Abstract

Background

In response to the COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia, restrictions to elective surgeries were implemented nationwide.

Aims

To investigate the response to these restrictions in elective gynaecological and In vitro fertilisation (IVF) procedures during the first wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Materials and Methods

We analysed the Medicare Item Reports for the number of elective gynaecological (labioplasty, vulvoplasty; prolapse and continence; operative hysteroscopy; hysterectomy; fertility) and IVF procedures claimed in Australia between January–June 2020 and compared these to January–June 2019.

Results

The number of included gynaecological and IVF procedures performed in January–June 2020 decreased by −13.71% and −12.56%, respectively, compared to January–June 2019. The greatest reductions were in May 2020 (gynaecology −43.71%; IVF −51.63% compared to May 2019), while April 2020 reported decreases of −37.69% and −31.42% in gynaecological and IVF procedures, respectively. In April 2020, 1963 IVF cycle initiations (−45.20% compared to April 2019), 2453 oocyte retrievals (−26.99%) and 3136 embryo transfers (−22.95%) were billed. The procedures with greatest paired monthly decrease were prolapse and continence surgeries in April (676 procedures; −51.85%) and May 2020 (704 procedures; −60.05%), and oocyte retrievals in May 2020 (1637 procedures; −56.70%).

Conclusions

While we observed a decrease in procedural volumes, elective gynaecological and IVF procedures continued in considerable numbers during the restricted timeframes. In the event of future overwhelming biological threat, careful consideration must be given to more effective measures of limiting access for non‐emergency procedures to conserve essential resources and reduce risk to both the public and healthcare staff.

Keywords: COVID‐19, elective surgery, gynaecology, in vitro fertilisation, Medicare Benefits Schedule

Introduction

In response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic in Australia, restrictions to elective surgeries were implemented nationwide to mitigate patient and staff risk, 1 ensure adequate hospital capacity, and preserve personal protective equipment. 2 From 25 March, 2020, all elective surgeries and procedures were suspended in public and private hospitals nationally, with the exception of Category 1 (clinically indicated within 30 days) and some exceptional Category 2 procedures (clinically indicated within 90 days). 2 , 3 This decision was supported by The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG), who recommended restricting surgeries to Category 1 procedures only. This included: assessment and treatment of suspected or proven gynaecological malignancy; miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy and termination of pregnancy; acute haemorrhage and acute‐on‐chronic pelvic pain failing medical management; acute pelvic pain; 1 and continued access to current contraceptive methods. 4 Following containment of spread of COVID‐19, elective surgeries gradually resumed from 27 April, 2020, commencing with the re‐introduction of Category 2 and some important Category 3 procedures (clinically indicated within 365 days), including in vitro fertilisation (IVF) procedures. 3 , 5 The timeline for return to full capacity from 15 May, 2020 was at the discretion of individual jurisdictions. 6

While national guidelines exist, 3 elective surgery clinical urgency categorisation is governed by individual jurisdictions. Furthermore, during the pandemic, a directive from National Cabinet deemed categorisation to be at the discretion of the healthcare provider. 2 As such, the level of urgency as determined by the treating practitioner may not necessarily have been in line with national, jurisdiction or RANZCOG guidelines, resulting in the possibility of elective medical procedures proceeding against recommendations.

Our study aims to compare the number of selected elective gynaecological and IVF procedures claimed through the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) in Australia between January and June 2019, and January and June 2020. Comparisons may determine the response to recommendations and the type and volume of procedures considered ‘clinically urgent’ during the COVID‐19 pandemic billed via Australia’s national medical payment system.

Materials and Methods

This study was exempt from ethics approval as per the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number HC200554). We searched the relevant jurisdiction governmental department websites for policies and guidelines pertaining to elective surgery clinical urgency categorisation. In addition, we utilised the Google search engine for national elective surgery clinical urgency categorisation guidelines using the terms ‘Australia’ AND ‘elective surgery’ AND ‘categorisation’. We also searched for restrictions to elective surgery during the COVID‐19 pandemic using the search terms ‘COVID‐19’ AND ‘Australia’ AND ‘elective surgery’. We repeated this search, adding ‘RANZCOG’ as an additional search term.

We reviewed the MBS item reference lists 7 between January and June 2019, and January and June 2020, and extracted all gynaecological and IVF MBS item numbers. Medicare Item Reports 8 were analysed for the number of gynaecological and IVF procedures claimed in Australia during the same timeframe by item, state and month. We selected groups of item numbers for study based on usual categorisation codes of urgency, and excluded codes where it is not possible to separate data due to acuity of presentation or for malignancy. Data were extracted on miscarriage and termination, and outpatient contraception procedures as comparators that were not included when reporting change in surgical volumes by time period. MBS item numbers were grouped as summarised in Table 1. Numbers of procedures are presented as absolute values without statistical comparison by month or year.

Table 1.

Included elective gynaecological and IVF procedures, MBS item numbers and clinical urgency category

| Procedure | MBS item numbers | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Gynaecology | ||

| Vulvoplasty, labioplasty | 35533, 35534 | Not specified |

| Prolapse and continence | 35568, 35570, 35571, 35572, 35573, 35577, 35578, 35581, 35582, 35585, 35595, 35597, 35599, 35602, 35605, 35684 |

Stress incontinence and vaginal repair surgery: Category 3 in ACT, Tasmania, Victoria and WA; not specified in NSW Other procedures: not specified |

| Operative hysteroscopy | 35616, 35622, 35623, 35633, 35634, 35635, 35636 |

NSW: Category 2 Other jurisdictions: Category 3 |

| Benign hysterectomy | 35653, 35657, 35661, 35673, 35750, 35753, 35754, 35756 | Category 3 |

| Non‐IVF‐related fertility procedures | 35694, 35697, 35700, 35703, 35706, 35709, 35710 |

Tubal dye studies: Category 3 Other procedures: not specified |

| IVF | ||

| Initiation of IVF cycle | 13200, 13201 | Not specified |

| Oocyte retrieval | 13212 | Not specified |

| Embryo transfer | 13215 | Not specified |

| Comparison procedures | ||

| Miscarriage and termination | 35640, 35643 |

WA: Category 1 Other jurisdictions: not specified |

| Outpatient contraception | 35502, 35503 |

35502: Category 2 35503: Category 3 |

ACT, Australian Capital Territory; IVF, in vitro fertilisation; MBS, Medicare Benefits Schedule; NSW, New South Wales; WA, Western Australia.

Clinical urgency categorisation

The National Elective Surgery Urgency Categorisation Guideline lists common gynaecological procedures and their recommended category. 3 Category 1 procedures are those clinically indicated within 30 days, Category 2 procedures within 90 days and Category 3 procedures within 365 days, with patient factors and the clinical situation taken into account. Western Australia, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory provide obligatory policies for clinical urgency categorisation. 9 , 10 , 11 New South Wales (NSW) and Victoria offer guidelines only. 12 , 13 In South Australia (SA), categorisation is at the discretion of the healthcare provider, 14 while no documentation pertaining to clinical urgency categorisation could be located for the Northern Territory (NT). Directives for all jurisdictions apply to the public health system and are not mandated in the private sector. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 The category of included gynaecological and IVF procedures in this study is summarised in Table 1. Categorisation excludes SA and the NT and where the jurisdiction is not stated, the category applies to all.

Results

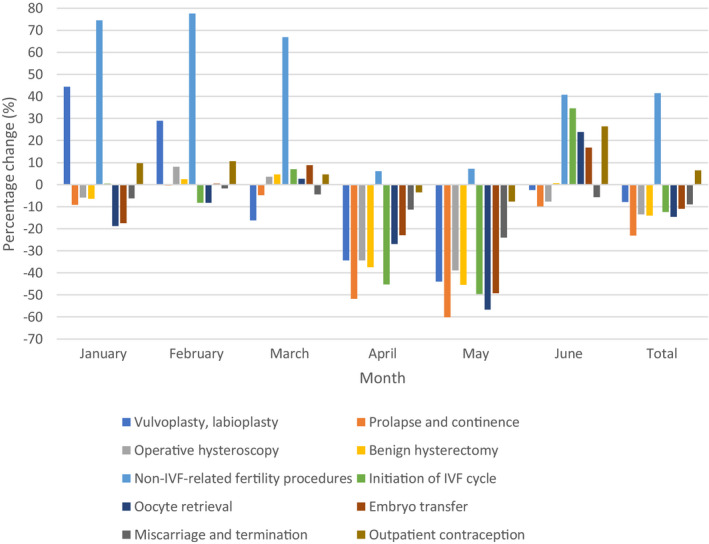

A total of 41 gynaecological, four IVF and four comparison MBS item numbers, corresponding to 63 340, 116 754 and 132 343 claims, respectively, processed between January and June 2019, and January and June 2020, were included in the analyses. Table 2 details claims processed in the two six‐month periods by type of procedure, while Figure 1 illustrates the percentage difference in the number of procedures processed per month of 2020 compared to the same month of 2019.

Table 2.

Number of selected billable elective gynaecological and IVF procedures claimed in Australia in January–June 2019 and January–June 2020

| Procedure | Year | Number of procedures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | February | March | April | May | June | Total | ||

| Gynaecology | ||||||||

| Vulvoplasty, labioplasty | 2019 | 27 | 31 | 43 | 35 | 41 | 40 | 217 |

| 2020 | 39 | 40 | 36 | 23 | 23 | 39 | 200 | |

| Prolapse and continence | 2019 | 1415 | 1586 | 1674 | 1404 | 1762 | 1498 | 9339 |

| 2020 | 1286 | 1578 | 1595 | 676 | 704 | 1351 | 7190 | |

| Operative hysteroscopy | 2019 | 2294 | 2407 | 2723 | 2593 | 3035 | 2667 | 15 719 |

| 2020 | 2161 | 2600 | 2818 | 1704 | 1857 | 2464 | 13 604 | |

| Benign hysterectomy | 2019 | 1164 | 1166 | 1200 | 1146 | 1327 | 1200 | 7203 |

| 2020 | 1090 | 1194 | 1255 | 717 | 725 | 1208 | 6189 | |

| Non‐IVF‐related fertility procedures | 2019 | 188 | 223 | 217 | 242 | 317 | 336 | 1523 |

| 2020 | 328 | 396 | 362 | 257 | 340 | 473 | 2156 | |

| IVF | ||||||||

| Initiation of IVF cycle | 2019 | 1668 | 3917 | 3563 | 3582 | 3995 | 3385 | 20 110 |

| 2020 | 1676 | 3592 | 3814 | 1963 | 2014 | 4555 | 17 614 | |

| Oocyte retrieval | 2019 | 1845 | 3508 | 3274 | 3360 | 3781 | 3359 | 19 127 |

| 2020 | 1498 | 3219 | 3363 | 2453 | 1637 | 4159 | 16 329 | |

| Embryo transfer | 2019 | 2275 | 3988 | 4033 | 4070 | 4600 | 4086 | 23 052 |

| 2020 | 1879 | 4007 | 4390 | 3136 | 2335 | 4775 | 20 522 | |

| Comparison procedures | ||||||||

| Miscarriage and termination | 2019 | 4869 | 4549 | 4650 | 4021 | 4836 | 4148 | 27 073 |

| 2020 | 4562 | 4472 | 4443 | 3564 | 3673 | 3913 | 24 627 | |

| Outpatient contraception | 2019 | 5380 | 6737 | 6981 | 5996 | 7503 | 6476 | 39 073 |

| 2020 | 5907 | 7452 | 7306 | 5791 | 6921 | 8193 | 41 570 | |

IVF, in vitro fertilisation.

Figure 1.

Percentage change in selected billable elective gynaecological and IVF procedures claimed in January–June 2020 compared to January–June 2019. The number of procedures claimed during these periods were extracted from the Medicare Item Reports. Medicare Benefits Schedule item numbers were then grouped by type of procedure. The difference in the number of procedures claimed per month in 2019 and 2020 was expressed as a percentage of the number of procedures claimed in the same month of 2019. IVF, in vitro fertilisation.

The total decrease in included procedures performed in the first half of 2020 compared to the same period of 2019 was −13.71% and −12.56% for gynaecological and IVF item numbers, respectively. Prolapse and continence surgeries, oocyte retrievals and benign hysterectomy had the greatest decrease between the two periods (−23.01%, −14.63% and −14.08%, respectively), while non‐IVF‐related fertility procedures increased (+41.56%).

When comparing paired monthly data, May 2020 reported the greatest downturn compared to 2019 (−43.71% and −51.63% for gynaecological and IVF procedures, respectively, range −60.05% to +7.26% for individual procedure types), while April 2020 reported decreases of −37.69% and −31.42% in gynaecological and IVF procedures, respectively (range −51.85% to +6.20%). IVF procedural volumes in June 2020 exceeded those of 2019 by +24.55%, while gynaecological surgical volumes fell by −3.59% (range −9.81% to +40.77%). The procedures with the greatest paired monthly decrease between 2019 and 2020 were prolapse and continence surgeries claimed in April and May (−51.85% and −60.05%, respectively), and oocyte retrievals claimed in May (−56.70%).

Miscarriage and termination, and outpatient contraception procedures rose by +0.08% during the first six months of 2020 compared to the same period of 2019. Changes of −6.61%, −14.14% and +13.95% in April, May and June 2020, respectively, were documented compared to the corresponding months of 2019.

NSW and Victoria, the states that experienced the highest number of COVID‐19 cases and longest lockdown periods, reported decreases of −8.99% (NSW) and −19.29% (Victoria) in gynaecological, and −12.70% (NSW) and −13.70% (Victoria) in IVF procedures during the two six‐month periods.

Discussion

Suspension of all elective surgeries excepting Category 1 and exceptional Category 2 procedures was announced by National Cabinet from 25 March, 2020. 2 From 27 April, 2020, Category 2 gynaecological surgeries and IVF procedures could be reintroduced, with no Category 3 gynaecological surgeries permitted and volume limits recommended on all surgical procedures. 5 Using April 2020 as the key indicator of the response to elective surgery restrictions, the number of Category 2 and Category 3 procedures should be close to zero. This was not the case, with all procedure types continuing in substantial numbers, albeit reduced compared to the same time interval in the preceding year, with the exception of non‐IVF‐related fertility procedures that increased during this time. This increase is likely due to a shift in outpatient treatments such as contrast ultrasound procedures used for fertility. 15 , 16 There were no specific COVID‐19 restriction guidelines published in Australia for ultrasound practices, with the Australian Society of Ultrasound Medicine recommending that infertility ultrasounds be deferred during this time. 17 , 18

The timing of claims submission could be a factor in these figures, since Medicare Item Reports are reported by process date, rather than procedure date. 8 This may affect allocation of procedures by month; however, the effect is likely to be similar for all months. Given the rebound increase in June 2020 claims with the change in regulations, this effect is likely to be minimal. Following the incremental recommendations to elective procedures announced from the end of April 2020, the response to restrictions is more difficult to analyse, with states and territories implementing varied regulatory arrangements. 6

Classification of procedures such as vulvoplasty, labioplasty, fertility procedures, or surgery for prolapse or continence as Category 1 during the month of April 2020 is difficult to justify. Even if there are truly exceptional circumstances, such cases would not account for the substantial number of procedures claimed in this month. The fact that these continued at the height of the COVID‐19 pandemic when the depth of the crisis and risk posed to patients and staff were unknown suggests that decision making by patients, clinicians and healthcare providers did not take full consideration of the public healthcare issues.

Both National Cabinet and the Fertility Society of Australia recommended cessation of IVF cycle initiation and embryo transfers for the month of April 2020. 2 , 5 , 19 Women already considered ‘in‐cycle’ appropriately were allowed to continue with treatment. 19 , 20 However, a substantial number of cycle initiations and embryo transfers continued to be performed in April 2020, suggesting other contributors to the performance of these procedures during the restrictions.

Hysterectomy and operative hysteroscopy procedures billed during the restricted time interval are higher than anticipated. We excluded MBS item numbers for radical hysterectomy for malignancy and would expect only a small number of those included to be for other cancers. The commonest indications for hysterectomy are leiomyomata (32.4%), abnormal uterine bleeding (16.6%) and prolapse (12.2%), 21 all of which could be considered elective. While unique situations such as severe anaemia or pre‐malignant pathology might occur, these factors would not account for the 717 hysterectomies billed in April 2020 (a −37.43% drop from 2019 for the same time interval).

By comparison and although unaffected by elective surgery restrictions, we observed a decrease in miscarriage and termination procedures, possibly reflecting decreased pregnancy rates and/or desire for pregnancy, or greater numbers of non‐surgical management. Similarly, a small decrease in outpatient contraception procedures was reported in April and May 2020 compared to the same months of 2019, possibly due to decreased face‐to‐face outpatient appointments during this period. Outpatient contraception claims increased substantially in June 2020, which may possibly be due to decreased desire for pregnancy due to the uncertainty of the pandemic.

It is possible that the cessation of elective surgery may have resulted in delayed gynaecological cancer diagnosis in some patients, since occult cancer was diagnosed in 2.23% of hysterectomies and 0.21% of myomectomies in one retrospective series. 22 However, the true effect is unknown at this time, with gynaecological cancer incidences for this period unavailable. These data may be impacted by other factors such as delayed presentation during the pandemic.

This study only includes procedures performed in the private sector, since data pertaining to public procedures are not provided by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare until the year following the surgical separation. Additionally, the Medicare Item Reports do not contain information regarding billing multiple MBS items for a single surgery and it is possible that non‐urgent procedures presented in this study were performed in conjunction with Category 1 or 2 procedures. However, these are likely to account for only a small proportion of total cases and do not explain the continuance of non‐urgent elective procedures in substantial numbers during this time.

The response to elective surgery restrictions in gynaecology and IVF within Australia is considerably poorer than reported internationally during the pandemic. Elective orthopaedic services in Hong Kong were reduced by 73.5% and approached the directed 80% decrease. 23 Similarly, Germany reported a 75% decrease in both elective and emergency hernia procedures in April 2020 compared to February to June 2019, 24 despite elective surgeries only being postponed between 12 March and 19 April. 25 The poorer Australian response in gynaecology cannot be attributed to the lower number of infectious cases in this country since in the initial stages, the transmissibility and mortality associated with the virus were as unknown here as they were internationally, and our data are a timely reminder as Europe is in the midst of its second wave of infections.

There is no doubt that urgent elective procedures required interventions to be performed, even at the height of the COVID‐19 pandemic. However, the volume of procedures classed as ‘urgent’ and performed during this time is concerning. The maintenance of business to keep staff employed and demand pressures from patients are factors to be considered; however, this must be balanced against the necessity to protect the wider community at a time when the full extent of the COVID‐19 pandemic was unknown. These data suggest there was suboptimal compliance with national recommendations regarding restricting practice. While this lack of self‐regulation may apply to a minority of doctors, careful consideration must be given to more effective measures in future situations to ensure that the health of patients, staff and the public are not compromised.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. COVID‐19: Category 1 (Australia) and Urgent (New Zealand) Gynaecological Conditions and Surgical Risks, 2020. [Accessed 8 July 2020.] Available from URL: https://ranzcog.edu.au/news/category‐1‐gynaecological‐conditions

- 2. Morrison S. Elective Surgery, 2020. [Accessed 8 July 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.pm.gov.au/media/elective‐surgery

- 3. Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council . National Elective Surgery Urgency Categorisation, 2015. [Accessed 8 July 2020.] Available from URL: https://ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG‐MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical%20‐%20Gynaecology/National‐Elective‐Surgery‐Categorisation‐5.pdf?ext=.pdf

- 4. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . COVID‐19: Access to Reproductive Health Services, 2020. [Accessed 22 September 2020.] Available from URL: https://ranzcog.edu.au/news/covid‐19‐access‐to‐reproductive‐health‐services

- 5. Morrison S. Update on Coronavirus Measures, 2020. [Accessed 8 August 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.pm.gov.au/media/update‐coronavirus‐measures‐210420

- 6. Australian Health Protection Principal Committee . Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) Statement on Restoration of Elective Surgery and Hospital Activity, 2020. [Accessed 9 July 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.health.gov.au/news/australian‐health‐protection‐principal‐committee‐ahppc‐statement‐on‐restoration‐of‐elective‐surgery‐and‐hospital‐activity

- 7. Australian Government Department of Health . MBS Online, 2020. [Accessed 8 July 2020.] Available from URL: http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/Home

- 8. Services Australia . Medicare Item Reports, 2020. [Accessed 15 August 2020.] Available from URL: http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.jsp

- 9. Department of Health . Elective Surgery Access and Waiting List Management Policy, 2019. [Accessed 10 July 2020.] Available from URL: https://ww2.health.wa.gov.au/‐/media/Files/Corporate/Policy‐Frameworks/Clinical‐Services‐Planning‐and‐Programs/Policy/Elective‐Surgery‐Access‐and‐Waiting‐List‐Management‐Policy/Elective‐Surgery‐Access‐Waiting‐List‐Management‐Policy.pdf

- 10. Tasmanian Department of Health . Wait List Access Policy Surgical and Non‐surgical Waitlist Handbook, 2020. [Accessed 10 July 2020.] http://www.dhhs.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/60175/Wait_List_Access_Policy_Surgical_and_Non‐Surgical_Waitlist_Handbook.pdf

- 11. Australian Capital Territory Health . Waiting Time and Elective Surgery Access Policy, 2016. [Accessed 10 July 2020.] Available from URL: https://cms.health.act.gov.au/media/5485

- 12. New South Wales Ministry of Health . Advice for Referring and Treating Doctors ‐ Waiting Time and Elective Surgery Policy, 2012. [Accessed 10 July 2020]. Available from URL: https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/IB2012_004.pdf

- 13. Department of Health and Human Services . Appendix 2: Victorian Recommended Guide on the Assignment of Clinical Urgency Categories, 2015. [Accessed 10 July 2020.] Available from URL: https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/publications/policiesandguidelines/appendix‐2‐guide‐on‐assignment‐of‐clinical‐urgency‐categories

- 14. South Australia Health . Elective Surgery Policy Framework and Associated Procedural Guidelines, 2011. [Accessed 9 August 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/07cd7280482dfb079467f47675638bd8/Elective+Surgery+Policy+Framework_Amended_+29032018.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE‐07cd7280482dfb079467f47675638bd8‐n5hSC4W

- 15. Wang R, van Welie N, van Rijswijk J et al. Effectiveness on fertility outcome of tubal flushing with different contrast media: systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019; 54(2): 172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dreyer K, van Rijswijk J, Mijatovic V et al. Oil‐based or water‐based contrast for hysterosalpingography in infertile women. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(21): 2043–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Australasian Society For Ultrasound In Medicine. COVID‐19 resources, 2020. [Accessed 21 September 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.asum.com.au/covid‐19‐resources/

- 18. International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology . ISUOG consensus statement on rationalization of gynecological ultrasound services in context of SARS‐CoV‐2. 2020. [Accessed 21 September 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.isuog.org/uploads/assets/fc11c841‐c56d‐4e3e‐a29ce3975555d652/ISUOG‐Consensus‐Statement‐on‐rationalization‐of‐gynecological‐ultrasound‐services‐in‐context‐of‐SARS‐CoV‐2.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19. The Fertility Society of Australia . Updated statement of the COVID‐19 FSA Response Committee (24 March. 2020), 2020. [Accessed 2 November 2020.] https://www.fertilitysociety.com.au/wp‐content/uploads/20200324‐COVID‐19‐Statement‐FSA‐Response‐Committee.pdf

- 20. Department of Health and Human Services . Coronavirus disease (COVID‐19): guidance for assisted reproductive treatments, including in‐vitro fertilisation, 2020.

- 21. Merrill RM. Hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 1997 through 2005. Med Sci Monit 2008; 14(1): CR24–CR31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Desai VB, Wright JD, Schwartz PE et al. Occult gynecologic cancer in women undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy for benign indications. Obstet Gynecol 2018; 131(4): 642–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wong JSH, Cheung KMC. Impact of COVID‐19 on orthopaedic and trauma service: an epidemiological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2020; 102(14): e80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kockerling F, Kockerling D, Schug‐Pass C. Elective hernia surgery cancellation due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Hernia 2020; 24(5): 1143–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Graf R, Cools A, Schmithausen D. Consequences of the COVID‐19 Pandemic on the Treatment of Patients in German hospitals – A First Impression, 2020. [Accessed 16 September 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.3mhisinsideangle.com/blog‐post/consequences‐of‐the‐covid‐19‐pandemic‐on‐the‐treatment‐of‐patients‐in‐german‐hospitals‐a‐first‐impression/