Abstract

The most beneficial effect of corticosteroid therapy in COVID‐19 patients has been shown in subjects receiving invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), corresponding to a score of 6 on the World Health Organization (WHO) COVID‐19 Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement (OSCI). The aim of this observational, single‐center, prospective study was to assess the association between corticosteroids and hospital mortality in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) patients who did not receive IMV (OSCI 3–5). Included were 1,311 COVID‐19 patients admitted to nonintensive care wards, and they were divided in two cohorts: (i) 480 patients who received corticosteroid therapy and (ii) 831 patients who did not. The median daily dose was of 8 mg of dexamethasone or equivalent, with a mean therapy duration of 5 (3–9) days. The indication to administer or withhold corticosteroids was given by the treating physician. In‐hospital mortality was similar between the two cohorts after adjusting for possible confounders (adjusted odds ratio (ORadj) 1.04, 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.81–1.34, P = 0.74). There was also no difference in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission (ORadj 0.81, 95% CI, 0.56–1.17, P = 0.26). COVID‐19 patients with noninvasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) had a lower risk for ICU admission if they received steroid therapy (ORadj 0.58, 95% CI, 0.35–0.94, P = 0.03). In conclusion, corticosteroids were overall not associated with a difference in hospital mortality for patients with COVID‐19 with OSCI 3–5. In the subgroup of patients with NIMV (OSCI 5), corticosteroids reduced ICU admission, whereas the effect on mortality requires further studies.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

☑ The efficacy of corticosteroids in the treatment of patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) and oxygen therapy has been demonstrated in randomized clinical trials and their meta‐analyses.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

☑ What is the association between treatment with corticosteroids and in‐hospital mortality in noncritically ill COVID‐19 patients who did not receive invasive mechanical ventilation?

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD TO OUR KNOWLEDGE?

☑ Differently from mechanically ventilated COVID‐19 patients, there is no association between corticosteroids and mortality in COVID‐19 patients who did not receive IMV.

HOW MIGHT THIS CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE?

☑ This study shows that corticosteroid therapy is not useful in COVID‐19 patients not receiving IMV. Of note, our data is conflicting with results from the RECOVERY trial, and therefore gathering more evidence on the subject would be desirable.

In the past months, the spotlight has been on the effects of corticosteroid therapy on hospitalized patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), with many randomized clinical trials being conducted on the subject. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5

Many of the ongoing trials were stopped early, due to the results of the preliminary report from the RECOVERY Collaborative Group, which showed that the use of dexamethasone was associated with a lower 28‐day mortality in patients who were receiving either invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation or oxygen therapy, compared with standard care. 5

While the evidence in favor of corticosteroid therapy in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) from any cause 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 seems to be confirmed also in ARDS secondary to COVID‐19, the RECOVERY Collaborative Group Preliminary Report results were consistent with dexamethasone being possibly harmful in patients not receiving oxygen therapy. 5

The aim of this study was to assess the association between corticosteroid therapy and hospital mortality in noncritically ill COVID‐19 patients, who had been admitted to the ward for more than 24 hours and who did not need invasive mechanical ventilation (with a score of 3, 4, and 5 on the World Health Organization (WHO) COVID‐19 Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement (OSCI)).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

In this observational cohort study, data were prospectively collected from the electronic medical records of patients admitted between February 20 and May 10, 2020 to Poliambulanza Foundation Hospital, a 600‐bed tertiary care hospital in Northern Italy. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Brescia.

Patients were included in the study if they had a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2)–positive reverse transcriptase real‐time polymerase chain reaction test on biological material obtained from a nasopharyngeal swab, if they had been admitted to a nonintensive ward, and if they did not receive invasive mechanical ventilation at the time of enrollment. Patients with a score of 3, 4, and 5 on the WHO COVID‐19 OSCI were included: 10 Patients with a score of 3 were hospitalized patients not receiving oxygen therapy, patients with a score of 4 were hospitalized patients receiving oxygen by mask or nasal prongs, and patients with a score of 5 were patients receiving noninvasive positive pressure ventilation or high‐flow oxygen.

Patients were excluded if they were younger than 18 years, had been admitted directly to the intensive care unit (ICU), or had a length of stay on the ward of < 24 hours. Oxygen therapy was started if oxygen saturation was < 90%; noninvasive mechanical ventilation was indicated in the presence of dyspnea or with oxygen saturation < 90% despite oxygen therapy. ICU admission and invasive mechanical ventilation were indicated if, despite noninvasive ventilation, any of the following were present: ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) < 100 mmHg, dyspnea, respiratory rate > 40 breaths per minute, or tidal volume > 10 ml/kg.

Patients were divided into two cohorts: (i) patients who received corticosteroid therapy on the ward and (ii) patients who did not receive corticosteroid therapy on the ward.

Corticosteroid therapy with drugs different from dexamethasone was converted to the equivalent dose. 11 The choice of patients’ treatment plan and the decision to start or withhold corticosteroid therapy was made by the attending physician, since there was no clear evidence in favor or against the use of corticosteroids in COVID‐19 patients at the time of the study.

Primary outcome was association between corticosteroid use and in‐hospital mortality. The association between corticosteroid therapy and ICU admission was the secondary outcome.

For secondary analyses, patients were divided according to the need of positive pressure support: The noninvasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) group included all patients with a score of 5 on the WHO COVID‐19 OSCI, that is to say patients that received noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (continuous positive airway pressure or pressure support ventilation), while the group of patients not on NIMV included all patients with a score of 3 or 4 on the WHO COVID‐19 OSCI, i.e., patients that did not receive positive pressure ventilation (spontaneously breathing patients, with or without oxygen therapy).

Statistical analysis

One thousand fifty four patients were needed to obtain a power of 80% to detect an odds ratio of 0.7, assuming mortality was 25% in those receiving corticosteroids, with one patient treated with corticosteroids for every three patients admitted to the hospital and alpha error = 0.05.

Continuous variables are expressed with mean (standard deviation, SD) or median (1° quartile–3° quartile) as appropriate, discrete variable as count (percentage). Bivariate analysis of the outcome was performed with Fisher's exact test for factorial variables and Student’s t‐test for continuous ones. Association with corticosteroid treatment was assessed, and a propensity score was estimated using variables that were associated with treatment allocation and survival. The overlap weight method was used for balancing variables between the corticosteroids cohort and control cohort. 12 Association with hospital survival was assessed with logistic regression; odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) are reported. A second analysis was conducted with proportional hazard ratios. Patients were considered alive after hospital discharge and the results were reported in explicative figures.

Collinearity was assessed with variation inflation factor, and variables were excluded from the multivariate model if variation inflation factor was > 3 and if there was correlation with other explanatory variables (for example, PaO2/FiO2 and PaO2). Missing values, in covariates, were assessed and replaced with mean substitution. A sensitivity analysis including only complete cases was conducted to evaluate the effect of missing values.

Planned secondary analyses were conducted according to the daily dosage of corticosteroids used: more than 8 mg of dexamethasone/die (the median daily dose) and less than or equal to 8 mg/die, and assessing the effect of corticosteroids in patients with or without noninvasive ventilation.

Statistical analysis was performed using R Studio software version 4.0.0 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria, 2014) and packages "psw" and "survival" for overlap weight propensity score and Cox’s model estimation, respectively.

RESULTS

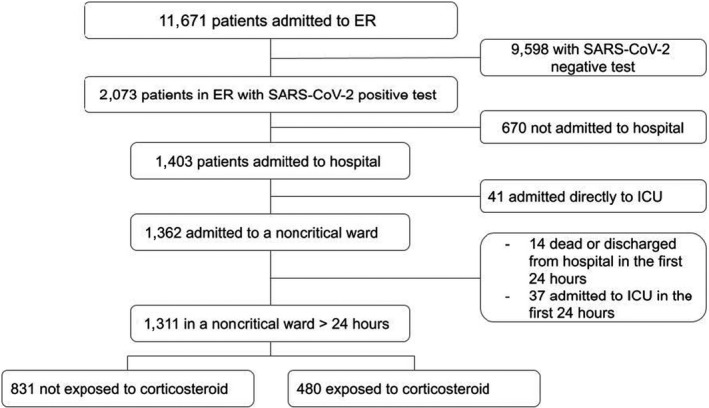

As shown in Figure 1 , 11,671 patients visited Fondazione Poliambulanza’s emergency room during the study period, 2,053 of them tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2, and 1,403 of those were admitted to the hospital. Forty‐one of them were admitted directly to the ICU, while 1,362 were admitted to a nonintensive ward. In the first 24 hours of hospital stay, 37 patients went to intensive care, and 14 died or were discharged: They were therefore excluded from analyses. Of the 1,311 remaining patients, 480 were exposed to steroids, and 831 were not (Figure 1 ). Three hundred ninety patients underwent noninvasive mechanical ventilation on the nonintensive care wards; 203 of them received corticosteroid therapy and 187 did not.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study patients. ER, emergency room; ICU, intensive care unit; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

The median daily equivalent dose of dexamethasone was 8 (4–17) mg per day.

Duration of corticosteroid therapy was 5 (3–9) days, and corticosteroid therapy was started on day 2 (2–5) of the hospital stay.

Characteristics of patients in the corticosteroid and in the no corticosteroid cohorts are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| No corticosteroids | Corticosteroids | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | N (%) | 831 (63) | 480 (37) | |

| Age | years | 69 (15) | 69 (12) | 0.29 |

| Body mass index | kg/m2 | 26.3 (5.0) | 26.9 (4.4) | 0.050 |

| Female sex | N (%) | 282 (34) | 175 (37) | 0.39 |

| Arterial hypertension | N (%) | 280 (34) | 209 (44) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | N (%) | 165 (20) | 117 (24) | 0.064 |

| PaO2 | mmHg | 59.3 (22.0) | 53.0 (16.0) | < 0.001 |

| pH | 7.47 (0.6) | 7.49 (0.5) | < 0.001 | |

| PaCO2 | mmHg | 34.7 (6.6) | 34.0 (7.0) | 0.049 |

| PaO2/FIO2 | mmHg | 272 (73) | 244 (69) | < 0.001 |

| HCO3 ‐ | mmol/L | 24.6 (3.8) | 24.9 (3.5) | 0.29 |

| Lactate | mmol/L | 1.3 (1.1) | 1.3 (0.9) | 0.97 |

| Leukocytes | 109/L | 7.9 (4.1) | 8.4 (4.3) | 0.04 |

| Lymphocytes | 109/L | 1.2 (1.3) | 1.0 (0.7) | 0.005 |

| Platelets | 109/L | 194.3 (91.0) | 204.3 (95.8) | 0.07 |

| C‐reactive protein | mg/dL | 98.0 (79.3) | 129.8 (89.6) | < 0.001 |

| Lactic dehydrogenase | U/L | 427.7 (240.6) | 501.0 (184.7) | 0.20 |

| Bilirubin | mg/dL | 0.8 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.5) | 0.15 |

| Treated with enoxaparin | N (%) | 359 (43) | 364 (76) | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation) or as count (percentage).

FIO2, fractional inspired oxygen; HCO3 ‐, bicarbonate; ICU, intensive care unit; PaCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2, arterial oxygen partial pressure.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of survivors and nonsurvivors, with nonsurvivors being older, more frequently male, with a higher incidence of diabetes mellitus and a more severe respiratory dysfunction at baseline.

Table 2.

Characteristics of survivors and nonsurvivors

| Alive | Dead | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | N (%) | 1,006 (76) | 305 (24) | |

| Age | years | 66 (14) | 78 (9) | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index | kg/m2 | 26.4 (4.7) | 26.7 (5.2) | 0.41 |

| Female sex | N (%) | 362 (37) | 83 (27) | 0.003 |

| Arterial hypertension | N (%) | 370 (37.6) | 119 (39.1) | 0.67 |

| Diabetes | N (%) | 200 (20.3) | 82 (27.0) | 0.017 |

| PaO2 | mmHg | 59.1 (19.1) | 50.2 (21.6) | < 0.001 |

| PaCO2 | mmHg | 34.8 (6.5) | 33.4 (7.1) | 0.003 |

| PaO2/FIO2 | mmHg | 275.1 (66.1) | 217.2 (73.9) | < 0.001 |

| pH | 7.48 (0.5) | 7.47 (0.6) | 0.001 | |

| HCO3 ‐ | mmol/L | 25.1 (3.4) | 23.5 (4.4) | < 0.001 |

| Lactate | mmol/L | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.7 (1.5) | < 0.001 |

| Leukocytes | 109/L | 7.9 (3.7) | 8.6 (5.4) | 0.009 |

| Lymphocytes | 109/L | 1.2 (1.0) | 0.9 (1.2) | 0.002 |

| Platelets | 109/L | 204.6 (91.4) | 175.3 (88.1) | < 0.001 |

| C‐reactive protein | mg/L | 97.9 (80.1) | 149.2 (87.9) | < 0.001 |

| Lactic dehydrogenase | U/L | 432.9 (178.6) | 611.7 (306.9) | 0.016 |

| Bilirubin | mg/dL | 0.8 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.6) | 0.13 |

| Treated with enoxaparin | N (%) | 544 (55) | 165 (54) | 0.82 |

| Treated with corticosteroid | N (%) | 350 (36) | 125 (41) | 0.09 |

| Outcome: ICU admission | N (%) | 42 (4) | 59 (19) | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation) or as count (percentage).

FIO2, fractional inspired oxygen; , bicarbonate; ICU, intensive care unit; PaCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2, arterial oxygen partial pressure.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

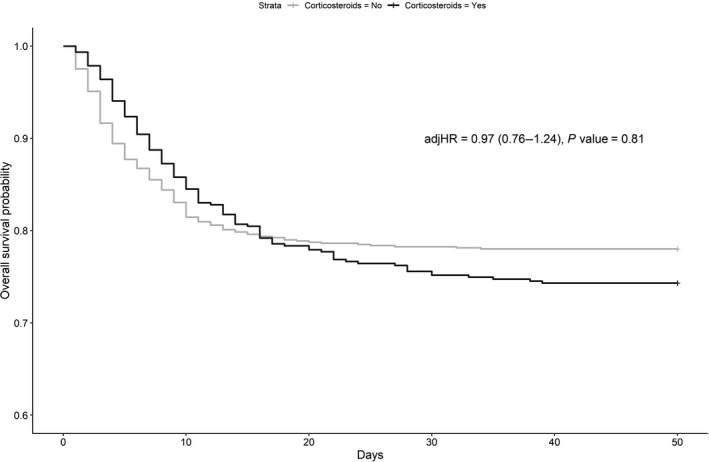

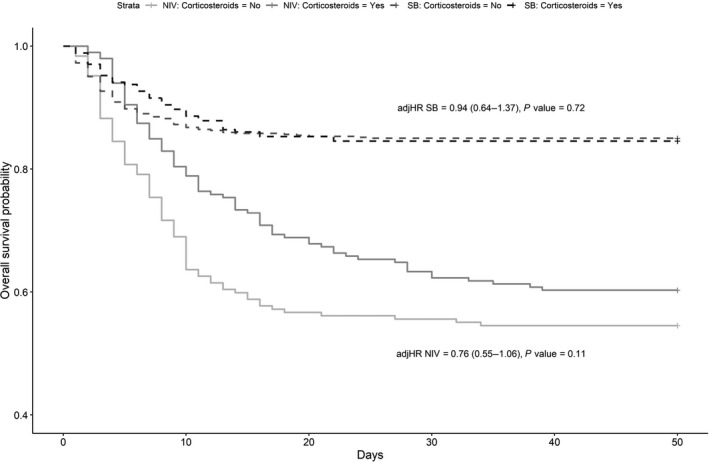

Table 3 shows that the OR for in‐hospital mortality is not statistically different between the cohort of patients receiving and the one not receiving corticosteroids (adjusted odds ratio (ORadj) 1.04, 95% CI, 0.81–1.34, P = 0.74) after adjusting for possible confounders. This finding was confirmed by the survival analysis (Figure 2 ). There is also no difference for the secondary outcome of ICU admission (ORadj 0.81, 95% CI, 0.56–1.17, P = 0.26). In the planned subgroup analysis, corticosteroid therapy was not found to increase survival in patients with a score of 3 and 4 on the WHO COVID‐19 OSCI (ORadj 0.95, 95% CI, 0.66–1.35, P = 0.78) nor in patients with a score of 5 on the WHO COVID‐19 OSCI (ORadj 0.79, 95% CI, 0.53–1.17, P = 0.24) (Figure 3 ). Patients on noninvasive mechanical ventilation (score of 5 on the WHO COVID‐19 OSCI) who received corticosteroids were less likely to be admitted to the ICU (ORadj 0.58, 95% CI, 0.35–0.94, P = 0.03).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratio

| Outcome | No corticosteroids (number/total (%)) | Corticosteroids (number/total (%)) | Estimate (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In‐hospital death | 179/831 (22) | 125/480 (26) | 1.04 (0.81–1.34) | 0.74 |

| In‐hospital death in NIMV patients | 85/187 (45) | 83/203 (41) | 0.79 (0.53–1.17) | 0.24 |

| In‐hospital death in patients not receiving NIMV (with/without oxygen) | 94/644 (15) | 42/277 (15) | 0.95 (0.66–1.35) | 0.78 |

| ICU admission | 56/831 (7) | 53/480 (11) | 0.81 (0.56–1.17) | 0.26 |

| ICU admission in NIMV patients | 38/187 (20 ) | 41/203 (20) | 0.58 (0.35–0.94) | 0.03 |

| ICU admission in patients not receiving NIMV (with/without oxygen) | 18/644 (3) | 18/277 (6) | 0.88 (0.45–1.70) | 0.71 |

Patients on NIMV are patients with a score of 5 on the WHO COVID‐19 Ordinal Scale For Clinical Improvement; patients not receiving NIMV are patients with a score of 3 and 4 on the WHO COVID‐19 Ordinal Scale For Clinical Improvement.

CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; NIMV, noninvasive mechanical ventilation.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Figure 2.

Overall survival probability in patients not receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, both treated and not treated with corticosteroids. adjHR, adjusted hazard ratio.

Figure 3.

Overall survival probability in patients receiving or not receiving noninvasive mechanical ventilation, both treated and not treated with corticosteroids. adjHR, adjusted hazard ratio; NIMV, patients with a score of 5 on the WHO COVID‐19 Ordinal Scale For Clinical Improvement; SB, patients with a score of 3 and 4 on the WHO COVID‐19 Ordinal Scale For Clinical Improvement; WHO, World Health Organization.

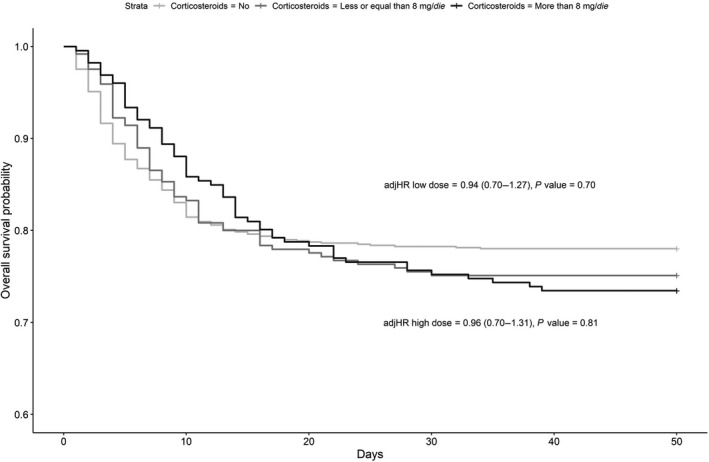

Figure 4 shows the overall survival probability in patients not needing invasive mechanical ventilation, treated with more than 8 mg of dexamethasone/die and less than or equal to 8 mg/die, or not treated with corticosteroids; no difference in mortality was found in either cohort.

Figure 4.

Overall survival probability in patients not receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, treated with high or low equivalent dose of dexamethasone or not treated with corticosteroids. adjHR, adjusted hazard ratio.

Analyses of completed cases were in agreement with what has been reported with substitution of missing values by the mean.

DISCUSSION

Our findings show that corticosteroid therapy is not associated with any difference in hospital mortality for patients with COVID‐19 who score 3, 4, or 5 on the WHO COVID‐19 OSCI, i.e., not receiving invasive mechanical ventilation.

At the beginning of the COVID‐19 pandemic, caution was advised when prescribing corticosteroids, due to the possibility of a more prolonged viral shedding and delayed viral clearance, 13 which was also shown for other similar viral infections, like Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome. 14 Many guidelines did not recommend the use of corticosteroids in COVID‐19 patients, 15 and the World Health Organization initially discouraged corticosteroid use in COVID‐19 due to the absence of any survival benefit and the possibility of harmful effects (avascular necrosis, psychosis, or diabetes) found in patients with SARS. 16

In the following months, evidence specific to SARS‐CoV‐2 emerged from randomized clinical trials, showing the benefit of corticosteroid treatment on critically ill COVID‐19 patients with severe forms of the disease. 1 , 4 , 5 These patients underwent invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation for severe hypoxemia in a disease characterized by diffuse viral pneumonia, suggesting that most of them could be classified as patients with moderate to severe ARDS. Therefore the results of clinical trials on the use of steroids in severe COVID‐19 appear to be in agreement with current treatment guidelines for ARDS patients, like the ones produced by the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) in 2017, which recommend the use corticosteroids in patients with early moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. 17 Moreover, a recent study by Villar et al. found that early administration of dexamethasone could reduce duration of mechanical ventilation and overall mortality in patients with established moderate to severe ARDS. 7 The benefit of corticosteroid treatment in patients with ARDS could be due to their effect on the inflammatory state that is a hallmark of the disease, 18 since corticosteroids affect numerous steps in the inflammatory pathway. 19

In patients who are not critically ill, the evidence is less compelling. In community acquired pneumonia, dexamethasone could reduce length of hospital stay when added to antibiotic treatment in nonimmunocompromised patients, 20 and it could reduce mortality and the need for mechanical ventilation. 21 But evidence in influenza, another viral disease that can cause severe respiratory symptoms, shows that corticosteroid treatment is associated with increased mortality and hospital‐acquired superinfection. 22 In COVID‐19, data from the RECOVERY Collaborative Group Preliminary Report showed no benefit (and the possibility of harm) among patients who did not receive oxygen therapy. 5 Our data suggest that corticosteroids are not beneficial in patients without invasive mechanical ventilation (with a score of 3,4, or 5 on the WHO COVID‐19 OSCI 10 ). In particular, this appears to be evident in all patients with a score of 3 or 4, i.e., patients with or without oxygen therapy who are not on positive pressure noninvasive ventilation. Since ARDS diagnostic criteria include the use of at least 5 centimeters of water of end‐expiratory pressure, patients receiving oxygen therapy but not on NIMV / continuous positive airway pressure and patients not receiving oxygen cannot have an ARDS diagnosis. 23

Differently from previous trials on corticosteroids in COVID‐19 patients, 1 , 2 , 3 , 5 we assessed patients who received noninvasive ventilatory support (with a score of 5 on the WHO COVID‐19 OSCI) as a separate group from patients who score 3 or 4 on the same scale. With this stratification of study sample, corticosteroids showed a protective effect against the need for ICU admission for patients with a score of 5 on the WHO scale (i.e., noninvasively mechanical ventilated patients). Differently from the RECOVERY trial, 5 we did not find any mortality reduction in patients receiving steroid therapy. This could depend on the exclusion of patients with a score of 6 on the WHO COVID‐19 scale of clinical improvement (invasive mechanical ventilation patients), which were the stratum with the most benefit in survival with steroids. The secondary analysis on patients with score of 3, 4, and 5 is not comparable with the one in the RECOVERY trial, because we aimed to assess the effect of steroids in ventilated (score of 5) versus nonventilated (with a score of 3 and 4) patients, whereas RECOVERY separately analyzed patients without oxygen therapy (with a score of 3) separately from patients with oxygen therapy (with a score of 4 and 5). The subgroup analysis in patients without mechanical ventilation (score of 3 and 4) clearly confirms the absence of effect of steroids on mortality, confirming the primary analysis. The effect of steroids on survival is more complex to interpret in patients on NIMV (with a score of 5), because a trend toward the improvement could be detected and the sample size of the NIMV patients (390 patients) gives a low statistical power (beta = 0.553). In absence of further evidence on COVID‐19 patients with noninvasive mechanical ventilation, we think that steroid use should be suggested in these patients because it reduces ICU admission and it can possibly have an effect on mortality reduction. It should be noted that COVID‐19 requiring noninvasive mechanical ventilation probably met all moderate to severe ARDS diagnostic criteria (acute onset, PaO2/FIO2 lower than 200, bilateral lung infiltrates, and absence of cardiogenic origin of respiratory failure). 23 Therefore our data show once more how corticosteroid efficacy seems to be linked to the more severe disease stages of COVID‐19. Since corticosteroid treatment is not exempt from side effects, and has been associated with complications such as increased infection rate, 24 hyperglycemia, 20 , 25 hypernatremia, 26 and ICU‐acquired weakness, 27 we think that caution should be exercised when prescribing corticosteroids to COVID‐19 patients who are not receiving ventilatory support.

Recent data showed that a high dose of corticosteroids, defined as higher than 1 mg/kg/day of prednisone (equivalent to 10 mg of dexamethasone a day in a 70‐kg patient), 11 was independently associated with an increased risk of death in patients with severe COVID‐19. 28 When conducting the planned secondary analysis dividing patients receiving higher or lower equivalent dexamethasone doses, no difference in mortality was found in our cohorts. A post hoc analysis was conducted, with a cutoff of 6 mg of daily dexamethasone or less (the RECOVERY trial cutoff), which did not show any difference between strata (see Supplemental Material ). Nevertheless there appears to be a trend towards a better outcome (as compared with the higher doses) in patients treated with 6 mg of dexamethasone daily dexamethasone or less, but the study was underpowered to detect this difference. Simulating from the data that were collected during the present study to obtain a power of 0.8 with type I error rate set at 0.05, and assuming that 1 of every 2 patients will be exposed to corticosteroids in low dose, i.e., 6 mg of daily dexamethasone or less, a total of 2,339 patients would need to be enrolled to detect an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.75.

The effect of corticosteroids on outcome was adjusted for the possible associated treatment with enoxaparin, which has been shown to be associated with a reduction in mortality risk in COVID‐19 patients. 29

We believe that our findings could be generalized to other patients with severe COVID‐19, because our patients’ characteristics and outcomes are comparable to what was found in other studies. 1 , 2 , 3 , 5 Nevertheless, our study suffers from four main limitations: First, it is an observational prospective analysis of prospectively collected data; therefore the absence of randomization makes it impossible to exclude the presence of bias or unmeasured confounders. Second, it is a single‐center study, so our results might not be valid for centers with different settings. Patients we have enrolled are patients with a score of 3, 4, and 5 on the WHO COVID‐19 OSCI; therefore caution is advised when applying these findings to patients with a different disease severity. Nonetheless, even if multicenter randomized clinical trials (RCTs) are the gold standard in assessing a treatment’s efficacy and safety, observational studies, which usually have a greater external validity than RCTs, can add information on the use of certain drugs in the clinical field and should be integrated with RCTs. Third, corticosteroid therapy was administered as per treating physicians’ decision and without prespecified criteria. Fourth, in this cohort of patients, the mean duration of steroid therapy, which is of 5 (3–9) days, is shorter than the one proposed in the RECOVERY trial protocol, in which dexamethasone was prescribed for 10 days or until hospital discharge. This difference could hypothetically explain a discrepancy in hospital mortality, nevertheless the effective duration of steroid therapy in the RECOVERY trial was 7 days (interquartile range 3 to 10) and the possibility that just 2 more days of steroid therapy could explain these different findings is remote. A subgroup analysis for corticosteroid therapy duration was not feasible because it would inevitably lead to immortal patient bias, 30 by selecting patients who survived for more than 7 days in the steroids group, thus leading to a biased association with reduced mortality.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, data from our observational, prospective, single‐center study show that treatment with corticosteroids is not associated with in‐hospital mortality reduction in patients admitted for COVID‐19 who did not receive invasive mechanical ventilation. In the subgroup of COVID‐19 patients treated with noninvasive mechanical ventilation, corticosteroid therapy is associated with a lower OR for ICU admission, whereas the effect on mortality has to be addressed in further studies.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no competing interests for this work.

Author contributions

G.N., F.F., and F.A. wrote the manuscript. G.N., F.A., and F.F. designed the research. All the authors performed the research. F.A. and G.N. analyzed the data.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Tomazini, B.M. et al. Effect of dexamethasone on days alive and ventilator‐free in patients with moderate or severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and COVID‐19: the CoDEX randomized clinical trial. JAMA 324, 1307–1316 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dequin, P.‐F. et al. Effect of hydrocortisone on 21‐day mortality or respiratory support among critically ill patients with COVID‐19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 324, 1298–1306 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Writing Committee for the REMAP‐CAP Investigators et al. Effect of hydrocortisone on mortality and organ support in patients with severe COVID‐19: the REMAP‐CAP COVID‐19 corticosteroid domain randomized clinical trial. JAMA 324, 1317–1329 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID‐19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID‐19: a meta‐analysis. JAMA 324, 1330–1341 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. The RECOVERY Collaborative Group . Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid‐19. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 693–704 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abdelsalam Rezk, N. & Mohamed Ibrahim, A. Effects of methyl prednisolone in early ARDS. Egypt. J. Chest Dis. Tuberc. 62, 167–172 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Villar, J. et al. Dexamethasone treatment for the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 267–276 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meduri, G.U. et al. Methylprednisolone infusion in early severe ARDS: results of a randomized controlled trial. Chest 131, 954–963 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meduri, G.U. et al. Effect of prolonged methylprednisolone therapy in unresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 280, 159–165 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. The World Health Organization . COVID‐19 therapeutic trial synopsis <https://www.who.int/blueprint/priority‐diseases/key‐action/COVID‐19_Treatment_Trial_Design_Master_Protocol_synopsis_Final_18022020.pdf> (2020). Accessed February 18, 2020.

- 11. Schimmer, B. & Funder, J.W. ACTH, adrenal steroids, and pharmacology of the adrenal cortex. In Goodman & Gilman's: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 1209–1235 (McGraw‐Hill Education, New York, NY, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li, F. , Morgan, K.L. & Zaslavsky, A.M. Balancing covariates via propensity score weighting. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 113, 390–400 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ling, Y. et al. Persistence and clearance of viral RNA in 2019 novel coronavirus disease rehabilitation patients. Chin. Med. J. 133, 1039–1043 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arabi, Y.M. et al. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 197, 757–767 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dagens, A. et al. Scope, quality, and inclusivity of clinical guidelines produced early in the covid‐19 pandemic: rapid review. BMJ 369: m1936 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization . Interim guidance: clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID‐19 disease is suspected <https://www.who.int/docs/default‐source/coronaviruse/clinical‐management‐of‐novel‐cov.pdf> (2020). Accessed March 13, 2020.

- 17. Annane, D. et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of critical illness‐related corticosteroid insufficiency (CIRCI) in critically ill patients (part I): Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) 2017. Crit. Care Med. 45, 2078–2088 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meduri, G.U. The role of the host defence response in the progression and outcome of ARDS: pathophysiological correlations and response to glucocorticoid treatment. Eur. Respir. J. 9, 2650–2670 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williams, D.M. Clinical pharmacology of corticosteroids. Respir. Care 63, 655–670 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meijvis, S.C.A. et al. Dexamethasone and length of hospital stay in patients with community‐acquired pneumonia: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet 377, 2023–2030 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Siemieniuk, R.A.C. et al. Corticosteroid therapy for patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 163, 519–528 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lansbury, L.E. , Rodrigo, C. , Leonardi‐Bee, J. , Nguyen‐Van‐Tam, J. & Shen Lim, W. Corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of influenza: an updated cochrane systematic review and meta‐analysis. Crit. Care Med. 48, e98–e106 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. ARDS Definition Task Force . Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA 307, 2526–2533 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Giacobbe, D.R. et al. Bloodstream infections in critically ill patients with COVID‐19. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 50, e13319 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weber‐Carstens, S. et al. Impact of bolus application of low‐dose hydrocortisone on glycemic control in septic shock patients. Intensive Care Med. 33, 730–733 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fang, F. et al. Association of corticosteroid treatment with outcomes in adult patients with sepsis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 179, 213–223 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang, T. , Li, Z. , Jiang, L. & Xi, X. Corticosteroid use and intensive care unit‐acquired weakness: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Crit. Care 22, 187 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li, X. et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID‐19 inpatients in Wuhan. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 146, 110–118 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Albani, F. et al. Thromboprophylaxis with enoxaparin is associated with a lower death rate in patients hospitalized with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. A cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 27, 100562 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lévesque, L.E. , Hanley, J.A. , Kezouh, A. & Suissa, S. Problem of immortal time bias in cohort studies: example using statins for preventing progression of diabetes. BMJ 340, b5087 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material