Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Editor

Diverse cutaneous manifestations of coronavirus disease‐2019 (COVID‐19) have been reported including morbilliform, pernio‐like, urticarial, vesicular and papulosquamous eruptions. 1 In the context of association between COVID‐19 and sarcoidal granulomas, only one case of sarcoid‐like granulomatous subcutaneous nodules was reported, which developed 2 to 3 weeks after the COVID‐19 diagnosis. 2 We report on a case of sarcoidal granulomas mimicking scar sarcoidosis in a patient diagnosed with COVID‐19.

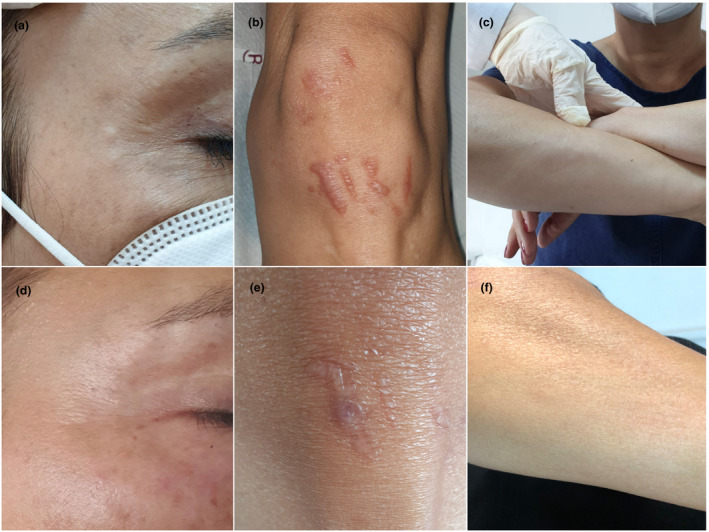

A 55‐year‐old woman presented with infiltrated, reddish and tender plaques over old scar sites on both knees, multiple, rounded, mobile and tender subcutaneous nodules of 1–2 cm in diameter on both arms, three subcutaneous papules measuring 3–4 mm on periorbital areas and a single papule in the glabellar region (Fig. 1a–c). Papules on periorbital and glabellar areas corresponded to the sites of botulinum toxin‐A injection that had been performed three months earlier. The patient had a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia and hypothyroidism.

Figure 1.

(a, b, c) Subcutaneous papules on periorbital areas at the sites of botulinum toxin‐A injection (a), multiple, infiltrated and reddish plaques in old scar sites (b), and subcutaneous nodules on both arms (c); (d, e, f) all cutaneous sarcoidal lesions were almost completely resolved within four months.

On 9 March 2020, she had had sore throat, cough, fatigue, arthralgia and anosmia, for which a nasal swab test by reverse transcriptase real‐time polymerase chain reaction (RT‐rtPCR) yielded a positive result for COVID‐19 infection. She had been followed up without treatment for 10 days. One month after the first manifestations of COVID‐19, she had noticed swelling of her old scars. One month later, small papules appeared at the sites of the botulinum toxin‐A injection as well as multiple larger subcutaneous nodules in both elbows.

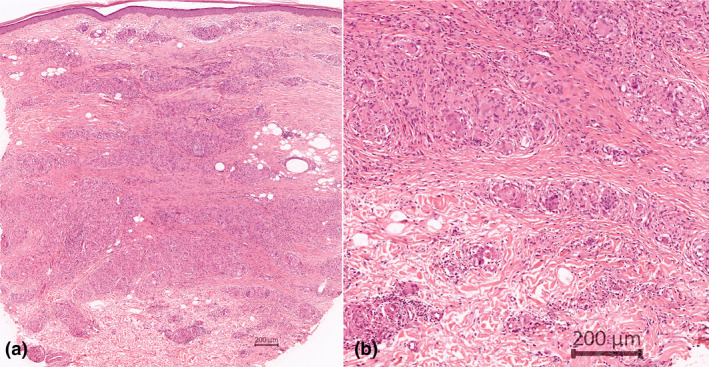

Histopathological examination of a punch biopsy from an infiltrated plaque on old scar showed non‐necrotic, naked granulomas in the superficial and deep dermis suggestive of a sarcoidal granuloma (Fig. 2). An excisional biopsy of a subcutaneous nodule showed similar findings. We then investigated some possible viral traits through subjecting both specimens of sarcoidal granulomas to RT‐rtPCR testing to detect viral RNA from blood. Two sets of RNA samples were extracted from formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens using the FFPE RNA kit (Qiagen RNeasy, Germany). RT‐rtPCR was performed using Bio‐Speedy® COVID‐19 RT‐qPCR Detection Kit (Bioeksen, Turkey) on a Rotor‐Gene Q 5plex real‐time PCR device (Qiagen, Germany). Both samples were negative for COVID‐19.

Figure 2.

(a) Panoramic view of punch biopsy shows granulomatous inflammation in the entire dermis, especially in the lower half (HE [haematoxylin–eosin]); (b) well‐delimited granulomas formed by histiocytes and many giant cells. Few lymphocytes participate (HE).

A biopsy from the labial minor salivary gland, a chest X‐ray, blood chemistry tests and pulmonary and ophthalmologic examinations showed no involvement of sarcoidosis. Serum antibody testing including immunoglobulin (Ig) M and IgG against nucleocapsid proteins of COVID‐19 yielded positive results four months after the infection. As there was no evidence for systemic sarcoidosis, the patient was followed up without treatment. Her lesions began to regress spontaneously within one month. At the next visit, which corresponded to 8 months after the diagnosis of COVID‐19, facial lesions had resolved, subcutaneous nodules substantially diminished, and the scar lesions become paler with a slight induration (Fig. 1d–f). Serologic testing was negative for IgM, but positive for IgG with an increase by 30% from the baseline, the latter was still positive at high titers at 13 months.

Sarcoidal granulomas are characterized by compact, epithelioid, non‐necrotizing lesions with varying degrees of lymphocytic inflammation, resulting from an excessive immune response through activation of mainly T helper‐1 (Th1) and, in part, Th17 cells and release of cytokines including interleukin 2 (IL‐2), IL‐12, IL‐17, IL‐22, interferon γ (IFN‐γ) and tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α). 3 At earlier phases of granuloma formation, a higher production of TNF‐α, IFN‐γ and IFN‐γ‐mediated activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 have been shown. 4

In cases in which primary sarcoidosis is ruled out, sarcoidal granulomas may develop as a result of immune response and delayed‐type hypersensitivity reaction to various antigenic stimuli. 3 , 5 Thus, COVID‐19, where type‐I IFN is considered to play an essential role in the first‐line antiviral defence, might well have served as an antigenic trigger in our case. 6 Moreover, IFN‐γ has been reported to play a central role in COVID‐19‐related cytokine storms. 7 Increased expression of IFN‐γ in CD4+ T cells followed by activation of adaptive immune responses may have initiated sarcoidal granuloma formation. Trauma areas, i.e. scar and injection sites, which are of high antigenic content, might be primarily affected from COVID‐19‐triggered immunologic reactions, particularly cytokine storms.

Currently, cutaneous sarcoidal granulomas are not included among the skin lesions associated with the COVID‐19 infection, possibly because of the rarity and late occurrence of the symptoms. The exact pathophysiology of late manifestations of COVID‐19 is yet to be clarified. A delayed immunologic response triggered by prolonged or late cytokine storms might give rise to granulomatous lesions which might be challenging, if localized over old scar sites mimicking scar sarcoidosis, as in the present case. This case may suggest a causal relationship between viral infections and sarcoidal granulomatous reactions.

Funding sources

None.

Acknowledgement

The patient (Ş.G.K.) presented in this manuscript gave written informed consent tothe publication of her clinical details. We thank her for an excellent cooperation with the authors during her follow‐up.

References

- 1. Seirafianpour F, Sodagar S, Pour Mohammad A et al. Cutaneous manifestations and considerations in COVID‐19 pandemic: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther 2020; 33: e13986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Behbahani S, Baltz JO, Droms R et al. Sarcoid‐like reaction in a patient recovering from coronavirus disease 19 pneumonia. JAAD Case Rep 2020; 6: 915–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. Cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 66(699): e1–e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crouser ED, White P, Caceres EG et al. A novel in vitro human granuloma model of sarcoidosis and latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2017; 57: 487–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Inaoka PT, Shono M, Kamada M, Espinoza JL. Host‐microbe interactions in the pathogenesis and clinical course of sarcoidosis. J Biomed Sci 2019; 26: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xie B, Zhang J, Li Y, Yuan S, Shang Y. COVID‐19: imbalanced immune responses and potential immunotherapies. Front Immunol 2021; 11: 607583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fajgenbaum DC, June CH. Cytokine storm. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 2255–2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]