Key Points

Question

Are refractive outcomes similar between immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery (ISBCS), short-interval (1-14 days) delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery (DSBCS-14), and long-interval (15-90 days) delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery (DSBCS-90)?

Findings

In this cohort study of 1 824 196 patients from the Intelligent Research in Sight Registry, uncorrected and best-corrected visual acuities were lower for patients undergoing ISBCS by 2.79 and 1.64 letters, respectively, and higher for patients undergoing DSBCS-14 by 0.41 and 0.89 letters, respectively, compared with those undergoing DSBCS-90.

Meaning

This study found that ISBCS was associated with worse outcomes than DSBCS, although the small but statistically significant differences may not be clinically relevant.

Abstract

Importance

Approximately 2 million cataract operations are performed annually in the US, and patterns of cataract surgery delivery are changing to meet the increasing demand. Therefore, a comparative analysis of visual acuity outcomes after immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery (ISBCS) vs delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery (DSBCS) is important for informing future best practices.

Objective

To compare refractive outcomes of patients who underwent ISBCS, short-interval (1-14 days between operations) DSBCS (DSBCS-14), and long-interval (15-90 days) DSBCS (DSBCS-90) procedures.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study used population-based data from the American Academy of Ophthalmology Intelligent Research in Sight (IRIS) Registry. A total of 1 824 196 IRIS Registry participants with bilateral visual acuity measurements who underwent bilateral cataract surgery were assessed.

Exposures

Participants were divided into 3 groups (DSBCS-90, DSBCS-14, and ISBCS groups) based on the timing of the second eye surgery. Univariable and multivariable linear regression models were used to analyze the refractive outcomes of the first and second surgery eye.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Mean postoperative uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) and best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) after cataract surgery.

Results

This study analyzed data from 1 824 196 patients undergoing bilateral cataract surgery (mean [SD] age for those <87 years, 70.03 [7.77]; 684 916 [37.5%] male). Compared with the DSBCS-90 group, after age, self-reported race, insurance status, history of age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma were controlled for, the UCVA of the first surgical eye was higher by 0.41 (95% CI, 0.36-0.45; P < .001) letters, and the BCVA was higher by 0.89 (95% CI, 0.86-0.92; P < .001) letters in the DSBCS-14 group, whereas in the ISBCS group, the UCVA was lower by 2.79 (95% CI, −2.95 to −2.63; P < .001) letters and the BCVA by 1.64 (95% CI, −1.74 to −1.53; P < .001) letters. Similarly, compared with the DSBCS-90 group for the second eye, in the DSBCS-14 group, the UCVA was higher by 0.79 (95% CI, 0.74-0.83; P < .001) letters and the BCVA by 0.48 (95% CI, 0.45-0.51; P < .001) letters, whereas in the ISBCS group, the UCVA was lower by −1.67 (95% CI, −1.83 to −1.51; P < .001) letters and the BCVA by −1.88 (95% CI, −1.98 to −1.78; P < .001) letters.

Conclusions and Relevance

The results of this cohort study of patients in the IRIS Registry suggest that compared with DSBCS-14 or DSBCS-90, ISBCS is associated with worse visual outcomes, which may or may not be clinically relevant, depending on patients’ additional risk factors. Nonrandom surgery group assignment, confounding factors, and large sample size could account for the small but statistically significant differences noted. Further studies are warranted to determine whether these factors should be considered clinically relevant when counseling patients before cataract surgery.

This cohort study compares refractive outcomes of patients undergoing immediate and delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery.

Introduction

Cataract is the leading cause of visual impairment in the US,1,2 affecting an estimated 24 million people,3 which is expected to double by 2050.3 Approximately 2 million cataract operations are performed annually in the US,4 and patterns of cataract surgery delivery are changing to meet the increasing demand. Thus, evaluating these trends is important for informing future best practices.

In the US, cataract surgery is usually performed with 1 to 2 weeks or more between eyes. Conflicting literature exists about whether visual outcomes are better with delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery (DSBCS) or immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery (ISBCS), in which the surgeon operates on both eyes on the same day as separate procedures.5,6,7 DSBCS has been preferred historically because it allows for adjustment of the intraocular lens power in the second eye in case of refractive surprise and provides time to monitor for endophthalmitis or other complications that can cause severe vision loss.8 ISBCS is the preferred approach in several countries outside the US,9 but on the 2018 American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery survey, only 9% of respondents reported performing ISBCS sometimes or often.10 Potential advantages of ISBCS include immediately improved bilateral vision, fewer follow-up visits, improved efficiency, and potential for reduced costs. In addition, studies11,12 from countries where ISBCS is routine suggest that risk of bilateral endophthalmitis is low with the use of intracameral antibiotics and strict aseptic separation between operations.

The goal of cataract surgery is to improve vision and quality of life.13 In recent years, ISBCS has gained favor among US ophthalmologists. However, the question of whether unexpected refractive outcome occurs more often with ISBCS remains unanswered and is likely an important consideration. Furthermore, knowledge of any additional factors associated with worse visual outcome after cataract surgery is critical for practitioners and patients who need to be counseled appropriately.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology Intelligent Research in Sight (IRIS) Registry14 includes electronic health record data from more than 50 million unique patient visits, including demographic and clinical information. We aimed to analyze this large data set to evaluate any potential disparity in refractive outcomes among ISBCS, short-interval (within 1-14 days between 2 operations) DSBCS (DSBCS-14), and long-interval (15-90 days apart) DSBCS (DSBCS-90). We also aimed to identify any factors associated with worse visual outcome.

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.15 Given the use of deidentified patient data, this study was exempted from review by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. Data collection and aggregation of the IRIS Registry database methods have previously been described.16,17 Version 2019_10_22 of the IRIS Registry was used for this analysis, which was last modified on April 15, 2020. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Study Patient Population

Patients in the IRIS Registry with a history of bilateral cataract surgery were included. Cataract surgery was defined using Current Procedural Terminology code 66984. DSBCS-90 was defined as second eye surgery that occurred between 15 and 90 days after the first eye surgery. DSBCS-14 was defined as second eye procedure that occurred within 1 and 14 days after the first eye procedure. ISBCS was defined as both eye procedures occurring on the same date. For ISBCS, we randomly chose either eye to be coded as the first surgery eye. For a secondary analysis, we assigned the worse eye as the first eye and the better eye as the second eye in the ISBCS group. Three surgery groups were evaluated to assess whether DSBCS outcomes with a shorter interval (within 2 weeks) between eyes differed from outcomes with a longer interval. Further details of the exclusion criteria and extracted variables are discussed in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline demographic features and the outcome measures were summarized by surgery group with means and percentages. The primary outcomes of interest were postsurgical uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) and best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in logMAR. Means were also reported in Snellen equivalent. The proportion of participants achieving 20/20 visual acuity (VA) after surgery was reported as the percentage of the number of participants with available postoperative VA measurements available. Single and multivariable linear regression was used to analyze patient characteristics for association with VA outcomes for first and second surgery eye. Cases for which decade of life, presurgical, and postsurgical VA were reported were used in the regression models, and separate models were fit for each eye. Within the IRIS Registry, VA is reported in Snellen, but corresponding logMAR values are provided. We used logMAR values for our analyses, but outcomes were converted from logMAR to corresponding Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study equivalent letters for ease of interpretation. The independent variables evaluated in the multivariable regression model included age decade at first surgery; sex; self-reported race; insurance; history of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy (DR), or glaucoma in the surgery eye; and surgical intervention group (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

Multivariable modeling was performed again, assigning the eye with worse presurgery VA as the first surgery eye and the eye with best presurgery VA as the second eye for the ISBCS group to check whether outcome differences were caused by random eye assignment. This procedure was motivated by the fact that surgery tended to occur first on the eye with worse VA. An analysis of surgeon volume by surgery group was performed and added to the models (eMethods in Supplement 1). A 2-sided P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with R statistical software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

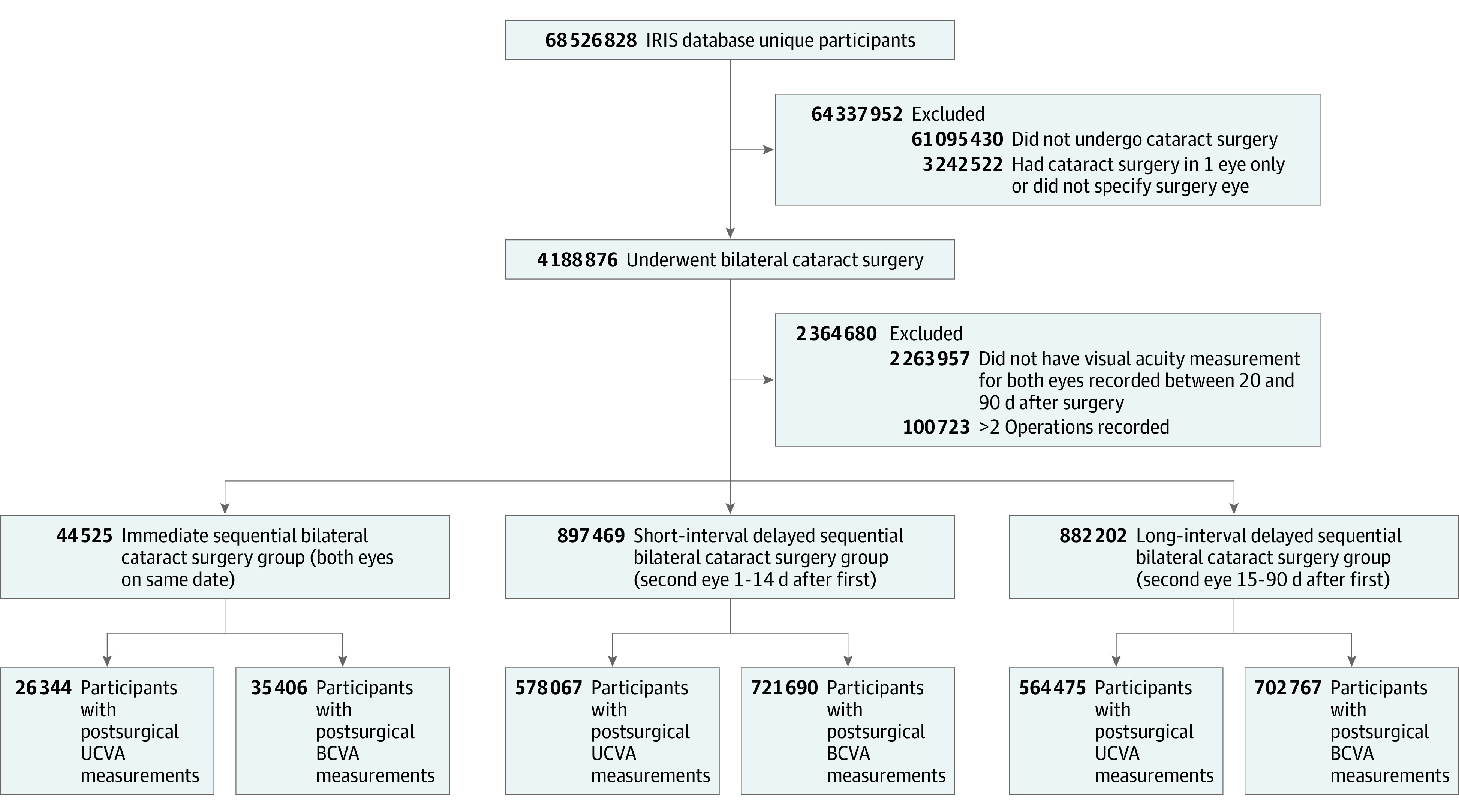

We analyzed data from 1 824 196 patients undergoing bilateral cataract surgery (mean [SD] age for those <87 years, 70.03 [7.77]; 684 916 [37.5%] male). A total of 44 525 patients underwent ISBCS, 897 469 patients underwent DSBCS-14, and 882 202 underwent DSBCS-90 (Figure 1). There was a mean interval of 11.4 days between the first and second eye procedures in the DSBCS-14 group and a mean interval of 34.6 days in the DSBCS-90 group.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Study Participants.

BCVA indicates best-corrected visual acuity; IRIS, Intelligent Research in Sight; UCVA, uncorrected visual acuity.

Patient demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1. All 3 groups had similar rates of AMD (ISBCS: 100 048 [11.3] in the first eye and 101 770 [11.5] in the second eye; DSBCS-14: 100 800 [11.2] in the first eye and 101 566 [11.3] in the second eye; DSBCS-90: 4516 [10.1] in the first eye and 4561 [10.2] in the second eye), DR (ISBCS: 37 782 [4.3] in the first eye and 38 705 [4.4] in the second eye; DSBCS-14: 32 993 [3.7] in the first eye and 33 377 [3.7] in the second eye; DSBCS-90: 2105 [4.7] in the first eye and 2100 [4.7] in the second eye), and glaucoma (ISBCS: 175 901 [19.9] in the first eye and 178 440 [20.2] in the second eye; DSBCS-14: 169 475 [18.9] in the first eye and 170 778 [19.0] in the second eye; DSBCS-90: 8625 [19.4] in the first eye and 8649 [19.4] in the second eye).

Table 1. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics by Surgical Groupa.

| Characteristic | DSBCS-90 (n = 882 202) | DSBCS-14 (n = 897 469) | ISBCS (n = 44 525) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 554 426 (62.8) | 554 205 (61.8) | 26 796 (60.28) |

| Male | 325 434 (36.9) | 341 805 (38.1) | 17 677 (39.7) |

| Not reported | 2342 (0.3) | 1459 (0.2) | 52 (0.1) |

| Race | |||

| White | 676 152 (76.6) | 709 931 (79.1) | 33 435 (75.19) |

| Black or African American | 54 783 (6.2) | 42 715 (4.8) | 2901 (6.5) |

| Asian | 19 993 (2.3) | 15 166 (1.7) | 1192 (2.7) |

| Otherb | 10 190 (1.2) | 9134 (1.0) | 435 (1.0) |

| Unknown | 121 084 (13.7) | 120 523 (13.4) | 6562 (14.7) |

| Age at surgery for those <87 y | 818 087 (92.7) | 847 111 (94.4) | 42 028 (94.4) |

| First surgery, mean (SD) | 70.31 (7.7) | 69.8 (7.8) | 69.4 (8.9) |

| Second surgery, mean (SD) | 70.39 (7.7) | 69.81 (7.8) | |

| ≥87 y At first surgery | 63 013 (7.1) | 49 720 (5.5) | 2454 (5.5) |

| Missing date of birth | 1102 (0.1) | 638 (0.1) | 43 (0.1) |

| Type of insurance | |||

| Medicare | 326 475 (37.0) | 324 408 (36.1) | 14 235 (32.0) |

| Commercial | 282 349 (32.0) | 293 691 (32.7) | 13 231 (29.7) |

| Medicaid | 9489 (1.1) | 7711 (0.9) | 993 (2.2) |

| Other | 263 889 (29.9) | 271 659 (30.3) | 16 066 (36.18) |

| Right laterality of first surgery | 484 422 (54.9) | 502 512 (56.0) | 22 265 (50.0) |

| Prior diagnoses | |||

| Age-related macular degeneration | |||

| First eye | 100 048 (11.3) | 100 800 (11.2) | 4516 (10.1) |

| Second eye | 101 770 (11.5) | 101 566 (11.3) | 4561 (10.2) |

| Diabetic retinopathy | |||

| First eye | 37 782 (4.3) | 32 993 (3.7) | 2105 (4.7) |

| Second eye | 38 705 (4.4) | 33 377 (3.7) | 2100 (4.7) |

| Glaucoma | |||

| First eye | 175 901 (19.9) | 169 475 (18.9) | 8625 (19.4) |

| Second eye | 178 440 (20.2) | 170 778 (19.0) | 8649 (19.4) |

| Time between operations, mean (SD), d | 34.65 (16.57) | 11.44 (3.46) | 0 |

| Presurgical BCVA | |||

| First eye | |||

| No. (%) | 84 9219 (96.3) | 867 553 (96.7) | 43 089 (96.8) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.352 (0.374) | 0.331 (0.362) | 0.263 (0.367) |

| Snellen equivalent | 20/45 | 20/43 | 20/37 |

| Second eye | |||

| No. (%) | 863 395 (97.9) | 876 113 (97.6) | 43 086 (96.8) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.252 (0.292) | 0.247 (0.294) | 0.264 (0.377) |

| Snellen equivalent | 20/36 | 20/35 | 20/37 |

Abbreviations: BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; DSBCS-14, delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery with 1- to 14-day interval; DSBCS-90, delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery with 15- to 90-day interval; IRIS, Intelligent Research in Sight; ISBCS, immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Other race indicates that the individuals were reported as other in the IRIS Registry.

The ISBCS, DSBCS-14, and DSBCS-90 groups had similar baseline VA by worse-seeing eye (20/48 in the ISBCS group, 20/50 in the DSBCS-14 group, and 20/51 in the DSBCS-90 group), whereas the VA of the better-seeing eye in the ISBCS group was higher (20/28) compared with the DSBCS-14 (20/30) and DSBCS-90 (20/31) groups (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

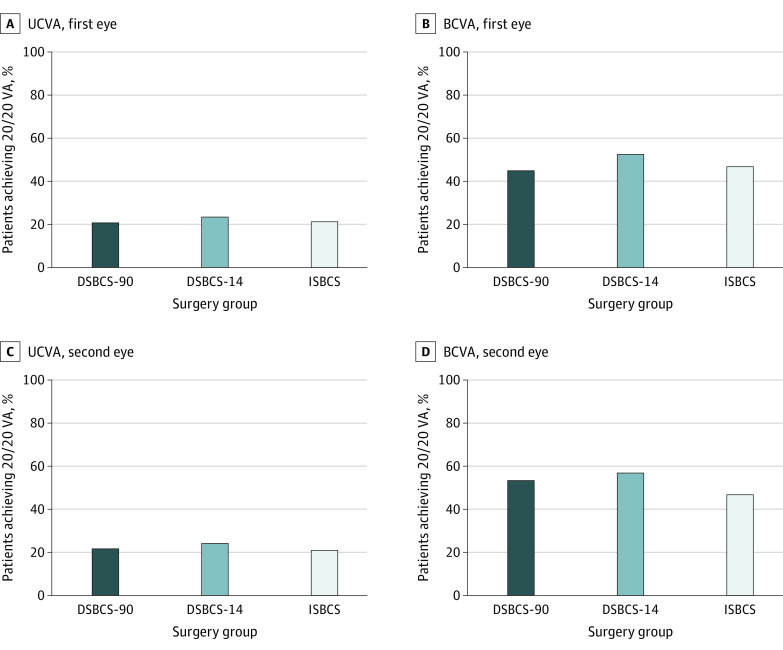

Postsurgical VA

Postoperative UCVA and BCVA are reported in Table 2. The ISBCS group had similar mean VA in their first and second surgery eye, averaging 20/38 for UCVA and 20/28 for BCVA. For the ISBCS group, 21.2% of patients achieved uncorrected 20/20 VA in the first surgery eye and 21.0% achieved uncorrected 20/20 in the second surgery eye. For BCVA, 46.8% achieved 20/20 VA in the first surgery eye and 46.8% achieved 20/20 VA in the second surgery eye (Figure 2).

Table 2. Postsurgical Visual Acuity by Surgical Group.

| Outcome | UCVA | BCVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSBCS-90 (n = 882 202) | DSBCS-14 (n = 897 469) | ISBCS (n = 44 525) | DSBCS-90 (n = 882 202) | DSBCS-14 (n = 897 469) | ISBCS (n = 44 525) | |

| Total No. (%) | 564 475 (64.0) | 578 067 (64.4) | 26 344 (59.2) | 702 767 (79.7) | 721 690 (80.4) | 35 406 (79.5) |

| First eye | ||||||

| Mean (SD) VA | 0.241 (0.274) | 0.226 (0.265) | 0.278 (0.369) | 0.127 (0.215) | 0.101 (0.194) | 0.144 (0.299) |

| Snellen equivalent | 20/35 | 20/34 | 20/38 | 20/27 | 20/25 | 20/28 |

| DSBCS-90 vs DSBCS-14 VA (95% CI) | −0.015 (−0.016 to −0.014) | −0.025 (−0.026 to −0.025) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| DSBCS-90 vs ISBCS VA (95% CI) | 0.036 (0.033 to 0.040) | 0.017 (0.015 to 0.020) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| DSBCS-14 vs ISBCS VA (95% CI) | 0.051 (0.048 to 0.055) | 0.043 (0.040 to 0.045) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| Achieved 20/20 VA, No. (%) | 116 931 (20.7) | 135 085 (23.4) | 5585 (21.2) | 315 613 (44.9) | 378 763 (52.5) | 16 580 (46.8) |

| DSBCS-90 vs DSBCS-14, % (95% CI) | −2.7 (−2.8 to −2.5) | −7.6 (−7.7 to −7.4) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| DSBCS-90 vs ISBCS, % (95% CI) | −0.5 (−1.0 to 0.0) | −1.9 (−2.5 to −1.4) | ||||

| P value | .06 | <.001 | ||||

| DSBCS-14 vs ISBCS, % (95% CI) | 2.2 (1.7 to 2.7) | 5.7 (5.1 to 6.2) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| Second eye | ||||||

| Mean (SD) VA | 0.239 (0.280) | 0.220 (0.261) | 0.275 (0.368) | 0.100 (0.205) | 0.087 (0.183) | 0.142 (0.295) |

| Snellen equivalent | 20/35 | 20/33 | 20/38 | 20/25 | 20/24 | 20/28 |

| DSBCS-90 vs DSBCS-14 VA (95% CI) | −0.019 (−0.020 to −0.018) | −0.013 (−0.014 to −0.013) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| DSBCS-90 vs ISBCS VA (95% CI) | 0.036 (0.032 to 0.039) | 0.042 (0.040 to 0.044) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| DSBCS-14 vs ISBCS VA (95% CI) | 0.054 (0.051 to 0.058) | 0.055 (0.053 to 0.057) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| Achieved 20/20 VA, No. (%) | 122 215 (21.7) | 139 952 (24.2) | 5527 (21.0) | 375 337 (53.4) | 410 598 (56.9) | 16 587 (46.8) |

| DSBCS-90 vs DSBCS-14, % (95% CI) | −2.6 (−2.7 to −2.4) | −3.5 (−3.6 to −3.3) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| DSBCS-90 vs ISBCS, % (95% CI) | 0.7 (0.2 to 1.2) | 6.6 (6.0 to 7.1) | ||||

| P value | .01 | <.001 | ||||

| DSBCS-14 vs ISBCS, % (95% CI) | 3.2 (2.7 to 3.7) | 10.0 (9.5 to 10.6) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

Abbreviations: BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; DSBCS-14, delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery with 1- to 14-day interval; DSBCS-90, delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery with 15- to 90-day interval; ISBCS, immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery; UCVA, uncorrected visual acuity.

Figure 2. Percentage of Study Participants Achieving Postoperative 20/20 Visual Acuity (VA).

The percentage of participants achieving 20/20 VA after surgery for the first and second surgery eye was calculated from the number of participants with postoperative visual acuity reported by best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA). DSBCS-14, indicates delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery at 1 to 14 days; DSBCS-90, delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery at 15 to 90 days; and ISBCS, immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery.

In the DSBCS-90 group, the mean postoperative UCVA was 20/35 for both eyes. The proportion of patients in the DSBCS-90 group achieving 20/20 UCVA was 0.5% less than in the ISBCS group (95% CI, 0.0% to −1.0%; P = .06) in the first eye and 0.7% more than in the ISBCS group (95% CI, 0.2%-1.2%; P = .01) in the second eye. The mean BCVA for the DSBCS-90 group was 20/27 in the first eye and 20/25 in the second surgery eye, and the proportion of patients in the DSBCS-90 group achieving 20/20 BCVA was 1.9% less than in the ISBCS group (95% CI, −1.4% to −2.5%; P < .001) in the first eye and 6.6% more than in the ISBCS group (95% CI, 6.0%-7.1%; P < .001) in the second eye (Figure 2 and Table 2).

Patients in the DSBCS-14 group had the best mean UCVA and BCVA in both eyes. Both UCVA and BCVA were better in the second surgery eye (20/33 UCVA and 20/24 BCVA) compared with the first surgery eye (20/34 UCVA and 20/25 BCVA). The proportion of patients in the DSBCS-14 group achieving 20/20 UCVA was 2.2% more than in the ISBCS group (95% CI, 1.7%-2.7%; P < .001) in the first eye and 3.2% more than in the ISBCS group (95% CI, 2.7%-3.7%; P < .001) in the second eye. For BCVA, 5.7% more of the DSBCS-14 group achieved 20/20 VA than in the ICBCS group (95% CI, 5.1%-6.2%; P < .001) in the first eye and 10.0% more than in the ISBCS group (95% CI, 9.5%-10.6%; P < .001) in the second eye (Figure 2).

Multivariable Regression Analyses

Univariate analysis results are reported in the eResults and eTable 3 in Supplement 1. Older age was associated with slightly worse UCVA (mean [SD] of 1.01 [0.03] fewer letters in the first surgery eye and 0.75 [0.03] fewer in the second eye) and BCVA (mean [SD] of 0.93 [0.02] fewer letters in the first surgery eye and 0.67 [0.02] fewer in the second eye). Diabetic retinopathy was independently associated with worse outcomes (mean [SD] of 4.29 [0.13] fewer letters for UCVA and 4.47 [0.09] fewer letters for BCVA in the first eye and 3.51 [0.12] fewer letters for UCVA and 3.92 [0.08] fewer letters for BCVA in the second eye), and less difference was associated with AMD and glaucoma. Asian patients had worse VA (mean [SD] of 1.08 [0.17] [first eye] and 1.24 [0.17] [second eye] fewer letters for UCVA and 0.90 [0.12] [first eye] and 0.80 [0.11] [second eye] fewer letters for BCVA) compared with White and Black/African American patients (mean [SD] of 0.46 [0.11] [first eye] and 0.23 [0.11] [second eye] fewer letters for UCVA, and 1.10 [0.07] [first eye] and 0.97 [0.07] [second eye] fewer letters for BCVA). Compared with Medicare beneficiaries, patients with Medicaid had a worse mean (SD) UCVA by 1.49 (0.23) letters in the first eye and 1.20 (0.23) letters in the second eye and worse mean (SD) BCVA by 1.66 (0.17) letters in the first eye and 1.29 (0.15) letters in the second eye (Table 3).

Table 3. Multivariable Linear Model Results for Postoperative Visual Acuity.

| Characteristic | UCVA | BCVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: first surgery eye | Model 2: second surgery eye | Model 3: first surgery eye | Model 4: second surgery eye | |||||

| Change in letters (95% CI) | P value | Change in letters (95% CI) | P value | Change in letters (95% CI) | P value | Change in letters (95% CI) | P value | |

| Decade of life | −1.01 (−1.04 to −0.98) | <.001 | −0.75 (−0.78 to −0.72) | <.001 | −0.93 (−0.95 to −0.91) | <.001 | −0.67 (−0.69 to −0.65) | <.001 |

| Sex (referent: female) | ||||||||

| Male | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.98) | <.001 | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.03) | <.001 | 0.15 (0.11 to 0.18) | <.001 | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.09) | <.001 |

| Not reported | −0.48 (−0.95 to 0) | .05 | −0.16 (−0.64 to 0.31) | .50 | 0.69 (0.36 to 1.02) | <.001 | 0.28 (−0.02 to 0.59) | .07 |

| Race (referent: White) | ||||||||

| Asian | −1.08 (−1.24 to −0.91) | <.001 | −1.24 (−1.41 to −1.08) | <.001 | −0.9 (−1.02 to −0.79) | <.001 | −0.8 (−0.91 to −0.69) | <.001 |

| Black or African American | −0.46 (−0.57 to −0.36) | <.001 | −0.23 (−0.34 to −0.13) | <.001 | −1.1 (−1.17 to −1.03) | <.001 | −0.97 (−1.03 to −0.9) | <.001 |

| Othera | −1.28 (−1.51 to −1.04) | <.001 | −1.08 (−1.31 to −0.85) | <.001 | −1.28 (−1.44 to −1.13) | <.001 | −1.01 (−1.16 to −0.87) | <.001 |

| Unknown | −0.13 (−0.2 to −0.06) | <.001 | −0.13 (−0.19 to −0.06) | <.001 | −0.44 (−0.49 to −0.39) | <.001 | −0.37 (−0.42 to −0.33) | <.001 |

| Insurance (referent: Medicare) | ||||||||

| Commercial | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.13) | .02 | −0.01 (−0.07 to 0.05) | .77 | −0.1 (−0.14 to −0.06) | <.001 | −0.1 (−0.13 to −0.06) | <.001 |

| Medicaid | −1.49 (−1.72 to −1.25) | <.001 | −1.2 (−1.43 to −0.97) | <.001 | −1.66 (−1.83 to −1.5) | <.001 | −1.29 (−1.45 to −1.14) | <.001 |

| Other | 0.26 (0.2 to 0.32) | <.001 | 0.25 (0.19 to 0.31) | <.001 | 0.26 (0.22 to 0.3) | <.001 | 0.16 (0.12 to 0.2) | <.001 |

| Prior diagnosis in surgery eye | ||||||||

| AMD | −3.02 (−3.1 to −2.95) | <.001 | −2.32 (−2.39 to −2.24) | <.001 | −2.76 (−2.81 to −2.71) | <.001 | −2.11 (−2.16 to −2.06) | <.001 |

| DR | −4.29 (−4.41 to −4.16) | <.001 | −3.51 (−3.63 to −3.39) | <.001 | −4.47 (−4.55 to −4.38) | <.001 | −3.92 (−4 to −3.84) | <.001 |

| Glaucoma | −1.19 (−1.26 to −1.13) | <.001 | −0.83 (−0.89 to −0.77) | <.001 | −0.99 (−1.03 to −0.95) | <.001 | −0.74 (−0.78 to −0.71) | <.001 |

| Baseline BCVA in surgery eye | 0.2 (0.19 to 0.2) | <.001 | 0.27 (0.27 to 0.27) | <.001 | 0.17 (0.17 to 0.18) | <.001 | 0.25 (0.24 to 0.25) | <.001 |

| Surgery group (referent: DSBCS-90) | ||||||||

| DSBCS-14 | 0.41 (0.36 to 0.45) | <.001 | 0.79 (0.74 to 0.83) | <.001 | 0.89 (0.86 to 0.92) | <.001 | 0.48 (0.45 to 0.51) | <.001 |

| ISBCS | −2.79 (−2.95 to −2.63) | <.001 | −1.67 (−1.83 to −1.51) | <.001 | −1.64 (−1.74 to −1.53) | <.001 | −1.88 (−1.98 to −1.78) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: AMD, age-related macular degeneration; BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; DR, diabetic retinopathy; DSBCS-14, delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery with 1- to 14-day interval; DSBCS-90, delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery with 15- to 90-day interval; IRIS, Intelligent Research in Sight; ISBCS, immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery; UCVA, uncorrected visual acuity.

Other race indicates that the individuals were reported as other in the IRIS Registry.

After age; self-reported race; insurance status; history of AMD, DR, and glaucoma; and surgical intervention group were adjusted for, ISBCS was associated with worse postoperative VA in either eye (UCVA [first eye]: 2.79 [0.16] fewer letters; BCVA [first eye]: 1.64 [0.10] fewer letters; UCVA [second eye]: 1.67 [0.16] fewer letters; BCVA [second eye]: 1.88 [0.10] fewer letters) compared with the DSBCS-90. The DSBCS-14 group had slightly better outcomes (UCVA [first eye]: 0.41 [0.05] more letters; BCVA [first eye]: 0.89 [0.03] more letters; UCVA [second eye]: 0.79 [0.05] more letters; BCVA [second eye]: 0.48 [0.03] more letters) than the DSBCS-90 group (Table 3). These differences persisted when the eye with worse presurgical VA was assigned as the first surgery eye (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Visual acuity outcomes were similar when surgeon volume data were added to the analysis and when we restricted our analyses to best case group, such as for White women younger than 65 years with non-Medicaid insurance with no prior eye disease (eResults and eTables 3, 5, and 6 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

This cohort study analyzed data from 44 525 patients who underwent ISBCS, 897 469 patients who underwent DSBCS-14, and 882 202 patients who underwent DSBCS-90. The study found that the ISBCS group had statistically significantly worse UCVA (2.8 fewer letters in first eyes and 1.7 fewer letters in second eyes) compared with the DSBCS-90 group, despite having better presurgical BCVA. Unexpectedly, the DSBCS-14 group had similar but better VA outcomes that were statistically significant compared with the DSBCS-90 group. Self-reported race other than White, Medicaid coverage, and comorbid eye disease were associated with worse outcome.

Previous studies18,19,20,21 have compared refractive outcomes after ISBCS and DSBCS but were limited by small sample size. One randomized clinical trial in Sweden (n = 88) found that binocular contrast sensitivity and quality of life were greater in the ISBCS group at 2 months compared with the DSBCS group, but these differences disappeared by 4 months.18 A nonrandomized study (n = 220) had similar findings, although the ISBCS group had higher self-reported visual function scores than the DSBCS group.19 Two other randomized clinical trials20,21 reported similar results, with no significant difference in VA between the ISBCS and DSBCS groups 1 month after second eye surgery. Notably, these studies20,21 excluded patients at risk for poor visual outcomes because of factors such as extreme axial length or other sight-threatening diseases, likely reducing the potential for refractive surprises. The current study did not exclude patients with comorbid ophthalmic disease and likely represents real-world scenarios wherein many patients are potential candidates for different surgery groups. Studies22,23,24 have found better visual outcomes for surgeons who perform a higher volume of operations. However, the current results did not change when controlled for each surgeon’s surgical volume, indicating that our outcome differences, albeit small, are likely not associated with outcome differences among surgeons performing a high vs low volume of operations.

Studies have reported VA improvement in the second eye using first eye results, claiming that the prediction error for the first eye could be used to improve second eye outcome.6,7,25 However, it is unclear how often this occurs in a clinical setting. A review26 of 110 patients who underwent ISBCS revealed that only 6 had refractive outcomes that could have been improved by delaying the second surgery. Proponents of ISBCS note that refraction improvements in the second eye are modest except in rare cases, that patients’ eyes may be too different to compare, and/or that recent improvements in biometric technology are well on their way to eliminating any difference in outcomes between ISBCS and DSBCS.27,28,29

In the current analysis, however, the DSBCS-14 and DSBCS-90 groups had small but statistically significantly better outcomes. The proportion who achieved uncorrected 20/20 in the second surgery eye was higher for DSBCS-14 (24.2%) and DSBCS-90 (21.7%) compared with ISBCS (21.0%). These results are consistent with the possibility that the interval between operations in the DSBCS-14 and DSBCS-90 groups may have allowed for adjustments that resulted in better second eye outcome. The current study also found that race, insurance type, and comorbid eye disease were associated with worse outcomes, suggesting that other factors may have influenced visual outcomes among surgery groups.

Race and socioeconomic factors have previously been associated with cataract prevalence, access to care, and severity at time of surgery.30,31,32,33,34 Few US studies have reported visual outcome difference by race and socioeconomic status,35 although worse outcomes are associated with poverty in low- and middle-income countries.36 Unexpectedly, this study found statistically significant differences in outcomes in patients with Medicaid coverage and patients of races other than White even after other confounders were controlled for. For example, Asian and African American patients performed 0.5 to 1.2 letters worse than White patients of the same age, sex, and insurance status and with equivalent comorbid eye diseases. This small difference may not be clinically meaningful but could be helpful when counseling patients preoperatively, especially those with risks for worse outcome. In the current study, an Asian patient with DR and Medicaid coverage would see 5 fewer letters (approximately 1 line in Snellen) than a White patient with Medicare coverage and without DR.

Several explanations exist for these findings. Patients with late-stage AMD or severe DR may have limited gains in visual function with cataract surgery.37,38,39,40 Studies41,42 have found a higher prevalence of myopia in Asian American populations, and high myopia is associated with worse prognosis after cataract surgery.43 It is possible that some patients did not receive follow-up care postoperatively, and so corresponding BCVA was not available. Members of minority groups and those with Medicaid may have limited access to care.44 Blindness secondary to untreated cataract was 4 times more common in African American patients than in White patients in a Baltimore community study.45 In addition, a study30 of more than 1 million Medicare beneficiaries found that Black patients were 1.9 times more likely to have complex cataract surgery, which is associated with worse outcomes. The current study found a similar outcome discrepancy in African American patients even though we included only routine cataract operations.

The current study found worse outcomes associated with ocular comorbidities similar to previous studies.37,38,39,40,46 Patients with AMD have less postoperative improvement compared with those without retinal disease,38,40 and patients with glaucoma are more likely to have refractive surprise after cataract surgery.46 Severe DR and poor preoperative VA are associated with worse outcomes.37,39 The outcome differences related to ophthalmic comorbidities may appear small (0.75-4.5 letters), but many patients may have multiple risk factors; thus, the additive risks should be considered preoperatively.

Interestingly, the current analysis found similar outcomes between DSBCS-14 and DSBCS-90. In fact, the DSBCS-14 group performed slightly better than the DSBCS-90 group, although the difference was fairly small (0.4-0.9 letters). This finding may be attributable to successful adjustment for any refractive surprise in the DSBCS-14 group between procedures (mean [SD], 11.44 [3.46] days), suggesting that a longer waiting period may be unnecessary. Refractive error has been reported to stabilize in healthy eyes approximately 1 week postoperatively47,48; given that most of the DSBCS-14 group had more than 7 days between operations, the adjustment might have impacted the second eye outcome.47,48 Preference for DSBCS may also depend on insurance because Medicare provides only 50% reimbursement for the second eye for ISBCS.49 Although this study did not include a cost analysis, others49,50 have found that ISBCS is more efficient and cost-effective in many cases, and some of those efficiencies, such as fewer follow-up visits or reduced presurgical care, may extend to DSBCS-14.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. This study only reports associations and cannot evaluate cause-and-effect relationships. The electronic health records and International Classification of Diseases and Current Procedural Terminology codes may have included misclassified or missing data. The current IRIS Registry does not include details such as axial length or topography. It is hoped that future versions will include more comprehensive data, but the lack of standardized ontologies to encode this type of data in electronic health record systems remains a significant barrier. It is possible that the visual outcome differences found in this study are attributable to residual confounding effects of controlled covariates in the models and/or unmeasured confounders associated with visual outcomes, such as intraoperative techniques. Patients were not assigned randomly to surgical groups, and patient-related confounders, such as medical, ocular, or social comorbidities and/or surgeon preference, may have affected group selection, limiting the generalizability of our findings. The fact that DSBCS-14 had better outcomes than DSBCS-90 (which had the best opportunity for assessing first eye outcomes) may support this possibility. However, many of these unmeasured factors likely reflect what practitioners confront in clinics. The goal of this study was to evaluate whether appreciable outcome differences remain between surgical groups that were selected in the routine clinical setting. Although the unprecedented size of the IRIS Registry is a strength, allowing us to detect minimal outcome differences between groups, including the DSBCS-14 group, which has never been analyzed, these differences may not be clinically relevant despite significant P values because of the large study sample size. The findings of this study are similar to other studies,5,21,51,52 with the exception that patients with additional risk factors and comorbidities may have larger visual outcome differences.

Conclusions

On the basis of data from the clinical practice setting of nearly 2 million bilateral cataract surgery patients, this study found that ICBCS was associated with worse visual outcomes when compared with DSBCS-90 or DSBCS-14, although the difference may not be clinically relevant. Race other than White, Medicaid coverage, and comorbid eye disease were independently associated with worse outcomes regardless of correction. Although these factors should be considered when counseling patients preoperatively, further studies to evaluate other potential confounders are warranted because they may explain the small outcome differences found between the surgery groups.

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) Codes Used in the Study.

eTable 2. Baseline Visual Acuity by DSBCS-90, DSBCS-14, and ISBCS Group

eTable 3. Univariable Linear Regression Results for Postoperative Visual Acuity

eTable 4. Multivariable Linear Regression Results With the Eye With Worse Pre-surgical Visual Acuity Assigned as the First Eye for the ISBCS Surgery Group

eTable 5. Multivariable Linear Model Results for Postoperative Visual Acuity With Surgeon Surgery Volume Included

eTable 6. Percentage of Bilateral Surgery Patients From All Years of the IRIS® Registry in Each Surgery Group (DSBCS-90, DSBCS-14, ISBCS) by Surgeon Cataract Surgery Volume

eResults. Supplemental Results

Nonauthor Collaborators

References

- 1.Congdon N, O’Colmain B, Klaver CC, et al. ; Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group . Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):477-485. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Congdon N, Vingerling JR, Klein BE, et al. ; Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group . Prevalence of cataract and pseudophakia/aphakia among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):487-494. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Eye Institute. Cataract data and statistics. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/resources-for-health-educators/eye-health-data-and-statistics/cataract-data-and-statistics

- 4.Medeiros S. Cataract surgery infographic. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Published October 6, 2014. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/news/cataract-surgery-infographic

- 5.Herrinton LJ, Liu L, Alexeeff S, Carolan J, Shorstein NH. Immediate sequential vs. delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery: retrospective comparison of postoperative visual outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(8):1126-1135. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.03.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turnbull AMJ, Barrett GD. Using the first-eye prediction error in cataract surgery to refine the refractive outcome of the second eye. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019;45(9):1239-1245. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2019.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jivrajka RV, Shammas MC, Shammas HJ. Improving the second-eye refractive error in patients undergoing bilateral sequential cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(6):1097-1101. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grzybowski A, Wasinska-Borowiec W, Claoué C. Pros and cons of immediately sequential bilateral cataract surgery (ISBCS). Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2016;30(4):244-249. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessel L, Andresen J, Erngaard D, Flesner P, Tendal B, Hjortdal J. Immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:912481. doi: 10.1155/2015/912481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eyeworld Supplements. ASCRS CLINICAL SURVEY 2018. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://supplements.eyeworld.org/i/1054151-ascrs-clinical-survey-2018/1?

- 11.Li O, Kapetanakis V, Claoué C. Simultaneous bilateral endophthalmitis after immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery: what’s the risk of functional blindness? Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(4):749-751.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arshinoff SA, Bastianelli PA. Incidence of postoperative endophthalmitis after immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(12):2105-2114. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamoureux EL, Fenwick E, Pesudovs K, Tan D. The impact of cataract surgery on quality of life. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22(1):19-27. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283414284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Academy of Ophthalmology. IRIS Registry. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://www.aao.org/iris-registry

- 15.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiang MF, Sommer A, Rich WL, Lum F, Parke DW II. The 2016 American Academy of Ophthalmology IRIS® Registry (Intelligent Research in Sight) database: characteristics and methods. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(8):1143-1148. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee CS, Owen JP, Yanagihara RT, et al. Smoking is associated with higher intraocular pressure regardless of glaucoma: a retrospective study of 12.5 million patients using the Intelligent Research in Sight (IRIS®) Registry. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2020;3(4):253-261. doi: 10.1016/j.ogla.2020.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundström M, Albrecht S, Nilsson M, Aström B. Benefit to patients of bilateral same-day cataract extraction: randomized clinical study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32(5):826-830. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.01.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nassiri N, Nassiri N, Sadeghi Yarandi SH, Rahnavardi M. Immediate vs delayed sequential cataract surgery: a comparative study. Eye (Lond). 2009;23(1):89-95. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serrano-Aguilar P, Ramallo-Fariña Y, Cabrera-Hernández JM, et al. Immediately sequential versus delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery: safety and effectiveness. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(10):1734-1742. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarikkola AU, Uusitalo RJ, Hellstedt T, Ess SL, Leivo T, Kivelä T. Simultaneous bilateral versus sequential bilateral cataract surgery: Helsinki Simultaneous Bilateral Cataract Surgery Study report 1. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(6):992-1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zetterberg M, Montan P, Kugelberg M, Nilsson I, Lundström M, Behndig A. Cataract surgery volumes and complications per surgeon and clinical unit: data from the Swedish National Cataract Register 2007 to 2016. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(3):305-314. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell CM, Hatch WV, Cernat G, Urbach DR. Surgeon volumes and selected patient outcomes in cataract surgery: a population-based analysis. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(3):405-410. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Modjtahedi BS, Hull MM, Adams JL, Munz SJ, Luong TQ, Fong DS. Preoperative vision and surgeon volume as predictors of visual outcomes after cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(3):355-361. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aristodemou P, Knox Cartwright NE, Sparrow JM, Johnston RL. First eye prediction error improves second eye refractive outcome results in 2129 patients after bilateral sequential cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(9):1701-1709. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guber I, Rémont L, Bergin C. Predictability of refraction following immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery (ISBCS) performed under general anaesthesia. Eye Vis (Lond). 2015;2:13. doi: 10.1186/s40662-015-0023-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arshinoff SA. IOL power prediction. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(12):2646. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jabbour J, Irwig L, Macaskill P, Hennessy MP. Intraocular lens power in bilateral cataract surgery: whether adjusting for error of predicted refraction in the first eye improves prediction in the second eye. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32(12):2091-2097. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed IIK, Hill WE, Arshinoff SA. Bilateral same-day cataract surgery: an idea whose time has come #COVID-19. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(1):13–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahr MA, Hodge DO, Erie JC. Racial/ethnic differences in rates of complex cataract surgery among United States Medicare beneficiaries. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(2):140-143. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2017.10.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X, Cotch MF, Ryskulova A, et al. Vision health disparities in the United States by race/ethnicity, education, and economic status: findings from two nationally representative surveys. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(6, suppl):S53-S62.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.08.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mundy KM, Nichols E, Lindsey J. Socioeconomic disparities in cataract prevalence, characteristics, and management. Semin Ophthalmol. 2016;31(4):358-363. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2016.1154178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shahbazi S, Studnicki J, Warner-Hillard CW. A cross-sectional retrospective analysis of the racial and geographic variations in cataract surgery. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wesolosky JD, Rudnisky CJ. Relationship between cataract severity and socioeconomic status. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48(6):471-477. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zambelli-Weiner A, Crews JE, Friedman DS. Disparities in adult vision health in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(6 suppl):S23-S30.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang W, Yan W, Müller A, He M. A global view on output and outcomes of cataract surgery with national indices of socioeconomic development. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(9):3669-3676. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-21489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu L, Herrinton LJ, Alexeeff S, et al. Visual outcomes after cataract surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019;45(4):404-413. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stock MV, Vollman DE, Baze EF, Chomsky AS, Daly MK, Lawrence MG. Functional visual improvement after cataract surgery in eyes with age-related macular degeneration: results of the Ophthalmic Surgical Outcomes Data Project. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(4):2536-2540. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-16069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han MM, Song W, Conti T, et al. Visual acuity outcomes after cataract extraction with intraocular lens implantation in eyes with diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4(4):351-360. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2019.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lundström M, Brege KG, Florén I, Lundh B, Stenevi U, Thorburn W. Cataract surgery and quality of life in patients with age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(12):1330-1335. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.12.1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wen G, Tarczy-Hornoch K, McKean-Cowdin R, et al. ; Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group . Prevalence of myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism in non-Hispanic white and Asian children: Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(10):2109-2116. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.06.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varma R, Torres M, McKean-Cowdin R, Rong F, Hsu C, Jiang X; Chinese American Eye Study Group . Prevalence and risk factors for refractive error in adult Chinese Americans: the Chinese American Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;175:201-212. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeon S, Kim HS. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of cataract surgery in highly myopic Koreans. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2011;25(2):84-89. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2011.25.2.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee YH, Chen AX, Varadaraj V, et al. Comparison of access to eye care appointments between patients with Medicaid and those with private health care insurance. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(6):622-629. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.0813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sommer A, Tielsch JM, Katz J, et al. Racial differences in the cause-specific prevalence of blindness in east Baltimore. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(20):1412-1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111143252004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manoharan N, Patnaik JL, Bonnell LN, et al. Refractive outcomes of phacoemulsification cataract surgery in glaucoma patients. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(3):348-354. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2017.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sugar A, Sadri E, Dawson DG, Musch DC. Refractive stabilization after temporal phacoemulsification with foldable acrylic intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27(11):1741-1745. doi: 10.1016/S0886-3350(01)00894-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caglar C, Batur M, Eser E, Demir H, Yaşar T. The stabilization time of ocular measurements after cataract surgery. Semin Ophthalmol. 2017;32(4):412-417. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2015.1115089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neel ST. A cost-minimization analysis comparing immediate sequential cataract surgery and delayed sequential cataract surgery from the payer, patient, and societal perspectives in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(11):1282-1288. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.2074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Brien JJ, Gonder J, Botz C, Chow KY, Arshinoff SA. Immediately sequential bilateral cataract surgery versus delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery: potential hospital cost savings. Can J Ophthalmol. 2010;45(6):596-601. doi: 10.3129/i10-094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chung JK, Park SH, Lee WJ, Lee SJ. Bilateral cataract surgery: a controlled clinical trial. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2009;53(2):107-113. doi: 10.1007/s10384-008-0627-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rush SW, Gerald AE, Smith JC, Rush JA, Rush RB. Prospective analysis of outcomes and economic factors of same-day bilateral cataract surgery in the United States. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41(4):732-739. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) Codes Used in the Study.

eTable 2. Baseline Visual Acuity by DSBCS-90, DSBCS-14, and ISBCS Group

eTable 3. Univariable Linear Regression Results for Postoperative Visual Acuity

eTable 4. Multivariable Linear Regression Results With the Eye With Worse Pre-surgical Visual Acuity Assigned as the First Eye for the ISBCS Surgery Group

eTable 5. Multivariable Linear Model Results for Postoperative Visual Acuity With Surgeon Surgery Volume Included

eTable 6. Percentage of Bilateral Surgery Patients From All Years of the IRIS® Registry in Each Surgery Group (DSBCS-90, DSBCS-14, ISBCS) by Surgeon Cataract Surgery Volume

eResults. Supplemental Results

Nonauthor Collaborators