Foreword

Foreword – antimicrobial prescribing guidelines for poultry

Antimicrobials are essential to modern medicine for treating a range of infections in humans and animals. Importantly, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a growing global threat that presents a serious risk to human and animal health. Inappropriate and/or unrestrained use of antimicrobials in humans and animals exerts a strong selection pressure on microbial populations to evolve resistant traits. As a result, antimicrobials have become less effective over time leading to treatment complications and failures, and increased healthcare costs for people and animals. Resistant organisms spread between people, animals and the environment. Globalisation and international travel facilitates this spread between countries.

Here in Australia, the veterinary profession and food‐producing animal industries have a long history of addressing AMR. Their previous and ongoing work – a result of partnerships across the animal sector – has resulted in demonstrated low levels of AMR in our food‐producing animals. Over the past 5 years, the veterinary profession has consolidated its partnership with industry and government by helping to successfully implement Australia's First National Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy 2015–19. With the recent release of Australia's National Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy – 2020 and Beyond (2020 AMR Strategy), the veterinary profession will continue to play a critical role in how we minimise AMR.

One of the seven key objectives of the 2020 AMR Strategy relates to appropriate antimicrobial usage and antimicrobial stewardship practices. Resistance to antimicrobials occurs naturally in microorganisms, but it is significantly amplified by antimicrobial overuse, growth promotion use, and poor husbandry and management.

The antimicrobial prescribing guidelines for poultry directly addresses the fourth objective of the 2020 AMR Strategy, and in particular, Priority Area for Action 4.1, that seeks to ‘ensure that coordinated, evidence‐based antimicrobial prescribing guidelines and best‐practice supports are developed and made easily available, and encourage their use by prescribers’.

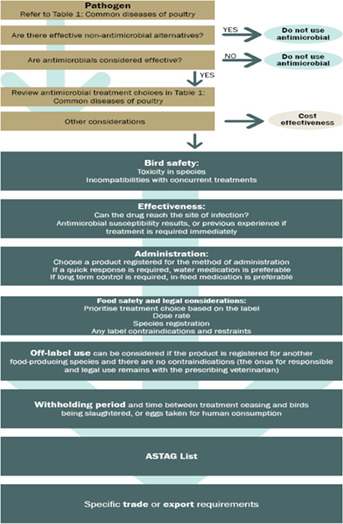

These guidelines for Australian poultry veterinarians are sure to be a ready resource. They have been developed specifically for the Australian poultry industry and contain best‐practice prescribing information to help clinical veterinarians in their day‐to‐day use of antimicrobials. The guidelines encourage veterinarians to first pause and consider the need to use antimicrobials in that circumstance: Are there effective non‐antimicrobial alternatives? Prevention and control of infections through strict on‐farm biosecurity is a recognised approach to minimising disease entry and the need to use antimicrobials. Vaccination may also be available to control several important poultry diseases. If antimicrobial use is indicated, have you considered the five rights: right drug, right time, right dose, right duration and right route? Using a lower rating or narrow‐spectrum antimicrobial is the preferred approach, and you can also refer to the Australian Antibacterial Importance Ratings to help with these decisions.

I commend the work of all involved in the development of these guidelines, and urge every poultry veterinarian to use this advice. In doing so, you will help safeguard the ongoing, long‐term efficacy of antimicrobials, deliver the best possible veterinary service to the Australian poultry industry, and play your role in the global response to AMR.

Dr Mark Schipp

Australian Chief Veterinary Officer

President of the OIE World Assembly

Expert panel members

Dr Peter Gray BVSc

Peter Gray graduated with a Bachelor of Veterinary Science from Sydney University in 1983. He spent 2 years in a pet and aviary bird‐focused private practice in western Sydney, and started with Inghams Enterprises in 1986 as a poultry veterinarian. During his ongoing work life at Inghams, Peter has had technical and veterinary roles that have involved him in all aspects of a poultry operation from importation, export, breeding, feed mills, hatching, growing, processing and further processing. His work has covered veterinary work in both chicken and turkey species, as well as welfare and food safety. He has always valued the learnings from many experienced colleagues both from within Inghams and the wider Australian Veterinary Poultry Association community. He has been a representative on industry and government committees, and is a qualified poultry welfare auditor with the Professional Animal Auditor Certification Organization (PAACO). Over the course of his working life, he has seen great change in the Australian industry where genetics, biosecurity, new vaccine strategies and improved management practices have seen an extensive reduction in antibiotic use in the poultry industry. He hopes these guidelines can play a part in continuing that positive trend while maintaining good welfare outcomes for the birds under our care.

Dr Rod Jenner BVSc

Rod Jenner is a consultant poultry veterinarian consulting to both the chicken meat and egg industries, and conducting projects on behalf of Agrifutures Australia and Australian Eggs Ltd. He has been in the poultry industry since graduation.

Rod has served on a number of industry representative committees over the years, including the RIRDC chicken meat advisory committee, and has also served as President of the Australian Veterinary Poultry Association (AVPA), member of Therapeutics Subcommittee and Welfare Subcommittee of the AVPA, Queensland executive of the AVA, and divisional committee of the WPSA. Of recent years, Rod has progressed into teaching veterinary students in the area of commercial poultry medicine at the University of Queensland and James Cook University.

Professor Jacqueline Norris BVSc MVS, PhD, FASM, MASID Grad Cert Higher Ed.

Jacqueline Norris is Professsor of Veterinary Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, and Associate Head of Research at the Sydney School of Veterinary Science, at the University of Sydney. She is a registered practicing veterinarian and is passionate about practical research projects and education programs for veterinary professionals, animal breeders and animal owners. Her main research areas include (1) development of diagnostics and treatments for companion animal viral diseases; (2) Q fever; (3) multidrug‐resistant (MDR) Staphylococcus species; (4) infection prevention and control in veterinary practices; (5) chronic renal disease in domestic and zoo Felids and (6) factors influencing antimicrobial prescribing behaviour of vets and health professionals.

Dr Stephen Page BSc(Vet)(Hons) BVSc(Hons) DipVetClinStud MVetClinStudMAppSci(EnvTox) MANZCVS(Pharmacology)

Stephen Page is a consultant veterinary clinical pharmacologist and toxicologist and founder and sole director of Advanced Veterinary Therapeutics – a consulting company that provides advice on appropriate use of veterinary medicines to veterinarians, veterinary organisations (Australian Veterinary Association, World Veterinary Association, World Organisation for Animal Health), state and national government departments and statutory bodies (APVMA, Department of Agriculture, Department of Health, US Environmental Protection Agency), and global organisations (OIE, FAO, Chatham House).

He is a member of the AVA Antimicrobial of Resistance Advisory Group (ARAG), a member of the ASTAG committee on antimicrobial prioritisation. In 2017, he became the President of the ANZCVS Chapter of Pharmacology, and is a member the World Veterinary Association Pharmaceutical Stewardship Committee.

He has more than 100 publications on which he is author or editor, including chapters on antimicrobial stewardship, clinical pharmacology, adverse drug reactions, use of antimicrobial agents in livestock, and antimicrobial drug discovery and models of infection.

Stephen Page has been a teacher and facilitator of courses at the University of Sydney on food safety, public health and antimicrobial resistance since 2003.

He is regularly invited to speak nationally and internationally at a broad range of conferences and symposiums, especially on the subjects of antimicrobial use, antimicrobial stewardship and risk assessment. He gave his first presentation on veterinary antimicrobial resistance and stewardship at the AVA Conference in Perth in 2000 and remains passionate about improving the use and effective life span of antimicrobial agents.

Professor Glenn Browning BVSc (Hons I) DipVetClinStud, PhD, FASM

Glenn Browning is Professor in Veterinary Microbiology, Director of the Asia‐Pacific Centre for Animal Health and Acting Head of the Melbourne Veterinary School at the University of Melbourne. He completed the Bachelor of Veterinary Science with First Class Honours at the University of Sydney in 1983, a postgraduate Diploma of Veterinary Clinical Studies in Large Animal Medicine and Surgery at the University of Sydney in 1984 and a PhD in Veterinary Virology at the University of Melbourne in 1988.

He was a Veterinary Research Officer at the Moredun Research Institute in Edinburgh from 1988 to 1991, investigating viral enteritis in horses, then joined the staff of the Faculty of Veterinary Science at the University of Melbourne, and has been a member of teaching and research staff there since 1991.

Professor Browning teaches in veterinary and agricultural microbiology. He is a Life Fellow of the Australian Veterinary Association, a Fellow of the Australian Society for Microbiology and Chair Elect of the International Organisation for Mycoplasmology.

He has co‐authored 235 peer‐reviewed research papers and book chapters, has edited two books on recent progress in understanding the mycoplasmas and has co‐supervised 50 research higher degree students. His research interests include the molecular pathogenesis and epidemiology of bacterial and viral pathogens of animals, the development of novel vaccines and diagnostic assays to assist in control of infectious diseases, and antimicrobial stewardship in veterinary medicine.

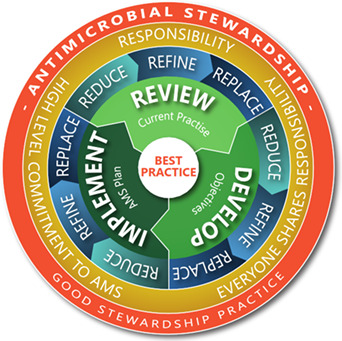

The 5R framework for good antimicrobial stewardship

Derived from: Page S, Prescott J and Weese S. Veterinary Record 2014;175:207‐208. Image courtesy of Trent Hewson, TKOAH.

Contents

| Core principles of appropriate use of antimicrobial agents | 4 |

| Introduction | 6 |

| Interactions contributing to pharmacokinetic variability | 9 |

| Conclusion | 11 |

| Disease investigation – general approach | 11 |

| Diseases of the digestive tract | 12 |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 34 |

| Diseases of the locomotory system | 37 |

| Systemic diseases | 39 |

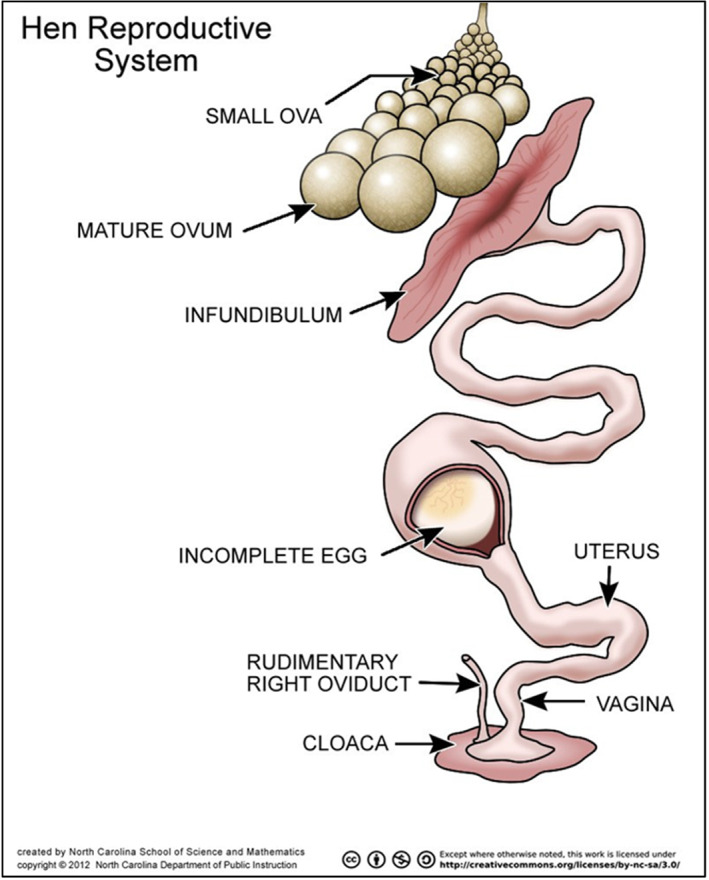

| Diseases of the reproductive system | 41 |

| Diseases of the nervous system | 44 |

| Immunosuppressive diseases | 45 |

| Diseases of the young chick | 46 |

| Treatment | 48 |

| Diseases of turkeys, ducks and other poultry | 48 |

| Considerations for choice of first priority antimicrobials | 49 |

| References | 49 |

Core principles of appropriate use of antimicrobial agents

While the published literature is replete with discussion of misuse and overuse of antimicrobial agents in medical and veterinary situations there has been no generally accepted guidance on what constitutes appropriate use. To redress this omission, the following principles of appropriate use have been identified and categorised after an analysis of current national and international guidelines for antimicrobial use published in the veterinary and medical literature. Independent corroboration of the validity of these principles has recently been provided by the publication (Monnier et al 2018) of a proposed global definition of responsible antibiotic use that was derived from a systematic literature review and input from a multidisciplinary international stakeholder consensus meeting. Interestingly, 22 elements of responsible use were also selected, with 21 of these 22 elements captured by the separate guideline review summarised below.

Pre‐treatment principles

-

Disease prevention

Apply appropriate biosecurity, husbandry, hygiene, health monitoring, vaccination, nutrition, housing, and environmental controls. Use Codes of Practice, Quality Assurance Programmes, Herd Health Surveillance Programmes and Education Programmes that promote responsible and prudent use of antimicrobial agents.

-

Professional intervention

Ensure uses (labelled and extra‐label) of antimicrobials meet all the requirements of a bona fide veterinarian‐client‐patient relationship.

-

Alternatives to antimicrobial agents

Efficacious, scientific evidence‐based alternatives to antimicrobial agents can be an important adjunct to good husbandry practices.

Diagnosis

-

4

Accurate diagnosis

Make clinical diagnosis of bacterial infection with appropriate point of care and laboratory tests, and epidemiological information.

Therapeutic objective and plan

-

5

Therapeutic objective and plan

Develop outcome objectives (for example clinical or microbiological cure) and implementation plan (including consideration of therapeutic choices, supportive therapy, host, environment, infectious agent and other factors).

Drug selection

-

6

Justification of antimicrobial use

Consider other options first; antimicrobials should not be used to compensate for or mask poor farm or veterinary practices.

Use informed professional judgement balancing the risks (especially the risk of AMR selection & dissemination) and benefits to humans, animals & the environment.

-

7

Guidelines for antimicrobial use

Consult disease‐ and species‐specific guidelines to inform antimicrobial selection and use.

-

8

Critically important antimicrobial agents

Use all antimicrobial agents, including those considered important in treating refractory infections in human or veterinary medicine, only after careful review and reasonable justification.

-

9

Culture and susceptibility testing

Utilise culture and susceptibility (or equivalent) testing when clinically relevant to aid selection of antimicrobials, especially if initial treatment has failed.

-

10

Spectrum of activity

Use narrow‐spectrum in preference to broad‐spectrum antimicrobials whenever appropriate.

-

11

Extra‐label (off‐label) antimicrobial therapy

Must be prescribed only in accordance with prevailing laws and regulations.

Confine use to situations where medications used according to label instructions have been ineffective or are unavailable and where there is scientific evidence, including residue data if appropriate, supporting the off‐label use pattern and the veterinarian's recommendation for a suitable withholding period and, if necessary, export slaughter interval (ESI).

Drug use

-

12

Dosage regimens

Where possible optimise regimens for therapeutic antimicrobial use following current pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) guidance.

-

13

Duration of treatment

Minimise therapeutic exposure to antimicrobials by treating only for as long as needed to meet the therapeutic objective.

-

14

Labelling and instructions

Ensure that written instructions on drug use are given to the end user by the veterinarian, with clear details of method of administration, dose rate, frequency and duration of treatment, precautions and withholding period.

-

15

Target animals

Wherever possible limit therapeutic antimicrobial treatment to ill or at‐risk animals, treating the fewest animals possible.

-

16

Record keeping

Keep accurate records of diagnosis (indication), treatment and outcome to allow therapeutic regimens to be evaluated by the prescriber and permit benchmarking as a guide to continuous improvement.

-

17

Compliance

Encourage and ensure that instructions for drug use are implemented appropriately

-

18

Monitor response to treatment

Report to appropriate authorities any reasonable suspicion of an adverse reaction to the medicine in either treated animals or farm staff having contact with the medicine, including any unexpected failure to respond to the medication.

Thoroughly investigate every treated case that fails to respond as expected.

Post‐treatment activities

-

19

Environmental contamination

Minimise environmental contamination with antimicrobials whenever possible.

-

20

Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance

Undertake susceptibility surveillance periodically and provide the results to the prescriber, supervising veterinarians and other relevant parties.

-

21

Continuous evaluation

Evaluate veterinarians' prescribing practices continually, based on such information as the main indications and types of antimicrobials used in different animal species and their relation to available data on antimicrobial resistance and current use guidelines.

-

22

Continuous improvement

Retain an objective and evidence guided assessment of current practice and implement changes when appropriate to refine and improve infection control and disease management.

Each of the core principles is important but CORE PRINCIPLE 11 Extra‐label (off‐label) Antimicrobial Therapy can benefit from additional attention as veterinarians, with professional responsibility for prescribing and playing a key role in residue minimisation, must consider the tissue residue and withholding period (WHP) and, if necessary, export slaughter interval (ESI) implications of off‐label use before selecting this approach to treatment of animals under their care (Reeves 2010; APVMA 2018).

The subject of tissue residue kinetics and calculation of WHPs is very complex requiring a detailed understanding of both pharmacokinetics (PK) and statistics, as both these fields underpin the recommendation of label WHPs. Some key points to consider when estimating an off‐label use WHP include the following:

The new estimate of the WHP will be influenced by (1) the off‐label dose regimen (route, rate, frequency, duration); (2) the elimination rate of residues from edible tissues and (3) the maximum residue limit (MRL).

Approved MRLs are published in the MRL Standard which is linked to the following A PVMA website page: https://apvma.gov.au/node/10806

If there is an MRL for the treated species, then the WHP recommended following the proposed off label use must ensure that residues have depleted below the MRL at the time of slaughter.

If there is no MRL for the treated species, then the WHP recommendation must ensure that no detectable residues are present at the time of slaughter.

Tissue residue kinetics may be quite different to the PK observed in plasma – especially the elimination half‐life and rate of residue depletion. The most comprehensive source of data on residue PK is that of Craigmill et al 2006.

WHP studies undertaken to establish label WHP recommendations are generally undertaken in healthy animals. Animals with infections are likely to have a longer elimination half‐life.

There are many factors that influence variability of the PK of a drug preparation, including the formulation, the route of administration, the target species, age, physiology, pathology and diet.

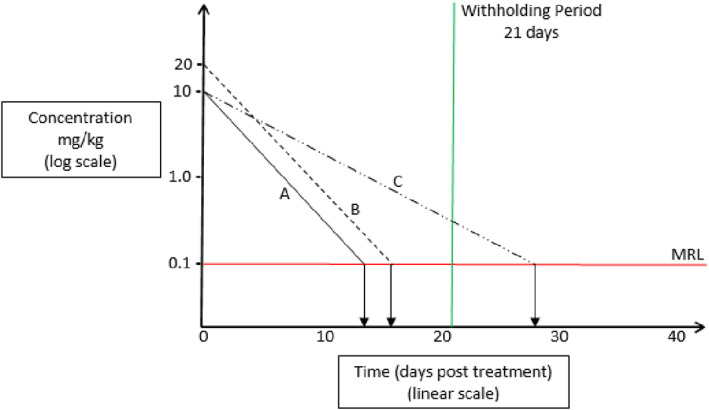

The following figure provides a summary of typical effects on elimination rates associated with drug use at higher than labelled rates and in animals with infections (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

An example of the relationship between the maximum residue limit (MRL) and tissue depletion following administration of a veterinary medicine. In a healthy animal (A), tissue depletion to the MRL often occurs at a time point shorter than the WHP that has been established for the 99/95th percentile of the population. In such an individual animal, if the dose is doubled, tissue depletion (B) should only require one more half‐life and would most likely still be within the established WHP. However, if the half‐life doubles due to disease or other factors, depletion (C) would now require double the normal WHP and may still result in residues exceeding the MRL (adapted from Riviere and Mason, 2011).

References

APVMA. Residues and trade risk assessment manual. Version 1.0 DRAFT. Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority, Kingston, ACT, 2018.

Craigmill AL, Riviere JE, Webb AI. Tabulation of FARAD comparative and veterinary pharmacokinetic data. Ames, Iowa, Wiley‐Blackwell, 2006.

Monnier AA, Eisenstein BI, Hulscher ME, Gyssens IC, Drive‐AB. WP1 Group. Towards a global definition of responsible antibiotic use: results of an international multidisciplinary consensus procedure. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2018;73:3‐16.

Reeves PT. Drug Residues. In: Cunningham F, Elliott J, Lees P, editors. Comparative and Veterinary Pharmacology. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010;265‐290.

Riviere JE, Mason SE. Tissue residues and withdrawal times. In: Riviere JE, editor. Comparative Pharmacokinetics Principles, Techniques, and Applications. second edn. Wiley‐Blackwell, Oxford, UK, 2011;413‐424.

Introduction

Management of disease outbreaks on a commercial poultry farm

Commercial poultry veterinary medicine is a unique stream of veterinary science that focuses strongly on preventive medicine. Infectious disease outbreaks are most commonly the result of lapses in biosecurity, which are not always totally preventable and should never be unexpected. Biosecurity in this context is more than quarantine. It has external, internal and resilience components, which include vaccination, preventive medication, optimal nutrition, appropriate genetics, good husbandry and exemplary management.

The methods used for diagnostic investigation are quite diverse, even though they are being applied to a single animal species, and often to the relatively uniform context of a commercial farm. Animal behaviour, or ethology, is the most frequently used diagnostic tool, and probably the least acknowledged skill used by a field veterinarian. Gross pathology, histopathology, epidemiology, microbiology, and serology are all important diagnostic tools, while the disciplines of immunology, pharmacology, therapeutics and veterinary medicine in public health are employed by commercial poultry veterinarians in the conduct of their role.

Disease treatment considerations

Food industry

The number one consideration is always that the veterinarian is operating within a food production system. Every decision about treatment must incorporate considerations about the wholesomeness of the animal or product as a human food source.

Food safety considerations are paramountTreatment options are severely limited.

Broiler chickens have a very short lifespan relative to antimicrobial treatment regimens. The prescribing veterinarian must be cognisant of the likely slaughter date of the flock before recommending treatments. The use and consequences of antimicrobial therapies must be clearly communicated with both the farmer and the owner/processor of the chickens to ensure that treatment will not contravene the advised WHP.

Egg laying flocks are in constant production, so advice on WHPs precludes the sale or supply of eggs into the food sector for the duration of the WHP for any medication that has a WHP longer than 0 days (NIL).

Backyard poultry flocks are commonly kept for enjoyment, egg production and occasionally for their meat. In most instances, movement of animals, eggs and meat is confined to the primary household. However, it is not uncommon for surplus eggs and chickens to be sold or given away to neighbours and work colleagues. Additionally, certain fancy varieties of backyard poultry may be extensively traded and sold between individuals. Therefore, the prescribing veterinarian must be aware of the medications that can be used safely in poultry and their associated WHPs. Inappropriate advice may have far‐reaching implications.

Treating a flock, not an individual

Treatments are generally applied to an entire flock, rather than to an individual bird. It is cost‐prohibitive to consider hospital pens in large‐scale operations, but this can be feasible in smaller niche farms, or with high value stock (e.g. rare breeds, genetically superior stock, or during situations of severe shortage). However, even high value commercial stocks are generally replaceable, so it is unusual to treat an individual commercial bird.

In contrast, in small backyard poultry flocks, it is common for owners to have a strong bond with their birds. In such instances, the birds may have become part of the family and the owners may be willing to go to extensive lengths to ensure their birds receive individual veterinary medical attention.

When treating a flock with an antimicrobial agent, consideration needs to be given to the long‐term commercial return, as well as the short‐term response.

Valid grounds for antimicrobial medication include animal welfare, managing the risks of disease in susceptible flocks, the zoonotic potential of the disease and true economic loss when there is a no more effective way to control the disease.

Medication is not justified when it will be ineffective, for example for viral or nutritional diseases.

Medication is often not the best approach to disease control, even though in theory, it may be effective. It may be best to process birds early or, in mild cases, let the disease run its course.

Medication can sometimes be counter‐productive, for example, when it may have an impact on live bacterial vaccines.

Medication is unwarranted if the intention is solely to provide non‐specific cover over stressful periods, to be seen to be doing something, to bring peace of mind, or to use up excess drug stocks.

Prudent use

It is important to remember that if antimicrobial therapy is being considered, mass medication in water or feed will not only target sick birds, but will be consumed by healthy birds. In addition, sick chickens tend to have reduced feed and water consumption, limiting their antimicrobial intake. Thus, mass antimicrobial therapy is not targeted therapy, but rather, is largely a preventive approach to limiting the spread of bacteria to healthy individuals.

Treatment options are severely limited in Australia by the restricted number of registered veterinary medicines available for administration in feed or water, and by food safety considerations, placing more emphasis on the importance of preventive measures.

Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs are not registered for use in poultry and are never used in poultry medicine, so therapeutic options are limited to antimicrobials. There are relatively few alternatives to preventive antimicrobial therapy, but options include (with variable evidence of efficacy) medium‐chain fatty acids, probiotics, prebiotics (for example, mannan oligosaccharide derivatives), acidifiers, essential oil extracts and many more.

The use of antimicrobials in commercial poultry production is under considerable pressure and can be influenced by major customers, with a growing expectation to demonstrate good antimicrobial stewardship, and an emphasis on strategies to reduce use. Veterinary intervention is closely scrutinised, and there is an increasing requirement to justify approaches to flock health when they involve the use of antimicrobial agents.

Backyard poultry: It can be difficult to design appropriate treatment regimens for backyard poultry due to the limited number of registered veterinary medicines available. Clients may place pressure on the prescribing veterinarian to provide medications that are not approved for use in poultry. This largely occurs when the birds are kept primarily as pets and their eggs are not consumed. It is important for the prescribing veterinarian to be aware that backyard poultry are classified as food‐producing species and to investigate which antimicrobial agents can be used safely and legally. If unregistered medicines or off‐label uses are prescribed, then the prescribing veterinarian must determine and recommend an appropriate WHP for eggs and meat.

Practical considerations

Diagnosis

It is essential that a diagnosis, even if only presumptive, is made before considering medication.

-

2

Drug susceptibility and resistance

All infectious organisms have an inherent pattern of susceptibility and resistance to specific drugs. Resistance to certain drugs may also be acquired. Acquired resistance may be determined by laboratory susceptibility tests or inferred by prior clinical experience and previous response to therapy on a particular farm, although it should always be remembered that prior clinical experience can be misleading, as clinical improvement of a flock may not have been a result of successful antimicrobial therapy. Sampling for susceptibility testing prior to antimicrobial use is essential.

-

3

Bactericidal vs bacteriostatic

Bactericidal antimicrobials kill bacteria, thereby reducing the number of organisms, whereas bacteriostatic antimicrobials inhibit the metabolism, growth or multiplication of bacteria, thereby preventing an increase in the number of organisms. In practice, this generally makes little difference, as a functional immune system is essential for resolution of all infectious diseases, regardless of the mode of action of the drug used to treat them.

-

4

Site of infection

Choosing a drug that will reach the site of infection at an effective concentration for enough time is an important consideration.

-

5

Dose rate

Having selected a drug that is likely to be effective, an appropriate dose rate must be determined. Dose rates should be selected and calculated using the following guidelines:

Water and feed consumption can vary considerably, and is affected by flock health, ambient temperature, species, physiological status and management practices. Therefore, where information is available, antimicrobial dose rates based on bodyweight, in conjunction with known current water or feed consumption, provide the most accurate dosages. The exception is in young rapidly growing birds, where dose rate expressed as a concentration in feed or water provides a more practical calculation method.

Treatment should always commence at maximum recommended dose rates for the greatest efficacy.

Dose rate may need to be adjusted to allow for spillage or wastage, which can be considerable, especially in ducks.

When calculating a dose to be delivered in water, it is necessary to know the:

Bodyweight of the flock (determined by weighing a representative sample of birds)

Amount of water expected to be consumed during the medication period

Required dose rate

Concentration of the active ingredient in the selected antimicrobial product

-

6

Onset of medication

Normally treatment should commence as soon as a presumptive diagnosis is available when disease is acute and a high mortality rate is expected, for example, in fowl cholera (infection with Pasteurella multocida).

For more chronic disease, it is appropriate to wait for the results of susceptibility testing.

-

7

Frequency of medication

In theory, for time‐dependent antimicrobial agents, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of a drug should be maintained or exceeded at the site of infection throughout the course of treatment to ensure that the infecting organism remains suppressed and is less likely to acquire resistance. It is critical to ensure that the amount of medicated water supplied each day is sufficient to eliminate the risk of birds running out of water during times when the manager is not on the farm (e.g. overnight).

-

8

Duration of medication

In acute disease outbreaks, medication should continue until mortalities stop and clinical signs are no longer apparent in the flock. Usually this takes at least 3 days, and mortalities may continue to rise for the first few days as severely affected birds succumb, especially if they are too sick to consume any medication. However, acute diseases are usually under control within 5–7 days, and if no response is apparent within 3–5 days, the diagnosis and treatment regimen should be reassessed.

Some diseases may require ongoing medication in feed or water to suppress clinical disease and potential spread to other flocks.

-

9

Routes of administration

Oral administration is most effective for infections involving the digestive tract. Drinking water medication is usually more effective than in‐feed medication, as it can be commenced and altered more quickly, and because sick birds may continue drinking even when they have ceased eating. There is also less risk of consumption by non‐target birds/species. It is important that, as the medicated water is consumed, the dose is not diluted with fresh water. Birds should have no access to other water sources.

The efficacy of many antimicrobials can be affected by the route of administration. Once powders are dissolved in solution, or liquids diluted, the drug can lose its activity. As a rule, medications should be prepared daily. Antimicrobials should not be mixed or administered concurrently, as one may interfere with the solubility, absorption or activity of another.

The pharmacology of antimicrobial agents in poultry

Within the critical context of antimicrobial stewardship, it is important to select drug and dosage regimens that reflect the five rights – right drug, right time, right dose, right duration and right route. 1 There are many physiological, pathological and pharmacological sources of variation in antimicrobial drug exposure within and between birds of the same and different species (e.g. chickens, ducks and turkeys), to which can be added sources of variation within and between routes of administration.

There have been several recent reviews of antimicrobial use in poultry 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 and key findings are presented in this summary.

The potential for distribution of antimicrobial agents into the eggs of laying birds is an important consideration when developing treatment plans for laying birds and this subject has been comprehensively evaluated. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 As seen in Appendix 2, there are very few drugs approved for use in birds and even fewer for birds currently producing eggs for human consumption. This is primarily a consequence of the presence, often for prolonged periods, of residues of the antimicrobial agent or its metabolites in meat and/or eggs.

The antimicrobial agents approved for use in birds in Australia represent well‐established and aged classes that were developed for use from the 1940s to the 1970s. With the exception of avilamycin, the antimicrobial agents listed in Appendix 2 with antibacterial indications (amoxicillin, apramycin, bacitracin, chlortetracycline, erythromycin, flavophospholipol, lincomycin, neomycin, oxytetracycline, spectinomycin, sulfadiazine, sulfadimidine, tiamulin, trimethoprim, tylosin, virginiamycin) were available for use in poultry in Australia in 1989. Because of the age of the antimicrobial agents available for use and their availability in most cases from a range of generic sources, there has been very little recent investigation of their pharmacology 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 or efficacy, or optimal dosage regimens 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 for these agents.

When these antimicrobial agents were first approved for use in Australia, it was only necessary to establish the dose regimen based on clinical response to treatment in infection challenge studies and field confirmation studies. The trend in recent decades to define dosage regimens is much more sophisticated and frequently involves an integration of the pharmacokinetic (PK) behaviour of the drug in the target bird species with the pharmacodynamic (PD) response of the target pathogen, often established by in vitro microbiological methods (e.g. the MIC of a representative panel of isolate of the target pathogen).

Very few PK/PD studies are available to re‐examine the dosage regimens of currently approved antimicrobial agents, although the PK/PD profile of tiamulin in an experimental intratracheal infection model of Mycoplasma gallisepticum in young chickens has been described. 71 Although valuable information was obtained in this study, tiamulin is not widely used in Australia, as Mycoplasma gallisepticum is very effectively controlled by vaccination. Application of the mutant selection window approach to the evaluation of the killing of Mycoplasma gallisepticum has been investigated for danofloxacin, doxycycline, tilmicosin, tylvalosin and valnemulin. 72 However, none of these antimicrobial agents are registered for use in Australia and the efficacy of vaccination in control of mycoplasmoses in chickens obviates any need for their use.

Water and feed administration

The most practical and common route of administration of antimicrobial agents in poultry in Australia is per os, with drugs being mixed in water or feed. There is only a single class of antimicrobial agent registered for injection in poultry (lincomycin–spectinomycin) and, although in ovo injection commonly used outside Australia, 73 , 74 , 75 no antimicrobial agents are registered for this route in Australia.

Effective use of antimicrobial agents in water requires an understanding of the drug and its formulation, especially its stability and solubility, as well as knowledge of factors influencing water intake and thereby exposure of birds to the treatment. Inconsistent antimicrobial administration has been observed after intravenous infusion of drugs into individual patients, 76 so it can be assumed that drug delivery in water or feed to populations of birds will have many challenges, both in the medication and consumption of water and feed, and the systemic availability of administered drugs. At best, administration by the oral route to a population of birds can be expected to be associated with significant imprecision. 77

Key considerations about feed and water medication have been described by a number of authors 11 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 and include a range of important factors affecting water consumption, including bird age (absolute water consumption increases with age, but consumption per kg live weight decreases), environmental temperature and heat stress, water temperature, electrolyte composition of the water, the feeding regimen and the lighting program (during dark periods birds do not usually drink and a peak of water consumption can occur just after lights are turned on).

Other factors affecting water and feed consumption and drug availability are presented as follows in the sections on interactions and sources of variability.

Interactions contributing to pharmacokinetic variability

Avian metabolism

The metabolism of foreign compounds or xenobiotics, including antimicrobial agents, in birds has received some attention, 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 but is not nearly as well understood as the metabolism of drugs in mammalian species.

One notable observation in birds is the ability of chickens to metabolise monensin and other ionophores, allowing them to be used with caution, but greater safety than in many mammalian species. 88 When the metabolism of monensin is impaired by coadministration of tiamulin, an inhibitor of Cytochrome P450 family 3 subfamily A (CYP3A) enzymes, monensin biotransformation is reduced, monensin accumulates, the margin of safety is eroded and toxicity can be observed. Not all ionophores are equally susceptible to the consequences of concurrent tiamulin exposure – for example, the safety of lasalocid 100 does not appear to be affected.

Other impacts of drugs on the CYPs of poultry have been described and include effects associated with sulfadimidine, 101 sanguinarine, 102 and the interaction of butyrate and erythromycin. 103

It is clear that there are some unique features of avian metabolism and that there are important differences in drug metabolism within species of birds and, importantly, between species. 89 For this reason, caution is required when using a new drug or a well‐established one in a new bird species.

Transport proteins

Transport proteins play an essential role in the absorption, distribution and excretion of drugs and toxins 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 and are located throughout the body in the cytoplasmic membranes of cells of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, kidney and brain. It is likely, just as observed in mammals, that there are important differences within and between species of birds in the rate and extent of drug transport across membranes and consequent PK.

Adsorption

Adsorption of drugs to the surface of chemical substances with particular properties can lead to reduced local and systemic availability. Examples include the interaction of bentonite and tylosin, 108 , 109 mycotoxin binders and tetracyclines, 110 tylosin and salinomycin 111 and, potentially, biochar immobilisation of lipophilic substances. 112

Tetracycline solubility and chelation

The bioavailability of chlortetracycline can be reduced by the presence of high concentrations of calcium and NaSO4 113 and increased in a low pH environment, as may occur following administration of citric acid to chickens 114 or turkeys. 115

Drug–drug interactions

A number of drug–drug interactions (DDIs) have been described in poultry between drugs not registered for use in birds in Australia, for example between doxycycline and diclazuril or halofuginone, 116 flunixin and doxycycline 117 and ionophores and florfenicol, 118 as well as between registered drugs, for example between monensin and sulphonamides. 119 The potential for DDIs should always be considered when more than one drug is used.

As described above, the best known DDI is between tiamulin and the ionophores, 100 and has been seen with monensin 120 and salinomycin. 121

Drug–herb interactions

A number of plants contain bioactive substances that can lead to interactions, such as that seen between silymarin and doxycycline in quail. 122

Hard water

Hard water can interfere with absorption, leading to decreased plasma concentrations of enrofloxacin 123 (not registered for use in poultry in Australia) and reduced availability of oxytetracycline. 55 , 124

Microbial degradation

Lactobacillus species in the crop of birds have been associated with the degradation of orally administered erythromycin. 125 , 126

Prandial status

Although not registered for use in poultry in Australia, the bioavailability of doxycycline is substantially reduced in the presence of feed, 127 highlighting prandial status as a potential source of variation. However, it is usually neither practical nor desirable to administer oral treatments to birds that have been fasted.

Water sanitisers

Water sanitisers can adversely affect the stability of antimicrobial agents, such as amoxicillin 128 and other antimicrobial agents. 129

Other sources of variability

A large number of pharmaceutical, physiological, pathological and pharmacological factors have been described as having an impact on the PK and clinical outcomes of antimicrobial use, particularly in mammals. 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 However, there are a growing number of examples of factors influencing PK and clinical outcome in poultry, with representative examples presented below. It should be recognised that most of the examples on sources of PK variation have been reported in studies of antimicrobial agents not registered for use in birds in Australia (all registered antimicrobial agents are set out in Appendix 2). However, the findings of these studies do highlight the diversity of sources of variation that need to be considered when designing dosage regimens or investigating poor responses to treatment.

Dose imprecision

Delivery of drugs in water or feed to populations of birds of variable weight and health makes delivering a predictable, accurate and intended dose impossible. 77 Measures can be introduced to reduce the degree of imprecision, but there will always be birds receiving less than or more than the target dose.

Age

The age of birds can have an impact on PK 134 and has been shown to influence the bioavailability of enrofloxacin, which was increased by 15.9% in 8‐week‐old broilers compared with that in 4‐week‐old birds. 104 In contract, plasma concentrations of sulfaquinoxaline and sulfadimidine were higher in younger broilers than in older birds. 135 Age and growth of broilers has also been shown to have a significant impact on the PK of florfenicol. 136

Bacterial isolate variation

When multiple isolates of Gallibacterium anatis were taken from various organs of layers, significant variation in antimicrobial resistance was observed. 137 This clearly can have an impact on clinical success if dose regimens are inadequate to control the full spectrum of resistances present.

Circadian variation

When monitored throughout the day, tylosin concentrations in plasma from broilers were subtherapeutic at night, an unfavourable finding for a time‐dependant antibacterial agent. 138 It is likely that there was no water and feed consumption during the night.

Sulfadimidine given orally to chicks was found to have dramatic differences in PK throughout the day, 139 sufficient to question the reliability of dosage regimens.

Fatty liver

Induced fatty liver in chickens led to significant changes in the PK of erythromycin, lincomycin and oxytetracycline. 140

Taste

Chickens have a small repertoire of bitter taste receptors (T2R) and the umami receptor (T1R1/T1R3) responds to amino acids such as alanine and serine. They lack a counterpart of the mammalian sweet sensing T1R2, so T1R2‐independent mechanisms for glucose sensing might be particularly important in chickens. The avian nutrient chemosensory system is present in the gastrointestinal tract and hypothalamus and is related to the enteroendocrine system, which mediates the gut–brain dialogue relevant to the control of feed intake. 141

It may not necessarily be related to taste, but water intake has been shown to increase in birds fed lasalocid. 142

Formulation

Modified formulations of doxycycline have been shown (not unexpectedly) to be associated with differing PK profiles in treated broilers. 143

Gender

Differences in the PK of antibacterial drugs (including the sulphonamides) have been shown when comparing hens and cockerels. 144 Tobramycin was eliminated more rapidly in ducks than in drakes, 145 similar to observations with apramycin. 144

Disease

Generally, antimicrobial agents are administered to birds that are affected by infection, from early subtle clinical stages to more obvious florid disease. While PK studies are frequently undertaken in normal birds, not surprisingly, the presence of disease can have a significant impact on PK and between and within bird variability in PK. The following examples illustrate the complexity and unpredictability of the effects of disease on the PK of various antibacterial agents. Most of the examples describe the use of antibacterial agents not registered for use in birds in Australia. However, the cases remain important as they demonstrate the importance of the impacts of disease on drug PK.

Amoxicillin administered to chickens with caecal coccidiosis was associated with a lower Cmax, a reduced AUC and lower bioavailability. 146

Endotoxaemia in turkeys had dramatic effects on cardiovascular function, but the PK of amoxicillin was not influenced, though PK was impacted by the rapid growth of the birds. 147

Infection of turkeys with Pasteurella multocida resulted in higher plasma levels of chlortetracycline (15 mg/kg) than in uninfected turkeys, and citric acid (150 mg/kg), a chelating agent of divalent cations such as calcium and magnesium, led to higher plasma levels in birds whether or not infected with Pasteurella multocida. 115 , 148

Danofloxacin (not registered) had a reduced Cmax in chickens infected with Pasteurella multocida, but the concentrations achieved adequately controlled infection. 149 However, with increasing pathogen MIC this may not always be the case.

In contrast, in ducks infected with Pasteurella multocida, danofloxacin (not registered) had a higher AUC. 150

Difloxacin (not registered) had increased clearance in broilers infected with Escherichia coli. 151

Doxycycline (not registered) had reduced plasma concentrations and a shorter elimination half‐life in chickens infected with Mycoplasma gallisepticum. 152

Enrofloxacin (not registered) had a reduced Cmax in broilers infected with Escherichia coli. 153

Enrofloxacin (not registered) was absorbed more slowly and had a shorter elimination half‐life in broilers infected with Escherichia coli. 154

Infection of broilers with Escherichia coli was associated with a decrease in the Vd and the elimination half‐life of florfenicol (not registered). 155

Florfenicol (not registered) had reduced Cmax and AUC0‐12 h values in lung tissue in Gaoyou ducks infected with Pasteurella multocida. 156

Florfenicol (not registered) had a reduced Cmax after administration by IM or IV in Muscovy ducks infected with Pasteurella multocida. 157

Infection of broilers with Salmonella gallinarum was associated with reduced clearance of kitasamycin (not registered). 158

Muscovy ducks with induced renal dysfunction had increased plasma concentrations of levofloxacin (not registered). 159

Infection of ducks with Pasteurella multocida was associated with increased plasma concentrations and slower elimination of orbifloxacin (not registered). 160

Chickens with infectious coryza had higher plasma concentrations, and reduced clearance (and possibly reduced residue elimination) of sulphachloropyridazine (not registered)–trimethoprim. 161

Conclusion

The effective treatment of birds with antimicrobial agents requires an understanding of the multitude of factors that influence selection of the appropriate drug, administration according to a route and dose regimen that increases the likelihood of adequate drug exposure of treated birds, and minimisation of those factors that are associated with PK variability.

The choice of antimicrobial agents is from a small formulary for treatment of birds with pathogens with evolving antimicrobial resistance status.

In many respects, it is amazing that drugs from the 1980s, and before, continue to provide clinical benefit. However, in the absence of monitoring of the PK and pathogen status of individual birds, the vigilance of farm personnel and the veterinarian in assessing the response to treatment is critical.

Disease investigation – general approach

Production records

Most commercial poultry farming operations have production records. These are useful indicators of the recent history of the flock. There are often also husbandry records that may provide clues about any recent husbandry or management factors that could influence the incidence and/or outcomes of disease. Vaccination programmes are also valuable sources of information. While some records may not be immediately available, a little time spent requesting and assessing further information is often well worth the effort. 162

An important consideration when investigating infectious diseases is to review the farm location and the placement of nearby farms. A quick view on Google Earth prior to your visit may assist in identifying potential risks, including nearby farms and dams on which wild waterfowl may reside. The other important records to review are the recent visitor entries, feed/gas deliveries, water sources and water sanitation.

Prior to arrival, ask the farmer to keep recently deceased or currently affected birds for you, to maximise your chance of a rapid diagnosis.

Ask if there have been recent disease outbreaks in the area, or previously on the farm.

If there have been severe clinical signs or mortalities, recommend that the flock/farm be quarantined until the visit.

Depending on the body system involved, there may be more specific details to be gathered. These will be covered, where appropriate, in each of the following chapters.

Flock examination

Farm and shed conditions should be the first part of flock examination. Observing the general farm conditions, biosecurity standards, rodent management and wild bird activity can greatly inform the general assessment of the husbandry and management standards employed by the farmer.

Inside the shed, indicators such as litter condition, air quality, temperature, humidity, lighting, and the availability of feed and water, are all important factors in disease investigation.

Flock behaviour is a good indicator of its general health status. Observations include bird distribution (huddling), general flock activity levels, noise levels, and eating and drinking behaviours.

In production systems where birds are not fed ad libitum, observing birds at feeding time is very useful.

Clinical examination – Signs of disease

The examination progresses to considering individual animals, looking for typical cases within the flock. Individual birds are very adept at disguising signs of illness and injury, so it is prudent to take the time to examine several birds to look for consistent clinical signs.

Post‐mortem examination

Once typical cases have been selected, 5–10 individuals can be selected for necropsy. Ideally, use cull chickens or recently deceased birds to reduce the risk of decomposition interfering with the gross and/or histological assessment, as well as microbiological diagnoses. On commercial farms, if the pathological signs of disease are not easily distinguished, the owner may allow some healthy birds to be euthanased as well to enable direct comparisons.

At this point, appropriate samples can be taken for laboratory investigation.

For advice on conducting a necropsy on a chicken, go to one of the following links:

https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/sites/gateway/files/A%20visual%20guide%20to%20a%20chicken%20necropsy.pdf

http://www.poultryhub.org/resources/poultry-videos/

Personal biosecurity, hygiene and the use of personal protective equipment should always be adopted when handling potentially infectious or zoonotic birds or samples from them. For advice on these matters, refer to the Australian Veterinary Association guidelines:

https://www.ava.com.au/library-resources/other-resources/veterinary-personal-biosecurity/

Treatment options

If a diagnosis can be made based on clinical signs and gross pathology, a treatment regimen can be commenced immediately. A presumptive bacterial infection would indicate the commencement of antimicrobial therapy only if there is enough time for treatment and the WHP can be complied with. The choice of drug is likely to be influenced by time constraints and food safety considerations as much as by susceptibility considerations.

Prevention advice

A good rule of thumb is that the recurrence of an identified problem is unsatisfactory! In commercial poultry medicine, preventive medicine is the ultimate goal. There is a wealth of knowledge and there are many tools available to assist a veterinarian in providing advice on disease prevention. Biosecurity, vaccinations, husbandry, nutrition and hygiene practices should all be discussed with a farmer in conjunction with treatment advice in the event of a disease outbreak.

Field veterinarian's kit [162]

| Disposable overalls | Bottles/tubes for blood collection (20) |

| Masks | Swabs and transport media (bacterial/viral) |

| Hairnets | Esky ice brick |

| Disposable gloves | Plain swabs |

| Biohazard bags | Sterile 100 mL jars |

| Rubbish bags | Tissue collection jars with 10% formalin solution |

| Scissors | Ammonia strips/metre |

| Knife | Thermometer/humidity metre, preferably with an anemometer (such as a Kestrel 3000) |

| Bucket/sanitiser | Camera/phone (washable case) |

| Water sanitation measurement device (strips measuring free chlorine/meter/test kit) and/or oxidation‐reduction potential meter | |

Diseases of the digestive tract

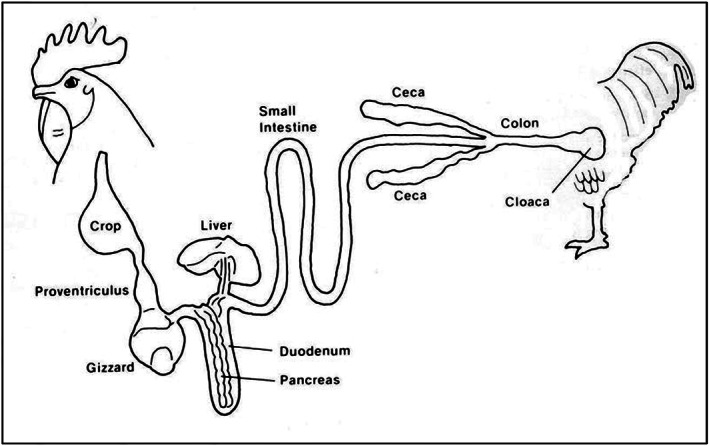

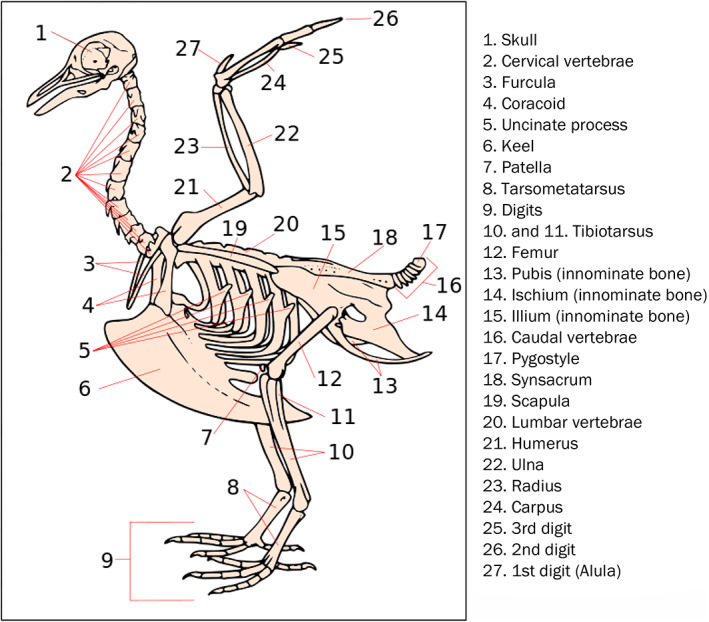

The digestive tract of birds has a significant number of differences from that of mammals, primarily to allow rapid food consumption and storage, and simple digestion (Figure 2).

| Oropharynx | Contains salivary glands, very few taste buds |

| Crop | Temporary food storage |

| Proventriculus | ‘True’ glandular stomach – acidification, enzyme addition, mixing of food |

| Ventriculus (gizzard) | ‘Mechanical stomach’, grinding and mixing of food |

| Duodenum | Pancreatic and hepatic enzyme and bile addition |

| Jejunum | Enzymatic digestion, nutrient absorption |

| Ileum | Further digestion, nutrient absorption |

| Caecum (plural: caeca) | Anaerobic fermentation of indigestible nutrients |

| Colon | Faecal accumulation and water absorption |

| Cloaca | Defecation and uric acid excretion |

Figure 2.

Schematic anatomy of the avian digestive system 163 (ErikBeyersdorf/CC BY‐SA; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by‐sa/3.0).

Each of the organs of the digestive tract of chickens has a specific role in the digestion and absorption of nutrients. The highly refined nature of commercial feedstuffs alters the functional homeostasis of the digestive tract of commercial chickens, leading to slight anatomical differences in organ size and shape from those of the backyard chicken.

The composition of the gastrointestinal microbiota (the community of commensal, symbiotic and pathogenic microorganisms) is a key functional component of general and gastrointestinal tract health and productivity in poultry.

The digestive tract has historically been the target of non‐specific antimicrobial treatments aimed at improving the productivity of flocks, through manipulation of the microbial population. However, increasing awareness of the need for improved antimicrobial stewardship has seen this practice disappear. Many non‐antimicrobial interventions (enzymes, organic acids, probiotics, prebiotics, essential oil extracts, yeast extracts) are now available to assist in the maintenance of a healthy gut microbiota, thus removing the need for antimicrobial therapies under normal growing conditions. 164 , 165 , 166 , 167 However, 168 imbalances in the microbiota can and do occur, leading to both clinical disease and subclinical, production‐limiting infections.

| General approach | |

|---|---|

| Specific considerations for investigations of digestive tract disease |

Gastrointestinal tract health is such an important component of bird health and productivity that even subtle non‐specific changes to gut health and physiology can have a significant bearing on flock health and performance. It is important for the clinician to have a very good understanding of normal gut morphology and physiology in order to detect mild pathological changes or altered intestinal contents. Wet droppings can be due to either digestive or urinary tract problems. It is important to differentiate between the two early in the case investigation. |

| Before farm entry | Look at mortality and production records. Review other farm records. Review current coccidiostat and worming programs. |

| On farm | Observe:

|

| Disease presentations/differential diagnosis 164 | |

|---|---|

| Diseases of the oropharynx | Epithelial lesions – necrotic, erosive, inflammatory, hyperkeratotic |

| Differential diagnosis |

Viral Fowlpox virus Fungal Candida albicans Toxic Mycotoxins Nutritional Vitamin A deficiency Protozoal Canker (trichomoniasis) |

| Diseases of the crop | Pendulous crop, sour crop, crop impaction |

| Differential diagnosis |

Fungal Candida albicans Physical Overeating, grass eating |

| Diseases of the proventriculus | Erosion, dilatation, inflammation |

| Differential diagnosis |

Viral Infectious proventriculitis Newcastle disease virus Avian influenza virus Unknown/nutritional Flaccid proventriculus (proventricular dilatation disease) Toxic Mycotoxins Biogenic amines |

| Diseases of the ventriculus (gizzard) | Erosion, flaccidity, atrophy |

| Differential diagnosis |

Viral Adenoviruses Toxic Mycotoxins Biogenic amines Unknown/nutritional Atrophy (linked to flaccid proventriculus) Low fibre diet Bacterial Clostridium perfringens |

| Diseases of the small and large intestines | Diarrhoea, depression, lethargy, runting/stunting, mortality |

| Differential diagnosis |

Bacterial Necrotic enteritis (Clostridium perfringens) Dysbacteriosis Spirochaetosis Protozoal Coccidiosis (Eimeria tenella/Eimeria brunetti/Eimeria necatrix/Eimeria maxima) Viral Adenoviruses, enteroviruses, rotaviruses, coronavirus, astrovirus, reoviruses, parvovirus Parasitic Intestinal nematodes, cestodes Nutritional Nutritional imbalances |

| Diseases of the caeca | Abnormal caecal droppings |

| Differential diagnosis |

Protozoal Coccidiosis Blackhead (Histomonas meleagridis) Trichomonads Bacterial Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (Salmonella Typhimurium) Parasitic Caecal worms (Heterakis gallinarum) Nutritional Excess or undigestible nutrients in the diet |

| Diseases of the liver | Liver pathology |

| Differential diagnosis |

Viral Marek's disease Lymphoid leukosis Inclusion body hepatitis Big liver‐spleen disease (hepatitis E virus) Bacterial Spotty liver disease (Campylobacter hepaticus) Salmonellosis (Salmonella spp.) Fowl cholera (Pasteurella multocida) Colibacillosis (Escherichia coli) Cholangiohepatitis (Clostridium perfringens) Staphylococcal infections Other septicaemic infections Protozoal Histomoniasis/Blackhead (Histomonas meleagridis) |

| Necropsy and sampling |

|---|

Necropsy 5–10 birds that have typical clinical signs or 5–10 birds that have recently died and note the findings. It is important to conduct a full examination of the digestive tract from mouth to cloaca.

|

Key issues.

The history will be important for determining the differential diagnosis. This will include vaccination and flock history, along with overall flock and necropsy signs.

It can be prudent to delay treatment until a diagnosis and antimicrobial susceptibility has been established, but this can depend on the level of mortality, the prognosis and the time until slaughter.

Treatment is not warranted for viral infections.

Coccidiosis is very common in backyard flocks and young chicks will almost invariably be challenged at some point. Older birds will develop immunity and will sporadically shed coccidial oocysts into the environment, thus perpetuating the infection cycle.

Intestinal worms are also very common in backyard flocks and a regular treatment program should be encouraged.

Coccidiosis

Background/nature of infection/organisms involved

Coccidiosis results from infection with members of the genus Eimeria. In the chicken, there are four common species, with a couple of less common species. Disease is generally seen in birds around 4–5 weeks of age, but can be seen in older flocks if exposure has been delayed, or if vaccinal immunity has waned. Secondary involvement of Clostridium perfringens can lead to necrotic enteritis.

With each diagnosis of coccidiosis, particularly if it is caused by Eimeria maxima and Eimeria necatrix, it is worthwhile performing a direct smear of the intestinal mucosa to look for an overgrowth of Clostridium perfringens, using a gram stain to identify the organism.

Treatment

The presence of a few coccidial lesions is a normal occurrence and does not indicate disease or warrant treatment.

If coccidiosis is strongly suspected, it is often appropriate to commence a course of anti‐coccidial medication based on pathology alone, as delaying treatment could result in high mortality rates because of the explosive course of the disease in intensively raised flocks.

Treatment choice is not affected by species of Eimeria, although the response to the treatment can be impacted. Eimeria necatrix infections tend to take longer to respond to treatment due to the severity of the lesions.

Anti‐coccidials used

Amprolium combined with ethopabate is the treatment of choice for short‐lived flocks such as broilers. Toltrazuril is suitable for longer‐lived or more valuable birds. Note that there are label restraints for both treatment options that must be followed.

Specific details on diseases, prevention and specific treatment choices can be found in Appendix 1. In food‐producing species, it is critical that contraindications and WHPs are reviewed as described in the label requirements and guidance in Appendix 2.

| Situation | First choice treatment | Second choice treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Short‐lived flock (e.g. broiler flock) | Amprolium/ethopabate. When in a concentration of amprolium 216 g/L and ethopabate 14 g/L, a dose rate of 500–1000 mL/900 L drinking water may be required for 5–7 days, depending on the severity of the disease. | Toltrazuril is administered at a dose rate of 3 L/1000 L for 2 consecutive days. Note that there is a 14‐day WHP for meat. |

| Long‐lived flock (e.g. layer flock, breeder flock, backyard flock, fancy breeds) up to 8 weeks before commencement of lay | Toltrazuril is administered at a dose rate of 3 L/1000 L for 2 consecutive days. This drug cannot be used in birds that will be laying eggs within 8 weeks of treatment. | Amprolium can be used at 250 mg/L of drinking water for 5–7 days, followed by a reduced dose rate of 150 mg/L of drinking water for 5–7 days to treat an outbreak. |

| Long‐lived flock (e.g. layer flock, breeder flock, backyard flock, fancy breeds) within 8 weeks of lay, or birds in lay | Amprolium can be used at 250 mg/L of drinking water for 5–7 days, followed by a reduced dose rate of 150 mg/L of drinking water for 5–7 days to treat an outbreak. | No alternative treatment. |

Necrotic enteritis

Background/nature of infection/organisms involved

Necrotic enteritis is caused by Clostridium perfringens. Necrotic enteritis is often found in association with coccidiosis and should be investigated in any suspect coccidiosis outbreak. Clostridium perfringens is a commensal in the chicken digestive tract under normal conditions, but it tends to overgrow and cause clinical disease when there is an excess of nutrients in the jejunum and ileum, which results in changes in the intestinal micro‐environment.

Treatment

If necrotic enteritis is suspected, then the treatment of choice until the diagnosis is confirmed would be amoxicillin at 20 mg/kg/day for three to five days, depending on the speed of recovery, whilst being aware of withholding periods as it will have good efficacy against Clostridium perfringens, has a short WHP and, since water soluble, can be applied immediately.

Another treatment option is Zinc bacitracin in feed at 200ppm active ingredient for 5‐7 days. However, as zinc bacitracin is not water soluble and requires in feed treatment this approach may not be practical in a sudden disease outbreak situation such as occurs with necrotic enteritis.

Where previous flock history suggests that necrotic enteritis is not able to be controlled with other measures as outlined in Appendix 1 (eg dietary) then preventative treatment with either zinc bacitracin in feed at a rate of 40 ppm (active ingredient) or avilamycin at a rate of 10‐15ppm (active ingredient) in feed may be required. The preventative treatment period will usually coincide with the times of coccidiosis challenge on the farm and is fed continuously through this risk period. Probiotics could also be considered as a potential alternative to antibiotics in these situations.

The choice of preventative treatment option will depend on applicable poultry species and production type, along with previous successful prevention regimes.

Zinc bacitracin can be used as per label directions in poultry with a nil withholding period for meat and egg production.

Avilamycin can only be used in broiler chickens.

Antibiotic treatment may be useful for necrotic enteritis prevention, but it is not a replacement for poor management, use of aggravating feed ingredients or inadequate coccidiosis control.

NOTE: Virginiamycin is also registered for use as a preventative treatment for necrotic enteritis. As it has a ‘HIGH’ ASTAG rating this antibiotic should only be used as a treatment of last resort and used strictly according to label directions.

Antimicrobials used

Specific details on diseases, prevention and specific treatment choices are shown in Appendix 1. In food‐producing species, it is critical that contraindications and WHPs are reviewed as described in the label requirements and guidance in Appendix 2.

| Situation | First choice treatment | Second choice treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Short‐lived flock not producing eggs (e.g. broiler flock) | Amoxicillin a in the drinking water is the first line treatment. Use at 20 mg/kg for 3 days. | Chlortetracycline can be used at a dose rate of 60 mg/kg bodyweight in drinking water for 3–5 days. |

| Long‐lived flock (e.g. layer flock, breeder flock, backyard flock, fancy breeds) up to 8 days before commencement of lay | Amoxicillin a in the drinking water is the first line treatment. Use at 20 mg/kg for 3 days. | Chlortetracycline can be used at a dose rate of 60 mg/kg bodyweight in drinking water for 3–5 days. |

| Long‐lived flock (e.g. layer flock, breeder flock, backyard flock, fancy breeds) in lay | If affected birds are producing eggs for human consumption, chlortetracycline can be used at 60 mg/kg bodyweight in drinking water for 3–5 days. | CCD amoxicillin trihydrate for poultry (APVMA # 36443) is currently the only amoxicillin formulation with a NIL WHP for eggs. However, it does have a 14‐day export egg WHP. Medicate at 20 mg/kg for 3–5 days in drinking water. |

CCD amoxicillin trihydrate for poultry (APVMA # 36443) is currently the only amoxicillin formulation with a NIL WHP for eggs. However, it does have a 14‐day export egg WHP.

Dysbacteriosis

Background/nature of infection/organisms involved

Dysbacteriosis is an imbalance of the normal bacterial flora, causing mild enteritis with wet droppings, leading to wet floors and dirty feathering, and potentially poor performance. It is mainly seen in broiler flocks. Lesions at necropsy include undigested feed, watery intestinal contents, flaccid intestines with a poor tone and excess caecal volume with gassy contents.

Treatment

Antimicrobial treatment is not recommended for dysbacteriosis. It is important to address the underlying cause.

Avian intestinal spirochaetosis

Background/nature of infection/organisms involved

Avian intestinal spirochaetosis (AIS) is caused by Brachyspira spp. (most commonly Brachyspira pilosicoli or Brachyspira intermedia). The typical presentation of AIS is a chronic diarrhoea causing stained vents and manure‐stained eggs. It is a disease of long‐lived floor‐based flocks. As the presentation is chronic, it is generally not reported in broiler flocks.

Specific details on diseases, prevention and specific treatment choices are shown in Appendix 1. In food‐producing species, it is critical that contraindications and WHPs are reviewed as described in the label requirements and guidance in Appendix 2.

| Situation | First choice treatment | Second choice treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Breeder and layer flocks | Chlortetracycline as an in‐feed treatment at 400 ppm for 7 days, followed, if necessary, by in‐feed treatment at 200 ppm for up to 28 days. | No alternative treatments. |

Salmonellosis

Background/nature of infection/organisms involved

Salmonella species do not usually cause clinical disease in poultry, unless there is an overwhelming infectious dose or concomitant immunosuppressive disease. Treatment of commercial broiler flocks is not recommended because of the food safety implications of clinical salmonellosis.

Treatment

Specific details on diseases, prevention and specific treatment choices are shown in Appendix 1. In food‐producing species, it is critical that contraindications and WHPs are reviewed as described in the label requirements and guidance in Appendix 2.

| Situation | First choice treatment (chicks under 2 weeks of age) | Second choice treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Flocks not producing eggs for consumption | Trimethoprim/sulphadiazine at a dose rate of 25 mg sulphadiazine/kg and 5 mg trimethoprim/kg per day for 3–5 days if the birds are less than 2 weeks old, or 12.5 mg sulphadiazine/kg and 2.5 mg trimethoprim/kg per day for 3–5 days if the birds are older than 2 weeks of age. | Amoxicillin a in the drinking water at 20 mg/kg for 3 days. |

CCD amoxycillin trihydrate for poultry (APVMA # 36443) is currently the only amoxicillin formulation with a NIL WHP for eggs. However, it does have a 14 days export egg WHP.

Spotty liver disease

Background/nature of infection/organism involved

Spotty liver disease is caused by Campylobacter hepaticus. It is a disease of longer‐lived floor‐living layer and breeder flocks and is rarely seen in caged birds or broilers. Clinical disease is almost invariably associated with a drop in egg production. The disease can occur throughout the year but tends to result in higher mortalities and greater drops in egg production in summer.

Antimicrobial treatment, although effective, should not be relied upon for long‐term control, as resistance to commonly used antimicrobials occurs rapidly.

Specific details on diseases, prevention and specific treatment choices are shown in Appendix 1. In food‐producing species, it is critical that contraindications and WHPs are reviewed as described in the label requirements and guidance in Appendix 2.

| Situation | First choice treatment | Second choice treatment |

|---|---|---|

| All situations | Chlortetracycline at 60 mg/kg bodyweight in drinking water for 5 days. | Lincomycin–spectinomycin at 100 g combined antibiotic activity/200 L in drinking water for 3–5 days. |

Histomoniasis

Background/nature of infection/organisms involved

Histomoniasis (or blackhead) is caused by a protozoan parasite, Histomonas meleagridis. Turkeys are highly susceptible, but disease is also seen in chickens. It is very rare in broilers. Lesions are commonly found in both the caeca (large caseous casts) and the liver (discrete circular lesions). It is often transmitted by the nematode Heterakis gallinae, so control of Heterakis gallinae will assist in control of histomoniasis in chickens. However, direct transmission occurs readily in turkeys.

Treatment

There is no currently registered treatment for histomoniasis. Consider control of the vector (Heterakis gallinae) and earthworms to reduce the incidence of disease.

Intestinal worms

Background/nature of infection/organisms involved

There is a wide range of nematodes and cestodes that can affect poultry, some of which are almost invisible to the naked eye. Intestinal worms should always be considered as a differential diagnosis, particularly in free‐range flocks. Faecal flotation can be used to detect eggs or tapeworm segments and assess the severity of an intestinal worm burden.

Treatment

Specific details on diseases, prevention and specific treatment choices are shown in Appendix 1. In food‐producing species, it is critical that contraindications and WHPs are reviewed as described in the label requirements and guidance in Appendix 2.

| Situation | First choice anthelmintic | Second choice anthelmintic |

|---|---|---|

| Ascaridia galli | Levamisole at 28 mg/kg live weight. As a guide, assuming a medicated water intake of 35 mL/bird over the treatment period, use 800 g levamisole per 900–1000 L drinking water, or 8 g per 10 L water for a small number of birds. The amount of solution prepared should be the volume that will be consumed over 12 h. Remove other sources of water during the treatment period. Note there is a 7‐day WHP for meat. | Piperazine (adult worms only). The recommended dose for poultry is 200 mg/kg (1 g per 5 kg bodyweight). Use 1 kg of Piperazine Wormer to treat 2500 birds with a bodyweight of 2 kg. The volume of medicated water provided should be able to be consumed by the birds over a 6 to 8 h period. Discard any remaining medicated water after 6–8 h. Add the amount required to a small quantity of water first. When it is completely dissolved, add it to the medication tank, mixing thoroughly. When treating a severe worm infestation, repeat the dose 17–21 days later. |

| All other species of immature and mature nematodes | Levamisole at 28 mg/kg live weight. As a guide, assuming a medicated water intake of 35 mL/bird over the treatment period, use 800 g levamisole per 900–1000 L drinking water, or 8 g per 10 L water for a small flock. The amount of solution prepared should be the volume that will be consumed over 12 h. Remove other sources of water during the treatment period. Note there is a 7‐day WHP for meat. | Flubenol (flubendazole) in feed at 600 g/tonne of feed, equivalent to 30 g flubendazole (30 ppm) for 7 days. Note there is a 7‐day WHP for meat. Do not use in pigeons or parrots. |

| Cestodes (tapeworms) | Flubenol (flubendazole) in feed at 1200 g/tonne of feed, equivalent to 60 g flubendazole (60 ppm) for 7 days. Note there is a 7‐day WHP for meat. Do not use in pigeons or parrots | No alternative treatments |

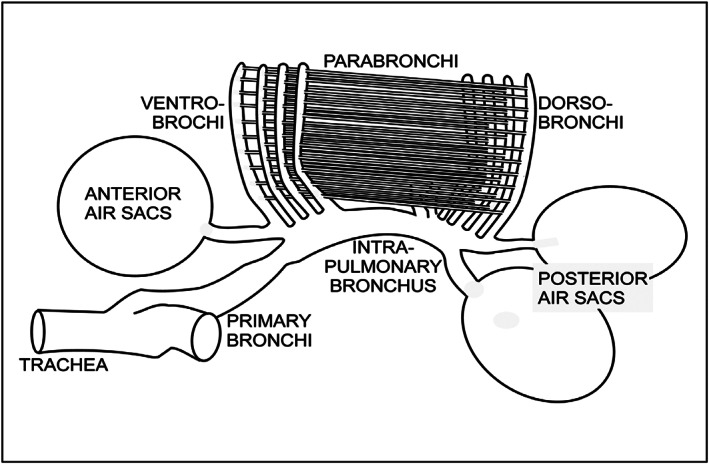

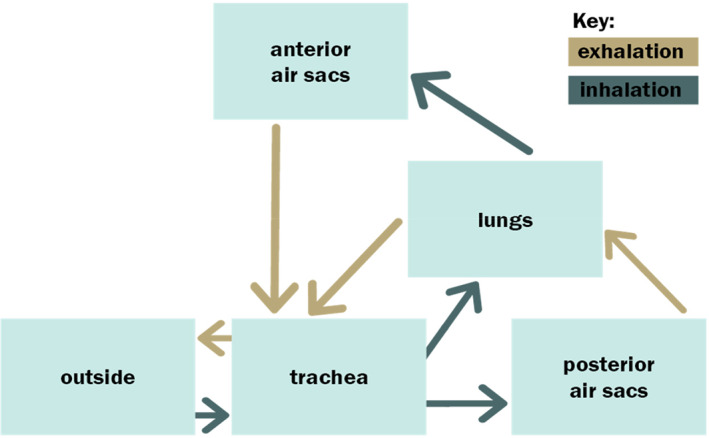

Diseases of the respiratory system