Abstract

A serological survey of human coronavirus antibodies among villagers in 10 provinces of Thailand was conducted during 2016–2018. Serum samples (n = 364) were collected from participants from the villages and tested for coronavirus antibodies using a human coronavirus IgG ELISA kit. Our results showed that 10.44% (38/364; 21 males and 17 females) of the villagers had antibodies against human coronaviruses. The odds ratio for coronavirus positivity in the villagers in the central region who were exposed to bats was 4.75, 95% CI 1.04–21.70, when compared to that in the non‐exposed villagers. The sociodemographics, knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) of the villagers were also recorded and analysed by using a quantitative structured questionnaire. Our results showed that 62.36% (227/364) of the villagers had been exposed to bats at least once in the past six months. Low monthly family income was statistically significant in increasing the risk for coronavirus seropositivity among the villagers (OR 2.91, 95% CI 1.13–7.49). In‐depth interviews among the coronavirus‐positive participants (n = 30) showed that cultural context, local norms and beliefs could influence to bat exposure activities. In conclusion, our results provide baseline information on human coronavirus antibodies and KAP regarding to bat exposure among villagers in Thailand.

Keywords: bat, coronavirus, seroprevalence, Thailand, villagers

Impacts.

A serological survey of human coronavirus antibodies among villagers in 10 provinces of Thailand during 2016–2018 showed that 10.44% (38/364) of the villagers had antibodies against human coronaviruses.

The odds ratio for coronavirus positivity in the villagers in the central region who were exposed to bats was 4.75 (95% CI 1.04–21.70) compared to that for the non‐exposed villagers.

Our results showed that 62.36% (227/364) of the villagers had been exposed to bats at least once in the past six months. Low monthly family income was statistically significant in increasing the risk for coronavirus seropositivity among the villagers.

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus (CoV), an enveloped, positive‐sense, single‐stranded RNA virus, belongs to the family Coronaviridae. There are four genera of CoVs, namely, alphacoronavirus, betacoronavirus, gammacoronavirus and deltacoronavirus. Betacoronavirus can be further classified into 4 subgenera: lineage A (Embecovirus), lineage B (Sarbecovirus), lineage C (Marbocovirus) and lineage D (Nobecovirus). CoVs have been reported to infect humans and several animal species, causing mild to severe respiratory and enteric diseases. Human coronavirus (HCoV) was first reported in the mid‐1960s (Kendall et al., 1962). Currently, there are at least four HCoVs, namely, alphacoronavirus (229E, NL63) and betacoronavirus (OC43, HKU1) (Osborne et al., 2011). Moreover, three betacoronaviruses causing emerging severe respiratory diseases in humans are SARS‐CoV, MERS‐CoV and SARS‐CoV‐2. SARS‐CoV causes epidemic Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), with an overall mortality rate of 10%. SARS‐CoV was reported to originate from horseshoe bats as reservoirs and palm civet cats as an intermediate host in China (Lau et al., 2005). MERS‐CoV causes Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in more than 20 countries with a high mortality rate of 35% (Chan et al., 2015). MERS‐CoV is closely related to CoVs from bats and dromedary camels (Crameri et al., 2015). Recently, the novel coronavirus SARS‐CoV‐2 caused an emerging pandemic disease, COVID‐19, in late 2019 (Li et al., 2020). The virus was speculated to originate from bats in China and unproven intermediate host (Lam et al., 2020). As of October 2020, the COVID‐19 pandemic has been reported in more than 180 countries with an approximately 2.7% mortality rate (WHO, 2020).

Bats are important reservoirs for several viral pathogens, including rabies virus, Nipah virus, Ebola virus, SARS‐CoV, MERS‐CoV and emerging SARS‐CoV‐2 (Dato et al., 2016; Han et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2020; Sazzad et al., 2013; Zaki et al., 2012; Zhou, Chen, et al., 2020; Zhou, Yang, et al., 2020). In Thailand, betacoronavirus was detected in bat guano collected from a cave in 2006–2007 (Wacharapluesadee et al., 2013). However, the human behaviours that facilitate exposure to bats remain unknown. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine coronavirus seroprevalence among villagers exposed to bats in 10 provinces of Thailand during November 2016–May 2018. The exposure behaviours, knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) of the villagers were also evaluated.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Blood sample collection from villagers

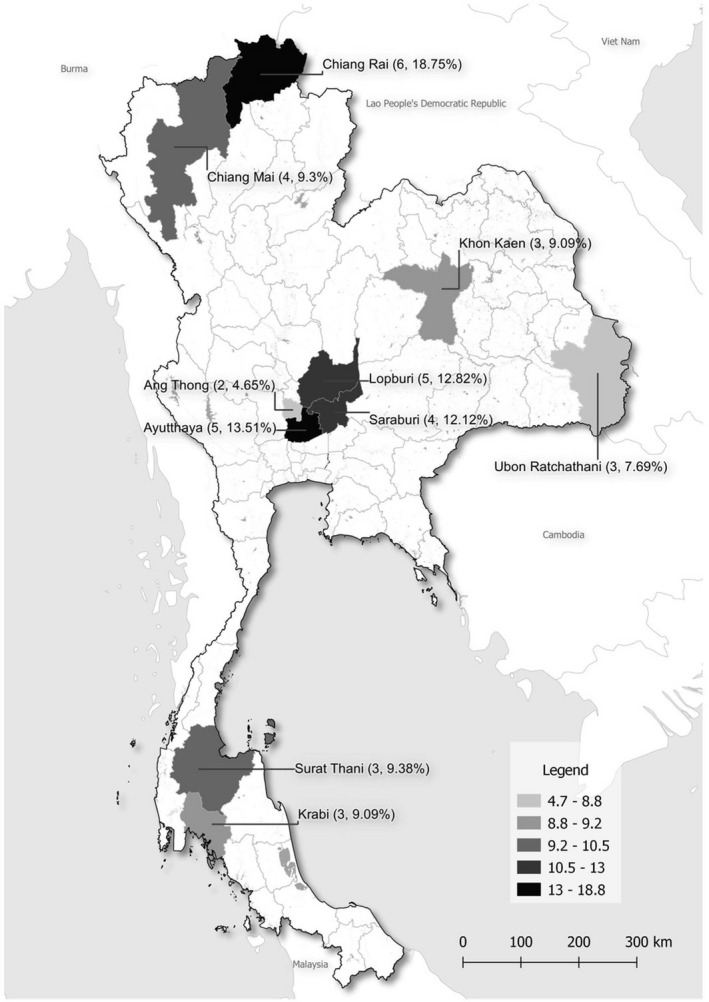

An analytic cross‐sectional serological survey was conducted to determine coronavirus seroprevalence among villagers aged between 20 and 75 years old in 10 provinces within four regions of Thailand from November 2016 to May 2018. The study sites were purposively selected based on information from the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP), Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MNRE) and Ministry of Public Health (MoPH). Scoping visits were conducted to determine potential study sites where the villagers’ residences were in or near areas of high bat density. In this study, study sites in 10 provinces representing the four regions of Thailand were chosen for sample and data collection (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Map of study provinces in Thailand and percentages of CoV seropositivity among villagers

Blood samples (5 ml) were collected from 364 participants who agreed to participate in both blood testing and questionnaire interviews for a quantitative study. The study participants were recruited based on the following criteria: (a) participants aged between 20 and 75 years old, (b) participants living in the study sites at least six months before data and sample collection, and (c) participants willing to participate in both blood testing and questionnaire interviews. Simple random sampling (SRS) was utilized to select the participants from the household registries at the local health offices in the communities. Approximately 30–35 participants from each village were included in the study. The study was conducted under the approval of Chulalongkorn University IRB and Chiang Rai Provincial Health Office (No. 034.1/59, No. 208.1/60 and 26/2559). Written informed consent forms were obtained from the participants before the interviews and blood collection.

2.2. Human coronavirus antibodies detection by ELISA

The serum samples (n = 364) were prepared and processed at the Center of Excellence for Clinical Virology, Chulalongkorn University. A human coronavirus IgG ELISA kit (ABBEXA) was used to test for human coronavirus antibodies following the manufacturer's recommendations. In brief, 50 μl of negative/positive controls or test samples were added to the appropriate wells and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After incubation, the plate was washed with 300 μl of 1× wash buffer in each well 5 times. Then, 100 μl of HRP was added to each well (except the blank well) and inoculated at 37°C for 60 min. After incubation, the plate was washed 5 times with 300 μl of 1× wash buffer in each well. Then, 50 μl of TMB substrate A and 50 μl of TMB substrate B were added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. After incubation, 50 μl of stop solution was added to stop the reaction. The O.D. absorbance was measured by spectrophotometry at 450 nm. The cut‐off value was calculated (negative control + 0.15). If the O.D. of the sample was < the cut‐off, the test sample was considered negative. If the O.D. of the sample was ≥ the cut‐off, the test sample was considered positive for human coronavirus IgG.

2.3. Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) analysis by a quantitative structural questionnaire

Data collection procedures to collect information on sociodemographics, exposure behaviours, knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) of the villagers were carried out by using a standardized structural quantitative questionnaire. The questionnaire was modified from previous studies and refined per the pre‐tested results with 30 participants in an area with a similar population and environment as the actual study sites (Suwannarong & Chapman, 2014; Suwannarong et al., 2015). Trained field researchers conducted face‐to‐face interviews using the questionnaire.

Sociodemographic (SES; 5 variables), knowledge, attitude and practice variables (KAP; 9 variables) were analysed to determine the possible factor associations of bat exposure and coronavirus antibody positivity. Data from the questionnaire were entered into a database and analysed with SPSS software version 22. After data cleaning, the dependent (coronavirus antibody positivity) and independent analytical variables were created. Data were analysed in 3 steps. First, descriptive analysis was conducted to provide frequencies and percentages of each variable. The second step included bivariate analysis, in which the degree of association between the dependent variable was computed, and each of the independent variables was ascertained separately. The final step utilized a stepwise logistic regression model that used p ≤ .05 as a cut‐off point for statistical significance.

2.4. Factors related to coronavirus positivity analysis by qualitative in‐depth interviews

A qualitative study using in‐depth interviews among those who had positive coronavirus antibodies (n = 30) was carried out. In this study, 30 participants with positive coronavirus antibodies agreed to participate in the interviews. Trained qualitative facilitators conducted the interviews during October 2018 – February 2019 to obtain comprehensive information on bat exposure and possible factors or activities correlated with coronavirus positivity.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Seroprevalence of human coronavirus among the villagers

Among 364 villagers, 10.44% (n = 38; 21 males and 17 females) had antibodies against human coronavirus. By region, the seropositive individuals were from central regions (16, 42.11%), followed by northern (10, 26.31%), northeastern (6, 15.79%) and southern regions (6, 15.79%). By province, the highest seropositivity was found in Chiang Rai (18.75%), followed by Ayutthaya (13.51%), Lopburi (12.82%), Saraburi (12.12%) and Chiang Mai provinces (9.30%; Table 1 and Figure 1).

TABLE 1.

Seroprevalence of coronavirus (CoV) among villagers in 10 provinces of Thailand

| Province | Region | No. of Participants | No. of Seropositive (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chiang Mai | Northern | 43 | 4 (9.30%) |

| Chiang Rai | Northern | 32 | 6 (18.75%) |

| Ayutthaya | Central | 37 | 5 (13.51%) |

| Ang Thong | Central | 43 | 2 (4.65%) |

| Lopburi | Central | 39 | 5 (12.82%) |

| Saraburi | Central | 33 | 4 (12.12%) |

| Khon Kaen | Northeastern | 33 | 3 (9.09%) |

| Ubon Ratchathani | Northeastern | 39 | 3 (7.69%) |

| Krabi | Southern | 33 | 3 (9.09%) |

| Surat Thani | Southern | 32 | 3 (9.38%) |

| Total | 364 | 38 (10.44%) | |

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Of 38 seropositive villagers, 24 (63.16%) reported exposure to bats by direct and indirect activities. The odds ratio of coronavirus seropositivity among the villagers who reported exposure to bats and non‐exposure to bats was 1.04, 95% CI 0.52–2.08, but was not statistically significant (p = .91). Analysis by region showed that the odds ratio of coronavirus seropositivity among the villagers in the central region was 4.75 (95% CI 1.04–21.70, p‐value .04), suggesting that the villagers in central Thailand who were exposure to bats were more likely to have coronavirus antibodies (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Association measurements (odds ratios) of coronavirus seropositivity among villagers who were exposed and non‐exposed to bats in Thailand by region

| Region | Coronavirus seropositive | Coronavirus seronegative | Total | OR | 95% CI | p‐Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central (n = 152) | Exposure to bats | 14 | 82 | 95 | |||

| Non‐exposure to bats | 2 | 54 | 57 | ||||

| 16 | 136 | 152 | 4.75 | 1.04–21.70 | .04* | ||

| Northern (n = 75) | Exposure to bats | 4 | 44 | 48 | |||

| Non‐exposure to bats | 6 | 21 | 27 | ||||

| 10 | 65 | 75 | 0.32 | 0.08–1.25 | .10 | ||

| Northeastern (n = 72) | Exposure to bats | 2 | 43 | 45 | |||

| Non‐exposure to bats | 4 | 23 | 27 | ||||

| 6 | 66 | 72 | 0.27 | 0.05–1.57 | .14 | ||

| Southern (n = 65) | Exposure to bats | 4 | 35 | 39 | |||

| Non‐exposure to bats | 2 | 24 | 26 | ||||

| 6 | 59 | 65 | 1.37 | 0.23–8.09 | .73 | ||

| Total (n = 364) | Exposure to bats | 24 | 204 | 227 | |||

| Non‐exposure to bats | 14 | 122 | 137 | ||||

| 38 | 326 | 364 | 1.04 | 0.52–2.08 | .91 |

Statistically significant at p ≤ .05.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

3.2. Knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) among the villagers

In this study, 364 participants (191 males and 173 females) from 14 districts of 10 provinces were randomly selected and interviewed to gather information on bat exposure activities. Among 364 participants, 227 persons (62.36%) reported bat contact at least once time within six months before the data collection (Table 2). Sociodemographic information among the 38 coronavirus seropositive individuals included the following: the mean age of the villagers was 45.55 years old (25–70 years old), 55.26% (21/38) were married, 57.89% (22/38) had an education lower than secondary schools, and 84.21% (32/38) had a low monthly family income <15,000 THB per month (450 USD; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Bivariate analysis of sociodemographic and knowledge, attitude and practice characteristics with coronavirus seropositivity among villagers in Thailand

| Variables a | Coronavirus seropositive | Coronavirus seronegative | OR | 95% CI | p‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic information | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 21 | 170 | |||

| Female | 17 | 156 | |||

| 1.13 | 0.58–2.23 | .74 | |||

| Age group | |||||

| <50 years | 24 | 164 | |||

| >50 years | 14 | 162 | |||

| 1.69 | 0.85–3.39 | .17 | |||

| Occupation | |||||

| Agriculture related occupation | 14 | 106 | |||

| Other occupation | 24 | 220 | |||

| 1.21 | 0.60–2.44 | .59 | |||

| Educational attainment | |||||

| <Secondary school level | 22 | 196 | |||

| >Secondary school level | 16 | 130 | |||

| 0.91 | 0.46–1.80 | .86 | |||

| Family monthly income | |||||

| <15,000 THB | 32 | 221 | |||

| ≥15,000 THB | 6 | 105 | |||

| 2.53 | 1.03–6.25 | .04* | |||

| Knowledge, attitude and practice information | |||||

| People can get diseases from bats (positive KAP) | |||||

| Agree | 21 | 181 | |||

| Disagree | 17 | 145 | |||

| 0.99 | 0.50–1.95 | 1.00 | |||

| We can get diseases if we eat leftover fruits from bats (positive KAP) | |||||

| Agree | 20 | 195 | |||

| Disagree | 18 | 131 | |||

| 0.75 | 0.38–1.47 | .49 | |||

| I feel no concerns about getting diseases from bats (negative KAP) | |||||

| Disagree | 7 | 61 | |||

| Agree | 31 | 265 | |||

| 0.98 | 0.41–2.33 | 1.00 | |||

| I feel safe live in or near bat areas (negative KAP) | |||||

| Disagree | 16 | 152 | |||

| Agree | 22 | 174 | |||

| 0.83 | 0.42–1.64 | .61 | |||

| Bat guano is safe to use (negative KAP) | |||||

| Disagree | 8 | 56 | |||

| Agree | 30 | 270 | |||

| 1.29 | 0.56–2.95 | .51 | |||

| Bats are economically beneficial to the community (positive KAP) | |||||

| Agree | 18 | 172 | |||

| Disagree | 20 | 154 | |||

| 0.81 | 0.41–1.58 | .61 | |||

| It is safe to eat bats (negative KAP) | |||||

| Disagree | 13 | 113 | |||

| Agree | 25 | 213 | |||

| 0.98 | 0.48–0.199 | 1.00 | |||

| It is fine to hunt bats for consumption (low enforcement related) | |||||

| Disagree | 14 | 129 | |||

| Agree | 24 | 197 | |||

| 0.89 | 0.44–1.79 | .86 | |||

| It is okay to bring dead bats home for food (negative KAP) | |||||

| Disagree | 34 | 282 | |||

| Agree | 4 | 44 | |||

| 1.33 | 0.45–3.92 | .80 | |||

Variables: 5 SES variables and 9 KAP variables.

Cut‐off point for stepwise logistic regression at p < .05.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Knowledge, attitudes and practices analysis among the 38 coronavirus seropositive villagers showed that the participants understood that people could get any diseases from bats (21, 55.26%) and that people could get diseases if they eat leftover fruits from bats (20, 52.63%). However, some participants had incorrect KAP that they felt no concern about getting diseases from bats (31, 81.58%) and felt safe to be in areas where bats lived (22, 28.95%). It is fine to hunt bats for consumption (24, 63.16%), and it is safe to eat bats (25, 65.78%). The results from the bivariate analysis showed that only one variable (low family monthly income (<15,000 THB, 450 USD) was statistically significant (p‐value .04). Per the stepwise logistic regression, low family monthly income (<15,000 THB; OR 2.91, 95% CI 1.13–7.49, p‐value .03) was statistically significant for coronavirus seropositivity (Table 4). Our results suggested that the villagers with low family income were 2.91 times more likely to be coronavirus positive than those with higher family income.

TABLE 4.

A stepwise logistic regression model among coronavirus seropositive villagers in Thailand

| Variable | Coefficient | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic information | ||||

| Sex (male) | 0.18 | 1.19 | 0.58–2.45 | .63 |

| Age group (<50 years) | 0.59 | 1.82 | 0.86–3.86 | .12 |

| Occupation (agriculture related occupation) | 0.30 | 1.35 | 0.65–2.82 | .42 |

| Educational attainment (<secondary school level) | −0.17 | 0.84 | 0.39–1.82 | .66 |

| Family monthly income (<15,000 THB) | 1.07 | 2.91 | 1.13–7.49 | .03* |

| Knowledge, attitude and practice information | ||||

| People can get diseases from bats (Agree) | 0.73 | 1.08 | 0.49–2.37 | .86 |

| We can get diseases if we eat leftover fruits from bats (Agree) | −0.28 | 0.76 | 0.35–1.63 | .48 |

| I feel no concerns about getting diseases from bats (Disagree) | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.42–2.59 | .93 |

| I feel safe live in or near bat areas (Disagree) | −0.25 | 0.78 | 0.38–1.58 | .49 |

| Bat guano is safe to use (Disagree) | 0.18 | 1.19 | 0.49–2.91 | .69 |

| Bats are economically beneficial to the community (Agree) | −0.12 | 0.89 | 0.44–1.81 | .74 |

| It is safe to eat bats (Disagree) | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.49–2.29 | .88 |

| It is fine to hunt bats for consumption (low enforcement related; Disagree) | −0.28 | 0.76 | 0.37–1.57 | .46 |

| It is okay to bring dead bats home for food (Disagree) | 0.48 | 1.62 | 0.52–4.99 | .40 |

Statistically significant at p < .05.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

3.3. A qualitative study on bat exposure activities among the seropositive villagers

For the qualitative study, we conducted in‐depth interviews with 30 participants (15 females and 15 males) who had coronavirus seropositivity and agreed to participate in the study. The missing participants died due to a motorcycle accident (n = 1) or liver‐ and kidney‐related diseases (n = 2). Other individuals (n = 5) were not available for the interviews due to working in other provinces. Twenty‐three of the 30 participants (76.7%) reported exposure to bats directly and indirectly in their lifetime; for example, hunting, consumption, bitten, collecting bat guano, mining bat guano, and preparing bat meat for food. Some participants reported their illness in the past ten years, such as unknown high fever (10, 33.33%), asthma (2, 6.67%) and numbness in the hands and legs (1, 3.33%). Seven out of 30 participants reported that they had not been exposed to bats. Some participants were not exposed to bats due to the belief that bats are the animals of holy Buddha statues and should not be harmful. Our findings suggested that religion, cultural contexts, local norms and beliefs might be influencing factors related to the bat exposure activities of the villagers.

4. DISCUSSION

Four strains of coronavirus (229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1) have been described to infect humans, causing mild to severe respiratory disease (Arden et al., 2005; Dare et al., 2007; Esper et al., 2005; Lau et al., 2006). HCoV‐229E (group I) and HCoV‐OC43 (group II) were first reported in the 1960s (Hamre & Procknow, 1966). Then HCoV‐NL63 (group I) and HCoV‐HKU1 (group II) were identified in 2004–2005 after the SARS outbreak. It has been speculated that HCoVs might infect the human population for a long time, thus, the seroprevalence of HCoV would be high. Several studies reported serum antibodies to four HCoVs in healthy children and adults. For example, a study in the Netherlands reported 65%–75% of antibodies against HCoV‐229E and HCoV‐NL63 in children. A previous study showed that serum IgG against HCoV‐229E developed after 8 days and peaked at 14 days after infection. The antibody level declined between 11 and 54 weeks (Callow et al., 1990; Huang et al., 2020). In Thailand, HCoV‐OC43 was predominantly detected in HCoV‐infected patients (Dare et al., 2007). Our results showed that approximately 10.44% of 364 villagers had antibodies against human coronavirus. This current seroprevalence is higher than that of previous studies (Chan et al., 2009; Leung et al., 2006). It should be noted that ELISA test kit detects HCoV IgG but less cross reacts to antibodies against SARS‐CoV, MERS‐CoV and SAR‐CoV‐2.

In this study, 24 out of 38 (63.16%) seropositive villagers reported exposure to bats by direct and indirect activities. The villagers had been exposed to bats in several ways such as contact with live and dead bats, mining/collecting/cleaning/using bat guano, and being bitten by bats. The current results were consistent with a previous study in Thailand in which activities related to bat guano (e.g. cleaning, mining, collecting and selling as fertilizer) were considered high‐risk activities (Suwannarong & Schuler, 2016). Moreover, betacoronavirus group C has been detected in bat guano in Thailand and possibly caused CoV infection in humans (Wacharapluesadee et al., 2013). To our knowledge, this study is the first to report CoV seropositivity among villagers who live in or near areas of high bat density in Thailand. Nevertheless, its limitation was that sources of CoV infection among the villagers could not be definitely identified since the villagers had been exposed to other domestic animals aside from bats.

The quantitative study results showed that low monthly family income (<15,000 THB (450 USD) was a statistically significant risk factor. Our results implied that people with lower incomes have a greater chance of exposure to bats and coronavirus seropositivity. For example, villagers can hunt bats for consumption or had been exposed to bats in community forests. In contrast, a study in Vietnam reported that wildlife consumption was considered a luxury activity (Sandalj et al., 2016). Our results also showed that the villagers were not aware of possible disease risks from close contact with bats, which might lead them to have more exposure activities to bats and be prone to CoV infection. Several studies have reported that bats are hunted for several purposes, such as food, medicine, special ceremonies and traditional celebrations (Mildenstein et al., 2016). It has been reported that the bat population is decreasing due to bat hunting for sustenance and sports, especially in the Southeast Asian region, even though bat hunting is prohibited or regulated in many countries (Fujita & Tuttle, 1991). This qualitative study has limitations since the participants had to recall previous experiences related to bat exposures. Among the 30 participating villagers, some individuals still had inappropriate knowledge, attitudes and practices towards bats, exposure activities and bat‐borne diseases; for example, one female participant mentioned that bat guano could be used to cure a skin condition. Our observations were in line with other studies that bats were used to cure asthma, raw bat meat was used to heal wounds, and bat droppings were used to treat pneumonia (Ganeshan & Garden, 2007; Ghosh, 2009; Vats & Thomas, 2015).

In conclusion, our results provide baseline information on the seroprevalence against HCoVs among villagers in Thailand. Lower‐income people are more likely to have coronavirus seropositivity. The results of quantitative and qualitative studies will provide evidence‐based information to assist in risk communication interventions for bat exposure in Thailand. Moreover, serological and CoV surveillance should be routinely conducted in both animal and human populations.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The Ethics Review Committee for Research Involving Human Research Subjects Health Science Group, Chulalongkorn University, and Chiang Rai Provincial Health Office approved the cross‐sectional study and blood collection (Ref No. 034.1/59 and 26/2559, respectively). The Chulalongkorn University Ethical Review Committee also approved the qualitative study (No. 208.1/60). Written informed consent forms were obtained from the study participants prior to the interviews and blood collection. The participants were informed about the objectives and procedures of the study before conducting the quantitative interviews, blood sample collections and qualitative in‐depth interviews.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the current and previous Chief Medical Officers and staff of Provincial Health Offices for their cooperation and assistance during research implementation. We would also like to thank Ms. Siriporn Tiwasing and Ms. Chutima Wacharakul for data collection in the field. Chulalongkorn University supported the Center of Excellence for Emerging and Re‐emerging Infectious Diseases in Animals (CUEIDAs), the Center of Excellence for Clinical Virology and the One Health Research cluster. Chulalongkorn University provided the Second Century Fund (C2F) Postdoctoral Fellowship to the first author (KS). The National Science and Technology Development Agency supported a Research Chair Grant (P‐15‐5004). The Thailand Research Fund provided financial support to the TRF Senior Scholar to the corresponding author (RTA6080012). We are grateful for the financial support from Chulalongkorn University for the research fund under the TSRI fund (CU_FRB640001_01_31_1) and the Second Century Fund (C2F).

Suwannarong K, Janetanakit T, Kanthawee P, et al. Coronavirus seroprevalence among villagers exposed to bats in Thailand. Zoonoses Public Health. 2021;68:464–473. 10.1111/zph.12833

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- Arden, K. E. , Nissen, M. D. , Sloots, T. P. , & Mackay, I. M. (2005). New human coronavirus, HCoV‐NL63, associated with severe lower respiratory tract disease in Australia. Journal of Medical Virology, 75(3), 455–462. 10.1002/jmv.20288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callow, K. A. , Parry, H. F. , Sergeant, M. , & Tyrrell, D. A. (1990). The time course of the immune response to experimental coronavirus infection of man. Epidemiology and Infection, 105(2), 435–446. 10.1017/s0950268800048019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C. M. , Tse, H. , Wong, S. , Woo, P. , Lau, S. , Chen, L. , Zheng, B. J. , Huang, J. D. , & Yuen, K. Y. (2009). Examination of seroprevalence of coronavirus HKU1 infection with S protein‐based ELISA and neutralization assay against viral spike pseudotyped virus. Journal of Clinical Virology, 45(1), 54–60. 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J. F. , Lau, S. K. , To, K. K. , Cheng, V. C. , Woo, P. C. , & Yuen, K. Y. (2015). Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: Another zoonotic betacoronavirus causing SARS‐like disease. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 28(2), 465–522. 10.1128/CMR.00102-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crameri, G. , Durr, P. A. , Barr, J. , Yu, M. , Graham, K. , Williams, O. J. , Kayali, G. , Smith, D. , Peiris, M. , Mackenzie, J. S. , & Wang, L.‐F. (2015). Absence of MERS‐CoV antibodies in feral camels in Australia: Implications for the pathogen's origin and spread. One Health, 1, 76–82. 10.1016/j.onehlt.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dare, R. K. , Fry, A. M. , Chittaganpitch, M. , Sawanpanyalert, P. , Olsen, S. J. , & Erdman, D. D. (2007). Human coronavirus infections in rural Thailand: A comprehensive study using real‐time reverse‐transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 196(9), 1321–1328. 10.1086/521308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dato, V. M. , Campagnolo, E. R. , Long, J. , & Rupprecht, C. E. (2016). A systematic review of human bat rabies virus variant cases: Evaluating unprotected physical contact with claws and teeth in support of accurate risk assessments. PLoS One, 11(7), e0159443. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esper, F. , Weibel, C. , Ferguson, D. , Landry, M. L. , & Kahn, J. S. (2005). Evidence of a novel human coronavirus that is associated with respiratory tract disease in infants and young children. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 191(4), 492–498. 10.1086/428138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, M. S. , & Tuttle, M. D. (1991). Flying foxes (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae): Threatened animals of key ecological and economic importance. Conservation Biology, 5(4), 455–463. 10.1111/j.1523-1739.1991.tb00352.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ganeshan, S. , & Garden, T. B. (2007). Biodiversity and indigenous knowledge system. Current Science, 92(3), 275. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A. K. (2009). Ethnobiology: Therapeutics and Natural Resources. Daya Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Hamre, D. , & Procknow, J. J. (1966). A new virus isolated from the human respiratory tract. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine, 121(1), 190–193. 10.3181/00379727-121-30734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, H. J. , Wen, H. L. , Zhou, C. M. , Chen, F. F. , Luo, L. M. , Liu, J. W. , & Yu, X. J. (2015). Bats as reservoirs of severe emerging infectious diseases. Virus Research, 205, 1–6. 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B. , Ge, X. , Wang, L. F. , & Shi, Z. (2015). Bat origin of human coronaviruses. Virology Journal, 12, 221. 10.1186/s12985-015-0422-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, A. T. , Garcia‐Carreras, B. , Hitchings, M. D. T. , Yang, B. , Katzelnick, L. C. , Rattigan, S. M. , & Cummings, D. A. T. (2020). A systematic review of antibody mediated immunity to coronaviruses: Antibody kinetics, correlates of protection, and association of antibody responses with severity of disease. medRxiv. 10.1101/2020.04.14.20065771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, E. , Bynoe, M. , & Tyrrell, D. (1962). Virus isolations from common colds occurring in a residential school. British Medical Journal, 2(5297), 82. 10.1136/bmj.2.5297.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam, T.‐T.‐Y. , Shum, M.‐H.‐H. , Zhu, H.‐C. , Tong, Y.‐G. , Ni, X.‐B. , Liao, Y.‐S. , & Li, L.‐F. (2020). Identification of 2019‐nCoV related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins in southern China. BioRxiv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, S. K. P. , Woo, P. C. Y. , Li, K. S. M. , Huang, Y. , Tsoi, H.‐W. , Wong, B. H. L. , Wong, S. S. Y. , Leung, S.‐Y. , Chan, K.‐H. , & Yuen, K.‐Y. (2005). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(39), 14040–14045. 10.1073/pnas.0506735102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, S. K. P. , Woo, P. C. Y. , Yip, C. C. Y. , Tse, H. , Tsoi, H.‐W. , Cheng, V. C. C. , Lee, P. , Tang, B. S. F. , Cheung, C. H. Y. , Lee, R. A. , So, L.‐Y. , Lau, Y.‐L. , Chan, K.‐H. , & Yuen, K.‐Y. (2006). Coronavirus HKU1 and other coronavirus infections in Hong Kong. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 44(6), 2063–2071. 10.1128/JCM.02614-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung, G. M. , Lim, W. W. , Ho, L.‐M. , Lam, T.‐H. , Ghani, A. C. , Donnelly, C. A. , Fraser, C. , Riley, S. , Ferguson, N. M. , Anderson, R. M. , & Hedley, A. J. (2006). Seroprevalence of IgG antibodies to SARS‐coronavirus in asymptomatic or subclinical population groups. Epidemiology & Infection, 134(2), 211–221. 10.1017/S0950268805004826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. , Liu, S.‐M. , Yu, X.‐H. , Tang, S.‐L. , & Tang, C.‐K. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): Current status and future perspective. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 55(5), 105951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R. , Zhao, X. , Li, J. , Niu, P. , Yang, B. O. , Wu, H. , Wang, W. , Song, H. , Huang, B. , Zhu, N. A. , Bi, Y. , Ma, X. , Zhan, F. , Wang, L. , Hu, T. , Zhou, H. , Hu, Z. , Zhou, W. , Zhao, L. I. , … Tan, W. (2020). Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet, 395(10224), 565–574. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mildenstein, T. , Tanshi, I. , & Racey, P. A. (2016). Exploitation of bats for bushmeat and medicine. In Voigt C. C. & Kingston T. (Eds.), Bats in the Anthropocene: Conservation of bats in a changing world (pp. 325–375). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, C. , Cryan, P. M. , O'Shea, T. J. , Oko, L. M. , Ndaluka, C. , Calisher, C. H. , Berglund, A. D. , Klavetter, M. L. , Bowen, R. A. , Holmes, K. V. , & Dominguez, S. R. (2011). Alphacoronaviruses in New World bats: Prevalence, persistence, phylogeny, and potential for interaction with humans. PLoS One, 6(5), e19156. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandalj, M. , Treydte, A. C. , & Ziegler, S. (2016). Is wild meat luxury? Quantifying wild meat demand and availability in Hue, Vietnam. Biological Conservation, 194, 105–112. 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.12.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sazzad, H. M. S. , Hossain, M. J. , Gurley, E. S. , Ameen, K. M. H. , Parveen, S. , Islam, M. S. , Faruque, L. I. , Podder, G. , Banu, S. S. , Lo, M. K. , Rollin, P. E. , Rota, P. A. , Daszak, P. , Rahman, M. , & Luby, S. P. (2013). Nipah virus infection outbreak with nosocomial and corpse‐to‐human transmission, Bangladesh. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 19(2), 210–217. 10.3201/eid1902.120971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwannarong, K. , & Chapman, R. S. (2014). Rodent consumption in Khon Kaen Province, Thailand. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health, 45(5), 1209–1220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwannarong, K. , Chapman, R. S. , Lantican, C. , Michaelides, T. , & Zimicki, S. (2015). Hunting, food preparation, and consumption of rodents in Lao PDR. PLoS One, 10(7), e0133150. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwannarong, K. , & Schuler, S. (2016). Bat consumption in Thailand. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology, 6, 29941. 10.3402/iee.v6.29941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vats, R. , & Thomas, S. (2015). A study on use of animals as traditional medicine by Sukuma Tribe of Busega District in North‐western Tanzania. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 11(1), 38. 10.1186/s13002-015-0001-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacharapluesadee, S. , Sintunawa, C. , Kaewpom, T. , Khongnomnan, K. , Olival, K. J. , Epstein, J. H. , Rodpan, A. , Sangsri, P. , Intarut, N. , Chindamporn, A. , Suksawa, K. , & Hemachudha, T. (2013). Group C betacoronavirus in bat guano fertilizer, Thailand. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 19(8), 1349–1351. 10.3201/eid1908.130119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (Producer). (2020, 24 June 2020). WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int

- Zaki, A. M. , van Boheemen, S. , Bestebroer, T. M. , Osterhaus, A. D. , & Fouchier, R. A. (2012). Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(19), 1814–1820. 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. , Chen, X. , Hu, T. , Li, J. , Song, H. , Liu, Y. , Wang, P. , Liu, D. I. , Yang, J. , Holmes, E. C. , Hughes, A. C. , Bi, Y. , & Shi, W. (2020). A novel bat coronavirus closely related to SARS‐CoV‐2 contains natural insertions at the S1/S2 cleavage site of the spike protein. Current Biology, 30(11), 2196–2203.e3. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P. , Yang, X.‐L. , Wang, X.‐G. , Hu, B. , Zhang, L. , Zhang, W. , Si, H.‐R. , Zhu, Y. , Li, B. , Huang, C.‐L. , Chen, H.‐D. , Chen, J. , Luo, Y. , Guo, H. , Jiang, R.‐D. , Liu, M.‐Q. , Chen, Y. , Shen, X.‐R. , Wang, X. I. , … Shi, Z.‐L. (2020). A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature, 579(7798), 270–273. 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.