Background: Understanding SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among health care workers is important because they are at high risk for occupational exposure and may be convincing advocates for vaccination among their patients.

Objective: To determine the relationship between social and demographic characteristics of health care workers and receipt of vaccination.

Methods and Findings: We did a cross-sectional study of all employees of the MetroHealth System, an urban safety-net health care system that includes a main hospital, skilled-nursing and rehabilitation facilities, and ambulatory clinic locations across Northeast Ohio. Starting on 16 December 2020, MetroHealth administered vaccinations to its employees in a large, central location of the main hospital. Human resources files were used to identify work location and job title for all employees. We extracted information on age, sex, and self-reported race/ethnicity from electronic health records. Logistic regression was used to obtain unadjusted and marginally adjusted standardized probabilities of vaccination while accounting for employee demographic characteristics, occupational category, and COVID-19 test positivity. The study was approved by the MetroHealth Institutional Review Board.

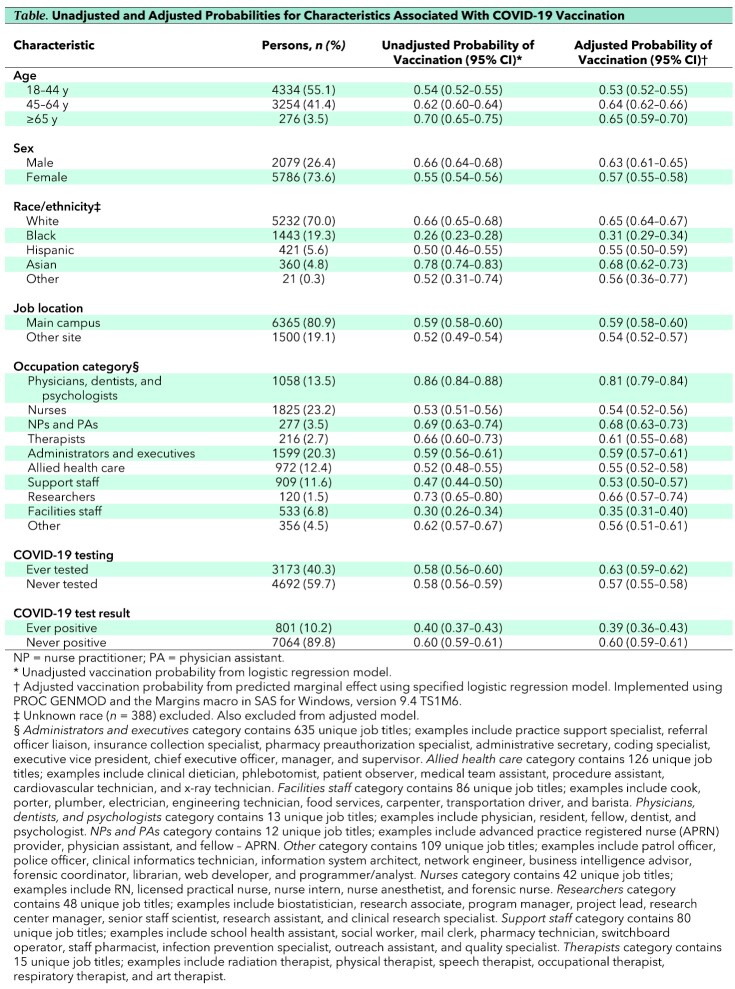

A total of 7865 employees were included in the study. The Table shows demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. Almost half (40.3%) had 1 or more SARS-CoV-2 tests recorded, and 801 persons had a positive result. During the period of observation, 4554 employees (57.9%) received the first dose of vaccine.

Table.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Probabilities for Characteristics Associated With COVID-19 Vaccination

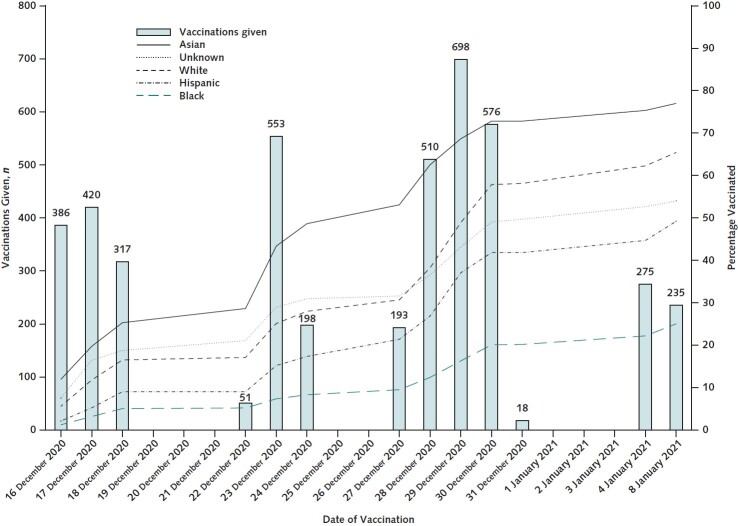

The Table also shows results of univariate and multivariable analyses. On multivariable analysis, the probability of being vaccinated was higher among employees older than 44 years, men, Whites, and Asians. The differences in the rate of vaccination by race and ethnicity increased over the period of vaccination (Figure). Employees who worked at the main hospital were more likely to be vaccinated. Physicians, dentists, and psychologists had the highest probability of being vaccinated, followed by nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Clinical nurses, support staff, and facilities workers were the least likely to undergo vaccination. Employees who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 were more likely to be vaccinated. However, among tested employees, those who tested positive were less likely to be vaccinated.

Figure. Number and percentage of vaccinations over time, by race and ethnicity.

Discussion: We found sizeable disparities in vaccination rates by race/ethnicity and occupational category. Our findings of decreased vaccination among Black and Hispanic persons are concerning given the high burden of COVID-19 affecting these communities (1, 2). The low vaccination rate among nurses is also concerning given their higher rate of occupational exposure to SARS-CoV-2 and likely higher risk for death due to COVID-19 (3). Although vaccination rates improved among all racial and ethnic groups over time, the differences between those groups widened.

Many of the barriers to vaccination that are commonly cited (4) were absent in this study. The availability, efficacy, and safety of the vaccines were widely publicized to all employees by e-mail, intranet, flyers posted on bulletin boards, and word of mouth. Vaccination scheduling could occur at any time via patient portal or by telephone. Many dates and times were available to choose from. The vaccines were provided free of charge at the main hospital. To encourage others to receive a vaccine, personal narratives from a diverse group of employees detailing their reason for being vaccinated and their vaccination experience were posted on the intranet alongside pictures of the authors. Despite these advantages, employees who worked away from the main campus were less likely to receive a vaccine. This suggests additional barriers to vaccination that should be identified and addressed in future work.

Our study's findings should be considered in concert with its limitations. Our study was done in a single, albeit large, health care system in the Midwest. Whether similar patterns are present in other systems or regions of the country is unclear. Because of the study design, we could not determine specific reasons for the differences in vaccination rates. We did not examine the relationship between having comorbid conditions and receiving the vaccine. The degree to which employees were aware of opportunities for vaccination is unclear.

Vaccination rates of health care system employees during the COVID-19 pandemic were less than ideal, particularly among certain groups at high risk for occupational exposure. Further work is needed to improve vaccination rates of health care system employees.

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 15 June 2021.

References

- 1. Lee FC , Adams L , Graves SJ , et al. Counties with high COVID-19 incidence and relatively large racial and ethnic minority populations — United States, April 1–December 22, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:483-489. [PMID: ] doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ.. No populations left behind: vaccine hesitancy and equitable diffusion of effective COVID-19 vaccines [Editorial]. J Gen Intern Med. 2021. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06698-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jackson D , Anders R , Padula WV , et al. Vulnerability of nurse and physicians with COVID-19: monitoring and surveillance needed [Editorial]. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:3584-3587. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1111/jocn.15347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schumacher S , Salmanton-García J , Cornely OA , et al. Increasing influenza vaccination coverage in healthcare workers: a review on campaign strategies and their effect. Infection. 2021;49:387-399. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01555-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]