Abstract

Background

Cradle cap is a benign and self‐limiting variant of seborrheic dermatitis (SD) that can be distressing for parents.

Aims

To assess by clinical/laboratory/instrumental evaluation the efficacy/tolerability of a gel cream containing piroctone olamine (antifungal), biosaccharide gum‐2 (antifungal), stearyl glycyrrhetinate (anti‐inflammatory), and zinc l‐pyrrolidone carboxylate (zinc‐PCA) (antiseborrheic) in the treatment of mild/ moderate cradle cap.

Methods

In this prospective, open‐label trial, 10 infants, with mild/moderate cradle cap enrolled at the Dermatology University Clinic of Catania (Italy) used the tested gel cream twice daily for 30 days. Degree of erythema was evaluated clinically by a 5‐point severity scale (from 0=no erythema to 4=severe erythema), at baseline, at 15 and 30 days. Desquamation was rated by dermoscopy evaluation using a 5‐point scale (from 0=no desquamation to 4=severe/many large adherent white flakes), at all time points. An Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) using a 6‐point scale (from −1=worsening to 4=complete response/clear) was also performed at 30 days. Five subjects, randomly selected, underwent double microbiological evaluation for bacteria and yeasts by cultures of cotton swabs at baseline and at 30 days. Tolerability/acceptability was evaluated on a 4‐point scale (from 0=very poor to 3=excellent) at 15 and 30 days. Data were processed using SAS version 9.

Results

At baseline, a significant colony‐forming unit (CFU) count for Malassezia furfur and Staphylococcus aureus was detected in 4 out of 5 selected patients. After 15 and 30 days, a statically significant reduction from baseline in erythema and desquamation severity was observed, along with a reduction in CFU count for Malassezia furfur and Staphylococcus aureus from baseline. No signs of local side effects were documented.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that the tested gel cream may represent a valid option to treat mild‐to‐moderate forms of cradle cap and support its antifungal and antibacterial properties.

Keywords: cradle cap, dermoscopy, microbiota, topical cosmetic

1. INTRODUCTION

Cradle cap, also known as pityriasis capitis, is a variant of seborrheic dermatitis (SD) clinically characterized by yellowish, crusty, greasy patches of scaling on the scalp of infants, with or without different degrees of inflammation. 1 , 2 It generally occurs during the first month of life, showing a peak of incidence before the first year of age, and then decreases until it is negligible after 3 years. 2 , 3 Its pathogenesis is multifactorial and still poorly delineated. The age of occurrence suggests a role of excessive sebaceous gland activity from maternal and endogenous hormones. 1 A key role of skin proliferation of yeasts belonging to the Malassezia spp. (formerly called Pityrosporum ovale) is strongly supported by some evidences, although its real relevance is still unclear. 4 Several findings highlighted the presence of cutaneous microbial alterations in cradle cap, most notably including genera Staphylococcus spp, Streptococcus spp, and Corynebacterium spp. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 In particular, these commensal bacteria, although not directly responsible for infant SD, contribute to increase the “nutrients” that promote the growth of Malassezia species by hydroxylation of the sebum components. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Cradle cap is benign and self‐limiting, but it can be distressing for parents. The mainstay treatments to cure mild‐to‐moderate localized forms include baby shampoos enriched with emollient agents (ie, vegetable oil, lactic acid) followed by gentle mechanical removal of loosen scales. 2 Until now, scant scientific evidences support the effectiveness and safety of a pharmacological approach based on the use of topical antifungals (ciclopirox 1% shampoo, ketoconazole 1% cream/shampoo) or anti‐inflammatory agents (hydrocortisone 1% cream/lotion) in more severe forms of cradle cap, due to limited data. 9 , 10 Keratolytic shampoos, including those with salicylic acid, sulfur, selenium, or zinc pyrithione, are generally not recommended for the possibility of systemic absorption in newborns. 3 Similarly to adult scalp SD, 11 non‐steroidal and anti‐inflammatory with antifungal properties (AIAFp) shampoo may represent a viable option in cradle cap, as confirmed by a randomized, double‐blind clinical trial. 12

The aim of this open‐label prospective clinical trial was to assess by clinical, laboratory, and instrumental evaluation the efficacy and tolerability of a new antifungal, anti‐inflammatory, and antiseborrheic gel cream in the treatment of mild‐to‐moderate cradle cap.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

From October 2019 to October 2020, twenty infants aged from 2 months to 12 months, of both genders, affected by mild‐to‐moderate cradle cap, were enrolled at the Dermatology University Clinic of Catania (Italy). Study duration was up to 30 days. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles from the Declaration of Helsinki 1996 and in the spirit of Good Clinical Practices. A parent's written consent was obtained before the treatment was begun. Inclusion criteria were as follows: infants, of either gender, with mild‐to‐moderate cradle cap, who underwent a washout period for any topical SD treatments of at least 2 weeks. No other topical products or drugs were allowed, except for mild cleansers (fragrances and allergy‐free).

2.1. Methodology

The parents were instructed to apply the gel cream containing piroctone olamine, biosaccharide gum‐2, stearyl glycyrrhetinate, and zinc l‐pyrrolidone carboxylate (zinc‐PCA), twice daily (at morning and at bedtime) for 30 days. In order to reduce potential evaluator bias, all subjects were assessed by an investigator not directly involved in the study at baseline (T0), day 15 (T1), and 30 days (T2).

2.2. Clinical, laboratory, and instrumental criteria

Clinical evaluation of efficacy was assessed by measuring the degree of erythema by a 5‐point severity scale (0=no erythema; 1=very mild erythema/slight pink; 2=mild erythema/definite pink in a small area; 3=moderate/definite redness in a larger area; 4=severe/severe red extends to other area) at all time points and by Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) using a 6‐point scale (−1=worsening; 0=no response; 1=mild response; 2=moderate; 3=excellent; and 4=clearing) at the end of the study.

Five subjects, randomly selected, underwent double microbiological evaluation for bacteria and yeasts by cultures of cotton swabs scraped from affected as well as from healthy scalp area at baseline and at 30 days.

Desquamation was rated by polarized dermoscopy (Illuco IDS‐1100®, Tre T Medical, Camposano, Italy) at ×10 magnification using a 5‐point scale (0=no desquamation; 1=very mild: very few small loose white flakes; 2=mild: few small loose white flakes; 3=moderate: several small loose white flakes; and 4=severe: many large adherent white flakes), at all time points.

Additionally, product tolerability and acceptability were evaluated on a 4‐point scale: (0=very poor; 1= poor; 2=good; 3=excellent) at 15 and 30 days.

2.3. Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was efficacy evaluation at day 30 of all clinical parameters (erythema, desquamation) including global assessment; the secondary endpoint was tolerability evaluation and cosmetic acceptability of the product at day 30.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The quantitative data are reported as mean±standard deviation (SD), while the qualitative ones are expressed in number and percentage. The statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Data were processed using SAS version 9.

3. RESULTS

All enrolled cases (14/M,6/F; mean age: 4.7±4.2 months; range age: 2–12 months) completed the study. At baseline, a positive colony‐forming unit (CFU) count for Malassezia furfur and Staphylococcus aureus was detected in 4 out of 5 selected patients in the affected areas. In the same patients, swabs from non‐affected areas were microbiologically negative.

After 15 days, a significant reduction from baseline in erythema severity (mean from 2.1 ± 0.9 to 1.5 ± 0.5 at 15 days; p < 0.01) along with desquamation (mean from 3.1±0.2 to 1.8±0.5; p<0.01) was observed.

At 30 days, all evaluated parameters showed a progressive significant reduction from baseline (erythema severity: mean from 2.1±0.9 at baseline to 0.4±1.2 at 30 days: p < 0.0001; desquamation severity: mean from 3.1±0.2 at baseline to 0.7±0.4; p < 0.0001) (Figures 1, 2). IGA showed a complete response in 13 cases (65%), excellent in 4 (20%), and moderate in 3 (15%). No patients showed clinical worsening or no response from baseline. In addition, negative CFU count for M. furfur and Staphylococcus aureus was recorded in the 4 previously positive patients. At 1 month follow‐up, no recurrence was recorded in all patients showing complete response.

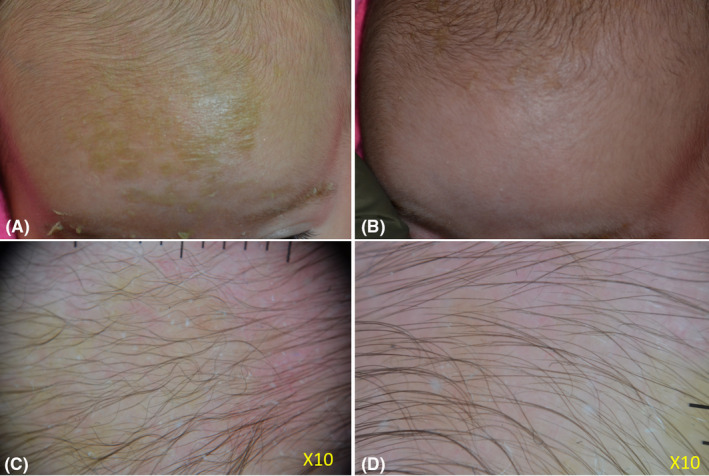

FIGURE 1.

A 2‐month‐year old girl presented with moderate cradle cap, characterized by yellowish adherent scales involving most of the scalp and the eyebrows (A). Dermoscopy evaluation (X10) of the affected area showed moderate erythema and scaling (C). The mother had been empirically applying olive oil as emollient with no improvement. Microbiological evaluation prior to treatment showed the presence of abundant Staphyloccus aureus and Malassezia spp colonies. After 30 days of treatment with the tested gel cream, used twice daily, clinical examination showed an excellent clinical response (B). The clinical result was confirmed by dermoscopy (D). Skin swabs at the end of treatment revealed normal skin flora

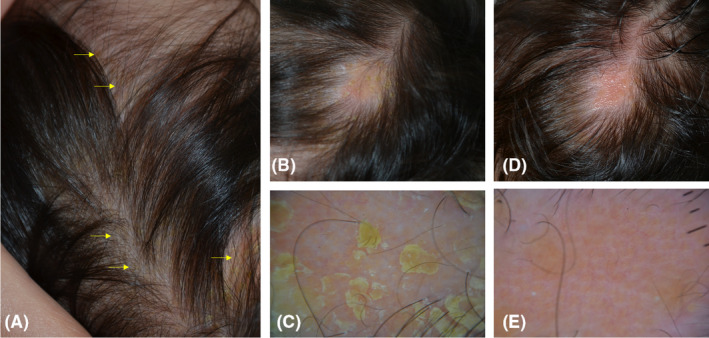

FIGURE 2.

An 11‐month‐year‐old girl presented with a cradle cap since 2 months. The topical use of emollients had been ineffective. Skin swabs were positive for Staphyloccus aureus and Malassezia spp. At clinical examination, several patches covered by yellowish, adherent scales were observed throughout the scalp (A‐B). Dermoscopy (X10) of the area showed in panel B highlighted more in detail the yellowish scales (C). After 30 days of treatment with the tested gel cream used twice daily, the cradle cap cleared at clinical (D) and dermoscopic (E) examination. Of note, dermoscopy at the end of treatment showed the presence of a previously undetected, underlying nevus sebaceous characterized by yellow dots not associated with the hair follicles. Microbiological cultures performed at the end of treatment were negative

Overall, no signs of local side effects were documented during the study and cosmetic tolerability and acceptability were rated as excellent by all patient's parents.

4. DISCUSSION

The results of this open‐label, prospective trial with clinical, laboratory and instrumental evaluation indicate that the tested antifungal, anti‐inflammatory, and antiseborrheic gel cream containing piroctone olamine, biosaccharide gum‐2, stearyl glycyrrhetinate, and zinc‐PCA is effective in mild‐to‐moderate cradle cap. The mechanisms of action of this product may be related to multiple synergist mechanisms of action of its ingredients. In particular, piroctone olamine is an antifungal effective against Malassezia spp. by chelation of iron and other mineral. 9 Biosaccharide gum‐2, has demonstrated antifungal properties (patent pending WO2019020822) as well anti‐inflammatory and soothing properties. 13 Stearyl glycyrrhetinate is a salt and ester of glycyrrhetinic acid able to exhibit anti‐inflammatory, soothing, and antipruritic effects. 14 Finally, zinc‐PCA is a inorganic well‐note compound that combines anti‐inflammatory, antimicrobial properties with antiseborrheic efficacy. 15 Of note, our microbiological results, although related to a limited number of patients, support the antifungal and antibacterial properties of the product as reported by other authors. 16 , 17

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our results indicate that the tested gel cream may represent a valid option to treat mild‐to‐moderate forms of cradle cap, being effective, well‐tolerated, and free of significant side effects. The main limitation of this study includes the relatively small case series with no placebo control group, and further studies on larger series of patients are necessary to confirm our finding and results.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None to declare.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

This study received approval by the local ethical committee.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All writers and contributors who participated in the preparation of the manuscript are listed as authors.

The manuscript is an original unpublished work, and it is not submitted for publication elsewhere.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nobles T, Harberger S, Krishnamurthy K. Cradle Cap. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Jan. PMID: 30285358. [PubMed]

- 2. Micali G, Veraldi S, Kwong CW, Suh DH, (Eds). Seborrheic Dermatitis. Macmillan Medical Communication, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheong WK, Yeung CK, Torsekar RG, et al. Treatment of seborrhoeic dermatitis in Asia: a consensus guide. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;1(4):187‐196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hay RJ. Malassezia, dandruff and seborrhoeic dermatitis: an overview. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(suppl 2):2‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen P, He G, Qian J, Zhan Y, Xiao R. Potential role of the skin microbiota in Inflammatory skin diseases. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(2):400‐409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adalsteinsson JA, Kaushik S, Muzumdar S, Guttman‐Yassky E, Ungar J. An update on the microbiology, immunology and genetics of seborrheic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29(5):481‐489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schoch JJ, Monir RL, Satcher KG, Harris J, Triplett E, Neu J. The infantile cutaneous microbiome: a review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(5):574‐580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tanaka A, Cho O, Saito C, Saito M, Tsuboi R, Sugita T. Comprehensive pyrosequencing analysis of the bacterial microbiota of the skin of patients with seborrheic dermatitis. Microbiol Immunol. 2016;60:521‐526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okokon E, Verbeek J, Ruotsalainen J, Ojo O, Bakhoya V. Topical antifungals for seborrhoeic dermatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD008138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Victoire A, Magin P, Coughlan J, van Driel ML. Interventions for infantile seborrhoeic dermatitis (including cradle cap). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD011380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dall'Oglio F, Lacarrubba F, Verzì AE, Micali G. Noncorticosteroid combination shampoo versus 1% ketoconazole shampoo for the management of mild‐to‐moderate seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp: results from a randomized, investigator‐single‐blind trial using clinical and trichoscopic evaluation. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;1(3):126‐130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. David E, Tanuos H, Sullivan T, Yan A, Kircik LH. A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled pilot study to estimate the efficacy and tolerability of a nonsteroidal cream for the treatment of cradle cap (seborrheic dermatitis). J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(4):448‐452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marseglia A, Licari A, Agostini F, et al. Local rhamnosoft, ceramides and L‐isoleucine in atopic eczema: a randomized, placebo controlled trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;25(3):271‐275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Asl MN, Hosseinzadeh H. Review of pharmacological effects of Glycyrrhiza sp. and its bioactive compounds. Phytother Res. 2008;22(6):709‐724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takino Y, Okura F, Kitazawa M, Iwasaki K, Tagami H. Zinc l‐pyrrolidone carboxylate inhibits the UVA‐induced production of matrix metalloproteinase‐1 by in vitro cultured skin fibroblasts, whereas it enhances their collagen synthesis. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2012;34(1):23‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Balato A, Caiazzo G, Di Caprio R, Scala E, Fabbrocini G, Granger C. Exploring anti‐fungal, anti‐microbial and anti‐inflammatory properties of a topical non‐steroidal barrier cream in face and chest seborrheic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(1):87‐98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Granger C, Balato A, Goñi‐de‐Cerio F, Garre A, Narda M. Novel non‐steroidal facial cream demonstrates antifungal and anti‐inflammatory properties in ex vivo model for seborrheic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019;9(3):571‐578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]