Abstract

Background/Objectives

Differences in older adults' worry, attitudes, and mental health between high‐income countries with diverging pandemic responses are largely unknown. We compared COVID‐19 worry, attitudes towards governmental responses, and self‐reported mental health symptoms among adults aged ≥55 in the United States and Canada early in the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Design

Online cross‐sectional survey administered between April 2nd and May 31st in the United States and between May 1st and June 30th, 2020 in Canada.

Setting

Nationally in the United States and Canada.

Participants

Convenience sample of older adults aged ≥55.

Measurements

Likert‐type scales measured COVID‐19 worry and attitudes towards government support. Three standardized scales assessed mental health symptoms: the eight‐item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, the five‐item Beck Anxiety Inventory, and the three‐item UCLA loneliness scale.

Results

There were 4453 U.S. respondents (71.7% women; mean age 67.5) and 1549 Canadian (67.6% women; mean age 69.3). More U.S. respondents (71%) were moderately or extremely worried about the pandemic, compared to 52% in Canada. Just 20% of U.S. respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the federal government cared about older adults in their COVID‐19 pandemic response, compared to nearly two‐thirds of Canadians (63%). U.S. respondents were more likely to report elevated depressive and anxiety symptoms compared to Canadians; 34.2% (32.8–35.6) versus 25.6% (23.3–27.8) for depressive and 30.8% (29.5–32.2) versus 23.7% (21.6–25.9) for anxiety symptoms. The proportion of United States and Canadian respondents who reported loneliness was similar. A greater proportion of women compared to men reported symptoms of depression and anxiety across all age groups in both countries.

Conclusion

U.S. older adults felt less supported by their federal government and had elevated depressive and anxiety symptoms compared to older adults in Canada during early months of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Public health messaging from governments should be clear, consistent, and incorporate support for mental health.

Keywords: COVID‐19, mental health, older adults, government, pandemic response

Key Points

This is one of the first studies comparing the concerns and mental health of older adults between similar high‐income countries with differing COVID‐19 epidemic curves and governmental responses.

US older adults felt less supported by their federal government and may experience elevated worry, depressive and anxiety symptoms compared to older adults in Canada.

As the COVID‐19 pandemic unfolds, there should be clear and consistent public health communication and equitable interventions to manage the additional mental health needs of older adults.

Why Does this Paper Matter?

This study provides crucial information about the mental health distress reported by older adults in US and Canada during the early months of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Our results highlight the importance of government messaging that is clear, consistent and incorporates support for older adults.

INTRODUCTION

Older adults are a high‐risk group for severe morbidity and mortality from Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), 1 but the emotional harms associated with the pandemic are largely unknown for this population. 2 Many countries have implemented physical distancing and shelter‐in‐place orders, often with specific emphasis on older adults. 3 While evidence from the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) pandemic indicated negative mental health effects of quarantine and isolation, there remains a paucity of data on the mental health of older adults during infectious disease pandemics. 4 , 5 , 6 The World Health Organization has emphasized that older adults may become more anxious during the COVID‐19 pandemic, due to their greater need for physical isolation. 7 Indeed, older adults in the United States reported worsened loneliness during shelter‐in‐place orders. 8 These findings highlight the urgency to study the mental health impact of COVID‐19 among older adults so that adverse outcomes can be anticipated and minimized by clinicians, health systems and communities.

While nationally representative pre‐pandemic data has identified negligible differences in prevalence of mental health diagnoses and depressive symptomology in the United States and Canada, 9 , 10 the mental health experiences and COVID‐19 concerns of older adults in the US and Canada are unknown. These two neighboring countries had vastly different epidemic curves and governmental responses, public health messaging, and social norms about transmission control in the early months of the pandemic. 11 , 12 Worry about support from or lack of confidence in government during significant societal events such as the COVID‐19 pandemic may negatively impact the mental health of older adults. 13 Assessing the relationships of the societal climate and governmental responses with mental health status of older adults in these two countries could have important public policy implications, especially as COVID‐19 cases remain relatively low in Canada compared to surges in the United States at the time of writing. 14 , 15

We aimed to compare levels of COVID‐19‐related worry, attitudes towards governmental response, and self‐reported mental health symptoms during the early months of the COVID‐19 pandemic among older men and women in the United States and Canada. We hypothesized that US respondents, particularly women, would experience worse mental health, greater COVID‐19 worry, and feel less supported by their government compared to their Canadian counterparts.

METHODS

Study design and participants

We conducted a cross‐sectional analysis of baseline data from two parallel longitudinal studies administered in the United States and Canada during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The survey was developed at the University of Michigan16 and modified for the Canadian context. Information collected included sociodemographic data, COVID‐19 related perspectives and impacts on daily life, attitudes towards government pandemic responses and mental health symptoms. Where possible, we followed the guidelines described in the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E‐Surveys (CHERRIES). 17

The U.S. survey was administered April 2nd to May 31st, and the Canadian survey May 1st to June 30th, 2020. Across most of the U.S. stay at home orders were in effect by the end of March or early April. Daily cases peaked in April and were in decline in May; and most states had begun lifting restrictions in May. 14 In Canada, physical distancing measures were in place beginning in March and most provinces started easing restrictions as cases declined after a peak in early May. We recruited eligible participants aged ≥55 in both countries using convenience and snowball sampling through social media platforms and targeted recruitment to societies and organizations with older adult membership. Although age 65 is typically used to define older persons, we used a cut‐off of 55, recognizing that aging is both a biological and social construct and some individuals, for example, those who endure poverty, may experience aging earlier than others. 18 We administered the surveys using Qualtrics 19 in English and Spanish in the US, and English and French in Canada. The questionnaires were professionally translated and pretested in all three languages for usability, technical functionality, clarity, and timing. All participants provided online informed consent. No monetary incentives were provided. This study received research ethics board approval through the Women's College Hospital Research Ethics Board (REB # 2020‐0045‐E) and the University of Michigan Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB # HUM00179632). Further details regarding survey procedures and administration are outlined in Data S1.

Outcomes

We used 5‐point Likert‐type response scales to assess COVID‐19 worry, perceptions of assistance from community, attitudes towards level of federal and state (United States) or provincial (Canada) government care towards older adults and societal respect for older adults during the pandemic. We used validated cut‐offs on three standardized mental health symptom scales: the eight‐item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D), the five‐item Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and the 3‐item UCLA Loneliness Scale. Additional details about the selection and validation of these mental health scales can be found in Data S1.

Analysis

We conducted a parallel description of data from each country, as the Canadian research ethics board restricted international data merges. Characteristics of each country sample were described using univariate statistics. Likert‐type scale responses were converted to percentages for each agreement category, and agree and strongly agree categories were combined and compared across countries. We estimated the proportion of respondents with elevated depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and loneliness in each country, overall and by sex within each age group, with 95% confidence intervals calculated by binomial distribution. Mental health symptom differences between countries were considered meaningful if confidence intervals did not overlap. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC) for the Canadian sample and Stata 16.0 (College Station, TX) for the U.S. sample.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Survey completion rates were 87% in the Canadian sample (N = 1549) and 84% in the U.S. sample (N = 4453; see Figure S1 in the Supplemental File). Most respondents were women (67.6% Canada, 71.7% U.S.), and between 65 and 74 years of age (46.9% Canada, 43.8% U.S.) (Table 1). Respondents were predominantly white (95.8% Canada, 94.3% U.S.), had a bachelor or graduate degree (56.7% Canada, 80.4% U.S.), and were in excellent or very good self‐reported health (60.3% Canada, 59.5% U.S.). Similar proportions of respondents were living alone in both countries (27.0% Canada, 26.5% U.S.).

TABLE 1.

Socio‐demographic characteristics of United States and Canadian respondents

| Characteristics | Canada, N (%) | United States, N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 1045 (67.6) 1 | 3194 (71.7) |

| Language of survey | ||

| English | 1423 (91.9) | 4401 (98.8) |

| Spanish | — | 52 (1.2) |

| French | 126 (8.1) | — |

| Average age years (SD) | 69.3 (7.8) | 67.5 (7.5) |

| Age categories in years | ||

| 55–64 years | 459 (29.6) | 1765 (39.6) |

| 65–74 years | 726 (46.9) | 1951 (43.8) |

| 75–84 years | 304 (19.6) | 652 (14.6) |

| 85+ years | 60 (3.9) | 85 (1.9) |

| Race a | ||

| White | 1484 (95.8) | 4197 (94.3) |

| Black or African Canadian/African American | 7 (0.5) | 124 (2.8) |

| Indigenous peoples | 21 (1.4) | 55 (1.2) |

| South Asian | 12 (0.8) | 15 (0.3) |

| East Asian | 12 (0.8) | 47 (1.1) |

| Middle‐Eastern | 3 (0.2) | 22 (0.5) |

| Other | 51 (3.3) | 77 (1.7) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 3 (0.2) | 128 (2.9) |

| Education | ||

| High school/less than high school | 246 (15.9) | 157 (3.5) |

| Some college or university, college diploma, trade or two‐year associate's degree | 425 (27.5) | 715 (16.1) |

| Bachelor degree | 394 (25.5) | 1435 (32.2) |

| Graduate degree | 482 (31.2) | 2146 (48.2) |

| Pre‐COVID employment status | ||

| Employed | 315 (20.4) | 1968 (44.2) |

| Retired | 1208 (78.2) | 2270 (51.0) |

| Unemployed | 21 (1.4) | 213 (4.8) |

| Living alone | 415 (27.0) | 1170 (26.5) |

| Current relationship status | ||

| Single/widowed | 478 (31.1) | 1471 (33.1) |

| Married or in a relationship | 1058 (68.9) |

2975 (66.9) |

| Self‐reported health | ||

| Excellent | 294 (19.2) | 881 (19.8) |

| Very good | 631 (41.1) | 1766 (39.7) |

| Good | 441 (28.8) | 1280 (28.8) |

| Fair | 149 (9.7) | 440 (9.9) |

| Poor | 19 (1.2) | 81 (1.8) |

| Mobility aid use b | 158 (10.2) | 578 (8.5) |

| Multi‐morbidity (>2 reported chronic conditions) | 594 (39.2) | 3029 (44) |

Note: total sample sizes: Canada = 1549 and United States = 4453.

Includes cane, walker, wheelchair, motorized scooter.

% adds to >100 to allow for multiple selections per person, people who reported multiple races were included in the “Other” category.

Perspectives related to COVID‐19

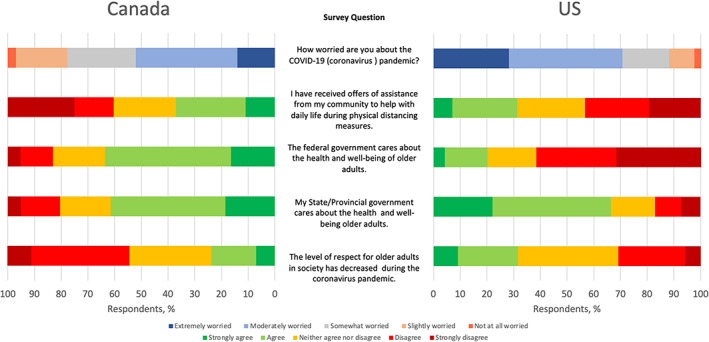

U.S. respondents were more likely than Canadian respondents to report being extremely or moderately worried about COVID‐19 (71% vs 52%, respectively; Figure 1). Just one in five U.S. respondents (20%) agreed or strongly agreed that their federal government cared about the health and well‐being of older adults in their COVID‐19 response, compared to nearly two‐thirds of Canadian respondents (63%; Figure 1). In contrast, agreement that state or provincial governments cared about older adults' health and well‐being during COVID‐19 was similar in both countries (66% United States, 59% Canada, Figure 1). Responses about respect for older adults and offers of community assistance were similar between countries (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

COVID‐19 worries, attitudes and perspectives on government support during the pandemic

Mental health symptoms during the COVID‐19 pandemic

U.S. respondents were more likely to report elevated depressive and anxiety symptoms compared to Canadian respondents, with 34.2% (95% CI: 32.8–35.6%) versus 25.6 (95% CI: 23.3–27.8%) for depressive and 23.7% (95% CI: 21.6–25.9%) vs 30.8% (95% CI: 29.5–32.2%) for anxiety symptoms (Table 2). Across both countries, women were more likely than men to report elevated depressive symptoms: 17.0% (95% CI: 13.5–20.5%) for men versus 29.4% (95% CI: 26.5–32.4%) for women in Canada and 25.9% (95% CI: 23.5–28.4%) for men versus 37.4% (95% CI: 35.8–39.2%) for women in the United States. Women were also more likely to report elevated anxiety symptoms 19.0% (95% CI: 15.5–22.5%) for men versus 26.0% (95% CI: 23.3–28.7%) for women in Canada and 23.9 (95% CI: 21.5–26.4%) for men and 33.6% (95% CI: 31.9–5.2%) for women in the U.S. The proportion of respondents reporting loneliness was similar across both countries, with women reporting higher loneliness than men in both countries (Table 2). Across all four age categories, both U.S. and Canadian women were more likely to report depressive, anxiety, and loneliness symptoms compared to men of the same age (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Differences in self‐reported symptoms of depression, anxiety and loneliness between United States and Canadian survey respondents

| Canada (%, 95% CI) | United States (%, 95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Depression a | ||||

| Overall | 25.6 (23.3–27.8) | 34.2 (32.8–35.6) | ||

| 17.0 (13.5–20.5) | 29.4 (26.5–32.4) | 25.9 (23.5, 28.4) | 37.4 (35.8, 39.2) | |

| Age category | ||||

| 55–64 years | 20.2 (12.7–27.7) | 33.0 (27.9–38.2) | 35.7 (31.1, 40.6) | 45.2 (42.6, 47.9) |

| 65–74 years | 16.7 (11.5–21.9) | 26.7 (22.7–30.7) | 24.0 (20.5, 27.7) | 33.6 (31.1, 36.2) |

| 75–84 years | 13.6 (7.2–20.1) | 29.8 (22.5–37.1) | 14.6 (10.4, 19.7) | 25.8 (21.6, 30.4) |

| 85+ years | 20.8 (4.6–37.1) | 31.3 (8.5–54.0) | 17.5 (7.3, 32.8) | 27.3 (15.0, 42.8) |

| Anxiety b | ||||

| Overall | 23.7 (21.6–25.9) | 30.8 (29.5–32.2) | ||

| 19.0 (15.5–22.5) | 26.0 (23.3–28.7) | 23.9 (21.5, 26.4) | 33.6 (31.9, 5.2) | |

| Age category | ||||

| 55–64 years | 22.2 (14.7–29.8) | 27.9 (23.1–32.8) | 27.4 (23.2, 32.1) | 40.1 (37.5, 42.8) |

| 65–74 years | 17.7 (12.5–22.9) | 26.0 (22.2–29.9) | 24.6 (21.1, 28.4) | 31.2 (28.8, 33.7) |

| 75–84 years | 19.2 (12.5–26.0) | 24.1 (17.6–30.6) | 17.2 (12.7, 22.6) | 21.6 (17.7, 26.0) |

| 85+ years | 14.3 (1.3–27.3) | 14.3 (1.3–27.3) | 17.5 (7.3, 32.8) | 14.0 (5.3, 27.9) |

| Loneliness c | ||||

| Overall | 28.4 (26.2–30.7) | 29.2 (27.9, 30.6) | ||

| 20.9 (17.3–24.5) | 31.9 (29.0–34.7) | 23.1 (20.8, 25.5) | 31.6 (30.0, 33.3) | |

| Age category | ||||

| 55–64 years | 31.6 (23.2–40.1) | 31.1 (26.2–36.1) | 31.3 (26.9, 36.0) | 45.2 (42.6, 47.9) |

| 65–74 years | 18.8 (13.5–24.0) | 32.5 (28.4–36.6) | 20.1 (16.8, 23.7) | 30.6 (28.8, 33.7) |

| 75–84 years | 16.5 (10.2–22.9) | 32.1 (25.1–39.2) | 16.3 (11.8, 21.7) | 24.9 (20.7, 29.6) |

| 85+ years | 13.8 (1.2–26.3) | 28.6 (11.8–45.3) | 18.9 (8.0, 35.2) | 26.2 (13.9, 42.0) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Calculated using CESD score 3+, CIs calculated using binomial distribution, missing 144 in Canada, 17 in United States.

Calculated using BAI score 10+, CIs calculated using binomial distribution, missing 35 in Canada, 68 in United States.

Calculated using UCLA loneliness score 6+, CIs calculated using binomial distribution, missing 18 in Canada, 97 in United States.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare differences in concerns, worries, and mental health symptoms between older Canadians and Americans during the COVID‐19 pandemic. We found that just 20% of U.S. respondents felt their federal government cared about older adults in their COVID‐19 response, consistent with a recent study showing that 33% of U.S. respondents trusted the federal government to manage the COVID‐19 pandemic. 20 In contrast, we found that 63% of Canadian respondents felt their federal government cared about older adults in their COVID‐19 response. In Canada, there was an early coordinated response across federal and provincial jurisdictions with respect to purchasing supplies, messaging about mask‐wearing, testing, and economic relief. 12 In contrast, there has been political polarization in the United States with conflict between state governors and presidential leadership over nearly all aspects of the COVID‐19 response. 21 Acute health care systems in Canada have been able to manage patient volumes without being overwhelmed. 22 In contrast, health care system demand has exceeded capacity in many U.S. jurisdictions, 23 and the death rate has been more than double that of Canada. 11 Canadian universal coverage of healthcare, home care and medications may have also played a role in alleviating concerns among older Canadians. As older adults are at greatest risk of COVID‐19 morbidity and mortality, these differences may have contributed to increased mental health distress in the United States compared to Canada.

Consistent with our hypothesis, the prevalence of elevated depressive or anxiety symptoms was higher in older Americans compared to older Canadians during the early months of the pandemic. Our results are consistent with a recent survey showing that American adults report greater mental health challenges related to COVID‐19 compared to eight other high‐income nations. 20 Data from nationally representative cohort studies in 2019, before the pandemic, indicates that prevalence of elevated depressive symptoms in 2019 was similar between U.S. adults aged ≥50 (16.4%) 10 and Canadian adults aged ≥50 (15.3%). 9

This study adds valuable information regarding the mental health impacts of COVID‐19 on older adults. Cross‐sectional surveys from the United States, the United Kingdom, and China have evaluated mental health distress, but have under‐represented older adults and have not reported findings by sex within older age groups. 24 , 25 , 26 We found that a greater proportion of older women than men reported mental health symptoms across all age groups in both countries. Older women may need additional support throughout the pandemic, which is not surprising given they are more likely than men to live alone and rely on a caregiver for support. 27 Respondents aged ≥65 had better mental health than those 55–64, a noteworthy finding that has been reported in other COVID‐19 surveys, and may suggest higher resilience of those in older age groups to the mental health effects of COVID‐19. 28 Though older adults may possess greater resilience, there is still a need for better access to resources to support mental health and address gender‐based inequalities in mental well‐being during the pandemic. 29

A limitation is that our non‐probability‐based sampling strategy prevents us from generating population‐representative prevalence estimates. However, we were able to rapidly enroll two large cohorts of older adults during a public health crisis, using a snowball sampling method that has been shown to improve representation of groups who are harder to reach through Internet‐based sampling alone. 16 Though baseline characteristics were similar between groups, comparisons should be made cautiously given the potential for underlying differences in the two convenience samples. The heterogeneity of COVID‐19 case rates between the two countries and the survey timing (April–May in the United States and May–June in Canada) may have impacted reporting of pandemic‐related concerns. If the missing depression data in the Canadian sample (n = 144) were non‐random by depression status, we may have underestimated or overestimated depressive symptoms. The use of self‐reported outcomes and mental health screening tools that assess symptomatology is a limitation, and outcomes should not be interpreted as diagnosed psychiatric disorders, although they may capture undiagnosed depression and anxiety. The perspectives of vulnerable groups who may be at greater risk of adverse mental health outcomes (e.g., low income, no home internet access) are likely under‐represented.

This study provides important exploratory findings regarding the mental health experiences of older adults in the U.S. and Canada during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Older adults in the United States may face greater mental health challenges and feel less supported by government compared to older adults in Canada. Public health messaging in both countries should be clear, consistent, and incorporate support for mental health. As the full extent and duration of the COVID‐19 pandemic remains unknown, there should be targeted and equitable public health and community interventions to manage the additional mental health needs of older adults.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors listed have contributed significantly to study conception and design and/or data acquisition and/or analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors were involved in the manuscript's preparation, revision and final approval of version to be published.

SPONSOR'S ROLE

The study did not receive any external funding.

Supporting information

Data S1 Text S1: Additional methodology details.

Figure S1: Recruitment flow chart.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Rochon holds the Retired Teachers of Ontario/Les enseignantes et enseignants retraités de l'Ontario (RTO/ERO) Chair in Geriatric Medicine at the University of Toronto.

Reppas‐Rindlisbacher C, Finlay JM, Mahar AL, et al. Worries, attitudes, and mental health of older adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Canadian and U.S. perspectives. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:1147–1154. 10.1111/jgs.17105

REFERENCES

- 1. Yanez ND, Weiss NS, Romand J‐A, et al. COVID‐19 mortality risk for older men and women. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Armitage R, Nellums LB. COVID‐19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daoust JF. Elderly people and responses to COVID‐19 in 27 countries. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0235590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(7):1206‐1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yip PS, Cheung YT, Chau PH, Law YW. The impact of epidemic outbreak: the case of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and suicide among older adults in Hong Kong. Crisis. 2010;31(2):86‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barbisch D, Koenig KL, Shih FY. Is there a case for quarantine? Perspectives from SARS to Ebola. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2015;9(5):547‐553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. WHO . Mental health and psychosocial considerations during COVID‐19 outbreak. 2020; http://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf?sfvrsn=6d3578af_2. Accessed August 29, 2020.

- 8. Kotwal AA, Holt‐Lunstad J, Newmark RL, et al. Social isolation and loneliness among San Francisco Bay Area older adults during the COVID‐19 shelter‐in‐place orders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(1):20‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu J, Son S, McIntyre J, et al. Depression and cardiovascular diseases among Canadian older adults: a cross‐sectional analysis of baseline data from the CLSA comprehensive cohort. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2019;16(12):847‐854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abrams LR, Mehta NK. Changes in depressive symptoms over age among older Americans: differences by gender, race/ethnicity, education, and birth cohort. SSM Popul Health. 2019;7:100399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dying in a leadership vacuum. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1479‐1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Detsky AS, Bogoch II. COVID‐19 in Canada: experience and response. JAMA. 2020;324(8):743‐744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Williams DR, Medlock MM. Health effects of dramatic societal events—ramifications of the recent presidential election. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2295‐2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. The New York Times . 2020; http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html. Accessed August 29, 2020.

- 15. Vogel L. Is Canada ready for the second wave of COVID‐19? Can Med Assoc J. 2020;192(24):E664‐E665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kobayashi LC, O'Shea BQ, Kler JS, et al. Cohort profile: the COVID‐19 Coping Study, a longitudinal mixed‐methods study of middle‐aged and older adults’ mental health and well‐being during the COVID‐19 pandemic in the USA. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e044965. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E‐surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organisation . Women, ageing and health: a framework for action. A Focus on Gender (Report). 2007; http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Women‐ageing‐health‐lowres.pdf.

- 19. Copyright © 2020. Qualtrics and all other Qualtrics product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA. http://www.qualtrics.com.

- 20. Williams II R, Shah A, Tikkanen R, et al. Do Americans face greater mental health and economic consequences from covid‐19? Comparing the US with other high‐income countries. Commonwealth Fund. August 2020. 10.26099/w81v-7659 [DOI]

- 21. Reston M. Governors Dispute Trump's Claim that there's Enough Coronavirus Testing . 2020; http://www.cnn.com/2020/04/19/politics/trump-governors-coronavirus-testing/index.html. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- 22. Barrett K, Khan YA, Mac S, Ximenes R, Naimark DMJ, Sander B. Estimation of COVID‐19–induced depletion of hospital resources in Ontario, Canada. Can Med Assoc J. 2020;192(24):E640‐E646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peters AW, Chawla KS, Turnbull ZA. Transforming ORs into ICUs. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):e52‐e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UKpopulation. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):883‐892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, et al. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324(1):93‐94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shi L, Lu Z‐A, Que J‐Y, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(7):e2014053‐e2014053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dang S, Penney LS, Trivedi R, et al. Caring for caregivers during COVID‐19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(10):2197‐2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vahia IV, Jeste DV, Reynolds CF III. Older adults and the mental health effects of COVID‐19. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2253‐2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Andrews JA, Brown LJ, Hawley MS, et al. Older adults' perspectives on using digital technology to maintain good mental health: interactive group study. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(2):e11694‐e11694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 Text S1: Additional methodology details.

Figure S1: Recruitment flow chart.