Abstract

Purpose

In an era of the COVID‐19 pandemic, improving health outcomes for diverse rural communities requires collective and sustained actions across transdisciplinary researchers, intersectoral partners, multilevel government action, and authentic engagement with those who carry the burden—rural communities.

Methods

Drawing from an analysis of transcriptions and documents from a national workshop on the “State of Rural Health Disparities: Research Gaps and Recommendations,” this brief report underscores the gaps and priorities for future strategies for tackling persistent rural health inequities.

Findings

Four overarching recommendations were provided by national thought leaders in rural health: (1) create mechanisms to allow the rural research community time to build sustainable community‐based participatory relationships; (2) support innovative research designs and approaches relevant to rural settings; (3) sustain effective interventions relevant to unique challenges in rural areas; and (4) recognize and identify the diversity within and across rural populations and adapt culturally and language‐appropriate approaches.

Conclusion

The COVID‐19 public health crisis has exacerbated disparities for rural communities and underscored the need for diverse community‐centered approaches in health research and dedicated funding to rural service agencies and populations.

Keywords: chronic disease, community interventions, COVID‐19, health disparities, rural health

Rural Americans, who comprise 20% of the US population (one in five Americans) and nearly 60 million people, face disparities that result in worse health care than that of urban and suburban residents. 1 More than 90% of US landmass is rural, defined as any population, housing, or territory not in an urban area. According to a 2015 National Rural Health Association study, the death rate for rural areas in 2014 was 830.5 per 100,000 people, as compared with an urban rate of 704.3. 1

Americans living in rural areas are more likely to die from five leading causes of death (heart disease, cancer, accidental injuries, chronic lower respiratory disease, and stroke) than their urban counterparts. 2 , 3 Rural risk factors for health disparities include geographic isolation (including fewer transportation options), lower socioeconomic status, higher rates of health risk behaviors, and limited job opportunities. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic coupled with intertwined risk factors exacerbates the vulnerabilities in rural areas. Evidence suggests that rural populations, compared to their urban peers, exhibit diminished access to testing and treatment availability to combat COVID‐19. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 Existing inequities in health care access confronting rural populations are being amplified during the current pandemic; these include, for example, crumbling hospital infrastructures shaping diminished access to ICU beds and ventilators, and lack of access to infectious disease specialists and major academic medical centers. 9 , 10 Rural counties face unique and diverse employment‐related challenges to combat COVID‐19 successfully, such as a predominance of employment sectors that raise risk susceptibility for infection and further community spread, such as US agricultural and food production, essential service industries, and agrarian farm working. 6

In an era of COVID‐19, closing the rural health disparities gap and improving health outcomes for diverse rural communities requires collective and sustained actions across transdisciplinary lines, including both researchers and intersectoral partners. Multilevel government action and authentic engagement with those living in rural communities who carry the burden are needed.

Drawing from an analysis of transcriptions and documents from a national workshop on the “State of Rural Health Disparities: Research Gaps and Recommendations,” this brief report underscores the gaps and priorities for future strategies for tackling persistent rural health inequities.

METHODS

In July 2018, the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), together with its National Institutes of Health (NIH) cosponsors and in collaboration with the Health Resources and Services Administration and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (Office of the Surgeon General), convened a workshop on the “State of Rural Health Disparities: Research Gaps and Recommendations.” The workshop gathered public health leaders in order to examine current research findings on rural health disparities. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 It also provided an opportunity for scientists from diverse disciplines, community‐based interventionists, and clinicians to come together to catalyze and shape the future research agenda for this often‐overlooked critical area. Participants were from 5 of the 10 federal regions, 13 states, and 4 tribes. The workshop content featured four theme areas:

Health promotion and disease prevention in rural areas;

Health disparities within the rural population;

Approaches to managing chronic conditions in rural areas; and

Environmental influences, including technology, on rural health.

Analysis

Using a qualitative approach, several data sources were triangulated from the workshop: detailed summary notes taken by the moderator and other NINR staff, transcription of digital video recordings, Microsoft PowerPoint presentations, and executive summaries. 32 A professional company transcribed the digital video recordings of the presentations and in‐depth discussions. A detailed executive summary of the workshop is available online via the NINR/NIH website. 32 Consistent with qualitative methodology, an iterative process was used that involved a combination of open and focused coding techniques. First, two of the coauthors organized the codes according to the workshop's initial four thematic areas. Next, open coding was employed to identify new and cross‐cutting themes in the context of the texts in the transcribed proceedings and summary notes.

Findings

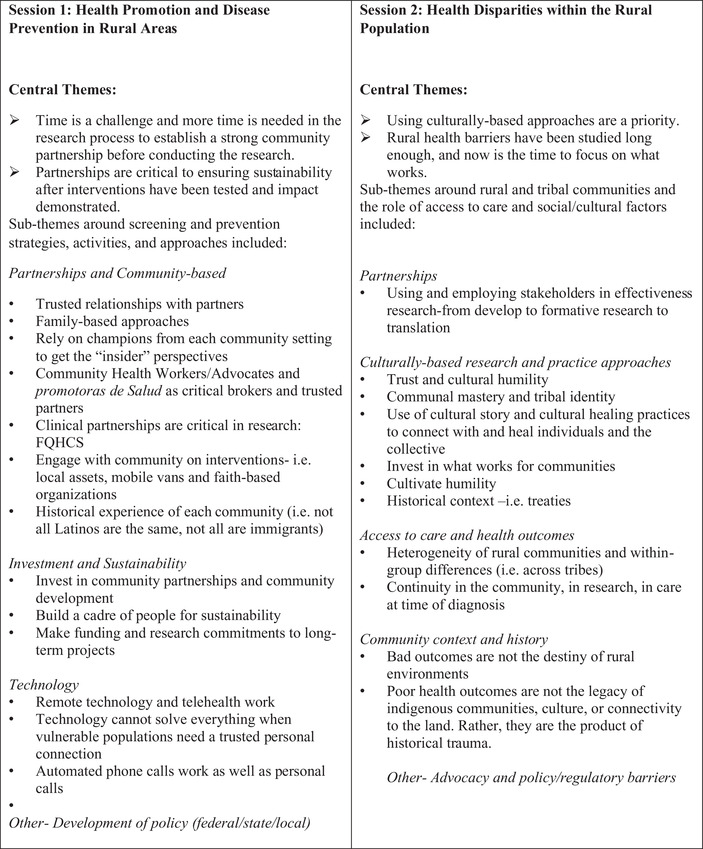

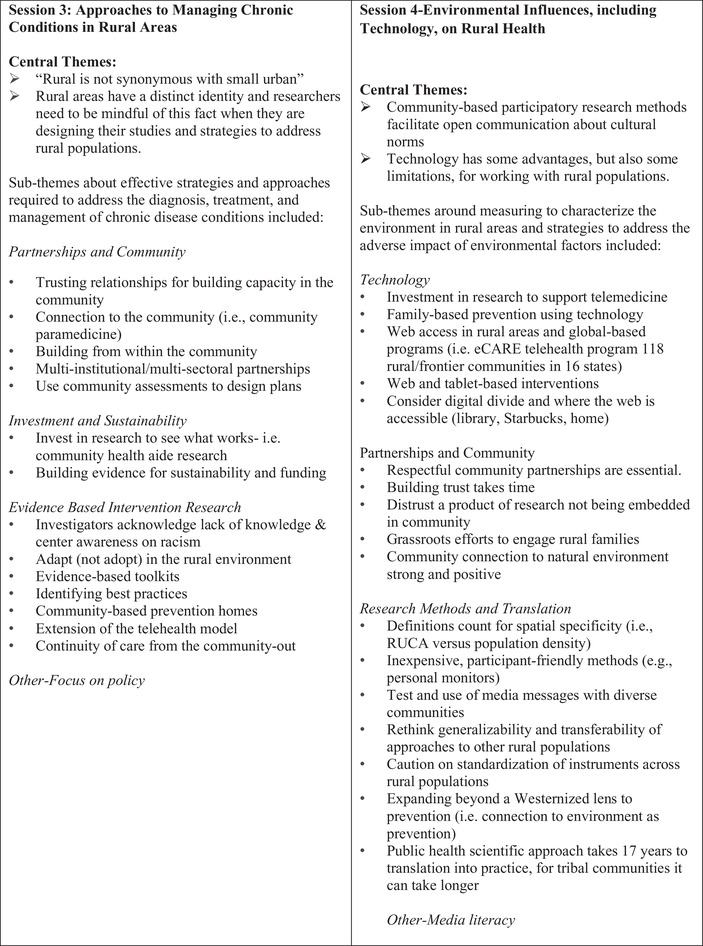

Figure 1 summarizes the central themes and subthemes by each of the four sessions. There was overall consensus among participants that “rural health has been overlooked to a great degree” and needs to be placed as a priority on the national agenda. Another overarching theme is that collectively, we need to go beyond describing the problem to “finding real solutions together and developing action‐oriented recommendations.” Cross‐cutting themes that emerged from the analysis are described below and focused on sharing evidence and community‐based interventions that are sustainable and work for diverse rural communities.

Figure 1.

Central themes and subthemes

Rural communities are heterogeneous

Presenters and participants highlighted the need to move away from a monolithic approach to doing research with rural communities. When considering access to care, clinical‐community interventions, and health outcomes, it is imperative to embrace heterogeneity of rural communities and within‐group differences. Several presenters and participants underscored the role of understanding history and racism and their intersections with “place” as they impact health outcomes. For example, one indigenous scholar stated, “It's important to understand who indigenous peoples are today and to also look at our past that leads us to our current health disparities.” Another scholar working with southern communities in the US‐Mexico border region encouraged researchers and public health practitioners to “Not treat all Latino communities as the same. Not all are Mexican Americans and not all Latinos are immigrants.”

A final message supporting this theme was to continue to reflect on the impact of community context and history as it relates to poor health outcomes. This moves beyond blaming the individual or placing stigma on the community.

Partnerships and communities are central to advancing rural health

The centrality of partnerships and community engagement was consistent throughout the workshop. One participant noted, “The wisdom that will create the best interventions and the best ways to deliver them already exists within the community.” An overarching suggestion was to start with trust and continue the relational processes and long‐term commitment of earning trust with rural communities. Discussions also focused on recentering research from within the community and underscored the need for NIH to create mechanisms to allow its research community the time to build sustainable relationships.

Participants and presenters proposed multiple strategies for strengthening community and intersectoral partnerships, including: (1) engage stakeholders in effectiveness research––from development to formative research to translation; (2) incorporate family‐based approaches to prevention and treatment; (3) rely on champions from each community setting to get the “insider” perspectives in developing interventions and conducting research; (4) work with community health workers as trusted partners; (5) facilitate clinical partnerships in research with health centers; and (6) integrate local assets, including faith‐based organizations and faith‐placed interventions. One of the expert scholars affirmed that, “The best possible care will come from people who know the community. Community can make connections that researchers can spend years studying and never get quite right.”

Rethink research approaches and methods

Presenters and the other participants discussed a range of opportunities for rethinking how intervention research is conducted with rural communities. All agreed that urban strategies do not translate well to the study and treatment of rural health disparities. Several discussions focused on the need to rethink generalizability and transferability of approaches to other rural populations.

One presenter acknowledged that, “The ‘elephant in the room’ that we need to acknowledge is that the research methods we do are almost impossible to do in rural environments.”

Examples of specific strategies to support “rural‐centric” research included: specificity in defining “what and who is rural” and selecting a metric that works such as using rural urban commuting area (RUCA) codes versus population density; using inexpensive, participant‐friendly methods (e.g., personal monitors); being cautious on standardization of instruments across rural populations; and expanding beyond a Westernized lens to prevention (i.e., connection to environment as prevention).

Telehealth or other remote technologies in a variety of rural settings

As noted in the workshop, “technology offers opportunities to address rural health disparities, but investigators must recognize that not everyone has easy access to the Internet and cell phones.” Technology is often seen as an opportunity to expand the reach of interventions in remote settings. While this may be true, and the use of telemedicine has proved effective in many areas, focusing exclusively on technological solutions likely ignores the underlying cultural values of many in rural settings. While one of the sessions specifically addressed the use of technology as an innovation, other discussions included various strategies for incorporating remote technology and telehealth work in rural settings. For instance, one presenter shared “With regards to building trust in relationships with rural communities, I don't think technology can solve everything. When you are vulnerable, people want to talk to a trusted person who is genuinely interested.”

Investment in long‐term partnerships and research capacity building

An overarching concern in the workshop was the lack of sustainability of effective interventions. One presenter and senior scholar affirmed that, “This work requires more time, more money, and more flexibility to adjust the proposed approach to align with what the community still says will work.” Both building evidence for sustainability and investing in evidence‐based interventions were considered key priorities for long‐term research and practice capacity‐building in rural communities. Several other discussions confirmed that interventions must also work within the socioeconomic and financial constraints of a rural context. A few examples of successful strategies included: investing in community partnerships and community development; building a cadre of people for sustainability; and making funding and research commitments to long‐term projects.

CONCLUSION

The analysis from the workshop underscored the challenges and triumphs of rural health disparities research and helped identify gaps and opportunities for research targeted at rural populations. There was consensus on several points.

First, it was agreed that there is a strong need for NIH to create mechanisms to allow its research community the time to build sustainable community‐based participatory relationships. It was emphasized at the workshop that community‐based research is a necessary approach for conducting health research in rural areas. Community‐based approaches foster an atmosphere of shared resources and learning and greatly increase the likelihood that knowledge and services remain in the community, benefiting its residents.

Unknown at the time of the Rural Health Workshop was how much the world could change in the coming years. The COVID‐19 pandemic has shaken all our lives, led to extreme levels of death and disease, and disrupted normal business functioning. The pandemic has had a direct impact on the ability of communities, especially those in remote areas, to maintain healthy and consistent forms of communication and service. Community‐based participatory research, one of the most strongly recommended approaches to addressing issues in rural settings, is necessarily affected by the current conditions as this methodological approach is built on person‐to‐person interaction.

A strength of the service community, and of the population in general, is the ability to adapt to difficult circumstances. Overwhelming as the pandemic is, the service community has done an amazing job of continuing to address the needs of the population, whether through safe practices in direct service environments, such as hospitals, or through technologically focused outreach. One of the recommendations of the workshop participants was to maximize, wherever and however feasible, the use of technological tools in meeting the needs of rural residents. They were clear to indicate that this should not be done at the expense of more direct, face‐to‐face interaction, but they, nonetheless, recommended exploring technological options. In fact, many of the workshop participant presentations shared examples using technology.

The explosion of social media, well before the pandemic and for both good and bad, suggests that the population is ready for remote learning and interaction. This year alone, an amazing number of Zoom (Zoom Technologies Inc., San Jose, CA) (or other) meetings, trainings, and political events have occurred, as well as even entire virtual conferences. The challenges rural communities face are real—limited access to rapid speed technology and support for these resources—but mobile media such as cell phones are ubiquitous even in rural areas. During these unprecedented times, maximizing technological tools, as the workshop paricipants suggested, may help to sustain the momentum.

Second, it has been suggested by many, and for many years, that urban strategies do not translate well to the study and treatment of rural health disparities. The environments and populations in rural areas are very different, and therefore call for a very different set of strategies to address their health concerns. More innovative research designs and approaches relevant to rural settings are needed.

As noted above, the pandemic's disrupting influence has affected our ability to provide, or the population's access to, needed services. While rural residents are appropriately resistant to “copying” urban models, technology may allow for better transferability of existing service models. The historical error to avoid is a simple transfer of existing programs and interventions. There are ways technology can make adaptation easier. Holding online focus groups to determine service content, creating prototypes of service approaches and then re‐engaging community members for their feedback (part of an iterative process), seems feasible in the current climate. These approaches are typically cheaper, lead to quicker turnaround, and can be done with greater frequency. It may be idealistic to think so but perhaps enhanced technological approaches can increase the amount of outreach and exposure service communities can achieve.

Third, and a problem not unique to rural areas, is the lack of sustainability of effective interventions. Numerous researchers and planners have sought to generate the widespread adoption of interventions with varied success. Dissemination and implementation strategies in rural areas should be included as a fundamental component of future research efforts.

Finally, it is crucial to define rurality and recognize rural residents as a special but heterogeneous population. Just as there is great variety in the nature of urban populations and environments, rural areas are quite diverse (e.g., race/ethnicity and economic industries).

Next steps

In March 2020, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) was signed into law and appropriated an initial $1 billion for the NIH to support research, including research on coronavirus and developing countermeasures to prevent and treat COVID‐19 disease. 33 Two subsequent phases of appropriations have totaled $909.4 million to NIH, which has released funding through competing supplements, administrative supplements, and new awards since March 2020. 34 Included is nearly $234 million to improve COVID‐19 testing for underserved and vulnerable populations as part of a Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) initiative, which focuses on populations disproportionately affected by the pandemic. The initiative has four programs: RADx Tech, RADx Advanced Technology Platforms, RADx Underserved Populations, and RADx Radical. 35

For the purposes of promoting greater engagement and health promotion in rural communities, however, the NIH and other service agencies could direct resources to grants specifically aimed at addressing health disparity gaps in rural communities. Grant and contract initiatives that allow for the development of technological solutions to rural health problems could be undertaken, with a faster time frame than typical NIH application and decision timelines. A model already used in the NIH and several other government agencies is the small business research program. This grant program requires researchers to develop health‐based technological solutions in a multiphase approach. Phase I is a 6‐month feasibility study, involving the development of a prototype tool and basic user testing. In its current form, this funding is restricted to for‐profit small businesses. But it is not hard to imagine an expansion of this model to all types of service sector groups, with an approach that allows for quicker turnaround.

Addressing rural health disparities also aligns with Healthy People 2020 and 2030 goals of achieving health equity and eliminating health disparities, attaining high‐quality, longer lives free of preventable disease, and creating social and physical environments that promote good health across the life span. The NINR workshop also brought to the forefront other efforts ongoing at NIH in rural health disparities. For example, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, an active participant in the NINR‐led workshop) hosted a Rural Health Day in November 2019. This has spurred leadership at another NIH Center, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), to approve a rural health seminar series at NIH. These additional events show not only an increasing awareness of the importance of rural health needs, but a commitment on the part of NIH to provide funding to help find solutions.

These efforts are admirable and may well lead to progress in addressing rural health needs. But there is a risk that this additional attention to general rural health needs will fall by the wayside in light of COVID‐19, which has led to the redirection of many resources to finding vaccines or treatments. Health systems, including rural hospitals, have had to devote their existing resources to the immediate needs of an ailing population, while continuing efforts to promote the safest practices to reduce the risk of exposure to COVID‐19.

While it certainly will be more challenging to find resources and to promote meaningful interaction across vastly diverse rural settings, the need is no less real. In fact, if anything, COVID‐19 has highlighted the difficult realities across a vast spectrum of Rural America. Recognizing the heterogeneity of rural communities and capitalizing on the recommendations of the workshop participants discussed in this paper are critical. Some examples might include: (1) setting aside funding and other resources whenever and however possible to rural service agencies and populations; (2) maximizing the use of technological tools—though this was a limited recommendation from the workshop, the time may be ripe; and (3) maintaining the engagement of rural communities perhaps through more seminars, virtual workshops, and focus groups to assess the current conditions and what services and resources might be helpful. These strategies will not solve the current problems, but they seem implementable and might keep the energy moving forward.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors recognize the leadership from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), together with its National Institutes of Health (NIH) cosponsors (National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, Office of Research on Women's Health, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, and Office of Disease Prevention). The authors would also like to thank the Workshop Planning Committee, speaker participants, and all attendees who contributed to the content and success of this event. We would like to thank the following individuals for their contribution to this paper: Debra K. Moser, PhD, RN, FAAN, Professor at the University of Kentucky, College of Nursing for her feedback during early conceptualization of this paper, and Carlos Antonio Linares Koloffin, MD, for his review of the literature and formatting of the paper. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, or the United States Department of Health and Human Services. The recommendations are not intended to constitute an “authoritative statement” or imply funding endorsement by the National Institutes of Health.

Cacari Stone L, Roary MC, Diana A., Grady PA. State health disparities research in Rural America: Gaps and future directions in an era of COVID‐19. Journal of Rural Health. 2021;37:460–466. 10.1111/jrh.12562

REFERENCES

- 1. The United States Census Bureau . What is Rural America? 2017. Accessed January 15, 2020. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2017/08/rural‐america.html

- 2. Warshaw R. Health Disparities Affect Millions in Rural U.S. Communities. 2017. Accessed June 22, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/health-disparities-affect-millions-rural-us-communities

- 3. Daniel H, Bornstein SS, Kane GC, for the Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians . Addressing social determinants to improve patient care and promote health equity: an American College of Physicians Position Paper. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(8):577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Rural Americans at Higher Risk of Death from Five Leading Causes. CDC Online Newsroom. Accessed January 14, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2017/p0112-rural-death-risk.html

- 5. Heath S. Strategies for Rural Patient Healthcare Access Challenges. Accessed March 26, 2020. https://patientengagementhit.com/features/strategies-for-rural-patient-healthcare-access-challenges

- 6. Fehr R, Kates J, Cox C, Michaud J. COVID‐19 in Rural America – Is There Cause for Concern? 2020. Accessed June 22, 2020. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/covid-19-in-rural-america-is-there-cause-for-concern/

- 7. Millett GA, Jones AT, Benkeser D, et al. Assessing differential impacts of COVID‐19 on Black communities. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;47:37‐44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Henning‐Smith C, Tuttle M, Kozhimannil KB. Unequal distribution of COVID‐19 risk among rural residents by race and ethnicity. J Rural Health. 2020;37(1):224‐226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dandachi D, Reece R, Wang EW, Nelson T, Rojas‐Moreno C, Shoemaker DM. Treating COVID‐19 in Rural America. J Rural Health. 2021;37:205‐206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peters DJ. Community susceptibility and resiliency to COVID‐19 across the Rural‐Urban Continuum in the United States. J Rural Health. 2020;36:446‐456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davis TC, Rademaker A, Bailey SC, et al. Contrasts in rural and urban barriers to colorectal cancer screening. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37(3):289‐298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davis TC, Rademaker A, Bennett CL, et al. Improving mammography screening among the medically underserved. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):628‐635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schoenberg NE, Studts CR, Shelton BJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a faith‐placed, lay health advisor delivered smoking cessation intervention for rural residents. Prev Med Rep. 2016;3:317‐323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schoenberg NE. Enhancing the role of faith‐based organizations to improve health: a commentary. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(3):529‐531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parra‐Medina D, Mojica C, Liang Y, Ouyang Y, Ramos AI, Gomez I. Promoting weight maintenance among overweight and obese Hispanic children in a rural practice. Child Obes. 2015;11(4):355‐363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dionne‐Odom JN, Taylor R, Rocque G, et al. Adapting an early palliative care intervention to family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer in the Rural Deep South: a qualitative formative evaluation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(6):1519‐1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hendricks BA, Lofton C, Azuero A, et al. The project ENABLE Cornerstone randomized pilot trial: protocol for lay navigator‐led early palliative care for African‐American and rural advanced cancer family caregivers. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2019;16:100485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brockie T, Azar K, Wallen G, O'Hanlon Solis M, Adams K, Kub J. A conceptual model for establishing collaborative partnerships between universities and Native American communities. Nurse Res. 2019;27(1):27‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brockie TN, Dana‐Sacco G, Wallen GR, Wilcox HC, Campbell JC. The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to PTSD, depression, poly‐drug use and suicide attempt in reservation‐based native American adolescents and young adults. Am J Community Psychol. 2015;55(3‐4):411‐421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lowe J, Riggs C, Henson J. Principles for establishing trust when developing a substance abuse intervention with a native American community. Creat Nurs. 2011;17(2):68‐73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lowe J, Wimbish‐Cirilo R. The use of talking circles to describe a native American transcultural caring immersion experience. J Holist Nurs. 2016;34(3):280‐290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Probst JC, Laditka JN, Laditka SB. Association between community health center and rural health clinic presence and county‐level hospitalization rates for ambulatory care sensitive conditions: an analysis across eight US states. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Probst JC, Samuels ME, Hussey JR, Berry DE, Ricketts TC. Economic impact of hospital closure on small rural counties, 1984 to 1988: demonstration of a comparative analysis approach. J Rural Health. 1999;15(4):375‐390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Westergaard RP, Ambrose BK, Mehta SH, Kirk GD. Provider and clinic‐level correlates of deferring antiretroviral therapy for people who inject drugs: a survey of North American HIV providers. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Westergaard RP, Beach MC, Saha S, Jacobs EA. Racial/ethnic differences in trust in health care: HIV conspiracy beliefs and vaccine research participation. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):140‐146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shaw JL, Beans JA, Comtois KA, Hiratsuka VY. Lived experiences of suicide risk and resilience among Alaska Native and American Indian People. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(20):3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shaw JL, Brown J, Khan B, Mau MK, Dillard D. Roadblocks and turning points: a qualitative study of American Indian/Alaska Native adults with type 2 diabetes. J Community Health. 2013;38(1):86‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Elliott A, White Hat ER, Angal J, Grey Owl V, Puumala SE, Baete Kenyon DY. Fostering social determinants of health transdisciplinary research: the Collaborative Research Center for American Indian Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gohlke JM, Thomas R, Woodward A, et al. Estimating the global public health implications of electricity and coal consumption. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(6):821‐826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Scull TM, Malik CV. Media literacy education approach to teaching adolescents comprehensive sexual health education. Janis B. 2014;6(1):1‐14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Angal J, Petersen JM, Tobacco D, Elliott AJ. Prenatal alcohol in SIDS and stillbirth network. Ethics review for a multi‐site project involving tribal nations in the Northern Plains. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2016;11(2):91‐96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. National Institute for Nursing Research . State of Rural Health Disparities: Research Gaps and Recommendations. Executive Summary. 2018. Accessed January 15, 2020. https://www.ninr.nih.gov/sites/files/docs/2018‐State‐of‐Rural‐Health‐Disparities‐NINR‐Workshop‐508c.pdf

- 33. Courtney J. H.R.748 ‐ 116th Congress (2019–2020): CARES Act . 2020. Accessed October 23, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th‐congress/house‐bill/748

- 34. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19): Information for NIH Applicants and Recipients of NIH Funding | grants.nih.gov. Accessed June 22, 2020. https://grants.nih.gov/policy/natural‐disasters/corona‐virus.htm

- 35. National Institutes of Health . NIH to Assess and Expand COVID‐19 Testing for Underserved Communities. 2020. Accessed October 23, 2020. https://www.nih.gov/news‐events/news‐releases/nih‐assess‐expand‐covid‐19‐testing‐underserved‐communities