ABSTRACT

Aim

To review the evidence on safety of maintaining family integrated care practices and the effects of restricting parental participation in neonatal care during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic.

Methods

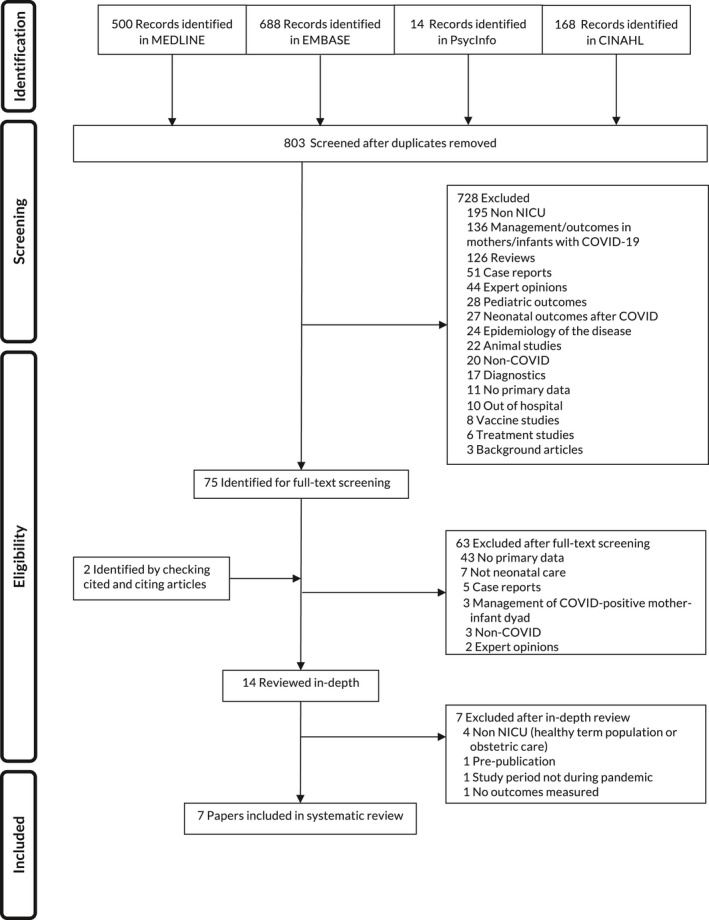

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL databases were searched from inception to the 14th of October 2020. Records were included if they reported scientific, empirical research (qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods) on the effects of restricting or promoting family integrated care practices for parents of hospitalised neonates during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. Two authors independently screened abstracts, appraised study quality and extracted study and outcome data.

Results

We retrieved 803 publications and assessed 75 full‐text articles. Seven studies were included, reporting data on 854 healthcare professionals, 442 parents, 364 neonates and 26 other family members, within 286 neonatal units globally. The pandemic response resulted in significant changes in neonatal unit policies and restricting parents' access and participation in neonatal care. Breastfeeding, parental bonding, participation in caregiving, parental mental health and staff stress were negatively impacted.

Conclusion

This review highlights that SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic‐related hospital restrictions had adverse effects on care delivery and outcomes for neonates, families and staff. Recommendations for restoring essential family integrated care practices are discussed.

Keywords: family integrated care, family centred care, SARS‐CoV‐2, COVID‐19, neonatal, parent

Abbreviations

- COVID‐19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- FCC

Family centred care

- FICare

Family Integrated Care

- GA

Gestational age

- GRIPP‐2

Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public

- HCP

Healthcare professional

- NA

Not available

- NICU

Neonatal intensive care unit

- PPE

Personal protective equipment

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analysis

- QATSDD

Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs

- SARS‐CoV‐2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Key Notes.

During the pandemic, hospitals attempted to limit viral spread by restricting access to all but essential staff of inpatient areas. The benefits of parental caregiving in neonatal intensive care were not considered separately.

This systematic review of the published evidence found that the policy changes adversely impacted parents, infants and healthcare staff.

We provide guidelines to safely re‐establish parents as essential care providers during a pandemic.

1. INTRODUCTION

At the beginning of 2020, as a consequence of the pandemic and paucity of knowledge around SARS‐CoV‐2, hospitals and healthcare systems acted swiftly to put in place measures intended to reduce viral spread. 1 , 2 Many decisions were made emergently with little evidence to support them. Hospitals often applied a ‘one‐size‐fits‐all’ approach without regard to the particular contexts of different patient care areas. Much of the focus was on adult care. The essential and irreplaceable benefits of parental caregiving in neonatal and paediatric services were often not considered.

Despite longstanding public pledges by healthcare organisations to deliver family‐centred care, families were often not involved in the development of COVID‐19 pandemic response plans. 3 Families had restricted access to their loved ones; digital platforms were installed to replace personal contact between patients and their families; patients died without their family at the bedside, and person‐ and family‐centred care practices worldwide were constrained. 4 Some hospitals made exceptions for neonatal and paediatric units. 3 However, many neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) restricted parental access to one parent (usually the mother) and, depending on the region or clinical circumstances, significantly restricted the amount of time parents could spend with their infant (sometimes as low as 5–15 min per day). 3 , 5 The one‐parent policy left fathers/partners unable to see their infant, often for many weeks.

Restricting parents' access to their infant can have detrimental effects on parent‐infant bonding, parental mental health and breastfeeding and this collateral damage is known to have long‐term adverse effects. 6 The pandemic‐related restrictions on family participation in caregiving for small and sick newborns abandon progress made over decades to achieve zero‐separation between parents and their infants, even (or especially) for the most critically ill newborns. Pandemic‐related practices restricting parental presence and participation in neonatal care all contravene evidence and best practice guidance and standards, for example, in the European Standards of Care for Newborn Health and the World Health Organisation Survive and Thrive report. 7 , 8 To achieve the standards, NICUs are expected to actively welcome and engage parents in the care of their newborn, facilitate 24/7 parental presence, encourage early skin‐to‐skin contact and provide breastfeeding support, along with other family centred care/family integrated care practices. These best practices and standards apply across levels of care and high‐ or low‐income country status.

Since the start of the pandemic, evidence has emerged that SARS‐CoV‐2 affects the neonatal/ paediatric population differently than adults and that there is a low risk of vertical and horizontal transmission in the neonatal period. 9 , 10 , 11 Systematic reviews and guidelines have already provided guidance on the treatment and management of COVID‐19 positive mothers and their infants. 5 However, we found no review of the evidence regarding the restrictions placed on parental presence and participation in neonatal care.

Therefore, we conducted a systematic review of the evidence on the safety of maintaining family integrated care practices during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic and the effects of restricting parental access to neonatal care. Our primary aim was to review published studies reporting on family integrated care/family centred care practices implemented or restricted due to hospital policies affecting families during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic and the effect those policies have had on families and healthcare professionals. Following our critique of the evidence, we propose evidence‐based recommendations to support parental presence and family integrated care during the COVID‐19 or any future public health emergencies.

2. METHODS

For this systematic review, we used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analysis (PRISMA) guidelines 12 and the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP‐2) short form. 13

2.1. Search strategy, study selection, data collection and risk of bias

A medical information specialist, experienced in systematic reviews, searched the following databases from inception to the 14th of October 2020: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO (through the OVID interface). We used both controlled terms (ie MeSH‐terms in MEDLINE) and free text terms related to infants, families and SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID‐19. See Appendix S1, for full search strategies. There were no restrictions on language, date, study type or publication status. We cross‐checked reference lists and cited articles of identified relevant papers. Records were considered eligible for inclusion if they reported on scientific, empirical research (qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods) reporting the effects of restricting or promoting family integrated care practices for parents, or the needs of parents of hospitalised infants during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. Two researchers (NvV and AD) screened abstracts and assessed full‐text articles for inclusion. Discrepancies were resolved via discussion within the research team. We used the most complete and recent paper if multiple papers assessed the same (sub)population.

Data extraction included meta‐data (eg authorship, publication year); methodological aspects (eg study design, setting, sample size, family integrated care practices, measurement instruments, analytic approach); and outcomes (e.g. qualitative quotes and interpretations, statistical evidence). The prespecified outcomes on the hospital level included: parental presence on units, skin‐to‐skin care, degree of family centred care (FCC), degree of family integrated care (FICare), breastfeeding rates and rooming‐in rates. On the family level, outcomes included parent infection with SARS‐CoV‐2, stress, satisfaction, participation, self‐efficacy, depression, anxiety, post‐traumatic stress, empowerment and parent‐infant bonding during the infant's hospital stay.

2.2. Risk of bias

As we anticipated diverse study designs, we used the 16‐item Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs (QATSDD) to assess study quality. 14 This tool has good reliability and validity across study domains and is suited for the assessment of qualitative, quantitative and mixed‐methods studies. 15 Quality of each record was independently and blind from each other assessed by two researchers (NvV and LF).

3. RESULTS

We identified a total of 803 articles with our search strategy. After screening titles and abstracts, 75 full‐text articles were assessed (see Figure 1). Subsequently, 7 studies were included concerning data on 854 healthcare professionals (HCPs), 442 parents (66 fathers), 364 infants and 26 other family members, within 286 neonatal units. Studies were conducted globally (n = 2 studies 16 , 17 ), in the USA (n = 3 studies 17 , 18 , 19 ) in the UK (n = 2 studies 19 , 20 ), one in China 21 and one in Italy. 22 Two studies used mixed‐methods, 16 , 19 4 were quantitative studies, 17 , 18 , 20 , 22 and 1 was a qualitative study. 21 The most common study design was a cross‐sectional survey. See Table 1 for details of the studies included.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram. COVID, coronavirus disease; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| First author | Region | Study design | Period | Population of interest | Exposure/intervention due to COVID | Outcomes measured in | Outcome (quantitative) | Outcome (qualitative) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | Infants | HCP | ||||||||

| Bainter 18 | USA | Informal survey | Unknown | 19 family partners, 28 clinicians | Respondents were asked to reflect on the degree to which their centres were inclusive of families in several roles: at the bedside in the care of their babies, as members of quality improvement teams, and as participants in decision‐making processes, both prior to and during the COVID‐19 outbreak. | Y | ‐ | Y | ‐ |

Recent restrictions on in‐person participation at the bedside and reinstated ‘visiting hours’ have been the most abrupt culture change due to COVID‐19, overriding family preferences and peer support among other aspects of family‐centred care. Family Partners and clinicians surveyed felt that a major concern was the lack of meaningful, consistent communication with families, in relation to baby care, as well as in relation to policy changes in the COVID‐19 environment. Other chief concerns expressed in the survey were the restriction of family access to the NICU and participation in daily care, and decreased overall family support. Both Family Partners and clinicians shared a concern about the lack of family representation in policy and decision‐making processes. |

| Brown 20 | UK | Cross‐sectional survey | for 4 weeks during May–June 2020 |

1219 mothers, babies aged 0–12 months with breastfeeding at least once during COVID‐19. 724 gave birth during pandemic and 103 mothers had babies in NICU during pandemic |

Overall, 7.8% stated they were not supported to have skin‐to‐skin, 4.6% were not encouraged to breastfeed as soon as possible after birth, 24.6% were not given information on expressing milk, and 21.2% stated they received no breastfeeding support in hospitals. Participants who had a baby in neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) were asked whether they could visit their baby. |

Y | Y | ‐ |

The most common reason for BF cessation was insufficient professional support followed by physical issues such as difficulties with latch, exhaustion, insufficient milk and pain. Of the 103 mothers who had a baby in NICU, 19.4% (n = 20) were told they could not visit their baby in NICU. Not being able to visit their baby in NICU was associated with no longer breastfeeding (χ 2 = 44.645, p = 0.000). At the time of survey completion, 80.0% who were told they could not visit their baby were no longer breastfeeding compared with 9.6% of those who could. |

‐ |

| Cavicchiolo 22 | Italy (Veneto, red zone) | Cohort surveillance study | 21 February–21 April 2020 |

114 parents and 112 HCPs, (total of 6726 triage procedures) with 65 infants, 1 unit |

To avoid overcrowding, parental visits were restricted to 1 h/day, and only one parent per baby at scheduled times. All parents were asked to wear masks, gloves and disposable clothing. All close contacts, such as kangaroo mother care and holding the baby, were suspended. A video calling service was activated for parents in quarantine who could not visit their children. Written educational material was given to HCPs and parents to help prevent viral transmission. (a) parental triage on arrival at the neonatal ward; (b) universal testing with nasopharyngeal swabs and blood testing for SARS‐ CoV‐2 IgM and IgG antibodies; (c) use of continuous personal protective equipment at the NICU by parents and staff |

Y | Y | Y |

75 admitted newborns, none were tested positive. 2 Parents asked for psychological support. No other psychological outcomes were measured. 2.2% tested positive (3 healthcare providers and 2 parents) |

‐ |

| Darcy Mahoney 17 | Globally | Cross‐sectional survey of units | April 21 to 30, 2020 | 277 units | Hospital and NICU entry policies began to change in January 2020 with a rapid increase in hospitals adopting policy changes throughout March, the majority prior to the issuance of CDC guidance. Overall, 184 (66%) NICUs reported that their new policies during the COVID‐19 pandemic were broadly more restrictive than the customary policies implemented during the winter influenza/respiratory syncytial virus season. | ‐ | ‐ | Y |

Single‐family room design NICUs best preserved 24/7 parental presence after the emergence of COVID‐19 (single‐family room 65%, hybrid‐design 57%, open bay design 45%, p = 0.018). In all, 120 (43%) NICUs reported reductions in therapy services, lactation medicine, and/or social work support. NICU policies preserving 24/7 parental presence decreased (83–53%, p < 0.001) and of preserving full parental participation in rounds fell (71–32%, p < 0.001). |

‐ |

| Fan 21 | China | Qualitative, interview study | Unknown | 14 parents (8 fathers, 6 mothers), 12/14 preterm infants, mean birthweight: 2312 g, 1 unit |

NA No data on before practices |

Y | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 5 themes were present for psychological needs of parents: urgent demand for timely up‐to‐date information of the children's condition, need for psychological and emotional support, reducing the inconvenience caused by the epidemic outbreak, demand for protective information after discharge, demand for financial support. |

| Muniraman 19 | UK and USA | Cross‐sectional survey of parents | 1 May 2020–21 August 2020 |

Parents of infants in the NICU (7 tertiary NICUs) 153 mothers, 58 fathers and 5 grandparents. 1 sibling and 1 guardian. 66% preterm infants 45% length stay <1 week |

Access limited to a single visitor with no restrictions on duration was the most frequently reported policy; 140/217 (63%). Visitation policies were perceived as being restrictive by 62% (138/219) of the respondents with 37% (80/216) reporting being able to visit less often than desired |

Y | ‐ | ‐ |

41% (78/191) reporting being unable to bond enough and 27% (51/191) reporting not being able to participate in their baby's daily care. Mild to severe impact on breastfeeding was reported by 36% (75/209) of respondents. Stricter policies had a higher impact on families and were significantly associated with a lack of bonding time, inability to participate in care and an adverse impact on breast feeding. |

“I will remember this for the rest of my life. I will also remember the kindness of the staff but at 18 h old I was told my baby might die and I had to beg to see him because I had already had my 2 h. How is that ok???” Felt like my baby was not mine and I was asking permission from the nurses. Also has made me feel resentful towards [my] husband as all the emotional burden of a child in NICU fell upon myself; The visiting times force a choice between cuddles and learning how to tube feed etc. Consequently this has left me feeling like I don't take good care of my baby. Not acceptable for a postnatal women. I would imagine PND [postnatal depression] will be very high in this epidemic. I have found the visiting restrictions very tough and would love for nothing more than myself and my partner to be able to see our child together. It has been an extremely tough few weeks emotionally and I wish we could support each other in NICU together and be prepared for discharge. |

| Semaan 16 | Global | Cross‐sectional + thematic analysis with surveys | 24 March and 10 April 2020 |

714 maternal and newborn HCPs; Most were obstetricians/gynaecologists or midwives (38% and 35%, respectively) |

Facility‐level responses to COVID‐19 were more common in high‐income countries compared to low‐/middle‐income countries. | ‐ | ‐ | Y |

90% of respondents reported higher levels of stress Stress levels somewhat higher in 52% and substantially higher in 38% Most were knowledgeable about hospital COVID‐guidelines but up to 80% had some areas of concern or lack of clarity. |

Respondents perceived the lack of COVID‐19 symptom screening and testing as threats to staff and patient safety. There were additional concerns that PPE disrupts clear communication with patients; Respondents were concerned over uncertain impacts of reduced contacts on the quality of care. Three respondents from India noted that infant vaccination schedules were disrupted or postponed. HCPs feared that changes in standards of care would lead to poor health outcomes among women and newborns and subsequently to the loss of achieved progress. |

|

Total: 364 Infants 442 Parents (66 fathers) 854 Healthcare professionals 19 Family partners 5 Grandparents 1 Siblings 1 Guardians 286 Units |

||||||||||

Abbreviations: COVID, coronavirus disease; GA, gestational age; HCP, healthcare professional; NA, not available; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PPE, personal protective equipment; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America; Y, Yes.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Quality of the studies was moderate. Most studies lacked an explicit theoretical framework, power calculations to assess outcomes, assessment of reliability and validity of surveys, and involvement of stakeholders in research and design (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Quality assessment of papers (QATSDD)

| Author (ref) | Study design | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bainter 18 | Qualitative | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 8/42 | 19% |

| Brown 20 | Quantitative | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | NA | 2 | 0 | NA | 0 | 3 | 20/42 | 48% |

| Cavicchiolo 22 | Quantitative | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | NA | 2 | 0 | NA | 0 | 2 | 26/42 | 62% |

| Darcy Mahoney 17 | Quantitative | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | NA | 2 | 2 | NA | 0 | 2 | 20/42 | 48% |

| Fan 21 | Qualitative | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 15/42 | 36% |

| Muniraman 19 | Mixed | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 20/48 | 42% |

|

Semaan 16 |

Mixed | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 27/48 | 56% |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; QATSDD, Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Design.

Scores range from 0–3.

Item 1: Explicit theoretical framework

Item 2: Statement of aims/objectives in main report

Item 3: Clear description of research setting

Item 4: Evidence of sample size considered in terms of analysis

Item 5: Representative sample of target group of a reasonable size

Item 6: Description of procedure for data collection

Item 7: Rationale for choice of data collection tool(s)

Item 8: Detailed recruitment data

Item 9: Statistical assessment of reliability and validity of measurement tool(s) (Quantitative studies only)

Item 10: Fit between research question and method of data collection (Quantitative studies only)

Item 11: Fit between research question and format and content of data collection tool, for example interview schedule (Qualitative studies only)

Item 12: Fit between research question and method of analysis (Quantitative studies only)

Item 13: Good justification for analytic method selected

Item 14: Assessment of reliability of analytic process (Qualitative studies only)

Item 15: Evidence of user involvement in design

Item 16: Strengths and limitations critically discussed

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

3.1. Pandemic response impact on NICUs, infection rates, infants, family and staff

The limited research on the pandemic responses of hospitals and NICUs revealed significant changes in the dimensions that were investigated: NICU operations, SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission, impact on breastfeeding, parental bonding, parental participation in caregiving, parental mental health and staff stress. The findings are described in detail below and in Table 1.

3.1.1. Changes in NICU policies affecting parent and family access and patient care

Changes in overall hospital entry screening policies became widespread during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic and included significant increases in physical temperature checks, and triage/screening questions regarding travel history, cough, fever or loss of smell for hospital entry. 17 NICUs revoked parental 24‐h access and as a result, parents were unable to attend daily rounds and be involved in usual care tasks. 17 Some hospitals completely refused entry to parents during the pandemic, even if their infant was in extremis. 17 , 19 , 21 Most often the hospital policies evolved to permit one parent at a time to be present with the infant. However, the support for prolonged parental presence (rest space and food) was significantly reduced 17 , 20 and there was a significant reduction in therapy services and lactation support. 17

In addition to the loss of parent and family participation in care, the pandemic‐related restrictions significantly affected staffing and further impacted patient care. Forty‐three per cent of units surveyed 17 reported a decrease in support staff due to policies restricting their presence or a redeployment of staff, resulting in infants receiving less input from the multidisciplinary therapist team and non‐urgent procedures being delayed. 17

3.1.2. Risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission on NICU amongst healthcare professionals and parents/ hospital acquired infection in neonates

To date, there are no reports of in‐hospital transmission between neonatal patients despite preterm newborns being considered a population vulnerable to respiratory viruses. We found one report describing in detail the prevalence of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in an Italian NICU during the high prevalence period of the pandemic with the use of universal screening of HCPs and families. 22 Parents were screened on arrival to the unit and parental presence was restricted in time and to only 1 parent per baby. Parents, HCPs and infants were screened weekly for COVID‐19 with nasopharyngeal swabs (rt‐PCR) and SARS‐CoV‐2 IgM and IgG antibody tests. Infants born to COVID‐19 positive mothers were kept isolated in closed incubators and parents were not allowed to enter the unit until deemed non‐infectious. During this period none of the admitted newborns tested positive (0/75) on nasopharyngeal swabs or antibody tests, including those being born to mothers with suspected/confirmed COVID‐19 (n = 3). Three parents were identified with flu‐like symptoms, but tested negative. Of those screened (112 HCPs and 114 parents) five persons tested positive (2.2%), reflecting the same positivity rate as in the community at the time. All were asymptomatic and 3 were HCPs. Of note, during this time all close contact such as skin‐to‐skin care and holding the baby were suspended in the unit.

3.1.3. Impact on breastfeeding

The research to date on the impact of the pandemic on breastfeeding outcomes for NICU infants and mothers' breastfeeding experiences describes a possible negative affect for both term mother and infant dyads as for preterm infants in a NICU environment. Mothers frequently reported not being supported to provide skin‐to‐skin care to their infant or encouraged to breastfeed as soon as possible after birth. 19 They reported not receiving enough information on expressing breastmilk or breastfeeding support. 19 , 20

In term infants, a report from the UK based on a parent survey of 1219 mothers, indicated that many who stopped breastfeeding felt that the lack of face‐to face support and concerns about safety of breastfeeding during the pandemic contributed to the cessation of breastfeeding earlier than planned. As part of this larger study of breastfeeding, survey participants whose infants were admitted to the NICU (n = 103/1219) were asked about parental access and support. 20 Of this subsample, 19.4% (20/103) reported they were not permitted to see their infant in the NICU. This separation was detrimental for breastfeeding and associated with 80% of the mothers (16/20) no longer breastfeeding at the time of the survey. Other reports in the NICU population also indicate that breastfeeding was negatively impacted by the parent‐infant separation and the lack of lactation support both in hospital and on discharge home. 17 , 19

3.1.4. Impact on parent‐infant bonding and parent participation in care

Parents reported that the restrictive policies on their NICU access limited their ability to bond with their infant or to participate in their infant's care or NICU daily rounds. 17 , 19 , 20 Parents also expressed concerns that they received insufficient information and updates about their infants due to the restrictions. NICUs that had single‐family room designs were better prepared to support parents to be with their infant during the pandemic and to enable them to participate in daily rounds. 17 In addition, due to lack of staff support coupled with imposed restrictions on time with their infant, parents reported that they sometimes had to choose between learning technical skills from nurses (eg tube feeding) versus holding and bonding with their infant. Parents also reported that wearing a face mask affected bonding with their infant and depersonalised interactions with staff. 19

3.1.5. Impact on parental mental health

In the early phase of the pandemic, 14 parents of infants in a NICU in China, described difficulties in obtaining up‐to‐date information on their children's condition, and unmet needs for psychological and emotional support. They also described challenges with transportation or work commitments, and concerns about how to protect their infants or deal with medical expenses after discharge. 21

Other survey studies documented reduced psychosocial support for parents related to hospital pandemic restrictions. 17 , 18 Parents reported concerns about not being able to bring siblings and grandparents to the NICU to provide them support and expressed concerns surrounding not being able to spend time together as a family. 19 Psychological outcomes in parents were often not assessed after restrictions were put in place. 22 Parents reported impact on their mental health if they were not able to be with their infant. 19

3.1.6. Impact on healthcare professionals

HCPs during the pandemic reported high level of stress and anxiety. 16 , 17 HCPs expressed a fear of nosocomial acquisition either due to lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) and/or COVID‐symptom screening. In some instances, PPE supplies were prioritised to adult wards caring for COVID‐19 positive patients in contrast to maternity wards and NICUs. 16 Shortages of qualified HCPs, increased workload and frequent schedule changes due to redeployment or COVID‐19 quarantine/illness have also been reported as sources of HCP stress. 16 , 17 NICU staff also expressed concerns regarding the impact of the policy restrictions on family presence and participation on the quality of infant care.

4. DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we summarise the emerging research and importance of family integrated care practices during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. The findings indicate that parent and family access and participation in infant caregiving has been severely restricted and has led to adverse effects for infants, families and HCPs. Patients and their families must be supported to maintain physical and emotional contact under all circumstances. While infection control measures need to be taken, parents must be included as partners in their infant's care and establish safe family presence and shared care delivery. 23

The severe restrictions imposed in hospital perinatal settings, including the NICU, have increased parent‐infant and parent‐parent separation, and this together with the anxiety concerning the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic was found to be associated with acute distress and may worsen long‐term mental health, for this already high‐risk population. While telemedicine/video systems were implemented and used in many places 17 and online parent support groups were created, 24 they are not able to replace the benefit of parents' physical contact, and efficacy remains to be elucidated. One study reported on the use of a video‐messaging service for parents to improve engagement but did not include the evaluation during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 25

Our systematic review indicated that most often, infections came from HCPs and not from the parents. 22 Rather than banning parents from the NICU, alternative strategies to preventing infection may be more effective, such as universal screening to identify asymptomatic positive cases amongst HCPs and parents and providing appropriate PPE. 22 This finding is supported by reports in other healthcare environments 26 where overall transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2 in the settings of universal masking is rare and that unmasked exposure to other HCPs is a source of hospital outbreaks. It is absolutely essential that when parents are considered part of the care team, that they have the same access to screening, testing, PPE and adequate well‐ventilated space allowing physical distancing for breaks and meals.

Over the course of 2020, parent‐led advocacy groups have been outspoken about the harms and risks to infants and families caused by hospitals restricting family presence and contact. 27 , 28 More recently, professional parent organisations across the globe have joined the call to re‐establish parents as essential partners in care during the pandemic. 18 , 23 , 29 These calls have been largely unheard by hospitals and health systems that continue to enforce restrictive policies. Moreover, parent and family advisors have not been included when changes have been made to hospital policies during this pandemic, 3 despite prior inclusion in NICU and hospital decision‐making. This may have appeared expedient at the outset, but now with pandemic fatigue setting in and public health messaging about the disease changing almost daily, it is more paramount than ever that we involve these key stakeholders in decision‐making, communication and support for NICU families. 18

4.1. Strengths and limitations

We found only a limited number of studies of the impact of the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic on families with infants in NICUs and no data on longer term consequences related to increased separation. Therefore, we regard this evidence as preliminary. There is an urgent need to continue to follow infants and families exposed to these severe restrictions during the pandemic to assess long‐term impact on physical and mental health and development. A strength of this study is that we have included parents of NICU infants as part of our study team and have reviewed the findings within our multidisciplinary team of HCPs adding to the validity and importance of this review for all stakeholders. We did not assess the “grey” literature for this review. Newspapers, social media, blogs (etc) also discussed the impact of restrictions of hospital policy entrance for family in the (early phases of the) epidemic. 30

5. CONCLUSION

Hospitals responded quickly to install restrictive measures within neonatal care during the COVID‐19 pandemic, often without consulting parents and assessing the long‐term impact on parents and their babies. Our review highlights that the described restrictions have increased parent‐infant separation, reduced the chance of successful breastfeeding, and together with anxiety concerning the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic may worsen the long‐term mental health damage additionally to the high risk associated with the perinatal period and NICU journey.

It is time to (re)instate families as full partners in neonatal care delivery and to safely practice evidence‐based family centred and family integrated care in all (neonatal) care settings despite the current pandemic and beyond.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr van Veenendaal and dr Deierl equally contributed to the manuscript. They conceptualised and designed the study, performed the systematic literature search, collected data, performed the data analyses, performed quality assessment of studies, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Mrs Baccchini contributed to contextualising and reorganising the findings, critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr O’Brien and professor Franck equally contributed to the manuscript. They conceptualised and designed the study, contributed to title and abstract screening, performed quality assessment of studies and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All International Steering Committee for Family Integrated Care group members revised and reviewed the manuscript. All authors accept full responsibility for the work, and the conduct of the study had full access to the data and controlled the decision to publish. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

RECOMMENDATIONS TO SUPPORT PARENTAL PRESENCE AND FAMILY INTEGRATED CARE DURING COVID‐19 AND BEYOND

We as the International Steering Committee for Family Integrated Care make the following recommendations. These should be supported to enable both parents unlimited access and participation in care of their infant(s) for the duration of their infant's stay in hospital, ensuring that parents are supported to meet the same screening criteria as used for staff.

-

●

A birth partner/parent should be supported to attend the delivery of their infant in the labour ward, unless they are symptomatic, or have been advised to self‐isolate or quarantine.

-

●

Mothers and infants should remain together, even if mother is COVID‐19 positive; they should still be able to practice skin‐to‐skin care and rooming‐in day and night especially during establishment of breastfeeding.

-

●

Both parents should be with their infant on the neonatal unit and postnatal ward, unless they are symptomatic or have been advised or required to self‐isolate or quarantine. Use of verbal/written symptom checklist at the entrance to the unit/hospital as is required by staff is suggested.

-

●

Parents should be provided with the same protection as staff, for example, surgical face masks, or be able to bring their own face masks. Parents need information and education about when masks are required, how to wear them, how to wash if cloth masks are used, and where they would be able to purchase surgical masks if they are not supplied by the hospital.

-

●

All parents and staff should be educated and apply appropriate hand‐ and respiratory hygiene measures within the hospital and the home environment.

-

●

Physical distancing advice should be supported, and if not possible, parents should be provided with the same infection control precautions, education and advice as staff. If available, parents should have access to regular testing (PCR or antigen testing) in the same way as staff.

-

●

Parents should be included in ward rounds and be part of holistic family care, including education and psychosocial support.

-

●

If physical distancing within the unit is not possible, one parent at a time should be involved in their infant's care without time restrictions; this enables parents to take turns. There is no rationale for the restriction of time or the restriction to one person alone from the same household.

-

●

Parents and staff should adhere to physical distancing policies in the neonatal unit or postnatal ward, including in communal areas, such as parents' waiting rooms and reception areas of the neonatal units.

-

●

Continual wearing of face masks by parents could potentially impact negatively upon infant development and parent‐infant bonding and may hinder hearing‐impaired staff and parents. NICU's should consider the use of approved clear masks for this population. Where a safe physical distance can be maintained between staff and families, parents should be supported to care for their infant at the cot‐side without wearing a face covering.

-

●

Where possible, dedicated space should be available for parents to safely eat and rest, on the neonatal unit or nearby so to be close to their infant.

-

●

Neonatal teams should make every effort to provide additional measures to support parental presence during COVID‐19, including the provision of face masks, accommodation, meals, parking and transport.

-

●

Appropriate technological support using video calling and Apps should not be used to replace parental presence in the neonatal unit but can be used to support parental involvement and communication with staff at those times when parents cannot be with their infant.

-

●

For babies critically ill or receiving palliative or end‐of‐life care, everything possible should be done to achieve parental presence and participation in care, even for SARS‐CoV‐2 positive parents.

-

●

As vaccines become more available, parents as primary caregivers, members of the neonatal team should be given early access to vaccination along with healthcare professionals in the neonatal intensive care units to reduce risk of cross transmission.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

Appendix S2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank B. Berenschot and C. den Haan from the Library of OLVG, Amsterdam, The Netherlands for setting up the search strategy and acquiring full texts.

Nicole R. van Veenendaal and Aniko Deierl Co‐first authors.

Karel O’Brien and Linda S. Franck Co‐senior authors.

[Correction added on [date], after first online publication: The key notes have been corrected in this version.]

REFERENCES

- 1. Jerry J, O’Regan E, O’Sullivan L, Lynch M, Brady D. Do established infection prevention and control measures prevent spread of SARS‐CoV‐2 to the hospital environment beyond the patient room? J Hosp Infect. 2020;105:589‐592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person‐to‐person transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2 and COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2020;395:1973‐1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Franck L. COVID‐19 Hospital Restrictions ‐ Surveying Impact on Patient‐ and Family‐Centered Care [Internet]. https://pretermbirthca.ucsf.edu/covid‐19‐hospital‐restrictions‐surveying‐impact‐patient‐and‐family‐centered‐care. Accessed July 3, 2020.

- 4. Wakam GK, Montgomery JR, Biesterveld BE, Brown CS. Not dying alone — modern compassionate care in the Covid‐19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lavizzari A, Klingenberg C, Profit J, et al. International comparison of guidelines for managing neonates at the early phase of the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. Pediatric Research. 2021;89:940‐951. 10.1038/s41390-020-0976-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bergman NJ. Birth practices: maternal‐neonate separation as a source of toxic stress. Birth Defects Res. 2019;111:1087‐1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. EFCNI . European Standards of Care for Newborn Health. 2018.

- 8. WHO (World Health Organization) . Survive and thrive: Transforming care for every small and sick newborn. 2019.

- 9. Milani GP, Bottino I, Rocchi A, et al. Frequency of children vs adults carrying severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 asymptomatically. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;175:193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fenizia C, Biasin M, Cetin I, et al. Analysis of SARS‐CoV‐2 vertical transmission during pregnancy. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaufman DA, Puopolo KM. Infants born to mothers with COVID‐19—making room for rooming‐in. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;175:240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ. 2017;j3453. 10.1136/bmj.j3453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sirriyeh R, Lawton R, Gardner P, Armitage G. Reviewing studies with diverse designs: the development and evaluation of a new tool. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:746‐752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fenton L, Lauckner H, Gilbert R. The QATSDD critical appraisal tool: comments and critiques. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21:1125‐1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Semaan A, Audet C, Huysmans E, et al. Voices from the frontline: findings from a thematic analysis of a rapid online global survey of maternal and newborn health professionals facing the COVID‐19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Heal. 2020;5:1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Darcy Mahoney A, White RD, Velasquez A, Barrett TS, Clark RH, Ahmad KA. Impact of restrictions on parental presence in neonatal intensive care units related to coronavirus disease 2019. J Perinatol. 2020;40:36‐46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bainter J, Fry M, Miller B, et al. Family presence in the NICU: constraints and opportunities in the COVID‐19 Era. Pediatr Nurs. 2020;46:256. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Muniraman H, Ali M, Cawley P, et al. Parental perceptions of the impact of neonatal unit visitation policies during COVID‐19 pandemic. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2020;4:e000899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brown A, Shenker N. Experiences of breastfeeding during COVID‐19: lessons for future practical and emotional support. Matern Child Nutr. 2020;17:1‐15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fan J, Zhou M, Wei L, Fu L, Zhang X, Shi Y. A qualitative study on the psychological needs of hospitalized newborns’ parents during covid‐19 outbreak in China. Iran J Pediatr. 2020;30:1‐7. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cavicchiolo ME, Trevisanuto D, Lolli E, et al. Universal screening of high‐risk neonates, parents, and staff at a neonatal intensive care unit during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179:1949‐1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Association of Women’s Health Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses, National Association of Neonatal Nurses, National Perinatal Association. Essential Care in the NICU during the COVID‐19 Pandemic. 2021.

- 24. Murray PD, Swanson JR. Visitation restrictions: is it right and how do we support families in the NICU during COVID‐19? J Perinatol. 2020;40:1576‐1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kirolos S, Sutcliffe L, Giatsi Clausen M, et al. Asynchronous video messaging promotes family involvement and mitigates separation in neonatal care. Arch Dis Child ‐ Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2020;106:172‐177.fetalneonatal‐2020‐319353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Richterman A, Meyerowitz EA, Cevik M. Hospital‐acquired SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: lessons for public health. JAMA ‐ J Am Med Assoc. 2020;324:2155‐2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Global Alliance for Newborn Care ‐ GLANCE [Internet]. https://www.glance‐network.org/. Accessed July 8, 2020.

- 28. Bliss . Bliss Statement: COVID‐19 and parental involvement on neonatal units. 2021.

- 29. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement . POLICY GUIDANCE FOR THE REINTEGRATION OF CAREGIVERS AS ESSENTIAL CARE PARTNERS Executive Summary and Report. 2020.

- 30. Digregorio S. Inside the pandemic‐era NICU, where one‐parent rules and strict visitation hours are upending the lives of critically ill babies. New York: New York Times; 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Appendix S2