. These investments proved crucial in 2004 when Singapore was hit with the outbreak of SARS.

3. SINGAPORE'S COVID‐19 RESPONSE: POLICIES AND REGULATIONS

Al‐Ameri (2017) says that Singapore has been succeed after its separation from Malaysia in August 9, 1965 in transforming her country from weak state to a strong one by virtue of successful and balanced policies that has been used in the country in the last years ago which make Singapore one of distinguished economic forces in the world, the Singapore government received a worn out country and Singapore was suffering from many problems and crises, especially at the economic level, which made Singapore occupy the last seats globally. For example, the economic level per capita of the national income at the time, it did not exceed the equivalent of 25 U.S. dollars, while the American per capita income at the time was about 1510 dollars, and the main reason for this economic backwardness was the amount of internal turmoil, wars and foreign invasions that Singapore suffered a lot, for more than more A 100 years (from 1819 to 1965) Singapore suffered greatly from administrative, financial, and security corruption, as Singapore was classified at that time as one of the most dangerous places in the world for its exposure to crimes and thefts, as it was dominated by insecurity in a very large way.

As a small island city‐state comprising 5.6 million people, Singapore's well‐defined borders, small population and limited geographical size have made it relatively easy for its policymakers to monitor and restrict the movements of its people. This is compounded by the high levels of political centralization in Singapore, which has allowed the government to pass bills quickly and ensured a high level of social compliance among citizens and residents. Such political centralization is largely attributable to Singapore's single party‐rule, tough laws and extensive co‐optation of political and business interests, all of which have also contributed to its reputation as a “soft authoritarian” state (Barr, 2014; Bell, 1997; George, 2007; Rodan, 2008; Hsu & Tan, 2020).

It is significant to ask that how did Singapore achieve progress and development in different sectors?, and how did the Singapore economy occupy the third place in terms of GDP after the American economy in recent years?, and how did the average per capita income rise to many times in recent years compared to previous years? (Al‐Ameri, 2017). And the answer, in fact, is that the strength of the state lies with the resources it has within its territory and outside it, and with what can be invested and developed in a sustainable manner and good quality service for people by electronic management; This reflects the strength and influence of the state in the political and economic fields at the international level, and this is what applies to Singapore (ibid).

On the one hand, Singapore has enabled to follow an appropriate economic model that enables the Singapore government to transform the massive population problem into a competitive and economic advantage. This model is founded by the famous British economist “Sir Arthur Lewis” in his article on “economic development using the unlimited supply of labor” published in 1954 and won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1979. The Lewis model assumes that the economy is divided into two sectors: one is traditional. It is backward (usually the agricultural sector) where the productivity of the worker is negative or zero and the wage is determined socially regardless of productivity, the other sector is more modern (usually the industrial sector) and the productivity of the worker is positive and his wage is determined by his productivity, and development begins in this model when the workers are transferred from the traditional sector (agricultural) to the modern (industrial) sector after a simple training, which leads to higher productivity in the two sectors (the traditional to reduce accumulation and get rid of disguised unemployment) and (the modern) to increase the productivity of workers, Louis requires that there be a demand for the products produced by the modern sector so that employment continues workers, productivity increases, and hence profitability, are reinvested in the same sector until development takes place and there is equal or equitable balance between wages in both sectors (ibid).

The biggest challenge facing Singapore after the end of the “Cultural Revolution” in the 1970s and 1980s was to change the situation in Singapore and realize the four updates in: industry, agriculture, national defense, science and technology, where the late Singapore leader “Lee Kuan Yew” said: “we should able to build an economic renaissance and make your country the largest country as it dreamed, as he adopted his policy on Singaporean investment himself.” Encouraged by these words, Singapore has experienced rapid development, achieving a double digit economic growth rate (Rashid, ).

Lee Kuan Yew says that the importance of national leaders in building the state, saying, “After several years in government, I realized that the more talented people I chose as ministers, administrators and professionals, the more effective and more successful our policies were.”

Dale Fisher states that (Fisher, 2020), although Singapore is the second country after china affected by the COVID‐19 pandemic, and then the countries of the world followed in sharing the damage, it is noted that Singapore has been able to contain the pandemic significantly compared to many countries in the world, and the main reason is because Singapore has many elements of good governance development Sustainable… (As it made impressive efforts to combat the epidemic, and its detection and testing procedures as well as movement restrictions succeeded in stopping the spread of the COVID‐19 successfully.

In this regard, WHO Director‐General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID‐19—9 March 2020 (WHO, 2020). In addition, the Director of the World Health Organization, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, sent a message to Singapore, on “Twitter,” on February 3, 2020: “The Prime Minister of Singapore is playing an excellent leadership role, in the face of the emerging Corona virus,” adding: “The World Health Organization and Singapore are taking one position to combat the emerging corona virus. Since the beginning” (Arabic Sputnic news). Singapore was praised by the World Health Organization, which said it was “deeply affected” by the country's efforts to search for infected people and its measures to limit disease transmission. Four Harvard University epidemiologists considered that the method used in Singapore to detect cases is also considered “the gold standard.” (Near‐perfect detection; Nihal Tariq, 5252). Singapore ranked 21 in the resilience index thanks to its strong economy, low economic risks, strong infrastructure and low level of corruption. Singapore took early measures to contain the virus that contributed to slowing the spread of the epidemic to a minimum. Constance Tan, who works for the “Konigl” data analysis platform, says that the Singaporean government deals transparently in all steps it takes to combat the epidemic, and that is why people comply with all measures without controversy. The government is relentlessly pursuing violators. However, due to its small size, Singapore's economic recovery will depend on the recovery of the rest of the world (Lindsay Galloway, 2020).

Bureaucracy reform in Singapore has used digital policy which led to good governance in order to create quality service in responding the COVID‐19 pandemic successfully as the following:

Singapore government has implemented public policy for building new qualitative hospitals, each of which can accommodate around 1000 patients, and it transformed a number of buildings into hospitals, and its hospitals in the endemic areas were completely devoted to treating those infected with the virus, isolating them completely from the rest of the patients.

Singapore government has been creation medical examinations for the injured free of charge, and the Singapore government has pledged to pay any treatment cost which is not borne by the citizens' health insurance.

Singapore has published many medical clinics almost everywhere in the country, these clinics known as “fever clinics” were approved during the spread of the SARS virus in the country in 2002.

Singapore authority has dealt very quickly to contain the virus, as it issued firm decisions and implemented them within days. It was also accelerated to discover new cases and track its communication path with others.

Singapore provinces have sent more than 20,000 medical workers to different Province in Singapore, many of whom are volunteers, and thousands have volunteered in the agricultural and transport sectors.

Government provides administration staff and sales, to maintain the continued arrival of key commodities and follow up to patients. This indicates the awareness, behavior and cooperation of the Singapore people during the pandemic crises.

- Regarding to digital bureaucracy, Justin Fong, who hails from Singapore, says pandemic crisis has led to an increase in reliance on technology that will pave the way for Singapore's prosperity as the following:

- Singapore government has turned many medical examinations into online counseling.

- Facilitating the delivery of food and all supplies to the citizens during the epidemic period, as the Singapore authorities imposed a complete closure of all countries, and ordered people to stay in their homes. The majority of people were ordering food online only.

- The government Singapore has turned many medical examinations into online counseling.

- Singapore uses advanced technology to follow up and diagnose cases of COVID‐19 virus infection, such as monitoring methods and means of communication between patients and doctors, as well as allocating Chinese social media to spread awareness and monitor the spread of the virus.

- Singapore government uses advanced technology to follow up and diagnose cases of COVID‐19 virus infection, such as monitoring methods and means of communication between patients and doctors, as well as allocating Chinese social media to spread awareness and monitor the spread of the virus.

- Many companies have set urgent policies to allow their employees to work from home, and the government launched the “TraceTogether” application on the phone, which allows the user to track down those infected with the emerging coronavirus to limit the spread of infection (Lindsay Galloway, 2020).

- The authorities in Singapore decided to use a robot dog, it called “Spot,” to help reduce cases of infection with the coronavirus (Sky News Arabia, 2020).

- The Singaporean government announced Monday that travelers arriving in the country from abroad will wear an electronic monitor if they are not subjected to isolation at a government‐designated facility. The Immigration and Checkpoints Authority said in a statement that this condition, which will come into effect on August 11, aims to “reduce the risk of transmission of COVID‐19 from travelers arriving to the local community.” The authority announced that the rule will apply to all incoming travelers, including returning Singaporeans, who “will need to activate the electronic monitoring device upon arrival at their place of residence.”

- Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong launched that the Smart Nation program at the end of 2014. As part of the program, the Singapore government is using an unknown number of sensors and cameras that allow it to monitor a variety of things from the cleanliness of public spaces to crowd density and the precise movement of each locally registered vehicle. The Smart Nation program is designed to improve government services through technology, support citizen communication, and encourage private sector innovations. For example, creating electronic maps to monitor the possibility of infectious diseases spreading inside buildings (Government website, 2016).

- Other technological means of surveillance include a GovTech‐designed Safe Entry app, a “national digital check‐in system” that allows workplaces, malls, restaurants, supermarkets and other public venues to keep track of the individuals who enter their premises, by requiring individuals to “check‐in” to a premise by scanning a QR code (GovTech, 2020). Existing technologies such as WhatsApp have also been used to keep track of individuals who have been placed under quarantine or stay home notice. These technological tools can therefore be thought of as another form of analytical capacity that can be used to enhance the government's ability to collect and analyze large amounts. Certainly, Singapore is not the only country that has recognized the importance of technological analytical capacities. Similar apps have also been developed and are widely used in China and South Korea.

- Facilitating the delivery of food and all supplies to the citizens during the epidemic period, as the Singapore policy in imposing a complete closure of all countries, and ordered people to stay at homes.

- Political centralization and soft authoritarianism aside, Singapore's experience in managing COVID‐19 also draws from its efficient public administration (Haque, 2009), particularly in its public healthcare system (Ramesh, 2008), and high levels of governing and policy capacity (Cheung, 2008; Guo & Woo, 2016; Lee, 2009; Woo, 2016; Woo et al., 2016). However, these capacities do not exist in a vacuum, nor were they the sole work of a particular leader or administration. Rather, Singapore's policy capacities, especially those that I will discuss below, are the result of a cumulative process of capacity‐building efforts over time.

- There are two aspects of political capacity that are relevant to the case of Singapore government role. The first comprises political trust and legitimacy, while the second involves political communications. Furthermore, the two forms of political capacity are interlinked, with the public's willingness to accept the government's policy announcements dependent on the presence of political trust and effective political communications further building up this trust and hence contributing to the government's political legitimacy. Both communications and trust are crucial for ensuring public compliance with policies and regulations.

- Certainly, much has been written about political trust and legitimacy in Singapore. As an archetypal East Asian “developmental state” that operates on the basis of performance legitimacy and which has systematically reduced civil society's role in public discourse, Singapore exhibits a significant level of socio‐political trust, much of which is predicated upon the state's continued ability to generate economic growth and ensure social stability (Huff, 1995; Liow, 2011; Perry et al., 1997; Woo, 2018). This performance legitimacy is perhaps further enhanced by Singapore's success in managing past crises and pandemics, such as the SARS crisis and the 2008 global financial crisis.

- This emphasis on trust and transparency in public communications was also evident during the SARS crisis, with the government granting World Health Organization (WHO) officials full access to its information and all data and information presented in a daily conference chaired by the Director of Medical Services and attended by key public officials and WHO observers (Centre for Strategic Futures, 2017, p. 14). This practice of daily information sharing has therefore been extended to the COVID‐19 crisis, with the Multi‐Ministry Taskforce on COVID‐19 sharing updates and information with the public through frequent press conferences.

- However, there remains one key deficiency in Singapore's political capacity that may have negatively impacted its COVID‐19 response efforts. Specifically, insufficient communication between the state and Singapore's NGOs, particularly those that deal with the foreign worker welfare, had prevented policymakers from gaining awareness of the cramped and unsanitary living conditions that many foreign workers were made to live in by the employers. These living conditions would naturally give rise to high levels of COVID‐19 infection among Singapore's foreign workers, particularly those who live cheek‐by‐jowl in these dormitories… Singapore's COVID‐19 death rate is among the world's lowest, with only about 0.1 per cent of patients succumbing to the illness here. The statement Signature, 2020 (Rajendran, ).

Making medical examinations for the injured free of charge, and the Singapore government has pledged to pay any treatment cost that is not borne by the citizens' health insurance as well as building new qualitative hospitals in short period.

The case of Singapore has also shown that operational capacities play a key role in the detection, isolation and treatment of COVID‐19, with such operational capacities including physical and technological infrastructure as well as human capital in the form of contact tracers. However, while Singapore has built up significant operational capacities in its healthcare system and public service, there were also deficiencies that may have affected its ability to curb manage the large infection clusters that had emerged in its foreign worker population. However, the TraceTogether app was not widely downloaded by the Singaporean population.

This is about one fifth of Singapore's total population. This suggests a lack of technological literacy among some quarters of the population but more likely, concerns over data privacy and a lack of trust in the government's ability to safeguard individuals' personal data.

By Lee (2020), much of the policy capacities that have contributed to Singapore's ability to manage COVID‐19 fatalities as well as and carry out extensive contact tracing stem from the government's experience with SARS. As Singapore's Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has noted, “we [the Singapore government] have been preparing for this COVID‐19 since SARS, which was 17 years ago.” At the same time, Singapore's struggle to grapple with its high levels of infection also stem from certain deficiencies in its policy capacities.

The emergence of the foreign worker infections can therefore be seen a “black elephant” event, that is, an unexpected shock (similar to a black swan) that has arisen from an already‐known systemic problem that policymakers and society are unwilling to address (akin to an “elephant in the room”) (Centre for Strategic Futures, 2017; Ho, 2008). Black elephant and black swan events are typically the result of insufficient analytical capacities, especially in terms of the channels and mechanisms through which information on worker dormitory infections could have been passed on to policymakers.

Woo (2018), emphases that much of this has to do with the inability of nonprofit and civil society groups to sufficiently gain the attention of policymakers and political leaders, which is in turn a consequence of Singapore's developmental state model of governance. Hence, while information on foreign worker dormitory conditions resided within non‐profit groups, there were insufficient channels of communication between policymakers and civil society, in order that this information could be brought to policymakers' attention. This is somewhat related to Singapore's political capacity, which is discussed next.

It can be seen that digital bureaucracy has been achieved in Singapore to response pandemic crisis. So, digital machinism helps public administration to enhance transparency and accountability, while bureaucracy machinism helps government to operate with efficiency and effectiveness. Therefore, we can say that digital bureaucracy helps to activate the mechanisms of good governance, especially in managing crises, such as the success of Singapore in the face of the pandemic.Indeed, it can be said that one of the most significant features of Singapore's experiences and achieving good governance and sustainable development and reaching what they are now is the gradual implementation of reform such as electronic management, that is, defining the relationship between reform, development and stability on the basis of “Development concepts” compatible with the requirements of the times, in a developing, transitional state typically, like Singapore, the major changes that reform brings will affect its old social structure and its social and political stability by digital bureaucracy. Here it must be emphasized that reform is based on stability and its aim is development. The Singapore approach to openness and reform adhered to the principle of establishing stability first, and this helps to reduce unrest and maintain social cohesion and integration. On this basis, the Singapore government has endeavored to achieve development and promote stability through reform and sustainable development, which has achieved balance and harmony between stability, development and reform (Faris Ali Jangeer, Ahmed Mohammed Abdou, ibid).In any case, the prevalence of performance legitimacy as source and driver of political trust, coupled with the Singaporean state's hitherto ability to overcome crises and continuously generate economic growth, means that political trust has thus far been relatively high. Certainly, some of this can also be attributed to the Singaporean state's “semi‐authoritarian” approach to governance and its low tolerance for dissent (George, 2007; Rodan, 2008; Hsu & Tan, 2020). In any case, the Singaporean state has managed to maintain relatively high levels of political trust and policy compliance, both of which have contributed to its political capacity.Another key to Singapore's experiences is bureaucracy government and seeking development, and leaders with deep in sight and sound policies. Here, the developing country that needs to transform its development mode should unite its people and focus national power to advance economic, social and political reform on a regular basis, so it needs a government use digital bureaucracy. In a certain period and in certain areas, it has strong political power and the ability to manage effectively (Cordelia, 2007). To this effect, Singapore tends to transform from a developing country that suffers from many problems and crises to a country that possesses the elements of real good governance and sustainable development and is able to solve its problems and crises and contain them, but rather the competition of developed countries in the areas of development and progress and provide assistance and support to the countries of the world that need help and expertise, and the Singapore experience in the field of facing and managing the COVID‐19 pandemic crisis is a good model of The application of good governance also needs support other crucial elements that improved by Digital Bureaucracy, which are transparency, accountability, efficiency, and effective. Nevertheless, there is “lack of transparency” and concealment of information related to the Chinese policy toward virus at the beginning of its emergence, which led to its spread worldwide and turned into an epidemic, for example, Zhong Nanshan, known as “the hero of SARS” for his great role in the virus in 2003, and the epicenter of the spread of the new Corona virus, confirms that Chinese government kept secret many details of the virus at the beginning of its appearance.

4. CONCLUSION

The main mechanisms of good governance are transparency, accountability, efficiency and effectiveness and efficiency and effectiveness. In this regards, digital management helps public administration to enhance transparency and accountability, while bureaucracy helps government to operate with efficiency and effectiveness. Therefore, digital bureaucracy helps to activate the mechanisms of good governance, especially in managing crises, such as the success of Singapore in the face of the pandemic.

If digital bureaucracy is to be truly achieved within governments, the transparency, accountability, efficiency, and effective are achieved as an elements of good governance and sustainable development would enable to manage crises with quality service.

Currently, good governance includes all the and necessities of life necessary for the members of society, including health, education, a clean environment, economic prosperity, strong political institutions, sustainable development, quality service, and crisis management.

Good governance works to guarantee the rights of future generations without compromising or harming the rights and needs of present generations.

The COVID‐19 pandemic highlighted the urgent need for digital bureaucracy as an effective tool to eradicate that pandemic, as Singapore's management toward the COVID‐19 pandemic was not came across, but rather as a result of the existence of a truly good governance, sustainable development, and quality service with regards to different dimensions.

Singapore has demonstrated the significance of digital bureaucracy which helps to have sustainable development in the face of crises during the COVID‐19 pandemic, as it managed, in record time, to achieve progress in managing the pandemic by harnessing the elements of its good governance to contain and eliminate that pandemic spatially transparency, Unlike China, there has been a lack of transparency in the face of the pandemic.

The SARS crisis in 2002, had allowed the Singaporean state to launch a strong early response to the COVID‐19 outbreak. These efforts have culminated in Singapore's low levels of COVID‐related fatalities and minimal community transmission within its citizen and permanent resident community. However, deficiencies in Singapore's analytical capacities had also resulted in the state's inability to accurately assess and address the infection risks that came from its densely populated and often badly managed foreign worker dormitories. This has led to a curious outcome of a dual‐track COVID‐19 response with overall COVID‐19 fatalities as well as infection levels among citizens and permanent residents relatively low but infection levels among foreign workers and other work permit holders soaring rapidly. More importantly, these capacity deficiencies explain how a hitherto high‐capacity state such as Singapore could still have ended up with a suboptimal outcome of high infection rates.

The management and response toward the COVID‐19 virus is something that can be achieved if the response plans are followed seriously and precisely, and all of this requires in the end result the availability of the ingredients and requirements for sustainable development.

5. RECOMMENDATION

It can be recommended that decision makers in the all countries over the world should work hard to be able to achieve actual good governance elements as it represents the main key to contain the occurrence and emerging crises.

An industry that adopts a new approach to modernize bureaucracy in line with modern technology and changes in the era of the pandemic. And, within the modern environment in this area, such as Singapore, and its adaptation to the community environment, and strengthening governance in the face of crises such as the responding of pandemic.

The governments of countries should develop the administrative staffs by focusing on changing the values of the administrative employee and using modern administrative concepts and information and communication technology to manage human resources, as the activation of these entrances in the administration bureaucracy in the region helps to achieve quality performance and adapt to developments in the administration.

In order to achieve the rationalization of the bureaucracy of the administration of the countries in the performance of the administrative bodies, an ethical charter must be drawn up with references to moral values and be complementary to the law of the administrative function, and work on transparency in business, in addition to the moral and value concepts of the human element that are based on justice, reason and logic. The basis of general ethics for employee behavior is to improve the quality of performance. All that we mentioned above helps to bring the administration closer to the citizen and increase political participation in the region, which is considered as a form of good governance. Promoting sustainable development as one of the pillars of good governance as an imperative for the success of administrative reforms at the level of the political system, and the necessity to open the way for popular participation, civil society and the private sector in activating accountability within local institutions for public performance.

Enacting laws that support the work of e‐government, such as e‐commerce, e‐signature, and setting an appropriate price for Internet fees… and others.

The digital government should be optimized in the ideal way and not to be useless.

Good governance elements is a continuing manner, so decision makers in the all countries should continue this manner and rather than temporary, phased process in a way that guarantees the requirements of upcoming generations.

Focusing on the scientific aspect and developing digital government to serve all segments of society, as education works to promote the process of transparency, as it makes all individuals and all their specializations able to provide the skills they have acquired in the service of building the good governance process.

All developed and developing countries should be benefited from the Singapore development experience, which transferred Singapore to a qualitative shift from a developing country that suffers from many problems and crises to a developed country where is capable for facing and containing crises. Therefore, Singapore can provide assistance the rest of countries in order to rid them of their crises such as the COVID‐19 pandemic crisis.

Responding global crises before pandemic is different from post‐pandemic. Therefore, post COVID‐19, the governments should combine between soft power as transparency and flexibility, on the other hand, countries should also uses strict enforcement of laws to make efficiency and effective, it means that we call good governance when response global crisis successfully, such as Singapore response pandemic successfully.

In order to achieve the above, and as the beginning of a political movement and a broader and greater activity, the researcher believes that coordination with universities should be made to hold an international conference under the auspices of the United Nations and the World Health Organization, and that the participation should be from decision makers, administrative bureaucracies and bodies Academic and popular at the international level, in order to develop a multidimensional and multi‐level strategy to redraw and formulate new public policies and coordination frameworks structures that contribute to solving or mitigating problems and facing the challenges and crises facing state governments to become rational in managing crises such as the Corona pandemic, According to the principles of the public interest to preserve the present and ensure the future.

Biography

Ahmed Mohammed Abdou is a lecturer at the University of Duhok College of Humanitarian Studies, Peace and Human Rights Department, and he is also teaching in Nawroz University/Political Science Department. He is also working as a coauthor and research assistant in Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC). As well as, he worked as coordinator with UN/IOM. Furthermore, he published academic book in Amazon, and also he published research papers in Journals. Mr. Abdou has participated in many local and international conferences, workshops and forums.

Abdou AM. Good governance and COVID‐19: The digital bureaucracy to response the pandemic (Singapore as a model). J Public Affairs. 2021;21:e2656. 10.1002/pa.2656

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in World Health Organization (WHO) at https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/publishing-policies/open-access

REFERENCES

- Al‐Ameri, I. M. (2017). Development experience in Singapore, Center for Strategic and International Studies, University of Baghdad. Journal of Middle East Research, (45). [Google Scholar]

- Barr, M. D. (2014). The ruling elite of Singapore: Networks of power and influence. I.B. Tauris; [Crossref], [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Batikh, M. R. M. (2014). Public administration between bureaucracy and administrative corruption. Reality and Hope. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D. A. (1997). A communitarian critique of authoritarianism: the case of Singapore. Political Theory, 25(1), 6–32. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Strategic Futures . (2017). Foresight. Prime Minister's Office Singapore; [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, A. B. L. (2008). The story of two administrative states: State capacity in Hong Kong and Singapore. The Pacific Review, 21(2), 121–145 [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Ciborra C. U. (1993). Teams markets and systems: Business innovation and information technology. Cambridge University Press, APA. [Google Scholar]

- Cordelia, A. (2007). E‐government: Towards the e‐bureaucratic form? Journal of Information Technology, 22(3), 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- Cucinotta, D. , & Vanelli, M. (2020). WHO declares COVID‐19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed, 91(1), 157–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwish, M. I. , & Badran, M. M. (2008). Principles of public administration. Arab Renaissance House. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher Dale. (2020)Why Singapore's Coronavirus Response Worked—and What We Can All Learn, nextgov, Retrieved from https://www.nextgov.com/ideas/2020/03/why-singapores-coronavirusresponse-workedand-what-we-can-all-learn/163907/

- Edström, A. , & Galbraith, J. R. (1977). Transfer of managers as a coordination and control strategy in multinational organizations. Administrative science quarterly, 248–263. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway Lindsay(2020), Coronavirus: Which Countries Are Most Able to Recover Post‐Crisis? BBC, Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/arabic/vertcap-52204277 [Google Scholar]

- George, C. (2007). Consolidating authoritarian rule: Calibrated coercion in Singapore. The Pacific Review, 20(2), 127–145 [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- GovTech (2020). SafeEntry‐National digital check‐in system [online]. Retrieved from https://safeentry.gov.sg/ [Google Scholar] H

- Graham, J. , Plumptre, T. W. , & Amos, B. (2003). Principles for good governance in the 21st century (p. 3). Institute on governance. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/63517368/9._Graham__Amos__Plumptre20200603‐39838‐ysrafx.pdf?1591202060=&response‐content‐disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DPrinciples_for_Good_Governance_in_the_21.pdf&Expires=1614283018&Signature=dq206iKcuonAOlrnCgUeU~pBABQwuMWemY5wgSPoVoSeME9ahsOXfKSuhxmmJJOE5pfzAVACbDLBn2XfdN~TU18ucGwbAFQCIvQ6U9pqu~QQmhfk~0EUVITbgeazaiCSvAvULd31xOGHyh7Pr9qraEMDP‐wb~VJWa5qkhUgWEAggQL~VAJhRtoZSxZndCdTLlstNoc~YMqS1ZrfsnHy6gHQx6DSyIy3zF2pOt3mpIM5XbZtxGojuRyqH1E‐6QxfLn1ngk897mfLfCaC7rx2SwTSDNHlm7IOhFMLRJW4Vl8wtvlq9v4koPrEXKd6nLILmcwwK3lVNi3w9eTGTBWFedQ__&Key‐Pair‐Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y. , & Woo, J. J. (2016). Singapore and Switzerland: Secrets to small state success. New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing Co. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, M. S. (2009). Public administration and public governance in Singapore. In Kim P. S. (Ed.), Public administration and public governance in ASEAN and Korea (pp. 246–271). Seoul: Daeyong Moonhwasa Publishing Company; [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs Helen, (2020) Coronavirus: WHO developing guidance on wet markets, Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-52369878

- Ho, P. (2008). Governing at the leading edge: Black Swans, Wild Cards, and Wicked Problems. Singapore: Prime Minister's Office. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, L. Y. , & Tan, M.‐H. (2020). What Singapore can teach the U.S. about responding to Covid‐19. STAT Retrieved from https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/63517368/9._Graham_Amos_Plumptre20200603‐39838‐ysrafx.pdf?1591202060=&response‐content‐disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DPrinciples_for_Good_Governance_in_the_21.pdf&Expires=1614283018&Signature=dq206iKcuonAOlrnCgUeU~pBABQwuMWemY5wgSPoVoSeME9ahsOXfKSuhxmmJJOE5pfzAVACbDLBn2XfdN~TU18ucGwbAFQCIvQ6U9pqu~QQmhfk~0EUVITbgeazaiCSvAvULd31xOGHyh7Pr9qraEMDP‐wb~VJWa5qkhUgWEAggQL~VAJhRtoZSxZndCdTLlstNoc~YMqS1ZrfsnHy6gHQx6DSyIy3zF2pOt3mpIM5XbZtxGojuRyqH1E‐6QxfLn1ngk897mfLfCaC7rx2SwTSDNHlm7IOhFMLRJW4Vl8wtvlq9v4koPrEXKd6nLILmcwwK3lVNi3w9eTGTBWFedQ_&Key‐Pair‐Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA [Google Scholar]

- Huff, W. G. (1995). The developmental state, government, and Singapore's economic development since 1960. World Development, 23(8), 1421–1438 [Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Widodo Joko. (2001). Good Governance; Telaah Dari Dimensi Akuntabilitas, Kontrol Birokrasi Pada Era Desentralisasi Dan Otonomi Daerah, Surabaya: Insan Cendekia.

- Kallinikos, J. (2006). Information out of information: on the self‐referential dynamics of information growth. Information Technology & People. [Google Scholar]

- Jangeer Faris Ali, Abdou Ahmed Mohammed, (2020), The problem of management bureaucracy and building good governance (the Kurdistan Region of Iraq for the period 2005–2019 as an example Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 2020–2021.

- Lee, H. L. (2020). PM Lee Hsien Loong's interview with CNN [online]. Prime Minister's Office Singapore. Retrieved from http://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/PM-interview-with-CNN [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. (2009). Developmentalism, social welfare and state capacity in East Asia: Integrating housing and social security in Singapore. Journal of Asian Public Policy, 2(2), 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Liow, E. D. (2011). The neoliberal‐developmental state: Singapore as case study. Critical Sociology, 38(2). [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Helou Majed Ragheb, (2009) Science of Public Administration and the Principles of Islamic Law, New University Publishing House, Alexandria, p. 16, as well as Ibrahim Abdel Aziz Shiha, previous source, p. 13.

- Muellerleile, C. , & Robertson, S. L. (2018). Digital Weberianism: bureaucracy, information, and the techno‐rationality of neoliberal capitalism. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 25(1), 187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, M. , Kong, L. , & Yeoh, B. (1997). Singapore: A developmental city state. Chichester, England: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Qudrat I Elahi, K. (2009). UNDP on good governance. International Journal of Social Economics, 36(12), 1167–1180. 10.1108/03068290910996981 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, M. (2008). Autonomy and control in public hospital reforms in Singapore. The American Review of Public Administration, 38(1), 62–79 [Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Rasul, S. (2012). Penerapan Good Governance di Indonesia dalam Upaya Pencegahan Tindak Pidana Korupsi. Mimbar Hukum Fakultas Hukum Universitas Gadjah Mada, 21(3), 538–553. [Google Scholar]

- Sky News Arabia—Abu Dhabi , (2020) Singapore uses a "robot dog" to confront Corona, 2020 Retrieved from https://www.skynewsarabia.com/varieties

- Tendi Mahadi, Rekor ! Kasus Jumlah (2020) corona di Indonesia hari ini bertambah 973 kasus, Retrieved from https://nasional.kontan.co.id/news/rekor-jumlah-kasus-corona-diindonesia-hari-ini-bertambah-973-kasus

- WHO , (2020), WHO Director‐General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID‐19, Retrieved from https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-sopening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19–-9-march-2020

- Wong, P. K. (1998). Leveraging the global information revolution for economic development: Singapore's evolving information industry strategy. Information Systems Research, 9(4), 323–341. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, J. J. (2018). The evolution of the Asian developmental state: Hong Kong and Singapore. Routledge; [Crossref], [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, J. J. (2016). Business and politics in Asia's key financial centres‐Hong Kong, Singapore and Shanghai (1st ed.) Singapore: Springer. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, J. J. , Ramesh, M. , Howlett, M. , & Coban, M. K. (2016). Dynamics of global financial governance: Constraints, opportunities, and capacities in Asia. Policy and Society, 35(3), 269–282. [Google Scholar]

- Worldometers The site of worldometers, (2020) Retrieved from https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in World Health Organization (WHO) at https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/publishing-policies/open-access