In 2020, the COVID‐19 outbreak has emerged as a globally significant pandemic. Accurate diagnosis of cases has been identified as a key step in the public health response to this disease. 1 Nasopharyngeal swabs have emerged as an accurate means of diagnosing patients with COVID‐19. 2 These swabs carry a risk of trauma to the anterior skull base, with one previous report of a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak following a nasal swab in a patient with a pre‐existing skull base defect. 3 We describe the first reported case of a CSF leak caused by a COVID‐19 swab in a patient with no prior history of rhinologic or skull base surgery.

Informed consent was obtained from the patient discussed. A 34‐year‐old lady with 2 days of malaise in conjunction with upper respiratory tract symptoms underwent a nasopharyngeal COVID‐19 swab. She had no known history of a skull base defect, previous nasal surgery or idiopathic intracranial hypertension. The swab was performed at a drive‐through clinic where the patient remained in her car whilst undergoing the swab. She experienced a significant amount of pain during the swab with epistaxis immediately following the procedure. Forty‐eight hours following the swab, she developed intermittent clear rhinorrhoea from the right nostril that was precipitated by bending forwards or straining. Several days later, she presented to an emergency department where she was discharged without testing for beta‐2‐transferrin. She then presented to our institution's emergency department 5 days after the development of rhinorrhoea (7 days after the swab). She was neurologically intact with no features of meningism. A sample at this time was found to be positive for beta‐2‐transferrin, confirming CSF rhinorrhoea.

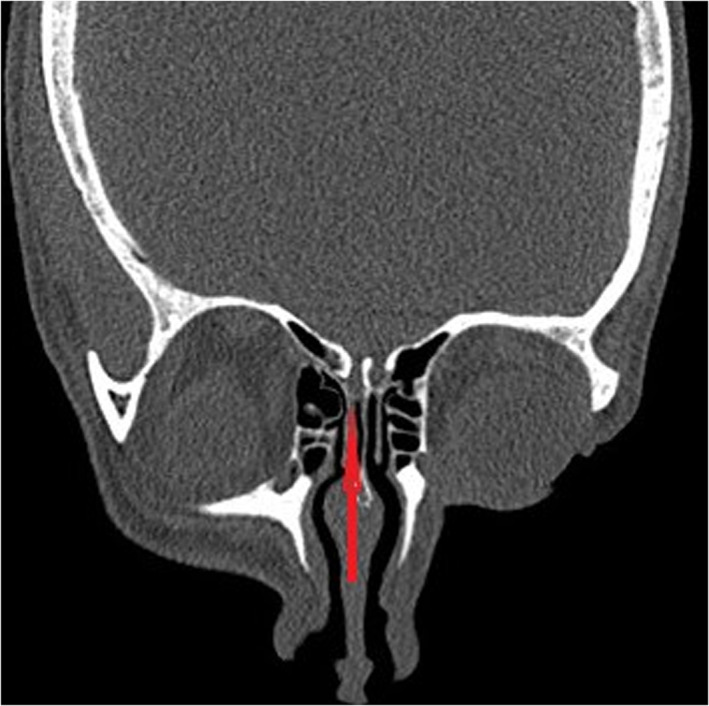

Rigid nasoendoscopy demonstrated no major visible skull base defect. Computed tomography of the skull base demonstrated regions of bone thinning on the right side of the cribriform plate but no definite region of dehiscence (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and MR venography showed no major abnormality or evidence of dural venous sinus thrombosis. The CSF leak was managed conservatively and resolved spontaneously. However, 3 weeks after discharge, she experienced recurrence of clear rhinorrhoea, with the fluid again testing positive for beta‐2‐transferrin. Rigid nasoendoscopy at this time still demonstrated no visible skull base defect. Once again, the rhinorrhoea resolved spontaneously with conservative management. Fundoscopic examination demonstrated no papilloedema to suggest idiopathic intracranial hypertension. A delayed MR imaging again demonstrated no major abnormality.

Fig 1.

Coronal computed tomography slice demonstrating region of thin bone on the right side of cribriform plate.

Surgical intervention has not yet been performed in this patient, but in the event of a further episode of rhinorrhoea that is positive for beta‐2‐transferrin, the plan is for intrathecal fluorescein plus examination of the nose under anaesthesia with skull base repair to be performed if required.

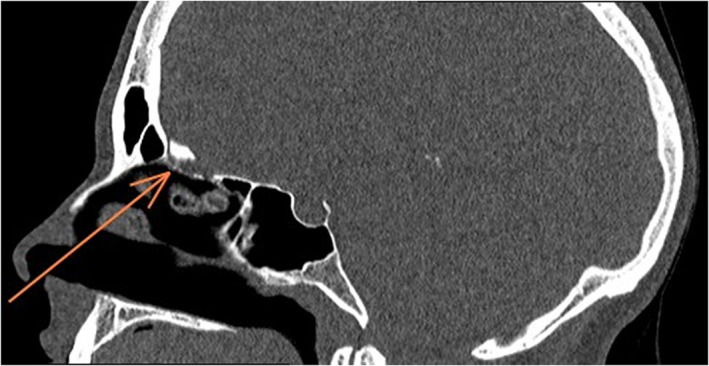

There is one previously reported case of a CSF leak occurring in a patient post COVID swab. 3 This patient had a skull base defect at the fovea ethmoidalis with an associated encephalocele that was traumatized by the swab and underwent surgical repair. 3 Our patient did not have a known existing skull base defect or another condition predisposing to spontaneous CSF leak such as idiopathic intracranial hypertension. We hypothesize that the swab was directed cranially on entering the nose and that the high degree of force utilized was sufficient to penetrate the thin cribriform plate, resulting in the CSF leak. Figure 2 details the likely trajectory of the swab. The size of the defect would not have been large and it is not surprising that the leak eventually resolved spontaneously.

Fig 2.

Sagittal computed tomography slice demonstrating likely trajectory of nasal swab.

Massive numbers of nasopharyngeal swabs are currently being performed in attempts to manage and control the spread of COVID‐19. Testing is currently recommended in patients who are symptomatic or who have been a close contact of a known COVID‐19 case. 4 The increased demand for these swabs has potentially resulted in an inadequate supply of practitioners with experience in performing this test. The correct technique for performing a nasopharyngeal swab has previously been described. 5 Advancing the swab parallel to the palate allows sampling of the nasopharynx and avoids unintended trauma to the anterior skull base. The high volume of testing currently being performed makes rare complications more likely to occur on a population level. Clinicians should be aware of this rare complication.

This is the first reported case of a CSF leak following a nasopharyngeal swab in a patient without an existing skull base defect. Although rare, iatrogenic CSF leak is a real risk of nasopharyngeal swabs. Ensuring appropriate technique while obtaining the swab may help to minimize the possibility of this complication.

Author Contributions

Christopher Ovenden: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; writing‐original draft; writing‐review & editing. Vishal Bulsara: Data curation; formal analysis; writing‐review & editing. Sandy Patel: Data curation; formal analysis; software; writing‐review & editing. Erich Vsykocil: Writing‐original draft; writing‐review & editing. Rowan Valentine: Methodology; supervision; validation; visualization; writing‐original draft; writing‐review & editing. Alkis Psaltis: Investigation; supervision; writing‐review & editing.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . WHO report of the WHO‐China joint mission on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). 2020. [Cited Nov 2020.] Available from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf

- 2. Patel MR, Carroll D, Ussery E et al. Performance of oropharyngeal swab testing compared with nasopharyngeal swab testing for diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019—United States, January 2020–February 2020. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020; 72: 403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sullivan CB, Schwalje AT, Jensen M et al. Cerebrospinal fluid leak after nasal swab testing for coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020; 146: 1179–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kovoor JG, Tivey DR, Williamson P et al. Screening and testing for COVID‐19 before surgery. ANZ J. Surg. 2020; 90: 1845–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marty FM, Chen K, Verrill KA. How to obtain a nasopharyngeal swab specimen. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020; 382: e76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]