Abstract

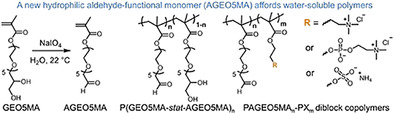

Aldehyde groups enable facile conjugation to proteins, enzymes, oligonucleotides or fluorescent dyes, yet there are no literature examples of water‐soluble aldehyde‐functional vinyl monomers. We report the synthesis of a new hydrophilic cis‐diol‐based methacrylic monomer (GEO5MA) by transesterification of isopropylideneglycerol penta(ethylene glycol) using methyl methacrylate followed by acetone deprotection via acid hydrolysis. The corresponding water‐soluble aldehyde monomer, AGEO5MA, is prepared by aqueous periodate oxidation of GEO5MA at 22 °C. RAFT polymerization of GEO5MA yields the water‐soluble homopolymer, PGEO5MA. Aqueous periodate oxidation of the terminal cis‐diol units on PGEO5MA at 22 °C affords a water‐soluble aldehyde‐functional homopolymer (PAGEO5MA). Moreover, a library of hydrophilic statistical copolymers bearing cis‐diol and aldehyde groups was prepared using sub‐stoichiometric periodate/cis‐diol molar ratios. The aldehyde groups on PAGEO5MA homopolymer were reacted in turn with three amino acids to demonstrate synthetic utility.

Keywords: aldehyde-functional methacrylic monomers, block copolymers, periodate oxidation, RAFT polymerization

A water‐soluble aldehyde monomer (AGEO5MA) was prepared by oxidation of GEO5MA at 22 °C. RAFT aqueous polymerization yielded PAGEO5MA homopolymer, which was oxidized using sub‐stoichiometric periodate/cis‐diol molar ratios to yield hydrophilic statistical copolymers with cis‐diol and aldehyde groups. Three PGEO5MA‐based diblock copolymers were converted into aldehyde‐functional copolymers, which were derivatized with amino acids.

Introduction

Aldehydes are extremely useful functional groups in synthetic organic chemistry: they can be oxidized to give carboxylic acids, reduced to afford alcohols, undergo Schiff base chemistry and also form (hemi)acetals. [1] In the field of synthetic polymer chemistry, aldehyde‐based initiators[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ] have been utilized to prepare various types of aldehyde‐functional polymers. Alternatively, Bilgic and Klok derivatized poly(2‐hydroxyethyl methacrylate) brushes under oxidative conditions in order to introduce aldehyde groups for subsequent oligonucleotide conjugation. [9] However, surprisingly few aldehyde‐functional monomers have been reported in the literature.[ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ] Most of these examples are hydrophobic (e.g. 4‐vinylbenzaldehyde) and hence produce water‐insoluble polymers.[ 16 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ] This is unfortunate, because aldehyde groups enable facile conjugation to peptides/proteins and water‐soluble dyes in aqueous solution under mild conditions.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 10 , 25 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ] In principle, this problem can be circumvented by statistical copolymerization of the hydrophobic aldehyde‐functional monomer with a sufficiently hydrophilic comonomer.[ 12 , 13 , 15 , 25 , 33 , 39 ] Alternatively, the incorporation of a terminal protected aldehyde moiety onto a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) chain has been utilized to confer aldehyde functionality under aqueous conditions.[ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 40 , 41 ] Nevertheless, despite the remarkable progress made in synthetic polymer chemistry over the past few decades, there seem to be few, if any, literature examples of hydrophilic aldehyde‐functional vinyl monomers and their corresponding water‐soluble homopolymers.

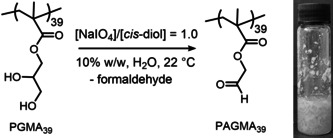

One well‐known route to aldehyde‐terminated water‐soluble polymers is the selective oxidation of the minor fraction of cis‐diol units within poly(vinyl alcohol). [42] This water‐soluble polymer can be obtained via hydrolysis of poly(vinyl acetate), which contains such cis‐diols as defect sites resulting from a small amount of head‐to‐head coupling during the free radical homopolymerization of vinyl acetate. [43] Oxidation is readily achieved in aqueous solution under mild conditions using sodium periodate to afford aldehyde‐capped poly(vinyl alcohol) chains. [44] Inspired by this well‐established chemistry, we recently decided to investigate the periodate oxidation of poly(glycerol monomethacrylate) (PGMA) to produce an aldehyde‐functional methacrylic polymer (Scheme 1; Supporting Information). However, periodate oxidation of a 10 % w/w aqueous solution of PGMA39 at 22 °C merely produced a macroscopic precipitate. This suggests that the target aldehyde‐functional methacrylic homopolymer (PAGMA) is actually hydrophobic. In principle, such precipitation could be the result of reaction between the cis‐diol and aldehyde units at intermediate conversion. However, reaction exotherms (data not shown) and visual inspection of the reaction mixtures suggest that the timescale required for the cis‐diol oxidation is much shorter than that for precipitation. Thus, it seems more likely that intermolecular crosslinking occurs between geminal diols and aldehydes (Supporting Information, Scheme S1).

Scheme 1.

Selective oxidation of a water‐soluble PGMA39 homopolymer precursor using a stoichiometric amount of sodium periodate in aqueous solution at 22 °C affords PAGMA39 as a water‐insoluble precipitate.

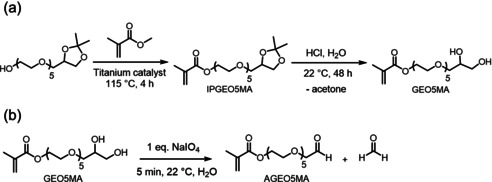

In view of these problems, we designed a new cis‐diol‐based methacrylic monomer (GEO5MA; Scheme 2 a). We envisaged that the pendent oligo(ethylene glycol) moiety in GEO5MA should confer sufficient hydrophilic character to ensure water solubility after converting its terminal cis‐diol group into an aldehyde via periodate oxidation to form either AGEO5MA monomer (Scheme 2 b) or the corresponding PAGEO5MA homopolymer.

Scheme 2.

a) Two‐step synthesis of GEO5MA monomer starting from an isopropylidene glycerol precursor as a hydroxy‐functional initiator. This precursor is then transesterified with methyl methacrylate to produce IPGEO5MA, before removing the ketal protecting group with acid to afford GEO5MA monomer. b) Oxidation of GEO5MA in aqueous solution using sodium periodate at 22 °C affords AGEO5MA with formaldehyde as a by‐product. The same selective oxidation can be used to convert PGEO5MA homopolymer into PAGEO5MA homopolymer using identical reaction conditions.

Results and Discussion

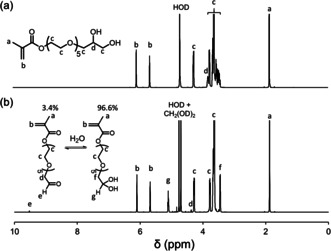

The two‐step synthesis of GEO5MA monomer was conducted on a 1.2 kg scale via 1) transesterification of isopropylideneglycerol penta(ethylene glycol) using methyl methacrylate to afford IPGEO5MA (Scheme 2 a) and 2) acid hydrolysis to remove the acetone protecting group (Supporting Information). The chemical structure of this new methacrylic monomer was confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy (Figure 1 a; Supporting Information, Figure S1a), mass spectrometry, elemental microanalysis and FT‐IR spectroscopy (Supporting Information). The integrated signals in the 1H NMR spectrum are consistent with the proposed monomer structure. Its 13C NMR spectrum contained ten distinct signals. A characteristic signal at ≈160 ppm was assigned to the ester carbonyl carbon; its relatively low intensity is attributed to the slow relaxation time for such quaternary carbon atoms. [45] The presence of a methacrylate group is confirmed by signals at 135 and 127 ppm. Several signals between 62.6 and 71.3 ppm are assigned to the pendent oligo(ethylene glycol) chain and include characteristic signals for the carbons attached to hydroxyl groups. According to mass spectrometry, the number of ethylene glycol units per oligo(ethylene glycol) group ranged from 2 to 7, with a mean value of 5.

Figure 1.

1H NMR spectra (D2O) recorded for a) GEO5MA monomer and b) AGEO5MA monomer (CH2(OD)2 denotes the hydrated form of formaldehyde).

Oxidation of a 10 % w/w aqueous solution of GEO5MA using a NaIO4/cis‐diol molar ratio of unity (Scheme 2 b) led to essentially complete oxidation of the terminal cis‐diol units within 5 min at 22 °C, as confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure 1). The structure of this new AGEO5MA monomer was confirmed by mass spectrometry, elemental microanalysis, 1H and 13C NMR (Figure 1 b; Figure S1b) and FT‐IR spectroscopy (Figure S3a). Two new signals appear at 9.52 and 5.09 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum for AGEO5MA, corresponding to an aldehyde group and a geminal diol, respectively. The aldehyde/geminal diol molar ratio was 0.034, which indicates that AGEO5MA exists primarily in its hydrated geminal diol form in D2O (Figure 1 b). Similar observations have been reported for other hydrophilic aldehydes in aqueous solution, such as acetaldehyde (Figure S2).[ 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ] During the periodate oxidation of GEO5MA to form AGEO5MA, the starting material can in principle react with the product to generate dimethacrylate species via (hemi)acetal chemistry. [1] In practice, the final product contains less than 1 % dimethacrylate impurity as estimated by 1H NMR spectroscopy. The 13C NMR spectrum also shows the appearance of two new signals at 169.5 and 88.0 ppm, which correspond to the aldehyde carbon and the geminal diol carbon, respectively. After purification by extraction with CH2Cl2, the RAFT aqueous solution polymerization of AGEO5MA was conducted using a dicarboxylic acid‐functionalized water‐soluble RAFT agent (CECPA) to target a mean degree of polymerization (DP) of 30 (Figure 2 a). More than 99 % conversion was achieved and the resulting PAGEO5MA30 was well‐defined, as indicated by its relatively narrow, unimodal GPC trace (M n=11 100 g mol−1; Đ=1.18; Figure 2 b). 1H NMR signals for the terminal aldehyde and geminal diol groups were detected for this homopolymer (aldehyde/geminal diol molar ratio=0.041).

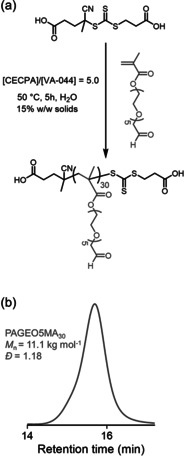

Figure 2.

a) Synthesis of PAGEO5MA30 via RAFT aqueous solution polymerization of AGEO5MA using a water‐soluble dicarboxylic acid‐functionalized RAFT agent (CECPA). b) DMF GPC trace for the resulting PAGEO5MA30 homopolymer (molecular weight data expressed relative to poly(methyl methacrylate) calibration standards).

Alternatively, RAFT aqueous solution polymerization of GEO5MA affords a near‐monodisperse PGEO5MA37 homopolymer (M n=17 200 g mol−1; Đ=1.18). When a NaIO4/cis‐diol molar ratio of unity was used to derivatize this precursor, essentially complete oxidation was achieved to afford PAGEO5MA37 homopolymer within 5 min at 22 °C (Table 1, Figure 3). The latter product proved to be water‐soluble at concentrations of up to 15 % w/w. In striking contrast, the product of the oxidation of PGMA39 homopolymer using a stoichiometric amount of periodate, denoted hereafter as PAGMA39, proved to be water‐insoluble when prepared at 1.5 to 10 % w/w (Supporting Information, Table S1). The much higher aqueous solubility observed for PAGEO5MA37 is attributed to the hydrophilic oligo(ethylene glycol) units on each repeat unit.

Table 1.

Extent of oxidation, DMF GPC molecular weight and dispersity data for the selective oxidation of PGEO5MA37 in aqueous solution at 22 °C using (sub‐)stoichiometric NaIO4/cis‐diol molar ratios ranging between 0 and 1.0.

|

NaIO4/cis‐diol molar ratio |

Extent of oxidation [%] |

M n [kg mol−1] |

Đ |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1.00 |

>99 |

16.5 |

1.22 |

|

0.75 |

78 |

15.9 |

1.24 |

|

0.50 |

49 |

16.8 |

1.21 |

|

0.10 |

11 |

17.4 |

1.22 |

|

0.00 |

0 |

17.2 |

1.18 |

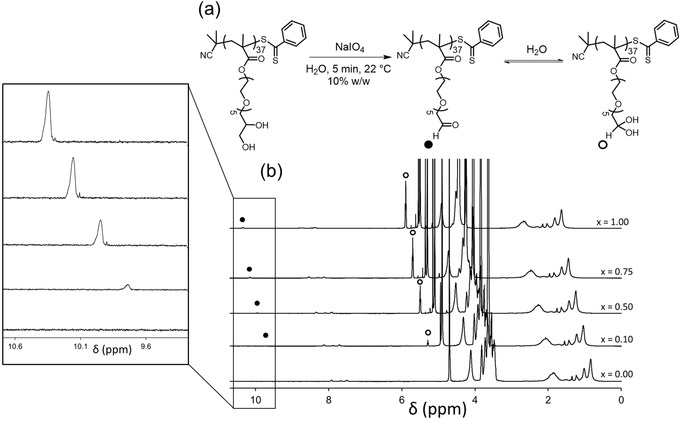

Figure 3.

a) Reaction scheme for the (partial) oxidation of a near‐monodisperse PGEO5MA37 precursor in aqueous solution using NaIO4 at 22 °C. Adjusting the NaIO4/cis‐diol molar ratio (x) between 0.1 and 1.0 generates a library of aldehyde‐functional water‐soluble statistical copolymers. b) Offset 1H NMR spectra (D2O) recorded for PGEO5MA37, P(GEO5MAn‐stat‐AGEO5MAm)37 (where m=0.11, 0.49 and 0.78), and PAGEO5MA37.

However, only a minor fraction of monomer repeat units may need to be converted into aldehyde groups for certain applications. Thus, partial oxidation of a PGEO5MA37 precursor using sub‐stoichiometric quantities of NaIO4 oxidant relative to its cis‐diol groups was also investigated (schematic in Figure 3 a).

Accordingly, utilizing NaIO4/cis‐diol molar ratios of 0.10, 0.50 or 0.75 produced a series of water‐soluble P(GEO5MAn‐stat‐AGEO5MAm)37 statistical copolymers with approximate degrees of aldehyde functionality of 0.11, 0.49 and 0.78 respectively, as estimated from 1H NMR spectroscopy studies (Table 1, Figure 3). Thus, the target degree of aldehyde functionality is always achieved (within experimental error). DMF GPC analyses confirmed that neither partial nor full oxidation of the PGEO5MA37 homopolymer had a significant effect on its molecular weight distribution (Table 1; Figure S4). Moreover, using a slight excess of NaIO4 relative to the pendent cis‐diol groups also resulted in partial loss of the dithiobenzoate end‐groups. Similarly, a PGEO5MA homopolymer (M n=124.1 kg mol−1, Đ=4.55) was synthesized via free‐radical polymerization in aqueous solution at 70 °C for 18 h. Selective oxidation of the cis‐diol groups on this homopolymer also had minimal effect on its (broad) molecular weight distribution (Figures S5 and S6).

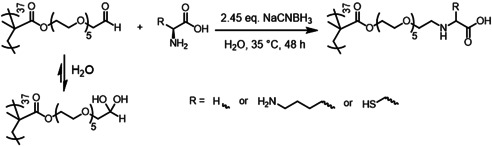

To investigate the scope of such new water‐soluble aldehyde‐functional polymers for conjugation with biologically‐relevant compounds, PAGEO5MA37 homopolymer was reacted in turn with three amino acids (glycine, lysine or cysteine; amino acid/aldehyde molar ratio=1.0) to form the corresponding Schiff base, followed by in situ reductive amination using excess NaCNBH3 (Scheme 3). These aqueous reaction mixtures were stirred at 35 °C for 48 h, with 1H NMR spectroscopy studies indicating very high extents of reaction (>99 %) in each case (Figure S7). Aqueous GPC analysis of the resulting water‐soluble polymers indicated that molecular weight distributions remained relatively narrow after this two‐step one‐pot derivatization (Figure S8).

Scheme 3.

Schiff base reaction of PAGEO5MA37 with an amino acid (e.g., glycine, lysine, or cysteine) followed by reductive amination using excess aqueous NaCNBH3 at 35 °C to afford a series of new zwitterionic homopolymers via a two‐step one‐pot wholly aqueous protocol.

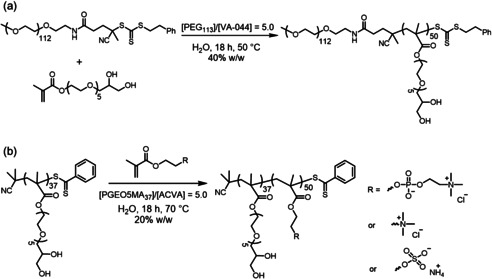

This protocol was then extended to water‐soluble diblock copolymers. A series of neutral, zwitterionic, cationic or anionic double‐hydrophilic diblock copolymers was prepared in which one of the blocks was PGEO5MA (Scheme 4). For the neutral diblock copolymer, a trithiocarbonate‐capped PEG113 precursor was simply chain‐extended via RAFT aqueous solution polymerization of GEO5MA at 50 °C. For the synthesis of the ionic diblock copolymers, a PGEO5MA37 precursor was chain‐extended via RAFT aqueous solution polymerization of 2‐(methacryloyloxy)ethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC), [2‐(methacryloyloxy)ethyl] trimethylammonium chloride (METAC) or ammonium 2‐sulfatoethyl methacrylate (SEM) at 70 °C. Each polymerization was allowed to proceed overnight to ensure high monomer conversion (≥98 % in all cases, as confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy; Table 2).

Scheme 4.

a) Reaction scheme for the synthesis of PEG113‐PGEO5MA50 via RAFT aqueous solution polymerization of GEO5MA at 40 % w/w solids using a PEG113/VA‐044 molar ratio of 5.0 at 50 °C. b) Reaction scheme for the synthesis of PGEO5MA37‐PX50 diblock copolymers (where X=MPC, METAC or SEM) at 20 % w/w solids using a PGEO5MA37/ACVA molar ratio of 5.0.

Table 2.

Summary of monomer conversions, extents of cis‐diol oxidation and GPC molecular weight data for a series of neutral, zwitterionic, cationic and anionic diblock copolymers (with reference homopolymers included for comparison).

|

GPC eluent |

Polymer composition |

Monomer conversion [%] |

Extent of cis‐diol oxidation [%] |

M n [kg mol−1][c] |

Đ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DMF |

PEG113 |

– |

– |

5.0 |

1.13 |

|

DMF |

PEG113‐PGEO5MA37 |

>99 |

– |

27.7 |

1.20 |

|

DMF |

PEG113‐PAGEO5MA37 |

– |

>99 |

26.2 |

1.22 |

|

Aqueous[a] |

PGEO5MA37 |

– |

– |

5.8 |

1.29 |

|

Aqueous[a] |

PGEO5MA37‐PMPC50 |

>99 |

– |

13.1 |

1.34 |

|

Aqueous[a] |

PAGEO5MA37‐PMPC50 |

– |

99 |

13.4 |

1.38 |

|

Aqueous[b] |

PGEO5MA37 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

Aqueous[b] |

PGEO5MA37‐PMETAC50 |

98 |

– |

23.4 |

1.12 |

|

Aqueous[b] |

PAGEO5MA37‐PMETAC50 |

– |

>99 |

23.3 |

1.11 |

|

Aqueous[a] |

PGEO5MA37 |

– |

– |

5.7 |

1.34 |

|

Aqueous[a] |

PGEO5MA37‐PSEM50 |

>99 |

– |

11.0 |

1.30 |

|

Aqueous[a] |

PAGEO5MA37‐PSEM50 |

– |

>99 |

12.7 |

1.36 |

[a] 0.2 M NaIO3, 0.05 M TRISMA buffer, pH 7. [b] 0.5 M acetic acid, 0.3 M NaH2PO4, pH 2. [c] Relative to PEG/PEO standards.

DMF GPC analysis indicated a high blocking efficiency for the RAFT solution polymerization of GEO5MA using the PEG113 macro‐CTA and the resulting PEG113‐PGEO5MA50 diblock copolymer had a relatively low dispersity (Đ=1.20; Table 2; Figure S9a). However, aqueous GPC analysis was required to assess the molecular weight distributions of the ionic diblock copolymers. (Table 2; Figures S9b–d). Oxidation of the pendent cis‐diol groups on the PGEO5MAx chains was investigated using a NaIO4/cis‐diol molar ratio of unity at a diblock copolymer concentration of 20 % w/w. According to 1H NMR analysis, the extent of derivatization was at least 99 % in all cases (Table 2). DMF GPC analysis confirmed that periodate oxidation had minimal effect on the molecular weight distribution (Đ=1.22; Figure S9a) in the case of the PEG113‐PGEO5MA50 diblock copolymer. Similar results were obtained for the zwitterionic, cationic and anionic diblock copolymers when using aqueous GPC (Table 2; Figures S9b–d).

Conclusion

In summary, we have reported the atom‐efficient synthesis of a new cis‐diol‐based methacrylic monomer (GEO5MA) that is readily converted into a hydrophilic aldehyde‐functional monomer (AGEO5MA) via selective oxidation using NaIO4 in aqueous solution. Unlike almost all other literature examples of aldehyde‐based vinyl monomers, this latter monomer is water‐soluble and can be polymerized with good control via RAFT aqueous solution polymerization. Alternatively, homopolymerization of the GEO5MA precursor under similar conditions affords a well‐defined water‐soluble PGEO5MA precursor that can be converted into PAGEO5MA under mild conditions using a stoichiometric amount of NaIO4 oxidant. On the other hand, using sub‐stoichiometric quantities of NaIO4 relative to the pendent cis‐diol units produces a range of water‐soluble aldehyde‐functional statistical copolymers. New PAGEO5MA‐based double‐hydrophilic diblock copolymers can be prepared and model Schiff base reactions have been conducted in aqueous solution under mild conditions using various amino acids to introduce zwitterionic groups. We anticipate that this new hydrophilic aldehydic vinyl monomer and its corresponding copolymers will offer a range of potential applications in the fields of cell biology and biomaterials.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

We thank EPSRC and GEO Specialty Chemicals for funding CDT PhD studentships for E.E.B. and C.P.J. (EP/L016281). GEO Specialty Chemicals (Hythe, UK) is acknowledged for permission to publish this work. Dr. K.I.A. Doudin is thanked for his help with acquisition of 13C NMR spectra for both PGEO5MA37 and PAGEO5MA37.

E. E. Brotherton, C. P. Jesson, N. J. Warren, M. J. Smallridge, S. P. Armes, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 12032.

References

- 1. Smith M. B., March J., March's Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure, Wiley, Hoboken, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Collins J., Wallis S. J., Simula A., Whittaker M. R., McIntosh M. P., Wilson P., Davis T. P., Haddleton D. M., Kempe K., Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2017, 38, 1600534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Collins J., Kempe K., Wilson P., Blindauer C. A., McIntosh M. P., Davis T. P., Whittaker M. R., Haddleton D. M., Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 2755–2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tao L., Mantovani G., Lecolley F., Haddleton D. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 13220–13221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scholz C., Iijima M., Nagasaki Y., Kataoka K., Macromolecules 1995, 28, 7295–7297. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nagasaki Y., Okada T., Scholz C., Iijima M., Kato M., Kataoka K., Macromolecules 1998, 31, 1473–1479. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iijima M., Nagasaki Y., Okada T., Kato M., Kataoka K., Macromolecules 1999, 32, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Otsuka H., Nagasaki Y., Kataoka K., Biomacromolecules 2000, 1, 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bilgic T., Klok H. A., Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 3657–3665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alconcel S. N. S. S., Kim S. H., Tao L., Maynard H. D., Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2013, 34, 983–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jackson A. W., Fulton D. A., Macromolecules 2012, 45, 2699–2708. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cao C., Yang K., Wu F., Wei X., Lu L., Cai Y., Macromolecules 2010, 43, 9511–9521. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Whitaker D. E., Mahon C. S., Fulton D. A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 956–959; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 990–993. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang J., Chen X., Qin H., Liang H., Lu J., Polymer 2019, 160, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rossi N. A. A., Zou Y., Scott M. D., Kizhakkedathu J. N., Macromolecules 2008, 41, 5272–5282. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heo G. S., Cho S., Wooley K. L., Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 3555–3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu Z., Liang H., Lu J., Macromolecules 2010, 43, 5699–5705. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xiao N. Y., Li A. L., Liang H., Lu J., Macromolecules 2008, 41, 2374–2380. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xiao N., Liang H., Lu J., Soft Matter 2011, 7, 10834–10840. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Murray B. S., Fulton D. A., Macromolecules 2011, 44, 7242–7252. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wiley R. H., Hobson P. H., J. Polym. Sci. 1950, 5, 483–486. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qiu L., Xu C. R., Zhong F., Hong C. Y., Pan C. Y., Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2016, 217, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xiao W.-D. B. N.-Y., Zhong L., Zhai W.-J., Xiao N. Y., Zhong L., Zhai W. J., Bai W. D., Acta Polym. Sin. 2012, 8, 818–824. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wechsler M. E., Dang H. K. H. J., Dahlhauser S. D., Simmonds S. P., Reuther J. F., Wyse J. M., Vandewalle A. N., Anslyn E. V., Peppas N. A., Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 6141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu M., Chen J., Huang W., Yan B., Peng Q., Liu J., Chen L., Zeng H., Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 2409–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sun G., Cheng C., Wooley K. L., Macromolecules 2007, 40, 793–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Foyer G., Barriol M., Negrell C., Caillol S., David G., Boutevin B., Prog. Org. Coat. 2015, 84, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sun G., Fang H., Cheng C., Lu P., Zang K., Walker A. V., Taylor J.-S. A., Wooley K. L., ACS Nano 2009, 3, 673–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wiley R. H., Hobson P. H., J. Polym. Sci. 1949, 4, 483–486. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Legros C., De Pauw-Gillet M. C., Tam K. C., Lecommandoux S., Taton D., Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 62, 322–330. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ishizone T., Hirao A., Nakahama S., Kakuchi T., Yokota K., Tsuda K., Macromolecules 1991, 24, 5230–5231. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hwang J., Li R. C., Maynard H. D., J. Controlled Release 2007, 122, 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yokoyama M., Miyauchi M., Yamada N., Okano T., Sakurai Y., Kataoka K., Inoue S., Cancer Res. 1990, 50, 1693–1700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pelegri-O'Day E. M., Matsumoto N. M., Tamshen K., Raftery E. D., Lau U. Y., Maynard H. D., Bioconjugate Chem. 2018, 29, 3739–3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Broyer R. M., Grover G. N., Maynard H. D., Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 2212–2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stukel J. M., Li R. C., Maynard H. D., Caplan M. R., Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Christman K. L., Maynard H. D., Langmuir 2005, 21, 8389–8393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Christman K. L., Requa M. V., Enriquez-Rios V. D., Ward S. C., Bradley K. A., Turner K. L., Maynard H. D., Langmuir 2006, 22, 7444–7450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Blankenburg J., Maciol K., Hahn C., Frey H., Macromolecules 2019, 52, 1785–1793. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mancini R. J., Lee J., Maynard H. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8474–8479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sawicki E., Hauser T. R., Stanley T. W., Elbert W., Anal. Chem. 1961, 33, 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Flory P. J., Leutner F. S., J. Polym. Sci. 1948, 3, 880–890. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Melville H. W., Sewell P. R., Makromol. Chem. 1959, 32, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Harris H. E., Pritchard J. G., J. Polym. Sci. Part A 1964, 2, 3673–3679. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Williams D. H., Fleming I., Spectroscopic Methods in Organic Chemistry, McGraw-Hill, Oakland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhao R., Lee A. K. Y., Soong R., Simpson A. J., Abbatt J. P. D., Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 5857–5872. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rivlin M., Eliav U., Navon G., J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 4479–4487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lewicki J. P., Fox C. A., Worsley M. A., Polymer 2015, 69, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wolfel A., Romero M. R., Alvarez Igarzabal C. I., Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 112, 389–399. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary