Abstract

Semaglutide, a glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) analogue, has been coformulated in a tablet with the absorption enhancer, sodium N‐(8‐[2‐hydroxybenzoyl] amino) caprylate (SNAC). We investigated tablet erosion and the pharmacokinetics of oral semaglutide administered with 2 different water volumes and evaluated the relationships between these parameters. In a randomized, single‐center (Quotient Sciences, UK), open‐label, 2‐period crossover trial, 26 healthy men received single doses of 10 mg oral semaglutide with 50 or 240 mL water while fasting. Tablet erosion and gastrointestinal transit were assessed by gamma scintigraphy. Semaglutide and SNAC plasma concentrations were measured until 24 and 6 hours, respectively, after administration. Complete tablet erosion (CTE) occurred in the stomach irrespective of water volume administered with the tablet (primary end point). Mean time to CTE was 85 versus 57 minutes with 50 versus 240 mL water (ratio 50/240 mL, 1.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.96‐2.37; P = .072). Area under the semaglutide concentration‐time curve from 0 to 24 hours (AUC0‐24h,semaglutide) and maximum semaglutide concentration (Cmax,semaglutide) were ∼70% higher with 50 versus 240 mL water (P = .056 and P = .048, respectively). Median time to maximum semaglutide concentration (tmax,semaglutide) was 1.5 hours independent of water volume with dosing. Higher AUC0‐24h,semaglutide and Cmax,semaglutide and longer tmax,semaglutide were significantly correlated with longer time to CTE and later gastric emptying of tablet and water (all P < .05). The safety profile was as expected for the GLP‐1 receptor agonist drug class. In conclusion, the oral semaglutide tablet erodes in the stomach irrespective of water volume with dosing. Slower tablet erosion in the stomach results in higher semaglutide plasma exposure.

Keywords: gastrointestinal transit, gastric absorption, glucagon‐like peptide‐1, scintigraphy, sodium N‐(8‐[2‐hydroxybenzoyl] amino) caprylate

Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonists stimulate insulin secretion and inhibit glucagon release in a glucose‐dependent manner, which improves glycemic control with a low risk of hypoglycemia. Unlike many other therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus, GLP‐1 receptor agonists have been shown to also reduce body weight. 1 , 2 Within this class, semaglutide is a human GLP‐1 analogue that was approved for subcutaneous administration by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 and by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2018. Semaglutide has 94% structural homology to human GLP‐1, but with important modifications to increase its binding to albumin and to make it more resistant to degradation by dipeptidyl peptidase‐4, resulting in an extended half‐life of approximately 1 week. 3 , 4 Clinical trials with once‐weekly subcutaneous administration of semaglutide have demonstrated effective glucose control, reduced body weight, and cardiovascular risk reduction. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8

Oral drug administration is preferable over other routes of delivery for some patients, primarily because of dosing convenience and hence patient acceptance and adherence. 9 , 10 However, for protein‐ and peptide‐based drugs like GLP‐1 analogues, degradation in the stomach because of low pH and proteolytic enzymes is a major barrier to achieving sufficiently high systemic bioavailability after oral administration. Furthermore, absorption of proteins and peptides is compromised by the limited permeability through the gastrointestinal epithelium. 9 , 10

To overcome these challenges, an oral tablet formulation of semaglutide has been developed by coformulation with the absorption enhancer sodium N‐(8‐[2‐hydroxybenzoyl] amino) caprylate (SNAC). Oral semaglutide once daily was approved by the FDA in 2019 and by the EMA in 2020. Based on in vitro and animal studies, SNAC is thought to protect against proteolytic degradation of semaglutide through a localized increase in pH and to facilitate the absorption of semaglutide across the gastric epithelium primarily via the transcellular route. 11 The absorption‐enhancing effect of SNAC on semaglutide was shown to be strictly time‐ and molecular size‐dependent, and the bioavailability of oral semaglutide has been assessed in dogs to be 1%‐2%. 11 The biological activity of semaglutide is not altered by the presence of SNAC. 12 Oral semaglutide is the first GLP‐1 receptor agonist developed for oral administration.

The purpose of the present trial was to better understand the absorption of oral semaglutide in humans. First, the anatomical site of tablet erosion, rate of tablet erosion, and gastrointestinal transit of the oral semaglutide tablet were investigated using gamma scintigraphy, a widely used noninvasive technique to evaluate pharmaceutical drug delivery systems. 13 , 14 Second, the correlation between scintigraphic parameters and the pharmacokinetic properties of semaglutide was examined to elucidate if tablet erosion kinetics may influence the extent of absorption of oral semaglutide. Third, the effect of water volume administered with dosing on tablet erosion kinetics and pharmacokinetic properties of oral semaglutide was evaluated. Previously, absorption of the hormone peptide salmon calcitonin, coformulated with another absorption enhancer, 8‐(N‐2‐hydroxy‐5‐chlorobenzoyl)‐amino‐caprylic acid (5‐CNAC), was higher when administered orally with 50 versus 200 mL of water. 15 Thus, investigating 2 different water volumes in the present trial was expected to provide further insight into the relationship between tablet erosion kinetics and pharmacokinetics of oral semaglutide across a wider span of absorption rates.

Methods

Trial Design

The trial protocol and the subject information/informed consent form were reviewed and approved by an appropriately constituted review board (National Research Ethics Service Committee East of England) and by appropriate health authorities according to local regulations. The trial was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice. All subjects provided written informed consent prior to any trial‐related activities. The radiation dose equivalent received by each subject during the scintigraphic procedures did not exceed 0.49 mSv per dosing visit and was approved by the Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee, Oxfordshire, UK. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (trial identifier: NCT01619345). A minor part of the results of the current trial has been published previously. 11

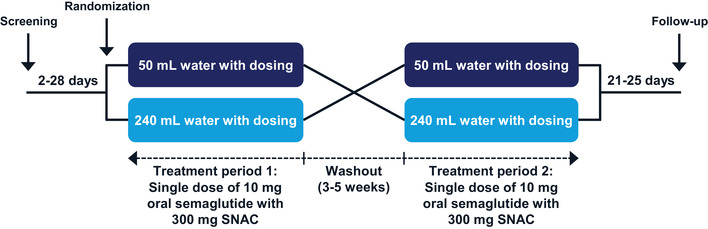

This was a randomized, single‐center (Quotient Sciences, Nottingham, UK), open‐label, 2‐period crossover trial (Figure 1). The trial consisted of a screening visit (2‐28 days before the first dosing), 2 treatment periods separated by a 3‐ to 5‐week washout, and a follow‐up visit (21‐25 days after the second dosing).

Figure 1.

Trial design. SNAC, sodium N‐(8‐[2‐hydroxybenzoyl] amino) caprylate.

Participants

Eligible subjects were healthy men aged 18‐64 years with a body mass index (BMI) of 18.5‐30.0 kg/m2. Subjects were excluded if they had clinically significant concomitant diseases or disorders, clinically significant abnormal values in clinical laboratory screening tests, any history of gastrointestinal surgery or gastrointestinal disorder, had used GLP‐1 receptor agonists within 3 months prior to first dosing of trial product, or were smokers.

Procedures

Subjects received single doses of an oral semaglutide tablet (10 mg semaglutide coformulated with 300 mg SNAC; tablet size 7.5 × 13.0 mm; Novo Nordisk, Bagsværd, Denmark) administered in the fasting state with 50 and 240 mL of water, respectively, in the 2 treatment periods in randomized sequence (Figure 1). Subjects were always assigned the lowest available randomization number, and the randomized treatment sequence was not revealed before a subject was randomized. Allocation of treatment sequence was done by qualified staff at the clinical site.

At each dosing visit, subjects attended the clinical site in the evening on the day before dosing. Subjects received an evening snack and initiated an overnight fast of ≥8 hours (water ad libitum was allowed until 2 hours before dosing). The dosing visit was rescheduled if the subjects had experienced acute diarrhea or constipation during the last 7 days prior to dosing, had consumed items likely to disturb gastrointestinal transit time as judged by the Investigator, liquids or food containing poppy seeds, grapefruit, cranberry, caffeine, or other xanthines during the 48 hours prior to dosing or had consumed alcohol or changed their exercise pattern or daily routine during the 24 hours prior to dosing. On the dosing day, trial product administration occurred between 8:00 am and 11:00 am, with subjects in an upright position, and was followed by ≥4 hours of postdose fasting (except for 200 mL of water 2 hours after dosing).

Gastrointestinal transit of the oral semaglutide tablet and tablet erosion were assessed by gamma scintigraphy using a gamma camera (General Electric Maxicamera, GE Company, Boston, Massachusetts) with a 40‐cm field of view and fitted with a medium energy parallel hole collimator. Oral semaglutide tablets contained 111In‐labeled ion‐exchange resin (maximum of 1 MBq), and the water used for tablet administration was labeled with 99mTc (maximum of 4 MBq, to provide an outline of the gastrointestinal tract and to assess gastrointestinal transit of the water administered with the tablet). Dynamic single‐isotope (111In) imaging of the esophagus, consisting of sequential images of a 0.5‐second duration, was performed during the first minute after dosing while subjects were sitting. Subsequently, while subjects were standing, static dual‐isotope (111In and 99mTc) images of the abdomen of approximately a 50‐second duration were recorded approximately every 3 minutes from 1 until 10 minutes after dosing, then at 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, and 50 minutes, and then every 20 minutes from 1 hour until 4 hours after dosing. Subjects were allowed to sit or remain moderately active in‐between static imaging times. Anatomical markers (containing no more than 0.05 MBq 111In) were used to align sequential images during the analysis. After completion of the scintigraphic imaging, subjects were served standard mixed meals for the rest of the stay at the clinic, whereas fluids were permitted ad libitum.

Blood samples for determination of semaglutide concentration in plasma were drawn 30 minutes before dosing (predose) and 30 minutes and 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12, and 24 hours after dosing. Blood samples for determination of SNAC concentration in plasma were drawn 30 minutes before dosing (predose) and 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 minutes and 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, and 6 hours after dosing. Subjects were discharged from the clinic after the last pharmacokinetic blood sample 24 hours after dosing.

Assessments

The scintigraphic data were analyzed using MicasXplus processing software as previously described. 16 To avoid bias, these analyses were performed blinded to the amount of water volume with dosing.

Semaglutide and SNAC were measured by validated assays using plasma protein precipitation, followed by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry detection as previously described. 17

Safety assessments included adverse events (AEs), hypoglycemic episodes, laboratory safety parameters, physical examination, vital signs, and electrocardiogram.

End Points

Qualitative scintigraphic end points included the primary end point, anatomical location of the tablet at the time of complete tablet erosion (CTE; defined as dispersion of the entire radioactive marker into the gastrointestinal tract with no signs of a distinct “core” remaining), and the secondary end points: esophageal transit time (time from the first image in which the tablet was located in the esophagus until the first image in which the tablet was no longer present in the esophagus), esophageal stasis (defined as an esophageal transit time > 20 seconds), time to initial tablet erosion (defined as the first sign of sustained release of the radioactive marker from the tablet), time to CTE, time to complete gastric emptying of the tablet (defined as the time at which the radioactive marker of the tablet was no longer present in the stomach), and time to complete gastric emptying of water (defined as the time at which the radioactive marker of the water was no longer present in the stomach). Furthermore, the quantitative scintigraphic end point time to 50% of CTE was derived.

Pharmacokinetic end points included area under the semaglutide plasma concentration‐time curve from 0 to 24 hours (AUC0‐24h,semaglutide, determined using a standard noncompartmental method applying the trapezoidal rule on observed concentrations and the actual sampling times), maximum semaglutide plasma concentration (Cmax,semaglutide), time to maximum semaglutide plasma concentration (tmax,semaglutide), area under the SNAC plasma concentration‐time curve from 0 to 6 hours (AUC0‐6h,SNAC, determined as described above for AUC0‐24h,semaglutide), maximum SNAC plasma concentration (Cmax,SNAC), and time to maximum SNAC plasma concentration (tmax,SNAC).

Statistical Analyses

Sample size determination was based on an analysis of the primary end point, anatomical location of the tablet at CTE, using McNemar's exact test in a 2 × 2 contingency table. Assuming a probability ≥ 75% that CTE occurred in the stomach when the tablet was dosed with 50 mL and a probability ≥ 75% that CTE occurred in the proximal small bowel when the tablet was dosed with 240 mL water, 22 completing subjects were required to detect a difference in tablet location at CTE between water volumes with 87% power at a significance level of 5%. A total of 26 subjects were randomized in the trial to account for potentially withdrawn subjects.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS versions 9.3 or 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). All statistical tests were 2‐sided with 5% significance level and performed on the full analysis set comprising all randomized subjects receiving at least 1 dose of trial product. The analysis of the primary end point was controlled for type 1 error. Other analyses were not controlled for multiplicity. The time to an event in scintigraphic end points was censored at 4 hours if the event did not occur within the 4‐hour scintigraphic imaging period.

The planned analysis of the primary end point, anatomical location of the tablet at CTE, could not be performed because CTE occurred in the stomach for all evaluated subjects with both water volumes. Thus, the primary end point was only summarized by descriptive statistics.

Time to initial tablet erosion, time to CTE, AUC0‐24h,semaglutide, Cmax,semaglutide, AUC0‐6h,SNAC, and Cmax,SNAC were log‐transformed and compared between the 2 water volumes using linear mixed models with water volume and period as fixed effects and subject as a random effect. The models for AUC0‐24h,semaglutide and Cmax,semaglutide allowed for left‐censoring (because all semaglutide plasma concentrations were below the lower limit of quantification [LLOQ] of 0.73 nmol/L in 3 subjects when receiving 240 mL water with dosing).

To evaluate if semaglutide pharmacokinetics were correlated with time to CTE, time to complete gastric emptying of the tablet, and time to complete gastric emptying of water, AUC0‐24h,semaglutide, Cmax,semaglutide, and tmax,semaglutide were log‐transformed and analyzed in linear mixed models with the respective log‐transformed scintigraphic end point as covariate, water volume and period as fixed effects, and subject as a random effect. The covariate coefficient, β, was estimated and a test of β = 0 was performed (ie, no correlation between the respective scintigraphic end point and the respective pharmacokinetic end point). Furthermore, for the relation between time to CTE and the pharmacokinetic end points, the value 2β was estimated including the 95% confidence interval (CI). The value 2β expressed the estimated fold change in AUC0‐24h,semaglutide, Cmax,semaglutide, or tmax,semaglutide, if time to CTE was doubled. For the correlation analyses, in the 3 subjects with all semaglutide plasma concentrations below LLOQ for 240 mL of water with dosing, AUC0‐24h,semaglutide was imputed with 0.5 × LLOQ multiplied by the arithmetic mean of tmax,semaglutide for the evaluable profiles when administered with 240 mL water, whereas Cmax,semaglutide was imputed with 0.5 × LLOQ.

Safety end points were summarized by descriptive statistics using the safety analysis set comprising all subjects receiving at least 1 dose of trial product. Hypoglycemic episodes were defined as “severe” when they required third‐party assistance, that is, according to the American Diabetes Association, 18 and as “confirmed” when they were either “severe” or verified by a plasma glucose level of <3.1 mmol/L.

Results

Subject Disposition and Characteristics

Subject disposition is provided in Supplemental Figure S1. A total of 112 subjects were screened, 29 were enrolled, 27 were randomized, 26 were exposed to trial product, and 24 completed the trial. All 26 exposed subjects were included in the safety analysis set and in the full analysis set. For 1 subject, scintigraphic results (except esophageal transit time) after dosing with 240 mL water were excluded because the scintigraphic imaging was terminated because of an AE of vomiting.

The 26 exposed subjects were all healthy men and had a mean ± standard deviation age of 38 ± 11 years, body weight of 83.4 ± 11.0 kg, height of 1.79 ± 0.07 m, and BMI of 25.9 ± 2.3 kg/m2. The majority of subjects (22) were White, whereas 3 were Asian, and 1 was Black/African American.

Scintigraphic Results

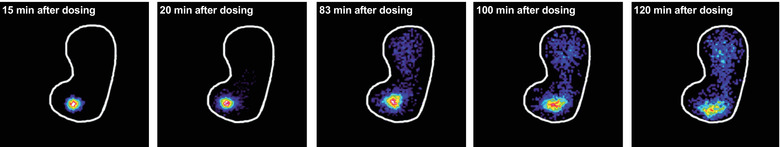

Representative scintigraphic images of tablet erosion are shown in Figure 2. CTE occurred in the stomach for all evaluated subjects irrespective of water volume administered with the tablet. Time to CTE was numerically ∼50% longer after dosing with 50 versus 240 mL water, although this was not statistically significant. The estimated mean time to CTE was 85 minutes (95% CI, 62‐118 minutes) versus 57 minutes (95% CI, 41‐77 minutes) for dosing with 50 versus 240 mL water, respectively (ratio 50/240 mL, 1.51; 95% CI, 0.96‐2.37; P = .072). The geometric mean time to 50% of CTE was 28.8 minutes (coefficient of variation [CV], 79%) versus 26.7 minutes (CV, 100%) with a water volume of 50 versus 240 mL.

Figure 2.

Gamma scintigraphic imaging of tablet erosion in the stomach from 15 to 120 minutes after a single dose of 10 mg oral semaglutide containing 111In‐labeled ion‐exchange resin in a representative healthy male subject receiving 50 mL water with dosing. The white line shows the stomach outline. The intense colors within the stomach (eg, red/yellow/green/blue) represent the tablet core and released radioactivity.

Tablet erosion commenced soon after dosing, within ∼3 minutes independent of water volume administered with the tablet. The estimated mean time to initial tablet erosion was 2.4 minutes (95% CI, 1.3‐4.4 minutes) versus 3.3 minutes (95% CI, 1.8‐6.0 minutes) for dosing with 50 versus 240 mL water, respectively (ratio 50/240 mL, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.34‐1.55; P = .399).

The geometric mean esophageal transit time was 1.8 seconds after dosing with both 50 and 240 mL water. Individual esophageal transit time ranged from 0.6 to 10.8 seconds. Thus, no subjects experienced esophageal stasis, predefined as a transit time > 20 seconds.

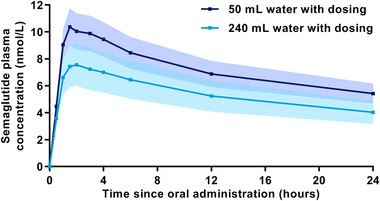

Semaglutide Pharmacokinetics

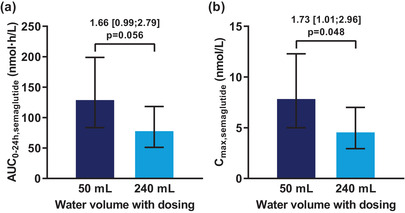

Semaglutide plasma concentration‐time profiles are shown in Figure 3. Median tmax,semaglutide was 1.5 hours for both water volumes with a range of 0.5‐3.0 hours for 50 mL and a range of 0.5‐4.0 hours for 240 mL. AUC0‐24h,semaglutide and Cmax,semaglutide were approximately 70% higher when dosed with 50 versus 240 mL water (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Arithmetic mean semaglutide plasma concentration‐time profiles after a single dose of 10 mg oral semaglutide with 50 or 240 mL water in healthy male subjects. Error bands (dark blue shading for 50 mL water and lighter blue shading for 240 mL water) show ± standard error. Values below LLOQ were set to zero. n = 24 (50 mL) or n = 26 (240 mL). Conversion factor from molar concentration (nmol/L) to mass concentration (ng/mL), 4.11358.

Figure 4.

Effect of water volume with dosing on (a) AUC0‐24h,semaglutide and (b) Cmax,semaglutide after a single dose of 10 mg oral semaglutide in healthy male subjects. Bars are estimated means and 95% CIs. Treatment comparisons show estimated treatment ratios (95% CI) and P value. End points were analyzed on a logarithmic scale but are presented on the linear scale. n = 24 (50 mL) or n = 26 (240 mL). Cmax, maximum concentration. Conversion factor from molar concentration (nmol/L) to mass concentration (ng/mL), 4.11358.

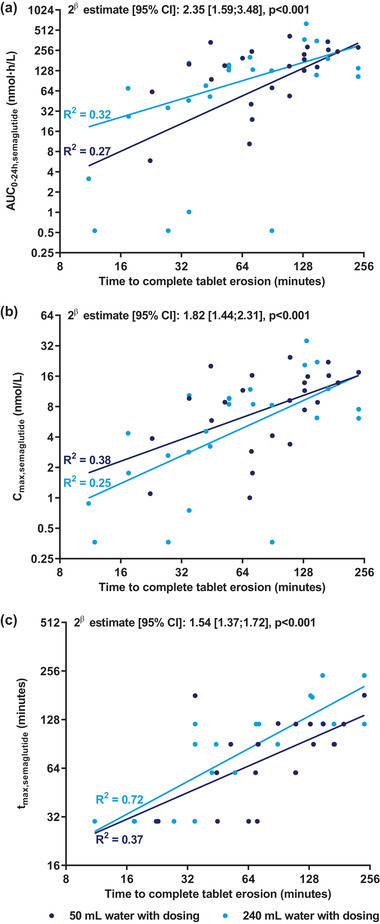

Relationship Between Tablet Erosion Kinetics and Semaglutide Pharmacokinetics

Higher semaglutide exposure (AUC0‐24h,semaglutide and Cmax,semaglutide) and longer tmax,semaglutide were significantly correlated with longer time to CTE (Figure 5). The estimates for 2β were close to 2 for AUC0‐24h,semaglutide and Cmax,semaglutide and close to 1.5 for tmax,semaglutide, implying that a doubling of the time to CTE results in an approximately 2‐fold increase in AUC0‐24h,semaglutide and Cmax,semaglutide and approximately 50% longer tmax,semaglutide.

Figure 5.

Relationship between time to complete tablet erosion and (a) AUC0‐24h,semaglutide, (b) Cmax,semaglutide, and (c) tmax,semaglutide after a single dose of 10 mg oral semaglutide in healthy male subjects. Lines represent the simple regression lines for dose administration with 50 and 240 mL of water, respectively. R 2 values were calculated as 1 − SSModel/SSTotal, where SSModel is the sum of squared residuals from the simple regression model (the log‐transformed pharmacokinetic end point displayed on the y axis regressed on the log‐transformed time to complete tablet erosion) for each water volume, and SSTotal is the total sum of squares. Note that both horizontal and vertical axes are presented using logarithmic scale. β is the covariate coefficient in a linear mixed model with log‐transformed pharmacokinetic end point as dependent variable, water volume and period as fixed effects, subject as random effect, and the log‐transformed time to complete tablet erosion as covariate. Note that there was no statistically significant interaction between water volume and time to complete tablet erosion for AUC0‐24h,semaglutide, Cmax,semaglutide, and tmax,semaglutide (P = .47, P = .81, and P = .46, respectively), that is, there was no statistically significant difference between the slopes for the 2 water volumes. The value 2β expresses the estimated fold change in AUC0‐24h,semaglutide, Cmax,semaglutide, or tmax,semaglutide if time to complete tablet erosion is doubled. The P value is for a test of β = 0, which indicates no correlation between time to complete tablet erosion and the pharmacokinetic end point. n = 24 (50 mL), n = 25 (240 mL) in (a, b) or n = 22 (240 mL) in (c). Cmax, maximum concentration; tmax, time to maximum concentration.

Likewise, it was found that higher AUC0‐24h,semaglutide and Cmax,semaglutide and longer tmax,semaglutide were significantly correlated with later gastric emptying of the radioactive marker of the tablet and with slower gastric emptying of the radioactive marker of the water (P < .05 for all).

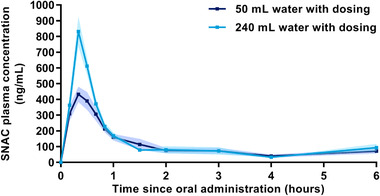

SNAC Pharmacokinetics

SNAC plasma concentration‐time profiles indicated a lower peak plasma concentration of SNAC when oral semaglutide was administered with 50 mL water compared with 240 mL water (Figure 6). Accordingly, AUC0‐6h,SNAC was 19% lower and Cmax,SNAC was 38% lower when oral semaglutide was dosed with 50 versus 240 mL water (Supplemental Figure S2). Median tmax,SNAC was 0.3 hours for both water volumes.

Figure 6.

Arithmetic mean SNAC plasma concentration‐time profiles after a single dose of 10 mg oral semaglutide with 50 or 240 mL water in healthy male subjects. Error bands (dark blue shading for 50 mL water and lighter blue shading for 240 mL water) show ± standard error. Values below LLOQ were set to zero. n = 24 (50 mL) or n = 26 (240 mL).

Safety

A total of 54 AEs were reported in 18 subjects (69%) during the trial. The most frequently reported AEs were headache (reported in 17% and 23% of subjects for 50 and 240 mL water, respectively), nausea (21% and 12%), and vomiting (17% and 12%). A total of 7 events of headache occurred on the day of dosing, whereas 3 events of headache occurred 8, 20, and 22 days after dosing, respectively. All subjects recovered from the events of headache within 1–2 days. All the events of vomiting and all except 1 of the events of nausea occurred on the day of dosing, and subjects recovered within 1‐2 days. The last event of nausea occurred 2 days after dosing, and the subject recovered within 6 days. No severe or serious AEs were reported during the trial. The majority of AEs were mild (47 events), whereas 7 AEs were moderate (these all occurred on the day of dosing and subjects recovered within 1 day, except for an event of hand fracture [broken finger] that occurred 5 days after dosing, and the subject recovered within 16 days). No severe or confirmed hypoglycemic episodes were reported during the trial, and there were no clinically relevant observations related to vital signs, physical examination, or electrocardiogram. There were no clinically relevant observations in laboratory safety parameters, except temporary asymptomatic increased amylase and lipase levels in 1 subject on the day after first dosing, which had returned to normal levels 5 days later.

Discussion

The key results were that CTE of oral semaglutide occurred in the stomach irrespective of water volume administered with dosing and that higher systemic semaglutide exposure and longer time to maximum semaglutide plasma concentration both correlated with longer time to CTE. Furthermore, semaglutide exposure was 70% higher after dosing of the oral semaglutide tablet with 50 versus 240 mL water. With an oral semaglutide tablet size of 7.5 × 13.0 mm, passage of the tablet from the stomach to the duodenum during phase III of the migrating motor complex could have been possible. However, this was not observed. The tablet did not pass to the duodenum in intact form in any of the subjects.

Because of the presence of low pH and proteolytic enzymes, it would be expected that a peptide‐based drug like semaglutide would be rapidly degraded in the stomach. Nonetheless, the observed correlations between longer time to complete gastric emptying and greater semaglutide exposure may lead to the interpretation that the longer the tablet remains in the stomach, the higher the systemic exposure of semaglutide. Taken together with the finding that complete erosion of the oral semaglutide tablet occurs in the stomach, this suggests that orally administered semaglutide is absorbed in the stomach through localized absorption‐enhancing effects of SNAC. This is in line with conclusions drawn based on recent animal data, including the finding that prevention of intestinal absorption by pyloric ligation in dogs did not result in decreased semaglutide plasma exposure compared with that seen in nonligated dogs after administration of oral semaglutide. 11

Interestingly, a pharmacoscintigraphic study on insulin coformulated with the absorption enhancer monosodium N‐(4‐chlorosalicyloyl)‐4‐aminobutyrate (4‐CNAB) also suggested that absorption occurred in the stomach. 19 The current finding of a correlation between longer time to CTE and higher semaglutide exposure does not provide evidence of a causal relationship. Still, it may be speculated if slower tablet erosion could lead to a more optimal rate of release of semaglutide and SNAC molecules from the tablet to facilitate semaglutide absorption. This hypothesis is also supported by the current finding of a correlation between slower tablet erosion and longer time to maximum semaglutide plasma concentration.

In the current study, CTE in the stomach took approximately 60‐90 minutes from the time of dosing. Another study showed that the presence of food in the stomach substantially limited the absorption of oral semaglutide. 20 Furthermore, clinically relevant semaglutide exposure was achieved after dosing in the fasting state with a postdose fasting period of only 30 minutes, 21 leading to the recommendation that patients can have a meal from 30 minutes after oral semaglutide dosing, that is, up to 1 hour before tablet erosion is complete. This apparent discrepancy may be explained by the findings of the present study. It was shown that 50% of CTE was achieved within 27‐29 minutes, suggesting that the first 30 minutes after dosing constitutes an important window for absorption of oral semaglutide. Dosing of oral semaglutide in the fasting state with a postdose fasting period of ≥30 minutes has been used in phase 2 and phase 3 trials with oral semaglutide, demonstrating significant reductions in glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c, up to 1.4%) and body weight (up to 4.4 kg), with better glycemic control than with all oral glucose‐lowering therapies tested, including sitagliptin and empagliflozin, and efficacy at least as good as existing GLP‐1 receptor agonists such as liraglutide. 12 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 These dosing conditions are also part of the label for oral semaglutide. 26

The current result of greater semaglutide plasma exposure when the oral semaglutide tablet was given with 50 versus 240 mL water is in accordance with findings from a previous study with the hormone peptide salmon calcitonin in an oral formulation with another absorption enhancer, 5‐CNAC. 15 In that study, plasma exposure of salmon calcitonin was 2‐ to 3‐fold higher when administered with 50 versus 200 mL of water. 15 In the present study, plasma exposure of the absorption enhancer SNAC was lower with administration of 50 mL water, particularly early after dosing (Figure 6 and Supplemental Figure S2), presumably because of slower tablet erosion and consequently slower release of SNAC molecules from the tablet when administered with 50 mL of water. The lower SNAC absorption when oral semaglutide was administered with 50 mL water raises the possibility that at least to a certain extent, higher availability of SNAC remaining in the stomach for a longer period may facilitate semaglutide absorption. Animal data suggest that SNAC promotes absorption of semaglutide in a concentration‐dependent manner relying on the spatial proximity of semaglutide and SNAC. 11 Thus, higher local concentrations of both semaglutide and SNAC in the gastric environment, as expected with a lower water volume taken with dosing, may also have facilitated SNAC‐mediated absorption of semaglutide.

The current study showed a similar esophageal transit time of 1.8 seconds independent of water volume, and no subjects experienced esophageal stasis, as defined by a transit time > 20 seconds. Thus, even when the oral semaglutide tablet was administered with as little as 50 mL water, the tablet passed freely and rapidly through the esophagus. Still, to improve patient convenience, it would be desirable to allow for more than 50 mL water to be taken with the oral semaglutide tablet. It is therefore reassuring that a recent study assessing semaglutide exposure after different dosing conditions demonstrated no difference in semaglutide exposure between water volumes of 50 and 120 mL administered with the tablet. 21 Taken together, the findings from both studies indicate that oral semaglutide should be administered with up to 120 mL water, which is the guidance used in the phase 2 and phase 3 trials with oral semaglutide 12 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 and is part of the label for oral semaglutide. 26

Overall, the safety profile of oral semaglutide in the present study was as expected for the GLP‐1 receptor agonist drug class. The relatively high frequency of headache can most likely be ascribed to the prolonged fasting and the many experimental procedures performed. The frequency of reported gastrointestinal AEs should be viewed in light of the single dose of 10 mg oral semaglutide administered. As is also recommended for other GLP‐1 receptor agonists to mitigate the occurrence of gastrointestinal AEs, 27 the approved dosing regimen for oral semaglutide includes a gradual increase in dose over the first weeks of treatment, with a starting dose of 3 mg oral semaglutide. 26 Thus, the oral semaglutide dose in the present trial was substantially higher than the starting dose for oral semaglutide in clinical practice. The bioavailability of oral semaglutide in dogs of 1%‐2% implies that approximately 98% of the administered drug is not absorbed and thereby could conceivably still contribute to high concentrations of semaglutide in the stomach lumen. However, it is important to bear in mind that given the peptide character of semaglutide, any molecules released from the tablet are exposed to rapid enzymatic degradation if not readily absorbed.

A strength of the present study was the use of scintigraphic imaging to follow the movement of the oral semaglutide tablet through the gastrointestinal tract in a fully noninvasive manner. Scintigraphy is considered the gold standard to investigate the disintegration and dissolution process of a solid oral dosage form in humans. Scintigraphy allows subjects to be in a standing or sitting position during measurements, which is in contrast with, for example, magnetic marker monitoring, in which the stationary sensoring systems necessitate a restrictive setup with subjects in a supine position. 28 Importantly, neither the semaglutide nor the SNAC molecules were radioactively labeled. Instead, the oral semaglutide tablets contained 111In‐labeled ion‐exchange resin, such that the signal detected on the scintigraphic images reflects the position of the tablet core and released tablet particles rather than the flux of semaglutide and SNAC molecules. Still, in vitro assessments demonstrated that the addition of the radiolabel had no adverse impact on the performance of the formulation and that the radiolabel was a suitable marker for tablet performance. Another potential limitation was that the present study was a single‐dose study and thus not reflecting the once‐daily dosing regimen for oral semaglutide, with which steady‐state exposure of semaglutide will be reached after 4‐5 weeks of once‐daily dosing because of its very long half‐life of ∼1 week. The half‐life of ∼1 week for oral semaglutide combined with the washout period of 3‐5 weeks between the first and second dosing visits could at least theoretically have led to a minor carryover effect. However, as the predose semaglutide concentration in plasma was below the LLOQ in all subjects at both dosing visits (data not shown), any carryover effect could be excluded. In the current study, oral semaglutide was administered to subjects while they were in an upright position. Therefore, the current results may not entirely translate to the situation in which subjects take the oral semaglutide tablet while lying in bed. However, in the PIONEER phase 3 program, there was no requirement of standing upright, and oral semaglutide demonstrated significant reductions in HbA1c and body weight with better glycemic control than with sitagliptin and empagliflozin and efficacy at least as good as liraglutide. 23 , 24 , 25

Conclusions

In the present pharmacoscintigraphic study in healthy male subjects, complete oral semaglutide tablet erosion occurred in the stomach irrespective of water volume administered with dosing. Slower tablet erosion in the stomach, as seen when administering the tablet with 50 versus 240 mL water, resulted in higher semaglutide plasma exposure. The current results are in accordance with systemic absorption of oral semaglutide from the stomach and, furthermore, show that the extent of semaglutide exposure depends on the volume of water taken with the oral semaglutide tablet.

Conflicts of Interest

Tine A. Bækdal, Morten Donsmark, and Flemming L. Søndergaard are employees and shareholders of Novo Nordisk A/S. Marie‐Louise Hartoft‐Nielsen was an employee of Novo Nordisk A/S at the time of conduct of the trial and preparation of this article and is a shareholder of Novo Nordisk A/S. Alyson Connor declares no conflicts of interest. Medical writing support was provided by Carsten Roepstorff, PhD, CR Pharma Consult, Copenhagen, Denmark and was funded by Novo Nordisk.

Funding

This study was funded by Novo Nordisk.

Data Sharing

Individual participant data will be shared in data sets in a deidentified/anonymized format. Data sets from Novo Nordisk‐sponsored clinical research completed after 2001 for product indications approved in both the European Union and United States are shared. Study protocol and redacted clinical study report (CSR) will be available according to Novo Nordisk data‐sharing commitments. The data will be available permanently after research completion and approval of product and product use in both the European Union and the United States, with no end date. Data will be shared with bona fide researchers submitting a research proposal requesting access to data for use as approved by the independent review board (IRB) according to the IRB charter (see novonordisk‐trials.com). Access request proposal form and the access criteria can be found at novonordisk‐trials.com. The data will be made available on a specialized SAS data platform.

Supporting information

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joanne Collier, MBChB, FFPM, Quotient Sciences, Nottingham, UK, for being the principal investigator of the trial.

References

- 1. Meier JJ. GLP‐1 receptor agonists for individualized treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(12):728‐742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tomlinson B, Hu M, Zhang Y, Chan P, Liu ZM. An overview of new GLP‐1 receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25(2):145‐158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lau J, Bloch P, Schäffer L, et al. Discovery of the once‐weekly glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) analogue semaglutide. J Med Chem. 2015;58(18):7370‐7380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jensen L, Helleberg H, Roffel A, et al. Absorption, metabolism and excretion of the GLP‐1 analogue semaglutide in humans and nonclinical species. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2017;104:31‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sorli C, Harashima SI, Tsoukas GM, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide monotherapy versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 1): a double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group, multinational, multicentre phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(4):251‐260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aroda VR, Bain SC, Cariou B, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide versus once‐daily insulin glargine as add‐on to metformin (with or without sulfonylureas) in insulin‐naive patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 4): a randomised, open‐label, parallel‐group, multicentre, multinational, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(5):355‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahrén B, Masmiquel L, Kumar H, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide versus once‐daily sitagliptin as an add‐on to metformin, thiazolidinediones, or both, in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 2): a 56‐week, double‐blind, phase 3a, randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(5):341‐354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1834‐1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mustata G, Dinh SM. Approaches to oral drug delivery for challenging molecules. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2006;23(2):111‐135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Muheem A, Shakeel F, Jahangir MA, et al. A review on the strategies for oral delivery of proteins and peptides and their clinical perspectives. Saudi Pharm J. 2016;24(4):413‐428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buckley ST, Bækdal TA, Vegge A, et al. Transcellular stomach absorption of a derivatized glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(467):eaar7047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davies M, Pieber TR, Hartoft‐Nielsen M‐L, Hansen OKH, Jabbour S, Rosenstock J. Effect of oral semaglutide compared with placebo and subcutaneous semaglutide on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(15):1460‐1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilding IR, Coupe AJ, Davis SS. The role of gamma‐scintigraphy in oral drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46(1‐3):103‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jain S, Dani P, Sharma RK. Pharmacoscintigraphy: a blazing trail for the evaluation of new drugs and delivery systems. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2009;26(4):373‐426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karsdal MA, Byrjalsen I, Riis BJ, Christiansen C. Optimizing bioavailability of oral administration of small peptides through pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters: the effect of water and timing of meal intake on oral delivery of salmon calcitonin. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2008;8:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lobo ED, Argentine MD, Sperry DC, et al. Optimization of LY545694 tosylate controlled release tablets through pharmacoscintigraphy. Pharm Res. 2012;29(10):2912‐2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baekdal TA, Thomsen M, Kupčová V, Hansen CW, Anderson TW. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of oral semaglutide in subjects with hepatic impairment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;58(10):1314‐1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. American Diabetes Association. Defining and reporting hypoglycaemia in diabetes: a report from the American Diabetes Association Workgroup on Hypoglycaemia. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(5):1245‐1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Castelli MC, Connor A, Wilding I, Riley MG. A gamma scintigraphic clinical study of the absorption of Insulin co‐formulated with Eligen® absorption enhancer 4‐CNAB. FASEB J. 2011;25(Suppl 1):lb394 (Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maarbjerg SJ, Borregaard J, Breitschaft A, Donsmark M, Søndergaard FL. Evaluation of the effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of oral semaglutide. Diabetes. 2017;66(Suppl 1):A321 (Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bækdal TA, Borregaard J, Donsmark M, Breitschaft A, Søndergaard FL. Evaluation of the effects of water volume with dosing and post‐dose fasting period on pharmacokinetics of oral semaglutide. Diabetes. 2017;66(Suppl 1):A315 (Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aroda VR, Rosenstock J, Terauchi Y, et al. PIONEER 1: Randomized clinical trial of the efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide monotherapy in comparison with placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(9):1724‐1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rodbard HW, Rosenstock J, Canani LH, et al. Oral semaglutide versus empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled on metformin: the PIONEER 2 trial. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(12):2272‐2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosenstock J, Allison D, Birkenfeld AL, et al. Effect of additional oral semaglutide vs sitagliptin on glycated hemoglobin in adults with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled with metformin alone or with sulfonylurea: the PIONEER 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(15):1466‐1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pratley R, Amod A, Hoff ST, et al. Oral semaglutide versus subcutaneous liraglutide and placebo in type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 4): a randomised, double‐blind, phase 3a trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):39‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cowart K. Oral semaglutide: First‐in‐class oral GLP‐1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54(5):478‐485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Romera I, Cebrián‐Cuenca A, Álvarez‐Guisasola F, Gomez‐Peralta F, Reviriego J. A review of practical issues on the use of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists for the management of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10(1):5‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Biller S, Baumgarten D, Haueisen J. Magnetic marker monitoring: a novel approach for magnetic marker design. In: Bamidis PD, Pallikarakis N, eds. XII Mediterranean Conference on Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing 2010. IFMBE Proceedings, volume 29, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information