In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the American College of Physicians' Scientific Medical Policy Committee began developing “practice points” to provide clinical advice based on the best available evidence for the public, patients, clinicians, and public health professionals. This article describes the methods for initial development and subsequent maintenance of rapid, living practice points—a process recently established to provide evidence-based responses to highly targeted, pressing clinical questions related to COVID-19.

Abstract

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Scientific Medical Policy Committee (SMPC) of the American College of Physicians (ACP) began developing “practice points” to provide clinical advice based on the best available evidence for the public, patients, clinicians, and public health professionals. As one of the first organizations in the United States to develop evidence-based clinical guidelines, ACP continues to lead and advance the science of evidence-based medicine by implementing new methods to rapidly publish practice points and maintain them as living advice that regularly assesses and incorporates new evidence. The overarching aim of practice points is to answer targeted key questions for which there is a timely need to synthesize evidence for decision making. The SMPC believes these methods can potentially be adapted to address various clinical and public health topics beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. This article presents an overview of the SMPC's living, rapid practice points development process, which includes a rapid systematic review, use of the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) method, use of stringent policies on the disclosure of interests and management of conflicts of interest, incorporating a public (nonclinician) perspective, and maintenance of the documents as living through ongoing surveillance and synthesis of new evidence as it emerges.

The Scientific Medical Policy Committee (SMPC) of the American College of Physicians (ACP) develops and disseminates clinical advice that addresses a wide range of clinical topics. The SMPC produces clinical advice via best practice advice (triggered by existing guidelines, systematic reviews, and practice- or knowledge-changing studies and based on a narrative review) and practice points (based on a rapid systematic review and typically maintained as living [continually updated] advice). This article describes the SMPC's methods for initial development and subsequent maintenance of living, rapid practice points—a process that the SMPC recently established to provide evidence-based responses to highly targeted, pressing clinical questions related to COVID-19. The foundational principle of ACP practice points is that they are based on scientific evidence gathered through an independent, rapid systematic review and methodologically rigorous approaches to ensure the development of trustworthy clinical advice. The SMPC plans to continue to implement these methods across a wider range of topics related to the health of individuals and populations beyond the questions related to the transmission, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of COVID-19.

Scientific Medical Policy Committee

ACP convenes a standing SMPC that works with ACP's Clinical Policy team to develop and disseminate advice that is intended to improve the health of individuals and populations and to promote high-value care on the basis of the best available evidence. All members of the SMPC, including the chair and the vice chair, are appointed by ACP's Board of Regents (ACP's governing body) and serve a 1-year term, which is renewable for a maximum of 4 years. Nomination and appointment to the SMPC follow the standard ACP procedures for selection of committee members by the ACP. The SMPC formally meets 3 times per year, of which 1 time is typically in person, and most of the work is done via conference calls or e-mails.

SMPC Members

The SMPC consists of a multidisciplinary group of 12 members. Eleven are internal medicine physicians representing expertise in clinical areas, epidemiology, health policy, and evidence synthesis. All physicians on the SMPC must be current ACP members. There is also 1 public (nonphysician) member with equal standing and terms as the physician members, including voting and authorship privileges. Recruited through an open application call via various informal and formal patient and professional networks, the public member provides a layperson perspective on values and preferences rather than disease-specific experiences.

Clinical Policy Team

The development of the practice points is a collaborative effort between the SMPC and ACP's Clinical Policy team. In addition to contributing clinical, scientific, and methodological expertise, the Clinical Policy team provides administrative support and liaises among the SMPC, evidence review teams, systematic review funding entities, and journals.

SMPC Subgroup

A subgroup of SMPC members, including the chair or vice chair, is assigned to each practice point topic. The subgroup works with the Clinical Policy team to draft and refine the key questions and lead the development of the practice points. The SMPC may also choose to invite external content experts to serve as subgroup members. The SMPC subgroup members are the primary authors of the published practice points. The subgroup works over conference calls and e-mails to draft the manuscript. Once the subgroup approves the final draft of the manuscript, it then moves on to the full SMPC for approval.

Disclosure of Interests and Management of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The SMPC's policy for disclosure of interests and management of conflicts of interest follows the same process as ACP's Clinical Guidelines Committee policy (1). The policy emphasizes full, continuous disclosure of all health care–related interests for SMPC members, ACP staff, external content experts, and consultants as well as transparent assessment and management of conflicts of interest. Disclosures are collected, and potential conflicts of interests are managed on an individual basis for each publication. Conflicts are managed according to the level of conflict identified (high, moderate, or low), and persons may be recused from authorship, voting, or discussion pertaining to practice points (1). The SMPC's policy makes 1 modification to the Clinical Guidelines Committee's policy: The SMPC may engage content experts with moderate-level conflicts of interest to serve as authors of practice points, whereas only staff and committee members with no or low-level conflicts of interest may serve as authors. However, any content experts must be in a minority of the total number of authors of a practice points article. The rationale for this modification is that practice points are intended to provide clinical advice when direct evidence is limited, and content experts provide additional support and knowledge in interpreting limited or insufficient evidence as well as extrapolating from indirect evidence. Disclosures and conflict management summaries are posted publicly online, and a link to the summaries is included in the SMPC publications (www.acponline.org/about-acp/who-we-are/leadership/boards-committees-councils/scientific-medical-policy-committee/disclosure-of-interests-and-conflict-of-interest-management-summary-for-scientific-medical-policy).

Selection and Scope of Topics

The SMPC reviews topic nominations from SMPC members, ACP members, and governance on an ongoing basis. In selecting a topic, the SMPC prioritizes those that necessitate the rapid development of advice to inform decision making related to urgent individual and population health needs (2), and it also considers if there is current uncertainty or controversy, the relevance to practice, and the topic's potential effect on individual and population health outcomes. In scenarios where new evidence is quickly emerging and the results of active research may reasonably affect current conclusions or advice, the SMPC may also choose to maintain certain practice points topics as living (continuously updated) advice (3, 4).

The SMPC uses an informal consensus process that occurs primarily over e-mail and conference calls to discuss and select topics. Given that priorities for rapid advice may shift quickly, such as in rapidly evolving pandemic situations, topic prioritization occurs on a rolling basis.

Target Audience

The target audience for living, rapid practice points is all clinicians, patients, the public, and public health professionals.

SMPC Rapid Practice Points and Their Development Process

The SMPC ensures that rapid practice points meet methodological rigor and trustworthiness by accounting for the standards (5, 6) set forth by the Guidelines International Network and the National Academy of Medicine (previously called the Institute of Medicine) and voluntarily completes and posts standard reporting forms with each practice point in the Guidelines International Network library and on ACP's website. Rapid practice points, however, are not clinical guidelines (7). Rapid practice points are designed to provide interim, time-sensitive answers, based on the best available evidence, to pressing questions related to individual and public health. The Figure summarizes the development process and timeframes.

Figure. Overview of development and approval process for SMPC living, rapid practice points.

ACP = American College of Physicians; BOR = Board of Regents; ERT = evidence review team; KQ = key questions; PICO = population, intervention/exposure, comparison, outcome; SMPC = Scientific Medical Policy Committee; SR = systematic review.

Key Question Generation

Once a topic is selected, the SMPC and Clinical Policy team draft key questions. The Clinical Policy team then works with the SMPC subgroup and evidence review team to refine the key questions and draft population, intervention(s)/exposure(s), comparator(s), and outcome(s) (PICO) describing the clinical question of interest. After SMPC subgroup approval, the key questions and PICO are shared with the full SMPC for comment and final approval. All work related to key question generation is completed via e-mail or conference calls.

Rapid Systematic Review

All practice points are based on a rapid systematic review that is done by an independent evidence review team. The SMPC may nominate or use an existing systematic review through one of several sources: the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence-based Practice Center Program, the Veterans Affairs Evidence Synthesis Program, or another evidence-based program (for example, Cochrane). The Clinical Policy team and SMPC subgroup work with the evidence review team to determine appropriate evidence synthesis methods depending on the key question and on the basis of guidance for the conduct of systematic reviews and rapid reviews. To streamline the methods to achieve a rapid review, the SMPC may consider potential mechanisms like adjustments to the key questions (for example, narrowing the scope or outcomes) and limiting inclusion criteria (for example, types of indirect evidence, study design, and timeframe). Registration of the systematic review is at the discretion of the evidence review team.

Determining Certainty of Evidence

The evidence review team uses the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) method to rate the certainty of evidence for outcomes of interest, which incorporates factors beyond just the statistical significance of results (8). The certainty of evidence for each outcome is rated as high, moderate, low, or insufficient depending on the quality of studies, consistency of findings, precision of estimated effects, directness of the evidence to the key question of interest, and potential for publication bias. The evidence review team may also explicitly establish clinically meaningful effect thresholds to determine the certainty of evidence and the magnitude of effects for the outcomes considered.

Evidence Tables

The Clinical Policy team prepares evidence summary tables, appendix tables, and a figure derived from the rapid systematic review. For each outcome of interest, the evidence summary tables report the study designs, number of studies, total number of participants in studies, certainty of evidence, and effect size estimates (Table 1) (9). Appendix tables report the corresponding data associated with each outcome described in the evidence summary tables. A figure summarizes the characteristics of included studies and participant population details. The SMPC subgroup and SMPC review the evidence summary tables, data appendix tables, and figure when drafting, deliberating, and finalizing the practice points.

Table 1.

Effect Size Estimates: Descriptive Summary Statements

Developing and Finalizing Rapid Practice Points

In developing the rapid practice points, the SMPC assesses the balance of benefits and harms on the basis of the magnitude of effects and certainty of evidence and also considers public and patient values and preferences and other contextual considerations including, but not limited to, cost, acceptability, and feasibility. The SMPC subgroup works with the Clinical Policy team via e-mail and conference calls to draft the practice points and detailed rationales to describe the supporting evidence and additional factors being considered. Practice points also describe relevant clinical considerations for dissemination and implementation.

Addressing Insufficient Evidence

The SMPC highlights the findings as insufficient evidence in the evidence and appendix tables and in a separate table highlighting research gaps when the evidence is too uncertain to assess the effect on health outcomes or the net effects of an intervention.

Addressing No Evidence

The SMPC identifies areas of no evidence in the evidence and appendix tables and in a separate table highlighting research gaps when there are no studies that meet the inclusion criteria to evaluate interventions or outcomes of interest.

Review and Approval of Rapid Practice Points

SMPC Review

Members of the SMPC review the draft practice points, typically via e-mail or by conference calls, as needed. Although no formal consensus process is used, SMPC members comment and revise until they achieve consensus on the final version. If consensus is not achieved, the draft will go back to the SMPC subgroup for further discussion and revisions based on the SMPC's feedback.

SMPC Voting Policy

Only SMPC members participate in voting. A minimum of 75% agreement among eligible committee voters is required to approve the practice points. Voter eligibility is determined on the basis of conflicts of interest (1, 3). If the practice points are approved without unanimous agreement, any member who abstained or voted against final approval will be acknowledged in the final publication as nonauthor contributors, in accordance with guidance on authorship criteria from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (10). The SMPC does not publicly disclose individual voting records.

Internal Review Process

The practice points undergo final review and approval as ACP policy by or on behalf of the ACP Board of Regents.

External Peer Review Process

All ACP practice points undergo independent editorial and peer review via the target publication journal. The rapid systematic review first undergoes extensive peer review via the funding organization's standard process and is then submitted in parallel with the practice points to the target publication journal and undergoes a second independent editorial and statistical review process.

Maintaining Rapid Practice Points as Living Advice

Rapid practice points are typically based on evidence that is limited or evolving quickly, and the SMPC may plan to maintain some topics as living if there is a reasonable chance that the conclusions of the practice points may change or shift within a shorter timeframe (3). Maintenance of each topic as living is typically initially planned through 1 year from the initial search date. However, the SMPC will continuously assess the priority of the topic and the overall state of evidence and may choose to retire the topic early or extend maintenance beyond 1 year.

Living, Rapid Systematic Review: Process, Periodicity, and Versions

There are 3 components to maintaining the systematic review as living: rerunning literature searches to scan for new studies or maintaining a process for the evidence surveillance, publishing surveillance notices and reports, and publishing new versions. The evidence review team and SMPC assess and consider the anticipated rate of new evidence emerging to agree on intervals for searches, surveillance, and updates; thus, frequencies may vary depending on the specific topic. However, a typical strategy includes the following:

Searches are run on a recurring basis to identify new studies, screen for eligibility, and assess risk of bias.

Surveillance notices, surveillance reports, or new versions are typically published every 3 to 4 months.

If no new studies are identified, the evidence review team publishes a surveillance notice on the original report that indicates the date of the last search and that no new studies were identified.

If new studies are identified that do not change the previous conclusions, the evidence review team publishes a surveillance report that briefly describes the new findings, without updating the synthesis of the evidence.

If new studies are identified that change the previous conclusions (for example, overall certainty of evidence or direction of effect), the evidence review is fully updated as a new version, which includes a new synthesis of the evidence and concurrent modification of further considerations.

In addition, the SMPC may determine that shifting clinical circumstances warrants modification of the original key questions, because the whole process is living, and will request a full update of the evidence review.

Living, Rapid Practice Points Updating: Process, Periodicity, and Versions

The Clinical Policy team maintains ongoing communication with the evidence review team, and the SMPC monitors all surveillance notices, reports, or updates from the evidence review team.

If the evidence review team issues a surveillance notice indicating that no new studies were identified, the SMPC publishes a comment on the most recent version of the practice points that indicates the date of the last search and that no new studies were identified.

When new studies are identified, the SMPC reviews the evidence review team's assessment (surveillance report or plan for full update). The SMPC considers quantitative and qualitative factors such as, but not limited to, the certainty of the evidence, balance between benefits and harms, and contextual considerations when assessing if the new evidence leads to meaningful changes to its previous practice points. After this assessment, the SMPC takes one of the following actions:

1. Reaffirm the practice points. If the new evidence or contextual considerations do not lead to meaningful changes in the practice points, the SMPC will publish an update alert that reaffirms the current practice points. The SMPC may also use update alerts to modify the language rather than intent of the practice points, such as to improve readability.

2. Revise and modify the practice points. If the new evidence or contextual considerations lead to meaningful changes in the practice points, the SMPC will develop a new version of the practice points. The Clinical Policy team will work with the SMPC subgroup to revise the practice points following the same development and approval process as described earlier. The new version, titled version 2, version 3, and so on, references all preceding practice points versions and update alerts.

Update alerts and new versions will indicate the date of the last search, provide a summary of the new evidence, and update the existing rationale and evidence tables to incorporate the new evidence as well as relevant contextual considerations. All update alerts and practice points versions are indexed on ACP's website (www.acponline.org/clinical-information/guidelines).

Retirement From Living Status

At any time, as a result of the living searching, surveillance, and updating process, the SMPC may determine that a topic does not require further updates and, therefore, decide to retire the publication from living status. This may happen when the topic is no longer considered a priority for decision making, when there is confidence that the conclusions are not likely to change with the emergence of new evidence or affect the practice, or when it is unlikely that new evidence will emerge (3). On retirement of a topic from living status, the SMPC will publish an update alert in the journal reporting the change in status along with a brief rationale.

Publication and Dissemination

All ACP practice points are submitted for publication in a high-impact, peer-reviewed journal. Links to the articles can be found on ACP's website at www.acponline.org/clinical-information/guidelines. In addition to journal publication and website posting, the practice points may be presented at ACP's annual meeting, announced in ACP newsletters, and covered by national media stories. The ACP practice points are also submitted to the Guidelines International Network library.

Financial Support

Financial support for the development of ACP practice points comes exclusively from ACP's operating budget. ACP staff and consultants who author the practice points receive no additional compensation for the development of the articles, apart from their wages or salary, which comes out of the ACP operating budget. No industry funding is accepted for any stage of development. Members of the SMPC do not receive any honoraria except for reimbursement for travel-related costs for any in-person work, which comes out of ACP's operating budget. The accompanying rapid systematic reviews are typically funded by a public entity (for example, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or Veterans Administration).

Discussion

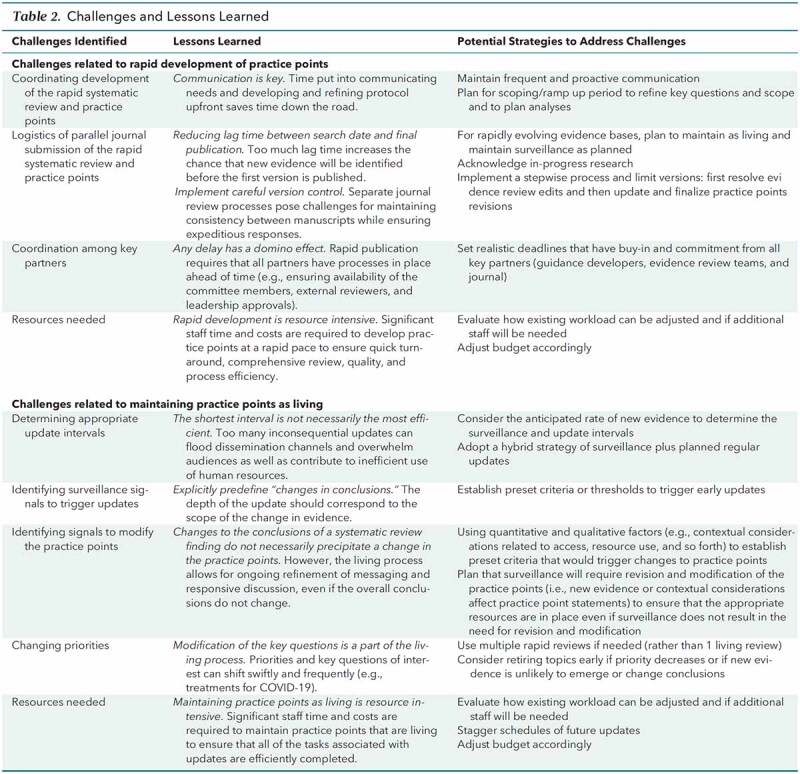

With the overall objective of highlighting timely, pressing issues that will have wide-reaching effects for clinicians, patients, and populations, the SMPC develops living, rapid practice points to provide easy-to-digest, high-level summaries accompanied by clinical advice based on the best available evidence. This article describes the SMPC's methods for the development of living, rapid practice points, as piloted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The development of living, rapid practice points has proven to be resource intensive, and during the course of the pilot, the SMPC identified many challenges and lessons learned (Table 2). Identifying innovative strategies to address these challenges is key to developing a sustainable rapid response program that can contribute to addressing new topics within and beyond the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Such new topics could include emerging technologies with rapid uptake (such as genetic testing and wearable heath devices and technology) or other types of population health epidemics (such as use of electronic cigarettes among young persons). As the SMPC continues to refine and advance its methods for living, rapid practice points, future methods updates will focus on optimizing efficiency, ensuring that appropriate resources are in place, and evaluating the dissemination of the practice points.

Table 2.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 25 May 2021.

* This paper, written by Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MHA; Jennifer Yost, RN, PhD; Mary Ann Forciea, MD; Janet A. Jokela, MD, MPH; Matthew C. Miller, MD; Adam Obley, MD; and Linda L. Humphrey, MD, MPH, was developed for the Scientific Medical Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Individuals who served on the Scientific Medical Policy Committee from initiation of the project until its approval were Linda L. Humphrey, MD, MPH (Chair)‡; Robert M. Centor, MD (Vice Chair)‡; Elie A. Akl, MD, MPH, PhD†; Rebecca Andrews MS, MD‡; Thomas A. Bledsoe, MD‡; Mary Ann Forciea, MD‡; Ray Haeme‡§; Janet A. Jokela, MD, MPH‡; Devan L. Kansagara, MD, MCR‡; Maura Marcucci, MD, MSc‡; Matthew C. Miller, MD‡; and Adam Jacob Obley, MD‡. Approved by the ACP Board of Regents on 7 November 2020.

† Nonauthor contributor.

‡ Author.

§ Nonphysician public representative.

References

- 1. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Disclosure of interests and management of conflicts of interest in clinical guidelines and guidance statements: methods from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:354-361. [PMID: 31426089] doi: 10.7326/M18-3279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kowalski SC, Morgan RL, Falavigna M, et al. Development of rapid guidelines: 1. Systematic survey of current practices and methods. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16:61. [PMID: 30005712] doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0327-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akl EA, Meerpohl JJ, Elliott J, et al; Living Systematic Review Network. Living systematic reviews: 4. Living guideline recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91:47-53. [PMID: 28911999] doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guidance for the production and publication of Cochrane living systematic reviews: Cochrane Reviews in living mode. Version December 2019. Accessed at https://community.cochrane.org/sites/default/files/uploads/inline-files/Transform/201912_LSR_Revised_Guidance.pdf on 14 September 2020.

- 5. Graham R, Mancher M, Miller D, et al, eds; Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. National Academies Pr; 2011. [PubMed]

- 6. Qaseem A, Forland F, Macbeth F, et al; Board of Trustees of the Guidelines International Network. Guidelines International Network: toward international standards for clinical practice guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:525-31. [PMID: 22473437] doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Lin JS, et al; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. The development of clinical guidelines and guidance statements by the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians: update of methods. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:863-870. [PMID: 31181568] doi: 10.7326/M18-3290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schünemann H, Broz˙ek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, eds. GRADE Handbook. Updated October 2013. Accessed at http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/app/handbook/handbook.html on 27 Aug 2020.

- 9. Santesso N, Glenton C, Dahm P, et al; GRADE Working Group. GRADE guidelines 26: informative statements to communicate the findings of systematic reviews of interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;119:126-135. [PMID: 31711912] doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Defining the role of authors and contributors. Accessed at www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html on 27 August 2020.