Abstract

Problem

Suicide incidences among adolescents and youths during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) lockdowns have been reported across the world. However, no studies have been carried out to investigate cumulative nature, patterns, and causative factors of such suicide incidences.

Methods

A purposive sampling of Google news between 15 February and 6 July was performed. After excluding duplicate reports, the final list comprised a total of 37‐suicide cases across 11 countries.

Findings

More male suicides were reported (21‐cases, i.e., 56.76%), and the mean age of the total victims was 16.6 ± 2.7 years (out of a total of 29 cases). About two‐thirds of the suicides were from three countries named India (11‐cases), UK (8‐cases), and the USA (6‐cases). Out of 23‐student victims, 14 were school‐going students. Hanging was the most common suicide method accounting in 51.4% of cases. The most common suicide causalities were related to mental sufferings such as depression, loneliness, psychological distress, and so forth, whereas either online schooling or overwhelming academic distress was placed as the second most suicide stressors followed by TikTok addiction‐related psychological distress, and tested with the COVID‐19.

Conclusions

The finding of the temporal distribution of suicides concerning lockdowns may help in exploring and evolving public measures to prevent/decrease pandemic‐related suicides in young people.

Keywords: adolescent suicide, COVID‐19 self‐harm, COVID‐19 suicide, press reporting suicide, teenage suicide, youth suicide

1. INTRODUCTION

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19), since its start and following massive global transmission spread has shaped several challenges for the healthcare workers and the general people across the world (Jahan et al., 2021; Mamun, Bodrud‐Doza, et al., 2020). The pandemic is expected to lead to a substantial degree of mental health crisis along with other aspects of the quality of life (Hossain et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2020; Pedrosa et al., 2020). Hence, the World Health Organization (2020) has issued brief messages related to psychological and mental health considerations and has emphasized the execution of psychological first aid. The publics' mounting concern about the spread of infection from the alleged/suspected COVID‐19 positive individuals has twisted a psychological panic mode in the society, although this may be advocated for suppressing the infection rate (World Health Organization, 2020). However, this has also led to a substantial increase in anxiety or fear of COVID‐19, whereas extreme fear and worry aggravates psychological instabilities (Pedrosa et al., 2020). As a consequence, suicide occurrences are being reported because of COVID‐19‐related fear (Dsouza et al., 2020; Mamun & Griffiths, 2020a)

Globally suicide death rate is increasing day‐by‐day; for instance, a 30% increment is observed in the United States between 2000 and 2016 (Miron et al., 2019). As reported by the World Health Organization (2014), nearly 800,000 people commit suicide every year throughout the entire world, which was projected to be nearly 1.5 million by the year 2020; and of the total suicides, about 80% occur in the low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) (Bilsen, 2018). The same report also claimed, suicide as the second most leading cause of mortality after the unintentional injury‐related deaths among the age groups of 15–19 years (World Health Organization, 2014). The suicide incidence rates in the younger age group are higher than the kids' (i.e., 15.3 and 11.2 per 100,000 and 0.9 and 1.0 per 100,000 among males and females respectively for the 15–29 years and 5–14 years older, respectively; Bilsen, 2018). In the United States, adolescents aged between 15 and 19 years, there were no significant suicide incidence changes within 2000–2007 (i.e., 8 per 100,000 people), although a 3.1% and 10.0% increment rate is observed in the years of 2014 and 2017, respectively (Miron et al., 2019). There are a few possible factors that signify the suicide rate among adolescents and youths compared with other age groups, particularly an increase in relationship problems, educational distress, social media use, depression, anxiety, trauma, and so forth (Bilsen, 2018; Miron et al., 2019).

Traumatic events like the current COVID‐19 pandemic, undoubtedly affect all demographics including children and adolescents. The common behavioral and emotional changes such as—(i) sleep problems and nightmares, (ii) development of unfounded fears, (iii) increase drugs, alcohol, or tobacco use, (iv) become isolated from others, (v) lose interest in funny activities, (vi) be angry or resentful easily, (vii) be disruptive or disrespectful or behave destructively, and so forth, are prevalent (Erbacher, 2020; National Institute of Mental Health, 2020). These indicators manifest clearly that adolescents and young people are highly prone to suffer from mental health problems during the pandemic. The preventive strategies of lockdowns, social distancing, and so forth, decrease social interactions while aiming to suppress virus transmission. In addition, mental distresses that are already common due to the pandemic, may be heavily exaggerated if less family support is available (Dsouza et al., 2020; Mamun, 2020; Pedrosa et al., 2020). Besides, remote schooling, potential sickness, economic shutdown, and so forth, play a role in their mental sufferings, which frequently mediates the suicidality risk (Erbacher, 2020). For instance, Mamun, Chandrima, et al. (2020) recently reported that online schooling related problems leading mother and son suicide‐pact in Bangladesh.

As the schools are employing virtual teaching methods, wherein, teachers are supposed to communicate with the adolescents online, so, becoming aware of any behavioral fluctuations is somewhat challenging (Erbacher, 2020). Thus, parents may find themselves to play the additional role of a teacher or counselor especially for the adolescents who may be showing signs of depression. But they may not be well informed of such sudden changes in their adolescents' behaviors which frequently leads them to mental instabilities as well as suicide risk (Erbacher, 2020; National Institute of Mental Health, 2020). Social workers, school counselors, psychologists, psychiatric professionals, and advanced practice psychiatric nurses offer accessibility through telehealth. However, access to such services is limited, and targeted delivery may be compromised because of paucity in the available information about adolescents' suicide‐related risky behaviors. As there is a paradigm shift in suicide nature and risk factors due to the ongoing pandemic; hence, exploring specific cohorts to understand suicide nature is warranted in adolescents. In this circumstance, the present study attempted to understand the adolescents' suicide risk and pattern for the first time across the world.

2. METHODS

As there is almost no updated information available on suicide in the national surveillance systems across the world (especially in the lower‐ and middle‐income countries) because of governments' focus on combating the physical issues of the ongoing pandemic; hence, the present study utilizes the press media reports of suicide cases (Mamun & Griffiths, 2020b). Research‐based on detailed and aggregated analysis of press reports of suicides is a well‐established method for retrospective studies in those countries where no functional national suicide databases exist (Mamun & Griffiths, 2020b). Moreover, in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic, the methods have been often used to perform suicide research works (e.g., Dsouza et al., 2020; Jahan et al., 2021; Panigrahi et al., 2021; Sripad et al., 2021; Syed & Griffiths, 2020).

A purposive sampling method via Google news search was used to collect the press media reporting of suicide cases. The news was searched using keywords combinations (in English and other languages) are as follows—(i) suicide, adolescent, COVID‐19; (ii) suicide, adolescent, COVID‐19, lockdown; (iii) suicide, teen, COVID‐19, lockdown; (iv) suicide, teen, corona, lockdown; (v) suicide, adolescent, corona, lockdown; (vi) kill self, adolescent, corona, lockdown; (vii) self‐killing, teen, corona, lockdown. Apart from English, reports were extracted from other 33 languages including Amharic, Arabic, Bengali, Chinese (Simplified), Danish, Dutch, English, Filipino, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Nepali, Persian, Russian, Spanish, Swedish, Tajik, Tamil, Tatar, Telugu, Thai, Turkish, Turkmen, Ukrainian, Urdu, Uyghur, Uzbek, Vietnamese, Welsh, Xhosa, Yiddish, Yoruba, and Zulu.

3. RESULTS

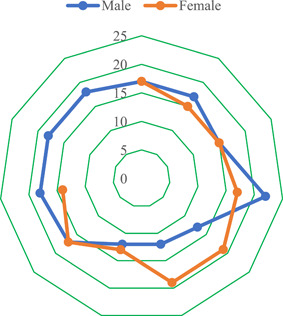

The suicide news reports between 15 February and 6 July were utilized and duplicated reports were screened and excluded. The final list comprised a total of 37 suicide cases across 11 countries. About three‐thirds of the suicides (73%) were reported in the months of April–May, 2020. More male suicides were reported (21 cases, i.e., 56.76%), and mean age of the total victims was 16.6 ± 2.7 (calculated for 29 cases for which exact age was available, ages were not reported in 8 cases) (Figure 1). Almost two‐thirds of the victims were from three countries namely India (11 cases), UK (8 cases), and the United States (6 cases). A total of 23 victims were students, of which 14 were school students. The most common method of suicide was reported to be hanging (19 out of a total of 26 reported cases, i.e., 73.07%). No exact stressors for suicide was reported in a total of 10 cases although, most of the suicide causalities were almost the same, which is related to mental instabilities such as depression, loneliness, psychological distress, etc. In addition, five victims were reported to have issues related to either online schooling or overwhelming academic distress, where two cases were reported for TikTok addiction‐related psychological distress and were tested for the COVID‐19 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of victims' age across gender (excluding four cases) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 1.

Distribution of COVID‐19‐related adolescent suicides

| Case | Reported date | Place | Profession | Gender | Age | Case description and suicide risk factor | Suicide method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 30 March | Alice Holt Forest, Surrey, UK | Student | Male | 17 | He was reported missing 11 days ago. He was upset with the cancellation of exams. Moreover, he was bothered that his exam results may depend on his mocks, in which his performance was not good | Not reported |

| 2 | 7 May | Tunbridge Wells, Kent, UK | Business student | Male | 17 | History of suicidal thoughts, he was concerned about his grades, struggled to adjust with lockdowns. He left home for a walk at 9 p.m. after leaving an emotional message for family on a mobile screensaver | Hanging |

| 3 | 31 March | Rhondda, South Wales, UK | School student | Male | 15 | He was feeling isolated because of the lockdown. He had no prior mental issues | Not reported |

| 4 | End of March | Greater Manchester, UK | Student and singer | Female | 17 | She had no prior mental health issues. She was frustrated and sad because of lockdown and felt restrictions that may never end | Not reported |

| 5 | 27 April | Gloucester, UK | Engineering student | Male | 22 | He was mentally overwhelmed by the impact of the lockdown as noted in the suicide note | Not reported |

| 6 | 7 April | Douai, North‐East France | School student | Male | 13 | He was overwhelmed by the amount of homework given during the lockdown period, which led to committing suicide | Hanging in room |

| 7 | 26 May | Mumbai, India | School student | Male | 12 | He killed himself after not being allowed to go outside of the home because of lockdown which made him depressed | Hanging from ceiling fan |

| 8 | 17 April | Texas, USA | School student | Male | 12 | His father believes that lockdown and being forced to stay at home led to depression and the desire to end his kid's life | Not reported |

| 9 | 12 April | California, USA | School student and athlete | Female | 15 | She was under stress because of “stay at home orders” as a result of the ongoing lockdown | Hanging |

| 10 | 30 March | Andhra Pradesh, India | Informal sector worker | Male | 17 | He was distressed after police arrested him for violating lockdown restrictions, who then released him. Later on, he shared a video message with friends and accused police of abetting his suicide | Hanging from tree |

| 11 | 11 April | Oakdale, California, USA | School student | Female | 15 | Nothing was reported about the sequence of events leading to suicide, but the school was closed because of the lockdown. The school is offering grief counseling to students | Gunshot injuries |

| 12 | 11 April | Oakdale, California, USA | School student | Female | 17 | Nothing was reported about the sequence of events leading to suicide, but the school was closed because of the lockdown. The school is offering grief counseling to students | Gunshot injuries |

| 13 | 7 April | Sacramento, California, USA | School student | Male | Not reported | Nothing specific was reported about the sequence of events leading to suicide, but lockdown, its distressing effect and need to connect and communicate was highlighted by the police | Not reported |

| 14 | 7 April | Sacramento, California, USA | School student | Female | Not reported | Nothing specific was reported about the sequence of events leading to suicide, but lockdown, its distressing effect and need to connect and communicate was highlighted by the police | Not reported |

| 15 | 18 March | King's Lynn, London, UK | Waitress | Female | 19 | She was unable to cope “with her world closing in, being stuck inside,” was also concerned about coronavirus and mental health issues related to isolation | Not reported |

| 16 | 17 April | Noida, UP, India | Student | Male | 18 | He was addicted to TikTok and was depressed at not getting likes on his video posts on the platform | Hanging from ceiling fan |

| 17 | 6 May | Bangalore, India | Student | Female | 19 | She was distressed to be stranded under the lockdown | Hanging from ceiling fan |

| 18 | 22 April | Sitapur, India | Not reported | Female | 13 | The girl secretly married and fled with her boyfriend in February and later on, she was moved to shelter‐home. Finally, she was refused to get back from there by parents (pre‐existing family conflict) | Hanging from ceiling fan |

| 19 | 1 May | Udaypur, Nepal | Informal sector worker, jobless after pandemic | Male | 18 | No specific details were reported, but implementations of lockdown made him jobless | Hanging from ceiling fan |

| 20‐21 | 7 April | Malawian area, UP, India | Not reported | Male | 18 (M) and 17 (F) | The boy and girl were in a relationship (so, this case is a suicide pact), stressing for not being able to move out and meet his partner because of lockdown | Hanging from tree |

| 22 | 7 May | Trinidad and Tobago | Student | Female | Not reported (teenage) | No specific details were reported but the implications of lockdown‐related home confinement and its effect on mental health were noted | Not reported |

| 23 | 1 June | Kerala, India | Student | Female | 14 | She was stressed for not being able to join online classes because of a lack of laptop and/or smartphone or functional television | Self‐immolation |

| 24 | 28 May | Mpumudde, Jinja town, Uganda | School student | Male | Not reported | He wrote a suicide note mentioning that one of the reasons was prolonged lockdown that led to the indefinite closure of schools | Hanging from ceiling fan |

| 25 | 15 May | Invercargill, New Zealand | Student | Male | 18 | No specific details were reported but the implications of lockdown‐related home confinement and its effect on mental health would have affected | Not reported |

| 26 | 20 May | Nuevo Tampico, Mexico | Not reported | Male | 17 | No specific details were reported, but conflict with parents is noted as a potential reason | Hanging from ceiling fan |

| 27‐30 | 2 May to 8 May | Kauai, Island in Hawaii | Not reported | Male | 20‐30 | No specific details were reported for each case, but stress and fear of COVID‐19 infection and economic crisis were alleged | Hanging |

| 31 | 29 April | Thailand | Not reported | Female | 20 | Lockdown related financial problems led her to suicide. She tried to raise money for raising children | Hanging from ceiling fan |

| 32 | 22 June | Rajkot, India | School student | Female | 12 | She was frustrated with online classes and homework during the lockdown. When asked by the mother to finish homework, she made an excuse and went inside her room and was later found hanging | Hanging from the ceiling |

| 33 | 16 June | Kerala, India | School student | Female | 15 | She was frustrated with online classes and difficulties in attending it because of a lack of resources | Hanging from ceiling fan |

| 34 | 3 July | Khaptad, Nepal | Not reported | Male | 18 | He was tested with COVID‐19 positive and committed suicide in the quarantine facility because of possible distress | Hanging from tree |

| 35 | 9 June | Ambedkar Nagar, India | School student | Female | 16 | She was depressed about being prevented from going out by parents because of lockdown | Hanging from ceiling fan |

| 36 | 29 April | UK | School student | Male | 17 | No specific detail was reported but the implications of lockdown‐related home confinement and its effect on mental health were noted | Not reported |

| 37 | 23 April | London, UK | Not reported | Female | 23 | She complained that life is getting miserable with each passing day in the pandemic, a day before the suicide, particularly feeling of loneliness was also reported | Jumping into the river |

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

4. DISCUSSION

This finding that most cases of suicides in the young people happened after a month of the implementation of lockdown and its various forms across countries of the world do indicate that public health policy needs to evolve to prevent such deaths in future pandemics. Previous epidemics have also shown that people are distressed by preventive measures of lockdown and quarantines. For instance, the quarantine time was reported to be enormously troublesome to some individuals, as stated in 15% of the severe acute respiratory syndrome quarantined persons in Toronto, who did not feel the necessity of quarantine (Hawryluck et al., 2004). The experience from previous epidemics and the COVID‐19‐related suicides in young people do necessitate exploration and implementation of strategies and methods to reduce lockdown‐related distress, especially in vulnerable groups. If such measures are not implemented then this may lead to double‐faced public health concerns during pandemics. One in which affected individuals may put their own life at risk (suicides are one expression). Second, folks escaping from these preventive measures can create a conflict because quarantine is essential to slow down the chances of virus transmission (Dsouza et al., 2020; Pedrosa et al., 2020). Besides, quarantine time without expressive and determined resolve may cause life‐threatening conditions in these cases (Hawryluck et al., 2004).

As aforementioned, for suppressing the virus transmission rate, preventive approaches like lockdown and social distancing for the general people, and isolation and quarantine for the suspected and confirmed cases are being applied throughout the entire world (Dsouza et al., 2020). But the implementation of lockdowns in the absence of a consensus and proper guidelines may cause unexpected problems that have been highlighted by many researchers (see Manzar et al. [2020] for details). However, these measures led to restricted movements and decreased social interactions with others, which may be extremely burdensome in some of the people. Such isolation and lack of social interaction influence people psychologically and emotionally, leading to a higher level of loneliness, anxiety, fear, stress, depression, tediousness, and so forth (Hossain et al., 2020; Islam et al., 2020; Pedrosa et al., 2020). As a result of unstable mental health, circumstances may easily lead the individual to suicidality increases, especially among teenagers (Mamun et al., 2021). This is because teenagers are more emotional, impulsive, and therefore, unable to cope with stressful situations. Therefore, they are more prone to take extreme steps. A recent review suggested that several suicide cofounders are common in youths, therefore, it is likely that suicide incidences can surge among the youths (Bilsen, 2018). For instance, these factors include—(i) mental disorders, (ii) previous suicide attempts, (iii) specific personality characteristics, (iv) genetic loading and family processes in combination with triggering psychosocial stressors, (vi) exposure to inspiring models, and (vii) availability of means of committing suicide (Bilsen, 2018). Therefore, it is not very surprising that this study identified suicide occurrences related to the lockdown‐related distress, movement restriction, not being able to socialize with friends, colleagues, and lovers, which makes them psychologically vulnerable. Although the present findings cannot verify all factors rather than stressful lockdown‐related mental instabilities, such information that is presented here may carry the appeal of the initial information for early detection of children and youths who may be vulnerable to suicide.

In children and adolescents, life events before suicidal behavior are usually academic stressors (including exam stress or bullying), family conflicts, disturbance, and other stressful life events (Erbacher, 2020). In this study, we found that the second most common reason attributed to suicides in these young people was stress related to studies, exams, grades, and difficulties in attending online classes because of resource constraints. Consistent with the present findings, some studies have also reported that academic issues are related to suicide during the pandemics (see Lathabhavan & Griffiths [2020]; Mamun, Chandrima, et al. [2020] for details). The National Center for Suicide Research and Prevention (2020) is trying to increase alertness about the potential increase in self‐harm and suicidal behavior as a consequence of the societal influence of the ongoing pandemic. Possible risk factors such as extended periods of social isolation, economic loss due to lockdown, fear of unemployment, death of family members, and significant others, etc., have been projected to precipitate self‐harm activities during this pandemic crisis. However, it is an important highlight that these efforts by the NASP and other bodies need to include demographic‐specific indicators/signs of self‐harm and suicides in their information sheets. For instance, in this suicide report of 37 young people, few cases were attributed to fear of COVID‐19 infection, financial crisis, and previous history of suicidal thoughts/actions. This pattern is very different from COVID‐19‐related suicides reported from Indian general population, where fear of infection, financial crisis, and social boycott were major factors (see Dsouza et al., [2020] for one of the largest press media reporting suicide study). Similarly, the present findings about major causative factors of suicide differed from the studies conducted in the general population in Bangladesh (Bhuiyan et al., 2020; Mamun & Griffiths, 2020a), Pakistan (Mamun & Ullah, 2020), as well as the global context (Griffiths & Mamun, 2020). In contrast, PUBG‐gaming related three suicide cases among adolescents and youths are alleged in Pakistan (Mamun et al., 2020c), which alludes to the present finding of TikTok related suicidality. All these shows that there are age‐specific differences in perceived factor involved in the causality of suicides during the lockdowns.

One of the disturbing trends was that one‐third of suicides was in school going teens. The subject of suicides in teens during a pandemic is less understood and continuously developing. This may be a multifaceted topic, and public policymakers, psychiatrists, mental health services need to work in a concerted and tandem manner to prevent such deaths. Apart from the problems of age at which children cannot fully recognize the outcome of their actions, there are frequently familial issues involved in suicides in this age group. These familial issues may often go unnoticed and underreported. Suicides in the very young are often termed accidents on death inquiries, apparently due to these issues (Zainum & Cohen, 2017). Finally, it is important to note that the COVID‐19‐related suicides in young people were distributed across both developing and developed parts of the world. This implies that resources and strategies are either not available or are not effective in preventing epidemic‐related suicides among young people. This finding is contrary to that of suicide cases in the general population which is usually higher in LMICs (World Health Organization, 2014). This is perhaps the most concerning findings that strongly indicate the need for a rigorous and comprehensive strategy to manage and reduce incidences of suicides among young people during epidemics. Nevertheless, to respond to this mounting public health issue effectively, we must first try to understand the factors and causes leading to the rise in suicide rates.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The study can be partially limited because of extracting suicide causalities from press media, although the method has been applied by previous research on pandemic‐related suicide studies (e.g., Dsouza et al., 2020; Jahan et al., 2021; Panigrahi et al., 2021; Sripad et al., 2021; Syed & Griffiths, 2020). Besides, the suicide risk factors reported herein has limited face value of taking as factual because psychological autopsies were not performed. Despite the limitation, this is the first study to investigate suicide‐related trends in adolescent and youth people during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Some of the important trends from the study were (i) most of these suicides happened in the months of April–May, that is, after a month of lockdowns, (ii) suicides were reported from both developing and developed parts of the world, (iii) about one‐third of suicides were in school going teens‐ an alarming trend, (iv) hanging was the most common mode, and (v) lockdown‐related distress and stress of exams, studies, grades, etc., were two most common stressors attributed to these suicides.

6. PRACTICAL IMPLEMENTATIONS

The present findings may help in suicide prevention actions, increasing awareness of suicidal behavior, and familiarization of warning signs. The age‐specific causative factors of suicides in adolescents and youths may be explored further to develop a strategy to screen, and identify youths with suicidal behavior during epidemics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Majmaah University for funding this study under Project Number No (R‐2021‐67).

Manzar, M. D. , Albougami, A. , Usman, N. , & Mamun, M. A. (2021). Suicide among adolescents and youths during the COVID‐19 pandemic lockdowns: A press media reports‐based exploratory study. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 34,139–146. 10.1111/jcap.12313

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Bhuiyan, A. K. M. I. , Sakib, N. , Pakpour, A. H. , Griffiths, M. D. , & Mamun, M. A. (2020). COVID‐19‐related suicides in Bangladesh due to lockdown and economic factors: Case study evidence from media reports. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s11469-020-00307-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsen, J. (2018). Suicide and youth: risk factors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 540. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dsouza, D. D. , Quadros, S. , Hyderabadwala, Z. J. , & Mamun, M. A. (2020). Aggregated COVID‐19 suicide incidences in India: Fear of COVID‐19 infection is the prominent causative factor. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113145. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbacher, T. , 2020. Youth suicide risk during COVID‐19: How parents can help. https://www.inquirer.com/health/expert-opinions/coronavirus-teen-suicide-risk-parents-help-20200504.html

- Griffiths, M. D. , & Mamun, M. A. (2020). COVID‐19 suicidal behavior among couples and suicide pacts: Case study evidence from press reports. Psychiatry Research, 289, 113105. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawryluck, L. , Gold, W. L. , Robinson, S. , Pogorski, S. , Galea, S. , & Styra, R. (2004). SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10, 1206–1212. 10.3201/eid1007.030703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M. M. , Rahman, M. , Trisha, N. F. , Tasnim, S. , Nuzhath, T. , Hasan, N. T. , Clark, H. , Das, A. , McKyer, E. L. J. , & Ahmed, H. U. , 2020. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in South Asia during COVID‐19: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. PsyArXiv [Preprint]. 10.31234/osf.io/q4k5b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Islam, S. M. D. U. , Bodrud‐Doza, M. , Khan, R. M. , Haque, M. A. , & Mamun, M. A. (2020). Exploring COVID‐19 stress and its factors in Bangladesh: A perception‐based study. Heliyon, 6, e04399. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahan, I. , Ullah, I. , Griffiths, M. D. , & Mamun, M. A. (2021). COVID‐19 suicide and its causative factors among the healthcare professionals: Case study evidence from press reports. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. Advance online publication. 10.1111/ppc.12739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, K. S. , Mamun, M. A. , Griffiths, M. D. , & Ullah, I. (2020). The mental health impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic across different cohorts. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s11469-020-00367-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathabhavan, R. , & Griffiths, M. (2020). First case of student suicide in India due to the COVID‐19 education crisis: A brief report and preventive measures. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 53, 102202. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun, M. A. (2020). The first COVID‐19 triadic (homicide!)‐suicide pact: Do economic distress, disability, sickness, and treatment negligence matter? Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. Advance online publication. 10.1111/ppc.12686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun, M. A. , Bodrud‐Doza, M. , & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Hospital suicide due to non‐treatment by healthcare staff fearing COVID‐19 infection in Bangladesh? Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 102295. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun, M. A. , Chandrima, R. M. , & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Mother and son suicide pact due to COVID‐19‐related online learning issues in Bangladesh: An unusual case report. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s11469-020-00362-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun, M. A. , & Griffiths, M. D. (2020a). First COVID‐19 suicide case in Bangladesh due to fear of COVID‐19 and xenophobia: Possible suicide prevention strategies. Asian J Psychiatr, 51, 102073. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun, M. A. , & Griffiths, M. D. (2020b). Mandatory Junior School Certificate exams and young teenage suicides in Bangladesh: a response to Arafat (2020). International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s11469-020-00324-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun, M. A. , Sakib, N. , Gozal, D. , Bhuiyan, A. K. M. I. , Hossain, S. , Bodrud‐Doza, M. , Al Mamun, F. , Hosen, I. , Safiq, M. B. , & Abdullah, A. H. (2021). The COVID‐19 pandemic and serious psychological consequences in Bangladesh: A population‐based nationwide study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 462–472. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun, M. A. , & Ullah, I. (2020). COVID‐19 suicides in Pakistan, dying off not COVID‐19 fear but poverty? – The forthcoming economic challenges for a developing country. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 163–166. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun, M. A. , Ullah, I. , Usman, N. , & Griffiths, M. D. (2020c). PUBG‐related suicides during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Three cases from Pakistan. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. Advance online publication. 10.1111/ppc.12640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzar, M. D. , Pandi‑Perumal, S. , & BaHammam, A. (2020). Lockdowns for community containment of COVID‑19: Present challenges in the absence of interim guidelines. Journal of Natural and Science of Medicine, 3, 318–321. 10.4103/JNSM.JNSM_68_20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miron, O. , Yu, K.‐H. , Wilf‐Miron, R. , & Kohane, I. S. (2019). Suicide rates among adolescents and young adults in the United States, 2000‐2017. Journal of the American Medical Association, 321, 2362–2364. 10.1001/jama.2019.5054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention , 2020. The Coronavirus: Risk for increased suicide and self‐harm in the society after the pandemic. https://ki.se/en/nasp/the-coronavirus-risk-for-increased-suicide-and-self-harm-in-the-society-after-the-pandemic

- National Institute of Mental Health , 2020. Helping children and adolescents cope with disasters and other traumatic events: What parents, rescue workers, and the community can do. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/helping-children-and-adolescents-cope-with-disasters-and-other-traumatic-events/index.shtml

- Panigrahi, M. , Pattnaik, J. I. , Padhy, S. K. , Menon, V. , Patra, S. , Rina, K. , Padhy, S. S. , & Patro, B. (2021). COVID‐19 and suicides in India: A pilot study of reports in the media and scientific literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 57, 102560. 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrosa, A. L. , Bitencourt, L. , Fróes, A. C. F. , Cazumbá, M. L. B. , Campos, R. G. B. , de Brito, S. B. C. S. , & e Silva, A. C. (2020). Emotional, behavioral, and psychological impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2635. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripad, M. N. , Pantoji, M. , Gowda, G. S. , Ganjekar, S. , Reddi, V. S. K. , & Math, S. B. (2021). Suicide in the context of COVID‐19 diagnosis in India: Insights and implications from online print media reports. Psychiatry Research, 57, 113799. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed, N. K. , & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Nationwide suicides owing to alcohol withdrawal symptoms during COVID‐19 pandemic: A review of cases from media reports. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 130, 289–291. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization , 2014. Preventing suicide: A global imperative. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/131056/9789241564779-ger.pdf

- World Health Organization , 2020. Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID‐19,outbreak. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331490/WHO-2019-nCoV-MentalHealth-2020.1-eng.pdf

- Zainum, K. , & Cohen, M. C. (2017). Suicide patterns in children and adolescents: A review from a pediatric institution in England. Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology, 13, 115–122. 10.1007/s12024-017-9860-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.