Abstract

Background

The COVID‐19 pandemic is a massive global health crisis with damaging consequences to mental health and social relationships. Exploring factors that may heighten or buffer the risk of mental health problems in this context is thus critical. Whilst compassion may be a protective factor, in contrast fears of compassion increase vulnerability to psychosocial distress and may amplify the impact of the pandemic on mental health. This study explores the magnifying effects of fears of compassion on the impact of perceived threat of COVID‐19 on depression, anxiety and stress, and social safeness.

Methods

Adult participants from the general population (N = 4057) were recruited across 21 countries worldwide, and completed self‐report measures of perceived threat of COVID‐19, fears of compassion (for self, from others, for others), depression, anxiety, stress and social safeness.

Results

Perceived threat of COVID‐19 predicted increased depression, anxiety and stress. The three flows of fears of compassion predicted higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress and lower social safeness. All fears of compassion moderated (heightened) the impact of perceived threat of COVID‐19 on psychological distress. Only fears of compassion from others moderated the effects of likelihood of contracting COVID‐19 on social safeness. These effects were consistent across all countries.

Conclusions

Fears of compassion have a universal magnifying effect on the damaging impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health and social safeness. Compassion focused interventions and communications could be implemented to reduce resistances to compassion and promote mental wellbeing during and following the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID‐19 pandemic, fears of compassion, mental health, moderator effect, multinational study, social safeness

Key Practitioner Message.

Fears of offering compassion to oneself and others, and of receiving compassion from others, have been found to significantly predict poorer mental health and social safeness.

These fears of compassion were found in this study to also predict poorer mental health and social safeness during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Importantly, fears of compassion (for self, for others and from others) magnified the damaging impact of perceived threat of COVID‐19 on mental health, but only fears of receiving compassion from others heightened this impact on social safeness.

It is recommended that individual, group and community‐based compassion‐focused interventions, such as compassion focused therapy and compassionate mind training, be used to reduce fears of compassion and therefore help protect against mental health difficulties during and following the pandemic.

1. INTRODUCTION

The current coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic presents modern societies a challenge of historic proportions. The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared early that the pandemic is a public health emergency of international concern (World Health Organization (WHO), 2020), and a year later infection rates remain very high across many countries, and the number of deaths has now far surpassed two million worldwide (Worldometer, 2021). The COVID‐19 pandemic not only affects physical health, but also has multifaceted severe consequences to mental health and social well‐being (e.g., Palgi et al., 2020; Rajkuman, 2020) and can be viewed as a global stressor because of the threat to health, damaging economic consequences and disruption of daily routines.

Throughout history, the sudden emergence and rapid spread of novel infectious diseases have caused much fear and consternation, as well as strict interventions by authorities, such as social distancing, isolation and lockdown, which then caused further fear and a terrifying sense of other people as threats (Van Damme & Van Lerberghe, 2000). Similarly, in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic, countries throughout the world have implemented several strategies to limit the spread of the virus and reduce pressures on healthcare services. Some of these strategies include community level restrictions with varying degrees of social distancing measures, such as self‐isolation or lockdown procedures, which cause significant disruption to people's daily lives. Although government regulations are necessary to address the main challenges posed by the current pandemic, there is a lack of consideration towards the impact such measures have on mental health and psychosocial well‐being (Serafini et al., 2020). These restrictions and the characteristics of the virus itself (e.g., being highly contagious, invisible in nature), have resulted in common social behaviours (e.g., shaking hands and hugging) being aversive and potentially deadly, and in others being perceived as potential threats to survival (Schimmenti et al., 2020), ultimately affecting one's feelings/experiences of social safeness. Research has indeed begun to emerge showing that paranoia and conspiratorial thinking are associated with COVID‐19 (Larsen et al., 2020) and social safeness is likely in short supply. Social safeness is posited to be a distinct affective dimension (from positive and negative affect) and defined as a warm, soothing affective state associated with caring and attachment processes (Armstrong et al., 2020), related to feeling positively socially connected to others and feeling safe and supported in close social relationships (Kelly et al., 2012). Social safeness is suggested to be emotion‐regulation process and was found to be a unique predictor of stress (Armstrong et al., 2020) and hence might act as a buffer against poor mental health.

There is growing consensus that the restrictions to human interaction and resultant social isolation, termed the ‘loneliness pandemic’ (Palgi et al., 2020), posed by the uncertainty of living with this new pathogen are a severe risk to the mental health of the general population (Prout et al., 2020; World Health Organization (WHO), 2020). The implementation of lockdown measures has significantly impacted mental health, with increasing cases or exacerbation of stress, depression, anxiety, loneliness and sleep problems in the general population (AL van Tilburg et al., 2020; Gloster et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Murphy et al., 2020; Serafini et al., 2020; Wang, Pan, et al., 2020; Wang, Zhang, et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2020). Pervasive and uncontrolled fears related to COVID‐19 have been associated with poor mental health indicators (e.g., Ahorsu et al., 2020; Bitan et al., 2020; Fitzpatrick et al., 2020; Kanovsky & Halamová, 2020). Additionally, research has revealed that psychosocial factors aggravated by the COVID‐19 pandemic (such as stress, depression, loneliness and social support) may not only increase risk of infection after exposure to a virus (Cohen, 2021), but also impair the immune system's response to vaccination (Madison et al., 2021), which may therefore have implications for susceptibility to COVID‐19 and to the efficacy of the SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine.

Despite the impact of these unprecedented physical distancing measures on people's social lives and feelings of social safeness, it has been suggested that factors such as resilience and social support could have a protective role in coping with the current crisis (Serafini et al., 2020). Recent research has shown social connectedness to potentially buffer against the negative physical and mental health impact of the coronavirus pandemic, and promote resilience (Nitschke et al., 2020; Palgi et al., 2020; Saltzman et al., 2020). Hence, investigating reputed protective and risk factors that might either buffer or magnify the mental health effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic is critical and has been considered a research priority for mental health science (Holmes et al., 2020; Vinkers et al., 2020). Compassion is one such construct that is already known to play a fundamental protective role in mental states, emotion regulation and social relationships (Gilbert, 2020; Mascaro et al., 2020; Seppälä et al., 2017), and might thus emerge as a key protective factor against the pervasive impact of the pandemic on mental health. However, fears of compassion, which can be seen as an antithesis to the buffering effects of compassion, are known to increase vulnerability to psychological distress (Kirby et al., 2019), and might actually magnify the effect of mental health difficulties being experienced in the current pandemic context. The present study is part of a broader multinational longitudinal study looking at compassion, mental health and social safeness in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

In recent years, research has documented the major psychological, social and neurophysiological effects of compassion and compassion training on promoting well‐being, reducing mental health difficulties, and fostering prosocial behaviour (Di Bello et al., 2020; Gilbert, 2017a; Kim et al., 2020; Petrocchi & Cheli, 2019; Seppälä et al., 2017; Singer & Engert, 2019; Stevens & Woodruff, 2018; Weng et al., 2013). Although definitions of compassion may vary (e.g., Gilbert, 2017b; Mascaro et al., 2020), in evolutionary focused models (Gilbert, 2019, 2020), compassion has been conceptualised as a prosocial motivation that involves ‘the sensitivity to suffering in self and others, with a commitment to try to alleviate and prevent it’ (Gilbert, 2014, p. 19). According to this model, compassion operates through evolved psychological (e.g., social intelligence and competencies) and physiological (e.g., the myelinated vagus nerve, oxytocin) mechanisms that underpin caring motives and behaviour rooted in the mammalian care‐giving systems (Carter, 2014; Gilbert, 2020; Porges, 2007). Compassion involves two components: (1) a sensitivity and engagement with distress; and (2) competencies to alleviate distress in a way that is helpful not harmful (Gilbert, 2014). Compassion can also be seen as a multidimensional construct and a dynamic intra and interpersonal process that occurs in a social interactional context, in the sense that it can be directed inwards, in the form of self‐compassion and compassion received from others, and outwards, in the form of compassion given to others (Gilbert et al., 2011). These dimensions have been defined as the different ‘flows’ of compassion (for self, from others and for others), which whilst highly interactive, can also be independent (Gilbert, 2014; Gilbert et al., 2017). For example, one might be able to be compassionate towards others yet struggle with being self‐compassionate (Lopez et al., 2018).

An extensive literature supports the finding that self‐compassion is a buffer against psychological distress (see MacBeth & Gumley, 2012, for a review). However, the multidimensional flows of compassion for self, from others and for others, have been less researched, although evidence suggests they are protective factors against psychological distress (Gilbert et al., 2017; Lindsey, 2017; Matos, Duarte, Duarte, et al., 2017; Steindl et al., 2018). Indeed, in the context of COVID‐19, both self‐compassion as a unidimensional construct (Jiménez et al., 2020; Kavaklı et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021), and the flows of compassion as a multidimensional construct (Matos, McEwan, et al., 2021) have been shown to be protective factors against psychological distress. In the same multinational study across 21 countries as the current study, Matos, McEwan, et al. (2021) found compassion for self was a reliable moderator between the perceived threat of COVID‐19 and lower psychological distress. Whilst compassion from others was a consistent moderator between fears of contracting COVID‐19 and higher social safeness.

Despite the benefits of the three flows of compassion to psychological well‐being and mental health (Kirby, Tellegen, et al., 2017), many individuals are unable to activate or use caring and compassionate motivational systems and affect regulators (Ebert et al., 2018), and can develop and experience fears of giving and receiving compassion (Gilbert et al., 2011; Gilbert & Mascaro, 2017). Fears of compassion might include the belief that compassion is weak or self‐indulgent, or that one will become too distressed or unable to cope, or that others, or indeed oneself, do not deserve compassion (Gilbert et al., 2011). Fears of compassion are seen as inhibitors that prevent compassionate motivation being ‘turned‐on’ or ‘acted on’, in that the signal of suffering is either not noticed/avoided or does not result in an action to prevent or alleviate that suffering. Fears of compassion then inhibit an individual's ability to activate compassionate motivational systems across the three flows, which negatively affects their physiological and psychological health and well‐being (Kirby, Doty, et al., 2017).

A recent meta‐analysis (Kirby et al., 2019) found that fears of self‐compassion and fears of receiving compassion from others had significant moderate associations with mental health outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, stress and well‐being, and vulnerability factors, such as self‐criticism and shame. These associations were even stronger in clinical populations struggling with a diagnosed mental health difficulty. Research has also revealed that fears of compassion predict paranoid ideation about other people as potential threats, and that fears of compassion for self and from others can mediate the relationship between adverse events and paranoid ideation (Matos, Duarte, & Pinto‐Gouveia, 2017). Thus, higher fears of compassion, especially for self and from others, may result in poorer psychosocial wellbeing outcomes during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Helpfully, fears of compassion can be diminished with training. For example, Fox et al. (2020) found that fears of compassion improved following Compassionate Mind Training (CMT) and these effects predicted further improvements in self‐reassurance, self‐criticism, shame and psychological distress. Another study demonstrated that a brief CMT reduced fears of compassion for self, for others and from others (Matos, Duarte, Duarte, et al., 2017) and that these fears (in particular for self and from others) mediated changes in self‐criticism, shame, depression, stress and safe positive affect induced by the intervention (Matos, Duarte, et al., 2021). In support, Dupasquier et al. (2018) found compassion training weakened the link between fears of receiving compassion from others and perceived risks of disclosing distress.

In addition to exacerbating psychological distress, the pandemic and its associated social distancing restrictions are contributing to increased feelings of social isolation (Palgi et al., 2020). Hence, two key psychological outcomes to emerge from the pandemic are social isolation and poor mental health. Social isolation, in the form of insecure attachment styles (Basran et al., 2019) and a lack of social safeness (Carvalho et al., 2019; Dias et al., 2020; Kelly & Dupasquier, 2016) have consistently been associated with fears of self‐compassion and fears of receiving compassion from others. Furthermore, social anxiety disorder symptom severity was uniquely predicted by fears of receiving compassion (Merritt & Purdon, 2020). Because social safeness is consistently associated with fears of compassion and may represent an approach to social connection (where fears of compassion are likely to be inversely related and represent a withdrawal from social connection), this study will examine fears of compassion as a mediator between the fears of COVID‐19 and mental health and social safeness.

1.1. Aims

Considering the reports of elevated psychological distress (Rajkuman, 2020) and social isolation (Palgi et al., 2020) resulting from the COVID‐19 pandemic, and given the potential for fears of compassion (especially for self and from others) to predict psychological distress (Kirby et al., 2019) and a lack of social safeness (Kelly & Dupasquier, 2016), this study aimed to examine fears of compassion across the three flows (for self, from others and for others) and their relationships with mental health indicators and social safeness. Specifically, the current study aimed to examine whether fears of compassion would moderate the effects of perceived threat of COVID‐19 (i.e., fear and likelihood of contracting SARS‐Cov‐2) on symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress, and on feelings of social safeness, in a global adult population across 21 countries from Europe, Middle East, North America, South America, Asia and Oceania. It was hypothesized that fears of compassion for self and from others (more so than fears of compassion for others) would predict psychological distress and a lack of social safeness during the pandemic. Further, it was hypothesized that fears of compassion would magnify the relationship between the perceived threat of COVID‐19 and psychological distress and social safeness.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants and procedures

This study is part of a larger longitudinal multinational study exploring compassion, social connectedness and trauma resilience during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The research sample was collected in 23 countries through social and traditional media platforms and institutional emailing lists in each country using snowball sampling. The samples from Peru (N = 16) and Uruguay (N = 23) were excluded, given that inclusion criterion was a minimum of 30 participants per country. The total sample consisted of 21 countries with 4057 participants, mean age 41.45 (SD = 14.96), with 80.8% (N = 3279) women, 18.2% (N = 739) men, 0.4% (N = 15) other and 0.6% (N = 24) preferred not to respond: Argentine (N = 257), Australia (N = 109), Brazil (N = 299), Canada (N = 115), Chile (N = 282), China (N = 77), Columbia (N = 50), Cyprus (N = 38), Denmark (N = 141), France (N = 115), Great Britain (N = 268), Greece (N = 145), Italy (N = 160), Japan (N = 522), Mexico (N = 181), Poland (N = 82), Portugal (N = 394), Saudi Arabia (N = 256), Slovakia (N = 46), Spain (N = 392), United States of America (N = 128). For more details on sociodemographic information per country see Supporting Information S1.

The procedures of the current study complied with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Coimbra (UC; CEDI22.04.2020). The study used cross‐sectional data gathered between mid‐April 2020 and mid‐May 2020 across the 21 countries. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before they completed the study protocol in an online survey, after being informed about the study aims, procedures and the voluntary, anonymous and confidential nature of their participation. The online survey was produced by the research team in English and translated to 11 other languages using forward/backward procedures. If a self‐report questionnaire had already been validated for a particular language/country that version was used instead. The online surveys were hosted at the institutional account of the UC in the online platformhttps://www.limesurvey.org/pt/. The dissemination of the study across countries was supported by a website (https://www.fpce.uc.pt/covid19study/). The survey was self‐paced and took about 25 min to complete. There was no monetary compensation for completing the survey.

2.2. Measures

The online survey consisted of a set of questions assessing sociodemographic information (nationality, country of residence, age, gender) and self‐report questionnaires measuring perceived threat of COVID‐19, fears of compassion (for self, for others, from others), psychological distress (depression, anxiety and stress), and social safeness.

The Perceived Coronavirus Risk Scale (PCRS; Kanovsky & Halamová, 2020; adapted from Napper et al., 2012) is an eight‐item self‐report questionnaire that assesses participants' fear of getting infected with SARS‐Cov‐2 and encompasses two dimensions: Fear of Contraction (affective aspect) and Likelihood of Contraction (cognitive aspect). Participants are asked to rate on a five‐point Likert scale how much they agree with each sentence from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores represent higher perceived threat of COVID‐19. In the original study, Kanovsky and Halamová (2020) reported internal consistency to be acceptable (Fear of Contraction α = .72; Likelihood of Contraction α = .71). In the present study, internal consistency was acceptable (Fear of Contraction α = .70; Likelihood of Contraction α = .70).

Fears of Compassion Scales (FCS; Gilbert et al., 2011) are three scales that assess fears of compassion, one for each flow: (1) fears of feeling and expressing compassion for others (10‐items), (2) fears of receiving compassion from others (13‐items) and (3) fears of compassion for self (15‐items). Respondents are asked to rate on a five‐point Likert scale how much they agree with each statement, from 0 (do not agree at all) to 4 (completely agree). Higher scores represent higher fears of compassion. In the original study, Cronbach's alphas were .72 for FCS for others, .80 for FCS from others, and .83 for FCS self‐compassion (Gilbert et al., 2011). In the current study, internal consistencies ranged between .89 and .95 (FCS self‐compassion α = .93, FCS compassion for others α = .89, FCS compassion from others α = .95).

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS‐21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) is a 21‐item self‐report instrument that consists of three subscales measuring Depression, Anxiety and Stress (seven items per subscale). Participants are asked to rate how often each statement applied to them over the past week on a four‐point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much, or most of the time). Higher scores represent higher severity of symptoms. Lovibond and Lovibond (1995) reported the subscales internal consistency to range between excellent and good (Depression α = .91; Anxiety α = .84; Stress α = .90). In the present study internal consistency also ranged from good to excellent (Depression α = .91, Anxiety α = .87, Stress α = .88).

Social Safeness and Pleasure Scale (SSPS; Gilbert et al., 2008) is an 11‐item self‐report questionnaire that measures the extent to which people usually experience their social world as safe, warm and soothing and how connected they feel to others. Participants are asked to rate how often they feel as described in each sentence on a five‐point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost all the time). Higher scores represent higher perceived social safeness and connectedness to others. In the original study, internal consistency was excellent (α = .92). In the present study, internal consistency was also excellent (α = .94).

2.3. Data analysis

The structure of data (a set of multiple dependent variables) suggests that a multivariate multilevel model must be considered, at least for the three‐dimensional DASS‐21 scale. In spite of the fact that multivariate analysis increases the complexity in a multilevel context, it is a crucial tool which enables the performance of a single test of the joint effects of our independent variables on several dependent variables (Hox et al., 2017; Snijders & Bosker, 2012). Our study measured three different output variables (i.e., three dimensions of the DASS‐21: anxiety, depression and stress). Data were collected from respondents who were clustered within countries. It would be possible to fit three separate models, but the overall picture would have been lost. Therefore, multivariate multilevel analysis was preferable and it increases statistical power. Each of the models had three levels: measurements of dimensions of the DASS‐21 were the level 1 units, the respondents were the level 2 units, and the countries were the level 3 units.

The following statistical procedure for the three‐dimensional DASS‐21 was proceeded: (1) fitting six multilevel multivariate models, each with three dependent variables (depression, anxiety and stress): (a) PCRS fear of contraction as the predictor, FCS self‐compassion as the predictor, and their interaction (FCS self‐compassion being the moderator); (b) PCRS likelihood of contraction as the predictor, FCS self‐compassion as the predictor, and their interaction (FCS self‐compassion being the moderator); (c) PCRS fear of contraction as the predictor, FCS compassion for others as the predictor, and their interaction (FCS compassion for others being the moderator); (d) PCRS likelihood of contraction as the predictor, FCS compassion for others as the predictor, and their interaction (FCS compassion for others being the moderator); (e) PCRS fear of contraction as the predictor, FCS compassion from others as the predictor, and their interaction (FCS compassion from others being the moderator); (f) PCRS likelihood of contraction as the predictor, FCS compassion from others as the predictor, and their interaction (FCS compassion from others being the moderator); (2) for each model, we tested the fit of three nested models with the data by two likelihood‐ratio tests and information criteria AIC (Akaike information criterion) and BIC (Bayes Schwarz information criterion): (a) the first model was the multilevel model without taking into account three dimensions of the DASS‐21, and having two predictors without the moderation; (b) the second model was the multivariate multilevel model taking into account three dimensions of the DASS‐21, and having two predictors without the moderation; and finally, (c) the third model was the multivariate multilevel model taking into account three dimensions of the DASS‐21, and having two predictors with the moderation. Our hypothesis could have been retained if and only if (a) the second model had a better fit than the first one (taking into account dimensions of the DASS‐21 was justified—respondents provided different answers in different dimension of the DASS‐21, otherwise the use of the multivariate model was not warranted); (b) the third model had the better fit than the second one, in that adding moderation improved the fit. If not, only main effects (and no moderation) could have had an impact; (3) if the third model had the best fit, we would report and interpret its coefficient (p values would be corrected by Bonferroni procedure to account for multiple testing); (4) we also provided the graphical representations of effects.

Since the SSPS is a unidimensional scale the univariate multilevel model was sufficient. Two models were fitted: (a) PCRS fear of contraction as the predictor, and (b) PCRS likelihood of contraction as predictor, and both models contained the same set of three moderators: FCS self‐compassion, FCS compassion for others, and FCS compassion from others.

For statistical analyses we used the R programme version 4.0.3 (R Core Team, 2020), the package ‘lme4’ (Bates et al., 2015). The effects were displayed through the package ‘sjPlot’ (Lüdecke, 2018). As fixed effects, we entered the mean‐centred PTCS subscale scores in an interaction with the mean‐centred CEAS subscales scores for each dimension of DASS‐21. As random effects, we used intercepts for participants and countries for each dimension of DASS‐21. For mean centring we used the package ‘questionr’ (Barnier et al., 2017).

The R code syntax for the model is given in Supplementary Online Material 2. R 2 (‘variance explained’) statistics were used to measure the effect size of the model. However, there is no consensus as to the most appropriate definition of R 2 statistics in relation to mixed‐effect models (Edwards et al., 2008; Jaeger et al., 2016; LaHuis et al., 2014; Nakagawa & Schielzeth, 2013). Even though several methods for estimating the coefficient of determination (R 2) for mixed‐effect models are accessible, the estimation of R 2 marginal and R2 conditional in the package ‘MuMIn’ (Barton, 2015) was performed. The marginal R2 is the proportion of variability explained by the fixed effects/predictors, the conditional R2 is the proportion of variability explained by both fixed and random effects (differences between respondents and differences between countries).

3. RESULTS

Table 1 presents the likelihood‐ratio tests and information criteria AIC and BIC.

TABLE 1.

The likelihood‐ratio tests and information criteria AIC and BIC for the different models

| Model | Predictor | Moderator | Deviance | χ2 (df) | p value | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 66,258 | 66,268 | 66,305 | ||||

| 1b | Fear of contraction | Fear of compassion for self | 62,552 | 3,706(14) | <.001 | 62,590 | 62,731 |

| 1c | 62,481 | 71 (3) | <.001 | 62,525 | 62,688 | ||

| 2a | 66,393 | 66,403 | 66,440 | ||||

| 2b | Likelihood of contraction | Fear of compassion for self | 62,744 | 3,649 (14) | <.001 | 62,782 | 62,923 |

| 2c | 62,732 | 13 (3) | NS | 62,776 | 62,939 | ||

| 3a | 67,073 | 67,083 | 67,120 | ||||

| 3b | Fear of contraction | Fear of compassion for others | 63,505 | 3,569 (14) | <.001 | 63,543 | 63,684 |

| 3c | 63,482 | 23 (3) | <.001 | 63,526 | 63,689 | ||

| 4a | 67,217 | 67,227 | 67,264 | ||||

| 4b | Likelihood of contraction | Fear of compassion for others | 63,706 | 3,512 (14) | <.001 | 63,744 | 63,884 |

| 4c | 63,696 | 10 (3) | NS | 63,740 | 63,903 | ||

| 5a | 66,466 | 66,476 | 66,513 | ||||

| 5b | Fear of contraction | Fear of compassion from others | 62,808 | 3,658 (14) | <.001 | 62,846 | 62,987 |

| 5c | 62,755 | 52 (3) | <.001 | 62,799 | 62,962 | ||

| 6a | 66,599 | 66,609 | 66,646 | ||||

| 6b | Likelihood of contraction | Fear of compassion from others | 62,998 | 3,601 (14) | <.001 | 63,036 | 63,177 |

| 6c | 62,965 | 34 (3) | <.001 | 63,009 | 63,172 |

As we can see in Table 1, all multivariate models (b‐models) consistently had a better fit than models that did not take dimensionality into account. However, only some models with FOCS as moderators (1c, 3c, 5c and 6c) had a better fit than models without moderation.

3.1. Fears of compassion for self

The coefficients of best fitting models for fears of self‐compassion (1c and 2b) are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Coefficients of the best‐fitting models for fear of compassion for self

| Fixed effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1c | Main effects | Moderation | |

| β [95% CI] | Fear of contraction | Fear of compassion for self | Fear:For self |

| Anxiety | 0.32 [0.29:0.36]*** | 0.12 [0.11:0.13]*** | 0.013 [0.010:0.016]*** |

| Depression | 0.19 [0.15:0.24]*** | 0.21 [0.20:.22]*** | 0.009 [0.005:0.012]*** |

| Stress | 0.35 [0.30:0.39]*** | 0.16 [0.14:0.17]*** | 0.008 [0.004:0.011]*** |

| Random effects | |||

| σ 2 | Respondents | Countries | |

| Anxiety | 6.86 | 9.67 | Residual = 4.49 |

| Depression | 11.24 | 23.00 | R 2 (marginal) = .114 |

| Stress | 12.32 | 38.36 | R 2 (conditional) = ..896 |

| Model 2b | Main effects | Moderation | |

| β [95% CI] | Likelihood of contraction | Fear of compassion for self | Likelihood:For self |

| Anxiety | 0.16 [0.13:0.20]*** | 0.14 [0.13:0.15]*** | N/A |

| Depression | 0.12 [0.08:0.16]*** | 0.22 [0.21:0.23]*** | N/A |

| Stress | 0.23 [0.19:0.27]*** | 0.17 [0.15:0.18]*** | N/A |

| Random effects | |||

| σ 2 | Respondents | Countries | |

| Anxiety | 7.70 | 10.23 | Residual = 4.41 |

| Depression | 11:58 | 22.39 | R 2 (marginal) = .103 |

| Stress | 12.92 | 38.96 | R 2 (conditional) = .900 |

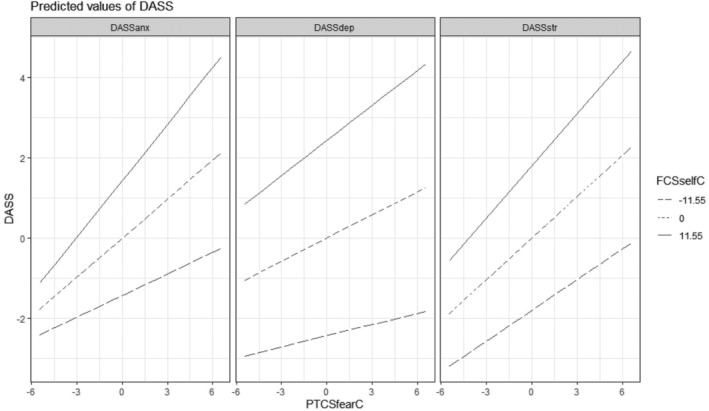

The main effects of fear of contraction on depression, anxiety and stress were all significant (and positive). The main effects of fears of self‐compassion on all three dimensions of the DASS‐21 were all significant as well (and positive as well). Interaction effects were significant in all three dimensions of the DASS‐21 indicating that fears of self‐compassion significantly moderate the impact of the fear of contraction on depression, anxiety and stress, across all countries. The variability among respondents was lowest in anxiety, and so was the variability among countries, which was in general larger than the individual variability, particularly in depression and stress. Figure 1. displays marginal effects of moderation of fears of self‐compassion in the case of fear of contraction: all slopes for subjects scoring highly in fears of self‐compassion (green) were steeper than other slopes, therefore fears of self‐compassion magnifies the impact of fear of contraction on depression, anxiety and stress, with the largest effect of moderation (the least parallel lines) being for anxiety, followed by depression and stress.

FIGURE 1.

Marginal effects of moderation of the fear of self‐compassion in the case of fear of contraction

A similar pattern was present when the predictor was likelihood of contraction, but only main effects were significant (and weaker). Therefore, fears of self‐compassion did not significantly moderate the impact of the likelihood of contraction on the DASS dimensions.

3.2. Fears of compassion for others

In Table 3, coefficients of best fitting models for compassion for others (3c and 4b) are presented.

TABLE 3.

Coefficients of the best‐fitting models for fear of compassion for others

| Fixed effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 3c | Main effects | Moderation | |

| β [95% CI] | Fear of contraction | Fear of compassion for others | Fear:For others |

| Anxiety | 0.40 [0.36:0.44]*** | 0.002 ns | 0.010[0.08:0.12] *** |

| Depression | 0.27 [0.22:0.32]*** | 0.13 [0.12:0.15] *** | 0.005[−0.01:0.10] |

| Stress | 0.40 [0.36:0.45]*** | 0.10[0.08:0.12] | 0.004[−0.01:0.009] |

| Random effects | |||

| σ 2 | Respondents | Countries | |

| Anxiety | 8.41 | 9.66 | Residual = 4.49 |

| Depression | 15.42 | 23.14 | R 2 (marginal) = .050 |

| Stress | 14.62 | 38.43 | R 2 (conditional) = .896 |

| Model 4b | Main effects | Moderation | |

| β [95% CI] | Likelihood of contraction | Fear of compassion for others | Likelihood:For others |

| Anxiety | 0.20 [0.17:0.24]*** | 0.10 [0.09:0.12]*** | N/A |

| Depression | 0.18 [0.14:0.23]*** | 0.15 [0.13:0.17]*** | N/A |

| Stress | 0.28 [0.23:0.32]*** | 0.12 [0.10:0.14]*** | N/A |

| Random effects | |||

| σ 2 | Respondents | Countries | |

| Anxiety | 9.97 | 10.02 | Residual = 3.66 |

| Depression | 16.53 | 23.32 | R 2 (marginal) = .037 |

| Stress | 16.00 | 38.77 | R 2 (conditional) = .916 |

The main effects of fear of contraction on depression, anxiety and stress were again all significant (and positive), but the main effect of the fears of compassion for others was significant (and positive) only in depression. However, interaction effects were significant only for the anxiety subscale, revealing that fears of compassion for others moderate the impact of fear of contraction on anxiety, but not on the other two DASS‐21 dimensions (across all countries). The variability among respondents was again lowest in anxiety, and so was the variability among countries, which was larger than the individual variability, in both depression and stress. A slightly different pattern was present for the predictor the likelihood of contraction, where all main effects were significant (likelihood of contraction and fears of compassion for others). Fears of compassion for others did not significantly moderate the impact of the likelihood of contraction on the DASS‐21 dimensions.

3.3. Fear of compassion from others

Table 4 presents the coefficients of best fitting models for compassion from others (5c and 6c).

TABLE 4.

Coefficients of best‐fitting models for fear of compassion from others

| Fixed effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 5c | Main effects | Moderation | |

| β [95% CI] | Fear of contraction | Fear of compassion from others | Fear:From others |

| Anxiety | 0.33 [0.29:0.37]*** | 0.13 [0.12:0.16]*** | 0.013 [0.009:0.16]*** |

| Depression | 0.20 [0.16:0.25]*** | 0.22 [0.21:0.24]*** | 0.009 [0.004:0.013]*** |

| Stress | 0.35 [0.31:0.40]*** | 0.17 [0.15:0.18]*** | 0.008 [0.004:0.012]* |

| Random effects | |||

| σ 2 | Respondents | Countries | |

| Anxiety | 7.29 | 9.38 | Residual = 4.44 |

| Depression | 12.34 | 22.74 | R 2 (marginal) = .103 |

| Stress | 12.87 | 38.17 | R 2 (conditional) = .897 |

| Model 6c | Main effects | Moderation | |

| β [95% CI] | Likelihood of contraction | Fear of compassion from others | Likelihood:From others |

| Anxiety | 0.17 [0.13:0.20]*** | 0.15 [0.14:0.16]*** | 0.008 [0.004:0.011]*** |

| Depression | 0.13 [0.08:0.17]*** | 023 [0.22:0.24]*** | 0.009[0.006:0.013] *** |

| Stress | 0.24 [0.19:0.28]*** | 0.18 [0.16:0.19]*** | 0.005[−0.01:0.09] |

| Random effects | |||

| σ 2 | Respondents | Countries | |

| Anxiety | 8.78 | 9.82 | Residual = 3.61 |

| Depression | 13.33 | 22.95 | R 2 (marginal) = .091 |

| Stress | 14.19 | 38.59 | R 2 (conditional) = .917 |

The main effects of fear of contraction and likelihood of contraction on depression, anxiety and stress were all significant (and positive), and so were all main effects of fears of compassion from others. The moderation effects were all significant (except of moderation between likelihood of contraction and stress subdimension), suggesting that fears of compassion from others moderate the impact of fear of contraction and likelihood of contraction on depression, anxiety and stress (across all countries), with one exception (out of six relations). The variability among respondents was lowest in anxiety, and so was the variability among countries, which was larger than the individual variability, both in depression and stress.

3.4. Social safeness

In Table 5, coefficients of two models with the social safeness and pleasure scale (SSPS) are presented.

TABLE 5.

Coefficients of the two models related to social safeness and connectedness (SPSS)

| Fixed effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Main effects | Moderation | |

| β [95% CI] | Intercept | Fear of compassion from self | Fear:For self |

| 40.49 [39.82:41.15]*** | −0.12 [−0.15:−0.09]*** | 0.001 ns | |

| Fear of contraction | Fear of compassion for others | Fear:For others | |

| 0.03 [−0.06:0.11] | 0.09 [0.05:.0.13] *** | 0.013 ns | |

| Fear of compassion from others | Fear:From others | ||

| −0.53 [−0.57:−0.49]*** | −0.009 [−0.021:0.003] | ||

| Random effects | |||

| σ 2 | Countries | Residual | R 2 (marginal) = .351 |

| 1.92 | 61.17 | R 2 (conditional) = .371 | |

| Model 2 | Fixed effects | ||

| Main effects | Moderation | ||

| β [95% CI] | Intercept | Fear of compassion from self | Likelihood:For self |

| 40.52 [39.85:41. 81]*** | −0.11 [−0.15:−0.08]*** | 0.009 ns | |

| Likelihood of contraction | Fear of compassion for others | Likelihood:For others | |

| −0.08 [−0.15:0.01] | 0.09 [0.05:0.13]*** | 0.013 ns | |

| Fear of compassion from others | Likelihood:From others | ||

| −0. 35 [−0.56:−0.496]*** | −0.026 [−0.037:−0.014] * | ||

| Random effects | |||

| σ 2 | Countries | Residual | R 2 (marginal) = .351 |

| 1.96 | 60.91 | R 2 (conditional) = .372 | |

The main effect of fear of contraction and the main effect of likelihood of contraction on SSPS were not significant, and all main effects for fears of self‐compassion, fears of compassion from others and fears of compassion from others were significant in both models. Only fears of compassion from others significantly moderated the effect of fear of contraction and likelihood of contraction on the SSPS, across all countries.

4. DISCUSSION

Taking together recent reports that the COVID‐19 pandemic has resulted in elevated psychological distress (Rajkuman, 2020) and social isolation (Palgi et al., 2020), and mounting evidence that fears of compassion (especially for self and from others) predict psychological distress (Kirby et al., 2019) and lack of social safeness (Kelly & Dupasquier, 2016), this study aimed to assess fears of compassion across the three flows (for self, from others and for others) and their relationships with psychological distress and social safeness in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Perceived threat of COVID‐19 was a significant predictor of higher psychological distress (depression, anxiety and stress). This is consistent with other studies which have shown that fears of COVID‐19 are related to poor mental health indicators (e.g., Ahorsu et al., 2020; Bitan et al., 2020; Fitzpatrick et al., 2020; Kanovsky & Halamová, 2020; Matos, McEwan, et al., 2021). However, perceived threat of COVID‐19 did not predict social safeness when we control for fears of compassion for self, for others, and from others. So, as far as social safeness is concerned, fears of compassion are more important than the coronavirus threat itself. This clarifies research indicating that loneliness and social isolation are prevalent in the context of COVID‐19 pandemic (Lee et al., 2020; Palgi et al., 2020; Saltzman et al., 2020), highlighting the role of these fears of compassion in the experience of social safeness and connectedness to others.

Thus, it was hypothesized that fears of compassion for self and from others (more so than fears of compassion for others) would predict psychological distress (Kirby et al., 2019) and a lack of social safeness (Kelly & Dupasquier, 2016) during the pandemic. Indeed, in a related study (Matos, McEwan, et al., 2021) compassion for self and from others were highly associated with lower psychological distress and higher social safeness. In the current study, this hypothesis was supported with all three flows of fears of compassion predicting psychological distress (depression, anxiety and stress) and social safeness. This is consistent with previous findings that compassion as a multidimensional construct predicts psychological distress (Kirby et al., 2019) and social safeness (Kelly & Dupasquier, 2016) and is in accordance with a related study examining the flows of compassion in relation to COVID‐19 (Matos, McEwan, et al., 2021).

Given the findings from a related study (Matos, McEwan, et al., 2021) which found that self‐compassion moderated the relationship between perceived threat of COVID‐19 and psychological distress, whilst compassion from others moderated the relationship between fear of contraction of COVID‐19 and social safeness, it was hypothesized that fears of compassion would moderate the relationship between the perceived threat of COVID‐19 and psychological distress/social safeness. In the next sections we discuss the specific findings that partially support our hypothesis.

4.1. Fear of self‐compassion

Fears of self‐compassion moderated the impact of fear of contraction of COVID‐19 on symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress, whilst it only moderated the likelihood of contraction of COVID‐19 on anxiety. This suggests that fears of being compassionate to oneself magnify the effects of fear of contracting COVID‐19 on psychological distress and also strengthen the association between likelihood of contraction and anxiety. For example, when confronted with a threatening context, a person with high fears of self‐compassion might fear appearing weak or how that might be perceived in interrelational contexts, or might fear that self‐compassion would make them self‐indulgent or selfish, or perhaps too self‐pitying, and therefore may put on a brave face or shift to a more self‐attacking or self‐berating style, thus magnifying the effect of the fears of contraction on psychological distress. Thus, our results enrich the perspective that if compassion is crucial for emotional processing and affect regulation (Kirby, Doty, et al., 2017; Seppälä et al., 2017), then the inability to generate compassion for oneself poses one at greater risk to psychopathology, as one might be unable to self‐soothe and regulate difficult emotional states in the face of threatening situations (Gilbert, 2020; Gilbert et al., 2011).

This finding is consistent with Matos, McEwan, et al. (2021) which found self‐compassion moderated the impact of perceived threat of COVID‐19 on psychological distress, and with Matos, Duarte, and Pinto‐Gouveia (2017) finding that fears of self‐compassion mediated the relationship between adverse events and depression and anxiety. Although our study found that fears of self‐compassion significantly predicted diminished social safeness in the context of COVID‐19, which is in line with previous research reporting fears of self‐compassion to be negatively associated with social safeness (Kelly & Dupasquier, 2016), these fears did not moderate the impact of perceived threat of COVID‐19 on social safeness.

4.2. Fear of compassion from others

Fear of compassion from others moderated the impact of fear of contraction of COVID‐19 on depression, anxiety and stress, and additionally moderated the impact of likelihood of contraction on depression and anxiety (but not stress). In addition, fears of compassion from others emerged as a significant moderator between the impact of the likelihood of contraction and social safeness. So, it seems that being frightened and resistant to receiving compassion from others amplifies the impact of perceived threat of COVID‐19 on increased psychological distress and reduced feelings of social safeness. Fears of receiving compassion from others may create a state in which others are seen as threats, and therefore such fears magnify the negative effect of fears of contraction on social safeness in particular.

This is in support of previous research showing that fears of compassion from others was a significant mediator of the impact of adverse events on depression and anxiety symptoms (Matos, Duarte, & Pinto‐Gouveia, 2017), and amplified the depressogenic effect of self‐criticism (Hermanto et al., 2016). This is also consistent with Kirby et al. (2019) who found that fears of compassion for self and from others were both significant predictors of psychological distress. Although this is the first study to explore social safeness in the context of fears of compassion and COVID‐19, previous research found that individuals frightened of receiving compassion from others tend to experience an inability to feel safe and soothed by others (Kelly & Dupasquier, 2016). Fears of compassion from others were also found to be a mediator between adverse events and paranoid ideation, which can be seen as an indicator of lack of social safeness (Matos, Duarte, & Pinto‐Gouveia, 2017). Our findings are thus consistent with the notion that, from birth and throughout life, caring social relationships operate as key regulators of physiological and affective processes, engendering a sense of feeling socially safe in the world and producing greater wellbeing (Cacioppo et al., 2000; Gilbert, 2020). If one's capacity to access compassion from others is blocked and one is frightened or resistant of receiving care and support from others, then this might thwart opportunities for them to experience and learn how interpersonal social relating and affiliative behaviours can be a source of soothing, calmness and connection in times of loneliness and distress, such as the current pandemic (Kirby et al., 2019). Being fearful of compassion from others can hence hinder one's ability to regulate threat‐based emotional states, repair psychophysiological regulation, and restore a sense of feeling safe and connected to others (Gilbert, 2014; Gilbert et al., 2011), making them more vulnerable to psychological distress and to feel socially unsafe/disconnected in the face of threatening situations, such as the COVID‐19 pandemic.

4.3. Fear of compassion for others

Fear of compassion for others moderated the impact of the fear of contraction of COVID‐19 on anxiety only, and did not moderate the relationship between likelihood of contraction and psychological distress. This finding may again be related to the notion that during the COVID‐19 pandemic, others have become threats, fuelling fears of contraction, and therefore inhibiting compassion involving contact with others, either receiving compassion from others or offering compassion to others, resulting in increased anxiety. This is consistent with findings from the related study (Matos, McEwan, et al., 2021) which found compassion for others did not moderate the relationship, and previous findings which have generally found that fears of compassion for others has less impact on psychological distress (Kirby et al., 2019).

Overall, these results extend the findings from Matos, McEwan, et al. (2021) where self‐compassion was the only flow that emerged as a significant moderator in relation to mental health outcomes, and indicate that when going beyond compassion to consider the inhibitors of compassionate motivation, a distinct pattern of results emerges with the three flows of fears of compassion all magnifying the impact of perceived threat of COVID‐19 on psychological distress, across all 21 countries. Therefore, the inability to activate compassionate motivational systems across the three flows negatively affects psychological health and well‐being in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Furthermore, the pandemic and associated social distancing measures may contribute to heightened fear experiences, focused for example in others becoming potential threats or in one being potentially dangerous to others (Schimmenti et al., 2020), and seem to be related to increased paranoia and conspiratorial thinking (Larsen et al., 2020). Thus, under this global threat that is the COVID‐19 pandemic, understanding and addressing the factors underlying the experience fears of compassion might be relevant to promote psychosocial well‐being.

Whilst the course of the COVID‐19 pandemic will likely change over time, its effects on mental health and psychosocial well‐being are likely to persist well into the future (Prout et al., 2020). Thus, the implementation of community‐based strategies to support resilience and promote mental health in this period is critical (Serafini et al., 2020). The current study has demonstrated that fears of compassion magnify the pervasive effects of perceived threat of COVID‐19 on psychological distress and social safeness. One thing that distinguishes the pandemic from other large‐scale crises (e.g., natural disasters), is that other humans are seen as a potential source of threat and can become a source of suspicion and overt hostility. This makes COVID‐19 a challenging context when it comes to the facilitation of compassion. Nonetheless, compassion can be trained and cultivated, and compassion‐focused interventions could be used to reduce inhibitors of compassionate motivation and to protect against mental health difficulties during and following the pandemic. CMT in particular might be a suitable approach to address fears of compassion and promote well‐being and social safeness in this context. CMT is an evolutionary and biopsychosocial evidence‐based approach, developed as an intervention for the general public comprising psychoeducation and a set of core compassion and mindfulness practices taken from Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT; Gilbert, 2014; Gilbert & Choden, 2013). CMT is designed to activate and develop evolved, affiliative care‐focused motivational systems and emotions in order to down‐regulate threat‐focused systems and stimulate psychological and neurophysiological processes conductive to better emotion regulation, wellbeing, health and social relationships (Gilbert, 2014, 2020). CMT is centred around helping people to develop the competencies to courageously turn towards and engage with suffering in self and others, and learn a variety of skills linked to reasoning, mentalizing and emotional regulation, which make them more open to compassion and enable compassion motives to be translated into compassionate actions (Gilbert, 2014, 2020; Gilbert & Choden, 2013).

CMT seeks to cultivate a compassionate mind/self‐identity which is used to manage daily struggles and common difficulties, and includes the three interactive flows of compassion: the ability to be compassionate towards oneself and others, as well as to receive compassion from others. Importantly, CMT strives to directly address the common fears, blocks, and resistances to compassion through psychoeducation and a range of practices (Gilbert, 2014, 2020). CMT begins with psychoeducation on the definition of compassion and of its three ‘flows’ and includes the exploration of fears, blocks, and resistances to compassion (self to other, other to self and self‐compassion). People learn about the evolved nature of mind and body and how life's difficulties are linked to evolved processes linked to our ‘tricky brains’ and that are ‘not our fault’. CMT explores the complexity and evolved functions of emotions and how these cluster onto three emotion ‘systems’: (i) the threat system, related to seeking protection and safety with anxiety, anger and sadness being the key emotions attached to it; (ii) the drive system, which is linked to incentive and resource‐seeking; and (iii) the soothing system, which is about settling, non‐wanting and safeness. People learn that psychological distress can arise from the misbalance of those systems and how the soothing system can be cultivated to reduce the inhibitors to compassion, regulate distress, foster feelings of safeness and calmness (Gilbert, 2014; Gilbert & Choden, 2013). To do this, CMT incorporates a variety of evidence‐based physiological and psychological practices (e.g., attention training, mindfulness, soothing rhythm breathing, imagery and behavioural practices), which recruit various neuro circuits associated with compassion (Kim et al., 2020; Singer & Engert, 2019) and aim to balance the autonomic nervous system (e.g., via the stimulation of the parasympathetic, vagal system; Kirby, Doty, et al., 2017). Thus, CMT practices help people to enhance mind awareness and cultivate their soothing system with increased capacities to slow down and feel grounded in the body, and to down‐regulate threat processing and emotional states, for example, such as those associated with fears of offering or being the recipient of compassion in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

CMT has been shown effective in diminishing fears of compassion across the three flows with a positive impact on mental well‐being (Dupasquier et al., 2018; Fox et al., 2020; Matos, Duarte, Duarte, et al., 2017) and can be delivered online (McEwan & Gilbert, 2015; McEwan et al., 2018). Indeed, recent studies have documented that compassion‐focused interventions can ameliorate psychological distress in the specific context of the pandemic (Cheli et al., 2020; Schnepper et al., 2020). Moreover, psychological interventions that decrease anxiety and depression may boost immune responses to vaccines (Madison et al., 2021; Vedhara et al., 2019), and hence future research could investigate CMT as a possible facilitator of the efficacy of the SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines.

For wider impact among the general population, authorities and policy makers could implement compassionate social marketing and public health communications to reduce fears of COVID‐19 and resistances to compassion, and promote psychosocial wellbeing. For example, Heffner et al. (2021) found that prosocial public health messaging (e.g., ‘Help save our most vulnerable. Together, we can stop the coronavirus…’.) led to greater compliance with COVID‐19 lockdown measures, compared with threatening messages. Whilst Jordan et al. (2020) found that prosocial messaging (‘don't spread it’) rather than self‐interested messaging (‘don't get it’) lead to greater willingness to comply with lockdown measures. Further specific examples of social marketing slogans such as ‘Be kind’, ‘We will get through this together’, ‘Stand together. Stay apart’ are detailed in Lee (2020).

4.4. Limitations and future directions

As with any multinational study there may be differences across countries which can affect the results. In this case the differences in rates of COVID‐19 and Government responses to the pandemic may affect variables such as psychological distress and the amount of social contact people receive in different countries. It is therefore reassuring that the results of this study were found to be consistent across countries. It is also important to note that convenience samples were used and, therefore, these are not representative of the countries' populations. For example, more female participants consented to take part in the study, and there was no representation from the continent of Africa. Thus, in the future research should attempt to recruit more men and greater efforts should be made to collect data across all continents. Finally, the cross‐sectional nature of the study prevents the establishment of causality, although the study is currently collecting longitudinal data throughout the pandemic.

4.5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates the universal magnifying effects of fears of compassion, in particular fears of self‐compassion and of receiving compassion from others, on the damaging impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health and social safeness. Addressing the harmful effects of the pandemic on mental health and social relationships (e.g., Gloster et al., 2020; Palgi et al., 2020) should be treated as a public health priority. Public health policy‐makers and providers should adopt compassion focused interventions and communications to reduce fears of compassion and thus foster resilience and mental wellbeing during and in the aftermath of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Supporting information

Table S1. Research samples with sociodemographic information

Data S1. Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Compassionate Mind Foundation for their support in the implementation of the project. We would also like to thank the Tages Onlus for the scientific and organisational support and Giselle Kraus, in the Italian and Canadian arms of this study respectively.

The overall research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not‐for‐profit sectors. This work was supported by the Center for Research in Neuropsychology and Cognitive Behavioral Intervention (CINEICC) funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (M.M., Strategic Project UID/PSI/00730/2020). The Slovak arm of this study was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency (J.H. & M.K.; Contract no. PP‐COVID‐20‐0074) and the Vedecká grantová agentúra VEGA (J.H.; Grant 1/0075/19). The Canadian arm of the study was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Insight Grant (A.K., ref. 435‐2017‐0062). The Brazilian arm was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (P.L.‐S.; SFRH/BD/130677/2017) and the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (M.S.O.; Scientific Productivity Grant).

Matos, M. , McEwan, K. , Kanovský, M. , Halamová, J. , Steindl, S. R. , Ferreira, N. , Linharelhos, M. , Rijo, D. , Asano, K. , Gregório, S. , Márquez, M. G. , Vilas, S. P. , Brito‐Pons, G. , Lucena‐Santos, P. , da Silva Oliveira, M. , de Souza, E. L. , Llobenes, L. , Gumiy, N. , Costa, M. I. … Gilbert, P. (2021). Fears of compassion magnify the harmful effects of threat of COVID‐19 on mental health and social safeness across 21 countries. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(6), 1317–1333. 10.1002/cpp.2601

Funding information Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, Grant/Award Numbers: SFRH/BD/130677/2017, UID/PSI/00730/2020; Slovak Research and Development Agency, Grant/Award Number: PP‐COVID‐20‐0074; Vedecká grantová agentúra MšVVaš SR a SAV, Grant/Award Number: 1/0075/19; Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Insight Grant, Grant/Award Number: 435‐2017‐0062; Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, MM, upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Ahorsu, D. K. , Lin, C.‐Y. , Imani, V. , Saffari, M. , Griffiths, M. D. , & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). The fear of COVID‐19 scale: Development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AL van Tilburg, M. , Edlynn, E. , Maddaloni, M. , van Kempen, K. , Díaz‐González de Ferris, M. , & Thomas, J. (2020). High levels of stress due to the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic among parents of children with and without chronic conditions across the USA. Children (Basel, Switzerland), 7(10), 193. 10.3390/children7100193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, B. F. , Nitschke, J. P. , Bilash, U. , & Zuroff, D. C. (2020). An affect in its own right: Investigating the relationship of social safeness with positive and negative affect. Personality and Individual Differences., 168. 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109670 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnier, J. , Briatte, F. , & Larmarange, J. (2017). Functions to make surveys processing easier. Package ‘questionr’, Version 0.6.2. Retrieved from: https://juba.github.io/questionr/

- Barton, K. (2015) Package ‘MuMIn’. Model selection and model averaging based on information criteria. R package version 1.15.11.

- Basran, J. , Pires, C. , Matos, M. , McEwan, K. , & Gilbert, P. (2019). Styles of leadership, fears of compassion, and competing to avoid inferiority. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2460. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D. , Maechler, M. , Bolker, B. , & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed‐effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bitan, D. T. , Grossman‐Giron, A. , Bloch, Y. , Mayer, Y. , Shiffman, N. , & Mendlovic, S. (2020). Fear of COVID‐19 scale: Psychometric characteristics, reliability and validity in the Israeli population. Psychiatry Research, 113100. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J. T. , Berston, G. G. , Sheridan, J. F. , & McClintock, M. K. (2000). Multilevel integrative analysis of human behavior: Social neuroscience and the complementing nature of social and biological approaches. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 829–843. 10.1037/0033-2909.126.6.829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, C. S. (2014). Oxytocin pathways and the evolution of human behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 17–39. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, S. A. , Pinto‐Gouveia, J. , Gillanders, D. , & Castilho, P. (2019). Obstacles to social safeness in women with chronic pain: The role of fears of compassion. Current Psychology.. 10.1007/s12144-019-00489-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheli, S. , Cavalletti, V. , & Petrocchi, N. (2020). An online compassion‐focused crisis intervention during COVID‐19 lockdown: A cases series on patients at high risk for psychosis. Psychosis, 1–4, 12, 359–362. 10.1080/17522439.2020.1786148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. (2021). Psychosocial vulnerabilities to upper respiratory infectious illness: Implications for susceptibility to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(1), 161–174. 10.1177/1745691620942516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bello, M. , Carnevali, L. , Petrocchi, N. , Thayer, J. F. , Gilbert, P. , & Ottaviani, C. (2020). The compassionate vagus: A meta‐analysis on the connection between compassion and heart rate variability. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 116, 21–30. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias, B. S. , Ferreira, C. , & Trindade, I. A. (2020). Influence of fears of compassion on body image shame and disordered eating. Eating and Weight Disorders, 25, 99–106. 10.1007/s40519-018-0523-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupasquier, J. R. , Kelly, A. C. , Moscovitch, D. A. , & Vidovic, V. (2018). Practicing self‐compassion weakens the relationship between fear of receiving compassion and the desire to conceal negative experiences from others. Mindfulness, 9(2), 500–511. 10.1007/s12671-017-0792-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, A. , Edel, M.‐A. , Gilbert, P. , & Brüne, M. (2018). Endogenous oxytocin is associated with the experience of compassion and recalled upbringing in borderline personality disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 35, 50–57. 10.1002/da.22683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, L. J. , Muller, K. E. , Wolfinger, R. D. , Qaqish, B. F. , & Schabenberger, O. (2008). An R2 statistic for fixed effects in the linear mixed model. Statistics in Medicine, 27(29), 6137–6157. 10.1002/sim.3429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, K. M. , Harris, C. , & Drawve, G. (2020). Fear of COVID‐19 and the mental health consequences in America. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12, S17–S21. 10.1037/tra0000924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J. , Cattani, K. , & Burlingame, G. M. (2020). Compassion focused therapy in a university counseling and psychological services center: A feasibility trial of a new standardized group manual. Psychotherapy Research. 10.1080/10503307.2020.1783708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53, 6–41. 10.1111/bjc.12043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. (Ed.) (2017a). Compassion: Concepts, research and applications. Routledge. 10.4324/9781315564296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. (2017b). Compassion: Definitions and controversies. In Gilbert P. (Ed.), Compassion: Concepts, research and applications (pp. 3–15). Routledge. 10.4324/9781315564296-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. (2019). Explorations into the nature and function of compassion. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 108–114. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. (2020). Compassion: From its evolution to a psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 3123. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. & Choden . (2013). Mindful compassion. Constable‐Robinson. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. , & Mascaro, J. (2017). Compassion: Fears, blocks, and resistances: An evolutionary investigation. In Seppälä E. M., Simon‐Thomas E., Brown S. L., Worline M. C., Cameron L., & Doty J. R. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Compassion Science (pp. 399–420). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. , McEwan, K. , Mitra, R. , Franks, L. , Richter, A. , & Rockliff, H. (2008). Feeling safe and content: A specific affect regulation system? Relationship to depression, anxiety, stress, and self‐criticism. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(3), 182–191. 10.1080/17439760801999461 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. , McEwan, K. , Matos, M. , & Rivis, A. (2011). Fears of compassion: Development of three self‐report measures. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 84, 239–255. 10.1348/147608310X526511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. , Catarino, F. , Duarte, C. , Matos, M. , Kolts, R. , Stubbs, J. , Ceresatto, L. , Duarte, J. , Pinto‐Gouveia, J. , & Basran, J. (2017). The development of compassionate engagement and action scales for self and others. Journal of Compassionate Health Care, 4(1), 1–24. 10.1186/s40639-017-0033-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gloster, A. T. , Lamnisos, D. , Lubenko, J. , Presti, G. , Squatrito, V. , Constantinou, M. , Nicolaou, C. , Papacostas, S. , Aydın, G. , Chong, Y. Y. , Chien, W. T. , Cheng, H. Y. , Ruiz, F. J. , Garcia‐Martin, M. B. , Obando‐Posada, D. P. , Segura‐Vargas, M. A. , Vasiliou, V. S. , McHugh, L. , Höfer, S. , … Karekla, M. (2020). Impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health: An international study. PLoS One, 15(12), e0244809. 10.1371/journal.pone.0244809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, J. , Vives, M.‐L. , & Feldman‐Hall, O. (2021). Emotional responses to prosocial messages increase willingness to self‐isolate during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences, 170. 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanto, N. , Zuroff, D. C. , Kopala‐Sibley, D. C. , Kelly, A. C. , Matos, M. , & Gilbert, P. (2016). Ability to receive compassion from others buffers the depressogenic effect of self‐criticism: A cross‐cultural multi‐study analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 324–332. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, E. A. , O'Connor, R. C. , Perry, V. H. , Tracey, I. , Wessely, S. , Arseneault, L. , Ballard, C. , Christensen, H. , Cohen Silver, R. , Everall, I. , Ford, T. , John, A. , Kabir, T. , King, K. , Madan, I. , Michie, S. , Przybylski, A. K. , Shafran, R. , Sweeney, A. , … Bullmore, E. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID‐19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry., 7, 547–560. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox, J. J. , Moerbeek, M. , & Van de Schoot, R. (2017). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications (3rd ed.). Routledge. 10.4324/9781315650982 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, B. C. , Edwards, L. J. , Das, K. , & Sen, P. K. (2016). An R2 statistic for fixed effects in the generalized linear mixed model. Journal of Applied Statistics, 44(6), 1086–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, O. , Sánchez‐Sánchez, L. C. , & García‐Montes, J. M. (2020). Psychological impact of covid‐19 confinement and its relationship with meditation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 6642. 10.3390/ijerph17186642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, J. , Yoeli, E. , & Rand, D. (2020). Don't get it or don't spread it? Comparing self‐interested versus prosocially framed COVID‐19 prevention messaging. PsyArXiv. 10.31234/osf.io/yuq7x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanovsky, M. , & Halamová, J. (2020). Perceived threat of the coronavirus and the role of trust in safeguards: A case study in Slovakia. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 554160. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.554160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavaklı, M. , Ak, M. , Uğuz, F. , & Türkmen, O. O. (2020). The mediating role of self‐compassion in the relationship between perceived COVID‐19 threat and death anxiety. Turkish J Clinical Psychiatry, 23, 15–23. 10.5505/kpd.2020.59862 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, A. C. , & Dupasquier, J. (2016). Social safeness mediates the relationship between recalled parental warmth and the capacity for self‐compassion and receiving compassion. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 157–161. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, A. C. , Zuroff, D. C. , Leybman, M. J. , & Gilbert, P. (2012). Social safeness, received social support, and maladjustment: Testing a tripartite model of affect regulation. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36, 815–826. 10.1007/s10608-011-9432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. J. , Parker, S. L. , Doty, J. R. , Cunnington, R. , Gilbert, P. , & Kirby, J. N. (2020). Neurophysiological and behavioural markers of compassion. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1–9. 10.1038/s41598-020-63846-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, J. N. , Tellegen, C. L. , & Steindl, S. R. (2017). A meta‐analysis of compassion‐based interventions: Current state of knowledge and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 48(6), 778–792. 10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, J. N. , Doty, J. R. , Petrocchi, N. , & Gilbert, P. (2017). The current and future role of heart rate variability for assessing and training compassion. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 40. 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, J. N. , Day, J. , & Sagar, V. (2019). The ‘flow’ of compassion: A meta‐analysis of the fears of compassion scales and psychological functioning. Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 26–39. 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaHuis, D. M. , Hartman, M. J. , Hakoyama, S. , & Clark, P. C. (2014). Explained variance measures for multilevel models. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 433–451. 10.1177/1094428114541701 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, E. M. , Donaldson, K. , & Mohanty, A. (2020). Conspiratorial thinking during COVID‐19: The roles of paranoia, delusion‐proneness, and intolerance to uncertainty. Preprint Manuscript. 10.31234/osf.io/mb65f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lee, C. M. , Cadigan, J. M. , & Rhew, I. C. (2020). Increases in loneliness among young adults during the covid‐19 pandemic and association with increases in mental health problems. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 67(5), 714–717. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, N. R. (2020). Reducing the spread of Covid‐19: A social marketing perspective. Social Marketing Quarterly., 26(3), 259–265. 10.1177/1524500420933789 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li, A. , Wang, S. , Cai, M. , Sun, R. , & Liu, X. (2021). Self‐compassion and life‐satisfaction among Chinese self‐quarantined residents during COVID‐19 pandemic: A moderated mediation model of positive coping and gender. Personality and Individual Differences, 170. 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey, S. (2017). Examining the psychometric properties of the compassionate engagement and action scales in the general population. Other thesis: University of Essex. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, A. , Sanderman, R. , Ranchor, A. V. , & Schroevers, M. J. (2018). Compassion for others and self‐compassion: Levels, correlates, and relationship with psychological well‐being. Mindfulness, 9, 325–331. 10.1007/s12671-017-0777-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond, S. H. , & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd. ed.). Sydney: Psychology Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdecke, D. (2018). sjPlot: Data visualization for statistics in social science. (R package version 2.6.1). Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sjPlot

- MacBeth, A. , & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta‐analysis of the association between self‐compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 545–552. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison, A. A. , Shrout, M. R. , Renna, M. E. , & Kiecolt‐Glaser, J. K. (2021). Psychological and behavioral predictors of vaccine efficacy: Considerations for COVID‐19. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 191–203. 10.1177/1745691621989243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascaro, J. S. , Florian, M. P. , Ash, M. J. , Palmer, P. K. , Frazier, T. , Condon, P. , & Raison, C. (2020). Ways of knowing compassion: How do we come to know, understand, and measure compassion when we see it? Frontiers in Psychology, 11. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.547241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M. , Duarte, J. , & Pinto‐Gouveia, J. (2017). The origins of fears of compassion: Shame and lack of safeness memories, fears of compassion and psychopathology. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 151(8), 804–819. 10.1080/00223980.2017.1393380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M. , Duarte, C. , Duarte, J. , Pinto‐Gouveia, J. , Petrocchi, N. , Basran, J. , & Gilbert, P. (2017). Psychological and physiological effects of compassionate mind training: A pilot randomized controlled study. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1699–1712. 10.1007/s12671-017-0745-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M. , McEwan, K. , Kanovský, M. , Halamová, J. , Steindl, S. , Ferreira, N. , Linharelhos, M. , Rijo, D. , Asano, K. , Gregório, S. , Márquez, M. , Vilas, S. Brito‐Pons, G. , Lucena‐Santos, P. , Oliveira, M. , Souza, E. , Llobenes, L. , Gumiy, N. , Costa, M. , … Gilbert, P. (2021). Compassion protects mental health and social safeness during the COVID‐19 pandemic across 21 countries. Manuscript under revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M. , Duarte, C. , Duarte, J. , Pinto‐Gouveia, J. , Petrocchi, N. , & Gilbert, P. (2021). Cultivating the compassionate self: An exploration of the mechanisms of change in compassionate mind training. Manuscript under revision. [Google Scholar]

- McEwan, K. , & Gilbert, P. (2015). A pilot feasibility study exploring the practicing of compassionate imagery exercises in a nonclinical population. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 89(2), 239–243. 10.1111/papt.12078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan, K. , Elander, J. , & Gilbert, P. (2018). Evaluation of a web‐based self‐compassion intervention to reduce student assessment anxiety. Interdisciplinary Education and Psychology, 2(6). 10.31532/InterdiscipEducPsychol.2.1.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, O. A. , & Purdon, C. L. (2020). Scared of compassion: Fear of compassion in anxiety, mood, and non‐clinical groups. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59(3), 354–368. 10.1111/bjc.12250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, D. , Williamson, C. , Baumann, J. , Busuttil, W. , & Fear, N. T. (2020). Exploring the impact of COVID‐19 and restrictions to daily living as a result of social distancing within veterans with pre‐existing mental health difficulties. BMJ military health, Advance online publication. 10.1136/bmjmilitary-2020-001622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, S. , & Schielzeth, H. (2013). A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed‐effects models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 4(2), 133–142. 10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00261.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]