Background: Studies examining pregnant patients with COVID-19 have shown an increased risk for death in pregnant versus nonpregnant patients of reproductive age (1). However, these data are based on registries that are limited by a significant proportion of missing data, including pregnancy status, and likely have biased case ascertainment.

Objective: To evaluate the risk for in-hospital death among pregnant and nonpregnant patients of reproductive age hospitalized with COVID-19, because studies with more thorough ascertainment of COVID-19 in pregnancy are needed to provide the foundation for clinical management and health care policy.

Methods and Findings: We did a retrospective cohort study of patients in the Premier Healthcare Database, an all-payer data repository that captures 20% of U.S. hospitalizations. We included all female inpatients aged 15 to 45 years hospitalized from April to November 2020 with COVID-19. A patient was defined as pregnant if the encounter included any pregnancy-related diagnosis. This study did not include personally identifiable information and was exempted from review by the institutional review board of the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

To exclude asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 diagnoses due to positive results on screening tests, we used only patients with a viral pneumonia diagnosis (Supplement Table). We then did sensitivity analyses using subgroups of patients with an intensive care unit admission or mechanical ventilation.

Analyses were done using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). The Supplement provides detailed methods.

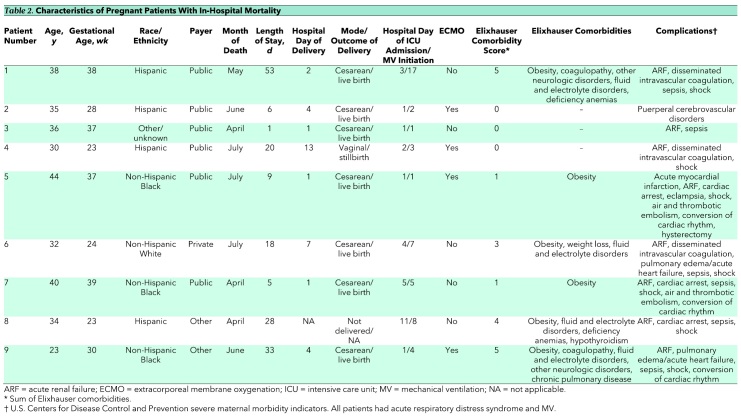

The cohort consisted of 1062 pregnant and 9815 nonpregnant patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and viral pneumonia. Pregnant patients were younger and more likely to have public insurance than nonpregnant patients (Table 1). Pregnant patients were also less likely to have most comorbid conditions, including hypertension, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes, and obesity.

Table 1. Characteristics and Outcomes Among Patients With COVID-19 and Viral Pneumonia Diagnoses*.

In-hospital death occurred in 0.8% (n = 9) of pregnant patients and 3.5% (n = 340) of nonpregnant patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and viral pneumonia (Table 1). Median time from admission to death was 18 days (interquartile range, 6 to 28 days) for pregnant patients and 12 days (interquartile range, 5 to 23 days) for nonpregnant patients. Among the subgroup of patients admitted to an intensive care unit, in-hospital mortality was 3.5% (9 of 255) in pregnant patients and 14.9% (283 of 1898) in nonpregnant patients. Among those who received mechanical ventilation, in-hospital death occurred in 8.6% (9 of 105) of pregnant patients and 31.4% (294 of 937) of nonpregnant patients.

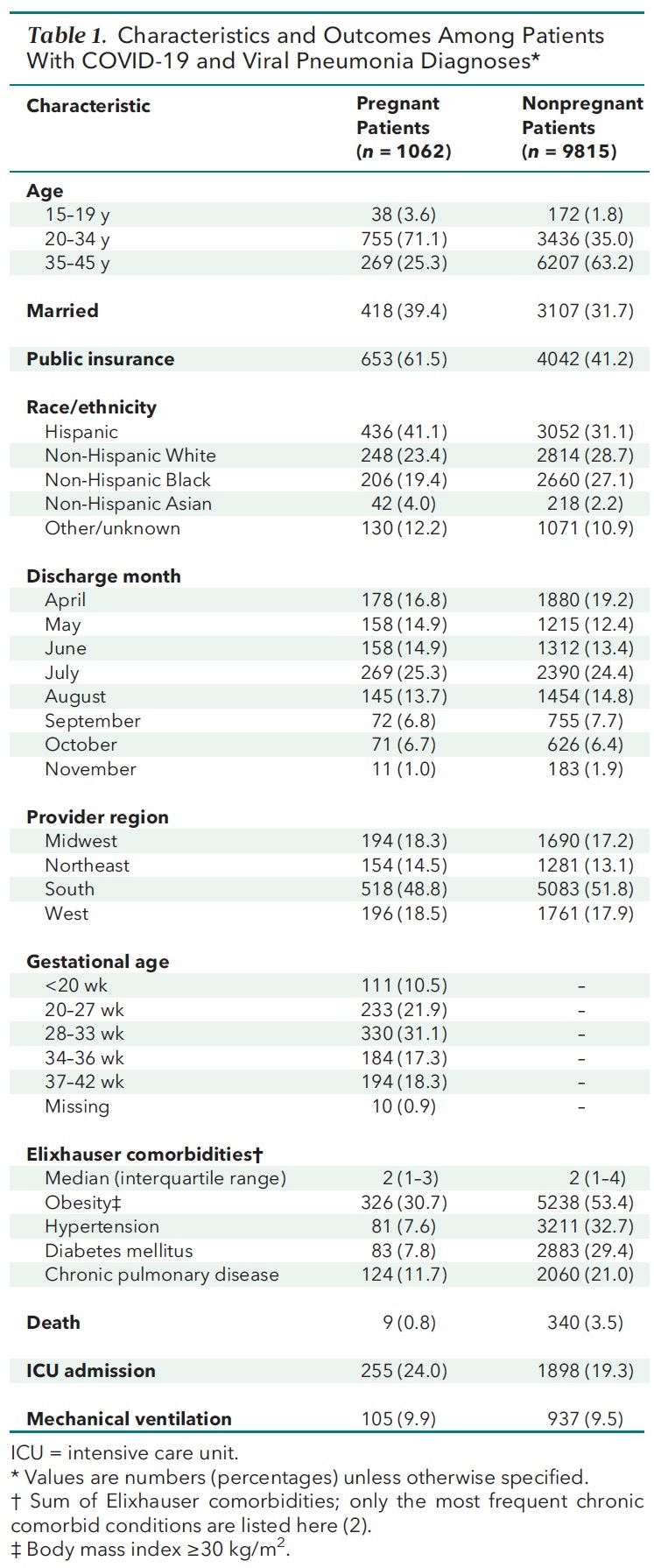

Pregnant patients who died are described in Table 2. Their ages ranged from 23 to 44 years. Eight were non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic. All died between April and July. Six were obese, and 7 had at least 1 comorbid condition. Gestational ages ranged from 23 to 39 weeks, and 7 of 9 deliveries were live births.

Table 2. Characteristics of Pregnant Patients With In-Hospital Mortality.

Discussion: Overall and within multiple subgroups, we found a substantially lower rate of in-hospital mortality in pregnant patients than nonpregnant patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and viral pneumonia. The rates found in this study are consistent with results of multiple other studies (3, 4). A cohort study including all symptomatic patients with COVID-19 aged 20 to 39 years hospitalized throughout the United Kingdom reported mortality of 0.8% in pregnant and 3.1% in nonpregnant persons (3).

Our study suggests lower mortality among pregnant patients than was initially reported. Using data collected from a voluntary reporting registry, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention observed a mortality rate of 0.15% among pregnant and 0.12% among nonpregnant patients, including both hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients (1). That study was limited in that pregnancy status was available for only 36% of patients, creating potential for case ascertainment bias (1).

A strength of our study is the use of a large database including patient discharge data from 853 hospitals. It is hospital-based, providing a clearly defined population without the biases of registry-based studies. However, some amount of collider bias is expected because both severity of disease and pregnancy affect the likelihood of hospitalization.

Other limitations include the small number of deaths, with resultant lack of adjustment for confounding. Results cannot be extrapolated to patients who are not hospitalized. Laboratory test results were unavailable, but prior research showed a strong correlation between COVID-19 diagnosis and laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (5).

In this large, geographically diverse cohort of reproductive-aged patients hospitalized with COVID-19, we found that in-hospital mortality was low in pregnant patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 11 May 2021.

References

- 1. Zambrano LD , Ellington S , Strid P , et al; CDC COVID-19 Response Pregnancy and Infant Linked Outcomes Team. Update: characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status — United States, January 22–October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1641-1647. [PMID: ] doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elixhauser A , Steiner C , Harris DR , et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8-27. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Knight M, Ramakrishnan R, Bunch K, et al. Females in hospital with SARS-CoV-2 infection, the association with pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes: a UKOSS/ISARIC/CO-CIN investigation. Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies; 2021.

- 4. Metz TD , Clifton RG , Hughes BL , et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network. Disease severity and perinatal outcomes of pregnant patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:571-580. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kadri SS , Gundrum J , Warner S , et al. Uptake and accuracy of the diagnosis code for COVID-19 among US hospitalizations. JAMA. 2020;324:2553-2554. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.20323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.