Abstract

Background and purpose

To assess neurological manifestations and health‐related quality of life (QoL) 3 months after COVID‐19.

Methods

In this prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study we systematically evaluated neurological signs and diseases by detailed neurological examination and a predefined test battery assessing smelling disorders (16‐item Sniffin Sticks test), cognitive deficits (Montreal Cognitive Assessment), QoL (36‐item Short Form), and mental health (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist–5) 3 months after disease onset.

Results

Of 135 consecutive COVID‐19 patients, 31 (23%) required intensive care unit (ICU) care (severe), 72 (53%) were admitted to the regular ward (moderate), and 32 (24%) underwent outpatient care (mild) during acute disease. At the 3‐month follow‐up, 20 patients (15%) presented with one or more neurological syndromes that were not evident before COVID‐19. These included polyneuro/myopathy (n = 17, 13%) with one patient presenting with Guillain‐Barré syndrome, mild encephalopathy (n = 2, 2%), parkinsonism (n = 1, 1%), orthostatic hypotension (n = 1, 1%), and ischemic stroke (n = 1, 1%). Objective testing revealed hyposmia/anosmia in 57/127 (45%) patients at the 3‐month follow‐up. Self‐reported hyposmia/anosmia was lower (17%) at 3 months, however, improved when compared to the acute disease phase (44%; p < 0.001). At follow‐up, cognitive deficits were apparent in 23%, and QoL was impaired in 31%. Assessment of mental health revealed symptoms of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorders in 11%, 25%, and 11%, respectively.

Conclusions

Despite recovery from the acute infection, neurological symptoms were prevalent at the 3‐month follow‐up. Above all, smelling disorders were persistent in a large proportion of patients.

Keywords: COVID‐19, neuro‐COVID, neurologic manifestations, quality of life, SARS‐CoV‐2

Three months after COVID‐19, 20/135 patients (15%) presented with one or more neurological syndromes that were not evident before disease onset. Objective testing revealed hyposmia/anosmia in 45% of patients at the 3‐month follow‐up in comparison to 17% who reported hyposmia/anosmia. Cognitive deficits were apparent in 23%, quality of life was impaired in 31%, depression was found in 11%, anxiety in 25% and posttraumatic stress disorders in 11%.

INTRODUCTION

Reports of neurological manifestations associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) have emerged since the start of the outbreak in December 2019 in China [1]. So far, more than 40 distinct neurological symptoms and signs affecting the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) have been described [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9.

Neurological manifestations may result either directly from the virus or indirectly through antibody or immune‐mediated mechanisms [6]. In addition, systemic complications, including coagulation disorders, the cytokine storm, and multiple organ dysfunctions such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) may contribute to neuronal damage [5, 10, 11. The need for prolonged intensive care in severe patients leads to well‐known critical illness‐related complications involving the CNS and PNS, including intensive care unit (ICU) acquired weakness [12].

Little is known about long‐term neurological consequences of COVID‐19. In a cohort of 143 patients, prevalence rates of more than 5% were reported for headache, hyposmia, and myalgia 2 months after disease onset [13]. In another study of 60 selected patients who underwent advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques, more than 50% had neurological symptoms 3 months after disease onset [14].

Similarly, neuropsychiatric disorders including neurocognitive impairment, anxiety, and depressed mood become increasingly important in the long term, even in patients with mild disease [15, 16.

We conducted a 3‐month follow‐up study as part of an ongoing multicenter, prospective observational trial (CovILD [Development of Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) in Patients With Severe SARS‐CoV‐2 Infection]: NCT04416100) focusing on persistent and new neurological signs/symptoms and diseases. The main hypothesis was that neurological manifestations are prevalent at follow‐up. In addition, we aimed to quantify the impact of COVID‐19 on mental health and health‐related quality of life (QoL) 3 months after disease onset.

METHODS

Study design, setting, and participants

For this multicenter observational cohort study, consecutive COVID‐19 patients were prospectively enrolled during the acute phase of the disease. They were managed at three participating clinical trial sites, namely at the Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Innsbruck, Zams, and Muenster (all Tyrol, Austria). Innsbruck is a tertiary care center and Zams a secondary care center. Muenster is an acute rehabilitation facility but was refunctioned to a secondary care center during the pandemic. The diagnosis of COVID‐19 was based on a typical clinical presentation together with a positive reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) test from a nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab. General inclusion criteria consisted of (i) confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, (ii) hospitalization or outpatient management, and (iii) age ≥18 years. Out of 190 patients screened during the acute phase, 145 were included in the CovILD study. Reasons for nonparticipation were mainly logistic (e.g., tourists who left the country and individuals who lived too far away from the study center to attend regular follow‐up, n = 27) or refusal of consent (n = 18) [17]. A total of 135/145 patients agreed to participate in the neurological follow‐up 3 months after disease onset and were evaluated using a structured neurological assessment between April 2020 and September 2020. Patients who died during the acute phase were not included in this study, and the ICU mortality rate was 19% as reported elsewhere [18]. Importantly, the Tyrolean healthcare system was never overloaded, and all patients received full medical support [18].

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The conduct of the study was approved by the local ethics committee (Medical University of Innsbruck, EK Nr: 1103/2020) and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04416100). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients according to local regulations.

Study procedures and data collection

Clinical evaluation

Baseline was defined as the day of diagnosis by a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 test result. Six weeks and 3 months after laboratory‐confirmed diagnosis, all patients underwent a structured cardiopulmonary follow‐up [17]. Medical history, admission characteristics, hospital complications, and applied treatments were assessed in all patients. Selected patients were evaluated for neurological symptoms by neurological consultancy during the acute phase of the disease. All patients diagnosed with critical illness polyneuropathy/critical illness myopathy (CIP/CIM) were seen by neurologists during the acute care. A detailed neurological evaluation was performed by neurological consultants or junior neurologists under the supervision of consultants and was carried out at the 3‐month follow‐up. The neurological assessment consisted of a structured interview and standardized neurological examination. The 16‐item Sniffin’ Sticks test (SS‐16; Burghart Medizintechnik, Wedel, Germany) was used to assess olfactory function in all patients; the nasal chemosensory performance was evaluated using pen‐like odor‐dispensing devices for odor identification of 16 common odorants (multiple forced‐choice from four verbal items per test odorant) [19]. Hyposmia and anosmia were determined using cutoff levels of ≤12 and ≤8, respectively, as per manufacturer criteria.

Cognitive deficits were assessed with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), a screening test to estimate the severity of global cognitive impairment with subcategories reflecting the following cognitive domains: visuospatial–executive, naming, memory, attention, language, abstraction, and orientation [20]. Impairment was classified in patients scoring below 26/30 points. The MoCA was not performed in patients with language barrier or visual impairment (n = 11).

Outcome instruments

Multidimensional outcomes were assessed using five instruments measuring health‐related QoL, mental health, and functional outcome.

Health‐related QoL was evaluated with the 36‐item Short Form (SF‐36v2), a self‐report questionnaire rating the subjective health condition encompassing mental, physical, and social functioning [21]. The questionnaire provides scores of eight health domains. The total scores (physical component score [PCS] and mental component score [MCS]) range from 0 to 100 points each, with higher levels indicating a better health condition. Total scores below 40 are considered impaired according to norm‐based scoring.

Posttraumatic stress, depression, and anxiety were captured with the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist–5 (PCL‐5) [22] and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [23]. The PCL‐5 captures 20 symptoms each with 0 to 4 points, resulting in a total score of 0 to 80, with higher sums being indicative of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Scores >32 suggest a clinically relevant PTSD. The HADS measures levels of anxiety and depression during the last week. This score consists of an anxiety (HADS‐A) and depression (HADS‐D) subscale, each of which contains seven items scored from 0 to 3. Scores range from 0 to 21 in each subscale, with lower scores correlating with less intensive anxiety‐ and depression‐related symptoms. Scores >7 indicate mild disorder, >10 a clinically meaningful anxiety disorder or depression [24].

Self‐report questionnaires were returned by 98 (73%) patients and completely filled in by 90 patients, leaving eight with incomplete results.

Fatigue was assessed by self‐report and according to items 9e (Did you have a lot of energy?), 9g (Did you feel worn out?), and 9i (Did you feel tired?) in the SF‐36v2. Functional outcome was rated according to the Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOSE), an eight‐point scale, and the seven‐point modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are given in counts and percentages, continuous variables were summarized using univariate statistical measures including medians and interquartile ranges or means and standard deviations. All results are given for different disease severity groups defined by the management setting during the acute phase: (i) nonhospitalized (mild) patients, (ii) hospitalized (moderate) patients not requiring ICU admission, and (iii) (severe) COVID‐19 patients admitted to the ICU. Based on the data distribution (Kolmogorov‐Smirnov test and Shapiro‐Wilk test), parametric or nonparametric tests were applied. We used the χ2 or Kruskal‐Wallis test to assess for differences across severity grades. In the setting of a p value <0.05 indicating significantly different data distribution across severity groups, we performed Bonferroni‐corrected post hoc pairwise analyses using univariate generalized linear models (Table S1). To test for changes in symptoms between the acute disease course and at 3 months, the McNemar test was used. Missing data were excluded from analysis and indicated appropriately. We built a multivariate generalized linear model to assess factors associated with fatigue 3 months after COVID‐19. We included preselected variables with a p < 0.1 in univariate analysis (t test, Mann Whitney U, and χ2 test) and retained them if significant (p < 0.05). Preselected variables included age (p = 0.983), sex (p = 0.425), risk categories (p = 0.003), length of hospital days (p = 0.042), any neurological disease not diagnosed before COVID‐19 (p = 0.007), polyneuro/myopathy (p = 0.012), self‐reported hyposmia (p = 0.616), SS‐16 ≤ 12 (p = 0.046), PCL‐5 > 32 (p = 0.031), HADS‐A > 7 (p = 0.788), HADS‐D > 7 (p = 0.031), sleep disturbance (p < 0.001), forgetfulness (p = 0.212), and MoCA <26 (p = 0.356), all at the 3‐month follow‐up. A two‐sided p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 24.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Data

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request and by fulfilling data sharing regulations approved by the local ethics committee.

RESULTS

A total of 135 COVID‐19 patients underwent a structured neurological evaluation 102 (interquartile range [IQR], 91–110) days after disease onset. The median age was 56 (IQR, 48–68) years ranging from 19 to 87 years, with a predominance of male patients (61%). Young female patients had a significantly milder disease course without necessitating hospital admission (p < 0.001; Table S1). During the acute disease, 31 patients (23%) required ICU care for invasive or noninvasive respiratory support, 72 patients (53%) were admitted to the normal ward, and 32 patients (24%) underwent outpatient care. A total of 33 patients (24%) reported prediagnosed neurological disorders evaluated by a neurologist before COVID‐19 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographics, comorbidities, and therapy in 135 patients according to COVID‐19 severity

| All, n = 135 | Severe disease requiring ICU admission, n = 31, 23% | Moderate severity, hospitalization, non‐ICU, n = 72, 53% | Mild severity, outpatient, n = 32, 24% | p value* | Missing data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 56 (48–68) | 58 (53–65) | 61 (52–72) | 45 (35–55) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Sex, female | 53 (39) | 7 (23) | 24 (33) | 22 (69) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26 (23–29) | 26 (24–30) | 26 (24–29) | 25 (21–29) | 0.168 | 2 |

| Current smoking | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (4) | 1 (3) | 0.519 | 0 |

| Ex‐smoking | 54 (40) | 10 (32) | 36 (51) | 8 (25) | 0.028 | 1 |

| Pack‐years | 9 ± 17 | 6 ± 13 | 13 ± 20 | 2 ± 6 | 0.003 | 1 |

| Premedical history | ||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 54 (40) | 18 (58) | 34 (47) | 2 (6) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Arterial hypertension | 41 (30) | 15 (48) | 24 (33) | 2 (6) | 0.001 | 0 |

| Pulmonary disease | 25 (19) | 5 (16) | 14 (19) | 6 (19) | 0.923 | 0 |

| Endocrinological disease | 58 (43) | 16 (52) | 35 (49) | 7 (22) | 0.021 | 0 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 25 (19) | 5 (16) | 19 (26) | 1 (3) | 0.017 | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus II | 24 (18) | 8 (26) | 15 (21) | 1 (3) | 0.038 | 0 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 9 (7) | 5 (16) | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.032 | 0 |

| Chronic liver disease | 7 (5) | 3 (10) | 3 (4) | 1 (3) | 0.427 | 0 |

| Malignancy | 16 (12) | 3 (10) | 11 (15) | 2 (6) | 0.385 | 0 |

| Immunological deficiency | 9 (7) | 6 (19) | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 0.005 | 0 |

| Preexisting neurological diseases | ||||||

| None | 102 (76) | 24 (77) | 52 (72) | 26 (81) | 0.591 | 0 |

| Stroke | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.644 | 0 |

| Parkinsonism | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ··· | 0 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ··· | 0 |

| Motor neuron disease | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ··· | 0 |

| Polyneuropathy | 7 (5) | 1 (3) | 5 (7) | 1 (3) | 0.615 | 0 |

| Traumatic brain injury | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.615 | 0 |

| Perinatal spastic hemiparesis | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.644 | 0 |

| Restless legs syndrome | 3 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0.781 | 0 |

| Essential tremor | 2 (1) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.568 | 0 |

| Migraine | 4 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (6) | 0.400 | 0 |

| Neuromuscular disease | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.185 | 0 |

| Epilepsy | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.644 | 0 |

| Poliomyelitis | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.185 | 0 |

| Trigeminal neuralgia | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.644 | 0 |

| Anosmia | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.644 | 0 |

| Other | 10 (7) | 1 (3) | 7 (10) | 2 (6) | 0.493 | 0 |

| Treatment and hospital course | ||||||

| Oxygen requirement | 67 (50) | 31 (100) | 36 (50) | ··· | <0.001 | 1 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 30 (22) | 30 (97) | ··· | ··· | ··· | 0 |

| Steroid treatment | 25 (19) | 13 (42) | 11 (15) | 1 (3) | <0.001 | 1 |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 8 (2–18) | 30 (20–44) | 9 (5–11) | ··· | <0.001 | 0 |

Data are given as median (interquartile range), mean ± standard deviation, and count (%).

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

χ2 or Kruskal‐Wallis tests were used to assess for differences across severity grades (severe, moderate, mild). A p value <0.05 signifies significantly different data distribution across severity groups.

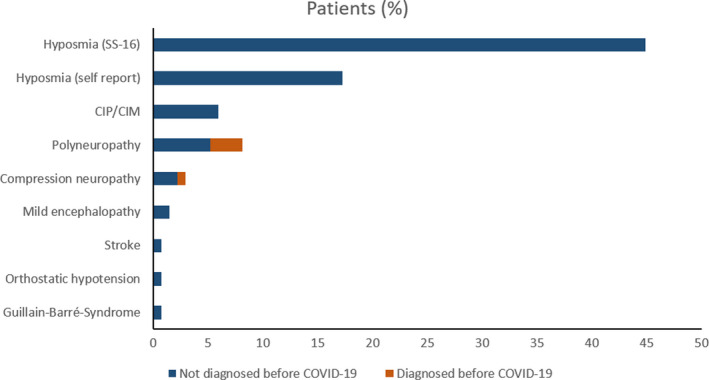

Neurological diseases during the acute disease and 3 months after COVID‐19

Three months after COVID‐19, neurological diseases not diagnosed before COVID‐19 onset were found in 20 patients (15%) and occurred more frequently in ICU patients in comparison to moderate and mild patients (p = 0.001). These included polyneuropathy/myopathy (13%), with one patient presenting with Guillain‐Barré syndrome (1%), mild encephalopathy (2%), parkinsonism (1%), orthostatic hypotension with vasovagal syncope due to autonomic dysregulation (1%), and ischemic stroke (1%; Figure 1). Polyneuropathy/myopathy including CIP/CIM had a higher predominance in the ICU cohort (p < 0.001), whereas there was no difference in other diseases across severity groups. Polyneuropathy/myopathy was associated with ICU‐related complications in 65% of patients, and specific treatment was only applied in one patient with Guillain‐Barré syndrome. None of the patients had convulsive seizures during the acute disease or until follow‐up. One patient with myasthenia gravis had aggravated symptoms during the acute phase and regained her previous state at follow‐up. Three additional patients had aggravated symptoms of preexisting symmetrical distal polyneuropathy at follow‐up. Details are given in Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

Neurological diagnoses before COVID‐19 (red bars) and new‐onset diagnoses (blue bars) 3 months after COVID‐19 in 135 patients. CIP/CIM, critical illness polyneuropathy/critical illness myopathy [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

TABLE 2.

Neurologic diseases at 3 months not diagnosed before COVID‐19

| All, n = 135 | Severe disease requiring ICU admission, n = 31, 23% | Moderate severity, hospitalization, non‐ICU, n = 72, 53% | Mild severity, outpatient, n = 32, 24% | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any neurological disease | 20 (15) | 13 (42) | 5 (7) | 2 (7) | <0.001 |

| Polyneuropathy/myopathy | 17 (13) | 12 (39) | 3 (4) | 2 (6) | <0.001 |

| CIP/CIM | 8 (6) | 8 (26) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| PNP | 7 (5) | 3 (10) | 3 (4) | 1 (3) | 0.427 |

| Compression neuropathy | 3 (2) | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0.116 |

| Guillain‐Barré syndrome | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.185 |

| Parkinsonism | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.185 |

| Cerebellar ataxia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ··· |

| Mild encephalopathy | 2 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.568 |

| Stroke with clinical symptoms | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.644 |

| Orthostatic hypotension | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.185 |

| Seizures | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ··· |

Data are given as count (%).

Abbreviations: CIP/CIM, critical illness polyneuropathy/critical illness myopathy; ICU, intensive care unit; PNP, polyneuropathy.

The χ2 test was used to assess for differences across severity grades (severe, moderate, mild). A p value <0.05 signifies significantly different data distribution across severity groups.

Among patients admitted to the ICU, delirium was reported in 19/31 patients (61%), and 9/31 patients (29%) showed features of encephalopathy of hypoxic (n = 2) or toxic (n = 7) etiology during the acute phase of the disease with improvement over time (1/31, 3% at follow‐up, p = 0.008). Of the ICU cohort, 8 patients (26%) had residual symptoms of critical illness polyneuropathy/myopathy (CIP/CIM) 3 months after diagnosis as compared to 10/31 (30%) during the acute phase (p = 0.500). Patients with CIP/CIM had a longer ICU‐stay compared with those without (28 days; IQR, 17–40 days vs. 15 days; IQR, 8–22 days; p = 0.001, respectively).

Neurological signs and symptoms 3 months after COVID‐19

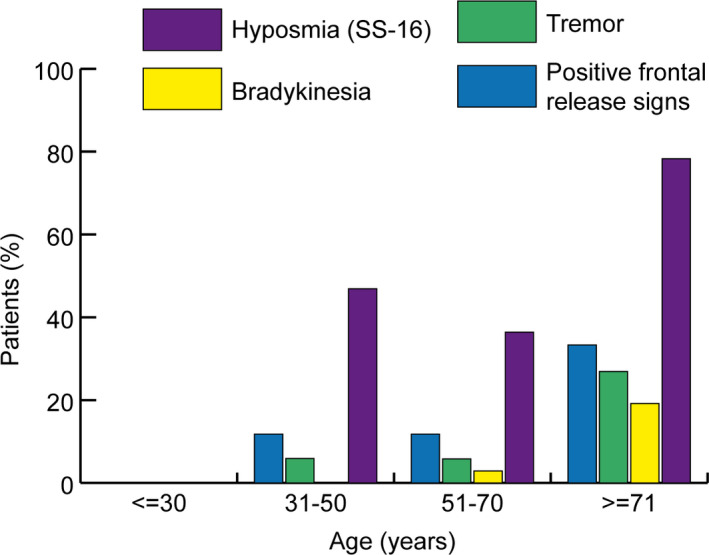

A structured clinical examination revealed relevant neurological signs and symptoms in 82 patients (61%) at follow‐up. Details are provided in Table 3. Hyposmia/anosmia was reported in 17% (23/135), which was less frequent compared to the acute phase of the disease (44%, p < 0.001). Using the SS‐16 test, hyposmia/anosmia was found in 45% of patients (57/127) at the 3‐month follow‐up. Self‐reported headache was a prominent symptom during the acute phase (29%), whereas only 5% of patients reported headache independent of prediagnosed headache syndromes at the 3‐month follow‐up (p < 0.001). Fourteen patients (11%) complained about persistent myalgia 3 months after COVID‐19. Most of them had a severe clinical course requiring ICU admission during acute COVID‐19. Other neurological signs and symptoms at 3 months included abnormal reflex status (n = 31, 23%), positive frontal release signs (n = 20, 15%), tremors (n = 13, 10%), muscle atrophy (n = 9, 7%), bradykinesia (n = 7, 5%), limb paresis (n = 7, 5%), gait abnormality (n = 7, 5%), abnormal muscle tone (n = 6, 4%) or positive pyramidal signs (n = 2, 2%). It is important to mention that tremors were preexisting in 3 patients, muscle atrophy in 2, limb paresis in 4, gait abnormality in 3, spastic muscle tone in 2, and Babinski sign in 1 patient. Figure 2 shows age‐dependent prevalence rates for hyposmia, bradykinesia, tremors, and positive frontal release signs. In general, neurological signs were more common in the elderly; however, hyposmia was also a prominent finding in younger patients.

TABLE 3.

Neurological signs and symptoms 3 months after COVID‐19

| All, n = 135 |

Severe disease requiring ICU admission n=31, 23% |

Moderate severity, hospitalization, non‐ICU n=72, 53% |

Mild severity, outpatient n=32, 24% |

Missing data | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any neurological sign or symptom | 82 (61) | 21 (68) | 42 (58) | 19 (59) | 0 | 0.658 |

| Hyposmia, self‐reported | 21 (16) | 0 (0) | 11 (15) | 10 (31) | 0 | 0.004 |

| Anosmia, self‐reported | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 | |

| Hyposmia/anosmia, SS‐16 | 57 (45) | 13 (46) | 30 (44) | 14 (45) | 0.978 | |

| SS‐16 12‐9 items correct | 48 (38) | 13 (46) | 22 (32) | 13 (42) | 8 | – |

| SS‐16 ≤8 items correct | 9 (7) | 0 (0) | 8 (12) | 1 (3) | – | |

| Hypogeusia, self‐reported | 18 (14) | 0 (0) | 11 (16) | 7 (22) | 2 | 0.018 |

| Change in taste, self‐reported | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 | |

| New cephalea | 7 (5) | 3 (10) | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0.272 |

| Cephalea of known quality and characteristic | 9 (7) | 3 (10) | 6 (8) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0.555 |

| Vertigo/dizziness/lightheadedness, self‐reported | 9 (7) | 2 (7) | 5 (7) | 2 (6) | 0 | 0.990 |

| Neck stiffness | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | – |

| Myalgia/persistent muscle pain | 14 (11) | 6 (20) | 6 (9) | 2 (6) | 3 | 0.154 |

| Decreased consciousness | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | – |

| Dysarthria | 3 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0.781 |

| Aphasia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | – |

| Positive frontal release signs | 20 (15) | 4 (14) | 13 (18) | 3 (9) | 3 | 0.491 |

| Blurring vision, self‐reported | 9 (7) | 1 (3) | 7 (10) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0.314 |

| Oculomotor nerve palsy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | – |

| Facial palsy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | – |

| Dysphagia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | – |

| Bradykinesia | 7 (5) | 4 (13) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.059 |

| Dystonia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | – |

| Chorea | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | – |

| Myoclonus/jerks | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | – |

| Asterixis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | – |

| Dysmetria | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.411 |

| Tremors | 13 (10) | 4 (13) | 9 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.107 |

| Abnormal muscle tone | 6 (4) | 5 (16) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.001 |

| Rigidity | 3 (2) | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | – |

| Spasticity | 2 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | – | – |

| Decreased muscle tone | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | – |

| Muscle atrophy | 9 (7) | 7 (23) | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Decreased/disturbed sensibility | 20 (15) | 8 (26) | 9 (13) | 3 (9) | 0 | 0.134 |

| Numbness/ tingling/burning, self‐reported | 29 (25) | 10 (44) | 11 (17) | 8 (28) | 17 | 0.033 |

| Abnormal reflex status | 31 (23) | 12 (39) | 15 (21) | 4 (13) | 0 | 0.039 |

| Paresis | 7 (5) | 4 (13) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.059 |

| Babinski sign | 2 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0.571 |

| Gait abnormality | 7 (5) | 4 (13) | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 | 0.090 |

Data are given as count (%).

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; SS‐16, 16‐item Sniffin’ Sticks test.

The chi‐square test was used to assess for differences across severity grades (severe, moderate, mild). A P value < 0.05 signifies significantly different data distribution across severity groups.

FIGURE 2.

Age distribution of neurological symptoms including frontal release signs, tremors, bradykinesia, and hyposmia as assessed with the 16‐item Sniffin’ Sticks test (SS‐16) in percentages [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Cognition, mental health, QoL, and functional outcome 3 months after COVID‐19

Cognitive deficits (MoCA) were found in 23% of patients (in severe COVID‐19 patients 29%, moderate 30%, mild 3%). QoL (SF‐36v2) was impaired in 31% (28/90), with 6 patients having restrictions in the PCS, 16 in the MCS, and 6 in both scores. Thirty‐four percent reported sleep disturbances 3 months after COVID‐19. PTSD was diagnosed in 11% of patients (11/98). Depressive and anxiety symptoms were reported by 11% (11/98) and 25% (24/98) of patients, respectively (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Quality of life, cognition, and functional outcome 3 months after COVID‐19

| All, n = 135 | Severe disease requiring ICU admission, n = 31, 23% | Moderate severity, hospitalization, non‐ICU, n = 72, 53% | Mild severity, outpatient, n = 32, 24% | Missing data | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health | ||||||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder, PCL‐5 > 32 | 11 (11) | 4 (17) | 6 (12) | 1 (5) | 37 | 0.427 |

| Depression, HADS‐D | 11 (11) | 3 (13) | 7 (13) | 1 (5) | 37 | 0.569 |

| Depression, HADS‐D >7 | 8 (8) | 1 (4) | 6 (11) | 1 (5) | ··· | ··· |

| Depression, HADS‐D >10 | 3 (3) | 2 (8) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | ··· | ··· |

| Anxiety, HADS‐A | 24 (25) | 5 (21) | 13 (25) | 6 (29) | 37 | 0.834 |

| Anxiety, HADS‐A >7 | 17 (17) | 3 (13) | 9 (17) | 5 (24) | ··· | ··· |

| Anxiety, HADS‐A >10 | 7 (7) | 2 (8) | 4 (8) | 1 (5) | ··· | ··· |

| Quality‐of‐life measures | ||||||

| SF‐36 impaired | 28 (31) | 9 (43) | 16 (31) | 3 (17) | 45 | 0.212 |

| Persistent fatigue | 35 (27) | 15 (50) | 12 (17) | 8 (26) | 4 | 0.003 |

| Sleep disturbances | 45 (34) | 13 (43) | 23 (32) | 9 (28) | 2 | 0.419 |

| Cognition | ||||||

| Forgetfulness, trouble concentrating, difficulty thinking, self‐reported | 30 (25) | 7 (26) | 16 (24) | 7 (24) | 13 | 0.983 |

| MoCA <26 | 29 (23) | 8 (29) | 20 (30) | 1 (3) | 11 | 0.012 |

| MoCA | 28 (26–29) | 28 (25–28) | 28 (25–29) | 29 (28–30) | 11 | <0.001 |

| Functional outcome | ||||||

| GOSE | 8 (7–8) | 7 (7–8) | 8 (7–8) | 8 (7–8) | 0 | 0.015 |

| mRS | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 | 0.005 |

Data are given as median (interquartile range) and count (%). Anxiety and depression (HADS‐A, HADS‐D) were scored as slightly increased when >7 and increased when >10.

Abbreviations: GOSE, Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended; HADS‐A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–Anxiety subscale; HADS‐D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–Depression subscale; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; PCL‐5, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist–5; SF‐36, 36‐item Short Form.

χ2 or Kruskal‐Wallis tests were used to assess for differences across severity grades (severe, moderate, mild). A p value <0.05 signifies significantly different data distribution across severity groups.

Twenty‐seven percent of patients suffered from persistent fatigue 3 months after acute COVID‐19. Fatigue was more frequent in patients with sleep disturbances (adjusted odds ratio [adjOR] = 6.39; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.63–15.53; p < 0.001) and in those with new neurological diagnoses (adjOR = 5.71; 95% CI, 1.76–18.54; p = 0.004).

Overall, functional outcome was good with a median mRS of 1 (0–1) and GOSE of 8 (7–8).

DISCUSSION

In this prospective observational study of 135 COVID‐19 patients, we found neurological diseases unknown before COVID‐19 in every sixth patient at the 3‐month follow‐up with a predominance in ICU patients, including polyneuro/myopathy, mild encephalopathy, parkinsonism, orthostatic hypotension associated with vasovagal syncope, and ischemic stroke. The main neurological symptom was hyposmia/anosmia with a prevalence rate of 45% assessed by the SS‐16 test. Rates of self‐reported hyposmia/anosmia were lower (17%) and significantly improved from disease onset (44%) to the 3‐month follow‐up. Impaired QoL and cognitive deficits were reported in 31% and 23% of patients, respectively. Still, functional outcome was good, with almost all patients living independently at 3 months.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first structured follow‐up report on neurological manifestations of COVID‐19.

Little is known about reversibility or persistence of neurological and neuropsychological manifestations after COVID‐19. The main neurological features at the 3‐month follow‐up were hyposmia/anosmia as well as (critical illness) polyneuro/myopathy in our cohort. The observed prevalence rate of self‐reported hyposmia/anosmia is comparable to previous reports during the acute disease and at a 2‐month follow‐up [13]. Despite significant improvement over time in our cohort, we observed a high discrepancy between objective testing (45%) and self‐reported hyposmia/anosmia (17%). This observation has been previously reported [25, 26. Of interest is that none of the severe COVID‐19 patients admitted to the ICU reported hyposmia/anosmia at follow‐up, although objective assessment was abnormal in every second patient. To date, it is still unclear whether olfactory dysfunction following COVID‐19 is a consequence of angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) receptor downregulation of the olfactory epithelium or results due to structural abnormalities of the olfactory bulb, primary olfactory cortex (gyrus piriformis), or secondary projection areas including the limbic lobe, thalamus, and anterior cingulum [27]. Advanced neuroimaging studies suggested a decreased volume of the gray matter in patients with persistent hyposmia 3 months after disease compared to COVID‐19 patients without anosmia [14]. Another study found an association between transient edema of the olfactory bulb and smelling disorders [28]. In addition, fluid‐attenuated recovery images on cerebral MRI revealed signal hyperintensities in the olfactory bulb and frontobasal cortical areas in a patient suffering from hyposmia [29]. After recovery, signal alterations of cortical grey matter regions completely disappeared, and the olfactory bulbs appeared thinner. Although careful evaluation for publication bias is warranted, these findings may support a direct virus‐associated pathology of neuronal tissue in humans. Besides the retrograde neuronal spread, the sensory organs of smell may also be affected by excessive or uncontrolled production of immune cells and cytokines, a breakdown of the blood–brain barrier, or microvascular damage [27].

Encephalopathy was reported in one third of ICU patients during acute disease stages, with only one of those patients having persistent features 3 months after disease onset. Frontal release signs were positive in 15% of our patients at follow‐up, which are unspecific but commonly found in patients with encephalopathy. Encephalopathy and frontal signs were highly prevalent in another cohort of 58 severe COVID‐19 patients admitted to the hospital because of ARDS [2]. In all patients of this study who underwent cerebral MRI because of unexplained encephalopathic features, bilateral frontotemporal hypoperfusion was noted [2]. Limited evidence suggests a direct virus‐associated etiology of encephalopathy in COVID‐19 patients, and therefore, it is more likely that encephalopathy occurs secondary due to inflammation or other systemic effects including organ failure [30, 31.

Cognitive deficits as assessed with the MoCA were frequent 3 months after COVID‐19 diagnosis, predominantly affecting hospitalized patients. Every second patient diagnosed with encephalopathy during their ICU stay had cognitive deficits as compared to 23% in the overall cohort. We cannot exclude that non‐overt cognitive deficits were undiagnosed before COVID‐19 in these patients. Interestingly, self‐reported cognitive deficits (e.g., forgetfulness, trouble in concentrating, difficulty in thinking) were equally reported independent of severity groups (24%–26%), even in patients with mild disease (24%). Other groups recently reported that the estimated prevalence for dementia after COVID‐19 is higher during a 6‐month follow‐up period compared with patients after influenza or other respiratory tract infections [32]. Further longitudinal studies with detailed neuropsychological testing are necessary to evaluate whether cognitive deficits improve over time.

Although several studies indicate the involvement of the CNS and PNS after COVID‐19, it remains unclear which patients are at highest risk to develop relevant neurological manifestations. Our data indicate that severely affected patients have higher rates of persistent neurological features 3 months after disease onset as compared with patients with milder disease courses.

The most prevailing finding involving the PNS were signs of CIP/CIM seen in every third patient admitted to the ICU during the acute disease, which is comparable to patients admitted with ARDS [33]. Although symptoms alleviated in our cohort, 8 patients still exhibited residual signs of CIP/CIM after 3 months. Sepsis and multiorgan failure as seen in severely affected COVID‐19 patients are well‐established risk factors for CIP/CIM [12]. In addition, SARS‐CoV‐2– associated endothelial cell activation together with direct viral invasion, hypercoagulopathy, inflammation, and microcirculatory injury may aggravate peripheral nerve injury in COVID‐19 patients [34]. The observed muscle atrophy in our patients is likely attributable to immobilization, CIP/CIM, and compression neuropathy predominantly found in ICU patients.

Persistent myalgia 3 months after COVID‐19 was reported by 11% of our patients, with a predominance in hospitalized patients, similar to previous reports [13]. Postulated underlying mechanisms include a virus‐triggered inflammatory response or direct muscle toxicity [35]. The virus may infiltrate the muscle via the ACE‐2 receptor, which is expressed on skeletal muscles [36]. In turn, immune‐mediated mechanisms include muscle damage through T‐cell expansion or proinflammatory cytokine and macrophage‐mediated muscle fiber injury [37]. Immune‐mediated toxicity of the virus has been described in the setting of para‐ and postinfectious immune‐mediated diseases such as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis [38] or myelitis [39]. Similarly, the peripheral nervous system is affected by immune‐mediated disease with Guillain‐Barré syndrome or variants reported in patients after COVID‐19 [40, 41. We report 1 COVID‐19 patient who developed Guillain‐Barré syndrome and showed good recovery 3 months after disease onset [42].

Impairment of QoL, anxiety and depressed mood, sleep disorders, and PTSD were found in a considerable number of patients. These manifestations have a substantial socioeconomic burden on mental health. Close surveillance to ensure early detection of potentially treatable conditions and the provision of targeted treatment strategies including psychological support seems important in recovered patients. It is worth mentioning that some neuropsychiatric findings may be not associated with the disease itself but with the overall social consequences related to the pandemic. Accordingly, also non–COVID‐19 patients developed depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms during the pandemic [43]. The number of people affected by these symptoms was found to have increased since onset of the pandemic, predominantly affecting young female patients with low incomes [44].

Fatigue was reported in 50% of ICU patients and in every fourth patient with mild disease in our cohort. This is in line with previous studies reporting fatigue in 53% of hospitalized COVID‐19 patients 2 months after symptom onset [13] and in another study reporting fatigue or muscle weakness in 63% (1038/1655) of survivors 6 months after COVID‐19 [45]. We found an association between disturbed sleep and the diagnosis of a new‐onset neurological disease not diagnosed before COVID 19 and fatigue. Based on our data and previous publications, fatigue does not seem to be limited to severe cases.

There are limitations to this study that should be discussed. Firstly, our study design does not allow us to conclude causality between COVID‐19 and the reported neurological symptoms and diseases, and there is the possibility of a chance association. To minimize this bias, we carefully evaluated preexisting neurological disorders and found that every third patient had neurologic consultancy before COVID‐19 onset. Similarly, we did not assess baseline MoCA to quantify preexisting cognitive impairment. We only recorded relevant clinical findings that were diagnosed by a neurological consultancy during the acute disease or by physicians prior to disease onset. This is also important for parkinsonism, which may have been diagnosed by a proper neurological examination before COVID‐19. Secondly, neurological assessment 3 months after disease onset may not sufficiently represent long‐term consequences of this disease. Therefore, several initiatives call for a minimum 12‐month follow‐up [46]. Thirdly, underrepresentation of COVID‐19 patients with mild disease may have led to a substantial bias in reported prevalence rates. Still, the strength of our study lies in the inclusion of all severity grades ranging from mild disease to severe manifestations requiring ICU admission. Our data should be interpreted in the context of a healthcare system that never collapsed during the pandemic.

CONCLUSION

In summary, despite recovery from acute infection, neurological abnormalities were common at the 3‐month follow‐up. Although neurological diseases were diagnosed in every sixth patient, smelling disorders were more prevalent (45%), even in COVID‐19 patients recovering from mild disease. Every third patient reported poor QoL at the 3‐month follow‐up. Importantly, 3‐month functional outcome was good, and nearly all patients regained functional independence. Early identification of patients at high risk for persistent neurologic features is important to evaluate these patients for further neuro‐rehabilitative support and to develop strategies for secondary prevention. Further studies investigating socioeconomic and neurological long‐term consequences of COVID‐19 beyond 3 months are needed.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

K.S. reports grants from the FWF Austrian Science Fund, Michael J. Fox Foundation, and the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society; and personal fees from Teva, UCB, Lundbeck, AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals AG, Abbvie, Roche, and Grünenthal; all outside the submitted work. P.M. reports grants from TWF (Tyrolean Science Fund) and Medtronic, and personal fees from Boston Scientific, all outside the submitted work. The other authors have nothing to disclose. All other authors declare no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.H., V.R., T.S., I.T., J.L.R., and G.W. designed and oversaw the study. V.R., R.H., R.B., A.J.S., M.K., A.L., P.M., B.H., V.L., S.S., A.P., T.S., I.T., J.L.‐R., C.S., R.B.‐W., A.D., K.S., and B.P. performed neurological assessment and collected the data. L.Z. performed analysis of neuropsychological data. V.R., R.H., S.K., and G.W. interpreted the data. V.R. and R.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to and critically reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all of the physicians and nurses involved in the acute‐care management of COVID‐19 patients in Innsbruck, Zams, and Muenster.

REFERENCES

- 1. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2268‐2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Romero‐Sánchez CM, Díaz‐Maroto I, Fernández‐Díaz E, et al. Neurologic manifestations in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19: the Albacovid Registry. Neurology. 2020;95(8):e1060‐e1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ellul M, Benjamin L, Singh B, et al. Neurological associations of COVID‐19. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(9):767–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zubair AS, McAlpine LS, Gardin T, Farhadian S, Kuruvilla DE, Spudich S. Neuropathogenesis and neurologic manifestations of the coronaviruses in the age of coronavirus disease 2019: a review. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(8):1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Frontera JA, Sabadia S, Lalchan R, et al. A prospective study of neurologic disorders in hospitalized COVID‐19 patients in New York city. Neurology. 2020;96(4):e575–e586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moro E, Priori A, Beghi E, et al. The international European Academy of Neurology survey on neurological symptoms in patients with COVID‐19 infection. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1727‐1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Romoli M, Jelcic I, Bernard‐Valnet R, et al. A systematic review of neurological manifestations of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: the devil is hidden in the details. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27(9):1712‐1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gu J, Gong E, Zhang BO, et al. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med. 2005;202:415‐424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Solomon IH, Normandin E, Bhattacharyya S, et al. Neuropathological features of COVID‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(10):989‐992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Latronico N, Bolton CF. Critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy: a major cause of muscle weakness and paralysis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:931‐941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carfi A, Bernabei R, Landi F; Gemelli Against C‐P‐ACSG . Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID‐19. JAMA. 2020;324:603‐605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lu Y, Li X, Geng D, et al. Cerebral micro‐structural changes in COVID‐19 patients ‐ an MRI‐based 3‐month follow‐up study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25:100484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Varatharaj A, Thomas N, Ellul MA, et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID‐19 in 153 patients: a UK‐wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):875–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta‐analysis with comparison to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:611‐627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sonnweber T, Sahanic S, Pizzini A, et al. Cardiopulmonary recovery after COVID‐19 ‐ an observational prospective multi‐center trial. Eur Respir J. 2020;57:2003481. 10.1183/13993003.03481-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Klein SJ, Bellmann R, Dejaco H, et al. Structured ICU resource management in a pandemic is associated with favorable outcome in critically ill COVID19 patients. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2020;132:653‐663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hummel T, Kobal G, Gudziol H, Mackay‐Sim A. Normative data for the "sniffin’ sticks" including tests of odor identification, odor discrimination, and olfactory thresholds: an upgrade based on a group of more than 3,000 subjects. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:237‐243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The montreal cognitive assessment, moca: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695‐699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The mos 36‐item short‐form health survey (sf‐36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473‐483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blanchard EB, Jones‐Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:669‐673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hermann C, Buss U, Snaith RP. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ‐ German Version (Hads‐D). Bern: Huber; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hansson M, Chotai J, Nordstom A, Bodlund O. Comparison of two self‐rating scales to detect depression: Hads and phq‐9. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59:e283‐288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moein ST, Hashemian SM, Mansourafshar B, Khorram‐Tousi A, Tabarsi P, Doty RL. Smell dysfunction: a biomarker for COVID‐19. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020;10:944‐950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hornuss D, Lange B, Schroter N, Rieg S, Kern WV, Wagner D. Anosmia in COVID‐19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1426‐1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kanjanaumporn J, Aeumjaturapat S, Snidvongs K, Seresirikachorn K, Chusakul S. Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatment options. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2020;38:69‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eliezer M, Hamel AL, Houdart E, et al. Loss of smell in COVID‐19 patients: MRI data reveals a transient edema of the olfactory clefts. Neurology. 2020;95(23):e3145‐e3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Politi LS, Salsano E, Grimaldi M. Magnetic resonance imaging alteration of the brain in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and anosmia. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(8):1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al. Covid‐19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033‐1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Perrin P, Collongues N, Baloglu S, et al. Cytokine release syndrome‐associated encephalopathy in patients with COVID‐19. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:248‐258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. Six‐month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236,379 survivors of COVID‐19. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33. Hough CL, Steinberg KP, Taylor Thompson B, Rubenfeld GD, Hudson LD. Intensive care unit‐acquired neuromyopathy and corticosteroids in survivors of persistent ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:63‐68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aghagoli G, Gallo Marin B, Katchur NJ, Chaves‐Sell F, Asaad WF, Murphy SA. Neurological involvement in COVID‐19 and potential mechanisms: a review. Neurocrit Care. 2020. 10.1007/s12028-020-01049-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pitscheider L, Karolyi M, Burkert FR, et al. Muscle involvement in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Eur J Neurol. 2020. 10.1111/ene.14564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cabello‐Verrugio C, Morales MG, Rivera JC, Cabrera D, Simon F. Renin‐angiotensin system: an old player with novel functions in skeletal muscle. Med Res Rev. 2015;35:437‐463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dalakas MC. Guillain‐barre syndrome: the first documented COVID‐19‐triggered autoimmune neurologic disease: more to come with myositis in the offing. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7(5):e781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Parsons T, Banks S, Bae C, Gelber J, Alahmadi H, Tichauer M. Covid‐19‐associated acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). J Neurol. 2020;267(10):2799‐2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Munz M, Wessendorf S, Koretsis G, et al. Acute transverse myelitis after COVID‐19 pneumonia. J Neurol. 2020;267:2196‐2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Uncini A, Vallat JM, Jacobs BC. Guillain‐barre syndrome in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: an instant systematic review of the first six months of pandemic. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91:1105‐1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. De Sanctis P, Doneddu PE, Vigano L, Selmi C, Nobile‐Orazio E. Guillain‐barre syndrome associated with Sars‐CoV‐2 infection. A systematic review. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:2361‐2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Helbok R, Beer R, Loscher W, et al. Guillain‐barre syndrome in a patient with antibodies against SARS‐CoV‐2. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27(9):1754–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. González‐Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos MÁ, et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID‐19) in Spain. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:172‐176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pieh C, Budimir S, Probst T. The effect of age, gender, income, work, and physical activity on mental health during coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) lockdown in Austria. J Psychosom Res. 2020;136.110186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6‐month consequences of COVID‐19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220‐232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Helbok R, Chou SH, Beghi E, et al. Neurocovid: it's time to join forces globally. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:805‐806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1