Abstract

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, Saudi Arabia's domestic public health institutions struggle to control the COVID19 virus's spread within undocumented migrant populations, endangering both local Saudi and migrant populations. As a result, Saudi Arabia implemented a temporary amnesty policy, granting state pardon to undocumented migrants to access to health care services. Using combined qualitative fieldwork data in 2008‐2009 and, more recently in 2020 among irregular Asian and African migrants' communities in Jeddah, I argue that the lack of institutional trust, combined with differential economic opportunities in Saudi and origin countries, significantly impacts undocumented migrants' decision to avoid health amnesty reform. This is particularly critical as it could likely disrupt government attempts at curbing COVID‐19 within migrant communities, thus posing serious health, economic, and security threats to the Saudi state. The study contributes to empirical and theoretical debates because it highlights migrant perception's role towards local institutions in Gulf's domestic migration policymaking.

INTRODUCTION

Governments across Europe are facing calls to urgently put into place measures to protect refugees and migrants – in particular lone children – as the coronavirus epidemic sees volunteer numbers plunge and many vital support services close. (Kelly et al, 2020:1)

The novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) outbreak has disrupted global cross‐border mobility impacting states that structurally depend from migrant worker populations. In Saudi Arabia, COVID‐19 continues to pose multilevel critical threats to Saudis and non‐Saudi populations, recently forcing the Saudi state to implement a health amnesty reform in Saudi healthcare system, a state pardon which specifically allows undocumented migrants to access health‐related assistance linked to COVID‐19 without facing any potential legal arrests, deportations and other civil, criminal or economic sanctions in an attempt to effectively control the spread of COVID‐19 outbreak (Naar, 2020). This health amnesty reform, for example, enables undocumented migrants to access free COVID‐19 testing and treatment in specific local government‐approved hospitals or clinics within the country. 1 Unlike previous amnesty reforms linked to immigration status in Saudi Arabia, the health amnesty reform is very specific to expanding access to healthcare services linked to COVID‐19 pandemic and does not attempt to offer regularization to undocumented migrants in the country. While the Saudi government has not yet published a total number of undocumented migrant beneficiaries, this health amnesty reform has been considered the first major landmark that aimed to not only control COVID‐19 virus but also protect the overall health and welfare of all in the country.

Apart from the health amnesty reform, the Saudi authorities also implemented additional containment measures, including the suspension of the seasonal minor umrah pilgrimage for national and foreign worshippers, the temporal shutting down major land, naval and air communications, and the establishment of a partial curfew. These state‐led initiatives were enforced to suppress the COVID‐19 outbreak, as other similar states like Iran, Western Europe and the United States have continued to struggle to restrict the pandemic. Top Saudi leaders also virtually convened at the G‐20 summit on 26 March 2020, collectively bringing together G‐20 major economies to address the COVID‐19 pandemic, where the Saudi Arabia's King Salman acknowledges Stephens (2020):

We reaffirm our full support for the World Health Organization in coordinating the efforts to counter this pandemic. To complement these efforts, the G20 must assume the responsibility of reinforcing cooperation in financing research and development for therapeutics and a vaccine for COVID‐19 and ensure the availability of the vital medical supplies and equipment. We must also strengthen the global preparedness to counter infectious diseases that may spread in the future. (cited in Al Arabiya, 2020)

Despite these comprehensive state‐led attempts to control irregular migrant communities through health amnesty reform, as well as the critical COVID‐19 virus risks associated with these communities, irregular migrants have remained in Saudi Arabia, often defying state reform policies in order to prolong their stay in the country. This particular dilemma not only raises serious questions about the Saudi state's institutional capacity to uphold its domestic health amnesty reform, but also the differential logic, attitudes and responses of various irregular migrant communities in Saudi Arabia.

This paper explores the effects of Saudi Arabia's recent health amnesty reform on irregular migrant workers, as well as its consequences on migrants and Saudi society. Using combined qualitative fieldwork data in 2008–2009 and, more recently, in 2020 among irregular migrants’ communities—specifically from Asian and African origins—affected by COVID‐19 in Jeddah, I argue that the lack of institutional trust, combined with differential economic opportunities in Saudi and origin countries, significantly impacts undocumented migrants’ decision to avoid health amnesty reform. Refusal of amnesty health provision is a consequent of the historically high‐degree suspicions by undocumented migrants towards Saudi amnesty, as well as the lack of bureaucratic procedures and clarity in Saudi amnesty policy, as previous institutional engagement of migrant workers demonstrates. Without addressing undocumented migrants’ disengagement from this amnesty measure, the degree of public health threats and impact on Saudi Arabia's health system will increase. The presence of COVID‐19‐infected undocumented migrants poses (and has posed) severe economic, health and social costs to the Kingdom and around the world. Any lack of cooperation among involved stakeholders could endanger the entire Saudi population along with the overall migrant populations, as well as add existing institutional pressures to health authorities in the long run.

This paper is divided into three key sections. First, I discuss the demographic profiles of undocumented migrant workers in Saudi Arabia, offering their rationales for remaining in the country, and the ways they have historically navigated through the lack of state healthcare access. Second, I explore how COVID‐19 has differently impacted various undocumented migrant communities, highlighting their logic for refusing amnesty offers by the Saudi state. Third, I unpack how undocumented migrants’ attitudes could further facilitate or undermine Saudi Arabia's legislative response in the context of COVID‐19 crisis in the country. I also analyse the future of COVID‐19 in Saudi Arabia and offer policy recommendations for mitigating a potential public health disaster within undocumented populations in Saudi Arabia.

STATE, AMNESTY REFORM AND UNDOCUMENTED MIGRATION IN TIMES OF COVID‐19 PANDEMIC

Modern nation states have systematically attempted to control the types, scale and magnitude of international migration—specifically undocumented—within their domestic territories depending on the “functional imperatives” of the state Massey et al (2005). Many scholars have documented various state policies (i.e. amnesty, deportation) to curb the flow of undocumented migration in the host country often with mixed outcomes (DE Genova, 2002; Orenius & Zavodny, 2003). In the case of US–Mexico border, Orenius and Zavodny (2003: 437) found amnesty reforms encourage undocumented migration, and thus failing to “change the long‐term patterns of undocumented immigration from Mexico” because it incentivizes undocumented migrants to file and stay in the host country. Linda (2011), however, finds that amnesty reforms reduce border apprehension, thus potentially creating a discouraging effect on undocumented migrants. While these competing results suggest the inconclusive effect of amnesty reforms, the very presence of undocumented migrants also constitutes a direct political threat to their domestic sovereignty, signifying their institutional failure to govern their immigration borders from violators.

Unlike the Western context, empirical studies on state amnesty and undocumented migration in non‐Western states like the Gulf have remained poorly understood. Fargues et.al (2017) broadly define undocumented migrants in the context of the Gulf as: (i) having entered the country without obtaining an official visa (e.g. they were smuggled into Saudi Arabia by land or by sea); (ii) having entered the country legally with Umrah or Hajj visas, but overstayed; (iii) having entered legally with a work permit visa, but left Saudi employers without their consent; and (iii) were born in the city to undocumented parents. While a growing Gulf migration scholarship has identified the complex links between amnesty reforms and undocumented migrants (Shah, 2014; Malit 2020) and their various multiple threats, including sociocultural (Huntington, 1999), security and political threats (Kapiszewski, 1999) in their respective societies and labour markets (Fargues et al, 2017), little studies have yet to explore the relationship between irregular migration, amnesty and public health in crisis context (specifically COVID‐19 pandemic) in the Gulf region, specifically Saudi Arabia that holds the largest proportion (at least 12 million) of migrant workers in the Middle East region.

Most academic work on Gulf migration broadly explores the exploitative experiences of undocumented migrants across sectors linked to the state kafala sponsorship programmes (Jureidini, 2016; Malit and Naufal, 2016) but they often fail to unpack why certain migrants chose to remain undocumented despite the critical presence of amnesty reforms in the host country. These particular “hidden community” of undocumented migrants often live not only in constant fear and danger but also carry serious legal, economic and social precariousness making them more susceptible to labour exploitation due to limited social welfare protection. In particular, undocumented migrant workers’ lack of access to health care thus constitutes not only a serious public health risk to Saudi society especially in times of COVID‐19 pandemic but also a national security threat (Torres & Waldinger, 2015). In other words, more systematic analysis on how Gulf states’ domestic policy reforms—including health amnesty reform—impact undocumented migrant communities are critically needed to understand state‐undocumented migrants’ interaction, as well as its implications both domestically and beyond.

While the lack of constructive empirical and theoretical work on amnesty reforms and undocumented migration in the Gulf creates serious gaps in the literature, existing studies suggest critical economic and institutional factors that drive low compliance to amnesty reforms. In Kuwait, Shah (2014) suggests that the differential opportunities extended to undocumented migrants in the host and origin countries often shape their decision to avail (or not) the amnesty programme. Other critical factors, such as host country social networks, knowledge of the Arabic language and economic benefits working in the informal sector, often impact the decision of undocumented migrants to exploit the amnesty options. In addition, Shah (2014) further contends.

The lived experiences of many interviewees described in this volume suggest that several migrants may not see their irregular status as being disastrous. Many, in fact, are willing to perpetuate this situation, despite their awareness about possible arrest, jail term, and deportation… To survive in an irregular status becomes normality for many. They learn to negotiate the formal and informal spaces and systems they encounter. Many have specific goals they want to achieve during their Gulf stay, whatever the cost. (p. 8)

For many undocumented migrants, staying in the host country is imperative for their own and their families’ survival. These calculations shape therefore their choices to use or ignore amnesty, a decision also shaped, as this paper will show, by their own understandings of state amnesty and the perceived risks involved.

In the UAE, Malit (2020) found that because of the bureaucratic procedures and costly nature of amnesty applications, many irregular migrants chose not to avail the amnesty options, thereby contributing to state failure to eradicate undocumented migration. He further found that migrant workers often use “strategic illegality” approach in the labour market where they prefer to remain in irregular legal status in order to avoid administrative or immigration costs. While amnesty is a powerful incentive for undocumented migrants to regularize their status, the propensity to earn higher in the informal Gulf market outweighs the benefits of amnesty. Jureidini (2016) discusses the high costs of recruitment paid by migrant workers, which often discourages certain migrants (i.e. Bangladeshis) to abscond from their employer in an attempt to earn income in the informal economy. Thus, the differential opportunities and costs of availing amnesty options not only shape undocumented migrants’ microeconomic behaviours but also signify the various determinants and consequences of availing amnesty options for undocumented migrants in the Gulf countries.

With the emergence of COVID‐19 pandemic, the Gulf states have further employed amnesty reforms in recent months to control the spread of COVID‐19 virus. In fact, undocumented migrants living across the Gulf, in particular, have become prime policy targets for states, given the large scale of undocumented migrant populations floating within the Gulf labour market. To a large extent, COVID‐19 pandemic has made Gulf society particularly vulnerable to public health crises, thereby influencing the Saudi state to institute healthcare policy reforms in favour of undocumented workers (Nugali, 2020). The recent Saudi health amnesty reform not only attempts to control the effects of COVID‐19 pandemic on undocumented migrants, but also necessitates stronger local cooperation between undocumented migrants and Saudi health authorities to improve institutional transparency and coordination. As a migrant from Sudan who lived through the MERS outbreak in Jeddah notes,

Many undocumented migrants expressed fears to report even various types of medical illnesses …. There was no royal decree during the MERS outbreak similar to the present one [COVID 19]. Access to medical care was also not available. (Al Karantina District, South Jeddah, April 19, 2020)

As an unprecedented measure, the Saudi amnesty programme has also not been implemented in various past outbreaks like the MERS in 2012, but became an important domestic policy reform in the Gulf that enabled undocumented migrants to equally access public health institutions in order to stop COVID‐19 virus outbreak 2 Bell (2018).

By focusing on the case of Saudi Arabia, this paper attempts to unpack the complex interaction between the state and undocumented migrants, as well as the logic, coping strategies and consequences of choices related to amnesty options in the host country. Through the use of multiple case study communities among selected African and Asian migrant populations, this paper highlights the differential reasoning and attitudes towards Saudi health amnesty reform, as well as its implications for Saudi state policymaking and engagement with hidden migrant communities in the long run. This paper does not only offer in‐depth qualitative evidence but also highlights complex and multilevel perspectives during COVID‐19 pandemic crises that could potentially explain the determinants and consequences of amnesty reforms in Saudi Arabia and of the broader Gulf region.

METHODOLOGY AND DATA SNAPSHOT

Conducting field research linked to the undocumented migrant population remains a critical challenge for Gulf‐based and international researchers De‐Bel Air (2014). In Saudi Arabia, it becomes particularly challenging due to issues pertaining to trust, security, ethics and a weak culture of data collection. In order to conduct this empirical study, I have mainly relied on empirical data collected at different time frames. The first set of data was gathered during fieldworks carried out in 2008 and 2009 (Al Sharif, 2015). The data, which covers sixteen different undocumented communities of migrants living and working illegally in Saudi Arabia, were collected from the city of Jeddah. I also conducted interviews with gatekeepers from fifteen various communities, covering two fieldwork periods in December 2019 and January–February 2020 before the COVID‐19 outbreaks in Saudi Arabia. 3 To further enrich the time series analysis of my qualitative data, I facilitated follow‐up interviews with select few of the gatekeepers from 12 April to 19 April 2020. Under government curfews to prevent the spread of COVID‐19, these interviews were conducted via telephone calls as well as various social media messaging systems (WhatsApp, Skype) in order to reach this particular hidden population. Although this field research has been specifically focused on Jeddah, the collected fieldwork data could have a potential universal value in reflecting the views, perceptions and attitudes of undocumented migrants towards state health amnesty offers. This particular follow ‐p interviews with migrants mainly attempted to examine factors that determine their decision to avail health amnesty reforms in Saudi Arabia. This is particularly relevant in all of Saudi Arabia, as well as other Gulf countries, due to their similar legislative laws on labour and employment and immigration.

In all the above fieldwork cases, interviewing hidden or undocumented populations (females, males, nationality differences, age groups) significantly carried critical risks and challenges to both insiders/outsiders in the field of migration field Atkinson and Flint (2001). This particular difficulty exists not only within the Saudi labour market but also in the other Gulf labour markets, where undocumented migrants seemed inaccessible (Fargues et al, 2017; Alsharif, 2017). Thus, I relied on gatekeepers from each migrant community to offset prevailing fieldwork restrictions. Various themes, including undocumented migrants’ “medical needs” and “attitudes towards amnesty policy initiatives” by the Saudi government, were also examined. A demographic snapshot of these fifteen different communities of undocumented migrants’ communities is critical to provide rich comparisons, specifically related to their perceptions, views and logical reasoning towards Saudi Arabia's amnesty policies. Table 1 below provides a brief qualitative description of the most critical variables about the fifteen communities under investigation, including their nationality, age, gender, marital status and religion.

Table 1.

A Snapshot of the Undocumented Migrants’ Demographic Background, 2008‐2009.

| Nationality | NMC | % | Gender |

Average Age |

Marital Status | ANCH | Religion | ALED* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | MA | S | D | W | M | C | ||||||

| Yemeni | 29 | 12 | 14 | 15 | 28 | 13 | 15 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 29 | 0 | 5.6 |

| Filipino | 26 | 11 | 16 | 10 | 32 | 10 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 24 | 11 |

| Indonesian | 30 | 13 | 18 | 12 | 29 | 13 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 2.4 | 30 | 0 | 6 |

| India | 28 | 12 | 8 | 20 | 26 | 4 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 28 | 0 | 10 |

| Pakistani | 24 | 10 | 8 | 16 | 34 | 18 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 24 | 0 | 5 |

| Bangladeshi | 36 | 15 | 12 | 24 | 37 | 16 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 36 | 0 | 9 |

| African | 61 | 27 | 18 | 43 | 36 | 27 | 23 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 58 | 3 | 3.6 |

| Total | 234 | 100 | 94 | 140 | x̅ = 32 | 101 | 121 | 10 | 2 | x̅ = 4 | 207 | 27 | x̅ = 7 |

Abbreviations: %, per cent; ANCH, average number of children; C, Christian; D, divorced; F, female; M, male; M, Muslim; MA, married; NMC, number of migrants in each community; S, single; W, widow; x̅, average mean.

ALED=average level of education of interviewees calculated by using US high school grade level system that uses 12‐grade levels. Grade 0 (zero) stands for no formal education, Grade 1 stands for the first year in school, and Grade 12 stands for the final year in high school

Source: Author's fieldwork data (2015)

This study analyses undocumented migrants from the Yemen, the Philippines, Indonesia, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, and the African community. These specific subject communities of undocumented migrants constitute a very complicated case, as they pose real social, economic and security consequences for the Saudi authorities due to the diversity of their countries of origin, languages and cultures AlSharif (2019). These specific factors have certainly posed serious constraints to Saudi Arabia in terms of upholding amnesty policies in recent decades. Table 1 indicates that there were 234 females and males from fifteen undocumented migrant communities who lived and worked in Jeddah (Alsharif, 2017). The number of females was 94, representing 40 per cent of the population under study, while 60 per cent were male. The total average mean, x̅, was 32 years old for both genders. The majority in this sample (88%) were Muslims, while the remaining (12%) were Christians who were mostly from the Philippines. In relation to their marital status, the majority of interviewees were married (52%), although (43%) identified as single. The remaining 5 per cent were either divorced or widowed. The average mean, x̅, for the number of children for all interviewees were four children. In terms of the level of education, the subjects varied from having no formal education to high school education (Grade 12 in the US system.) The average mean, x̅, of education level for all, was grade 7 with the Filipino migrants scoring grade 11, seconded by the Indian migrants, grade 10. The above data qualitatively offer the readers a demographic overview of undocumented migrants’ social, educational backgrounds in the city of Jeddah.

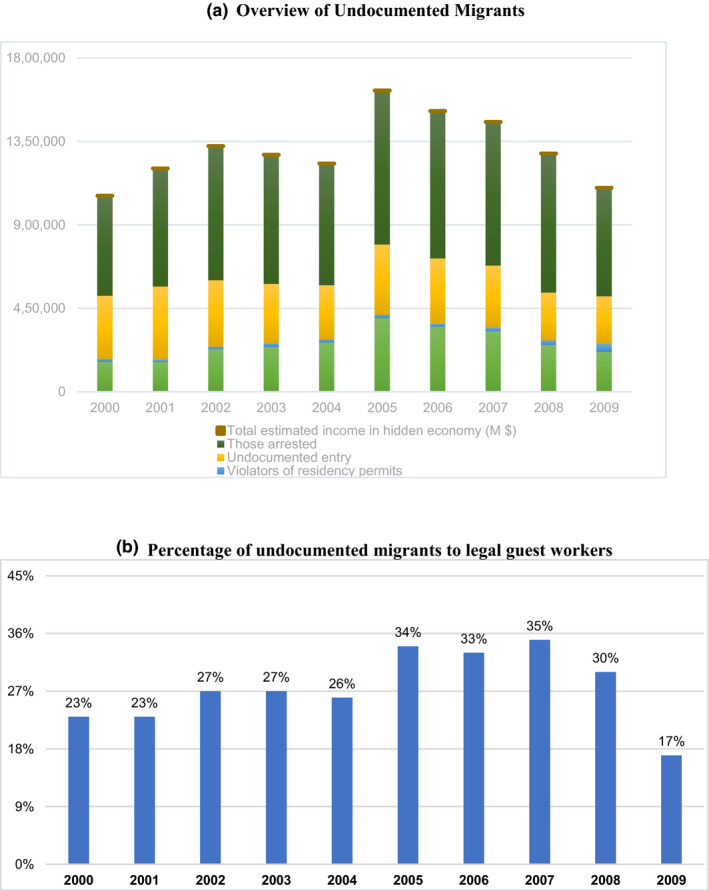

UNDOCUMENTED MIGRANTS IN SAUDI ARABIA

In Saudi Arabia, undocumented migrants constitute a large share of the total population. Due to their diversities, the undocumented migrants’ community in Saudi Arabia offers an excellent entry point to isolate complex security issues encountered by most Saudi authorities in various national interior or labour ministries. Analysing the prevailing attitudes and perceptions of undocumented migrants towards Saudi Amnesty generates an exceptional opportunity to evaluate the multilevel efficiencies or constraints of Saudi policies, which various Saudi institutions have aggressively implemented in recent decades. al‐Mutayrī (2012) highlights essential aggregated data on undocumented migrants from various governmental agencies. Figure 1 shows the various trends and statistic of undocumented migrants in the Kingdom from 2000–2009, ranging from 17 per cent to 35 per cent of total migrant populations. These include those who come on Hajj and Umrah visas and have deliberately overstayed as undocumented migrants as well as those who exploit Saudi's weak southern borders through illegal cross‐border entries into the country.

Figure 1.

(A) Overview of Undocumented Migrants. (B) Percentage of undocumented migrants to legal guest workers. Source: Both Figure 1a,b are adopted from unpublished statistical data from the General Bureau of Passport and Naturalisation cited in al‐Mutayrī (2012).

In addition, many legal expatriates, however, who come to the country for work on a contract basis with a kafeel (sponsor) often break their contracts for a variety of reasons, including inadequate work conditions, long working hours and lack of salary payments, or to pursue better wage options in the private sector. Many end up joining the labour market as freelancer. Although the exact numbers of contract breakers are not known, these groups constitute a substantial population, especially given the high percentage of expatriates in Saudi Arabia, as Table 1 shows. In contrast to expatriate populations in the United States and United Kingdom, estimated at only 1.37 per cent and 14 per cent, respectively, Saudi Arabia has around 37 per cent which amounts to over 12 million people. Contract violators thus increase the already existing pool of undocumented migrant labour, complicating government efforts to lower the number of undocumented persons.

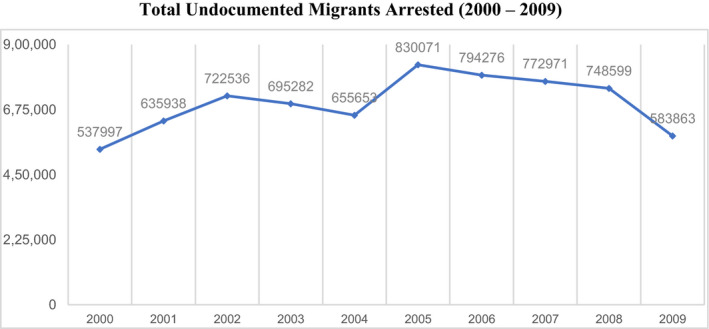

In response, Saudi Arabia, like other Gulf States, has often securitized the “hidden” presence of undocumented migrant workers within their national territories. This emphasis on security has often entailed various labour and human rights violations, a by‐product also of the restrictive nature of the kafala sponsorship system. More specifically, Saudi Arabia has issued in recent decades multiple amnesties to curtail the number of undocumented migrants in the country. In addition, Saudi Arabia (like other Gulf States) has imposed suspensions, fines, jail sentences and, above all, deported undocumented migrants to their countries of origin (Cabanding, 2017). From 2000 to 2009, as Table 2 shows, Saudi authorities arrested a total of 6,977,186 undocumented migrants, averaging at 697,719 per year. Recently in September 2019, the Saudi Gazette reported that local authorities had arrested 3.87 million undocumented migrants, illegally living and working in the country, over a 22‐month amnesty period. According to the report, of the total 962,234 deported migrants, 62 per cent violated the country's labour and employment law. 4 Meanwhile, the number of expatriates arrested for violating residency regulations was 3,024,270, while another 252,128 migrants were arrested for having breached border security. The state report further notes that an additional 1,555 Saudi nationals were detained for sheltering the undocumented, although they were eventually released after serving sentences or paying state‐determined sanctions. 45 per cent of undocumented migrants constituted Yemenis, 52 per cent Ethiopians and the remaining 3 per cent of various nationalities (Saudi Gazette, 2014; Figure 2).

Table 2.

Percentage of Expatriates to National in KSA, UK and the USA.

| Country | Total Number of Nationals | Total Number of Expatriates | Total | Approx. % of Expatriates to the National Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saudi Arabia | 20,768,627 | 12,645,033 | 33,413,660 | 37% |

| UK | 57,135,550 | 9.300,000 | 66,435,550 | 14% |

| USA | 322,700,000 |

3,000000 to 6, 000,000 (an average of 4.500,000) |

327.200,000 | 1.37% |

Sources: The General Authority for Statistics (GAStat)

Figure 2.

Total Undocumented Migrants Arrested (2000 – 2009).

Furthermore, the government has restricted undocumented migrants to healthcare access, essentially blocking all opportunity to avail service from any state medical facilities in the country. The policy initiative was also designed to limit healthcare access to barring residents without appropriate documents. As one Saudi newspaper highlights: “no medical treatment will be provided to any individual without adequate papers.” For example, Saudi citizens must show their national identification card (Betakah aḥwāl), while expatriates have to present document of legal residency (Iqamah). Field fieldwork data I collected from my previous study fully confirm the limited access of undocumented migrants to healthcare services in Saudi Arabia (Alsharif, 2017). Without appropriate health care, undocumented migrants often risk worsening of their physical and mental ailments, often exacerbated by their continual fear of being discovered and deported (Human Rights Watch, 2015).

Although Western states like the United States and United Kingdom have traditionally passed amnesty policies or regularization to grant legal residency and citizenship pathways, Saudi Arabia has not made such provisions available to undocumented migrants. The differential approaches can be explained by the following: (1) the large migrant population size, totalling 33 per cent of the entire population (see Table 1 above); (2) the presence of holy cities Makkah and Madinah, where over 30 million pilgrims are expected to arrive for Hajj and Umrah by 2030. Because of these high demographic imbalances, Saudi Arabia faces significant constraints in providing amnesty options to migrant populations (Kéchichian & Alsharif, 2021). In this regard, governing undocumented migrants remains difficult for Saudi Arabia, often putting massive institutional pressures on the country's infrastructures and resources.

INDIVIDUAL MIGRANT COMMUNITY RESPONSES AND COPING STRATEGIES

This section examines the concerns, attitudes and perceptions of undocumented migrants towards healthcare Saudi Arabia, and how they negotiate health concerns vis‐à‐vis the absence of formal healthcare access. Crucially, undocumented migrants have found ways to obtain forms of health‐ care through various means. Health issues also remained less a priority in their lives, although the COVID‐19 crisis has changed this.

The African community

In the case of African respondents, all subjects indicated their lack of access to public hospitals in Jeddah in cases of medical emergency and, in some cases, private hospitals or clinics, if they can afford it. However, due to government's restriction, many have had to rely on their personal networking to obtain medical care and consult with the nearest pharmacist or see one of the local attars (traditional medical/herbal practitioners) for medical advice. As one interviewee from Eritrea noted:

We can go to private hospitals even if we use other special hospitals where there are Egyptian doctors. They understand and do not charge us a lot. We use other Eritreans’ documented papers to go to private hospitals.

Another interviewee from Somalia confirmed this:

We can go to private hospitals even if we do not use other people’s papers, especially hospitals where there are Egyptian doctors. They understand and do not charge us a lot for medical examination.

Also, due to their exclusion from the health service, undocumented immigrants have resorted to “borrowing” ID cards to access health care. Nineteen (31.1%) noted that they had used IDs that were not their Iqama (Residency documents) to gain access to medical care in Saudi public/private hospitals. Forty‐two interviewees (68.95%) indicated that they have never done this because it was deemed too risky.

Yemenis

Like the African community, Yemeni interviewees (100%) noted no access to public hospitals in Jeddah, and some access to private hospitals or clinics if they have funding. Others, however, as highlighted in the Al‐Hindawiya district, rely on small clinic in the early morning to provide them with basic services for minor illnesses and injuries. In 2010, the cost of these services was noted to be around eight dollars which often trigger many Yemenis to seek a consultation with the nearest pharmacist or see one of the local Attar (traditional medical/herbal practitioners). In case of emergencies, private hospitals were accessible because they did not ask for identification cards compared to public hospitals. Out of the 29 interviewees, only four females admitted that they had used IDs (iqama or residency documents) that belong to others to gain access to medical care in Saudi public/private hospitals. The rest, 25 interviewees, indicated that they had never done this because it was perceived to be dangerous.

Filipinos and Indonesians

Unlike other various migrant communities, both Filipinos and Indonesians seem to have some advantage in accessing both private and public health systems. The large concentration of Filipino medical professionals in Saudi Arabia, in particular, combined with their tight knit close community, provides an advantage in seeking medical treatment irrespective of their legal status. As a 28‐years‐old female interviewee from the Philippines said:

I have many female and male Filipino friends who work in private hospitals or clinics, which help me receive medical treatment without asking me to provide a valid iqama…sometimes free of charge.

The vast majority of females and males from both the Filipino and Indonesian communities work in private and public hospitals and in private clinics, as medical staff, including nurses, technicians who supervise the maintenance of medical equipment, drivers and other related medical jobs. Both communities have relied on the social network of their documented friends in hospitals and private clinics to gain access to free and safe medical treatment. Eighteen (69.2%) of the Filipino interviewees noted that in case of a medical emergency, they had access to private hospitals and/or medical clinics in Jeddah. Eight (30.8%) said they did not have access, and they would seek the advice of a pharmacist. As far as medical needs for those interviewed from the Indonesian community was concerned, seven (23.3) indicated they had friends in the private hospitals who could help them receive medical care. The remaining 23 Indonesians sought help either from the small medical clinic in the south Jeddah al‐Hindawiya district, or see a pharmacist. The vast majority in both communities, who could not access medical care for some reason, noted that they would consult with the nearest pharmacist. With regard to the use of IDs, out of the 26 interviewees from the Filipino community, only eight (30.7%), five females and three males, admitted that they had used IDs that belongs to others to gain access to medical care in Saudi public/private hospitals. The other 18 (69.2%) indicated that they had never done this because it was risky. For the Indonesian community, all 30 interviewees noted that they had never used IDs that were not theirs to gain access to medical care.

South Asian Migrants (including Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis)

The undocumented from the above communities enjoyed less problematic access to health facilities than the African migrant populations due to the strength of their community social networks. Like Filipino and Indonesian migrants, many Indians and Pakistani irregular migrants either lived close to health facilities or have community networks who work in private hospitals as general physicians or dentists. These social networks enable them to effectively access public health institutions and resources in Saudi Arabia. However, the vast majority of males from these three communities worked as drivers, freelance construction workers, electricians, or toiled in barbershops and grocery stores, or similar jobs. They also utilized their relationships with their fellow citizens to leverage their medical access to various health institutions if they could. Only five Indian interviewees (18%) noted that in the case of a medical emergency, they had access to medical care through using their documented friend's legal IDs. Twenty (71%) indicated they had a selected private clinic in the city that often treated them for minor conditions, for a fee. Only three (9%) interviewees noted they had no access, and they usually tried to find out a pharmacist for advice. For the Pakistani migrants, fifteen (62%) indicated they could access small private clinics for a fee. The rest, nine (38%), found a solution by using Attar (non‐traditional medicine) or went to a pharmacy for medical advice. For the Bangladeshi migrants, eighteen (50%) noted they used friends’ legal papers to receive medical care. In this regard, their case was unique because many of them could pass as members of the Burmese community who had resided in KSA with legal documents since the 1960 s, when they arrived in the country as refugees from Burma.

UNDOCUMENTED MIGRANTS’ RESPONSES TOWARDS AMNESTY IN SAUDI ARABIA

With the war against COVID‐19 raging, Saudi authorities have quickly provided healthcare amnesty to undocumented migrant. Even if the royal amnesty is clear in allowing all the undocumented access to medical facilities without being subject to any punishment, however, interviews suggest that most of them would not avail the opportunity due to fears of being arrested and deported. Saudi policy on amnesty for undocumented migrants remains ambiguous, as recent arrests of Ethiopian migrants demonstrate.

Security authorities in Riyadh arrested 53 Ethiopians in contravention of the residency and work system, after circulating a video clip showing their taking caves and mountain cracks in the Mahdia neighbourhood in Riyadh as hideouts for their hiding. In the details, the police spokesman for the Riyadh region, Lt. Col. Shaker bin Suleiman Al‐Tuwaijri, stated that it is a reference to the video clip circulating and showing a group of violators of residence and work regulations, by taking the rugged caves and cracks in the Mahdia neighbourhood, west of the capital, Riyadh, as hiding places. And the arrest of (53) violators of the residency system, all of whom are Ethiopian. Al‐Tuwaijri added: All legal measures were taken against them (cited in Saudi News, 2020).

This above case pertaining to the Ethiopian migrants’ recent experience clearly shows the lack of a coherent implementation of the newly revised health policies for undocumented migrants. Fieldwork data also suggest that undocumented migrants often deliberately resist in reporting any labour, civil or immigration problems to the local authorities due to potential deportation procedures by the Saudi police apparatus. In this regard, if the national implementation of any new state‐led health intervention against COVID‐19 is not fully backed by a solid, coherent state involvement on the ground, mistrust towards authorities by undocumented migrants will only continue. The issue of trust and local cooperation between undocumented migrants and the state is not new. Responses from communities regarding amnesty use collected in 2008/2009 also reflect this.

As Table 3 demonstrates, most of the undocumented migrants in the city of Jeddah (applicable to the whole country) tended to reject using amnesty policies initiated by the Saudi government, despite a majority having indicated that their undocumented status was a reason for concern. For instance, when asked about whether they would take advantage of the most recent amnesty initiative, which allowed undocumented migrants to safely exit from Saudi Arabia to his or her home country of origin with no penalty, 82 per cent (191 out of 234 respondents) rejected the possibility of using an amnesty. In contrast, only 18 per cent (43 interviewees) noted they would use potentially use if offered by the government. Of the total interviewees, 186 or (79%) noted that they were satisfied with working and living in Jeddah, while the other 48 respondents (21%) acknowledged their dissatisfaction. The respondents’ answer to the second question “Does living in Jeddah with no documents bother/concern you?” resulted in 165 (or 71%) indicated their concerns, while the other 29 per cent had no particular issues living without documents in the country.

Table 3.

Attitude Towards Living in Jeddah and the Use of Amnesty (2008–2009).

| Nationality | In general, are you satisfied with working and living in Jeddah? | Does living in Jeddah with no documents bother/concern you? | If an amnesty initiative by the Saudi authority takes place now or in the future, will you to use it? | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | % | No | % | Yes | % | No | % | Yes | % | No | % | |

| Yemeni | 26 | 90 | 3 | 10 | 10 | 34 | 19 | 66 | 3 | 10 | 26 | 90 |

| Filipino | 15 | 58 | 11 | 42 | 26 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 88 | 3 | 12 |

| Indonesian | 25 | 83 | 5 | 17 | 4 | 13 | 26 | 87 | 8 | 27 | 22 | 73 |

| Indian | 22 | 79 | 6 | 21 | 20 | 71 | 8 | 29 | 3 | 11 | 25 | 89 |

| Pakistani | 20 | 83 | 4 | 17 | 19 | 79 | 5 | 21 | 2 | 8 | 22 | 92 |

| Bangladeshi | 30 | 83 | 6 | 17 | 25 | 69 | 11 | 31 | 4 | 11 | 32 | 89 |

| African | 48 | 79 | 13 | 21 | 61 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 100 |

| Total | 186 | 79 | 48 | 21 | 165 | 71 | 69 | 29 | 43 | 18 | 191 | 82 |

Source: Author's fieldwork data (2015).

Furthermore, in the follow‐interviews conducted in January 2020 with migrant‐represented community leaders, all of them—with the exception of the Yemenis—had a negative perception of these amnesty policies (Personal interview in Jeddah, 2020). Incidentally, the vast majority of the Yemeni migrants in the interviews conducted during 2008–2009, also matched the Yemeni gatekeeper's opinion (Alsharif, 2017). Other nationalities like Pakistanis came next with 92 per cent and the Indian and Bangladeshis had at 89 per cent each. In addition, all the members of the African communities, 61 or 100 per cent acknowledged their rejection to use amnesty even if offered by the government. As one interviewee from Burkina Faso noted,

I do not know… I am happy about being undocumented and not using the amnesty pardon because I am frightened, that they [the Saudi authorities] will arrest me or after taking my fingerprints will deport me, and I will not be able to come back. (Alsharif, 2017: 135)

The only community of undocumented migrants, who were willing to use amnesty, if offered, were the Filipinos, with 88 per cent answering “yes” to amnesty provisions. Nonetheless, the data here demonstrate the vast majority of respondents affirming their rejection of amnesty. This potentially limit of success of Saudi Arabia in effectively implementing an amnesty initiative is a consequence of migrants’ perceived fears and risks linked to the government initiative.

The hesitance of undocumented migrants towards amnesty carries heavy implications for the Saudi government's amnesty initiative against COVID‐19 today. Gatekeepers from the various undocumented communities have expressed, in follow‐up interviews, little change of migrant positions towards the recent amnesty initiative (Table 4). Despite their differential contexts and circumstances, undocumented migrant workers continue to disengage with the Saudi state. While amnesty provisions may encourage some undocumented migrant workers to use the amnesty services (like the Filipino migrants), the majority have stated that they do not intend to use the amnesty health provision due to deep institutional mistrust towards Saudi authorities. This highlights the limits of recent Saudi amnesty in addressing healthcare concerns of migrant communities in Kingdom. Table 4 below reflects the general position of many undocumented migrant workers in Saudi Arabia.

Table 4.

Gatekeepers’ Responses on the three questions raised here (an update from 2020).

| Nationality | In general, do you think your community is satisfied with their working and living in Jeddah? | In general, does living in Jeddah with no documents concern your community? | Do you think, overall, if an amnesty initiative by the Saudi authority takes place now or in the future, will the majority of your community use it? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yemeni | Yes, the majority are satisfied | No, the majority are not concerned | No, the majority will not use it, circular migration is easy. |

| Filipino | Yes, to a certain extent, the majority are satisfied. | Yes, the great majority are concerned. | Yes, the vast majority will use it. |

| Indonesian | Yes, I think they are satisfied. | Yes, the majority are concerned. | No, the majority will not use it |

| Indian | Yes, I think they are satisfied | yes, it concerns them a bit. | No, the majority will not use it |

| Pakistani | Yes, I think they are satisfied | yes, it concerns them | No, the majority will not use it |

| Bangladeshi | Yes, I think they are satisfied | yes, it concerns them | No, the majority will not use it |

| African: nine different communities | Yes, I think they are satisfied | yes, it concerns them | No, the vast majority will not use it |

Source: Author's fieldwork data (2020).

The following section contains a brief discussion and updated responses of various gatekeepers, summarizing the undocumented migrants’ present and past health issues and their impacts on their legislative perceptions towards Saudi Arabia. During the follow‐up interviews, gatekeepers were asked the following questions:

In what way (s) did COVID‐19 affect members of your community?

Are there members of your community or others who were infected by the virus but did not seek treatment?

Are the undocumented aware of the availability of access for medical treatment, and do you anyone who used it and was not subject to arrest?

Do you recall the virus health hazard of MERS‐CoV of 2012? How did it affect your community?

What follows is an overview of responses by the majority of the interviewees (gatekeepers) regarding COVID‐19 and undocumented communities in Jeddah.

I will give you some of the information I have. According to my knowledge, the southern districts of Jeddah, where the majority of undocumented live… For example, al‐Hindawiya, al‐Sabeel, al‐Karantina… Living in this area are large communities… Chadian, Somali, Nigerians, some Sudanese, and a large Yemenis community. A significant percentage are illiterates. The curfew does not control them. Inside these districts, they continue their everyday lives of selling and buying. This carelessness is the most dangerous behaviour under the present circumstances caused by the virus. With regards to awareness of the recent government decree to allow the undocumented access to health‐care, and the number of infected people that we know… For the first, the vast majority are aware of the decree but are afraid to do it, and for the second question, it is complicated to determine the number for many reasons. Most are so scared, and they trust no one. They are afraid to seek help. If one has the symptoms, he thinks if he seeks help, he and his family will be subject to jail and deportation. They measure this based on past experiences with authorities.

If you ask me how much money I have, almost nothing but we are managing. I lived here, and my children were born in this country…they do not know much about our native country. We have to stand with the government where we have lived safely for many years. We lived and were raised in this country, even our children who have never seen their country of origin. Many like me are willing to volunteer to help not only our community but others as well. If the government opens volunteering to help the ill, many will join. As for myself, I would rather die assisting others in the field than dying in my bed at home with my family. I suggest the following: the government should be encouraged to recruit individuals from each undocumented community to spread more awareness on the dangers of spreading the virus in their respective communities on the risks of violating government curfews.

In this view, if Saudi Arabia wanted to achieve public health access for all, reliable and transparent procedures and regulations are required to handle the critical link between undocumented migrants and the healthcare system. Amnesty remains insufficient if not implemented with clear procedures and backed by a capillary communication strategy that is effectively communicated to this hidden population. In this view, effective public communication of the new procedures should be delivered clearly to the target migrant population, namely the undocumented migrants’ communities. In addition, to fully engage and govern undocumented migrant communities, Riyadh ought to proactively build community trust with all stakeholders to effectively exercise the capacity of amnesty policy to protect the health and welfare of all migrant workers. While issuing amnesty may only be part of the solution, building long‐term trust and communication with migrant communities remains vital in achieving effective national migration governance in the future. In this view, this paper proposes the following recommendations as crucial in limiting the spread of COVID‐19 outbreak:

Increase trust between these communities and health authorities by engaging in a campaign to communicate the importance of adhering to health rules as suggested by the government in this particular moment of crisis.

Assure communities that their members would not face any punishment when approaching health authorities through appointing legal migrants from these communities as middlemen.

Implement a system that allowed undocumented migrants to call emergency services without the threat of retaliation.

Develop more robust and long‐term cooperation with foreign embassies to facilitate undocumented migrants’ identification and presence in the country.

Use alternative approaches, including the behavioural economic tactic (nudging), which may increase trust and awareness and hence improve the likelihood that many hesitant undocumented could be persuaded to use it, compared to the traditional methods of no fine, no jail incentives.

Facilitate welfare assistance (i.e. temporary housing, food, shelter) by organizing a vast public shelter facility where the vast majority of undocumented migrants (including those who lost their jobs) with suspected COVID‐19 virus live.

Saudi authorities can offer a specific advantage in migrant's area of concern. For example, they could link the healthcare services use to an unconditional renewal of migrant's work permit for a limited period. For example, three months.

CONCLUSION

As the largest destination for migrant workers and travellers in the Gulf and across the Middle East region, Saudi Arabia has had for centuries received millions of pilgrimages and migrants Through this, the Kingdom has accumulated experience and knowledge in handling various pandemic outbreaks, including the MERS virus. The COVID‐19 virus, however, appears to be “unbeatable” in the short term. This uncertain situation has not only posed critical economic issues for the Saudi government, but also influenced senior Saudi officials to shift its priorities from state security to human concern, resulting in the passage of the healthcare provision for undocumented migrant workers in the Kingdom. Specifically, the Saudi government has decided to liberalize its domestic healthcare services to the undocumented migrants in order to prevent public health threats posed to the Saudi and migrant populations.

While this humanitarian step has become an important pillar to address the spread of COVID‐19, ethnographic data, both historical and present, suggest critical limitations to the potential effectiveness of healthcare amnesty, including community fears of deportation. Furthermore, all data from different communities pointed to the same conclusion: Not everyone enjoyed legal access to healthcare facilities. This situation could prove to be a dangerous one in the current emergency caused by the uncontrolled spreading of the coronavirus. Under the circumstances, it may be far better to suggest a drastic, urgent change of the current amnesty provision, to guarantee the maximum degree of prevention and to control the smaller number of contagions before increased numbers prevented manageable responses. More importantly, the “trust” factor between the Saudi state and undocumented migrant populations has historically recorded to be low. This is critical to the current or future implementation of any Saudi amnesty policy because non‐engagement by such hidden populations will only exacerbate the growing effects of COVID‐19 on Saudi society.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/imig.12838.

Appendix 1.

This appendix contains brief details of each gatekeeper interviewed in the period between 29 December 2019 and 8 February 2020. It includes nationality, age, gender, marital status, occupation, date of interview and comments, if any.

| Gatekeeper | Nationality | Age | Gender | Marital status | Occupation | Date | Place of interview | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sudan | 60 | Male | married | painter | 12‐ 29‐2019 | Al‐Karantina | Saturday |

| 2 | Ethiopia | 33 | Female | Single | Housemaid | 1‐9‐2020 | Al‐Hindawiya | Thursday evening |

| 3 | Chad | 78 | Male | Married | Retired | 1‐9‐2020 | Al‐Hindawiya | Thursday evening |

| 4 | Somali | 24 | male | single | Carpenter | 1‐10‐2020 | Al‐Bawadi | Friday |

| 5 | Eretria | 32 | Male | Single | Driver | 1‐9‐2020 | Al‐Bawadi | Friday |

| 6 | Nigeria | 23 | Male | Single | Grocery store | 1‐10‐2020 | Al‐Karantina | Friday |

| 7 | Ghana | 36 | Female | married | housemaid | 1‐11‐ 2020 | Al‐Karantina | Saturday |

| 8 | Burkina‐ Faso | 47 | Male | Married | Collects & sell scraps | 1‐11‐ 2020 | Al‐Hindawiya | Saturday |

| 9 | Cameroon | 55 | Male | Single | Washes cars | 1‐23‐ 2020 | Ash‐Sharafiya | Thursday |

| 10 | Yemen | 19 | Male | Single | Sells near‐expired goods | 1‐24‐ 2020 | Al‐Hindawiya | Friday |

| 11 | Indonesia | 44 | Female | Single | Housemaid | 1‐24‐ 2020 | Al‐Zahra | Friday |

| 12 | Philippines | 23 | Male | Single | Computer technician | 2‐7‐2020 | Al‐Jamaa | Friday |

| 13 | Pakistani | 37 | Male | Married | Driver | 2‐7‐2020 | Al‐Zahra | Friday |

| 14 | Indian | 50 | Male | Married | tailor | 2‐7‐2020 | Al‐Faysaliya | Friday |

| 15 | Bangladesh | 35 | Female | Single | Sales | 2‐8‐2020 | Al‐Bawadi | Saturday |

ENDNOTES

During the full lockdown in Saudi Arabia, irregular migrants, who chose not to avail the health amnesty reforms, are often not punished, depending on the degree and type of cases committed in the country. However, the Saudi authorities have maintained continuous surveillance since March 2020 in an attempt to carefully examine potential pathways to limiting the risks brought by COVID‐19 pandemic in the country.

On 30 March 2021, the Saudi Minister of Health declared that the country's monarch, King Salman bin Abdulaziz, has directed that free treatment of Coronavirus (COVID‐19) be provided to citizens, residents and residency violators throughout the Kingdom….[and] that the authorities have never hesitated to apply all precautionary measures to prevent the coronavirus, adding that here is coordination between all concerned parties. The Saudi Minister of Health emphasized that everyone inside the Kingdom must apply health measures to preserve society's safety. The Decree covers all health care needed without time limitation or preconditions. https://www.skynewsarabia.com/middle‐east/1332534‐%D8%B9%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AC‐%D9%83%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%88%D9%86%D8%A7‐%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%B9%D9%88%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%A9‐%D9%8A%D8%B4%D9%85%D9%84‐%D9%85%D8%AE%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%81%D9%8A‐%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%95%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%A9

Due to the exceptional circumstances of conducting field data collection and survey during COVID‐19, I had to utilize gatekeepers by partnering with certain migrants who are not only public community leaders but also hold significant access and insights about their respective communities. They have usually lived at least ten years (10) in their respective communities and are a part of their diaspora organizations and networks dealing with cases and issues pertaining to the lives of their migrant communities, including irregular migrants.

Saudi Arabia does not regularly publish public data on irregular migrants in the country. Given the data limitations, the author attempts to offer some public estimates using existing available state data to highlight the scale and magnitude of irregular migration in the country. The 2019 September estimate is the closest data available, and given the recent Saudi market closures and unemployment, the author estimates that the population of irregular migrants remains high in the country.

REFERENCES

- al‐Mutayrī, H. (2012) Qiyās Hajm al‐Iqtisād al‐Khafi wa Atharuhu ʿalā al‐Mutaghayyirāt al‐Iqitisād Al‐Kuli ma ʿa Dirāsaht tatbiqiyya ʿalā al‐Mamlakah al‐ʿArabiyyah al‐Suʿūdiyyah khilāl al‐Fatrah: 1390‐1430 AH (1970‐2009) AD, unpublished PhD Thesis. Saudi Arabia: Jamiat Um Alquraa. [Google Scholar]

- Alsharif, F. (2017) Calculated Risks, Agonies, and Hopes: A Comparative Case Study of the Undocumented Yemeni and Filipino Migrant Communities in Jeddah. In: Fargues, P. & Shah, N.M. (Eds.), Skilful Survivals: Irregular Migration to the Gulf. [Google Scholar]

- Alsharif, F. (2019) “City of Dreams, Disappointment, and Optimism: The Case of Nine Communities of Undocumented African Migrants in the City of Jeddah” Dirasat. Riyadh, KSA: King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R. & Flint, J. (2001) ‘Accessing Hidden and Hard‐to‐Reach Populations: Snowball Research Strategies’, Issue 33. Surrey: University of Surrey. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J. (2018) Sep 6, 2018, Viral victory: How Saudi Arabia won the war against MERS. Available from https://www.arabnews.com/node/1367491/saudi‐arabia

- Cabanding, I. (2017) Saudi grants another amnesty extension for illegal expats. Available from: https://news.abs‐cbn.com/overseas/09/22/17/saudi‐grants‐another‐amnesty‐extension‐for‐illegal‐expats [Accessed 17 April 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- De Bel‐Air, F. (2014) Demography, Migration and Labour Market in Saudi Arabia. [Online]. Available from http://gulfmigration.eu

- De Genova, N. (2002) Migrant Illegality” and Deportability in Everyday Life. Annual Review of Anthropology, 31, 419–447. [Google Scholar]

- Fargues, P. , Shah, N.M. (Eds). (2017) Skilful Survivals: Irregular Migration to the Gulf. [Google Scholar]

- Jureidini, R. (2016) Ways Forward in the Recruitment of Low‐Skilled Migrant Workers in the Asia‐Arab Migration Corridor. ILO White Paper. Available from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/‐‐‐arabstates/‐‐‐ro‐beirut/documents/publication/wcms_519913.pdf

- Kéchichian, J. & Alsharif, A. (2021), Sacred Duty versus Realistic Strategies: Saudi Policies Towards Migrants and Refugees. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, A. , Grant, H. & Tondo, L. (2020) NGOs raise alarm as coronavirus strips support from EU refugees. Available from https://www.theguardian.com/global‐development/2020/mar/18/ngos‐raise‐alarm‐as‐coronavirus‐strips‐support‐from‐eu‐refugees

- Linder, J. (2011) The Amnesty Effect: Evidence from the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act. Available from https://www.american.edu/spa/publicpurpose/upload/2011‐public‐purpose‐amnesty‐effect.pdf

- Malit, F.T. & Alawad, M. (2019) Strategic Illegality under the GCC Amnesty Reform: The Case of the United Arab Emirates. Unpublished Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Malit, Jr. F. (2020) Amnesty Reforms in the Gulf: Issues and Policy Options. Unpublished Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Malit, Jr. F. & Naufal, G. (2016) Asymmetric Information under the Kafala Sponsorship System: Impacts on Foreign Domestic Workers’ Income and Employment Status in the GCC Countries. International Migration, 54(5), 76–90. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D.S. , Arango, J. , Hugo, G. , Kouaouci, A. , Pellegrino, A. & Taylor, J.E. (2005) Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–466. [Google Scholar]

- Naar, S. (2020). Timeline Saudi Arabia’s proactive measures to combat the COVID19, Al Arabiya. Available from https://english.alarabiya.net/en/features/2020/03/28/Timeline‐Saudi‐Arabia‐s‐proactive‐measures‐to‐combat‐the‐COVID‐19‐coronavirus.html [Google Scholar]

- News, A. . Arab News . (2020). King Salman orders free coronavirus treatment in Saudi Arabia, including residency violators. Arab News, March 30, 2020. Available from https://www.arabnews.com/node/1650026/saudi‐arabia

- Nugali, N. (2020) Saudi Arabia ‘acted, not reacted’ to COVID‐19 pandemic. Arab News, Available from https://arab.news/rz9e7 [Google Scholar]

- Orrenius, P. & Zavodny, M. (2003) “Do Amnesty Programs Reduce Undocumented Immigration” Evidence from IRCA. Demography, 40(3), 437–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saudi News . (2020) 53 Ethiopians arrested in violation of the residence and work system in the ‘Mahdiyat Al‐Riyahd'—Saudi Arabia. Available from https://m.saudi24.news/2020/04/53‐ethiopians‐arrested‐in‐violation‐of‐the‐residence‐and‐work‐system‐in‐the‐mahdiyat‐al‐riyadh‐saudi‐arabia‐news.html

- Saudi Gazette . 3.87m illegal foreigners netted, 962, 234 deported in 22 months. Available from https://saudigazette.com.sa/article/577935

- Shah, N. (2014) Recent amnesty programmes for irregular migrants in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia: some successes and failures. Technical Reform, Migration Policy Centre, GLMM Explanatory Note 9/2014. Available from https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/34577

- Stephens, M. (Friday, March 27 2020), The coronavirus crisis is the time for the G20 to really show what it can do. Available from https://english.alarabiya.net/en/views/news/middle‐east/2020/03/27/Now‐is‐the‐time‐for‐the‐G20‐to‐really‐show‐what‐it‐can‐do.html

- Torres, J. & Waldinger, R. (2015) Civic Stratification and the Exclusion of Undocumented Immigrants from Cross‐border Health Care. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 56(4), 438–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]