Abstract

Objective

Using a mixed‐methods design, we aimed to understand household dynamics and choices in hypothetical planning for child and pet care if an individual is faced with hospitalization for COVID‐19.

Background

As the COVID‐19 public health crisis persists, children and pets are vulnerable to caregiver hospitalization.

Methods

Bivariate associations from a large‐scale survey explore hypothetical options for dependent care‐planning. An open‐ended question regarding pet–child interactions is coded applying a grounded theory framework.

Results

Caregivers expect to rely on family and friends to care for children, especially young children, and pets if hospitalized. The presence of pets in the home has been predominately positive for children during the pandemic, suggesting benefits of alternative care options that keep children and pets together.

Conclusions

Relying on one's social network to care for dependents if caregivers become ill from COVID‐19 could place loved ones at risk for contracting the virus, which could present obstacles to arranging care plans, especially inclusive of pets and children.

Implications

The changing information regarding COVID‐19 warrants that families establish concrete care plans for dependent children and pets. The spread of COVID‐19 to the most vulnerable, such as grandparents and other family who may be expected to care for dependents, could create additional public health concerns.

Keywords: care‐planning for dependents, child care, companion animals, COVID‐19, family, pets

Recent estimates suggest that 60% of U.S. households have pets (Applebaum, Peek, & Zsembik, 2020). Pet owners often consider pets as part of their family (De Coninck et al., 2020; Irvine & Cilia, 2017). Positive interactions and relationships with pets may buffer the negative impacts of stress on well‐being and assist in emotional coping in adverse family situations (Applebaum & Zsembik, 2020; Hawkins et al., 2019). In relation to the COVID‐19 pandemic, if living with pets is beneficial for children as they experience multiple transitions related to COVID‐19, care‐planning that allows pets and children to reside together could reduce stress and provide structure.

Despite potential benefits of having a pet in the home in relation to well‐being (McConnell et al., 2019), the presence of pets may create barriers to accessing health care if alternative pet care is not available from immediate social support networks (Applebaum, Adams, et al., 2020; Canady & Sansone, 2019). Understanding relationships among family structure, inclusive of family pets and available financial and social support resources, can help in supporting families during events such as the COVID‐19 pandemic response.

Given the current public health crisis of the COVID‐19 pandemic, caregivers' perceptions of what they would do for dependents' care if they were hospitalized is a pertinent consideration. Perceptions of risk to alternative caregivers and perceptions of access to financial and social resources may contribute to considerations of alternative care options. Assessing how caregivers expect to find alternative care for dependents when faced with a health emergency can provide information for health practitioners, social workers, and veterinarians; raise awareness of public health concerns; and inform public policy.

We used a mixed‐methods approach to provide a snapshot of how caregivers expect to provide care to dependent children and pets in multispecies households during the COVID‐19 public health crisis. This article includes an exploration of who caregivers might rely on to care for dependent children and provide pet care when caregivers are faced with possible hospitalization due to a positive COVID‐19 diagnosis. Additionally, to understand family life for dependents, we examine how living with pets during the COVID‐19 pandemic has affected children.

methods

Data

An online survey was distributed using the Qualtrics platform through social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Reddit) to various interest groups and accounts related to companion animals, resulting in a nonprobability convenience sample of 2,537 adult pet owners who self‐selected to complete the survey. Given the nature and structure of the survey, we do not expect our sample to contain any duplicate respondents; there were no indentical responses in the dataset. Respondents were not compensated, nor was there a raffle giveaway for particpation, reducing and possibly eliminating incentive to take the survey more than once. We did identify 151 duplicate IP addresses in the Qualtrics system, but due to patterns of missing responses on various variables, the actual number in analyses varies. For example, in analyses for pet‐care decisions, there were only 38 duplicate IP addresses included. We do not expect duplicate IP addresses to be duplicate responses for two reasons. First, Qualtrics has indicated that IP addresses are not a reliable source for determining duplicate responses because it can be different people using the same firewall to access the Internet (such as a university virtual private network). Second, a duplicate IP address can be different people using the same device in a household. We have chosen to retain these 151 duplicate IP addresses in the dataset due to the lack of monetary incentive to participate more than once, and the additional possible explanations for duplicate IP addresses; in this case, a higher sample size is preferable.

Data were collected from April 6, 2020, to May 6, 2020. Respondents were eligible to participate if they were at least 18 years of age and residing in the United States with at least one pet. Informed consent was obtained from each respondent before beginning the survey instrument. Survey topics included questions about respondents' interactions with pets, sociodemographic characteristics, and changes in homelife since the COVID‐19 pandemic began. The survey took approximately 30 minutes to complete. No identifying information was collected from respondents. The survey did not include attention checks; however, given that respondents were aware of not being compensated for their participation before starting the survey, it is reasonable to believe that participants were engaged in survey content. The study protocol was approved by the University of Florida Internal Review Board, protocol # IRB202000819.

Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of 2,537 adult pet owners residing in the United States. The majority of participants were women (89.1%). Participants self‐identified their race and ethnicity as non‐Latinx White (87.8%), non‐Latinx Other (4.8%), Latinx (4.5%), non‐Latinx Multiracial (1.9%), and non‐Latinx Black (1%). The sample's median level of education was a 4‐year college degree. Average age of respondent was 39.3 years (range = 18–85 years; SD = 13.7 years), and 18.1% self‐identified as a caregiver to a child or children.

Quantitative Measures

Dependent variables. Participants responded to questions asking about their plans for the care of their child(ren) (Question 1; only prompted if participants identified dependent children) and pet(s) (Question 2; prompted for all participants) if they were unable to provide care due to COVID‐19–related hospitalization: “Thinking about the current Coronavirus/COVID‐19 situation, what would happen to your child(ren)/pet if you were hospitalized?” Response options for the question related to children were: “Pay for childcare,” “Depend on a family member to take care of my child(ren),” “Depend on a friend or neighbor to take care of my child(ren),” “I don't know,” “Fend for themselves,” and “Other” with a text box for written responses. The “Fend for themselves” category was constructed from text box responses to “Other” regarding responses for children. Responses in the “Other” textbox that did not indicate children caring for themselves in parental absence remained categorized as “Other.” Respondents were prompted to select all responses that applied resulting in non–mutually exclusive categories and six binary variables per question, coded 1 for selected and 0 for not selected. Out of respondents with dependent children, 349 chose one option, 60 chose two options, 28 chose three options, and 20 skipped this question. Response options for pets were as follows: “Pay someone to take care of my pet,” “Depend on a family member to take care of my pet,” “Depend on a friend or neighbor to take care of my pet,” “Relinquish responsibility,” “I don't know,” and “Other” with a text box for written responses. Out of all respondents, 1,266 chose one option, 568 chose two options, and 494 chose three options, 22 chose four options, and 422 people skipped this question.

Demographic variables

Family structure

Due to statistical power considerations for group comparisons, variables were transformed into the following categories: marital status: 1 = married or permanently partnered/cohabitating (unchanged), 2 = single or widowed, and 3 = divorced or separated; children: caregiver to a child or children (1) or not a caregiver (0). Categories were constructed based on family structures that indicate respondents were or were not likely to have another adult in the home who could provide care.

Social support

Respondents completed the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet et al., 1988) to assess their subjective understanding of available supports from various social network members. The scale consisted of 12 questions with 5‐point Likert responses (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree) to assess respondents' degree of agreement with statements about people in their lives, such as “There is a special person who is around when I am in need.” Three subscales for different sources of support were summated separately, representing family (α = 0.92), friends (α = 0.94), and significant other (α = 0.95). Each subscale score ranged from 4 (low) to 20 (high).

Sociodemographic variables

Yearly family income was reported in 26 groups that ranged from “less than $1,000” to “$170,000 or higher.” To consider the rapidly increasing rate of unemployment and difficulty in accessing unemployment benefits in the evolving economic situation in the United States (Cohen & Hsu, 2020), we asked, “Are you worried about losing income due to the COVID‐19 situation?” Response options for worried about income loss were “Yes” (1), “Somewhat” (2), and “No” (3). Respondents also reported their age and their child(ren)'s age, in years; the age of the first‐reported child was included in analyses.

Qualitative Measure

Child–pet interactions during stay‐at‐home orders

Participants who were caregivers of children were invited to respond to one open‐ended question related to how the presence of a pet affected their child(ren) during COVID‐19.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported for each measure (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Information for Sociodemographic and Independent Variables

| Variable | Mean % (n) a | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship status (n = 2,539) | ||

| Married/partnered | 62.70% (1,592) | |

| Single/widowed | 29.81% (757) | |

| Divorced/separated | 7.48% (190) | |

| Parent/caregiver (n = 2,531) | ||

| Has child(ren) | 18.06% (457) | |

| No children | 81.9% (1,074) | |

|

Family income (n = 1,784) Reported median |

$75,000–89,999 |

<$1,000–170,000+ |

| Age (years; n = 1,903) | 39.3 | 18–85 |

| Child's age (years; n = 250) | 10.5 | 0–27 |

| Worried about income loss (n = 1,924) | ||

| Yes | 37.89% (729) | |

| Somewhat | 30.56% (588) | |

| No | 31.55% (607) | |

| Social support: significant other (n = 2,132) | 16.76 | 4–20 |

| Social support: family (n = 2,131) | 15.62 | 4–20 |

| Social support: friends (n = 2,136) | 16.19 | 4–20 |

Column reflects mean except where otherwise noted. Child age ranges from 0–27 due to caregivers reporting young adults as dependent children.

Quantitative

Bivariate associations (chi‐square and t‐tests) are presented to assess the relationships between independent measures and care‐choice selections for children and pets separately. Grouped bivariate analyses by family structure further examine relationships between family structure and hypothetical care choices for dependents.

Qualitative

Initial coding revealed desciptions of benefits (positive effect), problems (negative effect), changes without value or both positive and negative changes (neutral effect), or no changes (no effect, reported as “n/a” or no change) regarding perceptions of child's interaction with pets during stay‐at‐home orders. Coding of the experiences of children in relation to pets was coded based on type of effect followed by the specific nature of the interactions. Two authors coded responses (n = 371; seven were missing or did not answer the stated question) as positive, negative, neutral, or no effect for the child (mutually exclusive) regarding a pet's presence during the pandemic. Then, following a grounded theory approach (Charmaz, 2006), responses were coded using non–mutually exclusive categories that emerged from the responses. Authors selected more than one code when a respondent with a child described more than one benefit or drawback to child–pet interactions, including pet–child interaction, child well‐being, and child development. A third coder with expertise in human–animal interaction helped reach consensus for coder disagreement. Emerging themes from responses to inquiries about child–pet interactions clarify the role of pets for children in the household.

Results

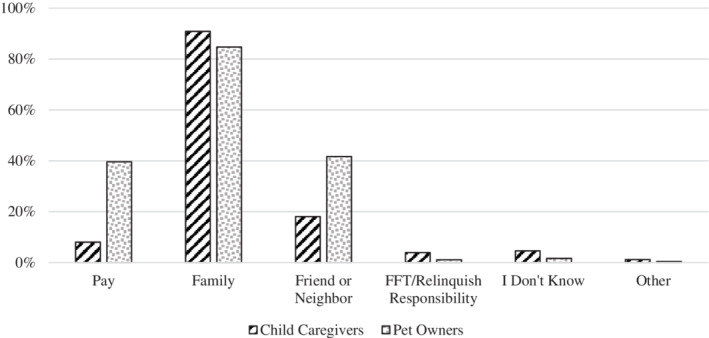

Figure 1 shows that caregivers' most frequent choice for care options for dependent children and pets was family. Participants selected to pay (40%) and rely on friends or neighbors (42%) for pet care. Caregivers to children selected to pay (8%) or rely on friends or neighbors (18%) for childcare.

Figure 1.

Frequencies of Care Choice by Child (n = 437) and Pet (n = 2,350). Note. FFT = fend for themselves.

Child Care‐Planning

As shown in Table 2, a majority of pet owners with children said they would depend on “family” for childcare, and frequency of selecting this choice did not vary significantly across family structure. The mean age of respondents who endorsed that they would rely on a family member was significantly lower, M age = 41.2 years; SD = 8.2, than those who endorsed that they would not rely on a family member, M age = 45.7 years, SD = 7.0; t(336) = 2.96, p = .003. This difference suggests that older parents expect their older children to be capable of taking care of themselves in parental absence. This 4.5‐year age difference in parents reflects a similar age difference between child ages regarding parental hypothetical choice to rely, or not, on family for childcare. The mean child age of caregivers who endorsed that they would rely on a family member was significantly lower, M childage = 10.2 years; SD = 6.6, than those who endorsed that they would not rely on a family member, M childage = 14.6 years, SD = 6.7; t(247) = 2.68, p = .008.

Table 2.

Bivariate Associations for Hypothetical Childcare Choices During COVID‐19

| Pay | Family | Friend | Fend for themselves | Don't know | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship status (n = 436) | ||||||

| Married/partnered | 9.16% | 91.64% | 18.60% | 2.70% | 4.04% | 1.08% |

| Single/widowed | 0.00% | 86.96% | 21.74% | 4.35% | 8.70% | 4.23% |

| Divorced/separated | 2.38% | 85.71% | 11.90% | 14.29% | 7.14% | 0.00% |

| χ2(df = 2) | 4.47 | 2.03 | 1.35 | 13.54 | 1.76 | 2.58 |

| p value | .107 | .363 | .508 | .001 | .414 | .275 |

| Income (n = 321) | ||||||

| “Yes” group M | $110,000–129,999 | $90,000–109,999 | $90,000–109,999 | $75,000–89,999 | $60,000–74,999 | $90,000–109,999 |

| “No” group M | $90,000–109,999 | $90,000–109,999 | $90,000–109,999 | $90,000–109,999 | $90,000–109,999 | $110,000–129,999 |

| t(df = 319) | 1.31 | 0.47 | 0.10 | 1.12 | 1.82 | 0.28 |

| p value | .193 | .638 | .918 | .263 | .070 | .782 |

| Age (n = 338) | ||||||

| “Yes” group M | 36.4 | 41.2 | 40.6 | 46.3 | 39.3 | 47.0 |

| “No” group M | 42.1 | 45.7 | 41.9 | 41.4 | 41.7 | 41.6 |

| t(df = 336) | 3.61 | 2.96 | 1.08 | 2.28 | 1.11 | 1.14 |

| p value | .000 | .003 | .279 | .023 | .269 | .256 |

| Child's age (n = 249) | ||||||

| “Yes” group M | 4.5 | 10.2 | 8.3 | 18.5 | 4.6 | 17.5 |

| “No” group M | 11.2 | 14.6 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 10.8 | 10.5 |

| t(df = 247) | 4.86 | 2.68 | 2.77 | 3.52 | 3.22 | 1.49 |

| p value | .000 | .008 | .006 | .001 | .002 | .137 |

| Worried about income loss (n = 340) | ||||||

| Yes | 8.70% | 89.86% | 23.91% | 2.90% | 5.80% | 1.45% |

| Somewhat | 6.12% | 89.80% | 15.31% | 6.12% | 3.06% | 1.02% |

| No | 10.58% | 94.23% | 15.38% | 3.85% | 3.85% | 0.00% |

| χ2(df = 2) | 1.29 | 1.74 | 3.94 | 1.54 | 1.13 | 1.45 |

| p value | .524 | .419 | .140 | .464 | .568 | .483 |

| Social support: significant other (n = 374) | ||||||

| “Yes” group M | 17.8 | 17.3 | 17.9 | 17.0 | 16.8 | 17.0 |

| “No” group M | 17.2 | 17.2 | 17.1 | 17.3 | 17.3 | 17.3 |

| t(df = 372) | 0.81 | 0.17 | 1.57 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.13 |

| p value | .421 | .868 | .117 | .772 | .607 | .895 |

| Social support: friends (n = 377) | ||||||

| “Yes” group M | 17.0 | 16.4 | 17.2 | 15.4 | 16.8 | 17.0 |

| “No” group M | 16.3 | 16.0 | 16.2 | 16.4 | 16.3 | 16.4 |

| t(df = 375) | 0.96 | 0.45 | 2.23 | 1.04 | 0.46 | 0.30 |

| p value | .337 | .651 | .027 | .298 | .643 | .763 |

| Social support: family (n = 376) | ||||||

| “Yes” group M | 17.3 | 16.4 | 16.7 | 16.6 | 15.8 | 16.0 |

| “No” group M | 16.3 | 16.2 | 16.3 | 16.4 | 16.4 | 16.4 |

| t(df = 374) | 1.37 | 0.35 | 0.74 | 0.16 | 0.74 | 0.20 |

| p value | .172 | .728 | .461 | .875 | .459 | .845 |

Note. Percentage values in cells denote relative frequency of the group that chose “yes” (vs. “no”) for each dependent variable. Bolded text denotes p < 0.05 for χ2 or t test.

Average respondent age for selecting “pay for childcare” was lower, M age = 36.4 years; SD = 6.2, than those who did not select “pay for childcare,” M age = 42.1 years, SD = 8.2; t(336) = 3.61, p = .000; however, average respondent age for selecting “fend for themselves” was higher, M age = 46.3 years, SD = 6.4, than those who did not select this option, M age = 41.4 years, SD = 8.2; t(336) = 2.28, p = .023. Respondents who selected any childcare choice (i.e., “pay,” “family,” or “friends”; exclusive of “fend for themselves” and “other”) or “I don't know” reflected lower child ages, M childage = 4.5 years (SD = 3.7), 10.2 years (SD = 6.6), and 8.3 years (SD = 5.9), respectively, than those who did not select these options, M childage = 11.2 years (SD = 6.6), 14.6 years (SD = 6.7), and 11.1 years (SD = 6.7), respectively, t(247) = 4.86, p = .000, t(247) = 2.68, p = .008, t(247) = 2.77, p = .006. Significantly more respondents who were divorced (14.29%) than married or single (2.7% and 4.35%, respectively), χ2(2) = 13.54, p = .001, chose “fend for themselves.” Taken together, older respondents with older children, as well as divorced persons, more frequently selected “fend for themselves.” This is consistent with timing of divorce, typically occurring later in life when children are older and have more independence.

These associations were explored within subgroups of participants who shared a similar relationship status (i.e., married/partnered, single/widowed, and divorced/separated). Generally, results did not vary from the ungrouped associations provided above. However, there were two differences among divorced respondents: (a) mean level of social support from friends was higher for those who chose “family” for childcare, M score = 17.0, SD = 2.4, than those who did not, M score = 13.4, SD = 5.6; t(34) = 2.52, p = .017; and (b) mean level of social support from friends was lower for those who chose “fend for themselves,” M score = 13.4, SD = 5.6, than those who did not M score = 17.0, SD = 2.4; t(34) = 2.52, p = .017.

Pet Care‐Planning

As shown in Table 3, there were significant differences in pet‐care choices by family structure. All respondents chose “family” for pet care most frequently, but those who were married overwhelmingly endorsed it most frequently (91.7%), compared with single (75.7%) and divorced respondents, 62.2%, χ2(2) = 168.03, p = .000. Divorced respondents chose “friend or neighbor” more frequently (50.0%), compared with those who were single (48.1%) or married (37.5%), χ2(2) = 27.32, p = .000. Respondents without children endorsed “pay” (42.0%) and “friend or neighbor” (43.5%) more frequently than those with children (29.2%), χ2(1) = 23.39, p = .000, and 33.7%, χ2(1) = 13.52, p = .000, respectively), and childless respondents chose “family” (83.3%) less frequently than parents/caregivers (90.9%), χ2(1) = 15.34, p = .000).

Table 3.

Bivariate Associations for Hypothetical Pet‐Care Choices During COVID‐19

| Pay | Family | Friend | Relinquish | Don't Know | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship status (n = 2,345) | ||||||

| Married/partnered | 40.53% | 91.65% | 37.54% | 0.95% | 0.54% | 0.20% |

| Single/widowed | 38.15% | 75.72% | 48.12% | 1.16% | 3.18% | 0.87% |

| Divorced/separated | 37.22% | 62.22% | 50.00% | 1.11% | 3.89% | 0.00% |

| χ2(df = 2) | 1.57 | 168.03 | 27.32 | 0.21 | 27.77 | 6.17 |

| p value | .457 | .000 | .000 | .900 | .000 | .046 |

| Parent/caregiver (n = 2,339) | ||||||

| Has child(ren) | 29.19% | 90.91% | 33.73% | 1.20% | 1.44% | 0.00% |

| No children | 41.96% | 83.29% | 43.52% | 1.04% | 1.67% | 0.47% |

| χ2(df = 1) | 23.39 | 15.34 | 13.52 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 1.97 |

| p value | .000 | .000 | .000 | .780 | .736 | .161 |

| Income (n = 1,782) | ||||||

| “Yes” group M | $75,000–89,999 | $60,000–74,999 | $60,000–74,999 | $40,000–49,999 | $40,000–49,999 | $50,000–59,999 |

| “No” group M | $60,000–74,999 | $75,000–89,999 | $75,000–89,999 | $60,000–74,999 | $60,000–74,999 | $60,000–74,999 |

| t(df = 1,780) | 2.60 | 3.42 | 2.53 | 2.03 | 2.51 | 0.72 |

| p value | .009 | .001 | .011 | .043 | .012 | .472 |

| Age (n = 1,901) | ||||||

| “Yes” group M | 38.4 | 38.5 | 37.4 | 36.4 | 40.1 | 44.2 |

| “No” group M | 39.9 | 43.4 | 40.7 | 39.3 | 39.3 | 39.3 |

| t(df = 1,899) | 2.42 | 5.66 | 5.19 | 0.86 | 0.35 | 0.87 |

| p value | .016 | .000 | .000 | .388 | .728 | .383 |

| Worried about income loss (n = 1,921) | ||||||

| Yes | 41.32% | 84.99% | 45.45% | 0.69% | 1.38% | 0.14% |

| Somewhat | 40.48% | 86.22% | 40.65% | 1.36% | 1.70% | 0.17% |

| No | 41.68% | 82.21% | 42.67% | 0.99% | 2.14% | 0.66% |

| χ2(df = 2) | 0.19 | 3.90 | 3.13 | 1.50 | 1.15 | 3.44 |

| p value | .910 | 142 | .209 | .473 | .564 | .179 |

| Social support: significant other (n = 2,129) | ||||||

| “Yes” group M | 16.9 | 17.0 | 16.9 | 17.9 | 13.3 | 14.1 |

| “No” group M | 16.6 | 15.2 | 16.6 | 16.7 | 16.8 | 16.8 |

| t(df = 2,127) | 1.41 | 7.36 | 1.68 | 1.24 | 4.95 | 1.65 |

| p value | .158 | .000 | .092 | .215 | .000 | .100 |

| Social support: friends (n = 2,133) | ||||||

| “Yes” group M | 16.4 | 16.2 | 16.8 | 16.7 | 14.5 | 14.9 |

| “No” group M | 16.1 | 16.3 | 15.7 | 16.2 | 16.2 | 16.2 |

| t(df = 2,131) | 1.68 | 0.85 | 7.05 | 0.70 | 2.88 | 0.98 |

| p value | .093 | .396 | .000 | .483 | .004 | .329 |

| Social support: family (n = 2,128) | ||||||

| “Yes” group M | 15.4 | 15.9 | 15.5 | 15.1 | 13.8 | 13.4 |

| “No” group M | 15.8 | 13.9 | 15.7 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 |

| t(df = 2,126) | 2.46 | 8.63 | 1.31 | 0.61 | 2.69 | 1.42 |

| p value | .014 | .000 | .190 | .544 | .007 | .155 |

Note. Percentage values in cells denote relative frequency of the groups for each dependent variable. Bolded text denotes p < 0.05 for χ2 or t test.

Generally, family structure was significantly associated with selecting “don't know” for pet care: 3.89% of divorced participants, 3.18% of single participants, and 0.54% of married or partnered participants, χ2(2) = 27.77, p = .000. Those who selected “don't know” for pet care had, on average, lower social support scores across all three dimensions and lower average income than those who did not endorse “don't know.” Income also was significantly associated with all care choices, aside from “other”: Those who selected “family,” “friend or neighbor,” “relinquish,” or “don't know” had lower average income compared with those who did not select these choices; however, those who selected “pay” had higher average income (see Table 3 for t‐test statistics).

We examined grouped bivariate associations by relationship status and report only the grouped bivariate associations that differ from the overall bivariate associations discussed earlier. Among respondents who were married, mean social support from a significant other was higher for those who selected “pay” for pet care, M score = 18.2, SD = 3.2, than those who did not, M score = 17.8, SD = 3.7; t(1,336) = 2.01, p = .045, and those who selected “friend,” M score = 18.4, SD = 3.0, than those who did not, M score = 17.7, SD = 3.8; t(1,337) = 2.25, p = .001. Social support from friends, M score = 16.5, SD = 3.4, was higher for those who indicated “pay” for pet care than those who did not, M score = 16.1, SD = 3.8; t(1,337) = 2.25, p = .025. For those who were single, mean age was higher for those who would pay for pet care, M age = 36.2 years old, SD = 13.7 years, than those who would not, M age = 31.9 years old, SD = 12.1 years; t(553) = 3.85, p = .000. Interestingly, among respondents who were divorced, a higher frequency of those who did not endorse “pay” for pet care also indicated they were not worried about income loss (74.2%) compared with those who would pay for care, 25.8%, χ2(2) = 8.53, p = .017.

Child–Pet Interaction During COVID‐19

About 65% of pet owners with children perceived the presence of household pets to be positive for children, whereas 28% said there was no effect, 2% described a negative effect, and 3% described a neutral effect (n = 371; missing = 7). Parents often described more than one specific way that having pets during COVID‐19 affected their children. Thematic analyses of the written responses demonstrated three themes: (a) child–pet interactions; (b) child emotional well‐being and coping, and (c) assisting in child development.

Child‐Pet Interactions

Of the 371 responses to the open‐ended question, about 55% (n = 206) of parents explained how pets were involved in interactions with their children, 24% (n = 89) of whom specifically noted increased child–pet interaction since children were spending more time at home. Types of interactions include playing with the pet (14%; n = 52); showing pets affection such as cuddling (7%; n = 26); child involvement in pet care (7%; n = 27); and general interaction, such as keeping children busy (3%; n = 12). One parent described the role of pets in the family: “They get to cuddle and pet their cats anytime they need to. They feel a greater sense of ‘family’ because they don't get to hug or be in person with friends right now, but they do with us and our cats” (married, positive).

Child Emotional Well‐Being and Coping

Additionally, caregivers highlighted their perceptions of child emotional well‐being and coping with pets in the home (48%; n = 178). For example, about 20% (n = 76) of child caregivers recounted child expressions of love, happiness, and joy of having pets in the home. Regarding the emotional well‐being of children during the uncertain times of the pandemic, parents elaborated about how having pets were a part of their child(ren)'s general coping and comforting (9%; n = 35), specifically said it mitigated loneliness (8%; n = 30), provided a distraction for the child (6%, n = 21), and reduced child stress or anxiety (4%; n = 16). One parent wrote: “The dog helps our daughter cope so much better than without him. She has something to do, a dog to walk and talk to, which helps with the loss of her friends and playdates” (married, positive). This parent describes improved child coping, and how the child's involvement with the pet helps the child since she is unable to interact with peers.

Child Development

The final theme parents described were ways that having a pet during the pandemic affected children developmentally (14%; n = 54). Parents explained how the presence of pets allowed children to spend more of their time taking over pet‐related responsibilities that parents once performed (e.g., feeding; 5%; n = 18); created an opportunity for understanding pet boundaries (4%; n = 15); provided structure or routine to children's days (∼3%; n = 10); and increased exercise for children (∼2%; n = 7). For example, caregivers highlight increased responsibility related to pets: “My daughter spends hours holding, talking to, and petting her 5 [month‐]old kitten. She has been doing more care of her kitten (feeding and cleaning litter box)” (married, positive). The majority of caregivers detailed how pets benefited families overall, and notably children, during this unprecedented time.

Negative Descriptions of Child–Pet Interactions

Several pet owners (2%, n = 7) noted difficulties for children adjusting to increased time at home with pets. Five of the seven parents explained that children were annoying pets or intiating interactions with pets that the pet did not want. One parent wrote: “The 5‐year‐old has started chasing and trapping the cats again. He's regressed back to some negative behaviors that were fixed years prior to the quarantine” (married, negative). Another parent simply stated that children and pets were bored in quarantine, and another said their child was jealous that the cats prefer the parent because the cats are not accustomed to seeing the child at home so much. Although a small portion of caregivers described negative effects of child–pet interactions during stay‐at‐home orders, these outliers suggest variation in the experience of children's and pets' adjustment to spending more time together.

Discussion

Our results indicate that those who did not know what they would do for pet care tended to have lower income, were unmarried/unpartnered, and had less social support. This has implications for animal welfare because lower resourced pet owners may be forced to relinquish their pets to animal shelters if they do not have other options (Guenther, 2020). Combined with the looming eviction crisis (Benfer et al., 2020), shelter intake and subsequent euthanasia are expected to rise as a result of the financial fallout of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Most respondents chose family for care of both pets and children; however, a significantly higher frequency of pet owners without children than those with children chose friend or neighbor or pay for pet care, and a significantly larger proportion of parents chose family for care. Neither pet owners with children nor pet owners without children were willing to absolve themselves of responsibility for their dependents, despite both groups possibly struggling with scarcity of social and financial resources for their dependent.

Differences in hypothetical care choices between pet owners with and without children reflect norms of dependent care and development. For example, long‐term care for children in the United States is not a common service option, and it would be exorbitantly expensive, making it unrealistic as an option for up to a month of care during COVID‐19 hospitalization (Gupta et al., 2020). Speculatively, pet owners with children or grandchildren may reside closer to family to help with childcare on a regular basis (Diepen & Mulder, 2009; Mulder & Cooke, 2009), and expect to rely on them in a health emergency, although grandparent–grandchild contact can vary by family structure and residence arrangements (Jappens & Van Bavel, 2016). Pet owners without children may live farther from family and expect to rely on friends who live close to them or rely on affordable long‐term pet‐care options, such as private in‐home pet services, or boarding services. Pets, even when considered members of the family, may not illicit closer proximity to family, although this is an unexplored empirical topic. Additionally, as children age, it is expected that they become increasingly independent in preparation for adulthood, allowing caregivers of older children to no longer need alternative‐care options, such as the idea that children can fend for themselves during hypothetical parental hospitalizations indicated by participants. Older pets, on the other hand, often need more care, which could contribute to more work than a family member or friend can provide, especially alongside the care of a young child.

Due to the nature of our data, we were unable to determine whether those with both children and pets would intend to rely on the same person or people for care simultaneously. However, given our findings as one of the first multispecies studies examining care decisions and previous literature that children tend to benefit from being with pets during stressful circumstances (Melson, 2003), this has important implications regarding caregiver burden. It is possible that relying on a grandparent for care of both pets and children could be unrealistic, especially given changes to everyday life to prevent the spread of COVID‐19 (e.g., fewer options for entertaining children, more time in close contact with pets). Those who do not have previous experience managing children and pets together could put their household at increased risk of injuries from pets, such as dog bites, when the caregiver is otherwise occupied or unaware of appropriate child–pet interactions.

It is important to note that caregiver perceptions of pets' presence on children were identified as mostly beneficial in child–pet interactions and child well‐being. This suggests that it may be beneficial to keep children and pets together during alternative‐care situations. However, parents who noted negative consequenecs of the presence of pets to children highlight that more time between children and pets is not always positive, especially as children spend more time at home. As education moved from schools into home environments to reduce viral spread in March 2020 and again as the 2020–2021 school year began (although with variation in and between states), children's attention at home requires focus on virtual schooling, creating opportunities for pets to become problematic. Therefore, our findings support that planning for caregivers' health care necessitates considering the benefits and drawbacks of keeping children and pets together for child well‐being during caregiver absence.

Implications and Limitations

Possibilities for alternative care‐planning for dependents during a public health emergency could routinely include health care practitioners asking patients about family structure, inclusive of pets, so that practitioners can initiate care planning and are aware of potential obstacles to providing care to patients. Veterinarians could provide a form to complete upon the initial visit that systematically encourages pet owners to provide care details if something happens to the owner. For high‐risk pet owners and dependent child caregivers, such as elderly care providers, veterinarians and social workers could partner to address community needs in preparation for health emergencies, specifically public health emergencies that can alter the care plan (Rauktis & Hoy‐Gerlach, 2020). Making temporary animal boarding or foster shelter locations affordable and available to hospitalized pet owners, similar to models deployed during disasters (e.g., ASPCA's Field Response program), or providing financial assistance for emergency boarding (e.g., redrover.org) to address animal needs could alleviate some difficulties for pet owners (with and without children), who need pet care and may not be able to keep children and pets together.

As efforts to contain the spread of COVID‐19 and its effects on society continue, it is important to consider how families will navigate the incapacitation of a caregiver, especially when another adult who can care for dependents does not reside in the home. The severity of symptoms, hospitalizations, and lasting consequences of COVID‐19 contribute to public health officials' concerns over reducing the spread of the virus. Although this is a convenience sample, research indicates that current family demographic trends show a delay in, or forgoing of, childbearing among higher educated women with higher incomes (Koropeckyj‐Cox & Call, 2007). In some cases, women choose an animal companion for the fulfillment of nurturing instead of adding human children to their family (Laurent‐Simpson, 2017) strengthening the need to incorporate pets into care planning for dependents. Research with multispecies families, and especially families with both children under age 18 and pets, is needed to consider variation in care needs and options of dependents in health emergencies. Despite limitations of a disproportionately White, highly educated, female sample, these findings highlight the need for families to plan for public health emergencies and hospitalization of a caregiver, coordinating care plans that address the holistic family unit with human and animal dependents.

Conclusion

In this study, we examined how pet owners think about care planning for both dependent children and pets during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Our findings indicate that caregivers expect to rely on their closest social support systems to care for dependents if they become ill from COVID‐19; however, expecting to rely on loved ones who could contract the virus could present obstacles to arranging care plans, especially inclusive of pets and children. Recently, the New York Times reported how pets were in homes of residents who were suddenly hospitalized with COVID‐19 without care, and only natural disaster officials with protective equipment could safely enter a home where a human tested positive (Nir, 2020). In instances where adults contract the virus but children do not or only experience mild symptoms, it is crucial that there is a concrete, executable plan in place for dependents to be cared for. Given the emotional consequences of isolation for everyone, but especially for children, and the benefits of having pets that parents describe here, integrating care‐planning to keep children and pets united could minimize additional disruption if a caregiver is incapacitated during a health emergency.

author note

Many thanks to Camie Tomlinson, Angela Matijczak, Jennifer Murphy, and Laura Booth for their assistance in the creation of and recruitment for this survey.

references

- Applebaum, J. W. , Adams, B. L. , Eliasson, M. N. , Zsembik, B. A. , & McDonald, S. E. (2020). How pets factor into healthcare decisions for COVID‐19: A one health perspective. One Health, 100176. 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum, J. W. , Peek, C. W. , & Zsembik, B. A. (2020, March). Examining U.S. pet ownership using the General Social Survey. The Social Science Journal, 1–10. 10.1080/03623319.2020.1728507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum, J. W. , & Zsembik, B. A. (2020). Pet attachment in the context of family conflict. Anthrozoös, 33(3), 361–370. 10.1080/08927936.2020.1746524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benfer, E. , Bloom Robinson, D. , Butler, S. , Edmonds, L. , GIlman, S. , Lucas McKay, K. , Neumann, Z. , Owens, L. , Steinkamp, N. , & Yentel, D. (2020). The COVID‐19 eviction crisis: An estimated 30–40 million people in America are at risk. The Aspen Institute. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/blog‐posts/the‐covid‐19‐eviction‐crisis‐an‐estimated‐30‐40‐million‐people‐in‐america‐are‐at‐risk/ [Google Scholar]

- Canady, B. , & Sansone, A. (2019). Health care decisions and delay of treatment in companion animal owners. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 26(3), 313–320. 10.1007/s10880-018-9593-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, P. , & Hsu, T. (2020). Unemployment claims above 36 million in coronavirus pandemic. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/14/business/economy/coronavirus‐unemployment‐claims.html

- De Coninck, D. , Matthijs, K. , & Dekeyser, G. (2020). What's in a Family? Family Conceptualizations of Flemish College‐Aged Students (1997–2018). Family Relations. Advance online publication. 10.1111/fare.12433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diepen, A. M. L. , & Mulder, C. H. (2009). Distance to family members and relocations of older adults. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 24(1), 31–46. 10.1007/s10901-008-9130-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther, K. M. (2020). The lives and deaths of shelter animals. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S. , Hayek, S. S. , Wang, W. , Chan, L. , Mathews, K. S. , Melamed, M. L. , … Leaf, D. E. , for the STOP‐COVID Investigators . (2020). Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(11), 1436–1446. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, R. D. , McDonald, S. E. , O'Connor, K. , Matijczak, A. , Ascione, F. R. , & Williams, J. H. (2019). Exposure to intimate partner violence and internalizing symptoms: The moderating effects of positive relationships with pets and animal cruelty exposure. Child Abuse & Neglect, 98, 104166. 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2019.104166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, L. , & Cilia, L. (2017). More‐than‐human families: Pets, people, and practices in multispecies households. Sociology Compass, 11(2), e12455. 10.1111/soc4.12455 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jappens, M. , & Van Bavel, J. (2016). Parental divorce, residence arrangements, and contact between grandchildren and grandparents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(2), 451–467. 10.1111/jomf.12275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koropeckyj‐Cox, T. , & Call, V. R. A. (2007). Characteristics of older childless persons and parents. Journal of Family Issues, 28(10), 1362–1414. 10.1177/0192513X07303837 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent‐Simpson, A. (2017). “They make me not wanna have a child”: Effects of companion animals on fertility intentions of the childfree. Sociological Inquiry, 87(4), 586–607. 10.1111/soin.12163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, A. R. , Paige Lloyd, E. , & Humphrey, B. T. (2019). We are family: Viewing pets as family members improves wellbeing. Anthrozoös, 32(4), 459–470. 10.1080/08927936.2019.1621516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melson, G. F. (2003). Child development and the human–companion animal bond. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(1), 31–39. 10.1177/0002764203255210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, C. H. , & Cooke, T. J. (2009). Family ties and residential locations. Population, Space and Place, 15(4), 299–304. 10.1002/psp.556 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nir, S. M. (2020, June 23). The pets left behind by COVID‐19. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/23/nyregion/coronavirus‐pets.html [Google Scholar]

- Rauktis, M. E. , & Hoy‐Gerlach, J. (2020). Animal (non‐human) companionship for adults aging in place during COVID‐19: A critical support, a source of concern and potential for social work responses. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(6–7), 702–705 10.1080/01634372.2020.1766631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G. D. , Dahlem, N. W. , Zimet, S. G. , & Farley, G. K. (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]