Background: The COVID-19 pandemic, which has resulted in more than 142 million cases globally, has challenged health care systems to rapidly transform care to address complex and dynamic resource demands (1, 2). Early in the pandemic, our large integrated health system implemented the Atrium Health Hospital at Home (AH-HaH) program to deliver home-based, hospital-level care to patients with COVID-19 and increase the health system's bed capacity (3).

Objective: To determine which AH-HaH patients were at increased risk for care escalation to traditional brick-and-mortar facilities.

Methods and Findings: We conducted a retrospective cohort study to follow up on adults (aged ≥18 years) who received treatment for COVID-19 in the AH-HaH program between 23 March and 29 November 2020. The program and eligibility criteria have been described previously; briefly, patients who the evaluating provider would otherwise have admitted to the brick-and-mortar facility who had safe living situations and clinical stability at admission (normal mental status, vital signs and oxygen saturation suitable for home monitoring, receiving ≤4 L of supplemental oxygen per minute, and no anticipated imaging or invasive procedures within 48 hours) were eligible (3). AH-HaH care included 24/7 telephonic access to nurses; at least daily in-home visits from paramedics; daily virtual visits with a hospitalist; and therapies that included intravenous fluids and antibiotics, noninvasive oxygen, and respiratory medications as needed. We examined patients admitted from ambulatory care, emergency departments, or community settings to AH-HaH within 14 days of an initial positive result on a COVID-19 test. We collected baseline covariates (for example, sociodemographic characteristics, coexisting conditions, and worst vital signs at AH-HaH admission) and treatment information from electronic health records. The Area Deprivation Index, a composite measure of area-level social determinants of health, was calculated at the census tract level for each patient. The primary outcome was direct transfer to an Atrium Health brick-and-mortar facility (inpatient or observation status) within 14 days of index AH-HaH admission. We conducted logistic regression to test the association between baseline covariates and the primary outcome. In a secondary analysis, we applied descriptive statistics to explore characteristics of patients who had immediate (≤48 hours) and nonimmediate (>48 hours) care escalation.

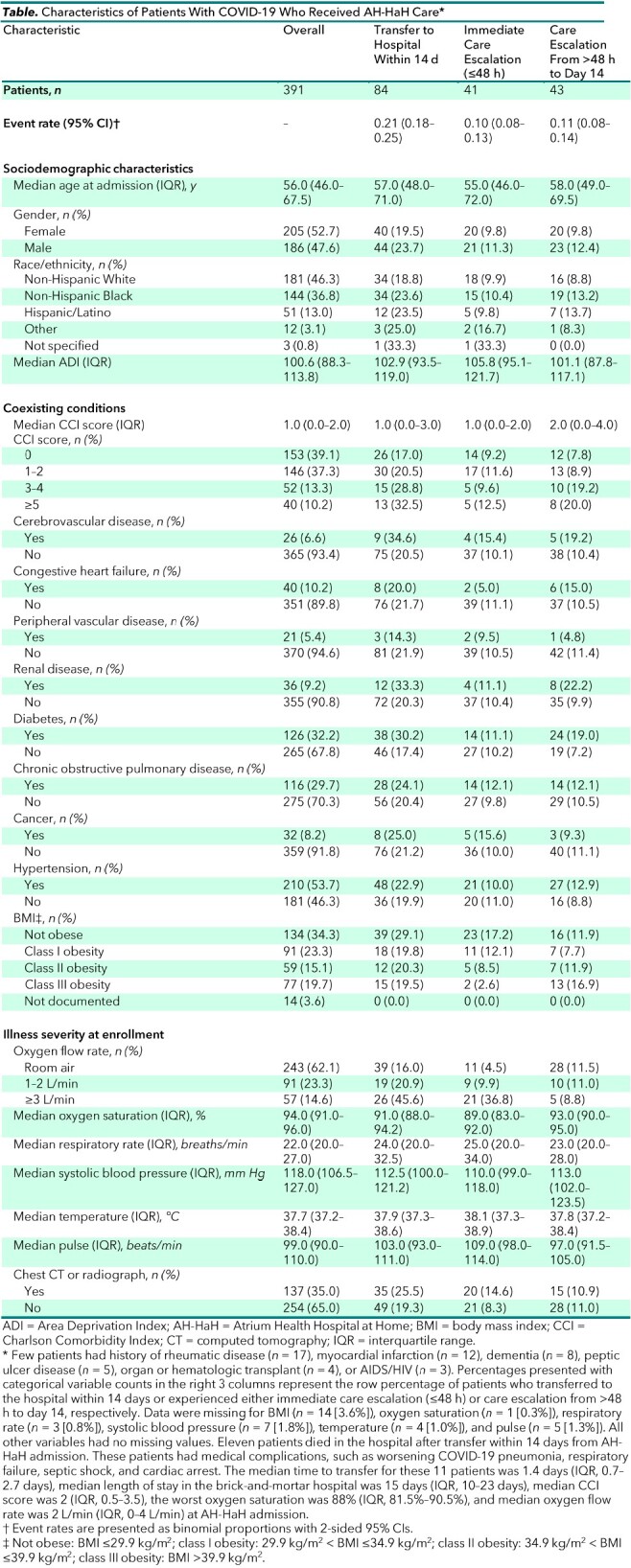

There were 391 eligible patients, 53% of whom were female and 46% of whom were White, with a median age of 56 years (Table). The median length of AH-HaH stay was 3 days (interquartile range, 1 to 5 days). Eighty-four patients (21%) were transferred to a brick-and-mortar facility within 14 days (median time to transfer, 2.2 days [interquartile range, 0.8 to 3.3 days]). Among hospital admissions, 33 required intensive care, 11 required mechanical ventilation, and there were 11 in-hospital deaths (causes included organ failure and shock). In multivariable analysis (Figure), higher oxygen saturation was associated with decreased odds of transfer (odds ratio, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.81 to 0.93]), whereas higher comorbidity burden was associated with increased odds of transfer (odds ratio, 1.12 [CI, 0.99 to 1.26]). In the secondary analysis, respiratory aberrations (such as low oxygen saturation, supplemental oxygen ≥3 L/min, and high respiratory rate) and tachycardia at enrollment were frequently observed among patients who required immediate care escalation, whereas high-risk chronic conditions (such as hypertension and diabetes) were common among patients who required nonimmediate care escalation.

Table. Characteristics of Patients With COVID-19 Who Received AH-HaH Care.

Figure. Forest plot of the associations between patient characteristics at Hospital at Home admission and transfer to a brick-and-mortar facility within 14 days.

The point estimate for each OR is represented by a black square, with the 95% CI represented by a horizontal line. Eighteen observations (4.6%) were excluded from the model because of missingness in ≥1 of the covariates. The Hispanic/Latinx, “other,” and “not specified” racial/ethnic groups were combined because of the small numbers of persons in each group. ADI = Area Deprivation Index; BMI = body mass index; CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; OR = odds ratio.

Discussion: Home-based hospital care is an attractive innovation that may extend critical hospital resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that most patients did not require care escalation, with approximately 1 in 5 admitted within 14 days. We observed more severe respiratory involvement among transferred patients, particularly those requiring immediate care escalation. In addition, overall comorbidity burden was associated with transfer, similar to previous studies describing underlying conditions as important risk factors for severe COVID-19 illness (4). Conversely, we did not observe independent associations between older age or obesity and transfer. This unexpected finding may be due to providers being more cautious about enrolling older or obese persons with additional high-risk characteristics into AH-HaH. Although not statistically significant, race/ethnicity and area-level deprivation warrant additional research given established COVID-19 health disparities and possible bias due to home-based AH-HaH eligibility criteria (5).

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of the retrospective, single-center design utilizing outcomes occurring within Atrium Health, the modest sample size that may limit identification of significant risk factors for care escalation, and the potential for differences between reasons for index admission and care escalation (such as unrelated trauma or illness). Nevertheless, this study provides practical initial evidence to help inform patient selection guidelines as health systems and payers increasingly leverage hospital-at-home as a standard care delivery option.

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 11 May 2021.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. 2021. Accessed at www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 on 21 April 2021.

- 2. Ranney ML , Griffeth V , Jha AK . Critical supply shortages – the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e41. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2006141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sitammagari K , Murphy S , Kowalkowski M , et al. Insights from rapid deployment of a “virtual hospital” as standard care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:192-9. [PMID: ]. doi: 10.7326/M20-4076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wynants L , Van Calster B , Collins GS , et al. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of covid-19 infection: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ. 2020;369:m1328. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berkowitz SA , Cené CW , Chatterjee A . Covid-19 and health equity – time to think big. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:e76. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2021209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]