Abstract

Objective

To understand medication, lifestyle, and clinical care changes of persons with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) during the first months (March 2020 through May 2020) of the COVID‐19 pandemic in the US.

Methods

Data were collected from adults with RA participating in FORWARD, The National Databank for Rheumatic Diseases observational registry, who answered COVID‐19 web‐based surveys in May 2020 and previously provided baseline characteristics and medication use prior to the US COVID‐19 pandemic. We compared medication changes by disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) exposure in logistic models that were adjusted for age, sex, comorbidities including pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases, education level, health insurance status, RA disease activity, fatigue, and polysymptomatic distress.

Results

Of 734 respondents, 221 (30%) reported medication changes. Among respondents who experienced a medication change, i.e., “medication changers/changers,” glucocorticoids (GCs) were more commonly used compared to respondents who did not experience a medication change (“non‐changers”) (33% versus 18%). Non‐hydroxychloroquine conventional DMARDs were less commonly used in changers compared to non‐changers pre–COVID‐19 (49% versus 62%), and changers reported more economic hardship during the COVID‐19 pandemic compared to non‐changers (23% versus 15%). While JAK inhibitor use was associated with the likelihood of a medication change, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.9 (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.0, 3.4), only pre‐COVID GC use remained a strong predictor for medication change in multivariable models (OR 3.0 [95% CI 1.9, 4.9]). Change in care was observed to have a significant association with pulmonary disease (OR 2.9 [95% CI 1.3, 6.5]), worse RA disease activity (OR 1.1 [95% CI 1.0, 1.1]), and GC use (OR 1.6 [95% CI 1.0, 2.5]). While the incidence of medication changes was the same before and after the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidance for the management of rheumatic disease in adult patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic were first published in April 2020, self‐imposed changes in medication were approximately twice as likely before publication of the guidelines, and physician‐guided changes were more likely after publication.

Conclusion

Persons with RA in the US made substantial medication changes during the first three months of the COVID‐19 pandemic, and changes among persons with RA after publication of the ACR guidance in April 2020 were made with increased physician guidance.

INTRODUCTION

In December 2019, the novel coronavirus SARS–CoV‐2 was identified in Wuhan, China. It was determined to be responsible for the outbreak of COVID‐19, which was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020. People with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases have been impacted during this pandemic through their greater risk of infection due to immune dysregulation, comorbidities, and immune‐modulating treatments (1, 2, 3), and at the same time, many of these immune‐modulating treatments (e.g., hydroxychloroquine [HCQ], glucocorticoids [GCs], interleukin‐1 [IL‐1] and IL‐6 inhibitors, JAK inhibitors) are being tested to prevent or treat COVID‐19 (4, 5, 6), which has caused some confusion and concerns about the actual risks posed to individuals with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (7). Additionally, changes in access to treatment and care have made it difficult for patients to understand how best to take care of their health with their conditions. From our recent survey during the first two weeks of the pandemic, almost half of patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases described significant disruptions to their rheumatology care, including disrupted or postponed appointments and self‐imposed or physician‐directed changes to medications (8).

SIGNIFICANCE & INNOVATIONS.

This is the first study to track changes in disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug use in people with rheumatoid arthritis during the US COVID‐19 pandemic.

Respondents made substantial medication changes during the first three months of the COVID‐19 pandemic, both with and without physician guidance.

Changes made after publication of the American College of Rheumatology guidance for the management of rheumatic disease in adult patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic were more likely to be made with physician guidance, though this finding was not statistically significant.

The pandemic has also presented particular challenges to rheumatologists in caring for their patients and managing their patients’ medical conditions. On April 13, 2020, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) provided the first clinical guidance on the treatment of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases including rheumatoid arthritis (RA) during the COVID‐19 pandemic, highlighting the need for patients to continue use of disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), control disease activity, and discontinue or reduce prednisone/GC steroid use. For those with documented or presumptive COVID‐19 infection, only HCQ and IL‐6 biologic agents were recommended for continued use (9).

Despite the multitude of new literature on COVID‐19 (10), there is still little known about treatment patterns at the individual level in the middle of this pandemic. For example, are individuals with RA and prescribers following ACR recommendations? Are persons with RA practicing social distancing? Are patients prescribed certain medications pre–COVID‐19 more likely to discontinue therapy than others? The aims of this study therefore were to fill important knowledge gaps concerning changes in treatment and to understand prescriber and patient behaviors around management of medications and disease condition during the pandemic. We set out to characterize lifestyle and clinical care changes, to understand the rationale for changes in medication, and to identify associations between those changes and baseline characteristics in persons with RA.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study population

The study population consisted of participants with RA ages 18 years or older enrolled in FORWARD, The National Databank for Rheumatic Diseases, an observational, multi‐disease patient registry (11). In addition to regular comprehensive semiannual questionnaires, participants were invited by email every two weeks between March 25, 2020 and June 2, 2020 to complete up to five supplementary COVID‐19 questionnaires. The results of the first March 25, 2020 survey were previously published (8).

For this analysis, we required completion of at least one semiannual questionnaire between January 2018 and January 2020 and at least one COVID‐19 questionnaire administered in May and June of 2020. Additionally, we required participants to be taking at least one of the following medications: HCQ, another conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARD), tumor necrosis factor inhibitor biologic DMARD (TNFi bDMARD), non‐TNF (NTNF) bDMARD, JAK inhibitor, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and/or GCs.

Questionnaires used in the FORWARD registry

Questionnaires used in the Forward Databank are administered semiannually every January and July and collect an array of patient‐reported outcomes. Information on treatments include doses, pill sizes, months taken, start and stop dates, discontinuation reasons, and side effects. Demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status, productivity, comorbidities, important medical events, health‐related quality of life, health symptoms, and disease‐specific outcomes measures are also assessed (11).

The COVID‐19 questionnaires used in these analyses were administered between May 6, 2020 and June 2, 2020 and focused on patient perspectives and experiences in the two weeks prior to questionnaire completion (see Supplementary Materials for COVID‐19 questionnaire used in the present study, available on the Arthritis Care & Research website at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.24611/abstract). Participants were asked about RA disease activity, development of new COVID‐19–related symptoms, testing for COVID‐19, changes in their rheumatology care, and lifestyle and economic changes caused by the pandemic.

Outcomes measures and variables of interest

Participants were characterized by demographic characteristics and clinical status, including age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, geographical area (urban versus rural setting), smoking status, body mass index, Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index (RDCI) (12), functional status (Health Assessment Questionnaire II [HAQ‐II]) (13), self‐reported disease activity (Patient Activity Scale II [PAS‐II]) (14), patient global health assessment, ratings of fatigue and pain, number of prior DMARDs received, polysymptomatic distress scale (PSD) (15), self‐reported disease activity at the time of supplementary questionnaire completion (low/moderate/severe), and economic changes as a result of the COVID‐19 pandemic (defined as any loss of employment, reduced household income, and/or loss of health insurance).

DMARDs were categorized in a mutually exclusive hierarchical manner, assigning each patient to their highest category following this sequence: no DMARDs, csDMARDs, TNFi bDMARDs, NTNF bDMARDs, and JAK inhibitors. Although HCQ is a csDMARD, its use was modeled separately as a binary indicator due to the attention it has received during the COVID‐19 pandemic and its common concomitant use to treat RA. Additionally, binary indicators for all drug groups, including NSAIDs and GCs, were used since patients could have been taking more than one drug simultaneously.

Patients were classified as “medication changers/changers” if they discontinued a medication, added other drugs, or changed the dose of a DMARD, GC, or NSAID after March 1, 2020. “Non‐changers” were those patients who indicated that they did not make any medication changes in the specified time period. The medication changers were subclassified by type of change. Data on the reasons for medication change, whether the change was self‐initiated or directed by a physician or other healthcare provider, and the dates for these drug changes were also collected. Patients were also categorized according to whether they reported any changes in rheumatology care or lifestyle.

Statistical analysis

Participants were described at baseline (based on the most recent semiannual observation) according to whether they did or did not report any changes in medications on the COVID‐19 questionnaire. Continuous and categorical variables were assessed by t‐test and chi‐square/Fisher’s exact test, respectively, as appropriate. Participants who reported changes in medications, healthcare, and lifestyle were described by DMARD group.

Logistic regression models were performed to assess the likelihood of changing medication and of reporting a change in care by DMARD group, adjusted for disease severity (PAS‐II), demographic characteristics, and clinical information. We used the following two models: Model 1 (DMARD group, HCQ, and GC) and Model 2 (Model 1 categories plus age, sex, presence of pulmonary disease, presence of cardiovascular disease, RDCI score [excluding pulmonary and cardiovascular disease], educational level, Medicare status, PAS‐II, presence of fatigue, history of prior DMARDs, and PSD score).

Sensitivity analyses were performed to ascertain the robustness of results: 1) the logistic models were estimated by entering each DMARD drug variable as an individual binary variable, allowing for overlapping use and 2) replacing PAS‐II with its 3 components HAQ‐II, pain, and patient global health assessment. Reasons for medication changes were reported by type of change, drug class, and whether changes were physician‐directed or self‐decided.

Finally, a time‐to‐event analysis was conducted to determine the time (in days) to a drug change from March 1, 2020. For those with no changes, the time from March 1, 2020 until the COVID‐19 questionnaire date was calculated. Kaplan‐Meier estimator and log‐rank tests were used to compare the different DMARD groups with respect to this outcome. This analysis also assessed how the publication of ACR guidance for rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease treatment in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic were associated with drug changes. Analyses were performed for those who made medication changes prior to publication of the ACR guidelines (March 1, 2020 to April 15, 2020) and those who made changes after publication (April 16, 2020 to questionnaire completion) by reason for change and physician‐directed status.

RESULTS

Patients

Of the 1,411 participants who completed at least one of the COVID‐19 questionnaires and a prior semiannual questionnaire, 734 had RA as their primary diagnosis and were receiving treatment with at least one of the drugs of interest (HCQ, other csDMARDs, TNFi bDMARDs, NTNF bDMARDs, JAK inhibitors, NSAIDs, or GCs). The time between prior FORWARD questionnaire completion and supplementary questionnaire completion was a median 8 months (interquartile 6–9 months), and the mean ± SD duration was 8 ± 3 months, with 98% of participants completed the supplementary questionnaires 4–12 months after completing the first FORWARD questionnaire.

Respondents had a mean age of 65 years, were mostly female (86%) and White (93%), with an average of 15 years of education (Table 1). In terms of the drug class distributions (each participant could be in more than one category), 21% of respondents were receiving HCQ therapy, 58% received other csDMARDs, 35% received TNFi bDMARDs, 27% received NTNF bDMARDs, and 10% received treatment with JAK inhibitors.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients who changed their usual medications compared to patients who did not have medication changes during the first three months of the US COVID‐19 pandemic*

| Overall, | Non‐changer, | Changer, | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 734 (100) | n = 513 (69.9) | n = 221 (30.1) | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, mean ± SD years | 64.7 ± 14.7 | 65.9 ± 10.4 | 61.9 ± 11.7 | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 104 (14.2) | 81 (15.8) | 23 (10.5) | 0.057 |

| White | 677 (93.4) | 474 (93.7) | 203 (92.7) | 0.625 |

| Education, mean ± SD years | 15.3 ± 2.1 | 15.3 ± 2.0 | 15.3 ± 2.2 | 0.917 |

| Married | 487 (68.1) | 348 (68.1) | 139 (68.1) | 0.993 |

| Rural setting | 145 (20.2) | 101 (20.1) | 44 (20.6) | 0.883 |

| Ever smoked | 281 (38.3) | 197 (38.4) | 84 (38.1) | 0.920 |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD kg/m2 | 28.5 ± 7.53 | 28.4 ± 7.54 | 28.6 ± 7.53 | 0.865 |

| Medicare health insurance | 316 (43.1) | 242 (47.2) | 74 (33.5) | 0.001 |

| Economic change† | 125 (17.0) | 75 (14.6) | 50 (22.6) | 0.008 |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||

| RDCI, mean ± SD | 2.4 ± 1.81 | 2.33 ± 1.85 | 2.38 ± 1.73 | 0.769 |

| Heart disease | 55 (7.7) | 37 (7.2) | 18 (8.8) | 0.465 |

| Pulmonary disease | 55 (7.5) | 36 (7.0) | 18 (8.8) | 0.408 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 45 (6.3) | 34 (6.6) | 11 (5.4) | 0.538 |

| Medications | ||||

| HCQ | 153 (20.8) | 106 (20.7) | 47 (21.3) | 0.853 |

| Other csDMARDs | 427 (58.2) | 318 (62.0) | 109 (49.3) | 0.001 |

| TNFi bDMARDs | 257 (35.0) | 181 (35.3) | 76 (34.4) | 0.816 |

| NTNFI bDMARDs | 199 (27.1) | 137 (26.7) | 62 (28.1) | 0.706 |

| JAK inhibitors | 70 (9.5) | 43 (8.4) | 27 (12.2) | 0.105 |

| Glucocorticoids | 165 (22.5) | 93 (18.1) | 72 (32.6) | <0.001 |

| NSAIDs | 277 (37.7) | 198 (38.6) | 79 (35.8) | 0.465 |

| Number of prior DMARDs, mean ± SD | 4.0 ± 2.1 | 3.9 ± 2.1 | 4.3 ± 2.0 | 0.029 |

| Other medication changes (non‐RA) | 83 (11.3) | 50 (9.8) | 33 (14.9) | 0.042 |

| Patient‐reported outcomes | ||||

| Disease activity‡ | ||||

| Low | 337 (46.1) | 375 (51.1) | 265 (35.8) | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 323 (44.2) | 105 (47.5) | 218 (42.8) | |

| Severe | 68 (9.3) | 37 (16.7) | 31 (6.1) | |

| Unknown | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Pain VAS, mean ± SD | 3.15 ± 2.49 | 3.05 ± 2.47 | 3.41 ± 2.53 | 0.087 |

| Patient global VAS, mean ± SD | 3.08 ± 2.31 | 2.92 ± 2.27 | 3.49 ± 2.38 | 0.003 |

| Fatigue VAS, mean ± SD | 3.58 ± 2.81 | 3.34 ± 2.76 | 4.20 ± 2.85 | <0.001 |

| HAQ‐II, mean ± SD | 0.76 ± 0.60 | 0.72 ± 0.59 | 0.85 ± 0.62 | 0.016 |

| PAS‐II, mean ± SD | 2.85 ± 1.94 | 2.73 ± 1.92 | 3.14 ± 1.96 | 0.021 |

| PSD scale, mean ± SD | 7.61 ± 5.67 | 7.21 ± 5.48 | 8.68 ± 6.05 | 0.009 |

Values are the number (%) unless indicated otherwise. bDMARDs = biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs; csDMARDs = conventional synthetic DMARDs; HAQ‐II = Health Assessment Questionnaire II; HCQ = hydroxychloroquine; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; NTNFI = non–tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; PAS‐II = Patient Activity Scale II; PSD = Polysymptomatic Distress; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; RDCI = Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index; VAS = visual analog scale.

Reported an economic impact from COVID‐19 (loss of employment, reduced household income, and/or loss of health insurance).

Self‐reported disease activity at the time of COVID‐19 questionnaire completion.

Of the 734 respondents with RA, 30.1% reported at least one medication change. Those who had changes were more likely to be younger and to have worse (higher) patient‐reported outcome measure values, including those on the HAQ‐II (0.9 versus 0.7) and PAS‐II (3.1 versus 2.7), compared to non‐changers. Changers also more frequently received treatment with GCs (33% versus 18%) and were less likely to have received non‐HCQ csDMARDs prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic (49% versus 62%). No differences in comorbidities were found between the two groups. Changers were more likely to have experienced a negative economic impact during this period (23% versus 15%) and to report nonrheumatic disease–related medication changes (15% versus 10%) (Table 1).

Medication, care, and lifestyle changes

Table 2 shows the percentage of respondents who reported medication changes, care changes, and lifestyle changes by type of change within each DMARD class. Participants may have experienced more than one change for the same DMARD group and may be allocated to more than one DMARD group.

Table 2.

Characterization of medication, care, and lifestyle changes by drug class*

| HCQ | Other csDMARDs | TNFi | NTNFi | JAK inhibitors | Glucocorticoids | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 153) | (n = 427) | (n = 257) | (n = 199) | (n = 70) | (n = 165) | |

| Medication change | ||||||

| Stopped/delayed | 6 (3.9) | 35 (8.2) | 17.6 (46) | 32 (15.9) | 12 (17.1) | 6 (3.6) |

| Added | 8 (5.2) | 6 (1.4) | 3.5 (9) | 6 (3.0) | 2 (2.9) | 33 (20.0) |

| Increased dose | 3 (2.0) | 12 (2.8) | 2.3 (6) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.4) | 13 (7.9) |

| Decreased dose | 3 (2.0) | 13 (3.0) | 0.4 (1) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (2.8) | 5 (3.0) |

| No change | 134 (87.6) | 366 (85.7) | 77.4 (199) | 160 (80.4) | 54 (77.1) | 112 (67.9) |

| Care change | ||||||

| Canceled/postponed appointments | 48 (31.0) | 142 (32.9) | 34.9 (91) | 56 (27.9) | 21 (30.0) | 40 (36.4) |

| Switched to teleconference | 55 (35.5) | 146 (33.8) | 31.0 (81) | 84 (41.8) | 33 (47.1) | 76 (46.1) |

| Could not reach rheumatology office | 7 (4.5) | 13 (3.0) | 3.1 (8) | 6 (3.0) | 4 (5.7) | 8 (4.9) |

| Could not obtain medication | 16 (10.3) | 18 (4.2) | 4.2 (11) | 11 (5.5) | 5 (7.1) | 9 (5.5) |

| Lifestyle change | ||||||

| Self‐quarantining† | 88 (56.8) | 233 (53.9) | 138 (52.9) | 112 (55.7) | 28 (39.4) | 102 (61.8) |

| Working/attending school from home | 35 (22.6) | 87 (20.1) | 63 (24.1) | 49 (24.4) | 18 (25.4) | 26 (15.8) |

| Canceled travel | 75 (48.4) | 200 (46.3) | 127 (48.7) | 88 (43.8) | 41 (57.8) | 63 (38.2) |

| Washing hands more often | 147 (94.8) | 412 (95.4) | 252 (96.6) | 189 (94.0) | 70 (98.6) | 158 (95.8) |

| Using hand sanitizer more often | 119 (76.8) | 323 (74.8) | 202 (77.4) | 162 (80.6) | 66 (93.0) | 127 (77.0) |

| Wearing a mask | 149 (96.1) | 417 (96.5) | 251 (96.2) | 188 (93.5) | 69 (97.2) | 158 (95.8) |

| Wearing gloves | 71 (45.8) | 194 (44.9) | 126 (48.3) | 97 (48.3) | 29 (41.4) | 68 (41.2) |

Values are the number (%). Patients can be in more than 1 drug category. csDMARDs = conventional synthetic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs; HCQ = hydroxychloroquine; NTNFi = non–tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Did not leave home at all in 2 weeks prior to COVID‐19 questionnaire completion, or only left for essential services (grocery/pharmacy/health care).

The percentage of respondents who had medication changes by DMARD group varied between 12% for HCQ and 23% for TNFi bDMARDs. By type, bDMARD (irrespective of mechanism of action) and JAK inhibitor users reported stopping or delaying the intake of that DMARD more often than csDMARDs or HCQ users (16–18% versus 4–8%). Further inspection of the JAK inhibitor treatment group showed that this difference was driven primarily by use of upadacitinib and baricitinib, which had 5 (71%) of 7 respondents stop or delay treatment, whereas tofacitinib had 7 (11%) of 64 respondents stop or delay treatment. Five percent of changers reported adding HCQ to their treatment regimen. All other medication changes related to adding drugs or changing dose were reported by <4% of patients of any DMARD group. The percentage of patients who did not report a change in treatment varied between 77% and 88%.

Regarding care changes, the percentage of respondents who canceled or postponed appointments was relatively uniform by DMARD group, varying between 28% and 35%. Respondents receiving treatment with NTNF bDMARD or JAK inhibitor reported switching to telehealth appointments more frequently than respondents who received HCQ and other csDMARDs (42% and 47% for NTNF users and JAK inhibitor users, respectively, as compared to 34–36% for HCQ/other csDMARDs users), and the TNFi bDMARDs treatment group had the lowest percentage of respondents who switched to telehealth appointments (31%). Between 3% to 6% of all respondents could not reach their rheumatology office, and 4–7% could not obtain their medication, except for HCQ users, who reported a higher frequency of being able to obtain medication as compared to the other treatment groups (10%).

Some types of lifestyle changes were adopted by almost all of the cohort regardless of DMARD treatment, including washing hands more often and wearing a mask (≥94% in all drug groups). Self‐quarantining was reported in more than half of the sample for all DMARD categories (53–56%), except for JAK inhibitor users (39%), but higher rates of hand sanitizer use and canceled travel were observed among JAK inhibitor users.

Association between medication changers and baseline characteristics

Results from the logistic models are shown for models including both medication changers and care changers (Table 3). In Model 1, medication changers seemed more likely to be JAK inhibitor users, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.9 (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.0, 3.4), though this result did not reach statistical significance and was attenuated in the multivariable Model 2. GC use was the only strong factor influencing the association between medication changes and baseline characteristics (OR 3.0 [95% CI 1.9, 5.2]).

Table 3.

Association between DMARD group and changes in medication/care as shown by regression models*

| Medication change | Care change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Model 1 (n = 734) |

Model 2 (n = 513) |

Model 1 (n = 734) |

Model 2 (n = 513) |

|

| DMARDs | ||||

| Referent csDMARDs | ||||

| No DMARDS | 1.59 (0.81, 3.11) | 1.21 (0.49, 3.01) | 0.84 (0.44, 1.60) | 0.72 (0.33, 1.59) |

| TNFi bDMARDS | 1.17 (0.74, 1.84) | 1.05 (0.58, 1.90) | 0.82 (0.54, 1.23) | 0.88 (0.53, 1.46) |

| NTNFi bDMARDs | 1.24 (0.77, 1.99) | 1.26 (0.68, 2.36) | 0.95 (0.62, 1.45) | 0.94 (0.55, 1.62) |

| JAK inhibitors | 1.85 (1.01, 3.38) | 1.55 (0.68, 3.51) | 1.21 (0.68, 2.17) | 1.13 (0.53, 2.40) |

| HCQ | 1.07 (0.70, 1.62) | 1.06 (0.62, 1.82) | 1.05 (0.72, 1.55) | 1.06 (0.66, 1.71) |

| Glucocorticoids | 2.14 (1.48, 3.09) | 3.02 (1.88, 4.85) | 1.71 (1.18, 2.48) | 1.59 (1.01, 2.50) |

| NSAIDs | – | 1.07 (0.69, 1.64) | – | 0.98 (0.67, 1.42) |

| Age, years | – | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) | – | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) |

| Male sex | – | 0.81 (0.43, 1.52) | – | 1.24 (0.73, 2.09) |

| RDCI, 0–7† | – | 0.93 (0.81, 1.08) | – | 0.98 (0.86, 1.11) |

| Pulmonary disease | – | 1.60 (0.72, 3.54) | – | 2.89 (1.28, 6.54) |

| Cardiovascular disease | – | 1.07 (0.47, 2.47) | – | 0.93 (0.44, 1.94) |

| Educational level, years | – | 1.06 (0.95, 1.19) | – | 0.97 (0.88, 1.07) |

| Medicare health insurance | – | 0.71 (0.43, 1.17) | – | 1.03 (0.67, 1.60) |

| PAS‐II, 0–10 | – | 0.98 (0.83, 1.15) | – | 1.10 (0.95, 1.27) |

| Number of prior DMARDs | – | 1.07 (0.96, 1.18) | – | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) |

| PSD scale | – | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | – | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) |

| Fatigue VAS, 0–10 | – | 1.11 (0.99, 1.24) | – | 1.01 (0.91, 1.11) |

Values are the odds ratio (95% confidence interval). bDMARDs = biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs; csDMARDs = conventional synthetic DMARDs; HCQ = hydroxychloroquine; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; NTNFi = non–tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; PAS‐II = Patient Activity Scale II; PSD = Polysymptomatic Distress; RDCI = Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index; Rheumatic VAS = visual analog scale.

The RDCI was calculated excluding pulmonary and cardiovascular disease, which were controlled individually.

When analyzing care changes, no association was found with any particular DMARD group in either model. Care changers were more likely to have pulmonary disease (OR 2.9 [95% CI 1.3, 6.5]), with a tendency for worse disease activity (OR 1.1 [95% CI 1.0, 1.1]) and GC use (OR 1.6 [95% CI 1.0, 2.5]).

Reasons for medication change

Participants were asked to report reasons why they stopped/delayed a drug or changed the dose. This question was not prompted when the change type was “added other drugs.” Reasons by change type and physician approval are presented in Table 4. Adding a new medication and changing the dose of a medication were changes significantly more likely to be directed by a physician (90% and 66%, respectively) compared to stopping/delaying a medication (53%) (P < 0.001).

Table 4.

Reasons for medication change by type of change and physician approval*

| Reason for medication change | Stopped/delayed medication | Changed medication dose | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All |

Not approved by physician |

Approved by physician |

P | All |

Not approved by physician |

Approved by physician |

P | |

| Total | 153 (100) | 68 (44.4) | 81 (52.9) | 68 (100) | 23 (33.8) | 45 (66.2) | ||

| Did not work | 13 (8.5) | 1 (1.5) | 12 (14.8) | 0.004 | 3 (4.4) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (4.4) | 0.985 |

| Side effects | 18 (11.8) | 4 (5.9) | 14 (17.3) | 0.033 | 6 (8.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (11.1) | 0.097 |

| Cost | 2 (1.3) | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.120 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Canceled/postponed appointments | 20 (13.1) | 16 (23.5) | 4 (4.9) | 0.001 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Not available | 5 (3.3) | 5 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.013 | 6 (8.8) | 2 (8.7) | 3 (6.7) | 0.762 |

| Worried about COVID‐19 | 60 (39.2) | 37 (54.4) | 20 (24.7) | 0.000 | 12 (17.6) | 6 (26.1) | 6 (13.3) | 0.192 |

| Other illness/infection | 24 (15.7) | 9 (13.2) | 15 (18.5) | 0.382 | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.4) | 0.305 |

| Loss of insurance | 3 (2.0) | 3 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.056 | 1 (1.45) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 0.471 |

| Having a disease flare | 4 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.9) | 0.063 | 28 (41.2) | 9 (39.1) | 19 (42.2) | 0.806 |

| Surgery/medical procedure | 8 (5.2) | 2 (2.9) | 6 (7.4) | 0.228 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Doctor recommended, unspecified reason | 3 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.7) | 0.109 | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.4) | 0.305 |

| No longer needed (e.g., disease flare over) | 7 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (8.6) | 0.013 | 6 (8.8) | 4 (17.4) | 2 (4.4) | 0.075 |

| Other | 14 (9.2) | 4 (5.9) | 9 (11.1) | 0.260 | 9 (13.2) | 2 (8.7) | 7 (15.6) | 0.430 |

Values are the number (%). Values reflect number of changes and not number of patients. Respondents could select more than one reason. Four patients did not indicate if their decision to stop medication was physician approved.

Of the six participants who reported a COVID‐19 diagnosis (four cases presumed by physician, one case confirmed by polymerase chain reaction [PCR] test, and one confirmed by antibody test), three had medication changes (two participants who were presumed COVID‐19–positive and one participant who was confirmed COVID‐19–positive by PCR test), and three did not have medication changes. Of those with medication changes, two respondents received physician approval and one did not.

The most commonly reported reason for stopping or delaying a drug was concern about COVID‐19 (39%), followed by concern about other illness or infections (16%), canceled/postponed appointments (13%), and side effects (12%). All other reasons for stopping or delaying a drug were reported by <10% of patients. For those who reported a change of dose, having a flare of disease activity was the most frequent reason (41%), followed by concern about COVID‐19 (17%) and other unspecified reasons (13%). Among individuals that stopped, delayed, or changed the dose of a medication, those who did so due to concern about COVID‐19 reported higher fatigue scores (mean ± SD 4.8 ± 2.7 versus 3.7 ± 2.8) (P = 0.02), but had no other significant differences in patient‐reported outcomes, comorbid conditions, or demographic characteristics (Supplementary Table 1, available on the Arthritis Care & Research website at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.24611/abstract). When looking at reasons by type of change and physician approval, efficacy, side effects, and no longer needing a medication were more likely to be directed by the physician as a reason for stopping/delaying a medication, as opposed to concern about COVID‐19, availability of the drug, or canceled/postponed appointments. For respondents who reported changing a medication dose, no significant differences were found between reasons for medication change, regardless of whether the change was physician‐directed or not.

Reasons for change were further inspected by change type within each drug class (Supplementary Table 2 [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.24611/abstract]). Worry about COVID‐19 was a constant reason and, in most of the cases, the most common reason for any medication change, irrespective of drug class. For HCQ users, lack of availability was the main reason for stopping/delaying the drug or changing dose. For respondents who used other csDMARDs, having a flare of disease activity was the main reason for adding other drugs to their treatment regimen. Worry about infections or other illness was also a frequent reason for stopping among TNFi and NTNF users, and in NTNF users, cancellation of appointments was also considered a significant reason for stopping or delaying the medication. Lastly, for respondents who received JAK inhibitors, canceled appointments and worry about COVID‐19 were the main reasons for stopping or delaying medication.

Time to medication change

Descriptive statistics for time to medication change by hierarchical DMARD group are shown (Table 5). Some respondents were excluded from this analysis because they did not report date of medication change (17% of changers had missing date of change). The probability of change ranged from 23% to 34%, and there was no significant difference between drug classes when selecting the highest DMARD level of each respondent. The probability of a respondent not experiencing any change in medication within 60 days of March 1, 2020 ranged from 76% to 84%, and within 90 days, ranged from 63% to 76%.

Table 5.

Survival descriptive statistics for the hierarchical DMARD groups*

|

Hierarchical DMARD drug class |

Time at risk (days) |

Probability of change | No subjects | Survival time | Probability of no change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25% | 50% | 60 days | 90 days | ||||

| No DMARDs | 3,635 | 0.38 | 55 | 61 | – | 0.76 | 0.59 |

| csDMARDs | 11,983 | 0.23 | 171 | – | – | 0.80 | 0.76 |

| TNFi† | 16,124 | 0.25 | 233 | 80 | – | 0.82 | 0.72 |

| NTNFi | 11,855 | 0.25 | 171 | 76 | – | 0.84 | 0.72 |

| JAK inhibitors | 43,80 | 0.34 | 66 | 61 | – | 0.76 | 0.63 |

csDMARDs = conventional synthetic biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs; NTNFi = non–tumor necrosis factor inhibitors.

P = 0.11 by log rank test.

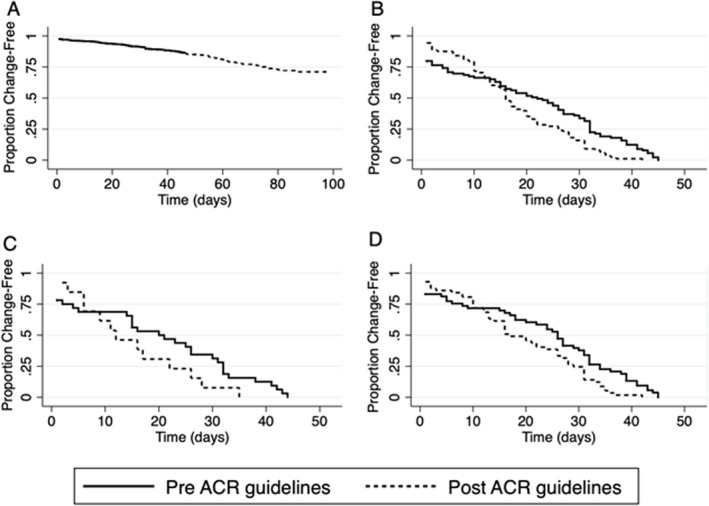

Finally, Kaplan‐Meier analysis was used to estimate the impact of the publication of the ACR guidance in April 2020 on medication use. Figure 1 shows overlaid curves for medications changers pre–ACR guidelines and post–ACR guidelines under a variety of conditions. The overall probability of changing medication was 26.3%, with an annual incidence rate (IR) of 1.39 (95% CI 1.21, 1.61). The number of changers was evenly distributed, with 93 patients overall experiencing a medication change prior to April 15 (IR = 1.15 [95% CI 0.93, 1.43]; probability of change 13.5%); among changers, the IR was 17.67 (95% CI 14.42, 21.66). Ninety patients overall made a medication change after April 15, with an IR of 1.74 (95% CI 1.41, 2.14) and a probability of change of 15.5%; among changers who changed medication after April 15, the IR was 21.02 (95% CI 17.10, 25.84). However, when restricted to only those patients who made a medication change in response to COVID‐19, most changes occurred prior to April 15, with 33 changes occurring prior to April 15 and 13 changes occurring after this date. While fewer COVID‐19–specific changes took place after April 15, the changes that were made after April 15 occurred more quickly (IR 18.60 [95% CI 13.22, 26.16] versus IR 24.60 [95% CI 14.29, 42.37] for changes made prior to April 15 and after April 15, respectively). The IRs for both physician‐approved and non–physician‐approved medication changes were higher after April 15 than prior to this date, with approximately equal sample sizes.

Figure 1.

Kaplan‐Meier curves showing time to medication change before and after April 15, 2020, the date the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidance for the management of rheumatic disease in adult patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic was published. Groups are categorized by reason for medication change and physician approval status, and all incidence rates per 100 patients are shown with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). A, Overall time to change beginning March 1, 2020 and ending at time of questionnaire completion, with 696 medication changes recorded in total. Of medication changes recorded in the pre‐ACR guidelines period, 696 occurred with an annual incidence rate of 1.16 (95% CI 0.94, 1.40). Of medication changes recorded in the post‐ACR guidelines period, 603 occurred with a 14.9% probability of change. B and C, Individuals who changed medications before and after the ACR guidance was published (B), and individuals who changed medications due to concern about COVID‐19 (C). D, Individuals who had medication changes that were approved by a physician. Incidence rate during the pre‐ACR guidelines period was 15.80 (95% CI 12.14, 20.59), with 55 medication changes recorded, and incidence rate during the post‐ACR guidelines period was 19.26 (95% CI 14.92, 24.86), with 59 medication changes recorded. In B–D, Panels are time to change before and after ACR guidelines were published, with curves overlaid. See Results for more data on incidence rates and medication changes among the patient groups.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that individuals with RA who had medication changes in the first three months of the COVID‐19 pandemic in the US were more likely to experience increased levels of disease activity and higher exposure to prior DMARDs, but no statistical difference was found in terms of comorbidities between individuals who changed medication in the first three months of the pandemic and those who did not. Patients who received bDMARDs and JAK inhibitors reported a higher incidence of medication discontinuation when compared to patients who received csDMARDs (16–18% versus <8%). For changes in care, switching to telehealth appointments was the most commonly reported change for patients who received NTNF bDMARDs and JAK inhibitors (42–46%), followed by cancelling or postponing appointments (28–35%), depending on the DMARD group. Of patients who received HCQ, 10% reported that they did not have access to the medication.

Almost all patients changed their behavior in response to the pandemic by washing their hands more often and wearing a mask or using hand sanitizer more often, independently of DMARD exposure. Other behavior changes (e.g., canceling travel) occurred less frequently but were still relevant. We found that substantially fewer individuals were restricting social contacts than reported by Favalli and colleagues in Lombardy, Italy, where 90% of patients with rheumatic diseases were following social distancing measures (16), although this may have been due to differences in the descriptors (self‐quarantine versus social distancing). Unlike prior US studies of the general population (17, 18), we found no significant differences in education level or health insurance status (Medicare versus other forms of health insurance) in adjusted models.

There were no significant differences in medication change frequency between DMARD groups. However, medication changers were three times more likely to be receiving GCs in addition to DMARDs. This may reflect efforts to reduce the perceived risk of infections due to GCs as well as the likely less controlled disease activity associated with GC use (19). The ACR recommendations acknowledged controversies in the available evidence for GC use and COVID‐19 risk, stating: “If indicated, glucocorticoids should be used at the lowest dose possible to control rheumatic disease, regardless of exposure or infection status. Glucocorticoids should not be abruptly stopped, regardless of exposure or infection status” (9). While this recommendation does not differ from the 2015 ACR guidelines for the treatment of RA (20), the majority of responding US rheumatologists purposefully reduced GC use during the early part of the US COVID‐19 pandemic (21). In addition, the majority of those individuals initiating GCs reported flares of disease activity (Supplementary Table 2, available on the Arthritis Care & Research website at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.24611/abstract), though the role the COVID‐19 pandemic may have had on these flares is unclear. Flares may have been the result of stress and lifestyle changes due to the pandemic, which warrants further investigation. It is beyond the scope of the current study to examine treatment for patients with COVID‐19, though some of the best evidence of treating people hospitalized for COVID‐19 infection involved GC use (22).

Since most disruptions in care should have affected all patients during the early weeks of the COVID‐19 pandemic due to massive changes in clinical care, we expected individuals with greater disease activity and medical utilization to be most impacted. Yet pulmonary disease seemed to be the strongest factor associated with changes in care (three‐fold increase in risk), followed by GC use. The results were robust regardless of changes in the way the drug variables were categorized, how models were selected, or how disease activity was captured. These findings may be more related to the perceived added risk of and/or increased COVID‐19 symptoms early in the pandemic (23). Both pulmonary disease and GC use are associated with mortality in RA (24), and recent studies find these variables similarly associated with COVID‐19 case mortality when RA activity was controlled (25).

Fear of COVID‐19 was the most commonly reported reason for medication changes, irrespective of drug class. Most changes related to dose or adding new medication were approved by physicians, but only half of changes related to discontinuation were physician‐approved. Half of patients worried about COVID‐19 stopped medications without physician approval. A snapshot survey of Australian patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases showed the greatest concern of COVID‐19 risk was with taking, in declining order, bDMARDs/targeted synthetic DMARDs (62%), csDMARDs (methotrexate; 55%), and GCs (38%) (7), which is consistent with our findings though the reported concerns of patients in the Australian cohort with csDMARD use were proportionally much higher than that subgroup of patients in the present study, as only half of the patients who received csDMARDs in the present study stopped medications compared to those who received treatment with bDMARDs/targeted synthetic DMARDs.

Some limitations of the present study include participation bias as patients more worried about COVID‐19 may have been more willing to participate in the study. In addition, this study required online responses, which excluded almost half of the current participants in the FORWARD registry who either complete mailed paper forms or telephone interviews. Participants who were unable to respond due to having COVID‐19 infection were left‐censored from our study, although this was likely a rare occurrence. While we did not find any association between race and education level with access to care or medications, the study participants were largely White and had a higher than average education level for the US. Also, due to timing of questionnaires, we did not have full medication information from participants after July 2019 because responses from the January 2020 standard questionnaire were not complete, and the 8‐month delay may have resulted in patients being misallocated to the DMARD treatment category if they had switched to another class during that time. Last, while the first ACR treatment recommendations during the pandemic are a convenient guidepost, it is possible that the changes observed were due to secular reasons, such as improved understanding of COVID‐19 or improved access to clinical care after the initial lockdowns across the US.

Though many items were measured during the early months of the US COVID‐19 pandemic, this study has provided important evidence of actual patient behavior in regard to changing treatments without physician recommendation due to fear of COVID‐19 risk that has only been theorized in editorials (26). While overall risks of contracting COVID‐19 in patients with RA are not known and important clinical trials of select RA DMARDs in the treatment of COVID‐19 have not concluded (4), there is evidence that GC use is associated with hospitalization for COVID‐19 (27). These results were published after the surveys were collected for the present study but are consistent with our findings as we also found statistically important associations between GC use and change in medications and care. Last, we also showed what was likely the importance of providing early recommendations to physicians on how best to treat patients with RA, as physician‐guided medication changes increased after the ACR guidance was first published.

In conclusion, we found that individuals with RA in the US had relatively high and consistent rates of medication changes through the first three months of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Physician approval for medication changes increased after publication of the ACR guidance for the management of rheumatic disease in adult patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic, and most medication changes made were due to concerns of COVID‐19 risk. We found no significant associations with medication changes and DMARD class. In full models, only GC use was associated with RA medication changes, and GC use and concomitant pulmonary disease were associated with changes in overall care. Further studies are needed to follow the trends in RA medication use in response to growing knowledge about the COVID‐19 pandemic and the impact of medications for both risk and treatment.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Michaud had full access to all the study data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design

Michaud, Wipfler, Agarwal, Katz.

Acquisition of data

Michaud, Wipfler.

Analysis and/or interpretation of data

Michaud, Pedro, Wipfler.

ROLE OF THE STUDY SPONSOR

Pfizer had no role in the study design or in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Publication of this article was not contingent upon approval by Pfizer.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the additional contributions by Rebecca Schumacher, Teresa Simon, and Drs. Yomei Shaw, Jacob Clarke, and Adam Cornish in the creation and implementation of the supplementary survey. As always, we could not have done this study without the many participants in FORWARD who continue to share their experiences during these challenging times.

Supported by Pfizer Inc.

Ms Agarwal owns stock or stock options in Pfizer Inc. No other disclosures relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1. Atzeni F, Masala IF, di Franco M , Sarzi‐Puttini P. Infections in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2017;29:323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hsu CY, Ko CH, Wang JL, Hsu TC, Lin CY. Comparing the burdens of opportunistic infections among patients with systemic rheumatic diseases: a nationally representative cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mehta B, Pedro S, Ozen G, Kalil A, Wolfe F, Mikuls T, et al. Serious infection risk in rheumatoid arthritis compared with non‐inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: a US national cohort study. RMD Open 2019;5:e000935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. NIH . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) treatment guidelines. URL: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov. [PubMed]

- 5. Ladani AP, Loganathan M, Danve A. Managing rheumatic diseases during COVID‐19. Clin Rheumatol 2020;39:3245–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, Tomashek KM, Wolfe CR, Ghazaryan V, et al. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with Covid‐19. N Engl J Med 2021;384:795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Antony A, Connelly K, De Silva T, Eades L, Tillett W, Ayoub S, et al. Perspectives of patients with rheumatic diseases in the early phase of COVID‐19. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020;72:1189–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Michaud K, Wipfler K, Shaw Y, Simon TA, Cornish A, England BR, et al. Experiences of patients with rheumatic diseases in the united states during early days of the COVID‐19 pandemic. ACR Open Rheumatol 2020;2:335–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mikuls TR, Johnson SR, Fraenkel L, Arasaratnam RJ, Baden LR, Bermas BL, et al. American College of Rheumatology guidance for the management of rheumatic disease in adult patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic: version 1. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72:1241–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kroon FP, Mikuls TR, Landewe RB. COVID‐19 and how evidence of a new disease evolves. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:401–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolfe F, Michaud K. The National Data Bank for rheumatic diseases: a multi‐registry rheumatic disease data bank. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Michaud K, Wolfe F. Comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2007;21:885–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wolfe F, Michaud K, Pincus T. Development and validation of the health assessment questionnaire II: a revised version of the health assessment questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:3296–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wolfe F, Michaud K, Pincus T. A composite disease activity scale for clinical practice, observational studies, and clinical trials: the patient activity scale (PAS/PAS‐II). J Rheumatol 2005;32:2410–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolfe F, Michaud K, Busch RE, Katz RS, Rasker JJ, Shahouri SH, et al. Polysymptomatic distress in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: understanding disproportionate response and its spectrum. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1465–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Favalli EG, Monti S, Ingegnoli F, Balduzzi S, Caporali R, Montecucco C. Incidence of COVID‐19 in patients with rheumatic diseases treated with targeted immunosuppressive drugs: what can we learn from observational data? Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72:1600–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weill JA, Stigler M, Deschenes O, Springborn MR. Social distancing responses to COVID‐19 emergency declarations strongly differentiated by income. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117:19658–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Andersen M. Early evidence on social distancing in response to COVID‐19 in the United States. SSRN Electronic Journal 2020. URL: 10.2139/ssrn.3569368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Caplan L, Wolfe F, Russell AS, Michaud K. Corticosteroid use in rheumatoid arthritis: prevalence, predictors, correlates, and outcomes. J Rheumatol 2007;34:696–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mehta B, Jannat‐Khah D, Mancuso CA, Bass AR, Moezinia CJ, Gibofsky A, et al. Geographical variations in COVID‐19 perceptions and patient management: a national survey of rheumatologists. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2020;50:1049–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. RECOVERY Collaborative Group , Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid‐19. N Engl J Med 2021;384:693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ahmed S, Gasparyan AY, Zimba O. Comorbidities in rheumatic diseases need special consideration during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Rheumatol Int 2021;41:243–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Listing J, Kekow J, Manger B, Burmester GR, Pattloch D, Zink A, et al. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: the impact of disease activity, treatment with glucocorticoids, TNFα inhibitors and rituximab. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:415–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Strangfeld A, Schäfer M, Gianfrancesco MA, Lawson‐Tovey S, Liew JW, Ljung L, et al. Factors associated with COVID‐19‐related death in people with rheumatic diseases: results from the COVID‐19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician‐reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:930–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pope JE. What Does the COVID‐19 pandemic mean for rheumatology patients? Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol 2020;6:71–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gianfrancesco M, Hyrich KL, Al‐Adely S, Carmona L, Danila MI, Gossec L, et al. Characteristics associated with hospitalisation for COVID‐19 in people with rheumatic disease: data from the COVID‐19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician‐reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:859–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material