Abstract

Background

Vending machines represent one way of offering food, but they are overlooked in the efforts to improve people’s eating habits. The aim of our study was to analyse the variety and nutritional values of beverages offered in vending machines in social and health care institution in Slovenia.

Methods

The available beverages were quantitatively assessed using traffic light profiling and the model for nutrient profiling used by Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Vending machines in 188 institutions were surveyed, resulting in 3046 different beverages consisting of 162 unique product labels.

Results

Between 51 and 54% of beverages were categorised as unhealthy with regard to sugar content. Water accounted for only 13.7% of all beverages in vending machines. About 82% of beverages in vending machines were devoted to sugar-sweetened beverages, the majority (58.9%) presented in 500-ml bottles. The average sugar content and average calories in beverages sold in vending machines are slightly lower than in beverages sold in food stores.

Conclusions

We suggest that regulatory guidelines should be included in the tender conditions for vending machines in health and social care institutions, to ensure healthy food and beverage choices.

Keywords: Beverages, Vending machines, Social care institutions, Health care institutions, Slovenia

Background

Vending machines usually carry snacks and beverages of low nutritional value, but high in calories, fats, salt and sugar [1, 2], whereas healthy options are hardly offered or totally absent [3, 4]. Considering that such options are available in social and health care institutions, unhealthy dietary choices are available to medical and hospital personnel working long hours, patients, residents and visitors. This is contrary to the World Health Organization (WHO) vision of hospitals that should contribute to building a stronger health system and a healthy community [5]. As hospitals matter to people [5], should they not be a model of offering healthy dietary choices in their vending machines? If alcohol and tobacco products are not sold in health care institutions, why do they offer unhealthy dietary choices?

Beverages with added free sugars represent a major share of the available beverages in vending machines [6, 7]. Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses of cohort studies and randomized clinical studies demonstrated that drinking sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) increases not only the risk for weight gain and obesity, but also the risk for tooth decay (caries), type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, impaired nutrition and several other adverse health effects [8–15]. Especially worrisome are obesity and type 2 diabetes, as they emerged as epidemics of modern societies [16, 17]. On the global level, WHO tackles this problem in the Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases in the WHO European Region 2016–2025 [18], whereas on the local level, Slovenia’s National Assembly adopted the “National Program on Nutrition and Health Enhancing Physical Activity 2015–2025” which is coordinated by the Ministry of Health. One of its ten priority areas is the role of health care for maintaining health and for preventing chronic diseases and obesity. Proper nutrition, physical activity and healthy diet choices provided to patients, staff and visitors in health and social care institutions are emphasised as a prerequisite for successful treatment [19].

Increasing numbers of studies show that a well-designed graphic, i.e. traffic light labelling, on the front of food packages, can provide consumers with quick and clear summarised information on nutritional quality and help them to compare products to make healthier choices. Traffic light labelling was first introduced by the Food Standards Agency in the UK in 2007, but the threshold values for categories have changed multiple times since then [20]. There is currently no international consensus about the broadly acceptable standardized nutritional profile model that could be used for front-of-pack summaries of the nutritional quality of foods. Australia and New Zealand show best practise in policy implementation in this area that could be followed by other countries. They use the Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) Nutrient Profiling Scoring Criterion model [21] to determine the eligibility of foods and beverages to carry health claims, meaning that only foods with better nutritional quality are allowed to carry health claims. A recent study in Slovenia [22] also evaluated the nutritional quality in food supplies based on the FSANZ model and found that 50% of available beverages in food stores are of lower nutritional quality. The aim of our study was to analyse the variety and nutritional quality of beverages available in vending machines placed in social and health care institution in Slovenia. The resulting guidelines for providing healthier choices for hospital workers, patients and visitors could also support future regulatory interventions.

Methods

Sample

Our sample consisted of vending machine displays in all Slovenian hospitals (26), community health centres (64) and all but one nursing homes (98 out of 99), with one exception due to withheld data. The survey was carried out between June and August 2018. All accessible vending machines in each facility were surveyed. The collected data was based on face-front items, i.e. the item in the vending machine slot that was next in line to be sold [1]. If there were five or more empty places of products in a vending machine at the time of the survey, the data collection was repeated on another occasion. Vending machine displays in 188 institutions resulted in 5625 face-front items, with beverages accounting for 54.2% (n=3046) items and consisting of 162 unique product labels.

Product categorisation

Each beverage was categorised based on the content of sweeteners, and further subcategorised according to the type of beverage [23] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Beverage categorisation

| Category | N (%) | Subcategory |

|---|---|---|

| Soft drinks | 2286 (75.0) | Carbonated beverages with sugar, carbonated drinks with no sugar and added aspartame/acesulfame-k sweetener, non-alcoholic beer, non-carbonated beverages with sugar, sugar-tasting water, water with taste but no sugar |

| Waters | 417 (13.7) | Mineral water, water |

| Coffee | 119 (3.9) | Iced coffee |

| Juices | 113 (3.7) | 100% natural juice, smoothie |

| Energy drinks | 111 (3.6) | Energy drinks with no sugar and added aspartame/acesulfame-k sweetener, energy drinks with sugar |

Nutrient profiling

For each product, nutritional data labelled on beverages, such as fat, saturated fatty acids, sugars, sodium, salt, protein, fibre, energy value and proportion of fruits and vegetables stated in the ingredient list were used. Each product was categorised according to average fat, saturated fatty acid, sugar, and salt values per 100 ml with dietary traffic light labelling (Table 2) as a quality indicator. In the current survey, we used the threshold values listed in Table 2, which are implemented in Slovenia in a variety of programmes for facilitating healthy food choices, such as in the government-funded smart mobile application VesKajJes [24] and the purpose of examining the displays in vending machines at selected Slovenian faculties by the Consumer Association of Slovenia. Green means low content of critical nutrients, while red indicates high content of such constituents [25].

Table 2.

Criteria for traffic light labelling of beverages in Slovenia

| Quality indicator | Green | Amber | Red |

|---|---|---|---|

| [g/100 mL] | |||

| Fat | < 1.5 | 1.5–10 | > 10 |

| Saturated fatty acids | < 0.75 | 0.75–2.5 | > 2.5 |

| Sugar | < 2.5 | 2.5–6.3 | > 6.3 |

| Salt | < 0.3 | 0.3–1.5 | > 1.5 |

To compare the nutritional quality of the displayed items in vending machines to the displays in stores with the Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) [21], the Nutrient Profiling Scoring Criterion FSANZ model was used. This is a scoring model; foods receive positive and negative points for energy, key nutrients and constituents, and there are different (sum) score thresholds for three types of products (beverages, foods and fats and cheese with high calcium content). For this study, foods that did not pass the FSANZ criterion were considered as less healthy. A similar approach was used in a recent assessment of the nutritional quality of foods available in Slovenian food supplies [22] and in vending machines in health and social care institutions in Slovenia [26].

Statistics

Descriptive statistics expressed as averages with standard deviation (SD) or percentages were used in data analysis. Additionally, percentages of beverages categorised with dietary traffic light labelling were shown, which served as overall quality indicator of the displays in hospitals, community health centres and nursing homes.

Results

Altogether, 188 institutions were surveyed, of which 134 had at least one food/beverage vending machine on their premises. No vending machines were present in 7.7% hospitals (2 out of 26), 12.5% community health centres (8 out of 64) and 44.9% nursing homes (44 out of 98). From the total of 5625 products found in the vending machines, 54.2% (n=3046) products were beverages and were further investigated in this study. The analysis excluded products from non-standard vending machines, e.g. freshly squeezed orange juice or warm beverage vending machines.

When looking at beverages displayed in different types of institutions, 26.9% (n=819) beverages were from hospital vending machines, 36.8% (n=1120) from community health centre vending machines and 36.3% (n=1107) from vending machines placed in nursing homes. Beverages amounted to slightly more than half, i.e. 54.2% (n=3046) of the products in vending machines, which varies depending on the type of institution, with 51.7% in hospitals, 52.8% in community health centres and 57.4% in nursing homes.

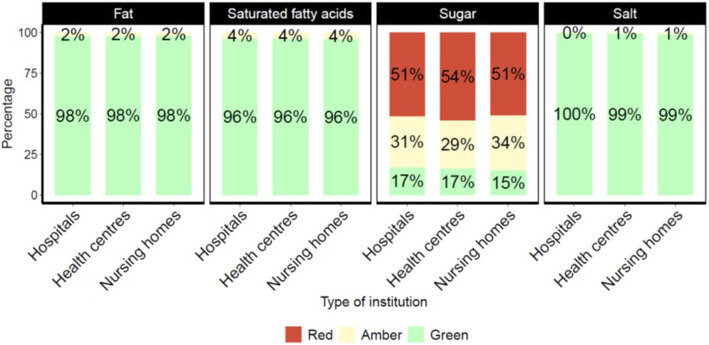

Overall quality indicators for fat content, saturated fats, sugars and salts showed that the main problem in beverages sold in vending machines were sugars; considering traffic light profiling, between 51 and 54% of beverages fall into the red category. This is followed by the amber category regarding the sugar content (for 29–34% of beverages). Only 15 to 17% of beverages have been assigned a green category for the sugar content (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percentage (%) of beverages in the vending machines in health and social care institutions categorised into green/amber/red (traffic light profiling)

As seen in Table 3, 82.3% out of 3046 beverages in vending machines were devoted to sugar-sweetened beverages. Smoothies accounted for only 0.4% and 100% juice for only 3.3% of beverages sold in vending machines. Out of 134 locations, smoothies were found at only five different locations, and 100% juices at only 51 different locations. Water accounted for only 13.7% of the beverages, available in vending machines. A more detailed overview of results where additional subcategories with average calories, sugar content and results of nutrient profiling using the FSANZ model are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Average calories and sugar content of beverage categories with FSANZ model nutrient profiling

| Average from all health and social care institutions (n=188) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total share in relation to all beverages listed [%] | Average calories [kcal in 100 mL] | Average sugar content [in 100 mL] | FSANZ | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | (% less healthy products) | ||

| Beverage categorisation | ||||||

| Soft drinks | 75 (n=2286) | 30.3 | 14.64 | 7.5 | 4.75 | 66.4 |

| Waters | 13.7 (n=417) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Coffee | 3.9 (n=119) | 66.3 | 3.96 | 8.7 | 0.66 | 99.2 |

| Juices | 3.7 (n=113) | 42.2 | 17.58 | 8.6 | 3.42 | 14.2 |

| Energy drinks | 3.6 (n=111) | 45.7 | 6.03 | 10.8 | 1.48 | 98.2 |

| Beverage subcategorisation | ||||||

| Non-carbonated beverages with sugar | 30.3 (n=924) | 33.6 | 14.37 | 7.9 | 2.13 | 87.0 |

| Carbonated beverages with sugar | 23.1 (n=704) | 39.2 | 9.99 | 10.8 | 6.3 | 100.0 |

| Sugar-tasting water | 18.6 (n=568) | 18 | 4.47 | 4 | 0.38 | 0.0 |

| Mineral water | 8 (n=243) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Water | 5.7 (n=174) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Iced coffee | 3.9 (n=119) | 66.3 | 3.96 | 8.7 | 0.66 | 99.2 |

| Energy drinks with sugar | 3.6 (n=109) | 46.5 | 0.34 | 11 | 0.11 | 100.0 |

| 100% natural juice | 3.3 (n=102) | 40.4 | 16.96 | 8.4 | 3.38 | 15.7 |

| Carbonated drinks with no sugar and added aspartame/acesulfame-k sweetener | 1.4 (n=43) | 0.3 | 0.13 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Water with taste but no sugar | 1 (n=31) | 2.3 | 0.16 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Non-alcoholic beer | 0.5 (n=16) | 19.4 | 9.15 | 4.5 | 2.06 | 56.2 |

| Smoothie | 0.4 (n=11) | 58.8 | 14.84 | 10.9 | 3.1 | 0.0 |

| Energy drinks with no sugar and added aspartame/acesulfame-k sweetener | 0.1 (n=2) | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

According to nutrient profiling using the FSANZ model, about 60% (n=1760) of all beverage front-face items available in vending machines can be considered as lower nutritional quality. Iced coffee and energy drinks present product categories with lower nutritional quality by FSANZ (99.2–98.2% of products), especially because of high sugar content and energy density, as well as absence of any beneficial nutrients. Among soft drinks, non-carbonated beverages contain slightly less sugar and less calories as carbonated beverages on average. Therefore, 13% of non-carbonated beverages, out of the whole sample, were evaluated as healthy by the FSANZ model, while another 87% and all 100% of carbonated beverages were evaluated as unhealthy. However, the minority of 100% natural juices are evaluated as less healthy (15.7%) because of high percent of fruit present and no added sugar, but still being a relatively high-energy product. Similarly, smoothies were evaluated as healthy due to their higher fruit content, despite the naturally present sugar. Smoothies and iced coffee with added sugar are standing out as products with the highest average calories per 100 ml, but a FSANZ evaluation is indicating major differences. While smoothies are high-calorie products at the expense of natural sugar present from fruits, iced coffee is considered high calorie because of added sugar (average 8.7 g/100 ml) and therefore 99.2% of iced coffee products are evaluated as less healthy. It should be noted that according to the FSANZ model, all non-sweetened beverages and beverages with added sweeteners were identified as healthy products (Table 3).

Also of note is that soft drinks offered in vending machines in health and social care institutions are displayed in 500-ml bottles in almost 60% of displays (Table 4).

Table 4.

Size of packaging for beverages available in vending machines in health and social care institutions (n beverages= 3046)

| Beverages category | Size of packaging [mL] | |

|---|---|---|

| 0.2–0.35 [%] | 0.5 [%] | |

| Soft drinks | 16.11 (n=491) | 58.93 (n=1795) |

| Waters | 0 (n=0) | 13.69 (n=417) |

| Coffee and tea | 3.91 (n=119) | 0 (n=0) |

| Juices | 3.71 (n=113) | 0 (n=0) |

| Energy drinks | 3.09 (n=94) | 0.56 (n=17) |

| Total share [%] | 26.82 (n=817) | 73.18 (n=2229) |

Discussion

When comparing beverage products from vending machines in different health and social care institution (hospital, community health centre, nursing home), the results do not significantly differ between the various institutions. We can estimate that the availability of beverages, as well as the nutritional quality of the beverages, is quite similar. In this study, we found that 56% of all beverage front-face items available from vending machines is of lower nutritional quality. This proportion is slightly higher when compared to the beverages available in the Slovenian food supply, where 50% was shown in a previous study [22]. A recent international comparison [23] showed considerable potential for improving nutritional quality for beverages. Slovenia was in the bottom third with lower nutritional quality for beverages and average sugar content of 7.5 g and 170kJ per 100 ml [23]. The average sugar content and average calories in beverages sold in vending machine are slightly lower when compared with an average sugar content of 6.7 g and 120 kJ per 100 ml in beverages sold in food stores. Beverages with no sugar and with non-sugar sweeteners are evaluated as healthier by FSANZ; however, this is in contradiction with the WHO nutrient profile model [27], which does not support the addition of non-sugar sweeteners to beverages. The most notable problem in displayed beverages is a very high free sugar content. This is not in line with the scientific opinions of several eminent professional associations that claim that children, adolescents and adults should drink water or unsweetened tea instead of sugar-sweetened beverages and natural juices [8–11]. WHO guidelines recommend adults and children to reduce their daily intake of free sugars to less than 10% (roughly 50 g) of total energy intake, while the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and British recommendations (SACN) recommend less than 5% of total energy intake (3.5–9 g/day for children and adolescents aged 2–18 years). Compared to the results of our survey, the recommended daily intake of free sugars is nearly used when consuming only one average 500-ml carbonated beverage with free sugar. Although 100% natural juices seem like a healthy option, free sugar is naturally occurring and in liquid form (not added sugar) in those products, which, in addition to high intake, also affect the risk of developing obesity and non-communicable diseases [10]. When choosing one average sugar-sweetened beverage form a vending machine, containing approximately 140 kcal, the 5 to 7% of recommend daily calorie intake for an adult person and up to 12% of recommend daily calorie intake for small children [28] is already used.

Considering the increasingly popular vending machines and the trend of eating out [29–33], vending machines can be considered as an important environmental factor contributing to the obesity epidemic. Our results comply with the findings of other studies that snacks and drinks at vending machines located in various settings have limited healthy choices and high-energy and low-nutrient snacks are the first-choice options [1, 3, 4, 34–36]. In this context, vending machines represent a potential point of intervention for changing buyers’ eating habits to healthier choices [3]. Foods and beverages sold in vending machines are increasingly being scrutinized and addressed by federal policies. As a result, calls for local authorities to develop programs to promote healthier vending machines have been made overseas [8, 37–41]. The Slovenian School Nutrition Law [42] has prohibited vending machines in Slovenian primary and secondary schools since 2012. However, placing vending machines, as well as the nutritional values of available products in social and healthcare institutions, is not regulated by law. Thus, even those consumers who are aware of a healthy diet at the moment of choosing do not have the option of a healthy choice [36]. Healthier vending machine programs have already been implemented abroad in various settings such as hospitals [43], city parks [44], public buildings and government offices [45], and schools and university campuses [46–50]. Strategies that have already been used overseas mainly include enhancing healthier products on offer [43, 51–53] and changing prices and promoting healthier choices with posters, brands and stickers [3, 4, 54–57]. Since offering healthier options may be associated with shorter shelf life and higher product cost, an integrated approach is needed. Already available technical adaptations of vending machines as a refrigerated food vending may offer opportunity to have fresh healthy foods in vending, rather than having to rely on the limited range of pre-packaged items. In order to ensure acceptable product prices, the industry should be encouraged for product reformulation towards healthier options [58]. The general opinion that healthy food product is also more expensive is not necessarily correct [59]. In fact, research at vending machines across university campuses show that the difference between the prices of healthier and less healthy foods and beverages was $0.72 and $0.16, respectively, but these differences were not statistically significant [60]. Also, several countries in Europe have already introduced health-related taxes on specific foods with the objective of influencing what people are buying [61]. Overall, health should be prioritised over sales profit, and low-earning machines can be moved to high-traffic areas [58].

Another concern that should be highlighted is that the majority of beverages are displayed in plastic packaging, which contributes to the high carbon footprint of bottled water [62, 63]. Bottled water in Slovenia is also incomparably expensive compared with tap water [64]. Used once, the plastic packaging ends up at the waste collection centre (or even in nature), where in Slovenia, only 26% of plastics are recycled, mostly in downgrading processes [64, 65]. Approximately 36% of plastic packaging is re-used for energy by incineration [65], where toxic by-products, such as dioxins, are produced. Dioxins are toxic substances that show harmful effects on the skin and the immune system, are reproductive toxic and teratogenic, interfere with hormonal balance and are carcinogenic [66]. Plastics will, under environmental impacts, slowly degrade into microplastics, for which bioaccumulation and biomagnification processes through the food chain can cause concern for human health [67, 68]. As selling beverages in vending machines require packaging, the disadvantages of plastics could be addressed by introducing alternative materials for packaging, such as bioplastics [69], glass, metals or paper and paperboard [70, 71].

Conclusion

Based on the above findings, we propose that regulatory guidelines should be included in the tender conditions for vending machines in health and social care institutions to ensure healthy food and beverage choices.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

UR: substantial contributions to conception and design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation; drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. NFM, UPK, IP: substantial contributions to conception and design, data interpretation and critically revising the article. PK: substantial contributions to conception and design, data acquisition and analysis, and critically revising the article. MS: substantial contributions to conception and design, data interpretation. SST: substantial contributions to conception and design, final approval of the version to be published.

The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research was financially supported by the Ministry of Health of Republic of Slovenia as part of the implementation of the National Program on Nutrition and Physical Activity for Health 2015–2025, and by national research programme/project (P3-0395, L3-9290), funded by Slovenian Research Agency and Ministry of Health of Republic of Slovenia.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Urška Rozman, Email: urska.rozman@um.si.

Nataša Fidler Mis, Email: natasa.fidler@kclj.si.

Urška Pivk Kupirovič, Email: urska.pivk.kupirovic@nutris.org.

Igor Pravst, Email: igor.pravst@nutris.org.

Primož Kocbek, Email: primoz.kocbek@um.si.

Maja Strauss, Email: maja.strauss@um.si.

Sonja Šostar Turk, Email: sonja.sostar@um.si.

References

- 1.Byrd-Bredbenner C, Johnson M, Quick VM, Walsh J, Greene GW, Hoerr S, et al. Sweet and salty. An assessment of the snacks and beverages sold in vending machines on US post-secondary institution campuses. Appetite [Internet]. 2012 Jun [cited 2019 May 23];58(3):1143–51. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22414787 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Brown M V., Flint M, Fuqua J. The effects of a nutrition education intervention on vending machine sales on a university campus. J Am Coll Heal [Internet]. 2014 Oct 3 [cited 2019 May 23];62(7):512–6. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07448481.2014.920337 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Grech A, Allman-Farinelli M. A systematic literature review of nutrition interventions in vending machines that encourage consumers to make healthier choices. Obes Rev [Internet]. 2015 Dec 1 [cited 2019 May 23];16(12):1030–41. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/obr.12311 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Matthews MA, Horacek TM. Vending machine assessment methodology. A systematic review. Appetite [Internet]. 2015 Jul 1 [cited 2019 May 23];90:176–86. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666315001014?via%3Dihub [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.WHO. WHO | Hospitals in the health system. WHO [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 May 23]; Available from: https://www.who.int/hospitals/hospitals-in-the-health-system/en/

- 6.Zveza potrošnikov Slovenije. Projekt Študent – veš, kaj ješ (ŠTUDIRAM, HRANO PREMIŠLJENO IZBIRAM): Treba je znati izbrati [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug 23]. Available from: https://veskajjes.si/mediji/90-za-medije/projekt-student-ves-kaj-jes-studiram-hrano-premisljeno-izbiram-treba-je-znati-izbrati

- 7.Zveza potrošnikov Slovenije. Kaj ponujajo našim študentom v prodajnih avtomatih? - Tržni pregled prodajnih avtomatov s hrano in pijačo na štirih univerzah [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.zps.si/index.php/hrana-in-pijaa-topmenu-327/kakovost-ivil/7865-kaj-ponujajo-nasim-studentom-v-prodajnih-avtomatih-trzni-pregled-prodajnih-avtomatov-s-hrano-in-pijaco-na-stirih-univerzah-4-2016

- 8.Fidler Mis N, Braegger C, Bronsky J, Campoy C, Domellöf M, Embleton ND, et al. Sugar in infants, children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr [Internet]. 2017 Dec [cited 2019 May 27];65(6):681–96. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28922262 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Vos MB, Kaar JL, Welsh JA, Van Horn L V., Feig DI, Anderson CAM, et al. Added sugars and cardiovascular disease risk in children: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation [Internet]. 2017 May 9 [cited 2019 May 27];135(19). Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.WHO. Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children [Internet]. Guideline: sugars intake for adults and children. World Health Organization; 2015 [cited 2019 May 27]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25905159

- 11.SACN. Carbohydrates and health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 May 27]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sacn-carbohydrates-and-health-report

- 12.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després J-P, Hu FB. Sugar sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation [Internet]. 2010 Mar 23 [cited 2019 May 27];121(11):1356. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20308626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr [Internet]. 2013 Oct 1 [cited 2019 May 27];98(4):1084–102. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23966427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Luger M, Lafontan M, Bes-Rastrollo M, Winzer E, Yumuk V, Farpour-Lambert N. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review from 2013 to 2015 and a comparison with previous studies. Obes Facts [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 May 27];10(6):674–93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29237159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Bleich SN, Vercammen KA. The negative impact of sugar-sweetened beverages on children’s health: an update of the literature. BMC Obes [Internet]. 2018 Dec 20 [cited 2019 May 27];5(1):6. Available from: https://bmcobes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40608-017-0178-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Leitner DR, Frühbeck G, Yumuk V, Schindler K, Micic D, Woodward E, et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes: two diseases with a need for combined treatment strategies - EASO can lead the way. Obes Facts [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 May 27];10(5):483–92. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29020674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Barnes AS. The epidemic of obesity and diabetes: trends and treatments. Texas Hear Inst J [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 May 27];38(2):142–4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21494521 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.WHO. Action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases in the WHO European Region 2016–2025. 2016 Aug 15 [cited 2019 May 27]; Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases/pages/policy/publications/action-plan-for-the-prevention-and-control-of-noncommunicable-diseases-in-the-who-european-region-20162025

- 19.Republic Slovenia Ministry of Health . Resolution on the National Programme on Nutrition and Physical Activity for Health 2015–2025. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foodwatch. How traffic light labeling works - foodwatch - foodwatch [Internet]. Red, amber and green for understandable information. 2017 [cited 2018 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.foodwatch.org/more-information/how-traffic-light-labeling-works/

- 21.FSANZ. Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code: Schedule 5 – Nutrient profiling scoring method. In: Food standards Gazette, F2017C00318 [Internet]. Canberra, Australia: Attorney-General’s Department; 2017 [cited 2019 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2015L00475

- 22.Pivk Kupirovič U, Miklavec K, Hribar M, Kušar A, Žmitek K, Pravst I. Nutrient profiling is needed to improve the nutritional quality of the foods labelled with health-related claims. Nutrients [Internet]. 2019 Jan 29 [cited 2019 Oct 8];11(2). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30699918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Dunford EK, Ni Mhurchu C, Huang L, Vandevijvere S, Swinburn B, Pravst I, et al. A comparison of the healthiness of packaged foods and beverages from 12 countries using the Health Star Rating nutrient profiling system, 2013–2018. Obes Rev [Internet]. 2019 Jul 22 [cited 2019 Oct 8];obr.12879. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/obr.12879 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Nutrition Institute. NUTRIS - innovative solutions for informed choices [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.nutris.org/en/innovative-solutions-for-informed-choices

- 25.Zveza potrošnikov Slovenije. Semafor - živila [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug 23]. Available from: https://veskajjes.si/nasveti-in-novice/51-nasveti-za-zdravo-prehranjevanje/semafor-kaj-nam-pove

- 26.Rozman U, Pravst I, Kupirovič UP, Blaznik U, Kocbek P, Turk SŠ. Sweet, fat and salty: snacks in vending machines in health and social care institutions in Slovenia. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Sep 27 [cited 2021 Apr 6];17(19):7059. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/19/7059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.WHO. WHO Regional Office for Europe nutrient profile model [Internet]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/270716/Nutrient-children_web-new.pdf

- 28.NIJZ . Referenčne vrednosti za energijski vnos ter vnos hranil. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bray GA, Champagne CM. Beyond energy balance: there is more to obesity than kilocalories. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(5):17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bray GA, Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79:537–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Piernas C, Popkin BM. Snacking increased among U.S. adults between 1977 and 2006. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):325–332. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson AL, Buckley E, Buckley JD, Bogomolova S. Nudging healthier food and beverage choices through salience and priming. Evidence from a systematic review. Food Quality and Preference. Elsevier Ltd. 2016;51:47–64.

- 33.Young LR, Nestle M. Portion sizes and obesity: responses of fast-food companies. J Public Health Policy. 2007;28(2):238–248. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bishop K, Friedman E, Wootan M. Vending contradictions: snack and beverage options on public property [Internet]. Washington; 2014. Available from: https://cspinet.org/resource/vending-contradictions

- 35.Kibblewhite S, Bowker S, Jenkins HR. Vending machines in hospitals – are they healthy? Nutr Food Sci [Internet]. 2010 Feb 9 [cited 2019 May 28];40(1):26–8. Available from: https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/10.1108/00346651011015881

- 36.Lawrence S, Boyle M, Craypo L, Samuels S. The food and beverage vending environment in health care facilities participating in the healthy eating, active communities program. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2009 Jun [cited 2019 May 28];123(Supplement 5):S287–92. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19470605 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.U.S. Governement Publishing Office. Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act [Internet]. U.S.A.; 2004. Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/PLAW-108publ265

- 38.Committee on Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools. Nutrition standards for foods in schools: leading the way toward healthier youth: Health and Medicine Division [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2020 Jan 30]. Available from: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2007/Nutrition-Standards-for-Foods-in-Schools-Leading-the-Way-toward-Healthier-Youth.aspx

- 39.United States department of Agriculture F and NS . A guide to smart snacks in school. Alexandria. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Food and Drug Administration, HHS. Food labeling; calorie labeling of articles of food in vending machines. Final rule. Fed Regist [Internet]. 2014 Dec 1 [cited 2020 Jan 30];79(230):71259–93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25438345 [PubMed]

- 41.Victorian Government. Healthy choices: policy guidelines for hospitals and health services. Melbourne; 2016.

- 42.Government of the Republic of Slovenia . School nutrition law. 3/13, 46/14 and 46/16 – ZOFVI-L Slovenia: Official Gazette of Republic of Slovenia. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorton D, Carter J, Cvjetan B, Ni Mhurchu C. Healthier vending machines in workplaces: both possible and effective [Internet]. Vol. 123, The New Zealand medical journal. 2010 [cited 2020 Jan 30]. p. 43–52. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20360795 [PubMed]

- 44.Mason M, Zaganjor H, Bozlak CT, Lammel-Harmon C, Gomez-Feliciano L, Becker AB. Working with community partners to implement and evaluate the chicago park district’s 100% healthier snack vending initiative. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11(8):1–8. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Healthier vending machine initiatives in state facilities. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Viana J, Leonard SA, Kitay B, Ansel D, Angelis P, Slusser W. Healthier vending machines in a university setting: effective and financially sustainable. Appetite. 2018;121:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.11.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dingman DA, Schulz MR, Wyrick DL, Bibeau DL, Gupta SN. Does providing nutrition information at vending machines reduce calories per item sold? J Public Health Policy. 2015;36(1):110–122. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2014.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.French SA, Jeffery RW, Story M, Hannan P, Snyder MP. A pricing strategy to promote low-fat snack choices through vending machines. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(5):849–851. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.5.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hua SV, Kimmel L, Van Emmenes M, Taherian R, Remer G, Millman A, et al. Health promotion and healthier products increase vending purchases: a randomized factorial trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(7):1057–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stöckli S, Stämpfli AE, Messner C, Brunner TA. An (un)healthy poster: when environmental cues affect consumers’ food choices at vending machines. Appetite. 2016;96:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fiske A, Cullen KW. Effects of promotional materials on vending sales of low-fat items in teachers’ lounges. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(1):90–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoerr SM, Louden VA. Can nutrition information increase sales of healthful vended snacks? J Sch Health [Internet]. 1993 Nov [cited 2020 Jan 30];63(9):386–90. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1993.tb06167.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Kocken PL, Eeuwijk J, Van Kesteren NMC, Dusseldorp E, Buijs G, Bassa-Dafesh Z, et al. Promoting the purchase of low-calorie foods from school vending machines: a cluster-randomized controlled study. J Sch Health [Internet]. 2012 Mar [cited 2020 Jan 30];82(3):115–22. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00674.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.French SA. Pricing effects on food choices. J Nutr. 2003;133(3):841S–843S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.841S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.French SA, Jeffery RW, Story M, Breitlow KK, Baxter JS, Hannan P, Snyder MP. Pricing and promotion effects on low-fat vending snack purchases: the CHIPS study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):112–117. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Voss C, Klein S, Glanz K, Clawson M. Nutrition environment measures survey-vending: development, dissemination, and reliability. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13(4):425–430. doi: 10.1177/1524839912446321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hua SV, Ickovics JR. Vending machines: a narrative review of factors influencing items purchased. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(10):1578–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.06.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boelsen-Robinson T, Backholer K, Corben K, Blake MR, Palermo C, Peeters A. The effect of a change to healthy vending in a major Australian health service on sales of healthy and unhealthy food and beverages. Appetite. 2017;114:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carlson A, Frazão E. Cost realities of healthy foods. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2012. Are healthy foods really more expensive? It depends on how you measure the price; pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ng KW, Sangster J, Priestly J. Assessing the availability, price, nutritional value and consumer views about foods and beverages from vending machines across university campuses in regional New South Wales, Australia. Heal Promot J Aust [Internet]. 2019 Jan 28 [cited 2021 Apr 7];30(1):76–82. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/hpja.34 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.World Health Organization . Using price policies to promote healthier diets. 2015. p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Botto S, Niccolucci V, Rugani B, Nicolardi V, Bastianoni S, Gaggi C. Towards lower carbon footprint patterns of consumption: the case of drinking water in Italy. Environ Sci Policy [Internet]. 2011 Jun [cited 2019 May 27];14(4):388–95. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1462901111000141

- 63.Gleick PH, Cooley HS. Energy implications of bottled water. Environ Res Lett [Internet]. 2009 Jan 19 [cited 2018 Sep 26];4(1):014009. Available from: http://stacks.iop.org/1748-9326/4/i=1/a=014009?key=crossref.0a06e29f584eaefeb055778cbbd03e7b

- 64.Finance. Kje je voda najcenejša [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2018 Sep 26]. Available from: https://www.finance.si/238946

- 65.PlasticsEurope. The compelling facts about plastics - 2008 - PVC [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2018 Sep 26]. Available from: http://www.pvc.org/en/p/the-compelling-facts-about-plastics-2008

- 66.WHO. Dioxins and their effects on human health [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Sep 27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dioxins-and-their-effects-on-human-health

- 67.ECHA. Presence of microplastics and nanoplastics in food, with particular focus on seafood. EFSA J [Internet]. 2016 Jun [cited 2018 Sep 28];14(6). Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4501

- 68.Smith M, Love DC, Rochman CM, Neff RA. Microplastics in seafood and the implications for human health. Curr Environ Heal reports [Internet]. [cited 2019 Apr 11];5(3):375–86. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jabeen N, Majid I, Nayik GA. Bioplastics and food packaging: a review. Yildiz F, editor. Cogent Food Agric [Internet]. 2015 Dec 14 [cited 2019 Oct 9];1(1). Available from: https://www.cogentoa.com/article/10.1080/23311932.2015.1117749

- 70.Marsh K, Bugusu B. Food packaging? Roles, materials, and environmental issues. J Food Sci [Internet]. 2007 Apr 1 [cited 2019 Oct 9];72(3):R39–55. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00301.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Coles R, Derek M, Kirwan MJ, editors. Food packaging technology. UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2003. p. 349. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.