SUMMARY

Common warts (verrucae vulgares) are the most common complaint in routine dermatological practice. Warts can be painful on pressure and are often an aesthetic problem, but they are not a major threat to the person’s general health. Treatment options are symptomatic and do not eradicate the causative agent. Dermatological surgery procedures such as cryotherapy, electrocauterization and excochleation can be painful, with common recurrences. These are the most important reasons for revival of the treatment procedures and remedies based on traditional medicine. Traditional medicine is still commonly practiced as a form of self-healing. This paper presents the most commonly used wart remedies of plant, animal and mineral origin, along with various magic practices. We emphasize that this paper is written from the viewpoint of physicians, practitioners of dermatology, not as a study in the history or culture. The main objective of the study was to explore various substances and methods people use as home remedies for warts. We performed a case study survey among the general population by interviewing 147 adult participants using a simple preliminary questionnaire inquiring about preferred treatment and knowledge about common warts.

Key words: Warts; Dermatologic surgical procedures; Cryotherapy; Medicine, traditional; Surveys and questionnaires

Introduction

Warts are benign epithelial proliferations associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. They are a common skin condition that can range in severity from a minor nuisance that resolves itself spontaneously to a chronic condition. Warts are transmitted by direct contact and infect exclusively epithelial cells of the skin or mucous membranes. The four most common types of cutaneous warts are common vulgar warts, plantar warts, flat warts and genital warts. Although they are rarely a serious health problem, warts can cause physical impairment and psychosocial discomfort (1).

Treatment options differ according to the location, type and size of lesion. Commonly used treatments are cryotherapy and electrocauterization, but they can be painful and leave scars, and they also have high failure and recrudescence rates. Other methods include surgery with curettage, laser ablation with CO2 or dye lasers, keratolytic agents such as salicylic acid, acetic acid, tretinoin or 20%-50% trichloroacetic acid, cytostatics such as 1% podophyllotoxin or 5-fluorouracil, and immune-response modifiers such as imiquimod and Polyphenon E as a commercial extract of green tea leaves (2). Topical use of acetic acid solutions is one of the treatments for HPV infections, but over-the-counter availability of acetic acid solutions for medical use presents a potential hazard for misuse (1).

Different explanations for warts and different treatments that used plants, animal secretions, precious stones, metals, minerals and ores, air, earth, water, fire, heat and warmth, moonlight, sunlight, positions and movements of celestial bodies, prayers, blessings, curses, magical incantations and practices, human secretions, human nature – sympathy, antipathy, power of thought, one’s own or another person’s suggestion, rest and movement, and sleeping and dreaming were devised throughout human history (3).

In the past, people resorted to traditional remedies mainly because professional medical care was inaccessible or expensive. In the modern western world, traditional remedies are gaining popularity because they are believed to be more natural and healthier (4). In the past, traditional medicine was practiced by herbalists, healers, priests, nuns, midwives, mystics, or generally people with a knack for it (5). The application of alternative healing methods such as acupuncture, homeopathy and chiropractics varies vastly from country to country. Since healers practicing these methods have received formal education, these treatment methods do not fall under the category of traditional medicine (unlike self-healing homeopathic remedies, acupressure, or massage) (6). A series of historical folk medicine books called Ljekaruše offers a wealth of advice on the treatment of warts. Ljekaruše were typically written by friars who did not have academic medical education. These were in fact collections of recipes and advice about the healing of human and animal illnesses in the areas where the friars served. They contained advice on hygiene, diet, and phytotherapy, but also magical procedures that were widely practiced in the period when these books were written. Many of the ljekaruše that have been preserved date back to the 17th and 18th centuries, but they continued to be written in the 19th and even in the first half of the 20th century. Ljekaruše from this period are most numerous because they were typically owned by families as healing handbooks and often changed hands or were copied, with new information added, which was one of the way of sharing folk experiences (7).

In Ljekaruša by Friar Dobroslav Božić from 1878, the following wart treatment advice is offered: “1) take the spider that crawls on your wall, crush it while it still lives, and apply it to the area infected by warts, or put it on a rag and cover the infected area, the warts will go away; 2) crush a sheep dropping, cook it with some honey, and apply; 3) crush the greater celandine plant and apply the juice to the wart; 4) crush the stonecrop plant, mix its juice with salt and apply it to the wart; 5) take the liver of a he-goat and apply it to the wart while hot; 6) when a horse drinks water and rinses its mouth with it, wash your hands in this water; 6) when a warbler flies over, rub your warts quickly, but do not tell a soul” (8).

It is interesting to note that older publications differentiate genital warts and warts on other parts of the body. Warts located in the genital area were thought to be related to other sexually transmitted diseases, and were considered to be the result of increased pus discharge. It is understandable, since the existence of viruses was not scientifically proven yet, and the folk culture believed most diseases to have immaterial and mystical origins (9).

The goal of this study was to collect information about natural methods of treating warts in traditional medicine. If we draw a parallel between Ljekaruše in the 19th century and other publications onward and discussion boards today, we can safely assume that most of the advice and methods recommended online that claim to be of natural and folk origin are a variation of the ones found in old literature and oral tradition.

This paper aims to inform physicians about the increasingly relevant details of traditional medicine used in treating warts such as benefits, potential risk, side effects and adverse effects it could have on certain population groups.

Materials and Methods

This research represented an intersection between dermatological research and research of the history of medical practices. This paper does not aim to prove effectiveness of certain products, ingredients, remedies or treatment procedures nor does it aim to demonstrate the potential differences in results concerning the participant sex, age, ethnicity, education level or occupation. Our goal when writing this paper was to prove what products, ingredients, remedies or treatment procedures had been used and to offer a scientific background of such practices, so conducting a statistical analysis was redundant.

Information was collected from a number of written sources that portray alternative traditional medicine, from as early as late 19th century to this date. The books and publications were obtained from old family libraries, museums and archives.

In order to get more reliable results, along with research of the literature we conducted a survey among the general population, thus bypassing the doctor-patient relationship. As literature writes about treatment options in the form of advice, a population survey was needed to add more honest and authentic information about the type of treatment that was actually used. This survey included 147 participants who were adults recruited on the block, at community centers, various cultural and art societies and pensioner societies. The participants were screened using a simple preliminary question inquiring if the participants had at any points experienced warts or corns. If they answered yes, they were asked to complete the questionnaire.

We asked the participants to answer the following questions: 1) When you were affected by warts, did you (a) seek medical help, (b) try to treat the warts on your own, or (c) both? 2) If you tried to treat warts on your own, did you use (a) over-the-counter products purchased at a pharmacy, (b) homemade, folk remedies, or (c) both? 3) Specify the name of the product you used or the basic ingredient of the home remedy you used, or describe the treatment procedure; and 4) Have you, at any point during your treatment, recited any sort of an incantation, prayer or ‘spell’? If so, please write down the exact formulation or the basic words that it contained.

Results

In our survey, we collected results from 147 respondents from the general population. The participants were screened using a simple preliminary question inquiring if the participants had at any point experienced warts and if the answer was positive, they were asked to complete the questionnaire. When asked about the action they had taken when affected by warts, 42 (29%) participants answered that they had tried to treat the wart themselves, 34 (23%) participants said that they had sought medical help, and 81 (55%) answered that they had done both. When questioned about the type of self-administered treatment of warts they had used, 59 (40%) respondents answered that they had used a product purchased at a pharmacy, 38 (26%) said they had used homemade, folk remedies, and 81 (55%) answered that they had used both. In the third question, we asked the participants to specify the name of the product they had used, name the basic ingredient of the home remedy, or describe the treatment procedure. We collected all answers obtained from survey participants. Some of them used just one product or remedy, and others used several, in different combinations. Seven of the questionnaires had to be dismissed due to illegible answers (Table 1).

Table 1. Home remedies and treatment procedures used by participants to cure warts.

| Type of home remedy or treatment | Number of participants having used it |

|---|---|

| Greater celandine tincture | 44 |

| Callus and wart drops (active ingredients collodium, salicylic acid, etc.) | 33 |

| Tried to cut the wart off with scissors, nail clipper or similar sharp tools | 27 |

| Cryotherapy spray | 21 |

| Fig tree sap | 17 |

| Greater celandine extract | 15 |

| Bee glue (propolis) | 9 |

| Garlic | 7 |

| Tied a thread | 5 |

| Burned the wart with a heated needle or cigarette | 5 |

| Chalk | 4 |

| Houseleek | 3 |

| Concentrated acetic acid | 2 |

| Urine | 1 |

| Saliva | 1 |

Lastly, we asked the participants whether they had, at any point during the treatment, recited any sort of an incantation, prayer or ‘spell’, and if affirmative, to write down the exact formulation or the basic words that it had contained. Only five participants provided affirmative answer to the fourth question.

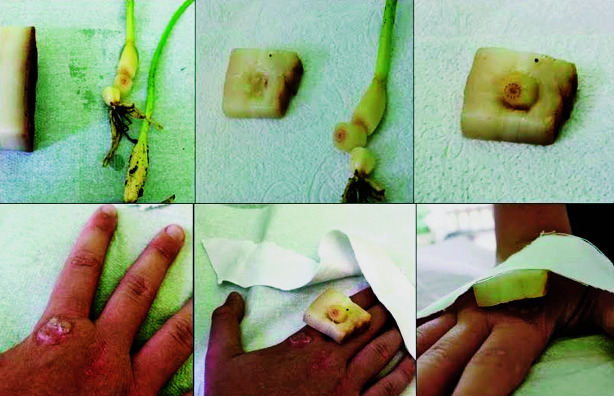

We identified some interesting common wart treatments reported by two elderly participants aged 92 and 85. They would make a hole in the white part of bacon (the fat) and insert a piece of root from a meadow saffron (Colchicum autumnale) bulb in it, along with a piece of wild garlic (Allium ursinum) or common garlic (Allium sativum). They would then attach this to the wart using a piece of linen or cotton cloth and repeat the process every other day until the wart turned dark, which was a sign that it was destroyed (necrosis) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Use of ‘sandwich technique’: wild garlic root is inserted into a hole inside a piece of bacon and attached to the wart using a linen cloth.

Discussion

Many scientific studies have been published about virustatic and virucidal properties of herbal remedies, but we must stress that scientific experiments differ considerably from typical traditional medicine and self-healing procedures. A scientific experiment utilizes standardized preparations, mainly concentrated or fractionated active ingredients, whereas traditional medicine employs herbal juices made by crushing plants and preparing them as simple tinctures (macerates prepared in available alcoholic solutions, fruit brandies, wine, and vinegar, or infusions) (10). Homeopathic remedies such as Thuya occidentalis are popular alternative treatments (11).

Pharmacies offer a range of over-the-counter standardized greater celandine tinctures, callus and wart drops containing salicylic acid, propolis solutions, and cryotherapy sprays. All of these products are meant to be used topically. Most of the available products act as keratolytics, destroying the wart by using physical, chemical and mechanical agents. Patients could react to the necrosis stage, which precedes demarcation, with fear and concern that they might have made an error in the procedure. This fear and concern is most common in patients who used more concentrated acids or thermal procedures to treat their warts. Medical procedures such as cryotherapy, electrocauterization, and excochleation regularly cause blisters, wounds and damage to the tissue surrounding the wart (12).

The greater celandine or tetterwort (Chelidonium majus) is the plant most frequently used as a wart home remedy. Its latex is orange in color and contains chelerythrine and other alkaloids with antimitotic properties, as well as proteolytic enzymes that break down proteins (13). The common fig (Ficus carica) has a milky sap that exhibits the same keratolytic effects as salicylic acid (14). Garlic (Allium sativum) is a very popular remedy for a number of conditions in folk medicine, and many of its healing properties have been scientifically proven. Its sulfur-containing amino acids (glutamyl peptides, cysteine sulfoxide) have an immunomodulatory effect (15).

The existence of numerous scientific and traditional medicine treatment options shows that there is no universally successful cure for warts. On their own, warts are not a threat to a person’s general health, although they can occasionally cause localized pain, and rarely bacterial superinfection.

In our study, the subjects included taught us that they tended to be very critical when evaluating the effectiveness of a treatment. When a home remedy or treatment method works, they often quote scientific or pseudo-scientific proof that they found online, and when a remedy or treatment fails, they dismiss it as ‘an old wives’ tale’. For example, some participants considered the greater celandine tincture a treatment the effectiveness of which had been proven and that was always effective, whereas others whose treatment with this tincture had failed considered it a useless product.

The magical procedures that we encounter in literary and historical sources are mostly linked to the historical way of life in rural communities, and some of them would not be feasible nowadays. The most popular wart removal incantations are therefore related to the phases of the Moon. Most magic formulas begin and end with Christian invocations, which secure God’s blessings and permission to carry out these procedures, while distancing themselves from forbidden black magic. Magic rituals change, but the basic human tendency to believe in the paranormal persists (16).

Conclusion

Wart treatment is still very challenging in modern dermatology while there is no fully satisfactory course of treatment yet that would guarantee complete recovery, with no relapses. The treatment is not focused on eradicating the causative viral agent and most treatment options include multiple, painful procedures. This is the main reason why traditional medicine remedies and procedures are still used. The role of a physician in the healing process is undergoing reexamination. Any medical practice should be based on a partnership between the physician and the patient, in which decisions are made together, and responsibility is shared. Every person has the right to choose among different treatment options. The patient’s faith in medicine and in its commitment to the patient’s well-being is crucial in the choice of treatment. It is therefore very important to offer patients advice on the possible negative side effects, for instance, to warn them that concentrated acids and alkalis used in wart treatment can significantly damage the surrounding tissue.

It is very difficult to provide empirical evidence for the success of traditional remedies for warts and HPV infections manifested as skin lesions. Sophisticated and expensive virologic research is required. Modern research is more geared towards HPV strains that cause genital warts and have a higher malignant potential. That research has produced some very expensive drugs that are impossible to use routinely in the treatment of very common non-genital warts.

Good communication between patients and their physicians and sharing of information is mutually beneficial, and enriches the healing experience regardless of the source.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all survey participants for their contribution and to the Library of the Museum of Slavonia for giving us access to old books and rare publications.

References

- 1.Bellew SG, Quartarolo N, Janniger CK. Childhood warts: an update. Cutis. 2004;73:379–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgdorf WHC, Plewig G, Wolff HH, et al. Braun-Falco’s Dermatology. 3rd edn. Heidelberg: Springer Medizin Verlag; 2009:64-72. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Springer J. Liječnica u kući. 1st edn. Zagreb: Dresdenska nakladna knjižara M.O.GROH, Dresden-Zagreb; 1926. (in Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bukovčan T. “Želim odabrati koga ću voljeti i kamo ići na liječenje” – aktivizam u istraživanju komplementarne i alternativne medicine u Hrvatskoj. Etnološka istraživanja/Ethnological Researches. 2008;5(1):63-76, 85. (in Croatian)

- 5.Brenko A. Praktičari narodne medicine. Sociol Prost. 2009. March 23;42:309–38. [in Croatian] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher P, Ward A. Complementary medicine in Europe. BMJ. 1994;309:107–11. 10.1136/bmj.309.6947.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kujundžić N, Škrobonja A, Tomić T. Plehanska ljekaruša Zbirka lijekova sa zbirkom ljekovitih trava i uputom za pravit meleme i murćefe. Acta Med Hist Adriat. 2006;4(1):37–70. [in Croatian] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bukovčan T. Medicina u kandžama etnologije: mala regionalna povijest transformacije tradicijske medicine u medicinsku antropologiju. Stud Ethnol Croat. 2010;22(1):215–35. [in Croatian] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dohranović S, Bosnić T, Osmanović S. Značaj i uloga alternativne medicine u liječenju. Hrana Zdr Boles. 2012. September 30;1(2):39–47. [in Croatian] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toplak Galle K. Domaće ljekovito bilje. Zagreb: Mozaik knjiga; 2005. (in Croatian)

- 11.Joseph R, Pulimood SA, Abraham P, et al. Successful treatment of verruca vulgaris with Thuja occidentalis in a renal allograft recipient. Indian J Nephrol. 2013. September 23; (5):362–4. 10.4103/0971-4065.116316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saha S, Hossain DMS, Mukherjee S, et al. Calcarea carbonica induces apoptosis in cancer cells in p53-dependent manner via an immuno-modulatory circuit. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:230. 10.1186/1472-6882-13-230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kéry A, Horváth J, Nász I, et al. Antiviral alkaloid in Chelidonium majus L. Acta Pharm Hung. 1987;57(1-2):19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemmatzadeh F, Fatemi A, Amini F. Therapeutic effects of fig tree latex on bovine papillomatosis. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2003;50(10):473–6. 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2003.00702.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sultan MT, Buttxs MS, Qayyum MMN, Suleria HAR. Immunity: plants as effective mediators. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2014;54(10):1298–308. 10.1080/10408398.2011.633249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Randić M. Narodna medicina: liječenje magijskim postup-cima. Sociol Prost. 2009 Apr 14;41:67, 87-85, 105. (in Croatian)