Abstract

Hypeptin is a cyclodepsipeptide antibiotic produced by Lysobacter sp. K5869, isolated from an environmental sample by the iChip technology, dedicated to the cultivation of previously uncultured microorganisms. Hypeptin shares structural features with teixobactin and exhibits potent activity against a broad spectrum of gram‐positive pathogens. Using comprehensive in vivo and in vitro analyses, we show that hypeptin blocks bacterial cell wall biosynthesis by binding to multiple undecaprenyl pyrophosphate‐containing biosynthesis intermediates, forming a stoichiometric 2:1 complex. Resistance to hypeptin did not readily develop in vitro. Analysis of the hypeptin biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) supported a model for the synthesis of the octapeptide. Within the BGC, two hydroxylases were identified and characterized, responsible for the stereoselective β‐hydroxylation of four building blocks when bound to peptidyl carrier proteins. In vitro hydroxylation assays corroborate the biosynthetic hypothesis and lead to the proposal of a refined structure for hypeptin.

Keywords: antibiotic, cell wall, cyclodepsipeptide, hydroxylase, lipid II

The nonribosomal peptide hypeptin blocks cell wall biosynthesis of gram‐positive bacteria by binding to lipid II. It kills pathogens even in late exponential growth phase without detectable development of resistance. Investigation of the biosynthesis in vitro, combined with bioinformatic and NMR analyses led to the proposal of a refined structure.

The rapid emergence and worldwide spread of infections caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria represents a serious health threat, while the identification and development of novel antibiotic classes is scarce. Particularly, the pressing need for resistance‐breaking antibiotics reinforced the focus on natural products, though increasingly becoming harder to find. Overmining of this limited resource in the 1960s ended the golden era of antibiotic discovery and, despite intensive effort, synthetic approaches were unable to replace natural products. [1]

To access a greater diversity of antibiotic producing microorganisms, novel cultivation methods have been developed. The iChip (isolation chip) technology was designed for high‐throughput in situ cultivation of previously “uncultured” bacteria.[ 2 , 3 ] The iChip device enables to simultaneously cultivate and isolate about 50 % of soil bacteria, compared with only 1 % of strains that grow under laboratory conditions. This method facilitated the discovery of teixobactin, representing an entirely novel antibiotic class, produced by the previously uncultured β‐proteobacterium Eleftheria terrae. [3] Another extract from the same screen that led to the discovery of teixobactin showed potent activity against Staphylococcus aureus. Bioassay‐guided fractionation of culture extracts, followed by MALDI‐TOF analysis, identified the bioactive compound, as a peak with a [M+H]+ ion at m/z 1022.489 (Figure S1). Comparison with natural product databases pointed towards the known compound hypeptin (1, Figure 1), previously isolated from Pseudomonas sp. PB‐6269 by Shionogi & Co. in 1989. [4] The producing strain K5869, isolated by the iChip was then cultivated in larger scale and 1 was isolated as described in the Supporting Information (SI, page 3), yielding approximately 18 mg of 1 from a 3 L culture.

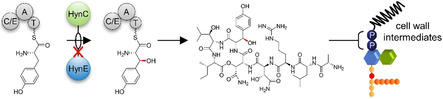

Figure 1.

Gene organization of the hyn BGC and biosynthetic pathway of hypeptin (1). The NRPS HynAB assemble a linear octapeptide which is finally released and cyclized by HynBTE. The tailoring hydroxylases HynC and HynE (green) modify the building blocks during assembly. Has: 3‐Hydroxyasparagine Hty: 3‐Hydroxytyrosine Hle: 3‐Hydroxyleucine.

NMR and other spectroscopic analyses further confirmed the identity of 1 (Figures S2–S11, Table S2), being an octadepsipeptide with a four‐residue macrocycle. A comparably high proportion of amino acids, comprising half of the peptide backbone, are β‐hydroxylated, which gave the compound the name hypeptin. [4] Determination of the absolute stereoconfiguration of 1 had revealed three amino acids to be d‐configurated and three out of four amino acids to contain R‐configuration at the β‐carbon (2S,3R)‐3‐OH‐Asn4 (Has), (2R,3R)‐3‐OH‐Asn5, (2S,3S)‐3‐OH‐Tyr6 (Hty), and (2S,3R)‐OH‐Leu7 (Hle). The configuration of Hty had not been experimentally determined due to degradation during hydrolysis, and NMR spectra were not provided in the original publication. [4]

We next sequenced the genome of the newly isolated producing strain K5869. 16S rDNA analysis revealed the organism to belong to the genus Lysobacter, γ‐proteobacteria known to produce a range of secondary metabolites including compounds with antibacterial and antifungal bioactivities. [5] The overall structure of 1 suggested a nonribosomal origin. Nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) are multimodular megaenzymes that assemble peptides in a thiotemplated manner. A minimal NRPS elongation module, known to recruit specific amino acid building blocks and extend the growing peptide chain, consists of condensation (C), adenylation (A), and thiolation (T) domains, also named peptidyl carrier proteins. [6] Some A domains are dependent on the interaction with a small MbtH‐like protein (MLP) to maintain their correct conformation and/or catalytic activity. [7] To analyze the biosynthesis of 1, the genome sequence was searched for candidate NRPS biosynthetic gene clusters (BGC). AntiSMASH [8] analysis revealed a BGC with two NRPS genes (Table S3), that we termed hynA (19.4 kb) and hynB (7.3 kb), encoding six and two modules, respectively (Figure 1). The number of modules and predicted A domain specificities, as well as C domain functions, were consistent with the overall structure of 1. Module 5 harbors a scarce additional C domain, that clusters together with known Cβ epimerases in phylogenetic analysis (Figure S12, Table S4).[ 9 , 10 ] Interestingly, the active site of the C domain contains a HRxxxDR sequence, which would render the domain inactive by the bulky side chains of the arginines. The identical Cβ configuration of Has4 and Has5 in the final peptide strongly supports this theory. BLAST analysis of the genes hynAB revealed an identical BGC in the genome of Lysobacter psychrotolerans ZS60 (NZ_RIBS01000 005.1), which helped to manually determine the borders of the BGC.

Despite extensive bioinformatic searches with BLAST and BigFAM, [11] no further related BGCs were identified in the databases. In addition to the two NRPS genes hynAB, bioinformatic analysis revealed two putative hydroxylases to be encoded in the BGC: HynC is a non‐heme diiron monooxygenase (NHDM), a barely studied enzyme family, so far only described in the biosyntheses of chloramphenicol, teicoplanin, and FR900359,[ 12 , 13 , 14 ] while HynE is annotated as an α‐ketoglutarate‐dependent oxygenase (αKG). [15] Additional genes (hynDFG) likely represent transporter‐related genes. The hyn BGC, comprising a 35.6 kb region, is located in the 5′‐end of a giant cluster with four other BGCs. The 3′‐end of this region encodes a stand‐alone MLP (hynMLP) that was assumed to be involved in the biosynthesis of 1.

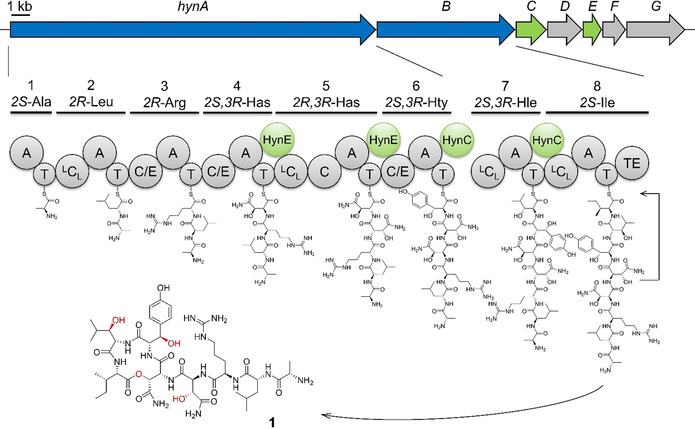

The different stereoconfiguration of the β‐hydroxyl groups in 1 raised questions about the hydroxylation reactions in hypeptin biosynthesis. We thus focused on the characterization of the two different hydroxylases HynC and HynE, for which the nature of substrates is unclear. β‐hydroxyl moieties in amino acids can be introduced by different mechanisms, either on the free amino acid or on the aminoacylated T domain during NRPS assembly. Comparable examples of NHDM and αKG were shown to hydroxylate their substrate amino acid when covalently bound to the cognate T domain.[ 14 , 15 ] Interestingly, all characterized NHDM are known to hydroxylate their substrate l‐amino acids in syn‐configuration,[ 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 ] whereas for αKG, hydroxylation of products in both configurations is reported. [16] Therefore, we hypothesized, that the αKG HynE might hydroxylate either free or T domain‐bound Asn4, Asn5 and Tyr6 prior to further modification, while the NHDM HynC would act on Leucinyl‐T7. We aimed at analyzing β‐hydroxylation reactions in vitro to determine the substrate specificity of HynC and HynE. To this end, modules 4, 5, 6, and 7 were cloned and expressed in E. coli for in vitro reconstitution. As NRPS multidomain proteins frequently show difficulties to express heterologously in a soluble and active form, [13] we cloned different constructs of each module: AT, CAT, ATC or CaccATCdon, the latter two designed after the recently introduced XU‐ and XUC‐exchange modules. [17] These were developed as exchange modules for NRPS engineering, but we also found them effective to define appropriate borders for successful in vitro reconstitution. Most of the attempted constructs yielded truncated or insoluble proteins, even when co‐expressed with chaperones. The enzymatic activity of the A domains within the constructs was verified with the γ18O4‐ATP exchange assay. [18] Finally, we obtained the soluble and functional enzymes HynA4CaccATCdon, HynA5CAT, HynA6CAT, and HynB7AT. HynA5CAT and HynA6CAT needed to be co‐expressed with HynMLP, which is located ≈300 000 bp downstream of the hyn genes, to exhibit adenylating activity towards their preferred substrates l‐Asn and l‐Tyr. HynE was efficiently expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3), whereas HynC had to be co‐expressed with each of the four different NRPS modules to be soluble and stable in vitro (Figure S13).

With all enzymes in hand, we performed hydroxylation assays for HynC and HynE, each with all four purified NRPS modules. For HynE, we could detect the mass of the hydroxylated amino acids in the assays with HynA4CaccATCdon and HynA5CAT after hydrolysis from the NRPS, but not with HynA6CAT and HynB7AT. On the other hand, the masses of Hty and Hle were detected in HynC assays with HynA6CAT and HynB7AT, respectively (Figure 2). We also detected Hle in the negative control of the assay with HynB7AT, which was probably caused by in vivo hydroxylation during co‐expression. To circumvent this, we generated the inactive mutant HynC E375D. An analogous mutation in the active site of the prototype NHDM, CmlA, was reported to lack oxygen regulation and thereby impaired hydroxylation activity, without any structural changes. [19] Indeed, when using co‐expressed HynC E375D as negative control in the hydroxylation assay, the signal of Hle diminished almost completely (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Results of in vitro assays to test NRPS and hydroxylase activities. On the left, the A domain specificity towards the substrate amino acid and the dependency of the MbtH‐like protein (MLP) HynMLP was examined for each module via γ18O4‐ATP exchange assay. On the right, extracted LC‐MS traces of the hydroxylation assays of the module construct with HynC and HynE show formation of hydroxylated amino acids in comparison with the respective negative controls. At the bottom, the formation of the hydroxylated amino acid is summarized. a) The A domain of module 4 activates l‐Asn and is independent of HynMLP. HynE then hydroxylates the bound amino acid, leading to the formation of 3‐hydroxyasparagine (Has) (m/z=147.0). b) The A domain in module 5 activates l‐Asn only in presence of HynMLP. HynE then hydroxylates the bound amino acid, leading to the formation of 3‐hydroxyasparagine (Has) (m/z=147.0). c) The A domain of module 6 activates l‐Tyr in the presence of HynMLP. Subsequently, HynC hydroxylates the amino acid (m/z=196.1). d) The A domain of module 7 activates l‐Leu independently of HynMLP. HynC then hydroxylates the amino acid (m/z=146.1).

We speculated, that the synthetase utilizes the two hydroxylases to obtain hydroxylated amino acids in different stereoconfiguration. Our in vitro hydroxylation assays unambiguously demonstrate, that HynE targets the T domain‐bound l‐Asn4 and l‐Asn5, whereas the NHDM HynC hydroxylates the T domain‐bound l‐Tyr6 and l‐Leu7. These results contradict the published configuration of Hty in 1 that was reported as (2S,3S) (anti), but, according to our in vitro data, should be (2S,3R) (syn). We were not able to verify the absolute configuration of Hty in the final peptide due to fast degradation of the amino acid during hydrolysis of 1 as observed previously. [4] Nevertheless, the observed high coupling constant between H2Hty and H3Hty of 7.2 Hz (Table S2) strongly indicates syn configuration in accordance with a published study on a Hty‐containing peptide. [20] According to the results of our γ18O4‐ATP exchange assay, the preferred substrate of the A6 domain is (2S)‐Tyr and the module does not contain any epimerase domain. In the light of these data, we propose to reassign the absolute configuration of the Hty residue in 1 to (2S,3R)‐OH‐Tyr. Analysis of ROESY correlations supports this configuration (Figure S14).

1 shows striking similarity with teixobactin, including a macrolactam ring of the same size, a comparable number of d‐ and l‐amino acids, the presence of a guanidine amino acid, and β‐hydroxy amino acids, suggesting a common mechanism of action for both compounds. [21] As observed for teixobactin, 1 exhibited potent antibacterial activity against gram‐positive pathogens (Table 1), including drug‐resistant staphylococci, such as methicillin‐resistant, vancomycin intermediate resistant and daptomycin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA, VISA and DAPR), with minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) in the ng mL−1 range. 1 further showed very good activity against mycobacteria and vancomycin‐resistant enterococci (VRE) (Table 1), but was lacking activity against gram‐negative species, most likely owing to the outer membrane permeability barrier, preventing penetration of the rather large compound. This is supported by the decreased MIC of E. coli strain MB5746 with a defective outer membrane. [22]

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of 1 against selected strains and pathogenic bacteria.

|

Organism |

MIC [μg mL−1] |

|---|---|

|

Bacillus subtilis 168 |

0.0625 |

|

S. simulans 22 |

0.125 |

|

S. aureus SG 511 |

0.0625 |

|

S. aureus SG 511 (DAPR) |

0.0625 |

|

S. aureus LT‐1334 (MRSA) |

0.25 |

|

S. aureus 137/93G (VISA) |

0.5 |

|

Enterococcus faecium I‐11054 (VRE) |

2 |

|

Mycobacterium bovis BGG |

0.25 |

|

E. coli MB5746 |

4 |

|

E. coli O‐19592 |

16 |

|

Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 |

>64 |

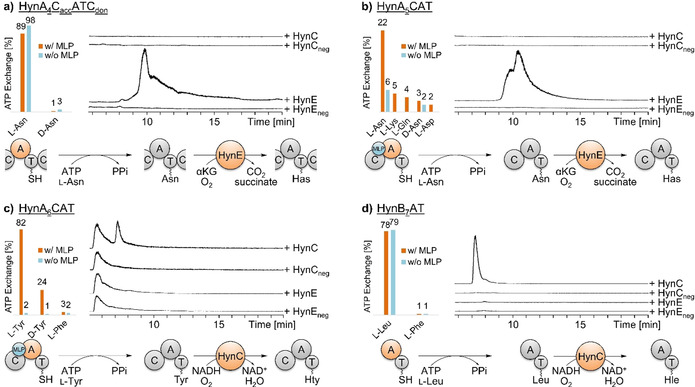

Killing kinetics of S. aureus exposed to 1 showed excellent bactericidal activity, even superior to vancomycin and teixobactin in killing late exponential phase cultures at 5‐fold lower compound concentration (Figure 3 A, B). 1 had a strong lytic effect even at a concentration corresponding to 2× MIC and showed enhanced lysis compared to vancomycin (Figure 3 C). Despite the pronounced lytic activity, 1 exhibits specificity for bacterial cells, indicating a favorable therapeutic window, as only moderate cytotoxic effects towards HEp‐2 cells and low hemolytic activity toward red blood cells (RBCs) were observed at the highest concentration tested (128 μg mL−1) (Figure S15).

Figure 3.

1 shows excellent bactericidal activity against S. aureus. Time‐dependent killing of early‐exponential (a) and late‐exponential phase‐grown (b) cells treated with 1 at 1× (open circles) and 2× MIC (circles), with teixobactin (diamonds) and vancomycin (triangles) both at 10× MIC. Cells left untreated are shown with squares. Data are representative of three independent experiments. c) 1‐induced lysis is mediated by the major autolysin AtlA in S. aureus. Deletion of atlA results in markedly reduced autolysis after treatment with 1 and TEIX.

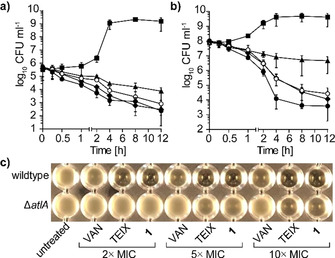

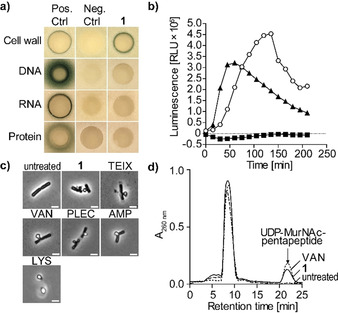

To identify the antibiotic target pathway of 1, we employed pathway‐selective gram‐positive bioreporter strains. 1 specifically induced the B. subtilis PypuA‐lacZ reporter strain indicative for interference with cell wall biosynthesis, while all other major biosyntheses (DNA, RNA, protein) remained unaffected (Figure 4 A). Substantiating inhibition of cell wall biosynthesis, treatment with 1 strongly inhibited incorporation of radiolabeled glucosamine, an essential precursor of cell wall biosynthetic reactions (Figure S16). Furthermore, treatment of B. subtilis with 1 induced severe cell‐shape deformations as visualized by phase‐contrast microscopy (Figure 4 C). The formation of membrane bulges and blebs is characteristically induced by many cell wall‐acting antibiotics and was similarly observed with teixobactin and plectasin (Figure 4 C). [23]

Figure 4.

1 targets bacterial cell wall biosynthesis. a) B. subtilis bioreporter strains with selected promotor‐lacZ gene fusions were used to identify interference with major biosynthesis pathways including cell wall (PypuA), DNA (PyorB), RNA (PyvgS), and protein (Pyhel). A blue halo at the edge of the inhibition zone demonstrates induction of a specific stress response by β‐galactosidase expression. Antibiotics vancomycin (VAN), ciprofloxacin, rifampicin, and clindamycin were used as positive controls. b) Treatment with 1 (1×MIC, open circles) strongly induced Plial as observed by expression of the lux operon from Photorhabdus luminescens in B. subtilis PliaI‐lux. VAN (triangles) and clindamycin (CLI, squares) were used as control antibiotics. c) Phase‐contrast microscopy of B. subtilis confirmed impairment of cell wall integrity as severe cell‐shape deformations and characteristic blebbing were observed following 1 treatment. Cell wall active antibiotics teixobactin (TEIX), VAN, plectasin (PLEC), ampicillin (AMP), and lysozyme (LYS) were used as controls. Scale bar=2 μm. d) Intracellular accumulation of the cell wall precursor UDP‐MurNAc‐pentapeptide after treatment of S. aureus with 1 (5×MIC). Untreated and VAN‐treated (5×MIC) cells were used as controls. Experiments are representative of 3 independent experiments each.

Despite the membrane alterations observed, 1 did not trigger pore formation or membrane disintegration. In contrast to the lantibiotic nisin, no rapid pore formation was observed (Figure S17 A). Furthermore, the membrane potential of 1‐treated S. simulans 22 cells remained unaffected even at higher concentrations (5× MIC) (Figure S17 B), as quantified by intra‐ and extracellular concentrations of the tritium‐labeled lipophilic cation TPP+. In line with these observations, 1 did not impact the cellular localization of the cell division inhibitor MinD of B. subtilis. MinD is bound to the membrane via a C‐terminal amphipathic helix and requires the presence of the membrane potential for its specific cellular localization pattern. In growing cells, MinD accumulates at the newly formed cell poles to direct FtsZ to mid‐cell division site and specific FtsZ positioning to guide division septum placement.[ 17 , 24 ] While treatment with CCCP resulted in a rapid delocalization and irregular dispersion of GFP‐MinD within 2 min, localization of the fusion protein was unchanged in 1‐treated cells and only slightly affected with prolonged incubation time (30 min) (Figure S17 C).

In search of the molecular target within the peptidoglycan (PGN) biosynthesis pathway, we investigated the effect of 1 on the LiaRS stress response in B. subtilis. LiaRS is a two‐component system (TCS), which is known to respond to antibiotics that interfere with the lipid II biosynthesis cycle. [25] Monitoring bioluminescence of reporter cells treated with 1 over time revealed a strong induction of PliaI ‐lux, even exceeding induction levels observed with the lipid II‐binding antibiotic vancomycin, indicating interference of 1 with the lipid II biosynthesis cycle (Figure 4 B). Mechanism of action studies revealed that the structurally‐related teixobactin impairs cell wall biosynthesis by blocking several cell envelope precursors containing an undecaprenyl‐pyrophosphate linkage unit including the ultimate PGN building block lipid II. [26]

PGN biosynthesis takes place in three different cellular compartments of a bacterial cell. Synthesis starts in the cytoplasm with the formation of the ultimate soluble precursor uridine diphosphate‐N‐acetylmuramic acid‐pentapeptide (UDP‐MurNAc‐pentapeptide), which is then transferred to the membrane‐anchor undecaprenyl phosphate (C55P) to yield lipid I (undecaprenyl‐pyrophosphoryl‐MurNAc‐pentapeptide). Subsequently, the addition of N‐acetylglucosamine (UDP‐GlcNAc) yields lipid II (undecaprenyl‐pyrophosphoryl‐MurNAc‐pentapeptide‐GlcNAc), which can further be species‐specifically modified. Modified lipid II is translocated to the outer surface of the membrane and incorporated into the PGN polymer (Figure S18).

Antibiotics that interfere with late stages of PGN synthesis, such as vancomycin, trigger the accumulation of UDP‐MurNAc‐pentapeptide in the cytoplasm. To distinguish whether 1 interferes with the early cytoplasmic or the late membrane‐associated steps of PGN synthesis, we determined the cytoplasmic levels of UDP‐MurNAc‐pentapeptide of S. aureus cells treated with 1. Treatment with 1 led to the intracellular accumulation of UDP‐MurNAc‐pentapeptide similar to the vancomycin control (Figure 4 D), suggesting that one of the later membrane‐associated or extracellular biosynthesis steps is targeted. Taken together, results from whole cell experiments strongly supported the hypothesis that 1 and teixobactin, in accordance with their structural resemblance, share the same mechanism of action.

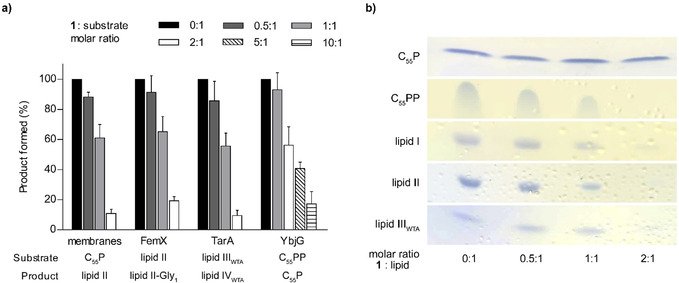

Based on this, we analyzed the impact of 1 on the membrane‐associated steps of PGN biosynthesis in vitro to identify the molecular target of 1. The first membrane‐linked step of PGN synthesis is catalyzed by MraY, which transfers UDP‐MurNAc‐pentapeptide to the lipid carrier C55P yielding lipid I. [27] Subsequently, the glycosyltransferase MurG adds UDP‐activated GlcNAc to the muramyl moiety of lipid I, yielding lipid II. [28] Membrane preparations of M. luteus possess the enzymatic activity of MraY and MurG to synthesize lipid II from the substrates UDP‐MurNAc‐pentapeptide, [14C]‐UDP‐GlcNAc and C55P. [29] Testing the reactions in the presence of increasing concentrations of 1 resulted in a dose‐dependent inhibition of overall lipid II synthesis. Full inhibition was observed at a twofold molar excess of 1 with regard to the substrate C55P (Figure 5 A). In staphylococci, lipid II is modified by the addition of five glycine residues, catalyzed by FemXAB peptidyltransferases. [30] Testing the impact of 1 on the FemX‐catalyzed addition of a glycine residue to lipid II revealed, that the reaction was fully blocked at a 2:1 stoichiometry (antibiotic:lipid II), indicating the formation of a complex with the substrate rather than inhibition of the enzyme (Figure 5 A), as observed for teixobactin. [3] In addition, 1 inhibited the YbjG‐catalyzed dephosphorylation of C55PP to C55P, although higher concentrations (10:1) were required for complete inhibition. This indicates that the pyrophosphate moiety is crucial for antibiotic interaction, but the first sugar attached to the lipid carrier contributes to high binding affinity. However, the nature of the sugar appears less important, as 1 further efficiently inhibited the synthesis of the wall teichoic acid (WTA) precursor lipid IVWTA (undecaprenyl‐pyrophosphoryl‐GlcNAc‐ManNAc) (Figure 5 A, Figure S18).

Figure 5.

1 binds to undecaprenyl pyrophosphate‐containing cell wall precursors. a) 1 interferes with membrane‐associated steps of PGN and WTA synthesis in vitro. The antibiotic was added in molar ratios from 0.5 to 10 with respect to the amount of the lipid substrate C55P, C55PP, lipid II, or lipid IIIWTA used in the individual test system. The amount of reaction product synthesized in the absence of 1 was taken as 100 %. Mean values from three independent experiments are shown. Error bars represent standard deviation. b) 1 forms extraction‐stable complexes with C55PP‐containing purified cell wall precursors including the PGN precursors lipid I and lipid II, the WTA intermediate lipid IIIWTA and C55PP. Cell wall intermediates are fully locked in a complex at a twofold molar excess of 1. No complex formation was observed with C55P. Binding of 1 is indicated by a reduction of the amount of free lipid intermediates visible on the TLC. The chromatograms are representative of two independent experiments.

Consistently, 1 efficiently trapped lipid intermediates containing a C55PP moiety in a stable complex that prevented extraction of the lipid intermediate from the reaction mixture when added in a twofold molar excess, indicating to the formation of a 2:1 stoichiometric complex. Complex formation was not observed with C55P, confirming the lipid pyrophosphate moiety to be the minimal binding motif (Figure 5 B). The inability of 1 to bind to C55P further shows that inhibition of the in vitro lipid II synthesis using membrane preparations (Figure 5 A), relies on binding to the reaction products, lipid I and lipid II, rather than the C55P substrate.

To validate that the antimicrobial activity of 1 relies on complex formation with cell wall lipid intermediates, antagonization assays with selected purified precursors were performed. In line with the in vitro analyses, the addition of C55PP‐containing lipid intermediates counteracted 1 from inhibiting growth of S. aureus similar to teixobactin (Table S5). However, compared to lipid I and lipid II, the addition of lipid IIIWTA or C55PP was less effective, since 4‐fold higher concentrations were required to fully antagonize the antimicrobial activity of 1, pointing to differences in the binding modes, that may involve interactions with the first sugar in lipid II. As expected, C55P and the anionic phospholipid 1,2‐dioleoyl‐sn‐glycero‐3‐phosphoglycerol (DOPG) had no antagonistic effect.

Binding of 1 to lipid II blocks PGN biosynthesis resulting in a defective cell wall ultimately leading to cell death. In contrast to PGN, WTAs are not essential per se, but blocking WTA biosynthesis can result in the lethal accumulation of toxic intermediates and indirectly effect PGN biosynthesis, as the molecular machineries of both pathways are tightly interlinked. [31] In addition, WTAs anchor autolysins and thereby prevent uncontrolled hydrolysis of PGN, [32] suggesting that inhibition of WTA biosynthesis by binding WTA lipid intermediates helps to liberate autolysins. In agreement, 1‐induced lysis was markedly reduced in a ΔatlA mutant, compared to wildtype S. aureus cells (Figure 3 C), confirming that lysis induced by 1 is dependent on the major autolysin AtlA in S. aureus. Our results further show that co‐targeting of lipid II and WTA lipid intermediates by 1 cause synergistic effects by weakening the PGN structure and liberation of autolysins, which synergistically lead to cell lysis and death. In addition, multiple‐targeting strongly reduced the propensity to develop resistance, as we could not generate resistant mutants of S. aureus by serial passaging on incrementing concentrations of 1.

Novel antibiotics with resistance breaking mechanisms of action are urgently needed to counteract the continuing spread of drug resistant pathogens. Hypeptin (1) is a cyclodepsipeptide that shares structural similarity with teixobactin (Figure S19).

1 contains four β‐hydroxylated amino acids with different stereoconfiguration. We investigated the substrate specificity and stereoselectivity of the two tailoring hydroxylases HynC and HynE in vitro, which revealed specific interactions of both hydroxylases with their cognate domains. A transient hydrophobic interaction with a cognate T domain was characterized for the skyllamycin CYP450 β‐hydroxylase, but the reason for specific recognition could not be determined. [33] Understanding and predicting domain interaction specificity of NRPS tailoring enzymes is a hallmark for future engineering attempts, a feature we are currently investigating. The structure revision of 1 based on bioinformatics, biochemical assays and extensive NMR analyses highlights the value of integrating these approaches for complex natural product structure elucidation.

Elucidation of the mechanism of action revealed, that 1 inhibits cell wall biosynthesis by binding to C55PP‐containing lipid intermediates within PGN, WTA, and capsule biosynthesis. Binding to multiple of these non‐protein target structures within different biosynthesis pathways explains the potent activity towards a broad range of gram‐positive pathogens, including drug resistant and difficult to treat strains, suggesting that the concomitant targeting of these precursors confers “intrinsic synergy”. Besides the mere blocking of cell wall biosynthesis, binding to WTA precursors further triggered deregulation of autolysis resulting in rapid and uncontrolled lysis and impressive bactericidal activity.

The exact knowledge of the mode of action and molecular target, together with a deeper understanding of the structure–activity relationships (SAR) will support rational design of synthetic analogs of 1. Synthetically generated teixobactin variants with modified N‐terminus, by either replacing the linear chain by a lipophilic moiety [34] or the attachment of hydrophobic residues to N‐Me‐d‐Phe1, [35] have been reported to exhibit potent anti‐microbial activity. Likewise, the semisynthetic attachment of hydrophobic moieties to the N‐terminal d‐Ala1 may increase membrane interaction and target binding of 1. Notably, 1 was most refractory to resistance development in vitro, suggesting that the combined cellular activities, triggered by targeting different cell wall precursors, account for the reduced propensity to develop resistance, making this antibiotic class a favorable scaffold for development.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—Project‐ID 398967434—TRR 261, the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) (TTU Novel Antibiotics) and the InfectControl2020 initiative (BMBF project TFP‐TV10). M.C. acknowledges the DFG (grant No. CR464/7‐1) for funding. Funding was provided by NIH grant AI091224 to ALS. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

D. A. Wirtz, K. C. Ludwig, M. Arts, C. E. Marx, S. Krannich, P. Barac, S. Kehraus, M. Josten, B. Henrichfreise, A. Müller, G. M. König, A. J. Peoples, A. Nitti, A. L. Spoering, L. L. Ling, K. Lewis, M. Crüsemann, T. Schneider, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 13579.

Contributor Information

Dr. Max Crüsemann, Email: mcruesem@uni-bonn.de.

Prof. Tanja Schneider, Email: tschneider@uni-bonn.de.

References

- 1. Lewis K., Nature 2012, 485, 439–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nichols D., Cahoon N., Trakhtenberg E. M., Pham L., Mehta A., Belanger A., Kanigan T., Lewis K., Epstein S. S., Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 2445–2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ling L. L., Schneider T., Peoples A. J., Spoering A. L., Engels I., Conlon B. P., Mueller A., Schäberle T. F., Hughes D. E., Epstein S., et al., Nature 2015, 517, 455–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shoji J., Hinoo H., Hattori T., Hirooka K., Kimura Y., Yoshida T., J. Antibiot. 1989, 42, 1460–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xie Y., Wright S., Shen Y., Du L., Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012, 29, 1277–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Süssmuth R. D., Mainz A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3770–3821; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 3824–3878. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller B. R., Drake E. J., Shi C., Aldrich C. C., Gulick A. M., J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 22559–22571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blin K., Shaw S., Steinke K., Villebro R., Ziemert N., Lee S. Y., Medema M. H., Weber T., Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W81–W87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Graupner K., Scherlach K., Bretschneider T., Lackner G., Roth M., Gross H., Hertweck C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 13173–13177; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 13350–13354. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hou J., Robbel L., Marahiel M. A., Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 655–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kautsar S. A., Blin K., Shaw S., Weber T., Medema M. H., Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D490–D497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hermes C., Richarz R., Wirtz D. A., Patt J., Hanke W., Kehraus S., Voß J. H., Küppers J., Ohbayashi T., Namasivayam V., et al., Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaniusaite M., Goode R. J. A., Schittenhelm R. B., Makris T. M., Cryle M. J., ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 14, 2932–2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Makris T. M., Chakrabarti M., Münck E., Lipscomb J. D., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 15391–15396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Singh G. M., Fortin P. D., Koglin A., Walsh C. T., Biochemistry 2008, 47, 11310–11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Reitz Z. L., Hardy C. D., Suk J., Bouvet J., Butler A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 19805–19814; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Strieker M., Nolan E. M., Walsh C. T., Marahiel M. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 13523–13530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bozhüyük K. A. J., Fleischhacker F., Linck A., Wesche F., Tietze A., Niesert C.-P., Bode H. B., Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Phelan V. V., Du Y., McLean J. A., Bachmann B. O., Chem. Biol. 2009, 16, 473–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jasniewski A. J., Knoot C. J., Lipscomb J. D., Que L., Biochemistry 2016, 55, 5818–5831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin Z., Falkinham J. O., Tawfik K. A., Jeffs P., Bray B., Dubay G., Cox J. E., Schmidt E. W., J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 1518–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. von Nussbaum F., Süssmuth R. D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 6684–6686; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 6784–6786. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kodali S., Galgoci A., Young K., Painter R., Silver L. L., Herath K. B., Singh S. B., Cully D., Barrett J. F., Schmatz D., et al., J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 1669–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schneider T., Kruse T., Wimmer R., Wiedemann I., Sass V., Pag U., Jansen A., Nielsen A. K., Mygind P. H., Raventós D. S., et al., Science 2010, 328, 1168–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Strahl H., Hamoen L. W., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12281–12286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.

- 25a. Radeck J., Gebhard S., Orchard P. S., Kirchner M., Bauer S., Mascher T., Fritz G., Mol. Microbiol. 2016, 100, 607–620; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25b. Mascher T., Zimmer S. L., Smith T.-A., Helmann J. D., Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 2888–2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Müller A., Klöckner A., Schneider T., Nat. Prod. Rep. 2017, 34, 909–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ikeda M., Wachi M., Jung H. K., Ishino F., Matsuhashi M., J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 1021–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ha S., Gross B., Walker S., Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord. 2001, 1, 201–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Heijenoort Y., Derrien M., van Heijenoort J., FEBS Lett. 1978, 89, 141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.

- 30a. Schneider T., Senn M. M., Berger-Bächi B., Tossi A., Sahl H.-G., Wiedemann I., Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 675–685; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30b. Monteiro J. M., Covas G., Rausch D., Filipe S. R., Schneider T., Sahl H.-G., Pinho M. G., Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roemer T., Schneider T., Pinho M. G., Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 538–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Biswas R., Martinez R. E., Göhring N., Schlag M., Josten M., Xia G., Hegler F., Gekeler C., Gleske A.-K., Götz F., et al., PLoS One 2012, 7, e41415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Haslinger K., Brieke C., Uhlmann S., Sieverling L., Süssmuth R. D., Cryle M. J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 8518–8522; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 8658–8662. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang H., Chen K. H., Nowick J. S., ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 1823–1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zong Y., Fang F., Meyer K. J., Wang L., Ni Z., Gao H., Lewis K., Zhang J., Rao Y., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary